The Devil's Night: On the Ungovernable Spirit of Halloween

Anonymous

Before plastic fangs and fake blood, October 31st was a day of rebellion; the history of Halloween spans five hundred years and two continents, featuring pagan rebels in the Medieval British Isles, the European witch hunts, Irish migration to the States, and widespread arson in Detroit in the 1980s.

Other languages: Español, Italiano

We had no words to give weight and form to the feeling of cool October nights in Detroit. After we smashed the winking eyes of streetlights the dark on the streets pressed its body close and wrapped its cloak around us; and we could not speak.

We had no words dark enough for the Devil’s Night moon – fat, full, and silver – that we could not smash. It shined white on us as we crept between hedges and houses, crawled onto roofs, and dashed through alleys. It slashed at our heels as we hopped rattly, metal fences silently as alley cats.

We had no words for these: the feel of dark the moon weaving silver onto the metal webs of city fences the ships screaming into the mouth of the Rouge River, and the lights of tall buildings blinking through the stinging smoke of a burning Detroit. —Carmen Lowe, The Metaphysics of Vandalism (1989)

Origins of the Halloween Spirit (c. 1000 BCE)

The Halloween machine turns the world upside down. One’s identity can be discarded with impunity. Men dress as women and vice versa. Authority can be mocked and circumvented. And more important, graves open and the departed return. —David Skal

There are demons at the edge of my vision. There are ghosts in the machine. —Edgar Allen Poe

Despite Halloween’s popularity across much of North America, its history is poorly understood by many of its celebrants, likely due to its dark, unsavory, and disorderly nature. Though its calendar date and etymology are undeniably Christian (from “All Hallows’ Evening,” the night before All Saints’ Day on November 1st), the spirit that animates this Halloween machine is commonly held to originate from the pagan new year celebrations of the Keltoi people (or Celts) of what is now known as Ireland.1

The Keltoi, whose name is likely derived from kel-, the Indo-European prefix for “hidden,” were a diverse constellation of Celtic-speaking tribes that spread across much of Europe and the British Isles between the Iron Age and Early Middle Ages, even occupying Rome for a period of time around 400 BCE.2 Because of these hidden people’s refusal to commit their oral history and scholarship to written records, much of the most spectacular accounts of these “primitive” pagans and their “bloodthirsty” human sacrifice have been written by their imperial enemies such as Julius Caesar and therefore should be considered suspect at best.3

What is known by historians, however, is that many Keltoi of the British Isles believed in an afterlife called Tirnat Samhraidh, or the “Land of Summer.” The doors to this otherworld were only opened once a year on Samhain (pronounced SOW-in), the period between the two nights of October 31st and November 1st.4 According to Nicholas Rogers, author of Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night,

Samhain beckoned to winter and the dark nights ahead. It was quintessentially ‘an old pastoral and agricultural festival,’ wrote J.A. MacCulloch, ‘which in time came to be looked upon as affording assistance to the powers of growth in their conflict with the powers of blight.’ [...] It was also a period of supernatural intensity, when the forces of darkness and decay were said to be abroad, spilling out from the sidh, the ancient mounds or barrows of the countryside. To ward off these spirits, the Irish built huge, symbolically regenerative bonfires and invoked the help of the gods through animal and perhaps even human sacrifice. [...] In Celtic lore, it marked the boundary between summer and winter, light and darkness. In this respect, Samhain can be seen as a threshold, or what anthropologists would call a liminal festival. It was a moment of ritual transition and altered states. [...] It represented a time out of time, a brief interval ‘when the normal order of the universe is suspended’ and ‘charged with a peculiar preternatural energy.5

These “liminal interludes,” as Celtic historian Barry Cunliffe terms them, were particularly dangerous because “they were times when anything could happen and it was only by careful adherence to ritual and propitiation that a precarious order could be maintained.”6 Lisa Morton, a historian of Halloween, adds:

A Celtic day began when the sun went down, and so Samhain started with the onset of darkness on 31 October, with a feast celebrating the recent harvest and temporary abundance of food. Some archaeological evidence suggests that Samhain may have been the only time when the Celts had ready access to an abundance of alcohol, and the surviving accounts of the festival – in which drunkenness always seems to occur – support this as well [...] It was also – with Beltane or 1 May – one of the two most important days in Celtic heroic tales, which almost invariably contain some frightening element. In one early story, the Formorians, a race of demonic giants who have conquered Ireland after a great battle, demand a yearly tax of two-thirds of the subdued survivors’ corn, milk, and children, to be paid each year on Samhain. The Tuatha de Danann, a race of godlike, benevolent ancestors chronicled in Celtic mythology, battle against the Fomorians for years, but it takes the Morrigan, a mother god, and the hero Angus Og to finally drive the monsters from Ireland – on Samhain, of course.7

In these two brief accounts of Samhain once can already find elements of the spirit that came to haunt celebrations of Halloween for the coming two millennia – particularly those of liminality, excess, celebration, fear, mischief, demonic forces, darkness, retribution, and, perhaps most important to this essay, rebellion. From the anti-Christian heresy of the medieval British Isles to the widespread arson of 1980s Detroit, this essay traces these lit fuses through several explosive historical periods to illustrate how Halloween’s enduring spirit of disorder possessed each one.

The Fires of the Sabbat (c. 700-1600 C.E.)

In the history of Christianity, witchcraft is an episode in the long struggle between authority and order on one side and prophecy and rebellion on the other. —Jeffrey Russell

For rebellion is as the sin of witchcraft, and stubbornness is as iniquity and idolatry. —1 Samuel, 15:23

Though Samhain provided Halloween with these raw thematic materials, it actually gave the holiday very little in terms of lasting icons or concrete practices, excepting bonfires. These traditions, including the very name of Halloween, came much later in the Middle Ages, with the violent imposition of Christianity and its holy days: All Souls’ and All Saints’ Day.

By the seventh century, the Catholic Church had spread throughout most of Europe; missionaries – including St. Patrick, who would later become the patron saint of Ireland – had successfully converted the Pagan Celts. The Church had found that conversion was far more successful when attempts were made to offer clear alternatives to existing calendar celebrations, rather than simply stamping them out. [...] This doctrine, known as syncretism, even replaced lesser pagan gods with Catholic saints.8

Originally celebrated on May 13th as a remembrance of Christian martyrs who had died at the hands of pagans, Lemuria (as it was first known) was moved to November 1st in the mid-eighth century by Pope Gregory III and rebranded as a more palatable, positive celebration of “all the saints.” Later, around 1000 CE, the church added All Souls’ Day on November 2nd, conveniently bookending the celebration with an opportunity to pray for the souls of the deceased that were trapped in Purgatory. According to Morton, however, “it seems more likely that the gloomy, ghostly new celebration was added to cement the transformation of Samhain from pagan to Christian holiday.”9 This practice of de-clawing a subversive tradition by institutionalizing it – or recuperation, as the Situationists might later call it – will later appear in moments of crisis and excess in order to restore order to future Halloweens.

Three centuries later, the gloomy nature of All Souls’ Day transformed from an exceptional, temporary celebration to the daily reality of most Europeans as the Black Death began to spread throughout the western hemisphere. Arriving in 1346 and peaking around 1350, the plague killed as much as 60 percent of Europe’s population and left the surviving population with an unavoidable preoccupation with death. This, coupled with the simultaneous popularity of the new printing press, led to the mass circulation of Danse Macabre imagery and a generalized perception of Death as a personified subject, an icon still present in modern celebrations of Halloween.10 Though the figure of Death was originally portrayed as an animated skeleton, the opportunity was quickly seized by the Church and proto-capitalists to repurpose its image to target a rebellious population which they had long considered a threat but were now strong enough to destroy: the witch.

According to Arthur Evans’ Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture,

Despite its contempt for magic, the early church did not organize a full-scale attack against magicians and witches because it was not yet strong enough. The Christianity of the early middle ages was largely an affair of the King and upper class of warlords. The rest of society remained pagan. In addition, early medieval Christians were hampered by a general breakdown of centralized authority in both church and state. Anarchy favored paganism.

However, Evans continues,

By the early thirteenth century, [...] with the election of Pope Innocent III, the church was much better organized and ready to act. Its immediate target was heresy: the numerous and wide spread attempts to combine traditional Christianity with elements of the old religion. To deal with this, the church launched crusades and started the Holy Inquisition. [...] Now it began to look at the historical sources of heresy – the surviving old religion that modern historians view as ‘folklore,’ ‘peasant fantasy,’ and ‘strange fertility rites.’ Feeling its privilege, power, and world view threatened by these sources, the fifteenth century ruling class fantasized that Satan was conspiring to overthrow the power of Christ’s church on earth. Christian intellectuals fed on this and they, not the lower classes, thus created the stereotype of demonic witchcraft. In 1451, Pope Nicholas V declared that magical activities were subject to the Inquisition. And in 1484, Pope Innocent VIII gave papal backing to the intellectuals’ view that witches were demon-worshipping heretics.11

Though this figure of the Abrahamic Satan may have also been intentionally constructed to transform the horned Pagan gods – such as the Celts’ Cernunnos – into an figure of enmity, his first appearance (of many) in relation to Halloween is as the leader (and sometimes sex partner) of the witches.12 This conceptual marriage of Satan and the witch heralded the beginning of what Silvia Federici calls The Great European Witch-Hunt. In Caliban and the Witch, Federici traces the lineage of this coordinated mass murder beyond just the Christian elite’s fear of paganism into a whole world of popular peasant revolts and the powerful, undomesticated women13 who likely organized them. By highlighting that many of these women lived alone, relied on public assistance, were sexually “promiscuous,” and encouraged non-procreative sex (by means of contraception and abortions), early state-builders were able target these embodied impediments to patriarchal governance, heteronormativity, population growth, compulsory labor, domestication, and social order – in a word, civilization – by portraying them as enemies to life itself:14

