Athena, or Logical Revolt

Maxence Klein

Other languages: Français

The release of Athena, the latest film of Romain Gavras, has set off many impassioned polemics in the press and on social media. The following text starts from a simple observation: if this film is so troubling on the left as well as the right, this is because it doesn’t aim to produce a political discourse, but it shows all the violence and confusion of what the first stages of uprisings in the 21st century might resemble, given the current state of the forces involved.

The main object of Romain Gavras’ new film is to confront us with a tangle of problems that are both ancient and painfully current. In our distant past, when the yoke of injustice fell upon a community, things were always simple. First there was anger: voiceless, inexpressible, looking for an outlet. In rare instances, from this anger — almost always unarticulated — there emerged a violent revolt.

An insurrection doesn’t always need a grand chorus of words. However, while anger in its purest form is a prerequisite to any serious revolt, unfortunately it is also always subject to complications. How then does one revolt? This is the central question that Romain Gavras asks with Athena, one which allows him almost miraculously to escape the fate of the bad left-wing film on the "banlieues question.” This rhetoric has been a well-known lamento in the French political sphere for well near 40 years, and it testifies to the complete inoperativity of the national myth of socio-economic and cultural integration.

From the revolt of the banlieues in 2005 to the Villiers le Bel uprising in 2007, by way of the riot for Théo provoked by the Bobigny court proceedings in 2017 — and of course, without going into the struggle of all the families plunged into mourning by unpunished police murders — the question of police brutality, but also more generally that of the segregation of working-class zones and the structural racism endured by their inhabitants, are symptoms of the decay of the Fordist compromise and the French welfare state, of a colonizing past that refuses to pass into history, but above all of the selfish radicalization of the political, economic, and cultural elites.

It’s in the context of this Gordian knot of the French political scene that Athena stages a fratricidal tragedy at the heart of a broader drama, that of a collective revolt approaching its maximum potential. A rare-enough event in French cinema, Athena is the filmed account of an insurrection, that of a neighborhood reacting to the death of one of its children, killed by the police.

