bell hooks and Wayward Immobility

Meredith Lee

Are we capable of enacting a reading practice that embraces individuals who ‘misbehave,’ even under conditions of relative freedom? —Kaiama Glover

On December 3rd, 2021, my wife (Judy) and I drove down to Berea, Kentucky to visit bell hooks and bring her books.1 At the start of the pandemic, I somehow became bell’s book buyer and would always bring a few bags of mysteries — primarily cozies — when seeing her. bell and I spoke on the phone many times a week, usually just to check in and talk about our daily lives. She hadn’t been answering the phone so I was concerned (bell would correct me for using the word “worried”) and wanted to see her in person. When we arrived at her house, we found her in critical condition and urged her to get emergency medical care, but as usual, she denied it (she always rejected the medical industrial complex and its relationship to antiblackness), desiring that her friends and family care for her instead in the form of mutual aid — a nod to Dean Spade, Mia Mingus, and others. And so, we cared for bell because we love(d) bell, even when she misbehaved.

After leaving Berea on December 5th, bell became even more sick, and Judy and I drove back to Berea on December 7th to help care for her during her transition out of this world. On our way back, we listened to a talk by Kaiama Glover on her book A Regarded Self. After over 10 years of friendship with bell, I have never heard anyone conceptualize the unruliness of Black womanhood in a way that could encompass bell’s very being. A Regarded Self analyzes Black female protagonists’ regard of the self in Caribbean texts such as Maryse Condé’s I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem, René Depestre’s Hadriana in All My Dreams, and Jamaica Kincaid’s The Autobiography of My Mother. Glover writes, “The insistent self-regard of these protagonists draws our attention to the constraints and insufficiencies of what we often presume to be radical or expansive categories. These women remind us that any commitment to inclusivity and justice must make room for wayward subjects.”2 I think this describes bell precisely. She encompassed waywardness, not only through her thorough and specific ways of being (or not being) but through the ways academia envisioned her or failed to envision her. During her New School conversation with Melissa Harris Perry, bell stated that she liked to think of herself as “exacting and precise, rather than difficult.” She was the most complicated, stubborn, and brilliant person I ever met, and I would indeed say she was difficult because of her exacting and precise ways of thinking and loving. bell’s waywardness and audacity to live her own temporal and spatial life provides a way of reading that aligns with Glover’s question in the epigraph. And this way of reading, a reading that encompasses the pain that arises from ethical veraciousness, compelled me to love bell. My own commitment to inclusivity and justice has magnified through knowing and loving bell. Indeed, categories of radical love and acceptance must include many modes of waywardness as a kind of survival that leads to joy in any form.

Yet bell wasn’t exactly wayward in Saidiya Hartman’s terms, who so eloquently writes:

Waywardness is an ongoing exploration of what might be; it is an improvisation with the terms of social existence, when the terms have already been dictated, when there is little room to breathe, when you have been sentenced to a life of servitude, when the house of bondage looms in whatever direction you move. It is the untiring practice of trying to live when you were never meant to survive.3

bell was consistently pushing the boundaries of what might be through her refusal to be anything but unrepentant. Yet towards the end of her life, she was not as interested in what might be as she was about what was here. Her waywardness is one of immobility, one not of survival but of allowing herself to rest — a restful waywardness. Our relationship is a story about restful waywardness; this story that I am writing about bell colludes with Hartman yet figures within the realm of restful possibility, a possibility formed through wayward immobility that gestures back to her work on white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

bell embodied a wayward life through her refusal to accept anything within the bounds of hegemony. To think with Kevin Quashie’s discussion of audacity4, bell had the audacity to not give a fuck what others thought of her. Yet audacity brings much suffering for Black women, especially in the academy. She spoke out against all forms of oppression, even when her opinion was unpopular or regarded as extreme. Like the time she called Beyonce a terrorist.5 bell never stopped critiquing class, more specifically, Black feminist intramural class antagonism and she saw Beyonce as a neoliberal figure who, in her music and visuals, reinforces the very suffering she is attempting to resist. bell got much backlash for that comment (perhaps it should not have been said in front of a primarily white audience at the New School). bell’s misbehavior in this scene no doubt forced Beyoncé to perform at the Grammys with a life-sized lit-up sign screaming “FEMINIST” behind her that same year. bell continued to see racialized gender and class as an intramurally foundational structure of power that was often erased or overlooked when interrogating antiblackness — a term she learned to embrace later in life.

