Against the Computer and Its World

The Destructionist International

As their new film Breached: A Chronicle of Cargo Theft begins to be screened, Andrew Culp and Thomas Dekeyser of the “Destructionist International” sat down with Ian Alan Paul to discuss their critique of technology and politics, their approach to contemporary documentary, and their embrace of practices of negativity.

Other languages: Français, Türkçe, Español, Ελληνικά

Ian Alan Paul: I wanted to begin our conversation with Machines in Flames (2022), your experimental film that grapples with the history of the French militant group CLODO, a collective that set technology firms alight in the early 1980s. The project articulates a critique of the internet as a global archive, one that serves the interests of cybernetics and policing, and which we learn in the film that your own research process becomes implicated in. At one point, the narrator reflects that searching for online traces of CLODO’s attacks risked reproducing the “detective-logic of the digital,” eventually asking: can an attack against an archive “ever be documented or represented without reiterating its logic?” Echoing this concern in the film, let me ask you: we now see militant revolts waged explicitly against the development and deployment of various digital technologies — many of which have been organized to some degree online and even end up circulating there as content as well — yet they have seemingly been unable to fully outrun or formally escape the informatic logic of the systems they struggle to dismantle. How does CLODO offer us another way of thinking about the history of the internet, and what it means to resist its archival and repressive function in capitalist society?