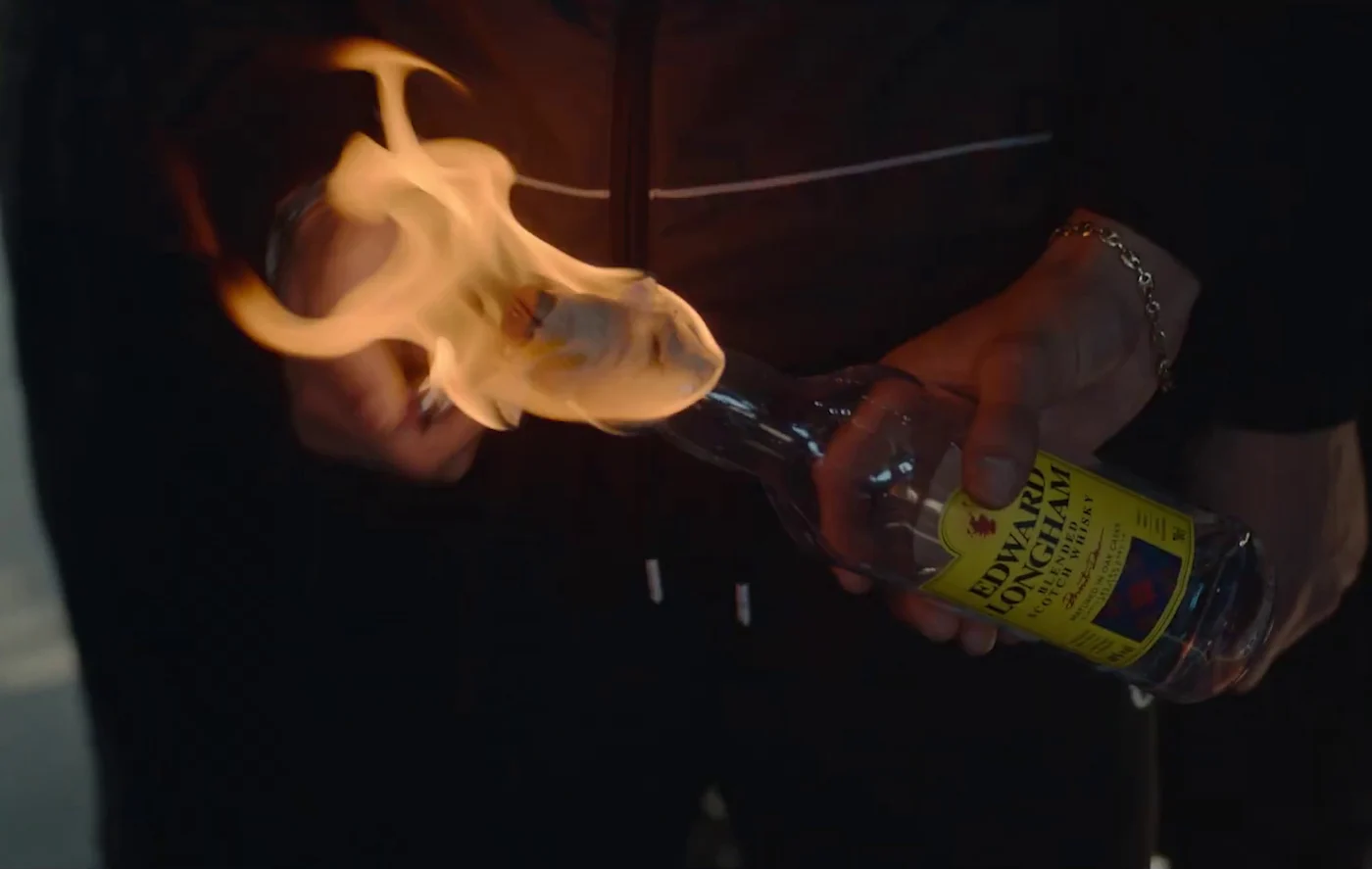

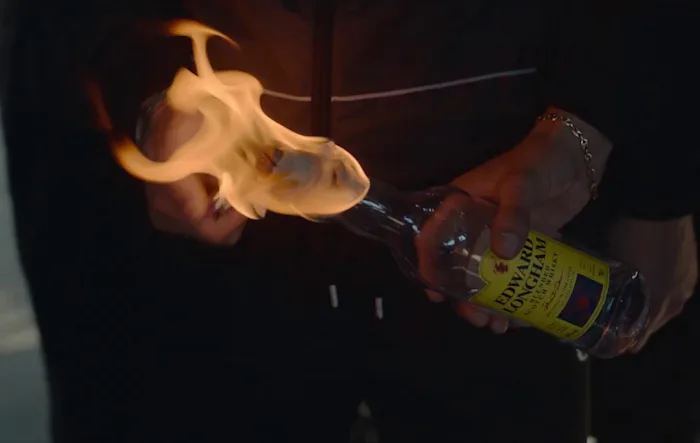

The film opens with a long take capturing a rage that will be exhilarating to anyone who’s taken part in the beginnings of a collective revolt. Starkly framed, it shows young men who, proud in their mourning and tired of being victims, decide to organize to attack a police station, grab what they can, including weapons, and quickly repair to the hood. It’s after these happenings that a cycle of revenge is set in motion; as night falls, the balance of power sinks in and one is reminded that a true tragedy always begins at dusk – at the twilight of a civilization.

1.

What was tragic drama for the Greeks and how does Romain Gavras recast its distinctive elements for us? The historian Jean-Pierre Vernant has shown how, for the Greeks, tragedy was an eminently contentious genre in which “the city becomes a theater and performs its own roles in front of the public.” This tragic theater is an art that denounces pell-mell the ambiguities of subjectivity, communication, language, ideas, institutions, and the very cosmic order. To carry this off, the tragic genre invents at the same time a new use of the myths that preside over the city by actualizing the recurrent problems that men and women may come to face in their own life. Whereas myth presents ideal behaviors or abstract models for human action, here the mythic hero disappears, he or she ceases to be a model to instead become a problem, appearing to the spectator as a knot of divided antinomies.

It’s no use looking for any prophetic meaning in tragedy, because it doesn’t in any way constitute a window on the future. Nor is there any catechism in tragedy. Moreover, the tragic genre doesn’t engage in political deliberation. It doesn’t really participate in civic life. For that, the Greeks invented a very different theater, namely, that of political representation, with its art of rhetoric and its procession of certified liars, power freaks, manipulators, and narcissistic perverts.

