Anarcho-Blackness: A Conversation with Marquis Bey

Marquis Bey

In the summer of 2020, Marquis Bey published Anarcho-Blackness: Notes Toward a Black Anarchism with AK Press. Released hot off the heels of a nationwide uprising against white supremacy and the police, the book stages an encounter between blackness and anarchism that offers insight into the spirit of that rebellion and others to come. The occasion spurred the following conversation, beginning in 2020 and wrapping up in the final months of 2021. In it, we discuss fragmentation, unsettled notions of blackness, being held accountable, and more. Marquis Bey’s next book, Black Trans Feminism, is due out January 2022.

Part of our ongoing series Desertions, which maps the manifold forms of treason, refusal, and defection from dominant images of community.

Ill Will: In your Anarcho-Blackness: Notes Toward a Black Anarchism, you write that:

To infuse anarchism with anarcho-Blackness is to push anarchism’s logics further. Many anarchists did not organize on the grounds of difference and differentiation, even as they sought ways to prevent their silencing. Hence, anarcho-Blackness supplements these oversights via an insistence on perhaps assemblage, or swarm, or ensemble, whereby there is a consensus, or consent, not to be individuated — which is another way to say an affirmation to emanate from difference toward the insistence on collectivity and agential singularity.

If I’m understanding this correctly, you seem to be arguing that the path forward for revolutionary struggle lies not in ignoring or sidelining internal differences in the name of a common enemy (as previous generations of revolutionaries may have done), but rather in consciously composing ourselves in such a way that these differences do not become markers of unique individuals, but serve rather as properties of a more robust, resilient crowd. This reminds me of a reflection on the Yellow Vest movement in France, in which two participants theorized the source of the movement's resiliency:

Considered in itself, donning a safety vest carries with it no unifying ideology, principle, or demand, nor any particular subject-position or identity. It operates as what we might call a ‘meme with force’. A meme does not necessarily alter the content of a struggle. In France, for instance, the catalyzing factors are without a doubt eminently familiar social pressures, such as the rising cost of living, diminishing social mobility, cuts to public services, a triumphant neoliberal government who spits in the eyes of the working poor, etc. What the meme of the Yellow Vest offers is a malleable form within which this content can assume the force of an intervention. [...] The fluidity of the meme makes it possible to join a march, a blockade or a roundabout occupation without having to buy into a ‘common interest’ or the legitimizing beliefs of a movement. It does not solve, but simply defers the question of a common grammar of suffering to a later point. [...] This question being, can people whose lives are defined by incommensurable modes of violence experience the same world, the same language, a shared vision of freedom? The meme neither resolves nor suppresses this incommensurability — there is no shortcut to an existential commons. What it does, rather, is unleash these differences from any prerequisite of unity, by interrupting our comparative habit of legitimating suffering by weighing one of its forms against another. The yellow vest opens the field of politics: suddenly the center is everywhere, and everyone can attack and get organized for their own reasons, irreconcilable as they may or may not be.

Given its level of political polarization, do you think that this notion of “deferring” questions of difference makes sense in the U.S. context?

Marquis Bey: This is a wonderful comparison to make. I think there is a generative synergy between my understanding of anarcho-blackness and this idea of a “meme with force.” So thanks so much for making that connection. To the possibility of “deferring” questions of difference in the U.S. in light of political polarization, it is, of course, tricky. Surely there is utility in a solid, united front — strength in numbers and all that. I don't want to discredit a utilitarian approach to change-making, for I imagine there are many who care less about everybody within the group having their identities or desires or niche proclivities met, and care more about, essentially, “Are we getting shit done? Yes? Cool. No? Not cool.”

But I think I am still committed to a different way of approaching politicality. And I think it is more than an Audre Lorde-esque mobilization of differences as our strength rather than our weakness. I am trying to express a way of thinking about the very presence of fractures within a demographic or organization as itself a way of doing politics. In other words, the move toward fracturing, toward dissolving the purported cohesion of a group — what someone like black critical theorist Nahum Chandler would call, following Derrida, “desedimentation” — strikes me as politically desirable. It is because this desedimentary movement signals a refusal of the violence of that which imposes a monolith or circumscription, which can be given the name normativity. So I want to mobilize and find solace in the non-normative (not the “anti”-normative), because it marks the refusal to abide normative, circumscriptive, nonconsensual impositions.

