We Wanted to Destroy the University

Ben Morea

In the following interview, historian Abigail Susik sits down with Ben Morea — cofounder of New York City’s legendary insurrectional street gang, Up Against the Wall, Motherfucker! — to discuss their participation in the April 1968 occupation of Columbia University. When students took over Columbia once again this past spring (2024) in solidarity with Palestinians in Gaza, Morea visited the occupation and met with protestors. The present interview emerged from this experience.

As university students everywhere return to campus this month and next, how might perspectives forged through previous generations of militancy inform current-day struggles? How has the landscape changed? What remains of the 20th-century revolutionary form of life today?

Abigail Susik: What were some of the circumstances that brought Up Against the Wall Motherfucker (UAW/MF) to the student occupation of buildings on Columbia University’s campus in late April 1968, just a few months after coming together as a group?

Ben Morea: Up Against the Wall was a nominal chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), not because we believed in SDS particularly, but because, number one, we then could have direct contact with students. We could share things with the students, but we could also help them. The SDS was, at that moment, struggling against Progressive Labor, which was a Maoist authoritarian movement trying to take over SDS. We could ally with SDS against that takeover. Plus, a lot of the SDS people were influenced by us. One particular SDS group included a lot of people who became Weathermen. They all were influenced by our style, beliefs, and militancy, and that one group of SDS people really went to the extreme, in a sense, when SDS broke up following the Columbia occupation.

Also one of the founders of the Motherfuckers was Osha Neumann, Marcuse’s stepson. Osha’s brother was an officer in the Columbia SDS, one of the more militant chapters.

How well acquainted were you with Mark Rudd, probably the most prominent member of the Columbia chapter of the SDS during the campus occupation?

BM: I knew Rudd really well before the occupation because that Columbia SDS chapter was really close to the Motherfuckers and actually stayed with us on occasion. They came to our gatherings and ate our free hot meals. They were with us a lot. Rudd was one of our friends. His group was influenced by us, including Jeff Jones. They were nominally radical, but over time they became more so. They took our style, not our politics.

What did you think of the fact that Rudd’s letter to Columbia’s president stated, "[y]ou call for order and respect for authority; we call for justice, freedom, and socialism... [u]p against the wall, motherfucker, this is a stick-up”? Was it strange to have Rudd invoke the Motherfuckers while also using the word socialism?

