Addicted to Losing

Athena

Other languages: Deutsch, Türkçe

To restart the revolution is not to rebegin it, it is to cease to see the world alienated, men to be saved or helped, or even to be served, it is to abandon the masculine position, to listen to femininity, stupidity, and madness without regarding them as evils. —J.F. Lyotard

Can you be immortalized without your life being expired? —Kendrick Lamar

In the summer of 2020, we saw the largest uprising in America’s history. Its racial character was undeniable: in a landscape of unfrozen civil war, the negro question once again took center stage. Among those most eager for destruction was the black working class, which made short work of police cars, cops, and storefronts. Looking back on these events, part of the reason the uprising died down was that it hit upon both technical and social limits. As has been pointed out by others, the “memetic” quality of the movement — i.e., the way it ramped itself up through the iteration of destructive gestures — reached its limit with the burning of the Third Precinct in Minneapolis, an attack that, while awe-inspiring, set a high bar to clear. On the other hand, in terms of its social limits, the imaginary of the rebellion, its revolutionary potentials, were shamelessly repressed by the Black counter-insurgency. The Black counter-insurgency consists of a network of middle class black folks, black academics, rich niggas and their cohorts who, in cooperation with the police, helped to put down the wave of property destruction by recuperating its energy towards the construction of a social movement. Managers are endemic to such movements, a role that the black counter-insurgency was all too eager to assume. In their hands, questions of revolution and how to make one evaporate into liberal talk of “abolition,” a slick cover for more police reform. Since this distinct brand of repression within movements is not isolated to 2020, but saturates both our past and present, it is decisive that we grasp its meaning and purpose.

In what follows, we wish to clarify the ground upon which the standpoint of Black counter-insurgency rests, the set of beliefs and assumptions that allow it to reproduce itself. Why is the notion that racialized people need masters so easily swallowed, even by so-called radicals? How do we injure the stupidity that is spread by this idea, this ongoing perception of people of color as unsuited to the task of ending the world? In today’s movements and organizing spaces, the reign of white supremacy is nourished by the paternal concern for the welfare of people of color, an insidious apparatus that works to attenuate our militancy by instilling in us feelings of inferiority and dependency. Our task therefore is twofold: not only must we confront racist repression at the hands of police in our streets, but also the fluid web of social control that extends beyond that terrain into our own social and political circles. In seeking answers to these questions, our aim is to make way for more unruly and ungrateful black and brown insurgents, a specter feared by both whites and non-whites alike.

Gimme danger, not safety

The politics of the black counter-insurgency is what Jackie Wang has called a “politics of safety.” For Wang, the politics of safety is based on the racializing requirement that, unlike their white counterparts, in order to warrant political consideration, oppressed people of color must be innocent. As she shows, the difference in treatment between the case of Trayvon Martin, a Black teen the regarded by the public as “a kid like any other,” and that of Isaiah Simmons, who was choked to death by multiple counselors in a juvenile facility, can be attributed to the former’s appearance of innocence. Trayvon sees ample news coverage and protests, while Isaiah’s criminal status exempts him from public empathy, relegating him to obscurity. This prerequisite of innocence serves a hidden assimilating function: empathy with the oppressed is possible precisely in proportion to how relatable they are to the public. Those who are racialized must appear as morally pure, or not at all. To have one’s oppression verified or authenticated, one is obligated to be innocent, in the way a child supposedly is — and therefore inferior, in the same way the child is thought to be. The politics of safety is a whitewashing operation. The boundaries of whiteness — what it permits and what it forbids — are established by reference to this distorted view of the dominated.

