Guy Debord

Giorgio Agamben

Earlier this year, Giorgio Agamben published Amicizie [Friendships], a short book in which he evokes, through seventeen brief portraits, the memory of friends who left an indelible mark on his life. Among them are Italo Calvino, Elsa Morante, Pierre Klossowski, Giorgio Caproni, and others. Below we have translated the passage written for Guy Debord.

Other languages: Español

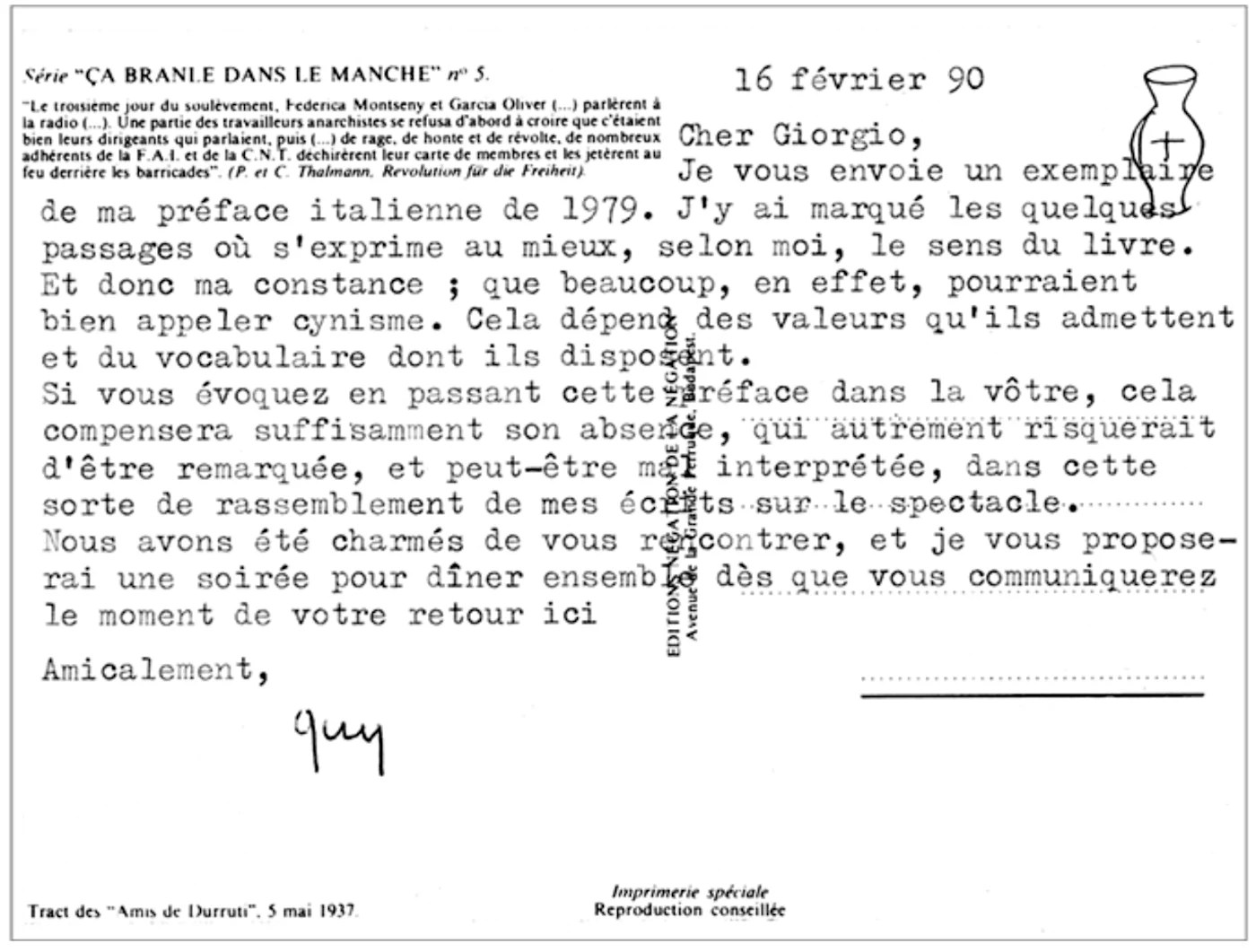

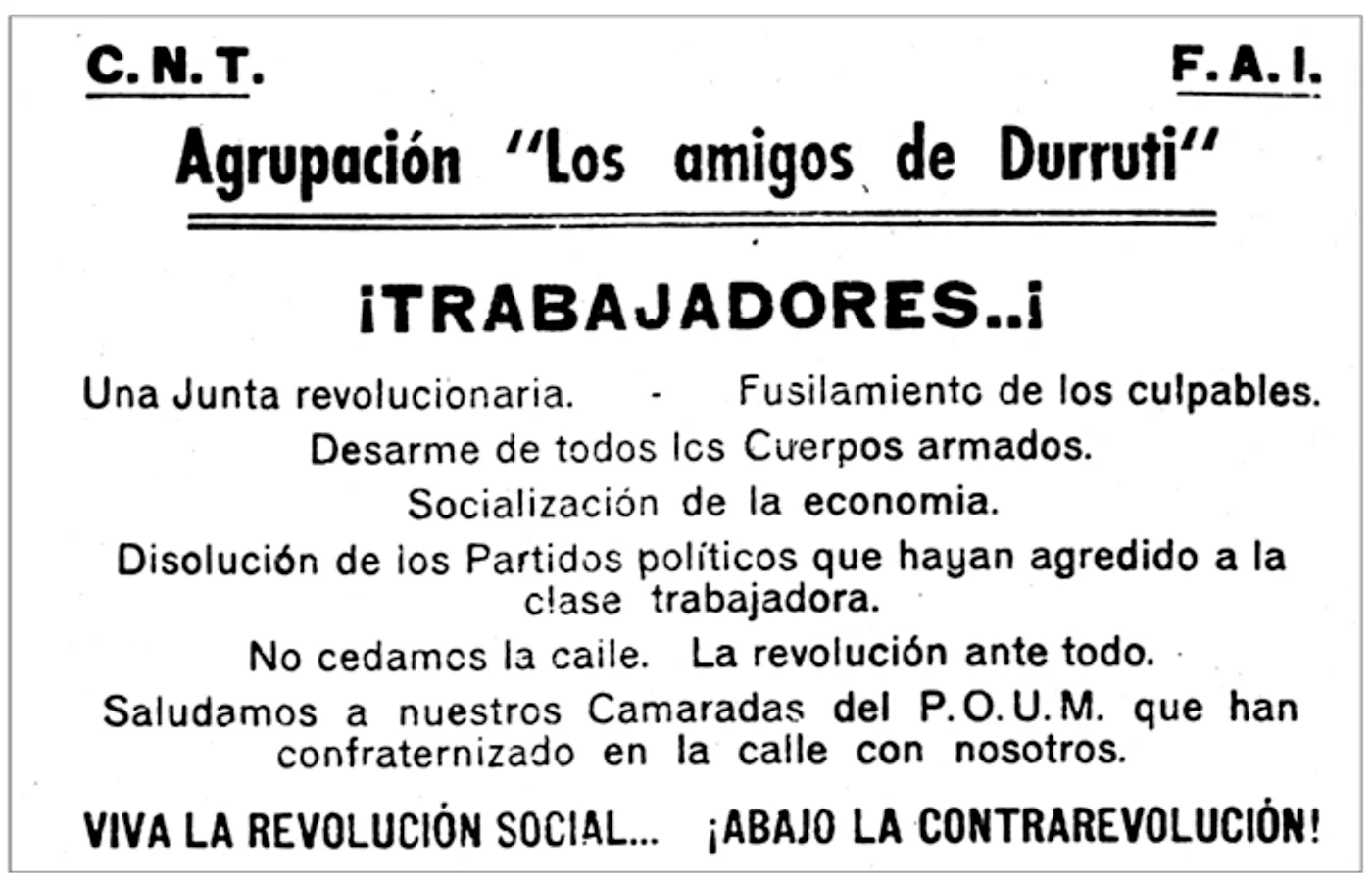

Je veux uniquement que vous sachiez combien je vous ai aimé tous le deux dès la première fois qu’on s’est rencontré et que je ne vous oublierais jamais [I just want you to know how much I loved you both from the very first time we met, and that I will never forget you]. It’s been nearly thirty years since I wrote these words to Alice Debord, in the aftermath of Guy's suicide. I still remember perfectly our first meeting in the late 1980s, in the bar of the Lutetia, the grand hotel in Montparnasse where Guy, with his shrewd taste for the pleasant aspects of bourgeois luxury, used to meet his friends. It took only a few words for us to immediately understand every detail of the political situation, which was now taking a turn for the worse. We had arrived at the same clarity, Guy from the tradition of the last, exhausted artistic avant-gardes, I from poetry and philosophy. For the first time, I found myself talking about politics without having to grapple with useless and misleading ideas and authors (in a letter Guy later wrote to me, one of these carelessly exalted authors was soberly dismissed as ce sombre dément d'Althusser), combined with the systematic exclusion of those who might have steered the so-called movements in a less disastrous direction. In any case, it was clear to both of us that one of the main obstacles preventing access to a new politics was precisely the remnants of the Marxist parties (not of Marx!) and the labor movement, unwitting accomplices (the former knowingly) of the enemy they believed they were fighting.

