An Eclipse of Invisibility

Luhuna Carvalho

Other languages: Français, Português, Deutsch, Español

The Portuguese publication of Nanni Balestrini's The Unseen (1987) in 2024 by Barco Bêbado Press prompts a handful of notes regarding not the literary work itself, but the context in which it was published.

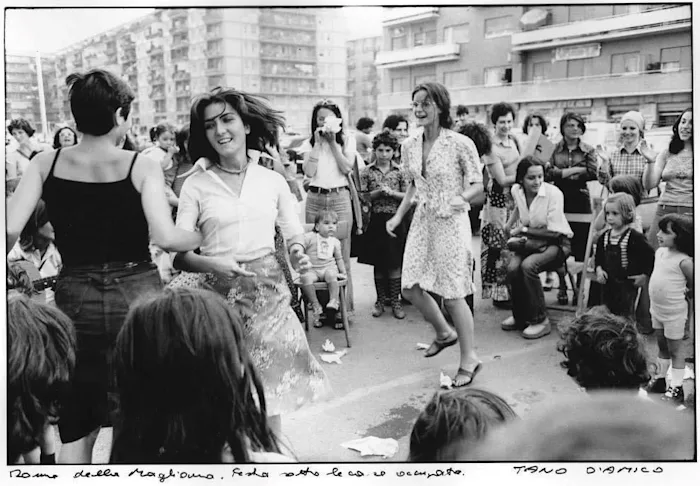

Nanni Balestrini (1935-2019) was one of the main figures of the Italian counterculture, linking the artistic and literary avant-gardes of the early 20th century with the insurrectionary experiences of the post-war period. Perhaps only Pablo Echaurren can match him in producing a pictorial imaginary of 1970s Autonomia, an insurrectionary archipelago of movements, collectives, journals, and assemblies that defied ideological corsets, claiming both a spurious anarchism and a stateless communism.1

In The Unseen, an anonymous young narrator describes the existential process of his militant radicalization, from the high school revolts and the first squatted social centers to the use of revolutionary violence amongst a broader armed struggle. The narrative ends, as it did for hundreds of other young people, in the hell of incarceration.

Balestrini's best-known works are his paintings, which structure the slogans and conceptual repertoire of the period as visual poetry, composing a textual cartography of the movements.

His literary experimentation mirrors this pictorial work. Balestrini chooses type characters — a young worker in the wild Fiat strikes of the 1960s; an "autonomous" youth in the Lombardy hinterland of the 1970s — and implodes the syntactic structure of their verbal narrative, leaving a "rhizomatic" discourse, as one would have said at the time, which expresses the vertigo of the subjective explosion in progress. Contrary to any modernist "flow of thought," such prolixity is externalized, bring it closer to the schizoid verbiage of collective exaltation than to the neurotic introspection of an inner abyss:

the morning we occupied the Cantinone we’d got there very early we’d got there very early in the morning it was Saturday morning and the night before while Valeriana and Nocciola were keeping an eye on both ends of the street Cotogno Ortica and I used a hand drill to drill through the big padlock from underneath where the lock is we sprang the chambers and the padlock fell open so that by the following morning it would be all ready and we’d only need to undo the chain then all along the ditch on the other side of the road we placed plastic bags hidden in the brushwood with stones ballbearings and slingshots in them not too much because inside the Cantinone there was all kinds of stuff we could use to defend ourselves in case of immediate attack.2

Balestrini recreates the language of his time, not of a "historical" time, but of a time suspended in a long, diffuse insurrection. His is therefore an ethnographic exercise more than an experimental one. Compare any of his paragraphs with some of the period’s documents, such as the famous text on "use value" written in 1979 by the recently deceased Franco Piperno:

Use value is the rejection of a fixed job, even if it's next door: it's the horror of work: it's mobility: it's the escape from performance as active resistance to the commodity, to becoming a commodity, to being possessed by the movements of the commodity. [...] Use value is the desire to learn with the whole body this new sensibility that emerges from this continent rich in tones, nuances, sensitive emotions that are youth associations in their particular relationship with music, cinema, painting. [...] Use value is the obstinate search for new relationships between men, for a "transversal way of communicating," of experimenting, of growing on diversity itself. [...] Use value is the "attentive joy" that comes from stealing useful, desired objects — which is the direct relationship with things, freed from the dirty and useless mediation of money [...] Use value is the naive hope with which thousands of "counter-economic" experiments are born in agriculture, in services, in neighborhoods, only to live a fragile existence and then perish. [...] Use value is the inhuman abstraction of murder, of an attack — an imaginary solution to a real problem, a dense regret at one's own power, a desperate attempt to assert, with impatient pride, one's own social strength.3

Balestrini responded to the uniqueness of Autonomia’s political forms. The exceptionality of the Italian ’68 lay not in the fact that it "lasted ten years," but in how, within that period, it managed to rehearse an internal rupture in the very category of "politics." Imagine a long, drawn-out PREC4 wherein a deepening of the experiences of "popular power”5 went beyond a logic of participation and economic development, taking on its own collective experience as a program, transforming lived experience into an instrument of subversion in itself.

The intense acceleration of the "Italian miracle" made subjugation to the time and space of the big factory particularly obvious and brutal. All socio-economic identities — being a "worker," being "unemployed," being a "woman," being "young," being "marginal" — these became categories of confrontation between capitalist domination and a class antagonism. The response would also be "immediate": We want everything, as Balestrini himself put it. The protest refused all social mediation — trade unions, parties, etc. — opposing to them an archipelago of refusals, the so-called "area of Autonomia." Not the "autonomy" of self-management and workers’ control, but an "autonomy" that refused the entire productive process.6

The Unseen traces the final stretch of that decade. The euphoric insurrection meets its limits in the armed confrontation with the state and the Italian Communist Party. Thousands are charged with terrorism, hundreds driven into exile in France. It is as a collective bildungsroman that The Unseen becomes a mythical text, one of those that, read at the right age, transforms a life. The book is literally a manual of subversion, instructing us how and under what circumstances a rupture with activist bureaucracy can create a community capable of escalating a struggle.

Today, however, a lucid and attentive look at the text will find in it more mourning than myth.

The furious communal excess of The Unseen would be impossible today. Anyone straying into it would be immediately identified and prosecuted. The extension of the objective and subjective means of social control has dissolved any “invisible” metropolitan counter-power, which was extinguished without even realizing it.