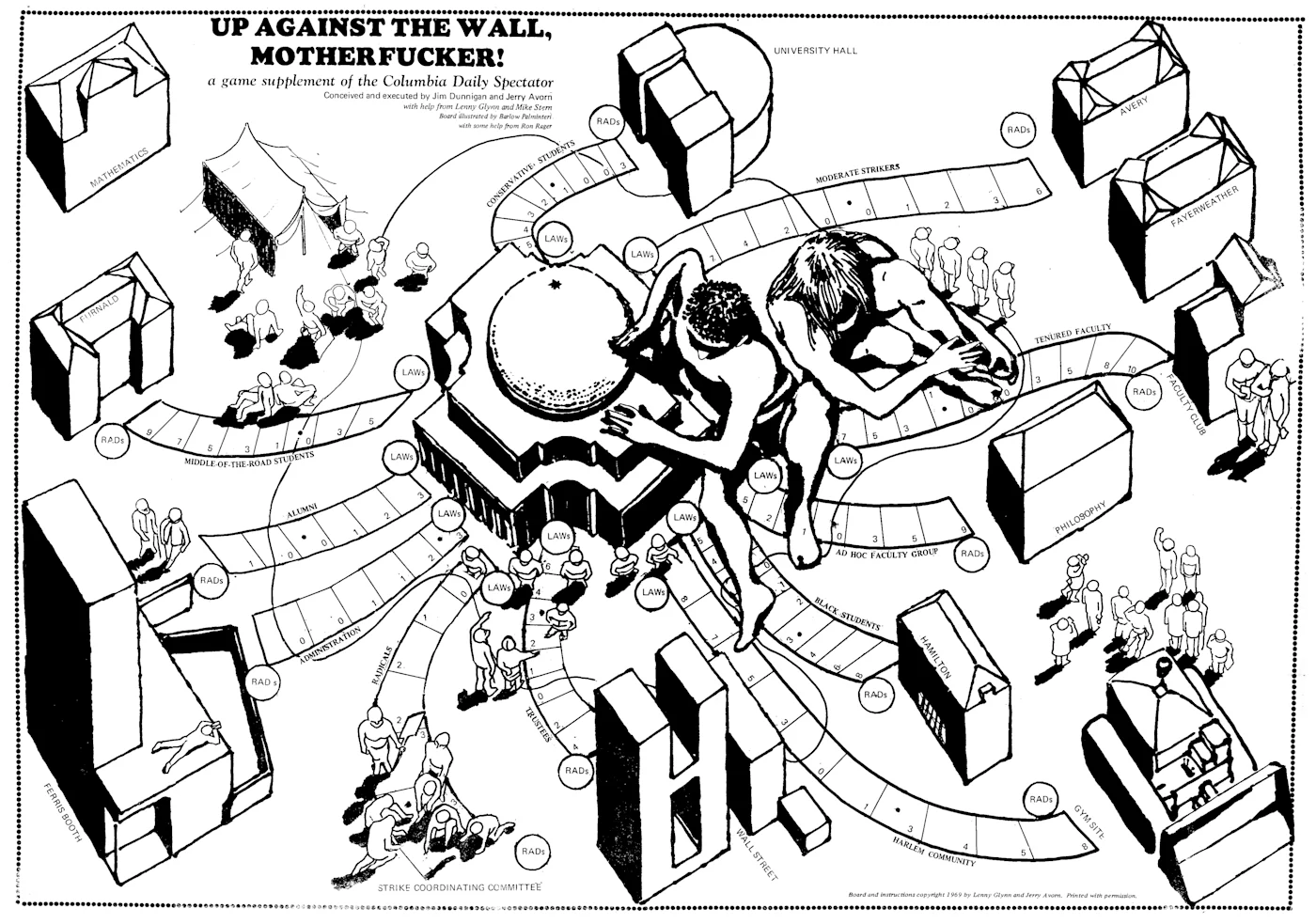

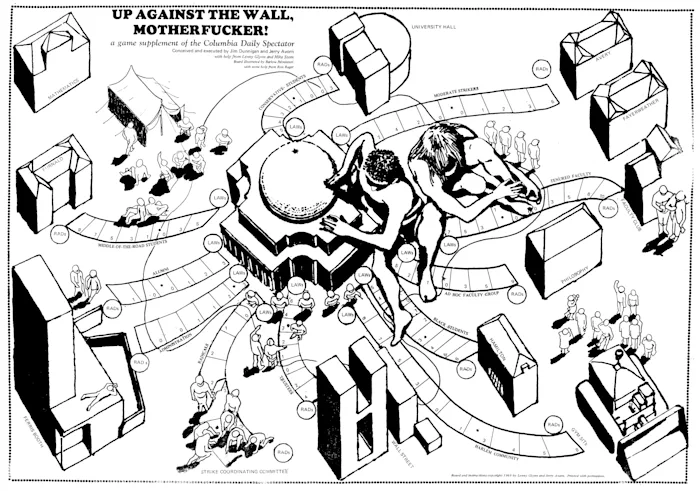

I was also surprised to see that around this time, the Columbia SDS chapter was publishing a newspaper called Up Against the Wall. Rudd’s group must have been deeply influenced by you. There was even a protest simulation game designed in 1969 by Columbia University Students called, “UP AGAINST THE WALL, MOTHERFUCKER!”

Rudd took that from us, yes. Rudd and the Columbia SDS group were more socialist, but basically, they were extreme left, like Marcuse, or even further left. They weren’t totally radical. They took some of their radicalsim from us. But, with the Weathermen, they took it in a Leninist direction, which we opposed. Meaning that they saw revolution as having a small radical origin, a vanguard. They were more hierarchical and more organized into a party-type structure. As anarchists, my Family didn’t see it that way. We saw ourselves as being made up of small groups but also understood that we were part of the general public. We thought: yes, you should have small radical groups, but you should also have the general strike. When you forget the general strike and just concentrate on the small groups, that sends the wrong message.

What was the message that Up Against the Wall was trying to send out in a non-vanguardist fashion?

We used the phrase “propaganda of the deed.” In other words, it’s the deed that you are trying to educate people with. It’s not necessarily the act that is important; it’s what that act could lead to. It makes a statement. It’s a physical manifestation of an idea, but it’s also more than the act itself. It’s a way of teaching or showing.

Can you say anything else about your relationship to Rudd and the Weather Underground after they formed in ’69?

In the process of the radicalization of the SDS, it was necessary that they would turn into a smaller group of people. Isolating and becoming a small group of radicals and militants was not a mistake. It was correct. But the mistake was to then think that that shift to small groups was an ideological need rather than a technical need, a militaristic need. It enhanced this elitism.

But, I was particularly close to one person who was in the Columbia SDS chapter and was a Marxist Leninist and who became a founding member of the Weathermen. He stayed with me in the mountains for a month when he was hiding out. I told him I would not turn him away.

Let’s return to the spring of 1968 at Columbia University. To what degree was Up Against the Wall there to oppose particular issues, like the Vietnam War, through the occupation of the university?

