Artificial Intelligence, or the End of Technics

Gabriel Azaïs

While much criticism of artificial intelligence still circles around fantasies of robot competitors rising up against man, the following essay aims to turn the problem around: the real concern with AI research, Azaïs argues, lies not in humanlike robots but in the impoverished image of humanity to which it condemns us by its reduction of human intelligence to the level of technics or calculation. By breaking down and translating human reasoning, communication, and decision into the computerized language of tasks, computation does not replace man with the machine but ensures that man “behaves and acts like a machine, that society as a whole technicizes through a subtle play, by turns, of normalization and imitation.”

Taking his cue from French philosopher Jacques Ellul, Azaïs argues that such ostensibly scientific aspects of “AI technology” are inextricable from a Promethean myth that is not only necessary to its functioning, but also works to conceal the alienation it itself produces. Fictions such as “artificial general intelligence” and the “singularity” not only bind together an otherwise motley jumble of techniques and applications with no connection or foundation, they also reinforce a magical belief in the omnipotence of technology. This sacralized image of technics, embodied in the paradoxical quest to produce an autonomous and all-powerful demiurgic creature, inverts and distorts the truth of the technological system on which it relies. In reality, the efficacy of AI depends precisely on the integration of human life into a technicized social system, a “cybernetic utopia” in which human decision, right, and law have been replaced by the technical fact of algorithmic governmentality. Millenarian myths about the “future of AI” are therefore ultimately nothing but mystified personifications of the oppressive heteronomy of our present condition. In them, the very source of our alienation — a technical system that invisibilizes, denatures, and destroys all that eludes its single-minded rationality — is transformed into a supernatural sci-fi fantasy whose “autonomy” is merely an inverted reflection of our current passivity.

As techno-feudalist dystopias continue to engulf the American ruling class, the effort to combat them cannot content itself with a narrowly political opposition, but must simultaneously incorporate strategies to desacralize technics. The profanation of techniques, as Ellul and Azaïs remind us, forms a precondition for any effort at genuine liberation.

Other languages: Français, Español

Technology has in itself a certain number of consequences, it represents a certain structure, certain demands, and it brings about certain modifications of man and society, which force themselves upon us whether we like it or not. Technology, of its own accord, goes in a certain direction. [...] To change this structure or redirect this movement we have to make a tremendous effort to take over what was believed to be mobile and steerable, we have to become aware of this independence of the technological system, as opposed to the reassuring conviction of technological neutrality. —Jacques Ellul

“Recent months have seen AI labs locked in an out-of-control race to develop and deploy ever more powerful digital minds that no one — not even their creators — can understand, predict, or reliably control.” This statement preceded the recommendation, signed on March 22, 2023, of a six month moratorium on AI research, following the advent of ChatGPT and generative AI programs.1 Signatories included noted scientists, bigwigs of Silicon Valley, and AI researchers from Yoshua Bengio [Turing Prize] to Steve Wozniak [Apple], by way of Stuart Russell and Elon Musk, alongside various other experts, professors, and engineers. This moratorium, widely trumpeted in the media, gave an ambiguous expression to anxieties concerning artificial intelligence, by invoking a kind of escalatory millenarian fantasy: “Should we develop nonhuman minds that might eventually outnumber, outsmart, obsolete, and replace us?” The petition echoed the concept of a “technological singularity,” i.e., the moment, theorized at the end of the last century, when AI would attain a form of “consciousness” and autonomy, paving the way to a technological acceleration that man would no longer be able to control.2 A relatively new question also emerges here: once we jettison the usual way of speaking of an “AI with utilitarian purposes,” how are we to position ourselves in relation to such an unreliable technology, one that presents not merely a risk but perhaps even a threat to humanity? Has it become incomprehensible even to its creators?