In the last few years of her life, bell rarely left her house. I struggled with accepting this, as we used to go thrifting and go out to restaurants regularly. In fact, I first met bell as a Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies (WGSS) MA student at the Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio in 2010 when bell was there for an academic residency. The WGSS department arranged a lunch for graduate students to meet bell and I happened to sit right next to her (or she sat next to me). I distinctly remember that I ordered steak because bell began to eat steak off my plate with her hands. She asked me why I wasn’t having an alcoholic drink, which I responded that I no longer drink because I’m in recovery. She then outed me by asking loudly “Are you sober?!” bell had always been intrigued by people in recovery and I suspect this aspect of my person explains, at least at first, why she clung on to me for the rest of her visit in Columbus. We spent much time together over the two weeks of her residency as well as the two weeks of her residency the following year. I felt a strong connection to bell and spent the next seven or so years talking to her on the phone regularly and occasionally visiting Berea to see her.

Beginning in 2019, I started teaching at Berea College and living in Lexington, Kentucky and as such, bell and I spent a lot of time together in her home. Judy and I rented a midcentury home on a horse farm where we were surrounded by beautiful creatures: creek otters, farm dogs, our dogs, horses, and white women on horses doing archery, which was totally absurd. bell always wanted to see pictures and would consistently bring up Alice Walker’s Horses Make a Landscape Look More Beautiful. She wanted to visit the farm and see the horses, but she rarely left her house and was afraid of dogs (she would pray about it and would say that she was getting closer to being able to meet our dogs), which always made things difficult because we always have dogs. At this time, I was visiting with bell about three times a week and she would look at pictures of the farm and the horses almost every time.

Although bell returned to Kentucky to be closer to her roots, her notion of home was expansive and complicated. As bell writes:

Indeed the very meaning of ‘home’ changes with experience of decolonization, of radicalization. At times, home is nowhere. At times, one knows only extreme estrangement and alienation. Then home is no longer just one place. It is locations. Home is that place which enables and promotes varied and everchanging perspectives, a place who one discovers new ways of seeing reality, frontiers of difference.6

I lost both of my parents within 2 years of each other during a time when most queer/trans 21–23-year-olds have yet to develop a homespace with their natal parents. It was a time when your trusted kin came from the corner bar or the nearest queer bookstore. As such, my home has always been to be free and be around those that allow me to be free. Not a freedom sutured to a sovereign notion of citizenship or even the freedom ostensibly invoked by radical oppositional movements, but one that allows me to do whatever the fuck I want. bell understood this home that I created and wanted to be part of it, and I wanted to be part of her freedom, too.

Home is nuanced and always changing and both bell and I felt alienation from the notion of home at different points in our lives and connected over this estrangement: “living in childhood without a sense of home, I found a place of sanctuary in ‘theorizing’, in making sense out of what was happening.”7 bell’s was a theorizing compelled by grief and racism/classism while my theorizing centered on grief and transphobia/homophobia. We both felt a strong sense of pride for growing up rurally, even if this upbringing haunted both of us for the rest of our lives. This meeting ground also challenged our need to work, to labor for an academy of which destroys the lives of so many Black women and femmes, as well as queers and trans folks. We felt the loneliness of being outsiders (within) and I connected with her on a deeper level, deepened by witnessing her physically suffer and knowing that she wouldn’t be around for much longer. We allowed ourselves the freedom to suffer and to speak about our suffering. This freedom was very important to bell. To be clear, bell was not my mentor. I like to think we were teaching each other with no pedagogy. We were constantly reaching new levels of honesty with each other. We were an unlikely pairing and we found each other through theory and askance feminisms, through building a home with each other amidst our pain and suffering as well as our joy and our audacity to be free.