Witches were accused of conspiring to destroy the generative power of humans and animals, of procuring abortions, and of belonging to an infanticidal sect devoted to killing children and offering them to the devil. In the popular imagination as well, the witch came to be associated with a lecherous old woman, hostile to new life, who fed upon infant flesh or used children’s bodies to make her magical potions.15

“The goal of state violence is not to inflict pain,” Carole Nagengast writes, “it is the social project of creating punishable categories of people, forging and maintaining boundaries among them, and building the consensus around those categories that specifies and enforces behavioral norms and legitimates and de-legitimates specific groups.”16 Though this targeted population was likely quite heterogenous, whose activities today may be likened to those of midwives, abortionists, sex workers, revolutionaries, or popular healers (among many other subjectivities), their enemies were able to collapse their few commonalities into the punishable and inescapable category of the witch. This cursed identity, methodically tailored as a scapegoat for all the miseries of medieval peasant life, was then repeatedly levied against individuals of this population in the form of gossip and overt accusations. This project of categorization, some anarchists have insisted, “is not the naming of things. It is the transformation of names into prison ships.”17

Of course, neighbors did not spontaneously turn against the women in their village overnight. Supporting Evans’ claim that the demon-worshipping stereotypes of witches were a highly organized top-down conspiracy, Federici also writes that “before neighbor accused neighbor, or entire communities were seized by a ‘panic,’ a steady indoctrination took place, with the authorities publicly expressing anxiety about the spreading of witches, and traveling from village to village in order to teach people how to recognize them.”18

All this was only possible with the mass generation of propaganda using the most advanced technology of the day – the aforementioned printing press. Of particular importance to reimagining these rebellious women as demon-worshipping baby murderers were the widely circulated copies of the Malleus Maleficarum (or “The Witch Hammer”)19 and the evocative engravings of Hans Baldung Grien.20 In his most famous work, Witches’ Sabbath, there are familiar stereotypes of witches still found in contemporary Halloween aesthetics: deformed bodies gathering around a bubbling cauldron, communing with their animal familiars (later portrayed as black cats), and flying through the air to their subversive meetings with the devil.

Of special significance to future incarnations of Halloween is this last component – the mass gathering of witches at the Sabbat. Though surely exaggerated by its enemies, some historians have speculated that the Sabbat actually may have been nocturnal gathering where thousands of peasants plotted popular revolts against the ruling classes and their enclosures of the commons.

As Italian philosopher Luisa Muraro speculates,

The fire of the [Sabbat] fades in the distance, while in the foreground there are the fires of the revolt and the pyres of repression... But to us there seems to be a connection between the peasant revolt that was being prepared and the tales of mysterious nightly gatherings... We can only assume that the peasants at night secretly met around a fire to warm up and to communicate with each other... and that those who knew guarded the secret of these forbidden meetings, by appealing to the old legend... If the witches had secrets, this may have been one.21

Given the potentially revolutionary nature of these massive gatherings, it should be no surprise that the witches who allegedly took part were considered a threat by the forces of order. Curiously, this is also the period in which a term closely resembling “Halloween” first began to appear in the English language and was used to cast a dark, devilish pall upon several Sabbats that some witches were tried for allegedly attending. Morton explains:

The choice of All Hallows’ as a major holiday for witches and devils was no doubt coerced from the accused with a political agenda in mind. [...] A spectacular witch trial took place during the reign of the Protestant king James I: in 1590, dozens of Scots were accused of having attempted to prevent James from reaching his queen-to-be, Anne of Denmark, by gathering on Halloween night and then riding the sea in sieves while creating storms by tossing live cats tied to human body parts in the water. After the infamous North Berwick Witch Trials, as they were called, Halloween was forever to be firmly associated with witches, cats, cauldrons, brooms, and the Devil.22

Mischievous Nights (c. 1600-1900 C.E.)

The unruly energies and overtly morbid aspects of Halloween have always been targeted for control... —David Skal

After this brutal erasure of an entire population of rebels and the undomesticated form of life they represented, there was a marked change in the culture surrounding Halloween in the 17th century, particularly in its endorsement of romance, parlour games, and tempered mischief. One popular hallmark of this era was a public choral performance that encouraged marriage and procreation with refrains celebrating “the wise virgins awaiting the coming of the bridegroom.” Oddly, it was these very choristers, dressed in hoods to visually represent virgin women, to whom some have traced the origins of mask-wearing and impersonation from which Halloween is now inseparable.23

These public affirmations of marriage also heralded the beginning of the seasons of Christmas and misrule, a temporary period of permitted mischief wherein urban leaders were ritually usurped from power in mock coups by impersonated sheriffs and mayors. Meanwhile in the countryside, according to one 16th century account, large groups of drunken revelers paraded the churchyards with their horses, singing and dancing “with such a confused noise that no man can heare his own voice,” and demanded contributions from their neighbors in order to continue “their heathenrie, devilrie, whoredome, drunkennesse, pride, and what not.”24

According to David J. Skal, the author of Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween, it is also within this era that the tradition of the jack-o’-lantern developed, complete with a Christian folk etymology of tempered mischief and repressive punishment:

Jack was a perennial trickster of folktales, who offended not only God but also the devil with his many pranks and transgressions. Upon his death, he was denied entrance into both heaven and hell, though the devil grudgingly tossed him a fiery coal, which Jack caught in a hollowed turnip and which would light his night-walk on earth until Judgement Day. Jack’s perpetual prank is decoying of hapless travelers into the murky mire.25

In this new era of ‘civilized’ Christianity, previous bloody wars between pagans and early Christians were replaced by relatively minor sectarian skirmishes between Protestants and Catholics – that is, until November 5th, 1605. Successfully recognized by its simple injunction to “Remember, remember the fifth of November!”, this was the day Guy Fawkes, a Catholic malcontent, was caught placing thirty-six barrels of gunpowder in a vault beneath the Protestant House of Lords, later known as the Gunpowder Plot.

Fawkes was publicly tortured and hanged as a Catholic traitor and the date of his failed attack was chosen by the Parliament as a “a holiday forever in thankfulness to our God for deliverance and detestation for the Papists.” Halloween and Guy Fawkes Day/Bonfire Night (as it came to be dually known) coexisted peacefully for over 40 years until, in 1647, Parliament banned the celebration of all festivals excepting the anti-Catholic celebration. It was then, due to their relative proximity to one another, that November 5th began to borrow some of Halloween’s mischievous traditions. Young people would spend weeks preparing for the night by going house-to-house dressed in rags and demanding firewood or money for the massive bonfire roasts of Pope effigies that would come to define the night, a tradition that some historians consider as one possible origin of trick-or-treat.26 If no firewood or money was given, it was “considered quite lawful to appropriate any old wood” from these households. This notion of justifiable theft was also present in the early 19th century British countryside, when there was a continuing war between the landed gentry and country population over the rights to hunt wild game, the Fifth of November was a time when local poachers felt they had a right to trap rabbits and shoot partridges with impunity.27

As evidence of these fires as something more subversive than mere Christian sectarian affairs, Rogers notes that some crowds not only burnt effigies of the Pope, but “any unpopular politician, clergyman, or magistrate whose actions seemed authoritarian or arbitrary.” “In subsequent decades,” he writes,

local magistrates and elites, backed by friendly and temperance societies, tried to bring these festivities to some kind of order. When the police superintendent of Market Harborough attempted to ban the burning of tar barrels on Guy Fawkes Night in 1874, he was forced to take refuge in a local hotel and had the humiliation of his own effigy burned in tar barrels the following day. According to local reports, the bands that led the protest played a popular opera song entitled, ‘We’ll run him in.’28

The first recorded use of the term Mischief Night is found in this period, used by a headmaster’s description of his school’s theatre performance that ended in “an Ode to Fun which praise[d] children’s tricks on Mischief Night in most approving terms.”29 Though originally celebrated on May 1st, Mischief Night eventually found it’s home in Great Britain on November 4th, the evening before Bonfire Night, and later, in the US, on October 30th. During this transitional time, Halloween began to reappear in the British Isles as a festival distinct from Bonfire Night, but retained some its most disorderly practices, such the targeted destruction of private property, particularly by young, working class men in Scotland and Ireland. Rogers writes:

In the traditions of mummery, revelers used such occasions to play tricks upon neighbors and occasionally to mete out rough justice to the most unpopular. Mimicking the malignant spirits who were widely believed to be abroad on Halloween, gangs of youths blocked up chimneys, rampaged cabbage patches, battered doors, unhinged gates, and unstabled horses. In nineteeth-century Cromarty, revelers even sought out lone women whom they could haze as a witch. [...] ‘If an individual happened to be disliked in the place,’ observed one Scot in 1911, ‘he was sure to suffer dreadfully on these occasions. His doors would be broken, and frequently not a cabbage left standing in the garden.’ Such was Halloween’s reputation as a night of festive retribution that in some parts of Scotland the imperatives of community justice prevailed over private property, to a point that the Kirk-session found it impossible to enforce law and order.30

It should be noted that these accounts of masculine mob attacks to deliver “community justice” to “unpopular” neighbors and “lone women” are not included as an endorsement of their obviously proto-fascist and misogynistic nature; instead, these moments usefully illustrate how, by means of witch-hunts and other more subtle forms of domestication, many women had been excluded from the sphere of rebellion and continued to be a target of low-level antagonism. Even so, it is also important not to overlook these moments’ qualities of retribution and ungovernability that will better situate the widespread vandalism of Irish-American immigrant youth and Detroit’s prolific arsonists in the coming century.

