Addressing Comments, Pro and Con, on the Essay “States of Siege”

Anonymous

Shortly over a year ago, we published an anonymously-submitted essay written by some participants in the movement to Stop Cop City in Atlanta. Coming on the heels of APD and FBI raids on three houses and the arrest of John “Jack” Mazurek, “States of Siege” was met with a range of responses both favorable and quizzical. In the months that followed, it gradually became obvious that readers had interpreted its argument in quite dissimilar ways, and that a certain confusion surrounded the core positions advanced by the authors. In response, its authors set out to clarify their stance. The following response appeared in the first issue of a new political journal, Radar, initially circulated in print-only format. As Radar prepares to release its second issue, Ill Will is publishing their reply online for the first time, which will also be inserted in a reissued zine version of "States of Siege" later this week.

Printable zine here.

“States of Siege” has been misunderstood by a number of people. We say this not to discredit the comrades who disagree with the thoughts contained in this small essay, but to assert that some of these disagreements are based on erroneous claims that are not proposed within the text.

Below we summarize and respond to the strongest or most common feedback from comrades. We want the substance of our disagreements to be productive in our shared ambition to build a revolutionary movement in this lifetime.

#1: "'States of Siege' represents the departure of some comrades from mass organizing, participatory politics, and open engagement. It represents the hardening and closing-in of the comrades, to their own detriment."

SoS does not argue for the refusal or abandonment of mass organizing. It states that doing so would be "an elitist outrage, doomed to certain failure." SoS acknowledges what most participants, considering the true facts of the last three years, should admit: the movement against Cop City is simply not a mass movement. The ability to mobilize a few hundred, even a few thousand people, is not what is typically understood by "mass." Even if those numbers were increased by an order of magnitude, regularly pulling in 10,000 participants, it could hardly count as a mass phenomenon. The phrase "mass movement" should refer to political events involving at least hundreds of thousands, if not millions of participants. Given the overall population of the United States, this should not be controversial. If a movement is not a mass movement, then it is incumbent on its protagonists to figure out what they can possibly do with just a few hundred or perhaps a few thousands accomplices. We are not happy about it, but that's the reality of the situation.

The remarks related to "hardening" or "closing-in" are energetic reflections, not theoretical ones. Regardless, we think we understand the intent of these remarks. At times, through frustration and rage, some people develop a distaste and even an elitist attitude toward society, to strangers, to organizations, etc. They lose the patience for organizing with groups, for debating, for making plans. We do not agree with this perspective, but we understand it. The insurrections since 2010 have mostly all failed, despite the fact that they were indeed mass movements. Without bitterness, we know that these events have not lived up to their/our ambitions. This does not mean they have accomplished nothing at all. This does not mean that "horizontalism" is to blame, as some journalists like Vincent Bevins rush to assert. We are not among the opportunists who believe that insurrectional moments can be judged by the extent to which the capitalist system reforms, asserting itself in "stages" or in a progressive accumulation of "partial victories."

As we said, "the people will rise up." We are certain of it. This is hardly the claim of those who are closed off to mass action. Just two months after the publication of SoS, tens of thousands of students and their friends confronted police officers and administrative staff at universities across the country. US support of Israeli crimes against Palestinians has aggravated a serious and unrelenting panic in the American public. We asserted that the police we have come to know would soon introduce themselves to rebellious people across the country, and that clandestine organizing strategies would become absolutely imperative to address the coming crisis. In less than a month of protests, students across the country passed through the stages of political education required to reach our same conclusions, thanks to the most effective teacher in modern times: the billy club.

#2: "States of Siege" is a proposal to engage in urban armed struggle in the vein of the Weather Underground, Red Army Faction, or similar groups from the 1970s.

The insurrection (society in arms against the state) is an essential moment in the revolution because privileged social classes do not "wither away" automatically; they must be smashed. The modern democratic state does not hesitate to unleash fascism at home or war overseas if its interests are seriously imperiled. This should not be controversial to say. Everyone who is willing to break police lines or throw stones already understands these points.

The ruling classes defend themselves from the revolutionary potential of the masses with armed forces, police officers, prisons, and borders. If the popular classes cannot arm themselves, they must ally themselves with a section of the armed forces of the modern state, with narcotraffickers, or with foreign armies of some kind. We believe that the protagonists of the revolution against capitalism are the poor, the marginalized, and the disenfranchised of all social ranks. They must assume responsibility for, among many other things, building their own armed forces, accountable to their own social and universal needs as an alliance of lower classes. They cannot rely on bandits, mercenaries, or a company of Army men to defend them. The realities of mass armament in the Western hemisphere, including the United States, makes this question even more pressing for revolutionaries like us, who do not desire bloodshed (and who actively fear it).