But how can you be free when you’ve made yourself housebound? At times, I struggled with bell’s intractable immobility. But as I spent more time with her, which meant sitting with her as she lay on her couch, I recognized that her choice to be sedentary, physically inactive, immobile was itself a form of Black feminist theorizing. I realized that bell was pushing the boundaries of what freedom looks like. As Glover writes, “They [Black female protagonists] call on us to broaden our understandings of what freedom looks like.”8 She spoke a lot about her decision to stop doing public talks and her choice of nonperformance (as Sora Han and Fred Moten put it). Put differently, bell’s act of nonperformance at the end of her life was a radical rupture to what many or most people see as a form of freedom — the freedom of mobility. I taught a Queer and Feminist Disability Studies class at Berea College, and I began to understand bell’s decision to be immobile. bell and I would discuss the readings I assigned as well as the books she read on her own, especially When the Body Says No by Gabor Mate. We analyzed the problems of diagnosis and cure, especially through Eli Clare and johanna hedva, two of my favorites. Further, I recently listened to Therí Pickens describe and theorize the structural conditions within academic institutions that impose and arrange themselves onto the bodies of Black women and femmes and thought about bell and how enamored she would be of Black feminist disability studies.

bell insisted that she never liked to move her body and always preferred staying home to read and write. And then I found this quote on the internet that has no date or reference but is repeatedly cited as being said by bell: “I’m such a girl for the living room. I really like to stay in my nest and not move. I travel in my mind, and that's a rigorous state of journeying for me. My body isn't that interested in moving from place to place.” Freedom found in silence, alone, in the world of books. Just like me, bell was an introvert who enjoyed solitude to read, think, meditate, and write. In many ways this is my dream too, but with my dogs and Judy and lots of science fiction and fantasy books. As an empath, while at Berea, I found myself effected (affected) and desiring to follow bell’s path to be sedentary and read fiction all day. Unfortunately, such desire does not accommodate the tenure track or really any track within the world of capitalist work.

I told bell that I had been grappling with voicelessness in that first year at Berea, a kind of academic aphasia: “I have confronted silence, inarticulateness. When I say, then, that these words emerge from suffering, I refer to that personal struggle to name that location from which I come to voice – that space of my own theorizing.”9 My voice is gone. For so many years I have been stuck, in my own way, unable to put word to paper – inarticulate. And thus, I’m writing this essay as a redress for what bell and I dreamed of producing together. We were going to write something together, about our friendship. But it never happened. That was her way of supporting me, of guiding me through this voicelessness. I am trying to theorize my relationship with bell through the pain of loss. This is a difficult essay to write for many reasons, but grieving makes it the hardest: “It is not easy to name our pain, to theorize from that location.”10

In an interview I conducted with bell in 2015 for a special issue of Transcripts on “Race/Gender Revisited,” she said, “The truth is that liberatory language uses more words and takes longer to explain and understand…”11 This is not my only struggle. I struggle to explain the immensity of bell’s work in relation to a counter-hegemonic structure that works against imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy. She would talk about how this is a solitary experience, how academia can be so lonely. For all the conversation around feminism, collectivity, and community in Gender Studies classrooms, bell believed that academia was a solitary space. She did not want me to go into the academy as she saw it as a dangerous space full of intellectual vampires. She was free from academia at the end and hence, she was alone rather than lonely. One of her most cited quotes states: “I came to theory because I was hurting — the pain within me was so intense that I could not go on living. I came to theory desperate, wanting to comprehend — to grasp what was happening around and within me. Most importantly, I wanted to make the hurt go away. I saw in theory then a location for healing.”12 bell embodied this theory and we bonded over it. Theory gave us both a means to heal and to resist — a way to change our lives.