Black Halloween (1845-1945 C.E.)

The new Hallowe’en of American cities is quite unhallowed. —The Montreal Gazette, 1910

Much like the Black Plague of the 14th century, the Irish potato famine dramatically affected the course of Halloween’s evolution and world history at large. Beginning in 1845, a devastating blight began to spread across Ireland, devastating the country’s staple food crop and killing over one million Irish peasants from the resulting starvation. Over the course of the next seven years, one million more Irish left their homes, with many sailing to North America, where they soon outnumbered all other immigrant groups combined.31 It is unsurprising that this is also the context in which Halloween celebrations and revelry, long disdained by earlier waves of Puritan settlers, first began to appear in the United States. According to Lesley Pratt Bannatyne, “Wherever the Irish went – Boston, New York, Baltimore, through the Midwest to Chicago and beyond – Halloween followed along.”32

In their new homes across North America, Irish immigrant youth continued to experiment, innovate, and spread new forms of devilry during the Halloween season, creatively adapting to the idiosyncrasies of each environment. In some rural midwestern towns this meant removing farmers’ gates to free their animals, while on the east coast, it meant weaponizing the relatively abundant supply of cabbages. Lamenting that “gangs of hoodlums throng[ing] the streets” had replaced the “kindly old customs” with “the spirit of rowdyism,” William Shepard Walsh, a 19th century historian, detailed that:

Mischievous boys push the pith from the stalk, fill the cavity with tow which they set on fire, and then through the keyholes of houses of folk who have given them offence blow darts of flame a yard in length. [...] If on Halloween a farmer’s or crofter’s kail-yard still contains ungathered cabbages, the boys and girls of the neighborhood descend upon it en masse, and the entire crop is harvested in five minutes’ time and thumped against the owner’s doors, which rattle as though pounded by a thunderous tempest.33

In keeping with Halloween’s long tradition of liminality, Tad Tuleja posits that these attacks on rural households

may be seen as an attack on domestic borders. The majority of popular pranks were ‘threshhold tricks’ that assaulted, if only temporarily, ordered space. [...] Buggies, which provided cohesion to far-flung rural communities were ‘dysfunctionalized’ by being placed on barn roofs. Even the popular custom of tipping over outhouses served metonymically as an attack on the house-as-home.34

Though many of these mischievous acts against rural neighbors were treated with a wide berth of tolerance from the authorities, the tactics of urban immigrant youth soon sharpened and escalated to the alarm (and beyond the control) of fledgling American police forces, taking on a character resembling something closer to asymmetric urban warfare35 than petty mischief. In the years following the collapse of the American stock market on October 24th, 1929 (or Black Tuesday, as it came to be known), Halloween mobs specifically targeted symbols of luxury and the infrastructure of the metropolis, with a notable peak in 1933 (un-coincidentally at the height of the Great Depression) known as Black Halloween.36

According to multiple historical accounts, youth gangs from this period ripped down street signs, sawed down telephone poles, opened fire hydrants, disabled streetlights, barricaded streets with stolen gates and refuse, dragged tree stumps onto railroad tracks, overturned cars, removed manhole covers, tore up the boards of wooden sidewalks, smashed storefront windows, held shopkeepers hostage, dropped fireworks into mailboxes, unhooked poles from the tops of streetcars, spread grease over trolley car tracks, put empty barrels over church steeples, attacked the police, and burnt “almost anything they could set afire.”37

In 1945, instead of attending a sanctioned Halloween event by a local civic club, several hundred Toronto high schoolers built burning street barricades made of stolen building materials. Approaching firefighters were met with improvised anti-truck barricades made of stolen concrete blocks and mounted police were greeted with a shower of rocks. After thirteen of the Halloween rioters were eventually arrested, a mob of an estimated 7000 “youths and young girls” descended upon the police station to retrieve the teenagers, turning on fire hydrants all along the route. When they arrived they were met with tear gas and water cannons which finally forced the “howling mob” to disperse.38

Although many of these attacks were focused toward the infrastructure of the metropolis, it was “the new symbol of prosperity, the automobile [that] became the object of destruction. Revelers soaped windows, deflated tires, and at busy intersections unceremoniously ‘bounced’ cars, or rocked them from the back to the discomfort of the passengers.”39. Skal also takes note of the class antagonism that developed in this period, writing that

one report took special notice that a car overturned by a ‘mass attack’ of hoodlums was a ‘sedan of expensive make.’ The stucco of America’s social contract was likewise severely chipped by the time Franklin Roosevelt took office in 1933, and in a small way, the customs of Halloween pranking reflected more generalized anxieties about civil unrest.40

In a rare account of multiracial rebellion from this period, Skal goes on to write that

on Halloween 1934, the pranks of masked children parading through the streets of Harlem rapidly escalated from harmless flour and ash pelting to rock throwing to automobile vandalism. The police estimated that four hundred youngsters, both black and white, were involved in the various melees, which culminated with a car being heisted and rolled down a fifty-foot embankment in Riverside Park, where its tires were slashed.41

Though it would be heartwarming to imagine that these multiracial conspiracies were commonplace, it should not be surprising that not only was this rare, but actually antithetical to many other accounts from this period of unrest. In fact, three years earlier, on the Halloween night of 1931, a violent street battle developed between 400 black and white adults on the same Harlem streets.42 As these white mob attacks developed into larger race riots and widespread looting overtook the Halloween celebration of the 1934 World’s Fair in Chicago43, it was not long before the forces of order intervened to restore order to the uncivilized holiday once more.

The Taming of Halloween (1945-1960 C.E.)

Halloween affords an excellent opportunity to civilize a holiday. —The Houston Chronicle, 1955

After three decades of annual insurgency by tireless immigrant youth, it became obvious to authorities that the rebellious spirit of Halloween had to be severed from the holiday once and for all. “Although Halloween never even registered in the national debate,” Skal writes, “the many local controversies surrounding the holiday echoed much larger political themes about anarchy, order, and wealth distribution.” This “fear of a seething underclass was a strong subtext of other reform movements of the early 1930’s; film censorship campaigns for example, got especially worked up about the Halloweenish content of horror and crime movies, each genre anarchic in its own way. Such entertainments were widely viewed as demoralizing threats to public order, October 31 all year long” (48-49). “By making Halloween consumer-oriented and infantile,” Rogers adds, “civic and industrial promoters hoped to eliminate its anarchic features. By making it neighborly and familial, they strove to re-appropriate public space from the unorthodox and ruffian and restore social order to the night of 31 October” (88).