Whether it deals with love, lineage, revenge, war, or peace, Greek tragedy doesn’t teach anything. As a genre, it primarily seeks to magnify the meaning of concrete problems through the use of symbols. In this sense, Athena presents three brothers as three ethical possibilities for grappling with the problem of reparation: Abdel still believes in the justice of this world, whereas Karim means to avenge himself whatever the cost, and Mokhtar is prepared to do anything that will save his business. These tragic characters present fragmented personalities who are confronting a cosmic, ethical, and governmental order: that of an undifferentiated violence that falls upon young French banlieue dwellers. From their impossible mourning and the intimate sufferings of this symbolic brotherhood, there will emerge a rage that is impossible to channel and whose successive overflows will first infect their neighborhood and then, off-screen, all of France.

Athena is primarily an amoral film that doesn’t seek to teach a lesson, explain something, or communicate some political message. With a remarkable seriousness, its aim is to raise the problem of the practicability of revolt in the 21st century based on a specific case. Those who look to films to find answers are bound to be disappointed, for one would have to be a poor film viewer at best, or a stupid one at worst, to ask cinema to offer readymade solutions to the unresolved problems of justice, equality, and human freedom. On the other hand, those who remain on the lookout for the means to breach the walls of our epoch will be drawn to reflect more than once on the scenes and implications of a film like Athena.

By showing what is beautiful and what is ugly in a necessary insurrection, the film intends to challenge the viewer and his little frozen conclusions. To the good conscience of the left, it says something like, “You who have abandoned us, with your presumed great universal mission, your false promises, and your cronyism, look at the radicality of indecipherable anger that inhabits us.” To the rightist bad conscience and its resentment, the film spits out a big fuck you: “You should shut your face. If someone killed your little brother, you would take your revenge; in fact, you have spoken of nothing other than revenge for years. We’re the police now, we’re the real state of exception.”

Although the story is situated locally in a peripheral and segregated area of the Parisian metropole, in their respective torments as well as in the violence of their martyrdom the situation of the protagonists acquires a universal status that echoes all the contemporary uprisings. From Hong Kong to Chile, from Sri Lanka to Iran, from the France of the Yellow Vests to the insurrection that responded to the murder of George Floyd, a list now too long to be exhaustive.

2.

Barbarism is an invention of the Greek polis. Yet the latter was never the only model of political organization in the peninsula. Perhaps the polis was never even the majority model. In this regard, the historian Pierre Cabanes has shown how, among the Greeks, the model of the city-state, the polis, was commonly set against that of the tribe, the ethnos. The city-state was born into a world in which natural resources were to be fully exploited, a “full world” whose political organization sought to maximize the use of the available resources. At the same time, this full world was configured as a closed world, with its community of citizens shut off to those who didn’t belong to it, a specific territory to be governed plus neighbors to be conquered. A community, then, that defined itself against its alterity and enclosed itself within its lands, the chora, but also within its cults and its social model. These sanctuaries formed its boundaries. This little world was not only closed to its outside, to the foreign, but was also internally closed, in that it did not grant the same rights to all the inhabitants of the civil territory but only to a part of them, the citizens. All the others, the women, the slaves, the foreigners were excluded.

Opposite the world of the polis stood that of the ethnos. A world of free and differentiated communities that appears very different in its conception of the political. Its collective organization sets itself against the idea of a closure and against the fencing-off of a territory. Most often the ethnos corresponds to a pastoral model that geographically needs space for organizing its seasonal pastoral migrations from a plains area where the herds or flocks spend the winter to the mountainous areas reserved for summer pasturage. This conception of the group requires, therefore, a specific diplomacy in order to ensure the seasonal migratory itinerary. Its geography is open, as is its attitude towards its neighbors. The open model of the ethnos stands radically opposed to the isolated polis, so much so that Pierre Cabanes even wonders whether the notion of polis didn’t actually come out of the common fear of overpopulation and the urge to enclose the community into itself. At this point in time, it might be precisely these sorts of open worlds that could oppose the final enclosure of the world of capital and its endless train of supernumeraries.

3.

In many cosmogonies, fratricide lies at the center of the creation of an order or a world. Mythic fraternal relations commonly present two brothers gripped by a radical adversity embodying rival conceptions of the world. The hostility that pits Cain, the sedentary farmer, against his brother Abel, the nomadic shepherd, offers a retrospective angle on the questions and problems that may have occupied Hebrews who were pondering their nascent political and social organizations.