We have not advocated, in SoS or elsewhere, that anarchists, communists, abolitionists, or others should begin launching armed attacks against the police, bankers, or industrialists. While it must be admitted that, from the perspective of the jailers, the use of Molotov cocktails and time-delayed devices already constitute acts of armed violence, we do appreciate that specific cultural norms surround firearms. And they should, because firearms are serious things. But the point cannot be raised to the level of a taboo.

We advocate for groups to familiarize themselves with firearms in order to generalize knowledge of them, so as to avoid "isolating the militant vanguard factions." We do not believe in forming such factions ex-nihilo. It is the self-organized actions of millions of people that will determine the successes of an insurrection. It is no contradiction to assert that people who dedicate themselves to this process must accept responsibility for certain political and technical tasks. This is already something that all activists, bail funds, and saboteurs know in their hearts, but do not often openly state. Similar to the Weathermen and RAF, we do not believe that small and dedicated groups can be counted on to advance the priorities of the social revolution all by themselves. This requires more people to become familiar with secret meetings, bone-setting, and basics of gun safety.

The more that this knowledge is taboo and specialized, the more likely it is that future movements, under high stakes and dangerous circumstances, will call on the services of designated "security" teams and militias, as they did (disastrously) in the 2020 George Floyd uprising.

#3: "'States of Siege' overemphasizes the role of subjective factors and activism, and underemphasizes the role of crises in social transformation."

Some are attracted to the arguments of the article because they want to fight fiercely against the status quo without waiting for a crisis to induce mass action. We share that feeling of urgency but we do not believe that the revolution is a coup d'etat. Without the conditions of crisis and mass mobilization, the insurrection can only be victorious by way of an authoritarian clampdown and top-down administration. If the population does not directly participate in the articulation of its own future, it will not be sympathetic to the insurgents. This is not what we are fighting for. Sadly, some self-styled anarchists (with whom we identify the most) advocate for anti-social and elitist principles of minoritarian vanguard action, mocking the idea of mass resistance and decrying popular organizations in general (which they refer to as "vanguardist" groups). If they ever found themselves on the winning end of a conflict with the state, they would be forced to run a brutal dictatorship, since the majority of people would not be organized in popular structures and would feel no ownership over the revolution. This is not possible in the modern era, so we should not dwell on it longer. The revolution cannot be made by sheer force of will, by secretive groups, or by acts of heroic destruction, even if it does, in fact, depend on all of these things in some respects.

#4: "'States of Siege' is just about forming affinity groups and doing sabotage. I agree/disagree with it, but it is not really anything I haven't heard before."

In one section, we advocate the formation of intentional small groups to develop skills and analysis with. The purpose of those groups is to ensure that as struggles develop, they are made up of many mobile, skilled, and courageous "semi-professional" groups that are experienced with fighting and familiar with combat care. Those groups would also function to prevent the isolation of individuals and groups who are dedicated to acts of sabotage or armed attacks on the state. Without a robust ecology of small groups, emerging organizations and movements will be built by people who are not invested in combative outcomes and don't know how to precipitate them. Many participants in recent Gaza solidarity protests on campuses ran directly into this problem, finding themselves in a rich social context devoid of experienced crews or groups to collaborate with.

Radicals today tend to disavow their real influence if they are anarchists, and inflate it if they are socialists. “States of Siege” acknowledges the special and unique role played by that small layer of society that joins masked demonstrations, studies struggles around the world, and attempts to bring the situation to a boil. It does so not in order to place that layer above everyone else, but in order to imbue a sense of responsibility on them/us to ensure that social struggles reach a higher level of clarity and potential.

We must take responsibility for the success of the insurrection and the victory of the revolution. That means we need to be organized. The humble proposal to form small "semi-permanent" groups is preliminary and inadequate, but could be a good starting point. Insofar as these groups should study together, acquire skills, and give one another feedback, they could be something in between a classic action-based affinity group and a cadre organization.

#5: "'States of Siege' far exaggerates the stakes or significance of the current situation. We should not be entertaining the question of the insurrection in the current juncture."

For revolutionaries, the overthrow of the social order is an actual occurrence, and it is the measure against which political events, proposals, ideas, and aspirations are to be judged. It is not a catch all phrase to refer to any and all drastic changes within a society or administration. Because it is an actual process, it occurs within the balance of forces between specific classes, groups, and interests. Those forces can be analyzed, organized, disorganized, demoralized, and empowered. And it is up to us to do all of those things, if we hope to see serious changes in our lifetimes.

It is not out of arrogance that we place our situation in conversation with history, or with the revolution. It is because we cannot afford to lose sight of what we really want.