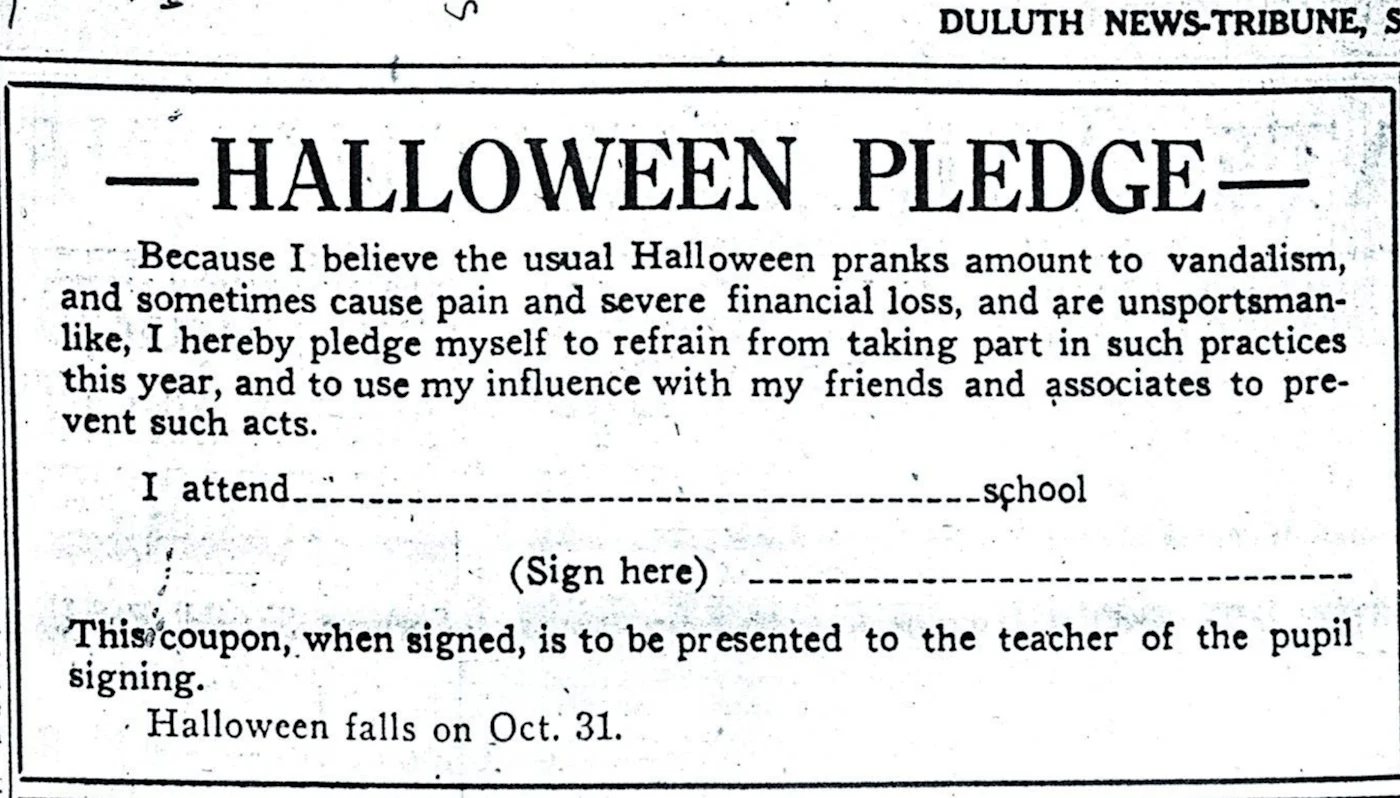

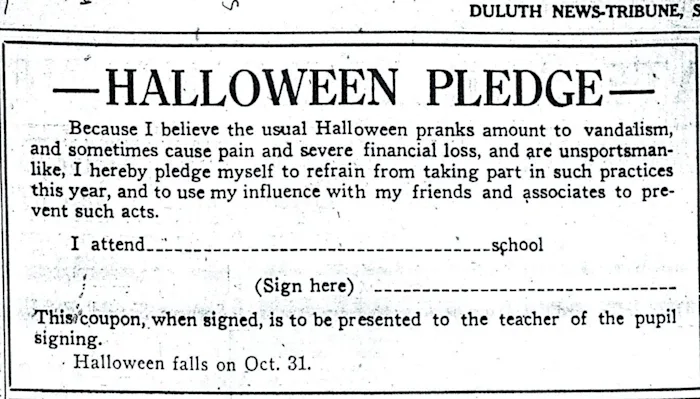

Rogers’ and Skal’s observations are illustrative because they both liken the desperate counter-revolutionary concessions of Roosevelt’s New Deal with the concerted efforts to civilize the “anarchic” holiday by police, schools administrators46, politicians47, churches, and civil groups. While these new efforts certainly utilized strategies from previous centuries – erasure via film censorship, romance via costume balls, parlour games via church lock-ins, etc – there was also a newly available option in the post-Depression era now presented itself for exploitation: consumption.

Though there is evidence that some Halloween rebels were being bought off with candy as early as 192048, it was not until after the Halloween unrest of the mid-1930’s and the post-WW2 production boom that trick-or-treating was explicitly promoted as a strategy for restoring order to the reviled holiday. One of the first national mentions of the term “trick-or-treat” was found in a 1939 article entitled A Victim of the Window Soaping Brigade?, which specifically names the practice as “a method of subverting rowdy pranking.”49

Though the precise origins of the tradition itself are disputed by some historians, many agree that it at least partially arose from Depression-era “house-to-house parties” that some neighbors would cooperatively host on Halloween to save money. “Whatever its specific sources, inspirations, or influences,” Skal writes, trick-or-treating “became widely known and adopted as a distinct property-protection strategy during the late Depression.”

However, he clarifies,

it is the postwar years that are generally regarded as the glorious heyday of trick-or-treating. Like the the consumer economy, Halloween itself grew by leaps and bounds. Major candy companies like Curtiss and Brach, no longer constrained by sugar rationing, launched national advertising campaigns specifically aimed at Halloween. [...] The begging ritual was modeled for millions of youngsters in the early fifties by Donald Duck’s nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie in Disney’s animated cartoon ‘Trick or Treat,’ accompanied by a catchy, reinforcing song of the same title.50

In addition to promoting trick-or-treating as an explicit alternative to vandalism, Rogers also cites this specific Donald Duck cartoon as a propaganda piece critical to the “taming of Halloween,” writing that “rather than experience real-life shenanigans, children could find them in a Walt Disney cartoon.” By the late 1950’s the antagonism that had come to previously define October 31st had been almost completely severed from the holiday and supplanted with a totally naturalized ethic of consumption, whether in the form of candy or experiences. This apparently was so effective in Los Angeles that one police sergeant publicly expressed his confusion about the disappearance of teenage rebels after a oddly peaceful Halloween there in 1959.51 In the same year, sociologist Gregory Stone penned an essay entitled Halloween and the Mass Child that considered trick-or-treat “a rehearsal for consumership without a rationale.” Though there existed a brief period where the stinginess of a neighbor would be met with the retribution of a “trick” (typically in the form of petty vandalism), Stone noted that by the late 1950’s this practice had been largely forgotten and these children “didn’t know why they were filling their shopping bags.” After interviewing eighteen trick-or-treaters who visited his home in Missouri, he melodramatically asked:

Was the choice proffered by these eighteen urchins when they wined or muttered, ‘Trick or treat?’ or stood mutely at my threshold, a choice between production and consumption? Was being offered the opportunity to decide for these youngsters the ultimate direction they should take later in life by casting them in the role of producer or consumer? Was I located at some vortex of fate so that my very act could set the destiny of the future? Was there a choice at all? No. In each case, I asked, ‘Suppose I said Trick. What would you do?’ Fifteen of the eighteen (83.3%) answered, ‘I don’t know.’52

This copy-of-a-copy without an original source, as theorist Jean Baudrillard once conceived of simulacra, proved effective in both erasing Halloween’s rebellious legacy, while also exceptionalizing a singular moment of hyper-consumption in order to obscure its sudden and dramatic pervasiveness throughout the rest of American society. Baudrillard expands upon this concept to explain the essence of Disneyland, which, he argues,

exists in order to hide that it is the ‘real’ country, all of ‘real’ America that is Disneyland (a bit like prisons are there to hide that it is the social in its entirety, in its banal omnipresence, that is carceral). Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, whereas all of Los Angeles and the America that surrounds it are no longer real, but belong to the hyperreal order and to the order of simulation.53

Of course, these repressive strategies could not be applied uniformly across the entire continent, especially outside of the metropolis. In some places the disorder previously associated with Halloween was simply displaced to October 30th.54 As one man proudly remarked of his boyhood in Hoboken, New Jersey, “there was only mischief. The adult world could not buy us off with candy or shiny pennies. They didn’t even try.”55 In these small pockets of lingering antagonism, particularly in the newly developed suburbs of the period, the vandalism took on a decidedly less revolutionary character, reverting to a previous form of pranks that targeted “unpopular” or stingy neighbors by smashing their pumpkins or stealing their gate. And because of their relative isolation to one another, many of the areas developed hyper-localized terms for their own destructive sports, like Vermont’s Cabbage Night, Montreal’s Mat Night, upstate New York’s Gate Night, New Jersey’s Mischief Night, and later Detroit’s infamous Devil’s Night.56

The Demonization of Halloween (1967-present)

As you are most likely aware, Halloween is not the same anymore. —The Montreal Gazette, 1982

Whatever happens in America happens here first. Detroit is like a laboratory for the rest of the country. —Barbara Rose Collins

On July 23rd, 1967, after the police raided a party for two returning Vietnam GIs at an illegal speakeasy on the Near West Side of Detroit, crowds of mostly Black residents gathered outside and began throwing bottles and stones in retaliation. The police were forced to retreat and the remaining crowd seized the opportunity to pillage a nearby clothing store and quickly escalated into full-scale looting throughout the entire neighborhood. Some witnesses would later describe this moment as a “carnival atmosphere” of multiracial looting, in which the police were totally outnumbered and were forced to watch this “gleefulness in throwing stuff and getting stuff out of buildings” from a careful distance.57 By the next afternoon, the first fire had been set at a nearby grocery store and a small mob formed to block a firetruck from putting out the flames. Though the local media initially refused to report on the unrest for fear of it spreading to other parts of the city, the unavoidable smoke of a burning Detroit soon began to fill the city’s skyline.58

Fires and looting generalized across the entire city over the next 24 hours, targeting both Black and white-owned businesses and resulted in 38 handguns and 2,498 rifles being expropriated by the rebellious population.59 In response, President Johnson was forced to invoke the Insurrection Act of 1807, which authorized the use of federal troops to put down an insurrection against the U.S. Government. Beginning at 1:30am on July 25th, over 8,000 Michigan Army National Guardsman and 4,700 U.S. Army Paratroopers descended upon the city to put down the uprising. In the following three days, countless horrors of brutality, sexual assault, and targeted assassination were visited upon those who continued to fight against the forces of order.60

By July 28th, after the last fire had been set, troops began to slowly withdraw from the city and authorities began to survey the damage. All told, the five days between July 23 and 28 resulted in 2,509 stores being looted or burned, 7,200 arrests, 1,189 injuries, and 43 casualties – 33 of whom were Black and 27 of whom were killed by state forces.61 Unlike the 1943 Detroit race riot, however, many observers noted a high participation of white residents in the looting of stores, setting fires, and sniping cops, which raised questions about whether the uprising could be simply categorized as a ‘race riot.’ The Great Rebellion, as it came to be known instead, set off a wave of unrest that would continue to spread to over two dozen cities and circle back to Detroit the following year after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.62

It is following this period of social upheaval and counterinsurgency in North American cities that a diffuse anxiety over ‘inner city issues’ developed within some of the white population, which led to a mass exodus to the suburban peripheries, later known as white flight. In these shiny new refugee camps for the white middle class, an alienating fear of the Other lingered and would prove to be a death knell for trick-or-treating, one of their children’s last remaining sources of autonomy and camaraderie outside the nuclear family unit.