This infantilizing construction of the marginalized is used to justify a politics in which violent and conflictual ways of being are disqualified in the name of “keeping the less privileged safe.” When they police a demo that is beginning to get out of hand, those professing a politics of safety can then claim that they are doing so in the name of protecting the vulnerable in their flock. This is easier than confronting their real fear, namely, that non-white people and other marginalized groups might truly slip out of anyone’s control. In the case of people of color, the common articulation of struggle against white supremacy is one entirely without teeth. The savage, the negro, the person of color can only be thought of as fragile, to the point of ineptness. Confused non-whites believe it to be the duty of “radicals” to convince other non-whites to relate to themselves as if they lacked the kind of political agency that only white people can hold. Wang expresses this point succinctly:

People of color who use privilege theory to argue that white people have the privilege to engage in risky actions while POC cannot because they are the most vulnerable (most likely to be targeted by the police, not have the resources to get out of jail, etc.) make a correct assessment of power differentials between white and non-white political actors, but ultimately erase POC from the history of militant struggle by falsely associating militancy with whiteness and privilege. When an analysis of privilege is turned into a political program that asserts that the most vulnerable should not take risks, the only politically correct politics becomes a politics of reformism and retreat.

Today, calls for “white bodies to the front” are met not with ridicule but unflinching obedience. Even in anarchist circles, which one foolishly hopes would be immunized from such behavior, comrades fall victim to it. For instance, why do people of color so often find themselves exempted from the practices of folk justice applied to everyone else in radical milieus, prompting jokes about people of color being “uncancellable”? Why is it that, after all these years, it has been so hard for radicals to shake the politics of safety?

Wang wrote “Against Innocence” in 2012, but it feels as if it could’ve been written yesterday. Feeble attempts have been made to combat it, usually in the form of a lukewarm critique of vulgar identity politics, but these attempts are neither satisfactory nor novel. Is it enough to blame the issue on the Combahee River Collective’s concept of identity politics, which sought to clarify interlocking modes of oppression? Such critiques are all too eager to dismiss race and gender as central modes by which governmental power operates. These forms of power cannot simply be avoided, but must be moved through in order to be overcome. An indifference to the question of race only preserves one's sense of comfort, whether it be through self-serving emphasis on supposedly common elements of domination like class or through the naked denial of social difference. Moving through these structures requires that we confront what Idris Robinson calls the “morbid libidinal core of white supremacy, identity politics, intersectionality, and social privilege discourse.” For us, this means giving form to a sentimental analysis, one inseparable from an actual practice of civil war. By sentimental, I mean that we root through the innards of that space improperly marked as “personal,” going beneath the veneer of intellectual pretension to confront what hurts, frightens, and disorients us. The politics of safety, I propose, has flourished by preying upon the moral values dominant among radicals. An examination of such values then, may aid in plotting an escape route.

The politics of sacrifice

Where do our concepts of good, bad, and evil come from? In his landmark history of morality, the Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche illustrates the difference between two types of morality by recourse to a myth. Once upon a time, there were “masters” who were strong, and affirmed their strength and vitality as “good.” The concept of “bad” was an afterthought, associated only secondarily with traits proper to “slaves” who they considered beneath them. This set of values Nietzsche calls “master morality.” The slaves, oppressed by the masters, respond by transforming the meaning of good and bad, calling the strength of their masters evil, and (by extension) their own weakness good. According to Nietzsche, this reversal was a way of exacting a moral or spiritual revenge on the masters, since they lack the material strength to overthrow them. This cunning maneuver succeeded, at least for a time. However, Nietzsche argues that this tactic has overstayed its welcome, leaving in its wake a reigning slave morality that valorizes dispossession and weakness. Slave morality recognizes the good only where there is bondage, while regarding all attempts to escape from this bondage as evil. Nietzsche's prime example of slave morality is Christianity, which he sees as a denial of life and its pleasures, which holds the material world in contempt.

Nietzsche’s analysis of slave morality is useful. Even among anarchists/anti-state radicals, slave morality survives in the form of a politics of safety, an illness similar to Christianity. This should not be surprising, considering radical politics and Christianity have long had a love affair. As communist philosopher Walter Benjamin noted, many radical concepts are, after all, secularized theological concepts. To observe that the ruling moral values among radicals exhibit the traits of a slave morality need not amount to an endorsement of master morality. Slave morality doesn’t always arrive in the stiff posture of the priest. In the radical milieus it can also assume the disarming language of zines and hair dye, which only makes it all the more difficult to pin down. This new look of slave morality, which allows for the continued worship of weakness, is based on an illusion among radicals that they have already conquered asceticism. We laugh at the Christians and socialists, ignoring the beam in our own eye. If the politics of safety is an effective strategy of counter-insurgency, this is because it exploits the underlying slave morality of radicalism.