In its duality, or in its triad as in the film, the motif of enemy brothers tends inevitably to suggest a unity in opposition. Dramatically, Cain and Abel represent a founding paradox: the necessity of a rational choice for humans presented with the possibility of collectively establishing a certain type of civilization. If they fail to live together, this is a way of impressing upon us that a truly just world, a materially repaired world would place at its heart an ethics of alterity. More particularly, in Athena, this fratricidal opposition takes form starting from a moment of exception in the established order of the city: the police killing of the youngest of the brothers produces a vacuum in the everyday order once the police are chased away from Athena’s sacred environs. A form of state of exception reinforced by the strange absence of the figure of the father and the rapid effacement of that of the mother who is quickly evacuated from the scene of the drama. In their martyrology, the three brothers are seemingly at the event horizon of one world being swallowed up and another struggling to emerge. In this sense, the self-destructive apotheosis represented by the explosion of their building, but also the triumph of the crassest police brutality, signals the impossible transition from the state of retributive justice to that of restorative justice.

The extraordinary thing is that, with its insurrectional phantasmagoria, Athena dares to show us the dramatic limits that contemporary revolts continue to encounter at the present juncture. The film reminds us of something obvious that many seem nevertheless to have set aside out of cowardice and petty compromises: the road that leads from a general state of injustice to a reign of equality will never not be dangerous. Here the unities of time, place, and narrative progression that characterize the tragic genre form a framework in which founding violence cannot be staged, and even remains opaque to the tragedy’s participants themselves. The violence borders on a mythical dimension of the human psyche which, being the orphan of a larger movement of self-emancipation, has also lost its sense of the history of the oppressed as a continuum. Athena is a revolutionary film which paradoxically doesn’t say anything about revolution. The film painfully shows the viewers that in the current state of the forces in presence, a revolution remains impossible, despite the fact that the motif of revolt is clearly among the commonly shared assumptions of our epoch.

Thus, there is little doubt that the insurgents are relying on the repertoire of collective action that has emerged starting with the riots of 2005, and updated with successive eruptions. In their revolt, the characters are anything but ahistorical beings and their style draws from the archetypes of revolt. In this way, the attack on the police precinct reactivates the memory of the storming of the Bastille, but also the people’s seizure of Paris’s cannons, the main triggering element of the Commune in 1871. Similarly, the oath to protect the city and the allegiance of other districts to the revolt recall the revolutionary oath of the Jeu de Paume in 1789. What differs drastically from past insurrections, on the other hand, is that the film’s protagonists are tragically deprived of a tangible revolutionary horizon.

4.

The neoliberals shed their nostalgia for a golden age a long time ago and it is high time for their adversaries (on the left) to follow suit, failing which they will have definitively lost without even doing battle. With a certain degree of admiration, we must concede that the neoliberal intellectuals have fought harder to achieve a deeper understanding of the political and organizational character of modern knowledge and science than their left-wing adversaries, and consequently they represent a contemporary challenge worthy of the name to all those interested in the archaeology of knowledge. From a different perspective, however, revolution with its inevitable character of bifurcation needs to raise itself to the level of a new science of humankind.

Early signs of secession are stuttering everywhere in the world, without succeeding, for the moment, in piercing the desert of the real. It is also because the order of the world has been confiscated by those citizens of the metropole who don’t feel concerned in the least: that managerial class of decadents who selfishly enjoy their super-salaries and are determined to defend the turf offered them by the propulsive force of value, and hence a complete lack of values, that automatic excitement of the Last Man that grows in the muck of a holy communion of absence from the world, from oneself, and from others. The powers that we revolutionaries are confronted with are spiritually zeroed out. It’s just that fighting zombies is no easier a task than squaring up against living adversaries.

In this sense, the paradox of a film like Athena is that it documents an insurrection without being a political film in the classic sense of the term. Because politics, its myth of representation, and its old theme of dialogue, have been destituted by the dictatorship of the economy. In his Politics at Dusk, Mario Tronti proposed reading the crisis of governmentality affecting today’s democracies as a consequence of the defeat of the workers’ movement. The capitalist class and its minions no longer need to mobilize politics in the same manner as when a group as massive as the working class positioned itself as a counter-model. With the defeat of the workers’ movement in the last third of the 20th century, the question of government has been replaced by that of management. Classical politics was not destituted by the revolutionary waves of the 1960s and 1970s but by the economic restructuration that directly followed them.