And this is the “anarcho-,” the anarchist “No Gods, No Masters.” It is not merely a niggling contrarian but a Socratic gadfly, an irreverence toward law and order and hierarchy and wholism, because only in perpetual openness do we continue to ask and interrogate, and only when we ask and interrogate can things be something other than this.

IW: This image of “desedimentation” helps me to visualize what you're referring to. I'm imagining the cold, stagnant bottom of a pond being disturbed by some little turtles looking for a winter getaway, stirring up all kinds of seemingly-uniform sediment into particles that combine and fall to the bottom in new forms. This last part — the proliferation of new mixtures, the “something other than this” you allude to — feels like the key part of that process though, but one that often seems like an afterthought for many anarchists. Given how deeply social life (and the ecological sphere that supports it) has been fragmented over these last few years — often at the hands of our enemies in D.C. and Silicon Valley — I don't think we can afford to be content with the nihilist Schadenfreude that comes with watching the world fall apart. If anything, that process seems like it has rapidly accelerated to such a degree that outright civil war — total desedimentation — feels almost like a given at this point. But what then?

I'm reminded of a passage from Now that elaborates this path a bit:

At the cost of accepting fragmentation as a starting point, it can also give rise to an intensification and pluralization of the bonds that constitute us. Then fragmentation doesn’t signify separation but a shimmering of the world. [...] Realizing the promise of communism contained in the world’s fragmentation demands a gesture, a gesture to be performed over and over again, a gesture that is life itself: that of creating pathways between the fragments, of placing them in contact, of organizing their encounter, of opening up the roads that lead from one friendly piece of the world to another without passing through hostile territory, that of establishing the good art of distances between worlds.

How do you imagine that we could proceed from this point of utter fragmentation – nascent civil war – towards a horizon of re-composition, of organizing our worlds on our own terms? What pathways need to be created?

MB: I love that image of the turtle in the pond. It’s such a quiet but profound image to me, so thanks so much for that, truly. Too, I love the Now quote — a shimmering of the world. Mm, lovely.

What is fragmenting is the very ground on which we walk. Indeed, desedimentation breaks apart and dissolves the sediment on which many things we know and love rest. So to loosen and fracture that means that we are walking on...what? Nothing. And how can we find footing on nothing? It seems like we lose so many things that were comforting to us.

But I do not see this as negative. In fact, it seems to me that the very ground on which we were walking, and the foundation on which many of our structures and things rested, were toxic, to put it bluntly. Sure, we are in deeply unfamiliar territory when we undermine the ground and sure we are lost — which is to say, we don't recognize anything around us — when things are utterly fragmented. But that is precisely the beginning of another possibility, another kind of life we might hope to live, a life that is, in its departure from what has been given to us currently, fundamentally not this. Why would we wish to recognize our surroundings when our optics for recognition cannot currently account for what might be radically new and otherwise?

Having no footing and fragmenting things is to me the mark of an actually radical movement toward radically reconfiguring (or obliterating or destroying in service of creating, à la Bakunin) sociality and what it means to be with one another, to relate to one another much differently. We must create under-the-radar and submersive (submergent and subversive) pathways, indeed pathways that do not look like pathways. They might look like digital spaces, or sub-sub-sub-reddit forums, or basement study sessions with drop-outs and adjunct professors and grad students and vernacular thinkers with their toddlers, or conversations in the kitchen over the preparation of food, or in the office over the water cooler or during a smoke break while you’re stealing company time.

IW: You’re certainly right about the terrible discomfort of this groundlessness. For many, this last year took some of the last “simple things” away from us that we never thought could disappear — the ability to gather some friends together on a porch without fear or guilt, to open a window without tear gas or wildfire ash seeping inside, to plan a modest future with our loved ones without having to factor in the prospect of civil war or mass starvation.

I’m not as confident as you that this kind of groundlessness is generative, or necessary. To take these mixed metaphors even further — it’s difficult to chart a subversive pathway to an undercommon life if the ground just above us is fracturing, if the school basements are all locked, the water coolers removed, if the food banks and kitchen pantries start to run empty, if digital screens have atrophied our ability to look each other in the eye, if social media has taught our younger siblings that the only form of political engagement is critique and banishment.