Given trick or treat’s almost universal suburban popularity,its emphasis on representation of outsiders, and the way it empowered its participants, it was perhaps inevitable that trick or treat was about to experience a backlash. Adults, it seemed, were unwilling to grant their children that power after all. In 1964 a New York housewife named Helen Pfeil was upset at the number of trick or treaters whom she thought were too old to be demanding candy, and handed them packages of dog biscuits, poisonous ant buttons, and steel wool. Within three years the urban legend of children being given apples with hidden razor blades surfaced, and parents began to worry about Halloween.63

These “tales of Halloween sadism,” Rogers explains,

were measured against the vision of a stable, congenital decade of trick-or-treating in the 1950’s. This was a decade of Cold War politics and Red scares. Yet beyond the zone of leftist agitation, it was also a decade of relative social peace, of continuing baby boom, of consumer affluence and suburban development. The 1960’s and 1970’s, however, posed new challenges to the social and political fabric of the United States. This was the era of civil rights agitation, of urban ghetto riots, of student and antiwar protest, of youth countercultures, of feminism and gay liberation, of Watergate. In the South, African-Americans defeated Jim Crow, but in the North they faced de facto resegregation as whites fled to the suburbs in the wake of rioting in Watts, Newark, and Detroit.64

Though only two deaths (both of which were later attributed to family members) and a small number of injuries were reported over two decades of the Halloween sadism scare65, the media was quick to portray the holiday as rife with satanic overtones and stranger danger which already weighed heavy on the minds of many WASP surburbanites. “Somehow Halloween no longer had anything to do with extending latitude or license to children,” Skal writes, “it was more about parental control, a ceremonial reassurance of the family’s integrity and stability in an uncertain world.” Kier-La Janisse elaborates further in her introduction to Satanic Panic: Pop Culture Paranoia in the 1980s:

In the early 1970’s, with the Vietnam War in full swing amidst a rising tide of dissent and the bloodbaths of Altamont and Cielo Drive officially bringing a disillusioned end to the Age of Aquarius, the Baby Boomers looked to unconventional corners of religious experiences for answers. Alternative religions flourished, from the Jesus People movement and more radical end-times counterparts to neo-paganism, suburban witchcraft and of course, Satanism. [...] By the time the 1980’s rolled around, people had already been groomed to believe that there could be occultists living next door. And after a decade that saw the rise of “latch-key kids” who were left to their own devices while often-absent parents sought to work out their own issues through a variety of spiritual and experimental therapeutic methods, concern turned again to the children. While the publication of Michelle Remembers in 1980 spawned renewed international dialogue about horrific child abuse behind closed doors, the double-whammy of the highly-publicized disappearance of Adam Walsh in 1981 (serial killer Ottis Toole later confessed to his murder) and the initial allegations of the famed McMartin preschool trial in 1983 effectively put an end to the carefree days of Gen-X kids. No more walking home from school alone. No more playing outside until the streetlights came on. No more Jarts.66

Following this pervasive moral panic, many parents and civic groups began to mobilize with the goal of extracting ‘the youth’ from Halloween’s unsurveilled darkness once and for all. In just a few years time, thousands of alternatives to trick-or-treating were organized at shopping malls, museums, zoos, schools, spook houses, and community centers across the continent, while some hospitals continued to reinforce the paranoia of Halloween sadism by offering to X-ray the die-hard trick-or-treaters’ candy for dangerous metal objects.67 With this deeply paranoid suburban populace already highly attuned to the sinister and satanic overtones of the holiday and an urban core on the brink of implosion, it was only a matter of time before the Devil himself, long since banished to mockable impotence and childhood costumes, would come to symbolically possess Halloween once more.

Within five years of the The Great Rebellion, the composition of Detroit’s urban population had completely changed, producing a majority Black inner city ringed by a periphery of hostile white suburbs. “In the aftermath of the riot,” Ze’ev Chafets explains in his once controversial 1990 book Devil’s Night: And Other True Tales of Detroit, “Detroit became the national capital of disingenuous surprise. People suddenly discovered what should have been obvious – that beyond the glittering downtown, the leafy neighborhoods, the whirring computers, there was another city: poor, black, and angry,” that “seethes with the resentments of postcolonial Africa.”68

Within this new context of manufactured stranger danger, “Satanic Panic,” urban abandonment, economic stagnation, generalized poverty, anti-Blackness, and Black rage, that the rebellious spirit of Halloween once again returned to animate and rechristen the holiday’s eve: Devil’s Night, “the day Detroit sets itself on fire.”69

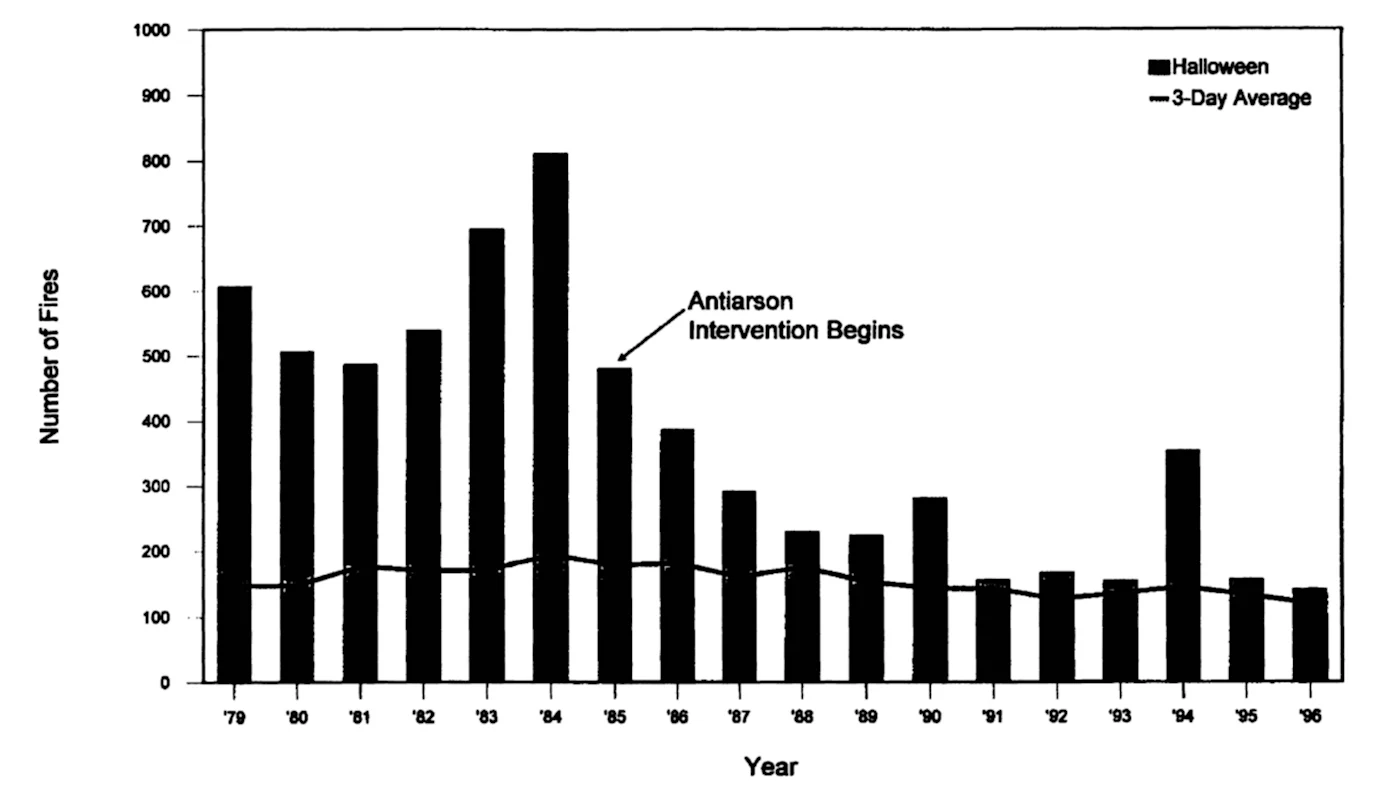

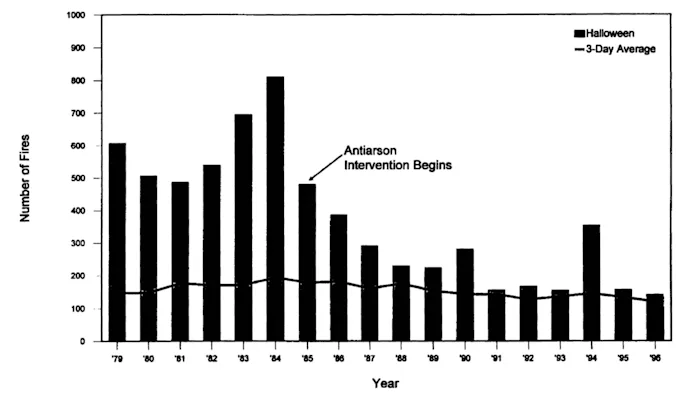

Although 1983 is widely recognized as the unofficial beginning of Devil’s Night because of its dramatic increase in dumpster and brush fires, there is evidence to suggest that there was a already a low-level insurgency associated with Halloween dating back to at least 1979 and, arguably, to 1967 itself. Only in 1984 (probably due to the combination of widespread media hype of the 1983 arsons and the World Series victory by the Detroit Tigers on October 31st), was there a marked increase in structure fires, which prompted a response from the authorities. With over 297 arsons on October 30th alone, 1984’s Halloween season set the high water mark for destruction with “the worst fire scenes I’ve seen since the riots of 1967,” according to a former Detroit Fire Department chief.70 His statement is notable because within it is a glimpse of authorities’ conceptual framework for viewing Devil’s Night – not as an isolated incident, but rather as an aftershock of The Great Rebellion that rivaled its destruction and, therefore, could be eligible for the same levels of counterinsurgency.