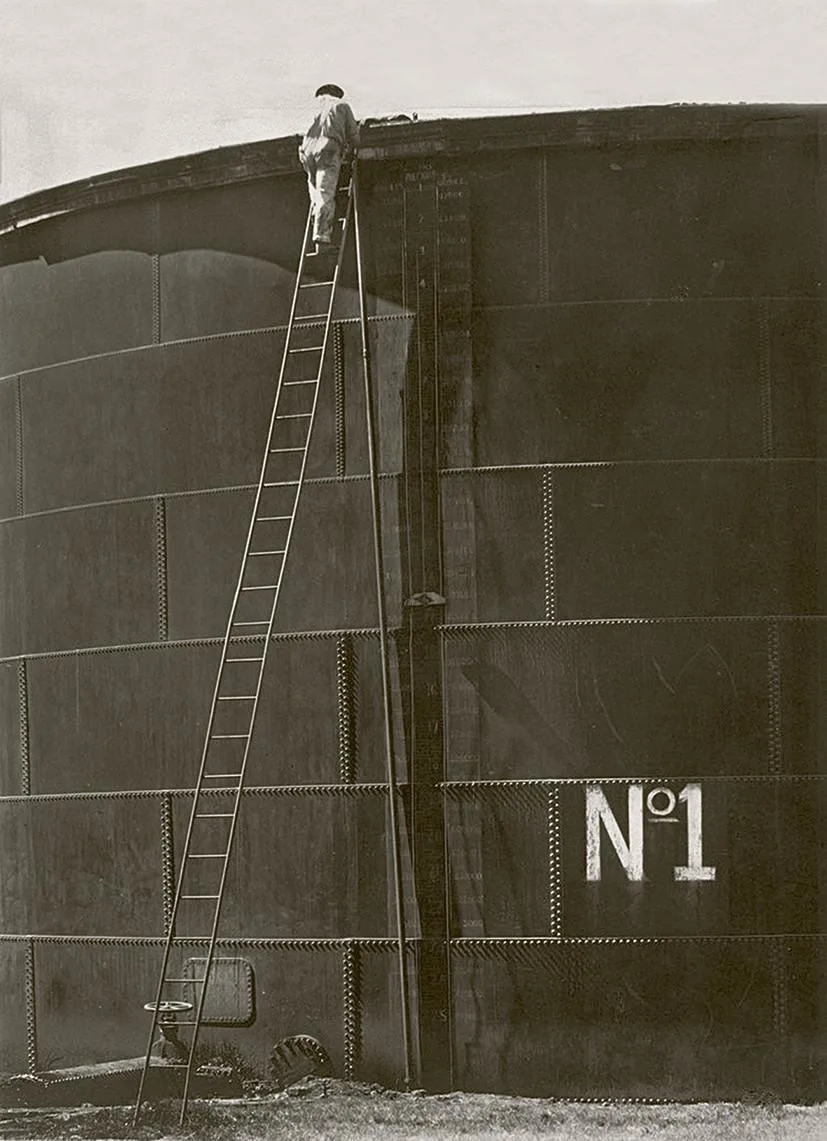

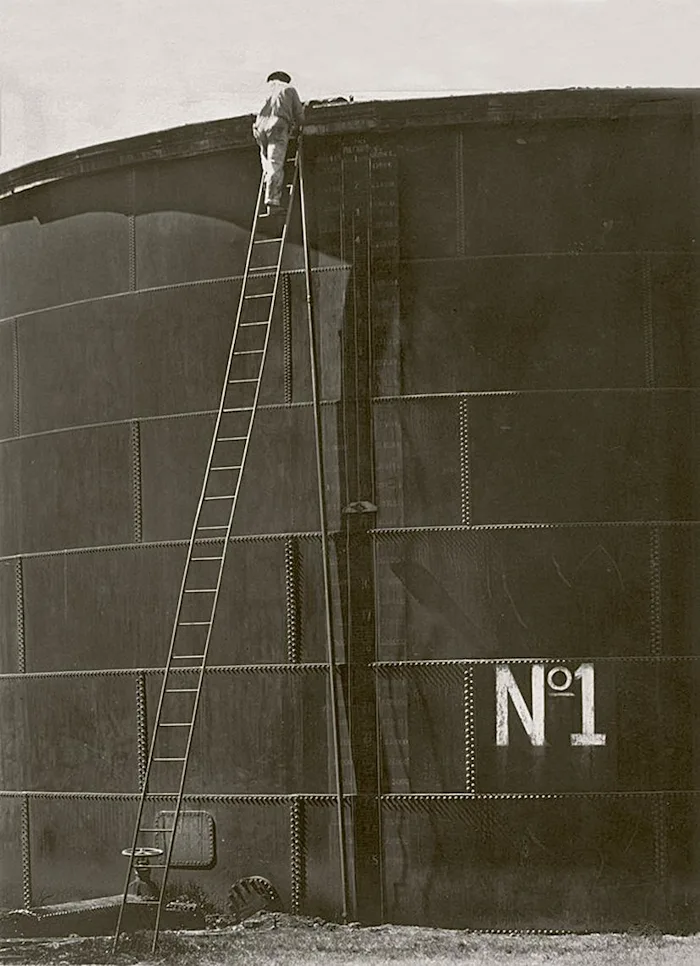