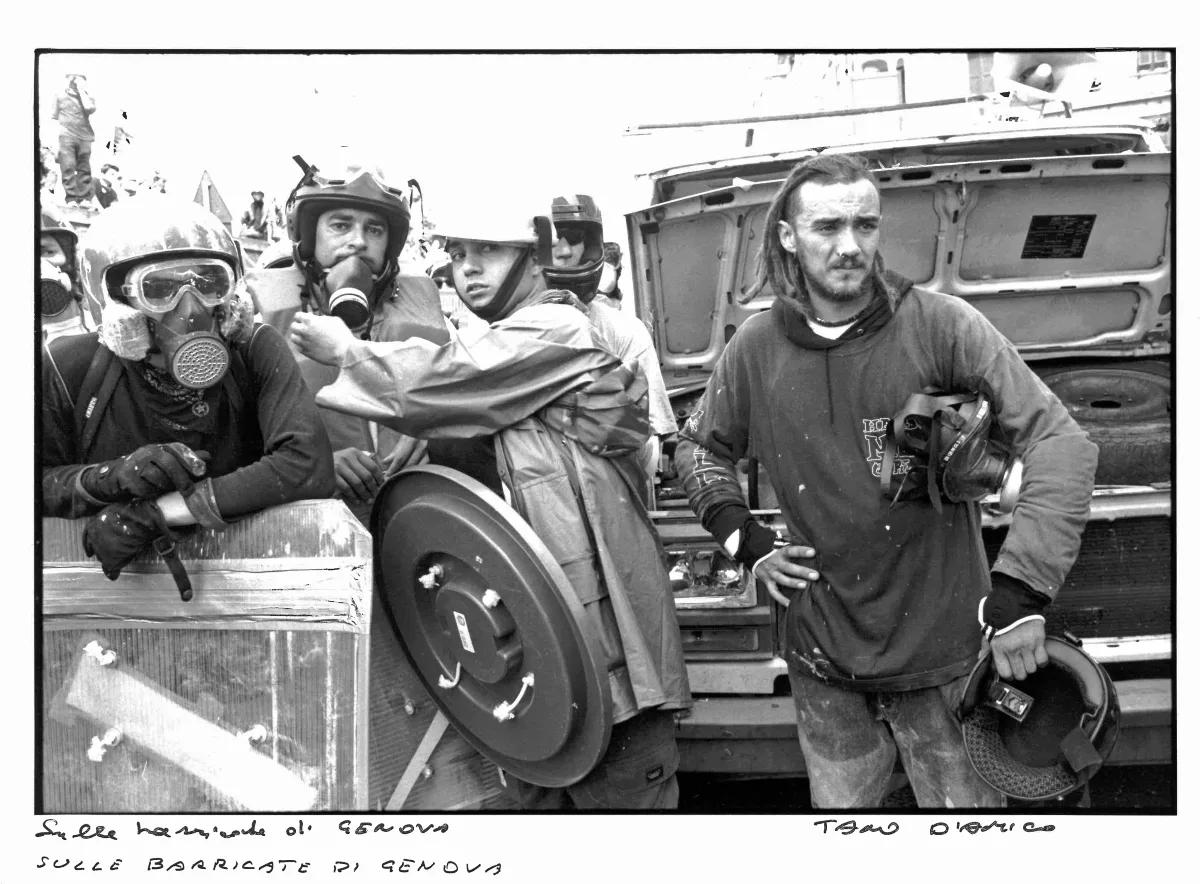

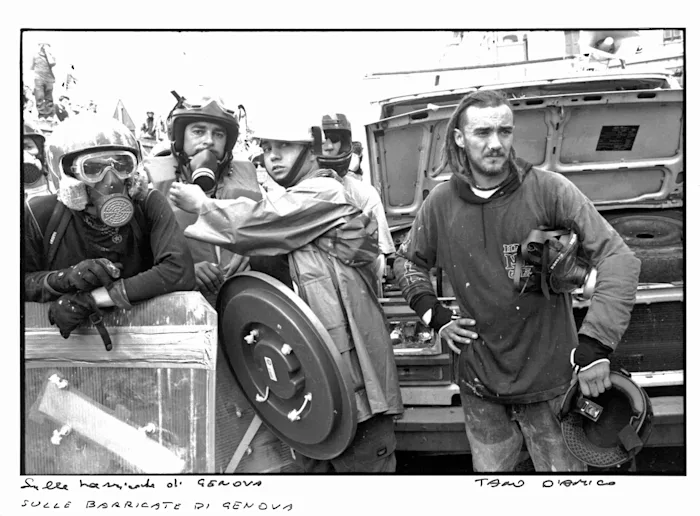

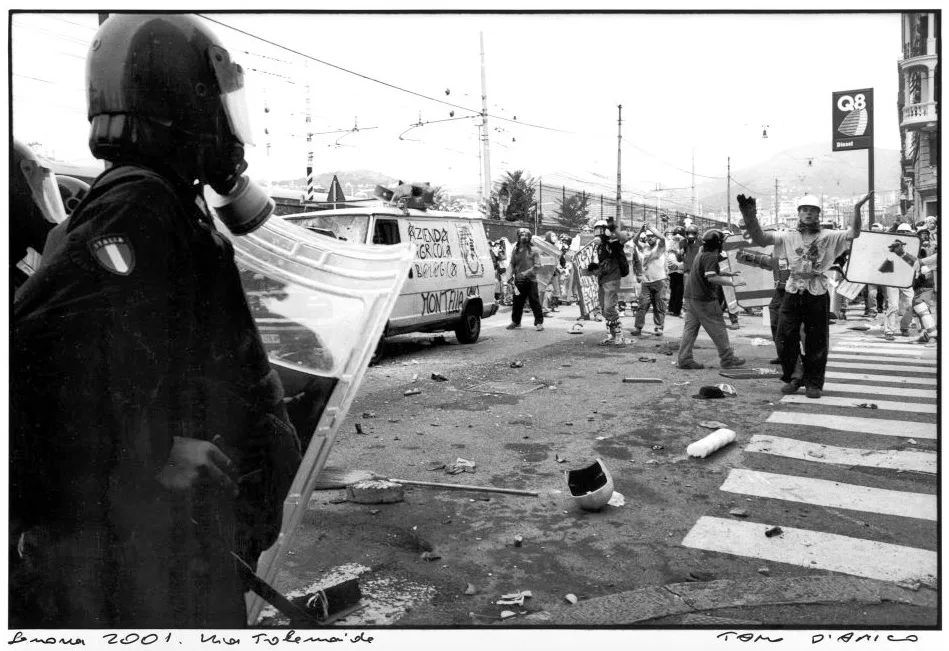

That's why the decision to include, in this Portuguese edition, a deeply anachronistic 2005 preface by Antonio Negri was so strange. Negri is rehashed in order to lend his prestige to a text that not only doesn’t need it, but is even diminished by it. Negri associates the vitality of the “Unseen" with various contemporary movements (Pantera, the Italian student movement of the 1990s, and the massive anti-globalization mobilizations in Seattle, Prague and Genoa), claiming that the book is an anthropology of a coming "multitude," drawing a line of continuity between the 1970s and the new spring of movements. If this kind of statement was common in 2005, in 2024 it sounds like a cruel joke.

A certain harmony between the formal and informal institutions of the left (the so-called "movement") and the diffuse forms of social antagonism seemed somewhat "natural" until the explosive succession of revolts and insurrections that followed the financial crisis of 2008, at which point a divorce slowly began to emerge.

In 2011-2012, in the occupied squares of Madrid, Lisbon and New York, "movement" and antagonism seemed indistinguishable. A few years later, in 2019/2020, during the Yellow Vests and the George Floyd uprising — both described as the biggest revolts since 1968 — they became distinct entities: the impact of militant institutions on the development of both events was relatively nil. On the one hand, there were the "social movements," folklorized, bureaucratized, and self-referential, incapable of thinking beyond representative politics, a banal catechesis of good feeling combined with an autophagic judicialization of their own milieu. On the other side, one had the "savage" masses, increasingly proletarianized and deprived of form, illegible through the political categories of liberal society, simultaneously too revolutionary and too reactionary, humiliated and hated by progressivism, averse to any paternalism, prepared to blow up the whole house for lack of any remaining emergency exit.

The most apt remark concerning Negri's preface, and the decision to republish it, was made recently by his former compagnon de route, Maurizio Lazzarato:

There were those who raved about the autonomy of the cognitive proletariat and the independence of the new class composition. Nothing could be further from the truth. Those who decide where, when, how, and by what means labor power is produced (waged, precarious, servile, slave, female, etc.) are, once again, those who possess the necessary capital, who possess the liquidity and the power to do so. It's certainly not the weakest proletariat of the last two centuries. Far from any "autonomy" and "independence," the reality of the class lies in a degree of subordination, subjugation, and submission never before seen in the history of capitalism. To exist as "living labor" is a disgrace, because it is always dominated labor, like my father's and my grandfather's. Labor does not produce the world. Labor doesn't produce the world, but the world of capital, which, until proven otherwise, is something quite different, because the world of capital is a world of shit.7

What remains to be thought is the discontinuity between our time and Balestrini's.

The general promise that a “different left," more libertarian and democratic, would be prepared to replace the "old left,” state-centric and authoritarian, gained new impetus after 1989. The fundamental premise, which found various contradictory expressions, was that struggles themselves, in their very essence, would constitute the emancipatory forms to come. The social and organizational experience of social movements and their counter-culture — apparently open, dynamic, democratic, creative, inclusive, and horizontal — constituted a rehearsal of the politics to come, freed from social democratic and/or Soviet determinism and productivism.

The reorganization of capitalism may have extinguished the working class of yesteryear, but new forms of labor contained the same desire for democracy, justice, and equality. The numerous attempts to rebrand contemporary class compositions (the precariat, the cognitariat, etc.) insisted on class struggle anchored in the productive process while, at the same time, seeking to overcome the classical forms of working-class identity (male, white, workerist, etc).