Yet another petition was sent out at the end of May, whose form itself was puzzling. Entitled the “SAFE AI Statement,” and initiated by researchers and engineers in AI, it made a simple appeal: “Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”3 While the hypocrisy of this statement was pointed out by many, few seem to have noticed the novelty of a discourse that effectively shatters a conventional assumption about technics: not only is technology not neutral, in this case, it’s not even “good.”4 Let us also note, in passing, that although this technology seems to already dangerously escape the control of its creators (a risk exists, but it can only be mitigated), the element of hostility inherent to it is not seen as an a priori problem but merely as an a posteriori risk (of extinction).

This tale of an intelligent machine turning back against man serves to discourage a more rational approach which, by keeping to a critique of technology, would also see in AI a risk of enslavement or of man’s disqualification. A myth sweeps everything aside.

The feeling instilled is thus a strange one, as if we were living in a science fiction world instrumentalizing its own codes within itself. A kind of metanarrative, a sci-fi simulacrum masking a dystopian horizon, itself fully tangible and real… In order to grasp the matter more clearly, we need to distinguish between science fiction and dystopia, genre and subgenre, to recall how these two fictional genres feed off each other, how they operate through a bracketing of the real.

The “singularity” is the Frankenstein myth gone askew: the Promethean allegory is vacated in favor, first of all, of a belief in the omnipotence of technics, which runs completely contrary to the original story. This millenarianism reading of the singularity must be rejected. Instead, we should interpret it not as a fantasized projection of a possible future but as an allegory of our own present. This will, in turn, allow us to reappropriate the older narrative and restore its metaphorical significance.

As it happens, the “myth” of artificial intelligence echoes to a large extent Jacques Ellul’s interrogation, in the mid-twentieth century, of the place of technology in our societies. The myth of AI translates something that has remained unthought. It portends a possibility that would take us beyond the “technological system” (1977) so precisely described by Ellul, realizing fears he had anticipated already in the book’s introduction. The myth of AI materializes, in a negative form, the danger of a utopian society, a system closed-in by technology: a “Megamachine” wherein individuals and social relations would be governed in fact by technical principles (which is to say, reduced ultimately to simulacra). The aim of the present essay is to draw out the contours and consequences of this claim.

I. Technics and Myth

The most “enlightened” point of view on AI — critical or otherwise — generally tends to overlook the myth that surrounds it, simply shrugging off the question. If AI is meant to be the realization of what science fiction had announced or “prophesied,” it would in actuality have little to do with this millenarian vision. The trouble here is that an excess of rationalism can lead us to consider the technical phenomenon in an isolated manner, as a thing unto itself. The temptation is always great to relegate its myth to mere fantasy. However, by doing so, we end up concealing the mythical construct that holds together what would otherwise, with AI, be no more than an assortment of techniques and applications without any connection or foundation. In other words, it is precisely through its ambivalent relationship with the myth that we can understand what artificial intelligence is. For this reason, before turning to the ideas of Jacques Ellul (who always took care to address the beliefs and myths of our time5), we must first consider this relationship between AI and myth on its own terms.

Even among some of AI’s most fervent advocates, one finds the conviction that myth and technics should be held apart. After all, the technical performance of artificial intelligence ought to provide the very proof of its rationality, irrespective of any belief system. From this vantage point, irrational predictions and fears surrounding AI only wind up nurturing a kind of techno folklore (with AI, we are never very far, in fact, from the freak show, the magic act); or worse, they advance private interests that are themselves parasitic.

However, while a purely technicist vision (I prefer this term to “utilitarian” in its somewhat dated sense6) might wish to distinguish the true progress of AI technology from the singularity (as the product of cranks), nothing allows us to separate them so neatly. The myth is one and the same (we shall see later the precise role that this nightmarish sci-fi fantasy plays).

There’s no point, moreover, in discrediting the allusion to the singularity contained in the petitions mentioned above, or reducing it to a mere marketing ploy, even if it is that also (the insinuation of a technology so powerful…all-powerful). If the ambiguity of the myth is so striking, this is because what is at issue is not merely the secondary question of the power we lend to the machine, and which we simply need to regulate, but the more complex and convoluted question of the sacralization of technics on which the power that we invest in AI or not depends. Unlike the myth of the singularity (which is extrapolated from it), the myth of artificial intelligence nurtured by the sci-fi imaginary goes no further than the hypothesis of the possible emergence in the “machine” of a form of consciousness. It’s this myth that we must address first.