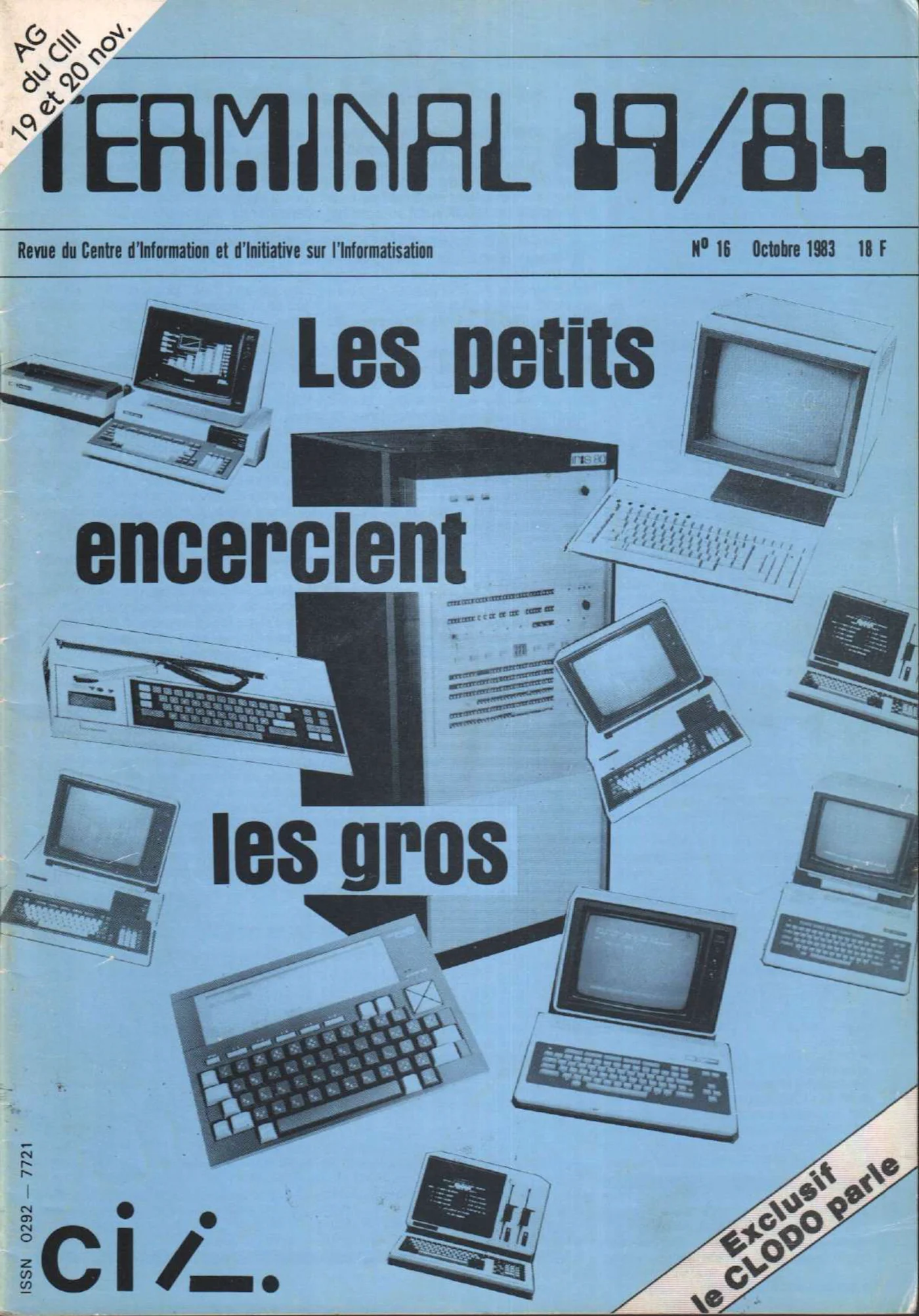

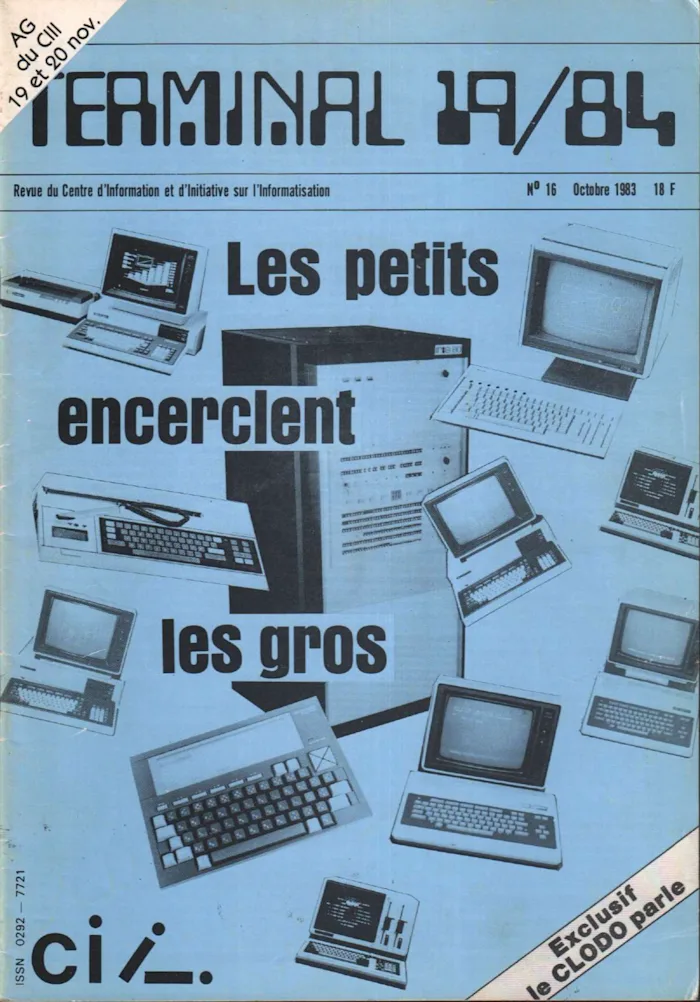

Andrew Culp: The lure of technology is strong. It sweetly promises to make life simultaneously easier and more powerful. CLODO emerged at a turning point: the microcomputer was just hitting the consumer market. Just look at the cover of the issue of the alternative magazine Terminal that first republished CLODO communiqués. The cover warned that “The Little Ones Are Taking Over the Big Ones” — cautioning that mainframes were quickly being displaced by desktop computers. And as we now know, even desktops would eventually be replaced by the nanocomputers small enough to be carried in pockets and embedded in the landscape through sensors, cameras, and “smart” devices. CLODO offers a refreshing alternative to the prevailing story that this transition was a Jetsons tale of convenience and empowerment: that technological visionaries developed increasingly useful devices that were eagerly adopted by a burgeoning consumer class eager to achieve a new life of luxury.

For a time, CLODO's criticism of technology was lumped in with that of the Luddites. There is certainly an affinity; but the Luddite’s criticism was a workerist push-back about the false promises of leisure. Like Marx would later write, capitalists introduce better-and-better technology to secure a short-term superprofit and to discipline labor — if anyone’s life is made easier, it is that of the manager who uses the word “efficiency” as a euphemism for expanding the number of workers they watch over and command.