I apologize for the bleakness, because some days I absolutely share your optimism about the opportunities of the present, but other days it feels difficult to muster.

MB: No need to apologize for the bleakness; bleakness can often be a sober and clear-sighted assessment of the terrain before us. Believe me, there are plenty of moments in which bleakness and even nihilism wrack my very being. I just think my optimism stems from a place of always being able to maneuver within the turmoil, from a sense of knowing — however small (and sometimes it is vanishingly small) — that even purported tyranny or oppressive totality is not all-encompassing. In short, my optimism comes from a deeply Sisyphean place: though Sisyphus was condemned by the gods to spend eternity rolling the boulder up the hill, straining along the way, only for it to roll back down and for the cycle to repeat, even the gods could not dictate what Sisyphus thought on the descent; they could not control or limn what he dreamed as he descended, what he thought, what kind of schemes he continued to cook up (he was still, after all, the trickster they hated in the first place). We may not be able to open our windows or have friends on our porch or drink from water fountains anymore. And that is devastating for many. Nevertheless, we laugh on Zoom, we mask up and walk to our grandparents’ house just to say “hi,” we read the book we've been meaning to read, we find out we're not as introverted as were thought and in fact reach out to more friends, we are distracted in different ways that now allow us to see different things about the world, and we protest still. And that is why, like Sisyphus, I imagine myself and others happy.

IW: As forewarned, I already feel different, a bit better.

So far we have mostly focused on the “anarcho-” in anarcho-Blackness, but I’d like to shift a bit to talk about how you conceive of Blackness more generally and how the recent uprisings and demonstrations have confused the American racial caste system. Summarizing a remark by Ashanti Alston, you write in your book that “Blackness does not merely consolidate all those who meet a racial quantum. Such a measure would collapse and monolithize those under its rubric.” And later, citing an exchange with Fred Moten, that Blackness “must be claimed by any and every body.”

These conceptions of Blackness — as something both radically open and fundamentally impure — is one that would probably confuse (and maybe even terrify) many academics and activist-types who have invested so much into static conceptions of Blackness as a marker of racial identity. Could you explain a bit about why you’ve thrown yourself behind this more un-settled understanding of Blackness?

MB: I get in sooo much trouble with this understanding of Blackness. And I get it: it is often understood, and deeply felt, as something exclusive, something provincial, something only a few of us get to have. That to me, however, is blackness as affixed to a racialized category. There is another way I understand Blackness though, a way that is different and distinct from that racialized category. This distinction is what Fred Moten and Nahum Chandler and J. Kameron Carter would call “paraontological.” All that means is that, as Zora Neale Hurston has said, “all your skinfolk ain’t kinfolk.”

So this is to say, Blackness as linked to the skin is not sufficient for me as a referent for how one does a certain kind of work, a subversive and oppositional and transgressive work. I am interested in politics broadly conceived rather than doubling down on a racial identification, which is not unimportant, surely, but ultimately insufficient for the radical, insurrectionary, abolitionist work I am in service of. Blackness then comes to index the very subversive force that cannot be hemmed by taxonomic logics, racial classification among them.

To put a finer point on this, it might be best to defer to three thinkers. The first is Hortense Spillers, who writes in the introduction of her essay collection, in a reading of Ralph Ellison, “‘Blackness’[:] a symbolic program of philosophical ‘disobedience’ (a systematic skepticism and refusal) that would make the former available to anyone, or more pointedly, any posture, that was willing to take on the formidable task of thinking as a willful act of imagination and invention.”

The second and third are George Shulman and Fred Moten. In his essay “Fred Moten’s Refusals and Consents: The Politics of Fugitivity,” Shulman writes,

As the name for life’s animating and undoing excess, blackness provokes forms of order...Blackness thus connotes aspects of life that anyone can – and all need to – acknowledge. Moten thereby conceives the life made by those marked black in terms neither ethnically closed nor symbolically foreclosed, but politically and aesthetically open.”

Shulman continues in a footnote, “Indeed, blackness is ‘before the binary said to define our existence’ and ‘older than Africa’...[B]lackness is a general force of fugitivity that racialization in general, and the more specific instantiation of the color line, exacerbate and focus without originating’.” He thus denies that blackness is a “property” that belongs to Blacks.