During our subsequent meetings at his home on Rue du Bac, the relentless subtlety — worthy of a magister of the Vico degli Strami1 or a seventeenth-century theologian — with which he stigmatized, not without irony, both capital and its twin shadows, Stalinist (the “concentrated spectacle”) and democratic (the “diffuse spectacle”), never ceased to amaze me. I can still see him sitting on the Chesterfield sofa in the middle of the room, vividly describing the situation of communist leaders through the image of a painter who, having removed the stool on which his feet had been resting, remains attached to the ceiling by his brush alone: ils ne tiennent plus que par le pinceau.

The real problem between us, however, lay elsewhere: closer and, at the same time, more impenetrable. It is curious how, in Guy, a lucid awareness of the inadequacy of private life was accompanied by a more or less conscious and almost naive conviction that there was something unique and exemplary in his existence and that of his friends. Already in one of his first films, aptly titled Critique of Separation, he evoked “that clandestinity of private life regarding which we possess nothing but pitiful documents.” And yet, in his early films and again in Panegyric, he ceaselessly parades before us the faces of his friends, the women he loved, and the houses he lived in (28 Via delle Caldaie in Florence, the country house in Champot, the Square des Missions-Étrangères in Paris — in reality, 109 Rue du Bac). There is a kind of central contradiction here that the Situationists were unable to resolve, and at the same time, a dark, unacknowledged awareness that the genuine political element lies precisely in this incommunicable and almost ridiculous clandestinity of private life. For surely it — the clandestine, our form of life — is so intimate and close that, if we try to grasp it, all we are left with is impenetrable, odious, everyday life. And yet, perhaps it is precisely this promiscuous, shadowy presence that contains the secret of politics, the other side of the arcanum imperii on which every biography and every revolution is shipwrecked. The phrase, “construction of situations,” from which the Situationists took their name, implied that it was their task to find something like “the Northwest Passage of the geography of real life.” But Guy, who was so skilled and astute when it came to analyzing alienated forms of existence in the society of the spectacle, appeared candid and defenseless whenever he attempted to communicate the form of his life, to face up to and demystify this clandestine element [la clandestina] with whom he shared his journey to the very end. It was the political meaning of this clandestine element — which Aristotle, under the name of zoē, had both excluded and included in the city — that I was beginning to question in those same years. I too was searching, in another mode, for the Northwest Passage of the geography of real life.

One evening in Paris, when I told her that many young people in Italy were still interested in Guy's writings and were waiting to hear from him, Alice replied: “On existe, cela devrait suffire” [we exist, that should suffice]. What did this “on existe” mean? Of course, in those years, they lived in seclusion and without a telephone between the Rue du Bac and Champot (it was understood that when I arrived in Paris I would write a letter, which would invariably be followed by an invitation to dinner). Their existence was, so to speak, entirely flattened [integralmente appiattita] by the clandestinity of their private lives. What, then, could “on existe” mean? Existence — pure being, this concept so fundamental in every sense to Western philosophy — is constitutively bound up with life. “To be,” writes Aristotle, “for living beings, means to live.” And centuries later, Nietzsche clarifies: “To be: we have no other representation of it than to live.”

Guy did not consider himself a philosopher but, as he once told me, a strategist. And yet, bringing to light — beyond all vitalism — the intimate intertwining of being and living was certainly then, as it is today, the unavoidable task of thought and politics.

Guy had no regard for his contemporaries and expected nothing from them. For him, the political question had been reduced to the stark alternative of homme ou cave (to explain this slang expression, with which I was unfamiliar, he referred me to Simonin's novel Le cave se rebiffe, which he particularly liked). Guy was, consistently, a man of few, yet insistent readings — in the letter he wrote me after reading my “Marginal Notes on Comments on the Society of the Spectacle,” he referred to the authors I had quoted as quelques exotiques que j'ignore très regrettablement et à quatre ou cinq français que je ne veux pas du tout lire [a few exotic ones that I unfortunately don't know, and four or five French ones that I have no interest in reading]. The fact remains that, if you despair of your fellow human beings, you also despair of yourself, and Guy never managed to overcome this despair, even when, in one of his first films, he said of himself and his friends that their encounters were like “signals emanating from a more intense life, a life that has not truly been found.” His indecision between the clandestinity of private life — which, with the passing of time, must have seemed increasingly elusive [sfuggente] and perhaps intolerable to him — and the historical life in which it was inscribed betrays a difficulty that no one can delude themselves into thinking they have resolved once and for all. The clandestine life that Guy pursued has become even more elusive today; and yet, only if thought is able to find the genuinely political element hidden within the clandestinity of singular existence will politics be able to emerge from its abstractness, and individual biography from its idiocy.

Translated by Ill Will

Notes

1. “Vico degli Strami”: historical street in Naples associated with learned, often theological or legal scholasticism. —trans.↰