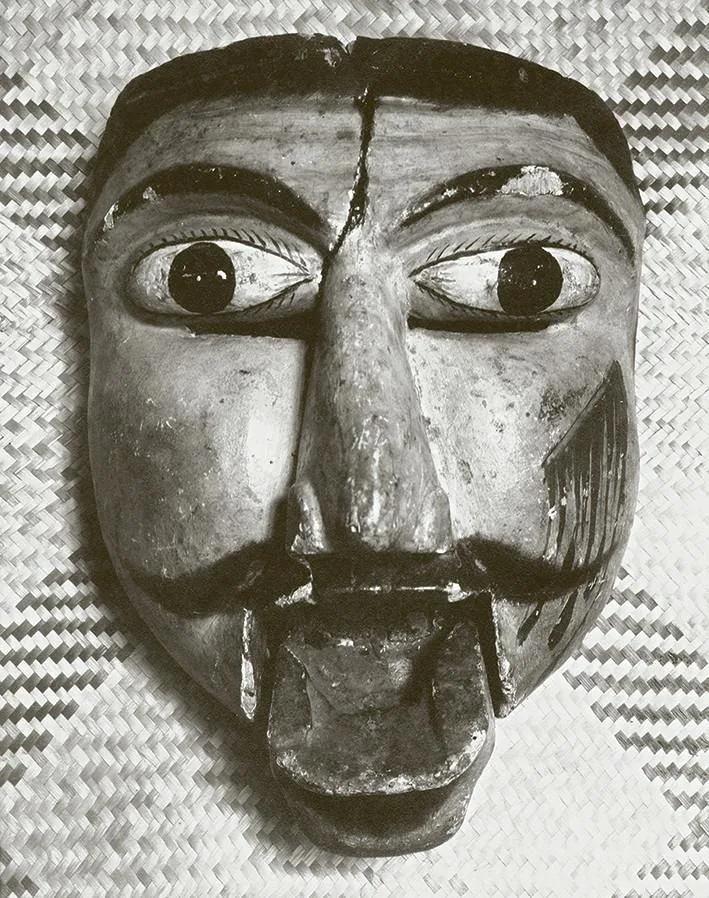

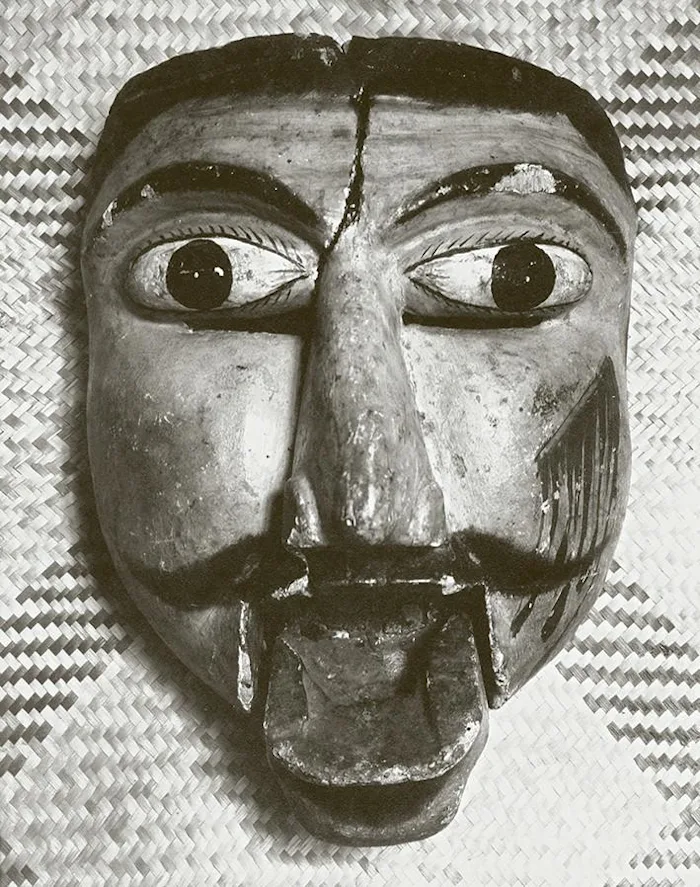

Images: Tina Modotti