The essence of the left now resided in a creative multiplicity led by a composite subject who demanded, above all, a new type of social contract. The emergence of "movementism" announced a transformation in the very conception of organization and vanguard. Movements abandoned vulgar Leninism, developing and experimenting internally with a practical and critical repertoire that would wait for the inevitable systemic crises to constitute itself as the hegemonic form of struggle.

The militant practices of the late 1990s, from black blocs to social forums and occupations, would end up informing mass mobilizations, first in the anti-globalization movements of Seattle, Prague, and Genoa, and later in the Arab Spring(s), in the occupied plazas and anti-austerity movements of Southern Europe, where a protesting multitude adopted the critical and antagonist repertoire of the militant milieu.

However, the past decade has made it painfully clear that this entire political framework has largely been defeated. The wit and ingenuity of all these ready-made class compositions ultimately concealed the existential instability of a middle class confronted with its inevitable pauperization. Faced with the austerity programs of the 2010s, the same progressive and cosmopolitan petty bourgeoisie that had understood the financial crisis as a systemic exhaustion of capitalism realized that it had, in the end, far more to lose than its chains.

For a large part of the middle class, the consequences of the crisis were for the most part economical, giving rise to their populist and authoritarian chauvinism; but for the post-’68 literate, creative, and intellectualized middle class, what was at stake within the neoliberal cuts in state spending was above all their symbolic and cultural capital.

Their diffuse program then changed from questioning the limits of liberal democracies to a fierce defense of public institutions. Economic realpolitik forced the progressive middle classes to abandon their supposed political passion for "real democracy," casting aside any remaining revolutionary fantasies, and leaving only an enormous anxiety to prove their social necessity and their value as an intellectual and cultural elite.

The "multitude" that, half a decade earlier, had demanded the ousting of all governments in occupied plazas could now be found on social media demanding more laws, more state, more subsidies, and more institutions, revealing itself to be ever more conservative the more that it strutted its “progressivism” as a civilizational achievement.

The historic separation between "movement" and antagonism occurs in this reconversion of the post-68 intelligentsia to raison d’état. The 2019 Yellow Vests protests in France saw the emergence of another middle class in crisis, proletarianized and peripheral, which resorted to "movement" repertoires (occupation of traffic circles, direct democracy, autonomous media, confrontations with the police) without expressing itself within the symbolic, referential, and moral frameworks of a "left" that had, in the meantime, become totally incapable of understanding who the pagans who ravaged the Champs-Elysées were.

The cosmopolitan, liberal, progressive "left," with its modernist subjectivity — heiress to Nietzsche, Marx and Freud, born of the sexual revolution, with poetry falling in the streets and with the day beginning whole and clean8 — became a prime defender and bulwark of the status quo.

The corollary of this depoliticization of the left was its enthusiastic adherence to state management of the pandemic. Its vaunted post-structuralist and decolonizing syllabus vanished into thin air as the scientific validity of lockdowns became the only possible discussion. The total cancellation of any political, existential, or social consideration of the public management of the pandemic demonstrates how impossible any critical or philosophical inquiry that goes beyond a naturalization of the state has become. The pandemic fused this anarchic, democratic, horizontal, joyful, and creative left with sovereign reason, in a historical process that is still complex to grasp today.

In the language of modern political philosophy, state authority is justified by the alleged need of council between subjects who, in their "natural state," would be left to the violence of the law of the strongest. State power is made from the power conceded to it, ensuring that it is always stronger than the strongest among us. As a sum of legal and sovereign institutions, the state draws together individual interests, repressing some, encouraging others, while systematizing them into a collective enterprise. “Society" is but the field of mediation between disparate and antagonistic spheres of interest: a set of instances of participation and open debate, under constant criticism and incessant reconfiguration. In other words, it is the permeable and plastic systematization of "civil society" that legitimizes the ruling power of the state.

The threat to this covenant is then no longer the myth of "the strongest," but those who, for one reason or another, evade full participation in the social contract, refusing their civic obligations (participation, taxes, obedience to authority, etc.) and/or their cultural and symbolic obligations (religious, political, cultural, linguistic, racial, gender-related, etc.). If conservative civil society fears the foreigner, the dissident, the minority, etc., then progressive civil society fears the tycoon, the mobster, the hooligan, and so on. The state would then be the institution that protects us from a violence that is always latent and imminent, whether it issues from below or above. But if anything has become clear of late, it is that the violence projected is often the violence of the projector. The confrontation between universal mediations and singular interests is inherently violent.