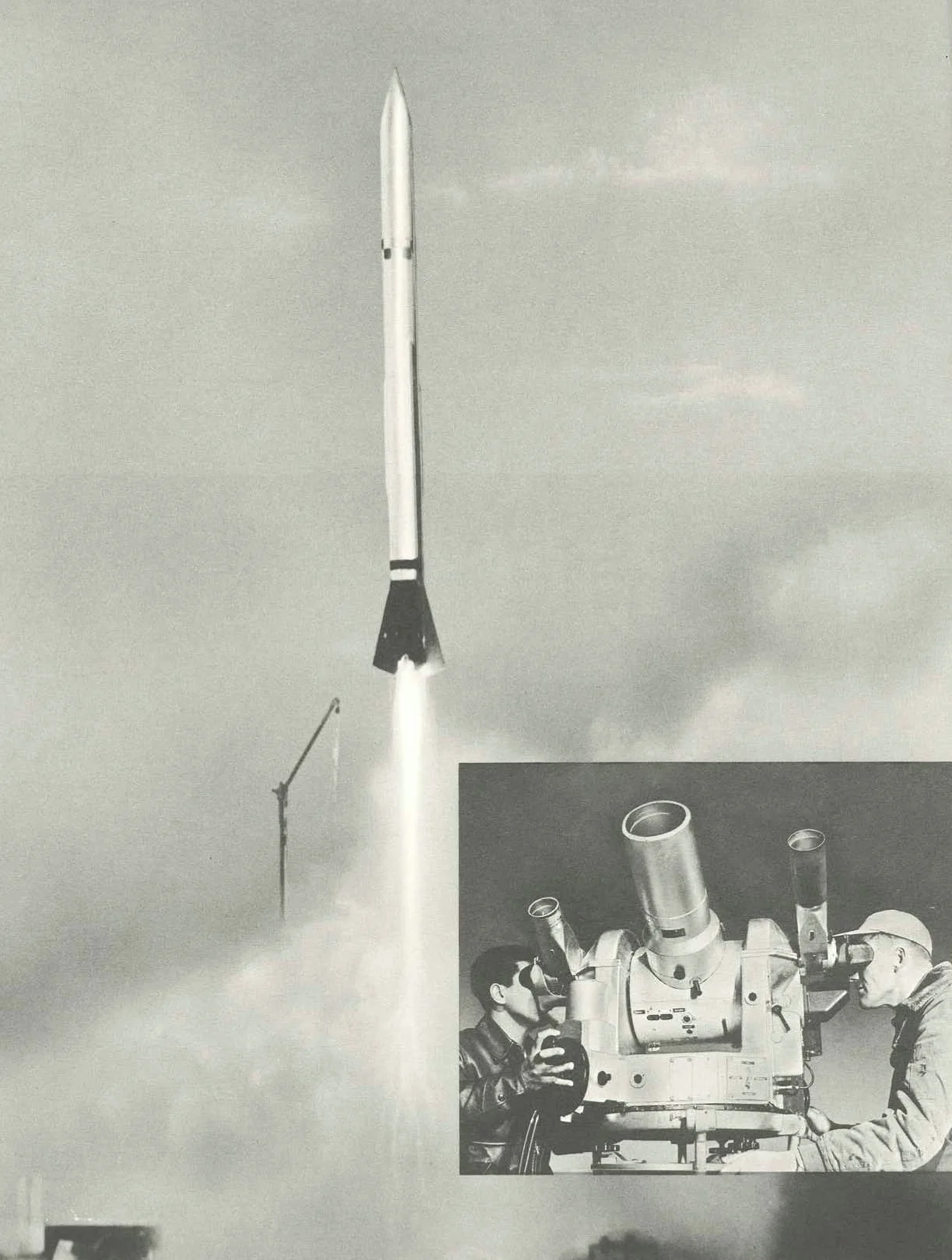

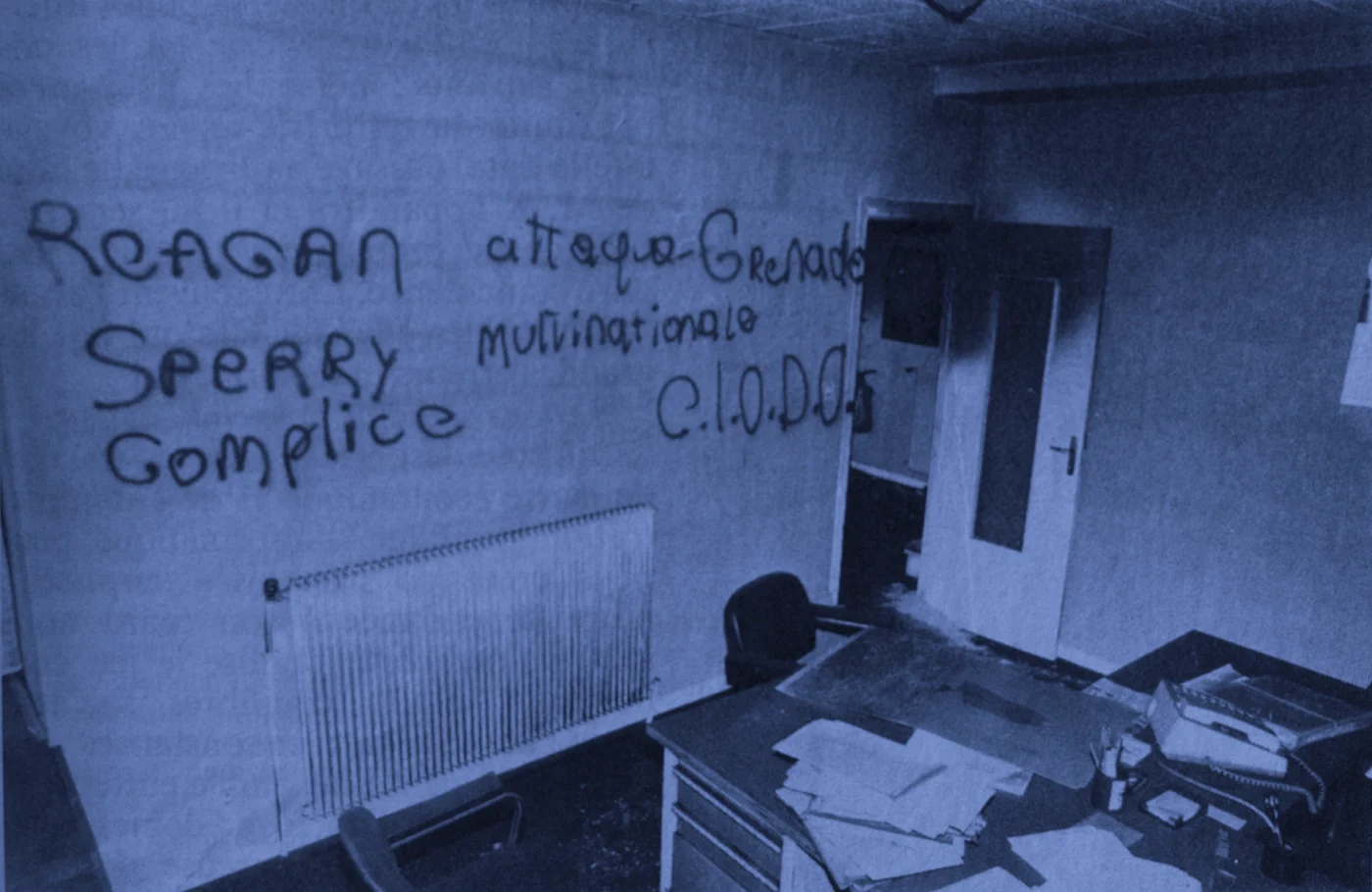

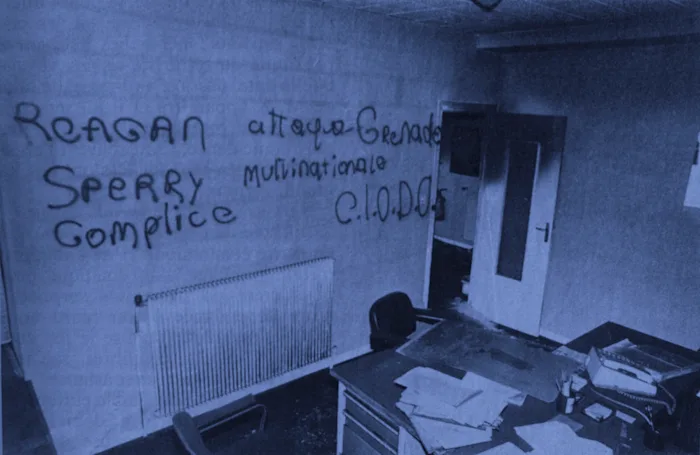

CLODO’s criticism was more prophetic. By the early 1980s, they already saw where the arc of computation was headed. On the one hand, the computer would not stray from the nexus of its emergence, the prototypical device of the post-war military-industrial complex. Their original use had been tied to bombing surveys, anti-aircraft artillery plotting, and atom bomb design. As a direct action group, CLODO targeted computer firms linked to the military, security state, policing, and large-scale industry. On the other hand, however, CLODO had a remarkably prescient sense of what future developments of computation would hold, namely, that they would prove integral in regulating all aspects of social life through a police-like logic. “Informa-flic,” as they put it in one piece of graffiti, penning French jargon for info-policing [informa-tique/flic].