According to the slavish values of radicals, experiences of oppression — racial and otherwise — are assigned the quality of “goodness.” In other words, a diminished capacity for action is treated as a virtue in and of itself. Those vital, rebellious fragments that exist among the oppressed are swept aside in favor of a moral fetishization of wretchedness. This fetishization is reflected plainly in the ragged dress code of the radical circles, a cultural signification of one’s aversion to decadence. More generally, efforts of radicals to increase their power of acting, whether through acquiring spaces like houses and social centers, money for bail funds and projects, or even forming larger strategies about how to defeat the police in the streets are treated as a violation of an implicit set of values that venerates the experience of being trapped. These tactics are seen by some radicals as a dangerous ploy for power, which risk being reigned back into domination.

Skepticism surrounding what it means to build consistency as a revolutionary force is important, and we should be cautious about the recuperation of projects designed to give us more material power. But when the concern clearly bubbles up from a sensation that such tactics betray the holy, servile image of the revolutionary as someone with barely enough will to throw a brick, our sympathy should cease. To struggle against one’s subjugation is too often framed as a simple shift from the position of the slave to that of the master, every other path being met with disdain. The romanticization of revolutionaries as “beautiful losers” only ensures that the medicine goes down smoother. Such myths beg for disenchantment in reality, like Christianity before it, radicalist slave morality is ultimately premised on a rejection of life.

Like the megachurch preacher who scolds the taste for revenge and filth of queerness, the radical experiences shame in the face of every expression of strength, seeing in it nothing but a conspicuous consumption of privilege. In the name of liberation, the radical paradoxically calls for a political modesty: are you really going out dressed like that? We are at a point where even declaring that we want to be stronger raises a certain kind of alarm. Why should it?

Revolutions take strength. Deactivating that which governs us takes strength. We should want that power and should shamelessly seek it, rather than smothering it beneath the specious garb of asceticism. This shame that blocks us is rooted in what Nietzsche calls ressentiment, an envy felt toward another whom we believe to be the sole cause of our lack of power. Ressentiment is what leads radicals to police attempts at freedom that lie outside of their preferred grammar of conflict, which they wrongly interpret as the reason the enemy keeps winning.

Shame in the face of power surfaces as the primary driving passion of would-be revolutionaries. Rather than dreaming of the excesses this world holds back, and spitting on the poverty of its justice, its love, its pleasure, and what it passes off as “sociality,” radical culture responds punitively with the stick of shame, a reactive passion. The real exploitation of the oppressed is treated as a pretense to deny any and all ecstasy to radicals. Shame seeps into our bodies, to the point where we learn to see ourselves as little else than instruments of domination, until our own self-destruction becomes a moral duty. In this way, the suicidal despair that this world proliferates is thereby transmuted into a radical consciousness. The miserable and dejected preach their “good news”: the true revolutionary is unworthy of life. Living is for someone else, not for them. Nowhere is this groveling attitude more apparent than in that Maoist slogan, “serve the people.”