bell did not have a plan for growing old. She never thought about it because she spent all her time reading and writing. But then her hands failed her (peripheral neuropathy) and she faced a kind of crisis. She spent her life turning psychic pain into generative thought but the physical pain became too much. This is where her faith as a Buddhist Christian was so important. In fact, towards the end of her life, bell would spend the mornings reading books on Buddhism and spirituality and then would allow herself to shift to mysteries in the afternoon and evening. I still have the last bag of books I got her, which consisted of cozies (she was on an Amanda Cross kick and always loved Laurie King) and an issue of Magnolia, Joanna Gaines’ magazine. Indeed, a few of the non-cozy books that bell talked about regularly were Pleasure Activism edited by adrienne marie brown and Thick by Tressie McMillan Cottom. Yet we are all imprisoned by culture — bell loved to hate Joanna Gaines from HGTV and was obsessed with tiny homes. She wanted to build her own tiny home on land that Judy and I had recently purchased, along with a tiny cottage, in Bloomington, Indiana. She would consistently talk about it. But by then bell’s world of desire wasn’t aligning with her physical in any tenable way. This desire surfaced in words just a few months before bell passed away. By this time, she was in dire need of full-time home care, and she refused to get a caretaker. You see, Judy and I are both assistant professors starting new positions and we had neither the money, nor the time or training, to care for bell in the way she needed: 24/7. I still have guilt about setting this boundary, (“please come but we must hire you a caretaker”), around her fantasized move to her tiny home near our small cottage. I still fantasize about it too. Not only that, but I wake up every day thinking that I need/want to call bell, a painful reminder each morning of losing her.

Being with bell as she transitioned, experiencing some of her last moments of joy (she smiled a lot at the end), I came to understand how regarding oneself was for bell a Black feminist practice: “To love, to possess, to defend, to preserve, to regard oneself — to behold oneself in defiance of the gaze of more powerful others — must be recognized as an ethical practice.”13 bell’s commitment to immobility was, in the end, a means of self-regard. The audacity of bell’s immobile waywardness was its refusal for any kind of theoretical extrapolation. In other words, her immobile waywardness belonged to her and this was something she wasn’t willing to give away. And, as such, I loved her anyway.