The opening shots in this police campaign can be found in Tom Vague’s quippy biography of the Red Army Faction, Televisionaries. Here we learn that in 1971, when Herold Horst took over the reins of the Bundeskriminalamt (West Germany’s version of the FBI), he was able to implement the “Organizational Principles for Electronic Data Processing in Law Enforcement” that he had outlined just a few years earlier. The official account is that Herold led a systematic manhunt that successfully liquidated the RAF. But according to Vague, Herold became “so obsessed with his computer he moved into the complex so he can be with it all the time.” The result of this obsession was a database of nearly five million names, 3100 organizations, and over two million fingerprints and pictures by 1979. In short, the experiments that were used to develop modern info-policing began with the hunt for political militants.

Thomas Dekeyser: This particular history of computation raised a series of questions about our own fascination, as researchers and filmmakers, with CLODO. Documentarians often see it as their task to shed light on forgotten cases, to establish connections previously overlooked. But this aim feels unsettlingly close to that of the “informa-flics” CLODO sought to condemn. This is why we spend a large portion of our film querying: were we extending the practices of identification, mapping, and correlation the police had initiated in the 1980s when they drew up profiles of CLODO and sat in vehicles outside what they believed would be CLODO’s next nocturnal targets? We saw it as our duty to at least attempt to forgo the urge to “fill the gaps of history” and instead to expand them through the strategic use of secrecy and mystification.

Beyond the sphere of research or cinema, the question of “archive fever” — Derrida's felicitous term for the lure of archiving — is one that, we believe, technological politics needs to take more seriously. As you note, Ian, even the most radical of actions often end up as fresh impulses fueling the digital archive, often pairing images with a call for participation and a list of clear demands. We find an alternative in CLODO's trajectory, which we describe in the film as an instantiation of the “an-archival”: the humorous obfuscation at the heart of their three communiqués, their refusal of “recruitment strategies,” and their self-annihilation after three years. Like the Volcano Group (Vulkangruppe) who, in 2024, set fire to the electricity supplies of Berlin’s Tesla Gigafactory, CLODO sketches the outlines of a technological politics no longer enamored with feeding the network with new resources, preferring instead to starve it. They know well that speaking in familiar words, images, and ideas is too easily converted into the solidification, if not expansion, of our technological present.

IAP: Machines in Flames evokes the entropic ontology of information, which threatens digital and analog records alike. As the film’s narrator makes clear, celluloid is eminently flammable and data centers always risk overheating, burning, and melting into toxic pools of silicon. At the level of software, the film also posits that viruses and encryption offer a means of destruction already logically embedded within the computational means of production and control, weapons that can turn algorithmic machines irretrievably against themselves.

In other sections of the film, an anonymous camera wanders at night between some of CLODO’s targets in Toulouse, drifting across the technogeographic contours of the city. Everything appears imposing, securitized, and controlled, and yet also seems totally exposed and vulnerable to the dark conspiracies that the film suggests lurk everywhere around. We can’t help but wonder, as we watch, if the explosions of CLODO’s past will erupt again on our screens in the present.

In these formal choices, the possibility of attack seemingly emerges from within and yet ultimately against the technologies that administer society. Computation is not presented as another industry in need of regulation or reform, but rather as both the present’s infrastructure of social domination and a reservoir of destructive potential waiting to be ignited. Could you say more about this diagram the film draws between computation and its destruction?

TD: You’re right to draw a connection between the violence of computation and that of CLODO. Each, in their own ways, fan the flames of destruction: computation through its embeddedness in the construction, guidance, and management of war machines; CLODO in the matches, explosives, and flames it weaponizes to undo them. CLODO’s willingness to follow computation on the path of destruction is what sets them apart from other groups who were active around the time, and the reason they caused such outrage. The French Communist Party [PCF] were so appalled by CLODO’s insistence on abolition over reform that they wrote opinion pieces in the newspaper declaring their own faith in computation’s potential in the struggle for workers’ emancipation. For example, they write: “Nothing justifies breaking the tools of labor. [We] underscore, by contrast, the immense possibilities offered by informatics and micro-electronics for the liberation of people from all forms of exploitation and oppression.” Like the 19th century machine-breakers before them, CLODO saw computation’s pretense of liberation as yet another measure of control, whoever’s hands it is in. Destruction is so baked into computation, CLODO wagered, its origins are so tainted with blood (remember: the first computer — the ENIAC — was designed to compute WW2 ballistic firing tables), that there was only one adequate response: to burn it to the ground.