So much for the radlibs and protest managers. But what of the militants in our movements? With them, slave morality emerges as a politics of sacrifice. Their neglect of the question, “how are we to live?”, leads them to reproduce the same nightmare over and over. Whereas the liberal politics of safety embodies the condescension of Christian charity, the more “anarchistic” politics of sacrifice draws instead upon the legacy of Christian martyrdom. Rather than a playful mode of affirmation, its style is that of pleasureless service. The politics of sacrifice is ruthlessly utilitarian, but like all utilitarianism, its understanding of the good is completely detached from the world it actually inhabits. The tendency towards martyrdom among the advocates of violent direct action attests less to revolutionary piety than to a complete exhaustion of the imagination, a death drive thriving in an absent sense of the possible. Fighting against this world is reduced to the gesture of giving one’s life over to a complete destruction. Political effectiveness is measured by the degree of suffering one endures in their efforts at resistance. This sickening resignation to oblivion lives as much in the sad militant who prays to be arrested in the black bloc as it does in the anarchist organizer who stretches themselves thin to the point of breaking, because others have it worse. Outside of these attempts to chip away at Empire through sharp masochistic bursts, we live our lives otherwise unchanged. At bottom, the politics of sacrifice doesn’t really desire autonomy; such acts reflect instead a need to gratify that voice inside of us that tells us we don’t deserve any other world than this.

By giving our souls over to a flattened image of the oppressed, we fail to earn our own trust. In our reflection of the long, disastrous history of counterrevolution, we deny ourselves permission to attempt once more to transform our lives, reverting instead to a political sterility that excuses itself from the task of transformation entirely — after all, is this not the safer option?

The politics of sacrifice confers a predictable shape upon our struggles. We see this in the refusal to engage with the mass intelligence of crowds, the suspicion of any openness to cross contamination. The militant embodies a knight-like position with respect to the crowd: rather positioning themselves within it, they act like a kind distant protector, ever anxious to ensure that the membrane between savior and saved is never breached. Either they make themselves so small as to avoid influencing anyone, or they assume a paternalistic vanguard posture that tries to safely, but separately, guide the little lambs. The impurity proper to all genuinely strategic thinking, which invites us to explore the contours of a situation rather than defer to an ideology or tribe, is denied in favor of a puritanical mode of critical thinking. Rather than being a tool to challenge one’s base assumptions, “critique” assumes the form of a neurotic scanning of oneself and others in search of some hidden authoritarian germ. Milieus devour themselves through the endless production of holographic enemies, allowing the resentful to cloud our sight with confused battles whose only purpose is to satiate a drive for “salvation”, a nakedly desperate need to be needed. All of which is simply a smokescreen for the actual conflicts: a widespread rape culture, racial segregation among revolutionaries, and the unutterable fear of our own freedom. Nietzsche spoke of the “anarchist dogs” that roamed Europe; today we can speak of hyenas.

By giving in to the nihilistic politics of sacrifice and its disgust with the sweetly overflowing quality of existence, we excuse ourselves from creating new ways to increase our power of acting. In my experience, it is the radicals who issue from more privileged positions in the world that are most readily trapped in the politics of sacrifice, using increasingly finer points of marginalization rhetoric to assert their essential goodness and moral authority. Who among us hasn’t been at the business end of the middle class or white comrade, who transforms their soul-wrenching guilt into everyone else’s punishment? While rebellious segments of “the meek” are busy figuring out how to live in spite of it all, others scheme only about how to die. Certainly, all kinds of passions can motivate beautiful acts of sabotage. But what must be challenged is this abnegation that asserts itself as the only mode in which we wage war. We are blocked from the full spectrum of what makes us disobey when, in reality, there is plenty of room for the self-negating agony to break bread with contagious shared joy. The devil lies in an art of distances.