Just as the witch, whose supernatural identity and proximity to the Devil was manufactured to scapegoat and exterminate an unwanted heterogenous population, the image of the Abrahamic Satan himself – whose name is derived from the Hebrew word for “adversary” and the Arabic word for “astray” – was revived to quite literally demonize the rebellious Black youth of Detroit.71 By popularizing this narrative, the city’s authorities and media outlets were able to harness the suburbs’ pre-existing racist hostility towards the inner city’s new Black majority and weaponize it against a singular antagonist: the devilish arsonist who was damning their great city to hell. In the introduction to his book, Chafets describes how this pervasive sentiment among some of the city’s former white residents generated the odd spectator sport of “fire watching” on Devil’s Night:

At every story, people gawked at the flames and passed around bottles of whiskey and thermos caps of steaming coffee. The suburbanites talked with bittersweet nostalgia in Detroit, pointed to childhood sites now sunk in decrepitude and shook their heads. The message was tacit but unmistakable – Look what they’re doing to our city.72

After two back-to-back years of record-setting arson sprees, Patricia Anstett, a journalist for the Detroit Free Press, interviewed 24 city experts and “community leaders” about what circumstances they believed were producing these fires and placed the results into seven broad categories: Professional arsonists, Unemployment, Pent-up feelings of urban youths, Insurance fraud, Attention placed on the event, Lack of leadership in the community, and Large numbers of abandoned buildings.

Whatever the reason, another Detroit Free Press article poetically concluded, “contemplating the roots of such outbursts – the feelings of hopelessness and despair, boredom with things as they are, defiance of those charged with making it better – provides little comfort as fire sirens scream in the night.” After 1984, this influential city newspaper notably avoided any sort of sociological analysis, instead favoring a “law-and-order approach to Halloween Eve arson and crime, including gun control, aggressive prosecution, and more jail cells.”73 With this endorsement to act decisively, Mayor Coleman Young then created a “Devil’s Night Task Force” with the stated goals of “reduced arson, raised community awareness, and increased involvement in the fight against arson.” The task force first began by collecting logistical data from the Detroit Fire Incident Reporting System (DFIRS) to geographically map high-risk areas and create timelines for when fires had previously occurred – in essence, to forecast arson. Each spring, appointees from the mayor’s office, Detroit Neighborhood City Halls, city departments (public health, fire, police, youth, public lighting, law, recreation, information technology, planning, among others), community organizations, churches, public schools, and the private sector would convene to begin creating implementation plans based on these forecasts.74

With these plans in hand, fire and police officials from each neighborhood collaborated with neighborhood snitches and influential clergy to create “decentralized action plans” for an eight point, city-wide strategy: Deployment of Public Safety Personnel via the mobilization of all available police, firefighters, and helicopters; The Elimination of Arson Targets via towing abandoned cars, removing tires from dumping sites, and demolishing thousands of vacant homes and buildings; Volunteer Training via orientations for Adopt-A-House volunteers who wanted to guard abandoned buildings or neighborhood patrols who wanted to seek out arsonists on foot; Media and Communications via aggressive PR campaigns to convey “the dangers of arson;” Activities for Children and Teenagers via church and city-sponsored movie marathons, dances, carnivals, etc.; Youth Curfew via a strict 6 P.M. curfew for those under 18, whose violators would face expedited processing at temporary nighttime courtrooms; and Prohibition on the Sale of Fuel by means of criminalizing the sale of dispensing of gasoline into portable containers.

Each of these eight points – and many of the aforementioned strategies used against previous generations of Halloween rebels – are strikingly similar to counterinsurgency strategies lifted from Army Field Manual on Counterinsurgency and British brigadier Frank Kitson’s writings on repressing anti-colonial movements in Kenya, Cypress, and Northern Ireland.

Of critical importance to the success of these strategies, Kristian Williams writes in his essay The Other Side of COIN, was “monopolizing the use of force” and establishing total legitimacy in doing so, which the Army field manual asserts is “the main objective.”76 This mentality was demonstrated in the City of Detroit’s contradictory strategy of both guarding and demolishing abandoned buildings – a clearly desperate attempt to re-establish control over a populace that had subverted its monopoly on destruction. As part of maintaining their already fragile legitimacy, however, the outnumbered police could not simply activate the National Guard again to protect these buildings; instead, they had to militarize their own operations and source their foot soldiers and snitches from the few remaining loyal strata of the local population, notably the clergy and business owners.

This type of community policing, The Rand Corporation writes,

is centered on a broad concept of problem solving by law enforcement officers working in an area that is well-defined and limited in scale, with sensitivity to geographic, ethnic, and other boundaries. Patrol officers form a bond of trust with local residents, who get to know them as more than a uniform. The police work with local groups, businesses, churches, and the like to address the concerns and problems of the neighborhood. Pacification is simply an expansion of this concept to include greater development and security assistance.77

When viewed through Williams’ simple and elegant equation, the strategies that implemented by Young’s Devil’s Night Task Force quickly reveal their obvious and undeniable nature:

Community Policing + Militarization = Counterinsurgency

Between 1985 and 1996, largely by means of these counterinsurgency strategies and bloody anti-gang initiatives, authorities were able to claim a victory of reducing Halloween-time arson to a level not seen in the city since the 1970’s. Though some may be tempted to conclude that this was also the moment when the rebellious spirit of Halloween was finally killed, to do so would deny the near-constant low-intensity smoldering that remained in the city and would later spread to other cities like Flint, Camden, and Cincinnati in the early 1990s. In 1994, after the new mayor of Detroit pompously declared the death of Devil’s Night and mobilized a significantly smaller number of citizen patrols, the number of arsons dramatically rose, forcing him to mobilize an army of 30,000 “Angel’s Night” volunteers the following October.78

Given this persistent obligation to douse its embers, this was clearly not the death of the Halloween spirit, but rather its temporary smothering.

The historical fact that bonfires have remained central to Halloween’s character for over two millennia speaks to something deeply desirable about gathering communally and burning away the old world together – a practice now rapidly spreading across the rest of the calendar. As the rare moments of social peace between upheavals in the U.S. become ever shorter and the fire of the Sabbat that once frequented Detroit sweeps through Ferguson, Baltimore, Milwaukee, and Charlotte, perhaps the ungovernable spirit of Halloween will not only return as a discrete, exceptionary moment in October, but, in the words of an old anarchist revolutionary, a holiday without beginning or end.

October 31, all year round.

First published by Mask Magazine, October 2015. Revised and expanded by the author, October 2017.