Well, that's what a lot of people think. That the war was the main issue. And that's not untrue, but it's not the whole story. Five buildings were taken. The first building, Hamilton Hall, was occupied by the Black students and Columbia's Student Afro-American Society (SAS). Nobody gives them credit, but they started the occupation. They were concerned about Vietnam. That was part of it. But they also were concerned that that part of Harlem, that north end of Manhattan, was in terms of real estate, controlled by Columbia. Columbia was moving to displace the Black population with students and non-Blacks. Though I'm sure they won't admit it, Columbia made an active move to remove the Black people out of that area surrounding them. So, the first building was taken by Black students, who emphasized their opposition to Vietnam, but also the fact that their local community was being decimated by Columbia as a slum landlord.

Then, the Black students involved SDS in their occupation, but SDS was also more interested in other agendas, like Vietnam and opposition to American hegemony throughout the world. The SDS was less racial and more political. So, when SDS got involved, they took three more buildings. There were four buildings altogether, and they contacted us and said there was a fifth building if we wanted to take it. That was the Math building.

Tell me about the act of seizing the Math building.

We said to the SDS, “yes, we’ll take it,” and we did. When we looked at it, some liberal-type students had already started moving into the ground floor. But we wanted the second floor, because logistically it's easier to defend the second floor. We immobilized the elevator immediately, so you had to use the stairs, and then we booby-trapped the stairs so there was no way in for law enforcement.

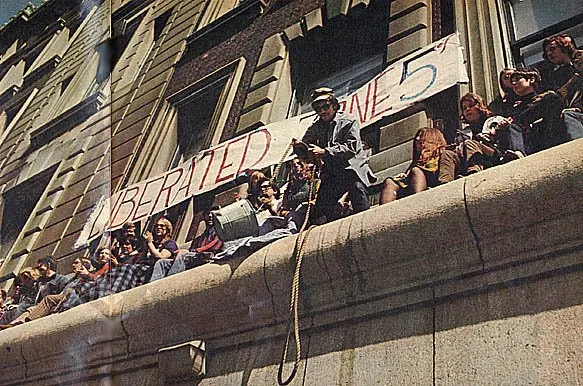

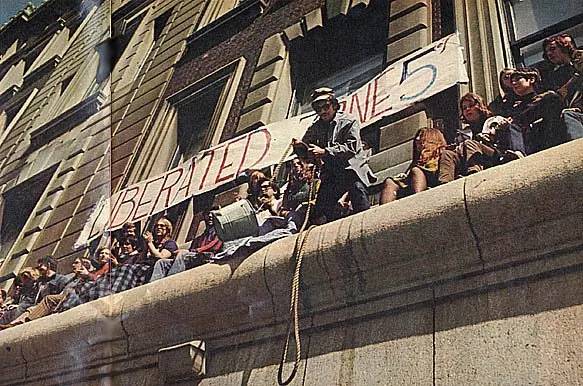

And once you were inside, how did you maintain yourselves over the course of those days of occupation? Did you have anything to do with the banner on the Math building that said “Liberated Zone 5,” or the flag that was erected on top of the building?

It felt like we were there for two weeks. The police made a blockade to keep food out, but we broke the blockade physically. I got knocked out at that time. But there were people getting in the building anyway. Valerie Solanas got in somehow just to visit, to talk with me. And there was a veteran of the Durruti Column in Spain who I was friendly with and who used to hang out with us. He showed his ID from a halfway house for mentally incapacitated people and they let him in. It was a total lockdown in the buildings, but we were sneaking food in. We all made efforts to get food in over the course of that week or so. I don’t know anything about the banner or flag.

How many members of your group were in the building? Did everybody know it was UAW/MF inside, and were you identifiable as such?

We never called our Family an organization. You know, when you throw a rock in the water, you have these rings that float out. Our family was like that, a group of maybe 25 people. And then the first wave is another 30, the second, another 50, and so on. Our core group was in the building, but then parts of other groups joined us. Then some students came who were influenced by us or were interested in joining us because it was clear that we were the main occupants of the second floor.

It’s not accurate to say that we were a street gang, but we made that impression. A lot of our family members were from the street. Some of my close brothers and I had jean jackets that somebody made for us with the Motherfuckers in white letters on the back.

When you read about the occupation, it’s common to encounter the observation that the Math Building was known to be held by the most radical students.” Can you tell me more about the defenses you set up?

We attached furniture to the ceiling so it could be dropped on the stairs if anybody came up. Then we had the fire hoses. All the fire hoses were in key places, aimed, and fire axes. They were their weapons, so to speak, just applied to different purposes. I can’t say and I won’t say if any of the students had other weapons. That’s a remote possibility. Usually it was the women in our group who carried weapons under their clothes. Somebody cut the wires of the elevator. As far as I know, no other occupied building had that kind of fortification.

What were some of your Family’s aims with the occupation? Were you also attacking the institution of the university as such?