It would be wrong, however, to read CLODO as simply mirroring the taste for destruction it finds in computation. Its relation is not that of a dialectic wherein the militant copies the model, definition, and grammars of what it seeks to dismantle. CLODO took the sparks of destruction in computation and drew them to their extreme conclusion. The computational industries kept all that carefully sustains and nourishes the state and capital — property forms, wage relations, profit margins — outside their firing range. In the hands of the militant group, destruction was detached from the breaks that contain it, becoming almost all-encompassing along the way. CLODO’s hope appeared to be to undermine, at all stages, the organizational forms, rigid programs, and the desire for recognition and recruitment that characterizes the computational industries as much as of the techno-reformists looking to change them. One glance at their playful communiqués and “self-interview” makes this more than apparent. In the end, CLODO went as far as abolishing itself, after three years, never to be heard from again. Contrary to sustaining a dialectical negation, CLODO sought to attack the logic of relation itself, including the constitutive relation to itself. This relentlessness is partly what draws us to CLODO, and why we think of it as having a cosmic dimension. CLODO’s abolitionism is in the modality of a cosmic entropy that swallows whole worlds, accelerating its paths of destruction.

AC: Both of you are hinting at the thing that separates CLODO from so many others — both their enemies, the military-information-industrial complex, and their comrades, the militant anti-imperialist left — namely, their metaphysics (or more colloquially: their “worldview”). They foresaw how computation would weigh even more heavily on our collective consciousness than anything else. Said another way, beyond the part computers play in cooking the planet to death, the greatest tragedy of ubiquitous computation is how it colonizes the mind.

One of the stories that help us frame the film is that of “operations research.” This is the name that the military gave to its “science” of decision-making, which helped make war into an industrial process. Management took the factory model and applied it to killing. Quantification was king. Logistics became the way to win battles, and microeconomics helped war run like a business. The great irony: this management coup was an ideological success, but often led to failure in the battlefield.

Consider an official US Department of War film released in 1944, “The Case of the Tremendous Trifle.” It offers a fictionalized account of the planning behind the US’s 1943 strategic bombing of Germany’s ball bearing industry. Trifling-small things like ball bearings, their case went, are strategic choke points overlooked by anyone not paying attention to the technical inner workings of the new industrial approach to war. Thinking like electrical engineers inspecting a circuit diagram, war planners committed precious resources to a risky bombing raid that cost them planes and lives. The film touts it as a success. But in reality, the ball bearings were so trifling to produce, Germany had already amassed far more than they would ever need. The putatively efficient, scientific approach to war was a wasteful exercise in unnecessary death.

Why do I bring this up? Because it demonstrates how the psychic consequence of computation is a myopic techno-strategic style of thinking. Our culture has been consumed by the fantasy of technical solutions to social problems, which stems from an almost mystical belief in the power of calculation — an overestimation of the importance of concepts like efficiency, simulation, automatic decision-making, data-driven analysis, and more generally, econometric methods. Belief in it is so strong that social life now seems driven by “visionaries” who whip up enthusiasm for computational capacities that do not yet exist, and may never. This signals something dire: even if all the semiconductors of the world would fry tomorrow in a gigantic solar storm, the prevailing way of thinking would not change a bit.

Far too much of the left was complicit in this. Many comrades were both half-right and entirely wrong. The RAF and other militant groups correctly identified industrial computation as a link in the great capitalist chain of computation. But even as they bombed these devices most of them fell deeper into the techno-strategic analysis of global geopolitics of their enemies.

Most refreshing about CLODO is their rejection of such techno-strategic thinking. Unlike the guerrilla, they did not cast their actions in the paramilitary language of strategic campaigns. By speaking mostly through graffiti, they acted decisively against computation rather than debating its merits. And in the sparse writing they did release, they did not condemn computers per se so much as the computer’s world. Their point: we will not defeat the authoritarianism of computers with smarter devices or more enlightened management (e.g. socialist or communist control); the only way through is finding and getting outside the computational mind.

IAP: There’s an interesting distinction between the logic of computation that aspires to calculate and orchestrate each activity and relation across the whole of the planet, and CLODO who desire to attack these computational forms in ways that will not become subsumed within nor reproduce their logic. Could you elaborate on how CLODO pursues a path against algorithmic domination, one which attempts to bypass the strategic thinking and totalizing logic of computation without retreating into isolated blips of resistance that are to some degree always already modeled, predicted, and accounted for by power?

AC: This is a question that often comes up in Q&As after the film. Viewers ask: does CLODO provide a strategy that could be adopted today? We always have to let people down. It seems that CLODO did not have any “strategic” objectives. In the film, we draw an analogy between them and the spontaneous ignition of old nitrate film. In a way, their actions are much closer to a prison riot than a factory strike. Paul Virilio famously introduced the concept of “the integral accident” whereby the invention of the train simultaneously invented the train crash. We move this to the social register: when they began manufacturing computers for hydrogen bomb design, they also began manufacturing CLODO.