IW: This idea of blackness existing “before the binary” — that is, before the racialized demarcation of African slaves/indentured servants that occurred in 17th century Barbados and then later in the mainland colonies — is a really useful way of elaborating this other non-epidermal understanding of the term. Without that kind of clear distinction, I imagine that many people might mistake this commitment to openness as an invitation to a sort of “transracialism,” which apparently is back in the news again.

Instead, what you and these other thinkers seem to be positing is that this other kind of blackness is actually impossible to appropriate, because by its fugitive nature it could never truly be owned in the first place. In your book, you instead strive for “holding in a way that does not commit to having, to ownership,” and “to [living] without being owned and without owning; a way to have done with properties and the private without giving up sensibilities of holding.”

This deep commitment to fugitivity and openness seemed to be on full display in the un-managed demonstrations and riots back in late May. Before the black middle class counter-insurgency could take root, there was a common sensibility within these crowds that everyone who was present deserved to be there, that everyone had a duty to protect one another, and deserved to savor the victory over the police. Numerous videos from Minneapolis show Somali women throwing back tear gas while Black and white high schoolers from the surrounding neighborhoods proudly posed in front of the burning precinct together. Judging from the hundreds of mugshots and self-incriminating (but still heartening) tweets, this generalized rejection of whiteness and embrace of Blackness was seemingly pervasive throughout dozens of urban areas for a few weeks’ time. With several months of hindsight, what do you make of this sudden and surprisingly diverse insurrection? And what about the more recent and persistent unrest in majority-white cities like Portland and Seattle?

MB: Yes, it is much more gritty, as it were, than a shallow “transracialism.” It is a necessary commitment to do insurrectionist work, to be in the trenches — living and loving in the trenches, as Audre Lorde has said — and on those grounds there is an affiliation and coalition, the grounds of insurrection and insurgency, or political and politicized work.

The sudden rise in more diverse insurrections out in the streets is deeply heartening to me. Not heartening in this, frankly, bullshit notion of “diverse communities coming together” but in what seems to be a demonstration of the commitment to the fact that the terrors of capitalism and cis white masculine supremacy accost us all, in varying degrees, but all of us nonetheless. It manifests a genuine belief in the coalition: that the harm being done to Black people, for example, is harm done to those in the struggle and in solidarity with Black people and blackness. It is a demonstration, I think, of white folks’ refusal of whiteness, their refusal to allow whiteness to ensnare them into its folds. Uprisings happening in majority-white places, to many, and to me as well sometimes, seems like it might surely be the result of a certain kind of fear: white folks thinking that “I better say that I support Black people and BLM lest I get canceled or called, gasp, a racist.” But I want to think that it is more than that; I want to think that all the houses with “Black Lives Matter” signs on their lawns and in their windows in Evanston, IL — where my university rests and through which I drive weekly — might, as it were, infect those white folks. It might have the unexpected outcome of forging them, incipiently, slowly and gradually radically, through a kind of Black radicality. And I'm all for that. Blackness and its radicality, insurrection and insurgency, have more than enough room for everybody. So get in on it.

IW: I want to think it's more than that too. Surely some white people are motivated by that fear you mention of seeming socially progressive — but I find it hard to imagine that this fear was the exclusive or even primary driver of white participation “in the trenches” as you put it. Putting up a yard sign or even attending a few protests doesn't compare to the stakes of actively participating in the street battles with police, or setting fire to state and capitalist property. In their recent letter to Liaisons about race treason in the George Floyd rebellion, Nevada declared flat out that “no one sets fire to a police station out of shame.” I think we can read this refusal of whiteness as a form of, or perhaps a symptom of, this process of desedimentation you spoke of previously, which I want to return to briefly.

Thinking about fragmentation seemed to have a certain resonance during the Trump years and especially with last year's confluence of pandemic, uprising, and election. When we began this interview last autumn, it seemed like everyone was clamoring about an upcoming civil war. A year later, it feels as if things have settled again. Following January 6th and Biden taking power, the state has been hard at work attempting to reimpose itself as a unified totality. How have the last several months changed your thinking on this fragmentation and groundlessness?

MB: What an astounding question. I think the last several months have done a number of things to my thinking and feeling, from a number of avenues.