The utility of a film like Athena lies in the way it exhibits and demonstrates to all the mandarins of the Empire of the economy who until recently were still gurgling about the end of politics that it has now returned, only in a reversed and hence much more dangerous form. The past decade has seen the emergence of a global anti-politics, fragmentary in its forms, chaotic in its demands, contradictory in its formulations, but above all ungovernable and unco-optable by the custodians of the existing ideological order. If every civilization feels the need to raise its minoritarian otherness to the stature of barbarians, our epoch is completely saturated with the kind of relegation invented by the Greeks. But this saturation also reveals something: as the journal Endnotes has recently pointed out, these barbarians have yet to pronounce their last word. For those still able to pay attention, the recent wave of uprisings reminds with every passing month where contemporary class struggle resides.

5.

Utopia now seems to have gone over to the side of capital. It is capital that attempts to secure its dominion over everything that lives, and whose ideological ambassadors speak to us of conquering other planets and even of abolishing death. For us revolutionaries, this situation offers us a rare piece of good fortune: everything we need is already there. Utopia is the expression of a blocked temporality that invents a fake sense of time as a form of imaginary compensation.

Yet, confronted with the apocalyptic character of our epoch, it’s as if only two solutions were on offer to the camp of justice and equality: either to redirect politics against the economy, the so-called “realistic” solution, or else exodus and the great bifurcation, the so-called “utopian” solution. However, such a binary vision of the world rests on a false dichotomy, since it merely re-enacts the story of that infernal couple of 20th century political history: “reform” and “revolution.” We would do well not to repeat this error in the 21st century. Any form of revolutionary upsurge will necessarily have to include the invention of new political geographies beyond the false oppositions inherited from the history of the 20th century.

6.

On the left, we often like to blame the people. They’re supposedly not up to the challenges of the day. However, the events of the past few years have revealed the so-called inaction of the masses to be a mirage. Still, if there is something like an irreducible blockage, we maintain that the real revolutionary work will begin by giving people reasons to hope, despite the high degree of instability of the global economic and environmental situation. We would even say that revolutionaries need to devote part of their energies to producing some tangible rational hope and to equipping themselves collectively with achievable objectives.

On the planetary scale, it appears that a gigantic process of generalized proletarianization is in the process of being translated into an unprecedented cognitive uniformization, but also by an unparalleled loss of the knowledge and techniques that the human community managed to acquire over thousands of years. A vanguard of the cybernetic economy dreams of a completely calculable world and intends to bring about the anthropomorphosis of capital by creating from scratch a society of generalized calculability. Here we are, then, having arrived at a kind of eschatological moment of the Anthropocene: either we are able to reinvent forms of knowledge, or we’re finished.

7.

Revolts are always logical. Each of them has its own rationality and a mysterious dramaturgy at the same time. A friend of mine remarked that in this sense, the strength of Athena lies in the way it combats the idea that the participants, who have a narrow and compartmentalized experience of the horizon of their actions, are not still capable of making history and of generating effects extending far beyond their local arena. It’s as if the film’s protagonists were always operating in an asymmetry with the rest of the situation that surrounds them. The interest of the film is owing to its determination to give these young men the possibility of being historical agents, while also uncompromisingly debating their nearly total inability to accept their vocation as a revolutionary vanguard and their lack of preparation for such a task. In a way, it’s as if the film were a meditation on the possibility of an uprising deprived of revolutionary subjects or, to say it in the words of the sociologist Asef Bayat, an uprising of revolutionaries without a revolution.

In this sense, Athena is first and foremost a film about late capitalism’s reign of separation. It depicts a proletariat mangled and fragmented through marginalization, trying with difficulty to survive in a world split apart by a civilizational crisis. Individualities clash in an embryonic civil war. Any dialogue is made impossible by the multiplication of the contradictory interests of the protagonists. While the ideal of republican justice and traditional Muslim ethics are overwhelmed by the fury of the events, the rioters make a rational, albeit suicidal, wager on a physical face-off with the authorities. As for the near-absence of women during the whole film, it underscores, in a negative way, the impossibility for these young men of projecting any sort of counter-society. But is that even their goal?

The events staged in the film reveal that the world we live in is characterized by two superficially contradictory but deeply interconnected aspects. Our lives are ruled simultaneously by a radical governmental order and an extreme economic disorder. In France, Macronism, with its personal vision of power and its eco-technocratic policies, advances by destroying what is left of the social equilibria issuing from the Fordist compromise of the thirty-year post-war boom. Off-screen, the film shows how a disciplined army progresses in a field of ruins, it shows an economic order advancing through the chaos it engenders. But is that really the end of the story, history’s last word?

First published in Quartier Général, September 29 2022

Translated by Robert Hurley