June 2022

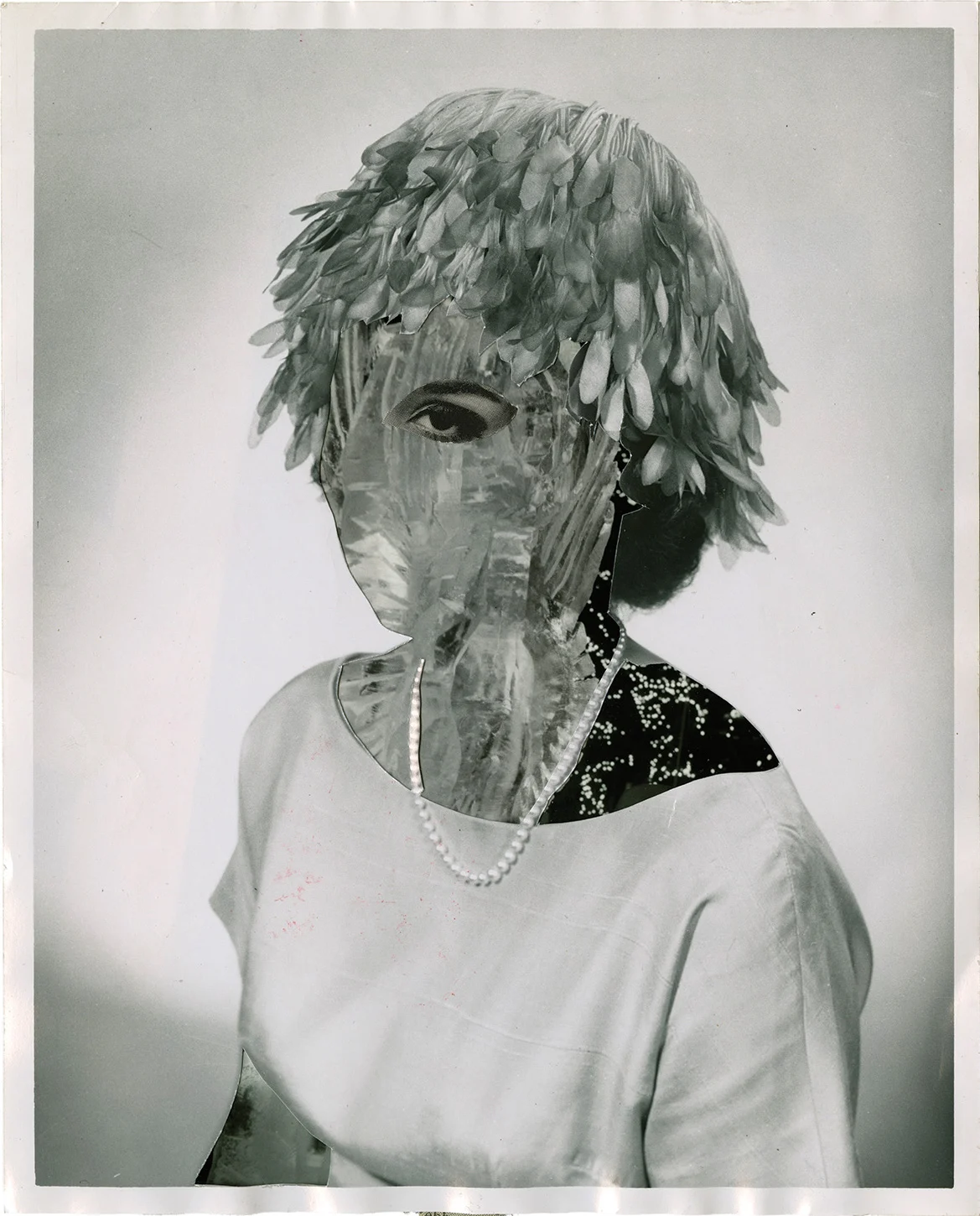

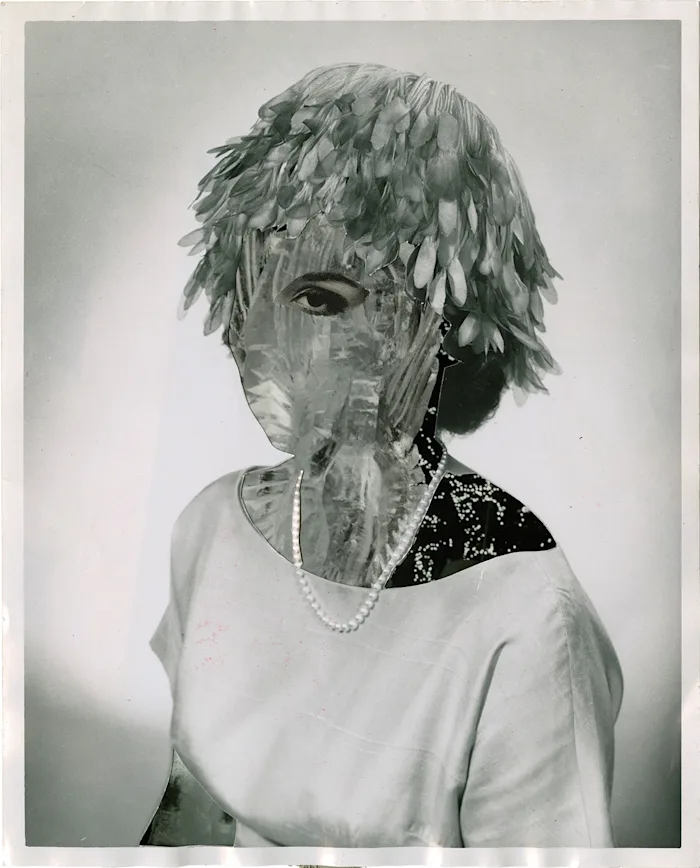

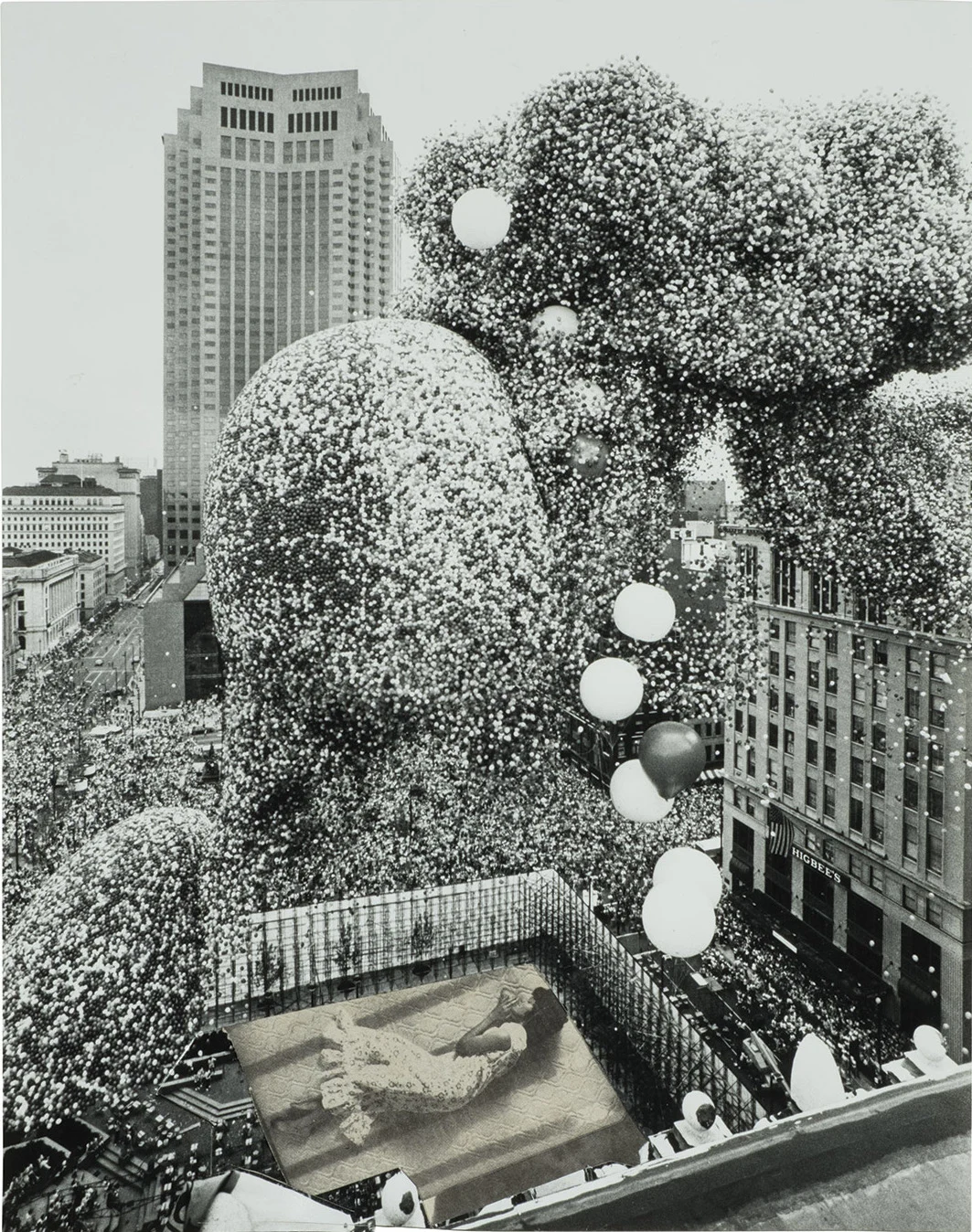

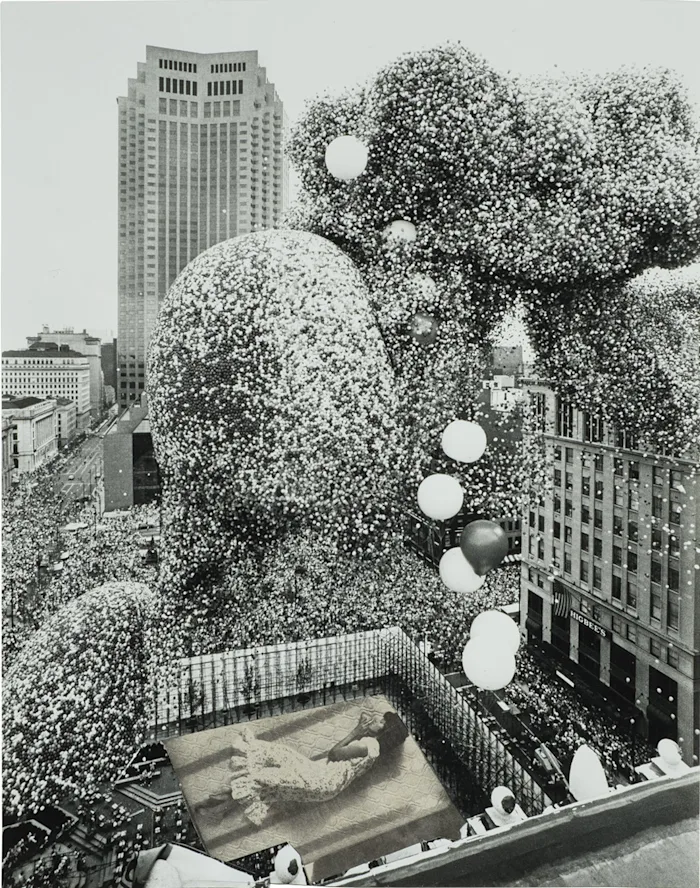

Images: Lorna Simpson

Notes

1. I would like to thank Noraedén Mora Méndez, Christina León, Judith Rodríguez, and Hugh Farrell for their help with this essay.↰

2. Kaiama Glover, A Regarded Self: Caribbean Womanhood and the Ethics of Disorderly Being, Duke University Press, 2021, 37. ↰

3. Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, Norton, 2018, 228.↰

4. Kevin Quashie, Black Aliveness, or A Poetics of Being, Duke University Press, 2021. ↰

5. During a New School conversation between Marci Blackman, Shola Lynch, and Janet Mock, titled “Are you Still a Slave?: Liberating the Black Female Body,” hooks discussed Beyonce’s Time magazine cover. In response to Mock, hooks said, “Then you are saying, from my deconstructive point of view, that she is colluding in the construction of herself as a slave. I see a part of Beyoncé that is in fact anti-feminist – that is a terrorist, especially in terms of the impact on young girls.”↰

6. bell hooks, Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics, South End Press, 1999, 148. ↰

7. bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as a Practice of Freedom, Routledge, 1994, 59.↰

8. Glover, A Regarded Self, 33. ↰

9. hooks, Yearning, 146↰

10. hooks, Teaching to Transgress, 74.↰

11. Conjuring Ain’t I a Woman: an Interview with bell hooks, Trans-Scripts 5, 2015. Online here.↰

12. hooks, Teaching to Transgress, 75. ↰

13. Glover, A Regarded Self, 222.↰