Learned helplessness

Let’s return to the question of race. Radicals of color become central objects in this politics of sacrifice. We are things that represent the stakes, either directly or symbolically. A black person cannot just be herself. Her fungibility makes her interchangeable with the gangbanger, the prisoner, or the factory worker in the global south, even if her own social and economic conditions have nothing in common with them. When white radicals coddle people of color, it is often out of a misguided effort to place themselves in contact with the “most wretched.” The concrete person of color is always already a stand-in, devoid of any being. The white’s desperation to be a savior and to spread the dichotomy between savior and saved reflects an unspoken sense of superiority, a racist narcissism. If I don’t act, who will? Certainly not those poor folks. The politics of sacrifice discourages militants from taking responsibility for their desire to rebel, as if rebelling for one’s own sake, or for one’s own reasons, were merely a gratuitous pleasure. It is forbidden to acknowledge that smashing cop cars is fun. The erotic dimensions of rebellion, the euphoria that comes from breaking this world apart, must be conjured away. To avoid the bludgeon of shame, a scapegoat will be needed; to this end, the pitiful racial other offers a perfect alibi. In this way, flattened categories of whiteness and blackness are enlisted as aids in the disavowal of anarchic desire. When whiteness is constructed as all-powerful and non-whiteness as helpless, the basis is created for a politics that is only for, rather than with others. Anarchic desire must be kept on a leash, corralled by a duty to serve the good of the racial Other exclusively. Non-white radicals are not immune to this racist logic, which survives even when we break off into our own milieus, in sad spirals of competitive fragility. In one way or another, the black and brown person — but especially the black person — can never be seen on her own terms. The relation of savior/saved that is perpetuated by the politics of sacrifice demands that for every nigger an overseer must be found. The perceived need for the overseer manifests itself even in non-white separatist circles, where it appears either as a desire for “BIPOC leadership,” or else in the suggestion that one is taking orders from a fictitious racialized proletariat that is always conveniently somewhere else.

What unites all radical milieus today is their structural need for people of color to be unfree, or at the very least, to feign unfreedom. Wherever radical milieus bind themselves to people of color through the duty of self-sacrifice, the racist burial of non-white militancy becomes an essential cohering force. This danger can be partially averted through the autonomous self-organization of racialized people, which can negate this, since, by saving ourselves, we render attempts to “save us” wrongheaded. However, as can be observed in today’s radical BIPOC circles, this becomes pointless if the aim is not to become stronger. The dull commiseration afforded by these spaces is no substitute for attack. The politics of sacrifice would have us believe that black and brown revolution is not something we make with each other, among friends, but the pursuit of an abstract and reductive idea of the good to which we must submit our lives, to the point of death. It is hard to avoid the impression that the Black Liberation Army was swayed by a similar spirit, despite how inspiring its efforts to spread anarchy often were. Its failure to build a popular guerilla front against the United States was at least in part due to its tendency to separate the task of struggle from the task of living, a problem intertwined with its insular vanguardism. The challenge of today’s struggle for black and brown autonomy is therefore twofold: on the one hand, to stay militant, without detaching ourselves from the question of how to live; on the other, to combat the gluttonous appetite of whiteness for non-white inferiority — in other words, its dependency complex. It is through the attachment to living that we remain pliable like a young tree, capable of feeling the free lives that we are fighting for, instead of just deferring this gift to those who come after us.

If black counter-insurgency continues to capture us, this is because we have failed to make worlds that seduce. Why do people of color become merely activists, rather than insurgents? Confusion plays its part, to be sure. But it may more so be that we have failed to find each other, to link up and partake in an open conspiracy against the racial nightmare. Too much emphasis has been placed on the banal contemplation of past victories and defeats, at the expense of the pulsating reality that lies before us. Militants of color speak endlessly of the sixties; but how do we elaborate black liberation in the present age, now that the subject of our revolts is really no one at all? How long can one lean on the rapidly deteriorating New Afrikan hypothesis, or huff the fumes emitted by bored academics spinning poetics out of the fossilized intensities of dead guerillas?

The politics of sacrifice must be broken. In the end, there is no one left to serve, and no one worthy of service. To break with it requires that we unchain all that is living in blackness, indigeneity, and all other evasions of whiteness. This affirmation is threatened by those profiting off the lucrative spectacle of our demolished culture. Watch BIPOC content online, talk about how proud you are of your skin, while ignoring that this civilization has eaten your traditions alive. Become educated, stay informed, and sit like a good negro until white people fix everything; they have the power now, just wait your turn until you get yours. Representation is a putrid balm — anyone who permits themselves even the slightest sense of touch can feel that our madness, a black madness, cannot be projected onto any screen. What those screens want us to believe is clear: there is nothing living to affirm in not being white. In those rare moments with other people of color where my spirit moves, attaching to something older than me, I have felt the opposite. These experiences have emboldened me. The aggressive campaigns of the spectacle to re-present the lives of the racialized in total submission, the millions of dollars spent on BIPOC non-profits and pointless activism, testify to the dangerous potential that exists in the genuine refusal of whiteness.