On the one hand, things have “settled” and there is no longer the governmental, bipartisan, presidential "face" of the terrors of the nation for us to use as a foil to mark and tout ourselves as “not like that.” In other words, it was quite easy for many of us to understand ourselves as sufficiently “radical” when we had “45” as a comparison. Now that Biden is in office, with his moderateness and tepid liberalism, it is easier to feel comfortable. This is, as I'm understanding it, we’re witnessing a resedimentation, a return to the settled silt of a “moderate and sensible,” which is to say, non-radical politics. And that is disheartening.

On another hand, as I describe in my forthcoming book, Black Trans Feminism, I am unceasingly hopeful, fugitively so. That is, I refuse to believe that those white folks or those cis folks or any of those hopelessly normative-identificatory folks who began experiencing tremors in the austerity of (their) whiteness and cisness and identificatory normativity just disappeared. They are still there, thinking and feeling and experiencing the subtle and not-so-subtle tugs of radicality. In other words, they cannot fully put themselves back together after having been fractured. The fracture, like broken glass, will never be recomposed in the exact same way. They are still out there, doing something, perhaps less visible, but I am of the belief that they didn't simply “go back to normal.” How could they? So it seems to me that even though the ground has in many ways re-congealed, at the very least, it has not congealed in the same way, and that difference is consequential. That difference means that something else, something new is now possible that was not before, and I find that generative and hopeful.

(And we still, with this, continue to agitate and write and think and commune along the lines of radicality, never letting these people remain comfortable. In other words, this ought not to make us complacent but all the more vigilant — we have seen a glimmer of what we might become, and we cannot simply “go back.”)

Additionally, I want to note the ways that the past several months, the past year, has affected me personally. Some are aware of the online accusations against me regarding harm that I’ve done, and that bears upon my thinking and relating as well. Even those of us who aspire toward and try to enact as much as we can radical politics do harm — serious harm — to others. We all do harm, differently impactful and non-equivalent, but harm nonetheless. And we are responsible for those harms. When the claims were brought to me, I was faced with a decision: do I try to tell “my side” of the story and perpetuate this long history of continued violence that takes gendered form as a “he said/she said” (though I am not a “he,” and am acutely aware of how queer and nonbinary people like myself have their sexualities demonized, often retroactively)? No, I did not want to do that, and refused to. The breach of an ethical relation necessitated that I show up, now, in an ethical way, which took the form of steadfastly doing things that, now, try to mitigate harm — foregoing royalties for the Anarcho-Blackness book (which are being given to an organization committed to ending gendered harm), going through a multi-tiered accountability process, opening myself up to the gloriously terrifying process of transformative justice, and doing all of this willingly, non-begrudgingly. In short, I was fractured and fragmented, my sense of self was fractured and fragmented, so I needed to heed that and not try to simply “go back.” I needed to, and continue to need to, mend and heal and grow and transform. The ethical call I was faced with, in the notation of the harm I had done, was to take that seriously: how can I be accountable? Go through an accountability process to the extent that the person harmed wished; do that process openly and honestly; be and continue to become transformed by that process, impacting not just how I interact with a handful of people but with everyone (I even had an open conversation with my students after a few of them heard about the accusations, and that conversation was hard but so, so important).

To cry in front of others and have them witness my sitting with the harm I did, to continue to commit to abolitionist politics in the face of others who might want me carcerally punished, or to demonstrate kindness and compassion to all — that pervades how I, we, must live in the world. So often many do not wish to be accountable to their harms because — and I count myself in this too — there is a fear that they will be disposed of or exiled. But abolition necessitates that no one is disposable. No one, full stop. We are to hold and love and care for everyone, even when it is hard, and I want to commit to that. Because that to me is what radicality looks like. In holding accountable, there is double emphasis on the accountable and the holding.

So all of this is to say, there is a fragmentation of even our logics of relationality. When we see the 45th president shunning or disposing of or maligning others, or accused of harm he's done, how do we respond with respect to abolitionist politics? We are to fracture that impulse to incarcerate and dispose, desediment the commonsense-ness of immediate shunning. Ask: what are the conditions that made this harm possible? How can those harmed be facilitated in their healing? (And if the facilitation during my accountability process is any indication of how it could be for others, we would be in a monumentally different world if we were all shepherded and held in that way, my god). How can we ensure that harm is mitigated, because even those who do harm have been harmed and need, too, care and compassion. How do we commit to the axiom that, as adrienne maree brown concisely put it, we will not cancel us?