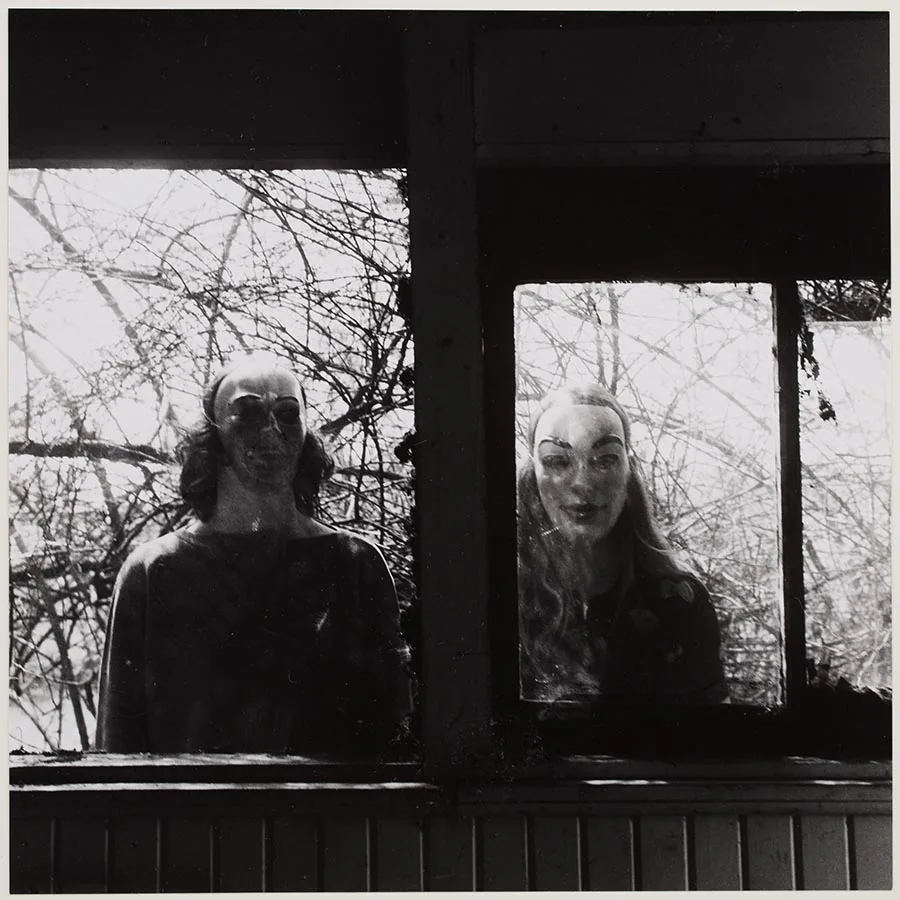

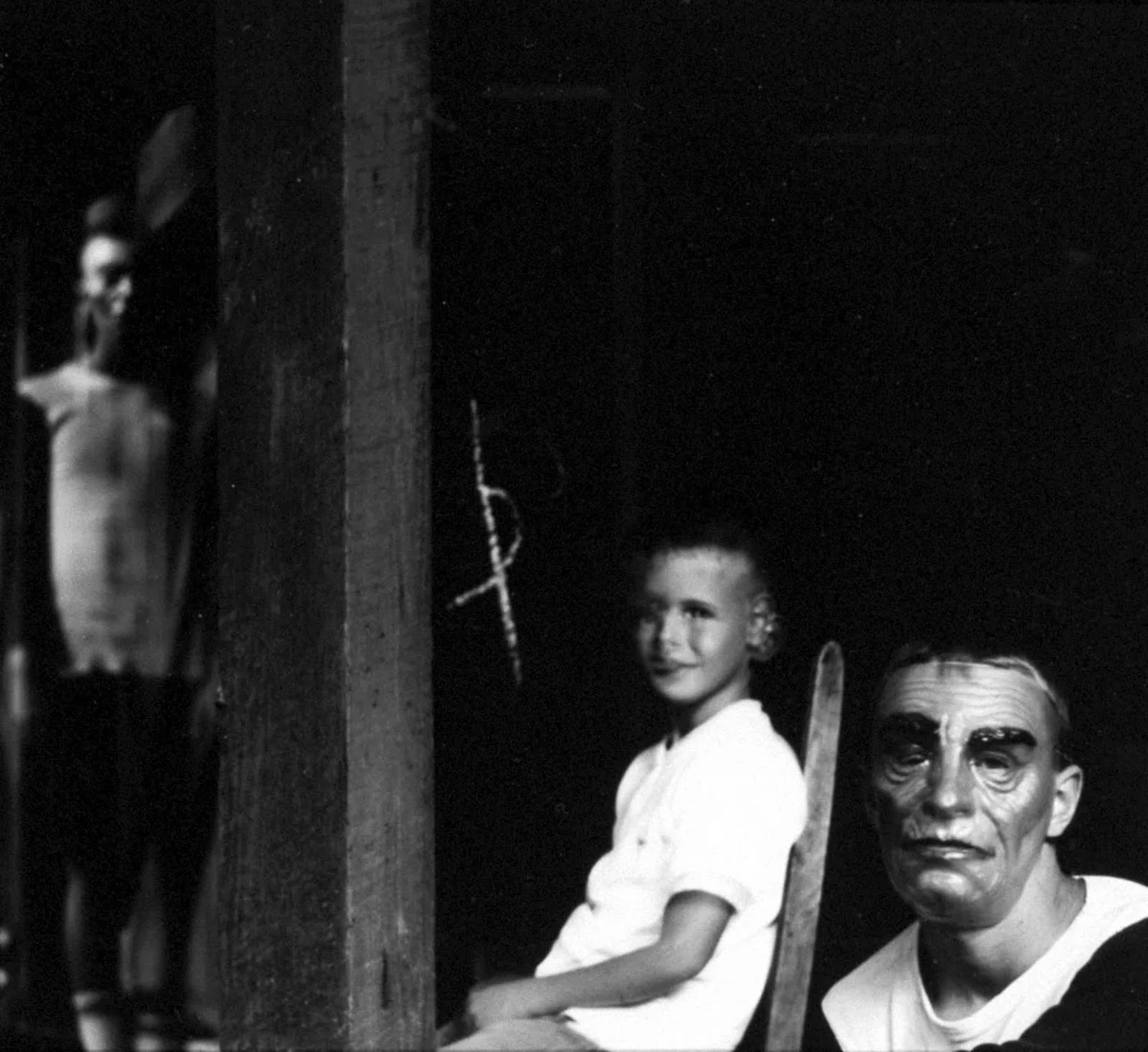

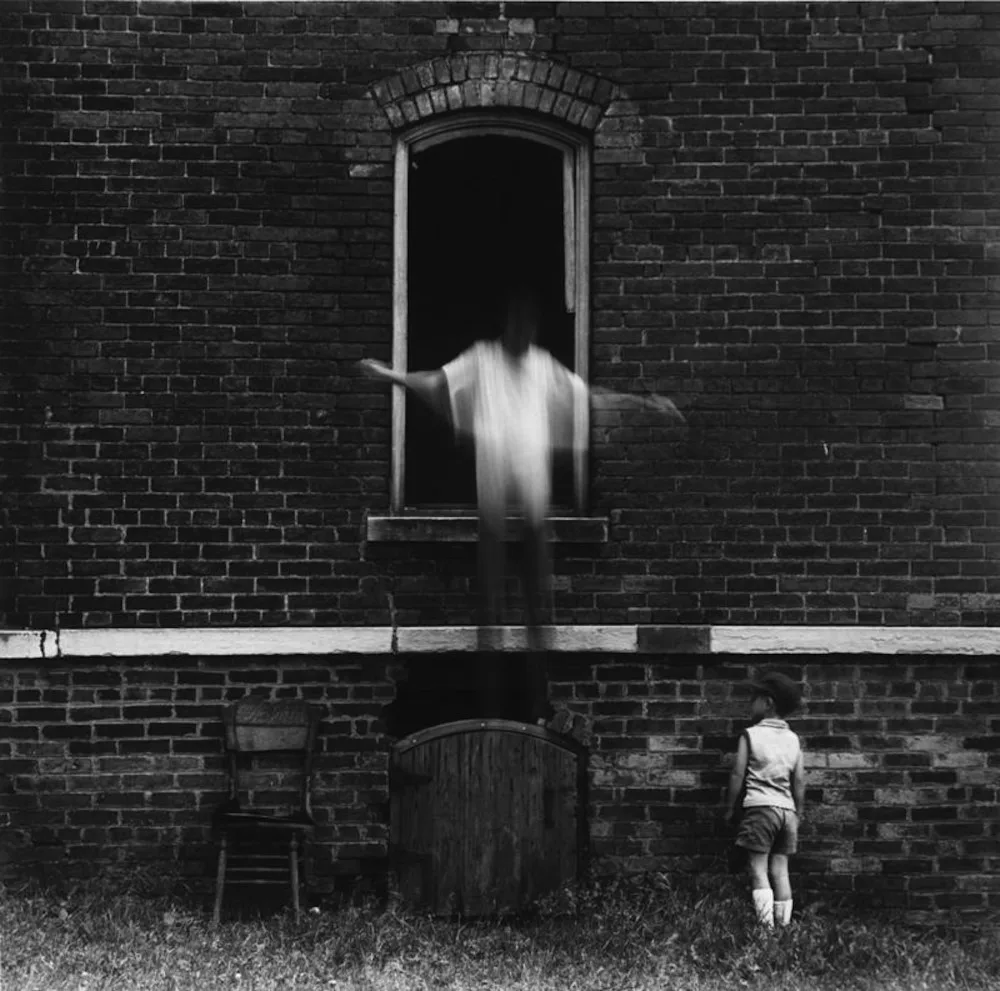

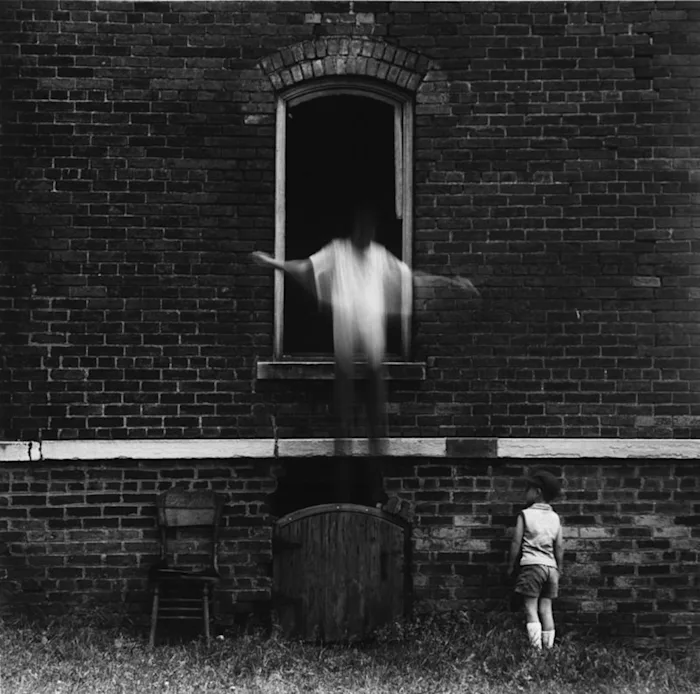

Images: Ralph Eugene Meatyard

A print version is available here.

Notes

1. Nicholas Rogers, Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night, Oxford University Press, 2002, 11.↰

2. Lisa Morton, Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween, Reaktion Books, 2012, 12.↰

3. Peter Ellis, The Celtic Revolution: A Study in Anti-imperialism, Y Lolfa, 1985, 12.↰

4. Morton, Trick or Treat, 14.↰

5. Rogers, Halloween, 12.↰

6. Barry Cunliffe, The Celts: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2003, 137.↰

7. Morton, Trick or Treat, 14–15.↰

8. Ibid, 17.↰

9. Ibid, 18–19.↰

10. Ibid, 21.↰

11. Arthur Evans, Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture, Fag Rag Books, 1978, 104.↰

12. Morton, Trick or Treat, 23.↰

13. According to Evans, the early Church “turned homosexuality into heresy” and began to collapse the two identities so that to call someone a heretic was to call them a homosexual, and vice versa. “Because of the methods of the Inquisition,” he writes “great numbers of Lesbians and Gay men must have lost their lives.” Evans, Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture, 101. We can also assume that the many individuals who today might have self-identified as transgender or gender-variant were likely also targeted for extermination. Besides the popular story of Joan of Arc, there is unfortunately very little other research into this history and, therefore, the only reference point for this period is Federici’s witch-as-ciswoman.↰

14. Morton, Trick or Treat, 21–22. See also Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch, Autonomedia, 2004, 179–184.↰

15. Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 180.↰

16. Carole Nagengast, “Violence, Terror, and the Crisis of the State,” Annual Review ofAnthropology, Vol. 23, 1994, 122.↰