Planners typically start fidgeting in their seats after we say this. They cannot abide “local” resistance and demand that it be “scaled up.” But how would that even happen here? In our estimation, CLODO was successful only because they knew the city well enough to think and act like burglars. Blending into friendly crowds is what kept them from being identified or caught. There are ways for others to act in solidarity or even learn from their example, but only if they are taken from a covert-cell or autonomous network standpoint. The lack of a center is what makes these approaches most effective: with no leadership, the forces of repression have to attack the whole network, one-by-one.

IAP: Machines in Flames was released as the first project of the “Destructionist International” (DI), a group whose ideas are articulated in “A Manifesto for Destructionist Film,” which also appeared in 2022. Rejecting the infodoc and its obsession with exposure, the entertainment documentary and its TED Talk catharsis, and the historical avant-garde’s obsolete commitment to estrangement, the DI instead embraces “the negative in all of its forms” and aspires to deploy “visual-conceptual weapons” against the world as a whole. Reading through the manifesto again recently, I was reminded of Guy Debord’s thesis that what was needed was not a negation of style but a style of negation, an approach which the DI has seemingly embraced. In a moment where culture has become ever more invested in the production and circulation of data-rich visualizations, participatory online platforms, and highly polished forensic truths, how does the DI’s turn towards the negative allow us to rethink what film can do (and undo), offering perhaps not new beginnings but a turn towards the end?

AC: There is way more at stake with names than might initially meet the eye. There is a Derridean notion — to name something is to immobilize it, to prepare it for death. Conversely, proper names allow us to address whatever makes something singular.

The name “Destructionist International” did not arrive until we had been deeply immersed in the CLODO project. We asked ourselves a similar question about them as you have about names: what is the “existence” of an entity that could only exist within special conditions? What we found is that there are rare subjectivities that appear in the heat of a moment, but not the cold, harsh world of everyday life.

There is a long tradition of ridiculing minor eruptions like the ones created by CLODO. Leninists charge insurrectionists with infantile adventurist spontaneity, while techno-solutionists dismiss outright anything that resists being “reproduced at scale.” But we are convinced that real change is not driven by politicians and bureaucrats. It is not organizational infrastructure, but interventionist events that are the difference that makes a difference.

We have little patience for the nauseating parade of exposés that fly under the flag of “documentary.” Their one trick is liberal pity: profiling the perfect victim whose story of injustice earns the viewer’s outrage. They claim to be driven by empathy. But that is not what is really going on. It is a voyeuristic, pornographic impulse of taking possession of what can be seen.

The revolutionary forces that will overthrow patriarchy, subvert capitalism, and dismantle racial domination do not need our pity. They are powerful, dangerous, and inherently threatening. It would be a grave error to portray them as weak or pathetic. As such, we refuse to tell stories in which systems of power are the prime mover. We place our fate in the hands of these forces of destruction.

To be a bit didactic, it is the forces of destruction themselves that make up the “Destructionist International.” It is an international without a charter, whose rank-and-file are rarely card-carrying members. Thomas, Dana, others, and I comprise a minor fraction of the international, constituting a temporary cinema committee, literary organ, or whatever — continuing our contributions as long as we feel that there is work that needs to be done.