That is one of the ways, I think, ongoing desedimentation of carceral impulses can look.

IW: I really appreciate you sharing that experience with us. In a somewhat oblique way, it ties in with my next question, on gender. In your work, the theorization of blackness always seems to go hand in hand with the theorization of gender, of transness. If I'm reading you correctly, you seem to rebuff what has become a commonplace ideology of “intersectionality.” For example, in The Problem of the Negro as a Problem for Gender, you write that, “I do not simply mean that black 'women' are 'multiply marginalized' but something more incisive: that the figure of the Negro, that blackness, animates and instrumentalizes gender always toward its dissolution.”

This reminds me of a claim Idris Robinson makes in “How It Might Should Be Done,” one of the most groundbreaking interventions from last summer's rebellion, where he states that intersectionality is “no longer feasible or viable as a guide for us. [...] In place of intersectionality as a discourse of systemic oppression, what we need to do is to bring back the idea of Black feminism as a discourse of struggle.” It seems clear that it’s necessary to think beyond a simple matrix of identities defined by their oppression, compounding on each other, and that is what you are trying to develop through your upcoming work. Can you elaborate on what this more incisive thought looks like for you?

MB: Absolutely. I was actually on a panel with Idris Robinson when he said something very similar and I was floored. Like, “There are other people who are thinking this way?!” That was wild to me, and so heartening. So I love that Idris is promoting such a stance.

So yes, Black Trans Feminism is trying to do just that: to think in excess of intersectionality, and indeed, “identity” as such. To me, identity is not an innocent description; identity is a regime, a normative regime at that. I want to radically reconfigure what “identity” means, and this desire is motivated by an understanding of identity as resting on an assumptive coherence, knowability, and nonporousness, all of which are regulated, normative regimes of legibility and stability. This disallows so much that we might be or could have been. Which is one of the reasons why I mobilize, in all realms, abolition: it is because various identities — race, gender, sexuality, etc. — all foreclose what we might have been but for these notions of race, gender, and sexuality. In other words, it is not that one simply is a certain race or gender; those things are impositions, “imposed ontologies,” as Fred Moten would say, and as such they circumscribe us ontologically from the jump. We are not permitted to appear or exist without them; who we could have been is already, from the outset, curtailed. On this, I draw on Judith Butler’s Frames of War:

Mobilizing alliances do not necessarily form between established and recognizable subjects, and neither do they depend on the brokering of identitarian claims... [W]hen such networks form the basis of political coalitions, they are bound together less by matters of 'identity' or commonly accepted terms of recognition than by forms of political opposition to certain state and other regulatory policies that effect exclusions, abjections, partially or fully suspended citizenship, subordination, debasement, and the like.

So I care much less about one’s identity, not because it doesn’t matter at all or isn’t relevant; rather, I care less about one’s identity because that says little to me about how a person feels and what they think about how they move, or do not move, through the world; it says little to me about their relationship to white supremacy and cisnormativity and heteropatriarchy, or about what and how they agitate for, how they subvert and disrupt power. I’m interested in politics and dispositions and postures: not “Are you Black?” or “Are you a Black woman?” or “Are you transgender?” but instead how do you do blackness? How do you engage black feminism? How do you promote trans insurrection?, where all of these things are modes of analytic critique and subversive of power. They are, in short, things that we do, not, simply, things that we are.

“What do your politics look like? What kind of work do you do?”, as my dear friend and homie Marshall Green has written. (They have also said on a number of occasions, taking seriously transformative justice and abolition, “People do monstrous things, but no one is a monster.”)

If abolition is about a whole host of things — non-disposability, eradicating not simply violence and carcerality but the possibility of a world where violence and carcerality make sense, departing from normativity, imagining otherwise ways of doing and being and living, care and compassion and love — then part of this must include owing it to ourselves to dare to imagine something wholly different. We cannot hold onto the things of this world, particularly those things that make us comfortable. Again, as I write in Black Trans Feminism (and forgive this lengthy quote, but I stand by each word):