This occurs in a twofold process. Firstly, "society" itself, as an abstraction, as a primary mediation, functions as the necessary subsumption of all social relations that are incompatible with its normative framework. In other words, if abstract society needs concrete institutions (education, family, religion, culture, parties, ideology, etc.), it also needs to autonomize itself from their particularity. Society must be protected against the risk that these institutions themselves might split off from the field of abstract mediation. Although the process of social constitution might be endless (since the normative subsumption of spontaneous communities is a continuous task), there is nevertheless a clear political teleology inherent to the idea of society: the creation of a purely social and abstract being, an rigorously civic identity.

Secondly, this abstract social form obviously corresponds to a productive purpose, that of fostering the circulation of value. It is this purpose that sets in motion the social paradigm of the continuous constitution and destitution of concrete communities. Primitive accumulation is not a historical episode in the constitution of capitalism, but a process internal to its own reproduction: the creation of new products, new markets, new capital and new labor forces entails the destruction of old ones.

On the one hand, the purpose of "society" is to facilitate and accelerate the wild vertigo of the circulation of capital, and, on the other, to manage the social short-circuits that ensue, authorizing some and repressing others. Processual spontaneous violence is presupposed from the outset, and even encouraged, organized, compensated for, so as to be redirected and contained. In other words, capitalist societies must guarantee social peace in the same way that they wage their social war. Their guarantee of order is at the same time a guarantee of anarchy.

The perfect society would not produce social peace but an ideal crisis wherein the maximum possible productivity coincides with the maximum possible social atomization. The ideal social subject is one who has managed to make his productive identity indistinguishable from his civic identity. The COVID 19 pandemic was an approximation of this ideal crisis. The subject totally territorialized by the sovereign order was at the same time the subject totally deterritorialized by the brutal acceleration of information flows. The anarchic power of the state merged with the authoritarian anarchy of networks, and vice versa. Both these functions have acquired an historically unprecedented technical capacity, becoming indiscernible and contiguous. Millions of people are safe at home indulging in the most delirious, voracious, and addictive technological onanism, their cynical and iconoclastic anarchy becoming indistinguishable from absolute obedience to the language of the state. This was the Aufhebung, the simultaneous realization and overcoming of the tension between the individual and the group that constituted liberal societies. Order became anarchy precisely as order. Trump and Musk destroy the state while anarchists create legal regimes.

It is in this context that the classic categories of politics and sociology become obsolete. “Left,” “democracy,” “public opinion,” “civil society,” “culture,” etc., mean very little today.

Post-’68 terminology was obviously not liberal terminology, but it was nevertheless an attempt to reformulate it: to "deconstruct" it, to "deterritorialize" it, to "profane" it, to "denaturalize" it, etc. What remained after the abandonment of the socialist project was an attempt to spice up the political and cultural phenomenology of capitalist social relations.

The conceptualization of new mediations and the abolition of all great narratives breaks down with the decomposition of the liberal world. The program implicit in "theory," whether French, German, or Italian, survives only as a cynical awareness of ruling nihilism. A diffuse recognition that we are governed by fundamentally apocalyptic apparatuses has given way to a desperate fascination with the absurdity of the whole situation. The contemporary subject knows perfectly well that their life is governed by a regime of contingent abstractions that devastate them incessantly, but they reserve, as the last vestige of self-property, an intellectual infatuation with their own cynicism and sarcasm. This onanistic narcissism is the only remaining lifeboat, and upon it we drift across an ocean of boredom, anxiety, and despair.

The Unseen reveals itself to be the ruins of a myth. Its formal experimentalism is ultimately ancillary to its narrative structure. The main character is less the narrator than his verbal stream, and as such the minor plot lines become accessories to the literary exercise itself.