Just as the singularity myth works to discourage in advance any critique of technics, to limit ourselves to a deconstruction of this myth would be no less problematic: on the one hand, all the arguments against it play in its favor, since the myth enjoys the appeal of a fantasy or false pretense (mythifying and demythifying discourse thus tends to merge). On the other hand, the rationalism of technics, understood through its active principle as performance [efficience], seems to take on the task of demythologizing itself, even if AI itself tends toward the personification of technics. Although this apparent contradiction might have allowed myth to evade analysis, the fact remains that myth and technical “rationalism” are products of one another, they interpenetrate and amalgamate in their shared belief in the omnipotence of technics. In short, rather than isolating myth from technics, it is precisely through their mutual relationship (and apparent contradiction) that artificial intelligence is constructed and allows itself to be grasped.

“Technology is no longer subordinate; rather, it legitimizes scientific research” (TS, 266), observes Jacques Ellul. Heidegger, another thinker of technics that Ellul didn’t especially like, arrives at a similar conclusion: “Technology…doesn’t derive from science; on the contrary it is science that derives from technology and is, in a sense, its armed wing.” With this evolution, science and technics seem in reality to have become one. While the preponderant character of technics is important, we shall see that it is from the very ambivalence of this coupling that AI draws its substance and dynamism.

Considered as a science or field of research, artificial intelligence is Promethean; considered as technics, it has no such predetermined meaning. Indeed, what do GPS and ChatGTP, melanoma detection techniques and lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS) have to do with each other, except that they all use AI? What does this have to do with myth?

At first sight, the profusion of AI technologies makes its very concept hard to define. AI is generally understood in terms of three predefined stages: weak, general, and strong AI. Weak AI refers to forms of automation and technological complexity that we’re all readily familiar with: decision support, neuroscience, detection systems, complex statistical models, etc. General AI [AGI] is associated with the simulation of human intelligence, including emotional computation, cognitive simulation, thought, language, etc. Strong AI, finally, refers to the creation of a truly autonomous artificial intelligence, i.e., one equal or superior to human intelligence, and is therefore situated in a purely hypothetical future that is the stuff of myth. Although sometimes confused with AGI, strong AI is distinguished by the introduction of the notion of consciousness.

Of course, this typology is only interesting insofar as the world of AI engineers and designers invokes it when framing their technical and theoretical challenges (work on language models all revolves, for example, around AGI). Could one not object at this point that technics, which “determines research” — the latter being only a means to an end — never in fact assigns itself such general goals? Indeed, on closer examination, artificial intelligence is no more than the sum of its various byways. Here we see precisely the technical ambiguity upon which AI thrives. AI is nothing but the product of a misunderstood denaturing of technics by myth, which cannot therefore be isolated from it. In contrast with the purely technical “ideal,” AI technologies have their own peculiar structure or logic.

(i) We may distinguish a first class of AIs that are inserted into other, already complex technical systems. For example, into computer programming, the logistics industry (flow and stock management, transport), in the design of artificial intelligences themselves, etc. In these applications — which remain the most invisible and least controversial — artificial intelligence, as a pure technics, appears to distance itself from myth, while at the same time exposing a fundamental feature of it: autonomization.