A fanged, boundless blackness

Whiteness wins if we let it. Its victory means the spread of a colonial shame that blocks our ability to enjoy unmaking this world. The voices of our ancestors become more muted and we, children of “savages and cannibals”, resign ourselves to becoming radlib gurus of our own suffering. For racialized people, the politics of safety and the politics of sacrifice are merely tools of white supremacy. Stop saying that niggas cannot riot for their own sake, that they are either confused or misled by whites. We owe our dead more than submission. Let us have the courage to say this: if decolonization still has any meaning, it is found in the uncompromising, violent upheaval of this world. The mediocre poetry and papers of BIPOC academics are not decolonial violence, liberal workshops about resiliency or black trauma are not decolonial violence. The strange, criminal gestures that send the cops scattering and the cybernetics of the metropolis into a panic are decolonial violence. How we live in tandem with this sedition, caring and loving one another, is intimately bound up in that violence. This ferocity is a fruit I wish to eat while I’m alive. To speak of whiteness without understanding what is required to destroy it is to let the leviathan speak through you. Years ago, Fanon saw the writing on the walls: we either become more white (that “we” is the most royal I can deploy, as it includes white people), pulled by the assimilating gravity of the present regime, or we revel in our corruption by blackness. We can understand this process as traced through an elaboration of black insurgency, which is always more perverse than its white counterpart, since the end-times are always already bound up within it.

Despite it all, we still glimpse ways to escape the racial order and authority. Why not turn to our fugitivity, an irreducibly black mode of sociality which affirms blackness as a force that escapes control? Fugitivity is being with and for one another as we are on the run, dashing towards the Outside of the law, whiteness, and order. Its perversity is absolute, a porous conspiracy that is promiscuous with its blackness, refusing to check one at the door. Fugitivity says: when our play entails the destruction of the enemy world, then the more the merrier. Perhaps it can help us escape our addiction to defeat, and the chokehold it exerts over people of color and whites alike. Cutting through the despair spread by the politics of sacrifice, a fugitive blackness beckons us toward the exit door of the present. To have done with shame, with the idea that the practice of ending this world should be sad work, demands that we embrace a militancy that is joyful. We must not give in to our new overseers, even if they speak the tongue of the old radicals and have brown or black skin. Through affirming the life that escapes whiteness, we discover our strengths, an act which is loathed by that which governs. We embrace the excesses of our own rebellion, how we dance, hold on to each other, and don’t take any shit. We revel in our obscenity, our lucidity, the living memory of when the miserable settlers hadn’t yet enclosed the world. To live in the black is to evade the traps of politics, of representation, of diversity and inclusion. It is to improvise ties between fragments of marronage. We want everything. Nothing less.