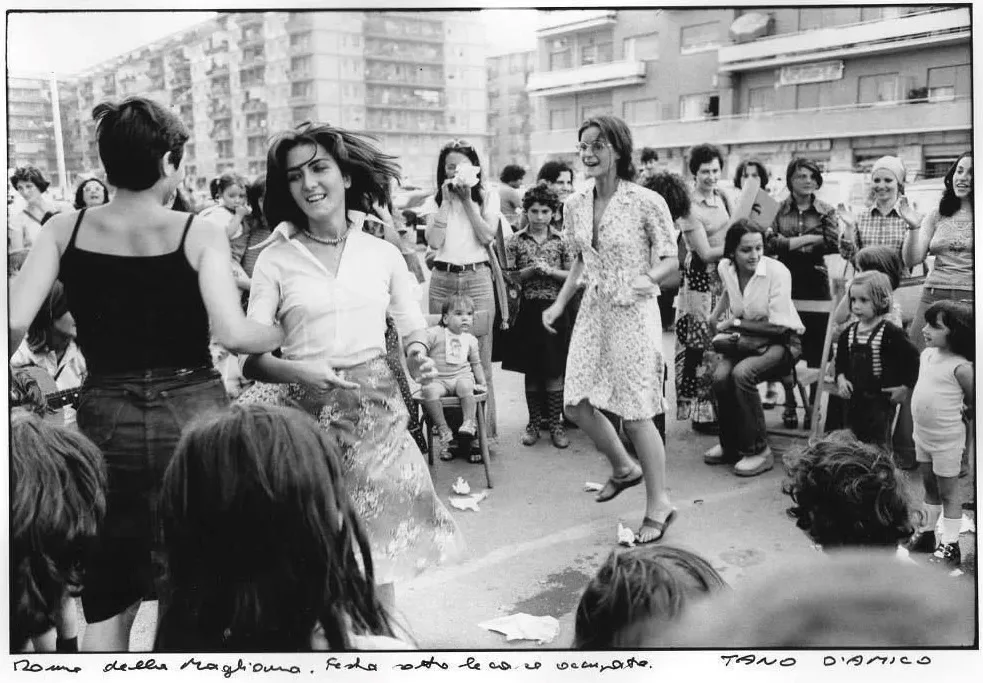

Crucial elements of the period, such as the emergence of a feminism that was autonomous to Autonomia itself, or the widespread diffusion of heroin use, are treated like circumstantial anecdotes. But almost four decades on, what remains to be thought about Autonomia is not its brute insurrectionary vitality, widely discussed and celebrated, but what it already contained within it of a decomposing social world.

The challenging of charismatic leadership, of Guevarist and Marxian bravado, of the manipulative hedonism of the sexual revolution, and of the movement's own discursive practices affirmed a feminine difference, an anthropological otherness, to the male world.9 Even if its gender essentialism should be debated, its practices warrant attention: a common exercise of thought and otherness constituted by a slow refusal rather than a histrionic opposition. The practices of self-knowledge, the long conversational and confessional sharing, the making common (and not “public”) of what was personal, wrought the slow weaving of a language and a gesture that overcame both panic and cynicism.

The use of heroin during the movements’ decline reinforces this point. It was the struggle’s exhaustion that led thousands of young people to the use of a substance that recreated the existential and emotional plenitude they had felt within its communion. Addiction didn't happen out of weakness, maladjustment, or hedonism; on the contrary, it was a conscious decision concerning the ruin of the movement and the intolerable ultimatum between the despair of armed struggle and the condemnation to a “normal life." It is this anti-heroic nature that makes the gesture worthy of further attention, as the "strategy of refusal" taken to its ultimate physical limits. The opiate epidemic that followed the revolutionary movements of the 1970s both anticipates and explains the contemporary opiate epidemic.

An unwritten book exists within The Unseen. It contains all those experiences of Autonomia that proved impossible to translate into Balestrini's literary artifice (or the conceptual structure of “autonomism”), and which are still searching for their own language: an ineffable mismatch between the ecstasy of insurgent communion and the mundanity of politics and everyday life. The necessary "revolutionary books" are those that tell the truth of an era. Ours is not one of overflowing communizing joy, but of defeat.

The coming years promise a rise in radical and violent dissent, but one devoid of form and consistency. If, in the recent past, there was indeed something disruptive in the immediacy of the sensory and psychic experience of exploitation and submission; if it was precisely the body, as desire and spirit, that expressed an alterity to the violence of the factory and the state, today social control through algorithms has created its own endocrinology.