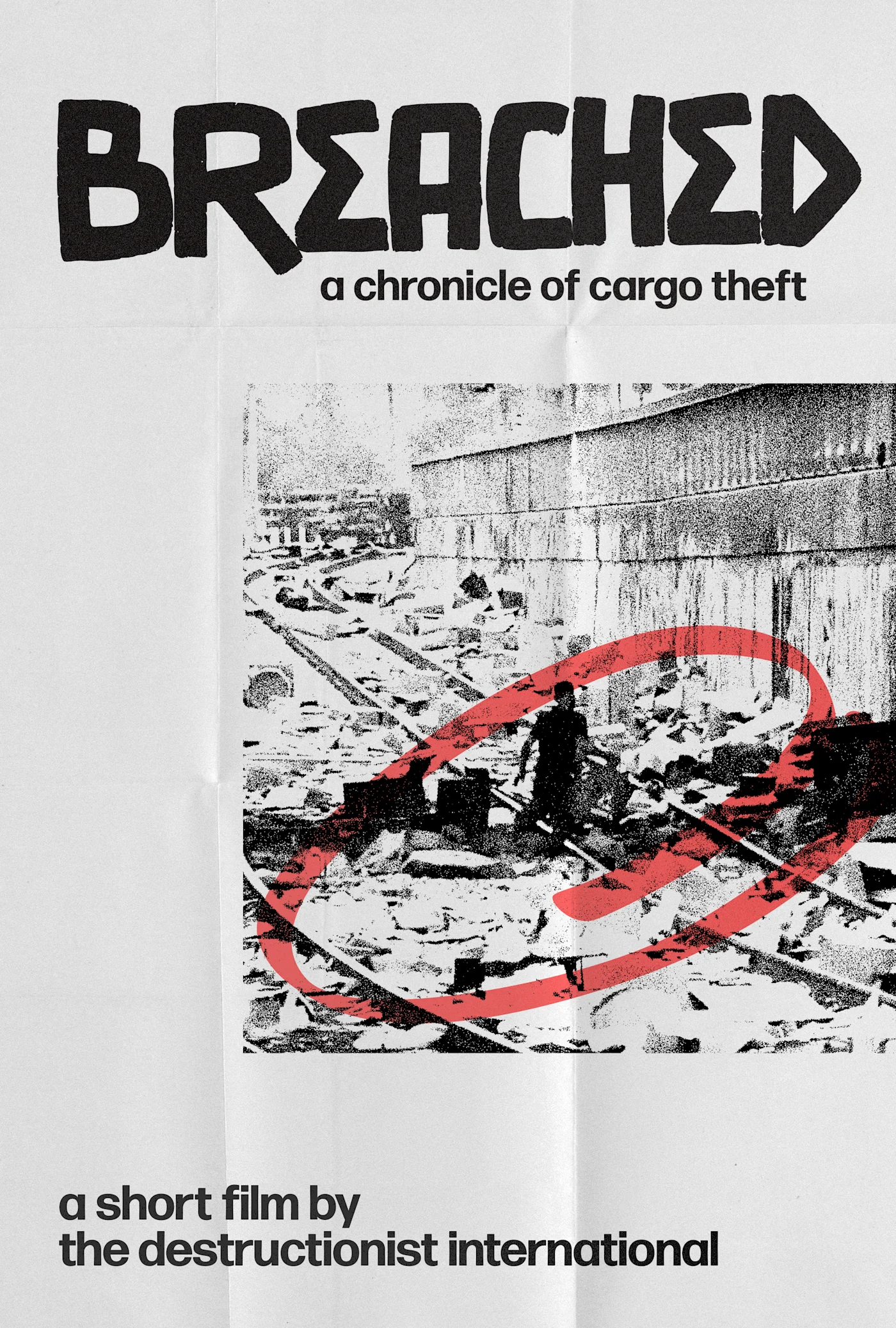

IAP: Following Machines in Flames and the manifesto, the “Destructionist International” has a new film project being released soon titled Breached: A Chronicle of Cargo Theft which approaches the logistical flows and tendons of global capital from the perspective of a disaffected worker. What led you to pursue this new project? How would you situate it in relation to your prior work? What else can you tell us about it, as it begins to be screened?

TD: Like Machines in Flames, Breached follows the traces of a collective usually denied the status of “political subject.” Rather than computer bombers, the protagonists of Breached are looters. In Los Angeles in 2021, these folks identified a crucial bottleneck in the networks of global capital where freight trains were forced to come to a halt. The news spread fast. Organized networks began visiting the train tracks on an almost nightly basis, cracking open containers and emptying their contents en masse. Soon after, images of cardboard-strewn train sides went viral. Representatives of the state, media, and capital descended upon Lincoln Heights calling the scenes an outrage, the sort of thing you might see “in a third world country,” to use California Governor Newson’s words, and which, by extension, must immediately be put to an end by whatever force necessary.

In the film we ask: what makes the container so sacred, and its breaching so scandalous? Why do Americans have a love affair with cowboy train robbers whilst disgracing their contemporary heirs? To examine these questions, we travel across landscapes of logistics, infrastructure, and surveillance, both violent and fragile, guided by a nearby worker recounting his encounters with the looters and the dangerous allure of their actions.

The first “members of the public” to see the film were those who had been most immediately affected by the cargo thefts: those online shoppers whose packages never arrived. We’d found their addresses on the ripped Amazon and UPS boxes whilst filming on the train tracks, and directed them to “The DI Cargo Theft Hotline” where they received a private link to the film. We don’t know what they made of the film, or if they even watched it all. Readers of this interview may be a more appropriate audience. To those who feel this might be true, and may want to organize a screening: we encourage you to reach out to us.