We were there to support the Black students and the SDS, and to some degree, the issue of Vietnam came up for us. But, overall it was a revolutionary act that was a way to bring about the realization that something was amiss and had to be corrected. It was just one part of our whole life. Yes, we wanted to destroy the university.

Which is why Up Against the Wall wasn’t satisfied with the idea of “protest,” right?

The object is not to protest. The object is to make a change. There is overlap with protesting, and some parallels exist. But the main thing isn’t to protest, meaning you are bringing pressure to bear morally. We didn’t want to bring pressure. We wanted to stop things.

How did the Columbia occupation align with some of your prior activities?

Renaming Wall Street as “War Street” was the culmination of Black Mask becoming Up Against the Wall. That was an action already starting to move in the direction of what became UAW/MF. Prior to that, Black Mask was an art theoretical movement all about prints, designs, and posters. The art movements of the 20s and 30s, like Dada and surrealism, were our role models. But with UAW/MF, our goals and methodology changed. It was more about action. Dumping Garbage at Lincoln Center in February of 1968 during a citywide trash workers’ strike was our first action. But we did continue to make posters. We were invited to do the centerfold of RAT Subterranean News whenever we wanted, and I usually designed one every third week with my partner Joan. She and many of the other women Family members were with us at Columbia.

How did the occupation of the Math building end?

In four of the buildings, the students were physically removed, often violently. There were a lot of beatings. The only building that was not forcefully removed was us, because it was so booby-trapped that the police would not come in. We invited them. We told them: come in, take us out. But you gotta come in first. So, they negotiated our withdrawal under the premise that, since the other four buildings are gone, why hold out? Which made sense. A lot of the other buildings had extra charges added, like trespassing, or resisting, but we didn't have anything added. We negotiated our withdrawal. I think we were just given a summons.

I know you talked with some of the students protesting against the Israeli genocide in Gaza at Columbia this spring. What were some of the things you discussed?

I told them that it's a totally different world with the cops these days. These guys are militarized. We were up against police who were overweight, under-trained, and in terrible shape. We were better armed than them. But it’s altogether different now. It doesn't mean you can't do something. It just means that what you do is different, and more difficult. There can be a high level of resistance. It’s up to people. I can’t tell them, but there can be.

Do you see any parallels between your group’s struggle and the one going on now in response to the Israeli genocidal offensive in Gaza?

For months, I’ve been asking myself, what's wrong with this generation? Vietnam was our test, and we jumped to it. We stopped it. Gaza is this generation's test, and they haven't stopped it. People should see what’s happening there and realize that they should have moved sooner, and they didn’t. Now, though it might be late, they’ve gotta move. Pressure can be put on. Like what the students tried with divestiture. But that has to be resurrected with a different tactic.

There has to be an effort to make the US back off of support for Israel. That's clear. It's up to the students to figure out how far they have to go and what they have to do. It's not up to me to tell them. But I guarantee you, it can be stopped.

But nobody's willing. I can't do it alone. Nobody's willing to do what is necessary. But it can be stopped.

It can't be stopped if the resolve is not there that it must be stopped.

It will be stopped if people make that resolution and live up to it and do whatever is necessary. It can be stopped.

So, you see some strong parallels between then and now?

Yes, but also differences. We decided: either we end Vietnam, or we die. We wouldn’t survive it. That's how much commitment we had. We were suicide warriors. That’s how it had to be.

Now, it’s a different time, it takes a different response. I can't tell people what they should do. If I don't do it myself, I have no right to tell someone else to do it. I don't want to take that role of telling people to do certain things that I'm not able to do anymore. It’s not correct to tell people to put themselves on the line.

Is this where Up Against the Wall’s rejection of non-violent resistance comes in? Members of your affinity group would die for one another and your cause.

If it happens in the struggle, I am in favor of the struggle, whatever form opposition takes. Take for instance the Chicano uprising, when a sheriff was killed during the occupation of the police station. There was supposedly an incident of cannibalism. There's always been that talk, and I've never condemned it. It was just a way of expressing complete hate for the oppressor, the real oppressor, and so, it doesn’t matter to me. It's just a way of saying: take them out. You have to do whatever you have to do. And that's what's important, not whether some incident happened or didn't happen. It didn't matter to me.

I was very close with Judith Malina and the people in the Living Theater. They were my aesthetic parents. She was as supportive as she could be, considering she was nonviolent. She defended me all the time, saying, like: that's not my way, but I support his opposition, his struggle.

You’re not inflicting violence on people. You're defending yourself and your struggle. By any means necessary. It's a matter of defense. I'm 100% opposed to terrorism. To me, that's a wasted form of violence. Defense is the issue, not terror against humans.

The Cheyenne had suicide warriors called dog soldiers. They carried a stake with them, and if their band was threatened with extermination, they would stake themselves to the ground and never move, never leave. It's not about inflicting violence. It's about defending against violence.

August 2024