March 2024

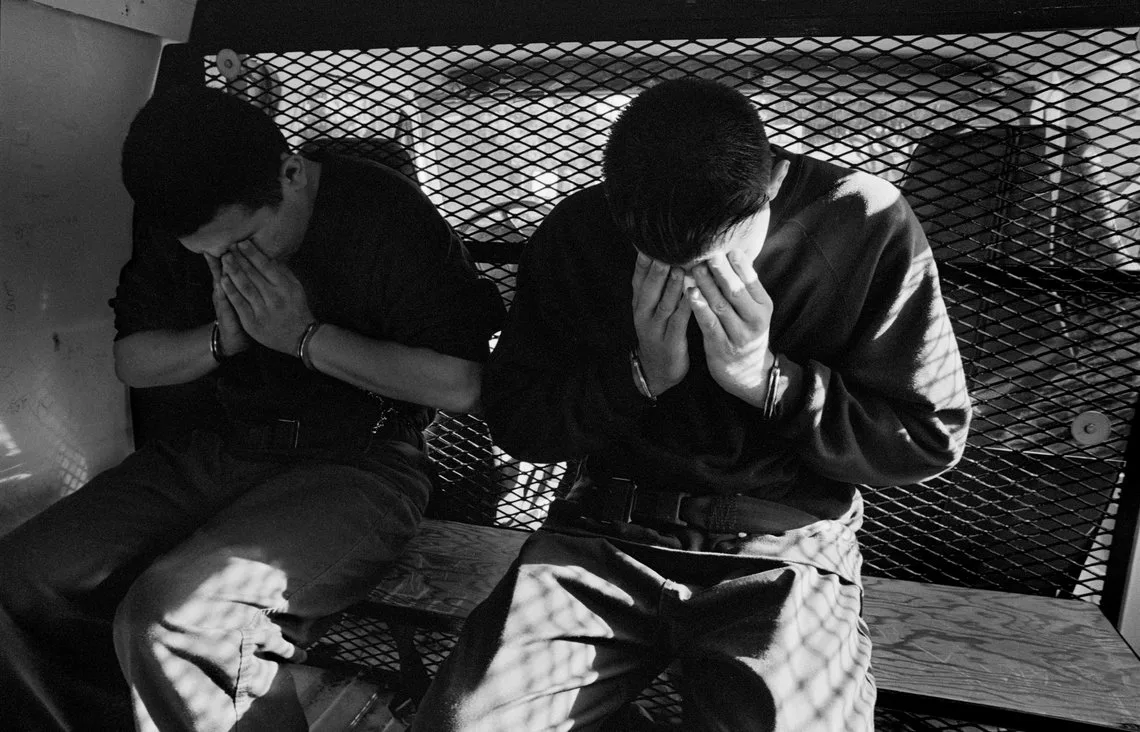

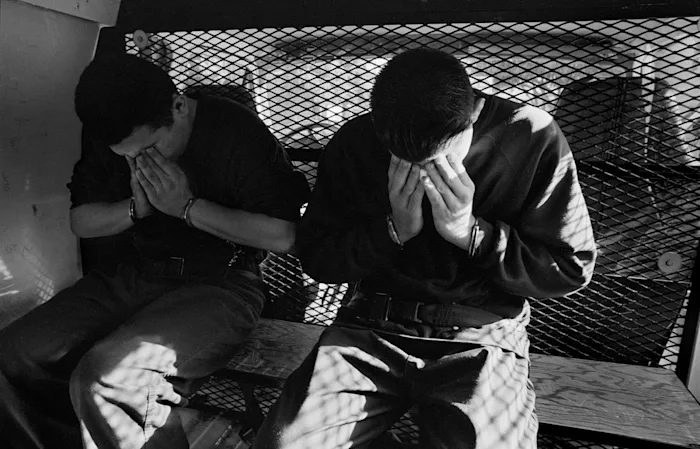

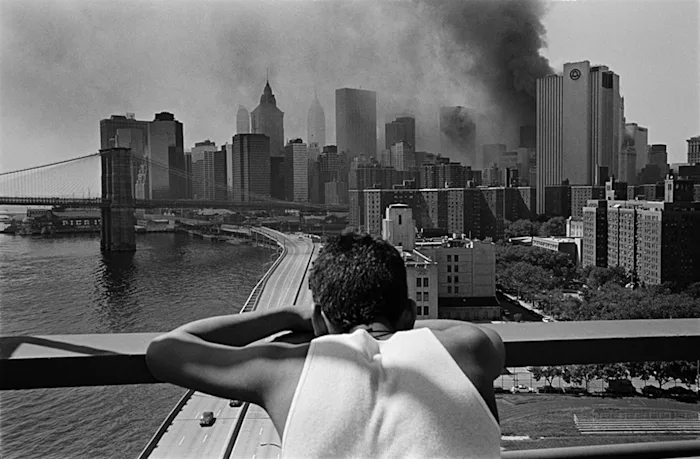

Images: Joseph Rodriguez