[I]dentities are at base hegemonic bestowals and will thus have diminished liberatory import in the final analysis; indeed, we cannot get to the final analysis — which I offer as an abolitionist analysis — with these identities if such an abolitionist terrain is given definition by way of the instantiation of the impossibility of violence and captivity. Black trans feminism cannot abide such classificatory violences, so it urges us to also abolish the categories we may love, even if they have not always been received well. If the aim of the radical project of black trans feminism is abolition and gender radicality...it is imperative to grapple with what that actually means. We cannot half-ass abolition, holding on to some of the things we didn't think we would be called to task for giving up. If we want freedom, we need to free ourselves, too, of the things with which we capture ourselves. The project at hand is interested in a thoroughgoing conception of freeness, and it seems like black trans feminism, to call on Saidiya Hartman, ‘makes everyone freer than they actually want to be.’ When the white woman or the black trans person or the queer-identified person comes at such a project with their indignation about me, us, black trans feminism, trying to take away the very things that we’ve worked so hard to achieve, we are surely to meet them with a certain level of kindness as an ethical attentiveness to how such trauma has been felt and the joys of mitigating, in whatever way, those traumas. But, and I mean this, we are not to capitulate to a sort-of abolished world because some people who may look like us or the people who have been forged in oppression are pleading to us. We still, even when Grandma doesn't (think she) want(s) it, work to abolish the world. That is what black trans feminism, as an orientation toward radical freedom, commits to. And that will not be easy, nor will it feel good in the ways we expect.

So I want us all to dare to imagine and insist on a world that even we cannot fathom. That will look utterly outside of our very framework for encountering the world. And I smile at such a fact, because then we might actually, finally, be able to live.

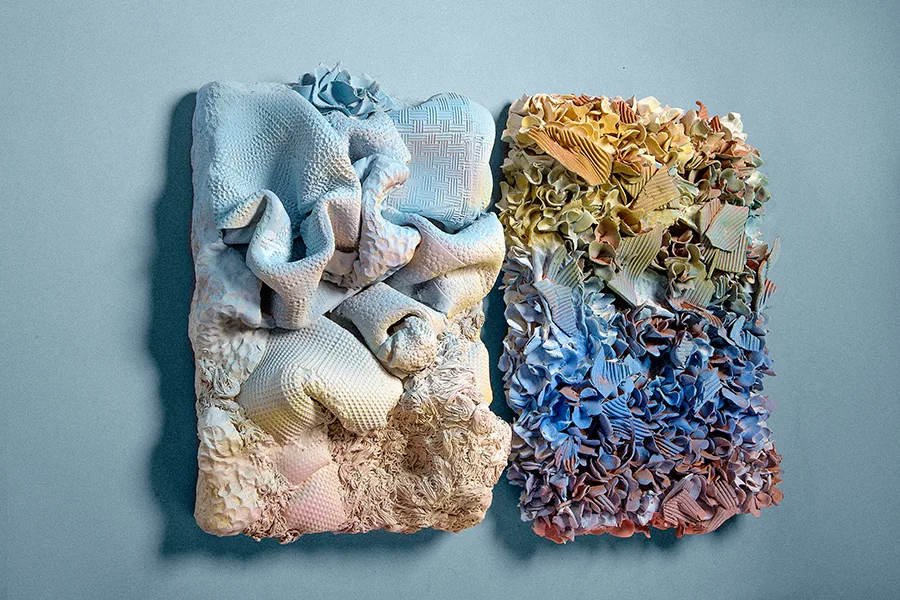

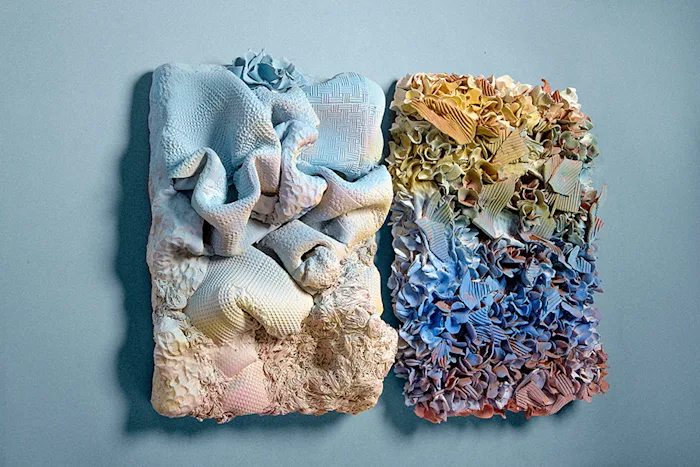

Images: Morel Doucet