17. Lev Zlodey & Jason Radegas, Here...at the Center of the World in Revolt, Little Black Cart, 2014, 220.↰

18. Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 166.↰

19. This text, which was published with the blessing of Pope Innocent VIII, was intended as a handbook for both recognizing and, as the title suggests, obliterating the witch. Referring to the now widely-recognized Halloween icon of the flying witch, the authors offer a conveniently damning explanation for their abilities: that they utilized an ointment which “they make at the devil’s instruction from the limbs of children, particularly of those whom they have killed before baptism, and anoint with it a chair or broomstick; whereupon they are immediately carried up into the air...” David Skal, Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween, Bloomsbury, 2002, 67.↰

20. Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 166–168.↰

21. Luisa Muraro, La Signora del Gioco: Episodi di cacda alle streghe, Feltrinelli Editore, 1977, 46–47.↰

22. Morton, Trick or Treat, 22.↰

23. Rogers, Halloween, 25.↰

24. Phillip Stubbs, The Anatomie of Abuses, 1583.↰

25. Skal, Death Makes a Holiday, 31.↰

26. Morton, Trick or Treat, 24–26.↰

27. Rogers, Halloween, 35.↰

28. Ibid, 17.↰

29. Martin Wainwright, “Traditionalist pranksters prepare for mayhem of Mischief Night,” The Guardian, online here: https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2008/nov/02/2↰

30. Rogers, Halloween, 42.↰

31. Morton, Trick or Treat, 64–65.↰

32. Lesley Pratt Bannatyne, Halloween: An American Holiday, an American History, Pelican Publishing Company, 1990, 10.↰

33. Skal, Death Makes a Holiday, 33.↰

34. Tad Tuleja, “Trick or Treat: Pre-Texts and Contexts,” Halloween and other Festivals of Life and Death, ed. Jack Santino, University of Tennessee Press, 1994, 87.↰

35. In British oral historian Paul Thompson’s 1975 essay, “The War with Adults,” he elaborates further on the antagonism that existed in early 20th century British youth gang culture: “It was on the street, rather than in the home, that children first learnt to resist adults, for here they formed a larger group themselves and were much less hampered by prior social bonds with their adult enemies. The police set the tone of relationships in working-class districts with a molestation which was sometimes meanly effective (as when they knifed the footballs which they captured), sometimes a game in itself.” He goes on to retell a Mischief Night story of a boy from Leeds: “Oh yes, we were little devils. At one time we took an interest in chemistry. Chemistry consisted of making explosives, as far as I remember. Potassium chlorate was a very good one which we used to make little piles of and drop bricks on which created loud explosions and all the tradesmen’s horses in the vicinity immediately bolted. That was great fun. We also – the catapult craze came along and our targets were usually the insulators on telegraph poles. If you broke an insulator on a telegraph pole that was a good score ... In Yorkshire ... the day before Bonfire Night was called Mischief Night, and Mischief Night we always took a delight in sewing up one’s sisters and brother’s pyjamas, making apple pie beds, plastering treacle on neighbours door handles, ringing the bell and running away, tying up gates, and things of this sort. This was always accepted as part of the fun on Mischief Night. And of course, often neighbours lay in wait for one and one got boxed ears, but that was part of the hazards of the fun.” Paul Thompson, “The War with Adults,” Oral History Vol. 2, No. 2, Family History Issue, 1975, 4–5.↰

36. Morton, Trick or Treat, 75.↰

37. Ibid. See also Rogers, Halloween, 83 and Skal, Death Makes a Holiday, 47–48.↰

38. Morton, Trick or Treat, 83.↰

39. Rogers, Halloween, 79. ↰

40. Skal, Death Makes a Holiday, 47.↰

41. Ibid, 48.↰

42. Rogers, Halloween, 82.↰

43. “When the Chicago World’s Fair of 1934 ended on 31 October, the authorities should have predicted trouble. At midnight, some 300,000 revelers, some of them masked at witches, took complete control of 32 miles of streets and concessions, ‘drank everything in sight except Lake Michigan,’ and rifled everything ‘moveable as souvenirs.’ At the horticultural building, for example, ‘thrifty house- wives’ were reported taking home $200 plants as admission souvenirs. Hundreds of police reserves were brought in to clear the crowds from the fairground, but crowds were still pouring in as late as 3 A.M.” Ibid.↰

44. Skal, Death Makes a Holiday, 48–49.↰

45. Rogers, Halloween, 88.↰

46. In one particularly humorous episode, the Associated Press reprinted a letter from a Rochester school superintendent which desperately attempted to re-cast Halloween unrest as ‘no longer fun’ and, furthermore, a threat to national security: “Letting the air out of tires isn’t fun any more. It’s sabotage. Soaping windshields isn’t fun this year. Your government needs soaps and greases for the war. Carting away property isn’t fun this year. You may be taking something intended for scrap, or something that can’t be replaced because of war shortages. Even ringing doorbells has lost its appeal because it may mean disturbing the sleep of a tired war worker who needs his rest.” Skal, Death Makes a Holiday, 55.↰

47. “In 1950, Judiciary Committee of the U.S. Senate recommended to President Harry Truman that Halloween should be transformed into ‘Youth Honor Day.’ The resolution was intended ‘to give nation- al recognition to the efforts of organizations throughout the country which have attempted to direct the activities of young people into less-destructive channels on Halloween each year.’ According to the plan, youngsters would receive pledge cards at school urging them not to destroy property on the holidays. Once this pledge was given, they would receive a ticket to a Halloween dance or party. [...] This sort of approach had also been recommended by the Toronto authorities in the aftermath of the Kew Beach riot of 1945. ‘There is much that can be done in the way of community enterprises which will provide a worthy outlet for the exuberance of youth,’ opined the Globe. [...] Like other newspapers, it was relieved to report that Halloween rioting of Toronto’s East End in 1945 was succeeded in 1946 by a popular party at the Malvern Collegiate high school that attracted thousands of teenagers. It was in the city’s best interests that Halloween became more of a dating ritual than an occasion for street rowdiness.” Rogers, Halloween, 85.↰

48. “Packaging for Ze Jumbo Jelly Beans, manufactured in Portland, Oregon, contained the prominent message to STOP HALLOWEEN PRANKSTERS.” Skal, Death Makes a Holiday, 44.↰

49. Morton, Trick or Treat, 79.↰

50. Skal, Death Makes a Holiday, 54–55.↰

51. Rogers, Halloween, 90.↰

52. Skal, Death Makes a Holiday, 56.↰

53. Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, University of Michigan Press, 1994, 12.↰

54. Morton, Trick or Treat, 87.↰

55. Rogers, Halloween, 86.↰

56. Morton, Trick or Treat, 87–88.↰

57. Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967, University of Michigan Press, 1989, 165.↰

58. Herb Colling, Turning Points: The Detroit Riot of 1967, A Canadian Perspective, Natural Heritage Books, 2003, 42.↰

59. Kenneth Stahl, “Snipers,” Detroit’s Great Rebellion, online here: http://www.de- troits-great-rebellion.com/Snipers.html↰

60. Ronald Young, “Detroit Riots (1967),” Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia, ed. Steven L. Danver, ABC-CLIO, 2010, 989–990.↰

61. Ibid, 990.↰

62. Joshua Clover, Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings, Verso, 2016, 124.↰

63. Morton, Trick or Treat, 90.↰

64. Rogers, Halloween, 94.↰

65. Ibid, 92-93.↰

66. Kier-La Janisse, “Introduction: Could it be...Satan?” Satanic Panic: Pop-Cultural Paranoia in the 1980s, ed. Kier-La Janisse & Paul Corupe, Spectacular Optical Publications, 2015, 14-15.↰

67. Morton, Trick or Treat, 91.↰

68. Ze’ev Chafets, Devil’s Night: And Other True Tales of Detroit, Vintage Books, 1990, 22.↰

69. Toni Moceri, Devil’s Night, Shrinking Cities, 2003, 71.↰

70. Ibid.↰

71. Federici offers a useful historical context for this demonization of Blackness in the United States: “Witch-hunting and charges of devil-worshipping were brought to the Americas to break the resistance of the local populations, justifying colonialism and the slave trade in the eyes of the world. [...] The common fate of Europe’s witches and Europe’s colonial subjects is further demonstrated by the growing exchange, in the course of the 17th century, between the ideology of witchcraft and the racist ideology that developed on the soil of the Conquest and the slave trade. The Devil was portrayed as a black man and black people were increasingly treated like devils, so that ‘devil worship and diabolical interventions [became] the most widely reported aspects of the non-European societies that slave traders encountered.’” Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 197. This racist legacy also continues in the present moment, notably in the murder of Mike Brown by police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri. According to Wilson’s testimony, he shot the 18 year old Black boy once, who then took on an “intense, aggressive face. The only way I can describe it, it looks like a demon, that’s how angry he looked.” He then shot Mike three more times, with one shot to the head. He told the jurors that he remembered seeing the top of Brown’s head through the site of the gun and pulling the trigger: “And then when it went into him, the demeanor on his face went blank – the aggression was gone, I mean, I knew he stopped, the threat was stopped.” Amy Davidson, “Darren Wilson’s Demon,” The New Yorker, online here: http://www. newyorker.com/news/amy-davidson/demon-ferguson-darren-wilson-fear-black-man↰

72. Chafets, Devil’s Night, 5.↰

73. Skal, Death Makes a Holiday, 151.↰

74. Barbara J Maciak, “Preventing Halloween Arson in an Urban Setting: A Model for Multisectoral Planning and Community Participation,” Health Education and Behavior, Vol. 25 No. 2, April 1998, 198–199.↰

75. Ibid, 201-203.↰

76. Kristian Williams, “The Other Side of COIN: Counterinsurgency and Community Policing,” Interface: A Journal for and about Social Movements, Vol. 3, May 2011, 84.↰

77. Ibid, 91.↰

78. Skal, Death Makes a Holiday, 152.↰