What remains is a "discipline of attention.”10 To be present in the eye of the hurricane, suspending all cynical judgment that binds us to the disenchantment of our time, while replacing it with a contemplation whose attention is in every way contrary to the urgency and blackmail of a hyper-presence that impresses itself upon us like a knife to our throats. This attention must seek to discern which incipient fissures could become significant contradictions. Such fissures emerge amidst what is most intimate and unspeakable in our lives, not because it is secret, but precisely because it is ineffable.

It is necessary to undertake a long and winding "inquiry," not into the conditions of production but into the conditions of subjectivation and desubjectivation. It is from this attention that a new language can emerge. The immediacy to be reclaimed is not that of my desire, of my psychic compensation, of my anxious urgency, but that which precedes my sense of myself. It is a program as faint as the lightest key on an old piano, but it will be the only piano to sound on the barricades.

First published in Portuguese April 5, 2025. Translated into English by the author.

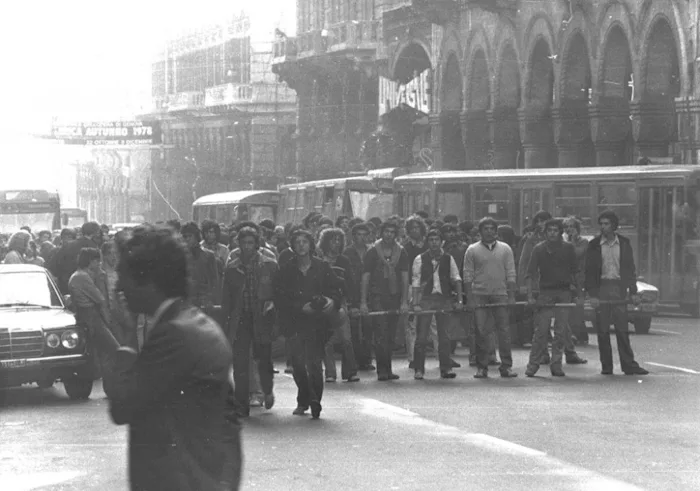

Images: Tano D'amico, and others.

Notes

1. On the history of the period in question, see Marcello Tarì, Autonomie! (forthcoming in English), and Nanni Balestrini, Primo Moroni and Sergio Bianchi, The Golden Horde, Seagull Book, 2021 (an excerpt is online here). On Autonomia’s artistic imaginary, see Jacopo Galimberti, Images of Class. Operaismo, Autonomia and the Visual Arts, Verso, 2022. ↰

2. Nanni Balestrini, The Unseen, trans. Liz Heron, Verso Books, 2012, Part I, §8. ↰

3. Franco Piperno, “Sul Lavoro non Operaio,” Supplement to No. 0 of the magazine Metropoli.↰

4. The “Processo Revolucionário em Curso” (PREC) refers to the period between March and November 1975 when struggles in Portugal reached their most intense point. See Luhuna Carvalho, “Portugal 1974/1975,” Endnotes, 2024. Online here.↰

5. During the PREC, factory, neighborhood, and rural assemblies were referred to as “Popular Power.”↰

6. “Today's social science is like the productive apparatus of modern society — everyone participates in it and everyone uses it, but the only ones who profit are the bosses. You can't destroy it — they tell us — without sending man back to barbarism. But first of all, who told you that we care about the civilization of man?” Mario Tronti, Workers and Capital (our translation).↰

7. Maurizio Lazzarato, “Why War?”, Ill Will, October 16th, 2024. Online here.↰

8. Sourced from a poem from the Carnation Revolution. —ed.↰

9. Italian feminism in the 1970s was vast, ranging from the Marxian theory of social reproduction of Federici, Fortunati, and Della Costa, to the various shades of separatism in Carla Lonzi, the magazine Sottosopra, and the Milan Women's Bookshop Collective. See Carla Lonzi, Let’s Spit on Hegel (online here) and Libreria delle Donne di Milano, Non Credere di Avere dei Diritti [Don’t Believe You Have Rights].↰

10. "By communism we mean a certain discipline of attention." Anonymous, Call. Online here.↰