By integrating into technical systems that are already autonomous (logistics, complex environments) and that humans can only modify or bend in one direction or another with great difficulty, this use of AI seems to validate a general trend. When it comes to creating computer tools, or the creation of AIs by AIs, autonomization calls the “creative” gesture of computer engineers into question in a new way. Of course, the very notion of computer engineering bespeaks a form of autonomy (of programs, of systems); but does the computer engineer, in this case, somehow hand over the controls to the machine? Does such a digital system push towards even more autonomy for itself? As for the case of the creation of AI by AI: does the engineer push this technology towards a form of autonomy, or is there not already a “natural” tendency for computer technology to become autonomous? The answer seems to be “a bit of both.” The computer engineer compensates for what technics has stripped from him (since technics very quickly eludes the technician) by investing this technology with a virtual power still to come: a vocabulary is mobilized, the AI thus conceived is named “child” (the Nasnet system generated by Google’s AutoML) and is imagined to have the potency or potential to inspire other models of AI in the future (a call is put out for other developers to take up this technology and perfect it).7 AI technology is a way of steering a given technology (computation), whose characteristic feature is already to autonomize itself, toward further autonomization. Meanwhile, the projection of human categories onto the technical object invests it with a particular meaning. “AI research” systematizes this autonomization in an ambiguous way, raising it to the status of subject. It promises a constant power relation of man to technology and technology to man. Technics is no longer understood as a means to power but as power straight out, power as such (like fire or electricity).

The concept of artificial intelligence dates back to the invention of the computer. Since the 1950s, when the concept was first elaborated, and well before the technology itself encouraged the hypothesis, the ambition was clearly demiurgic and Promethean. Although the research remained in the theoretical domain, the optimism of its pioneers — from Alan Turing to Marvin Minsky, by way of Allen Newell and Herbert Simon — declared that an AI with similar or superior capacities to human intelligence was foreseeable within the horizon of less than a generation.8 This demiurgic hypothesis of an AI research with no practical aims or applications has become all but self-evident today. The metaphysical Promethean project, the questioning of consciousness and the achieving of a form of computer consciousness (the “Turing test”), underlies all research in AI.

The advent of cybernetics in the same period as the formulation of the concept of AI popularized the idea of an integrally technicized science, no longer having recourse to anything other than technical reasoning for formulating, testing, and validating its theories. In this vein, the theorization of artificial intelligence — intelligence that can be likened to a calculation or computer program — would seem from the outset to be nothing more than a technical challenge: its theoretical aspect gives way to the technical, then the practical, which nevertheless always retain this scientific, experimental coloration.

In this coupling of science and technics, it is science that provides the dynamic impetus, making artificial intelligence an area of research, unifying and orienting its various technical forms, just as it unifies the different scientific corpuses linked to this area of research. Beyond the hybridization of technical processes, the aim is to strive towards a technical, functionalist synthesis. The Promethean myth of AI is the product of this technoscience, this science monopolized by technics, as the fire it has stolen. Intelligence as a computer program. In fact, technics and research sets itself no boundaries, and it is precisely in this regard that technics comes to be traversed by a myth: in its dual, changeable character, artificial intelligence is at once technics and technics-in-the-making.9

AI is a projection of man onto the technical object (the anthropomorphic myth) and a projection of technics onto man (the brain-machine as postulate). These two conceptions, inseparable though apparently opposite, mirror one another. Nevertheless, it can be hard to follow the logical thread from the theoretical, metaphysical object to the technical, practical application. If, theoretically, artificial intelligence and human intelligence function in a similar way, what makes artificial intelligence a technique for man? What use could he make of it? This is the question posed by the thinker John Searle, less as a philosophical question than as a practical, commonsense one: “If we are to suppose that the brain is a digital computer, we are still faced with the question, ‘And who is the user?’”

To conceive of intelligence as a mathematical operation, as something that can be quantified and manipulated through a computer language, is already to inscribe our relationship with the tool within a process of reification. It is one thing to make a tool that we use, it is something else to make tools that are supposed to reflect our intelligence. In the latter case, the relationship with the tool is no longer at all the same, but has become reflexive: man observes and projects himself through the technical prism.

The whole question of AI and AI research boils down to a refusal from the outset to think our relationship with this technology. At an ideal level, it becomes a pure technics without any specified use, a mental construct, a demiurgic delirium. In concrete terms, through the applications found for it, it draws the human being into a reifying process, like a hall of mirrors. The so-called question of replacement — a false question — is a direct result of this absence of any perspective concerning the use of AI technology, the way it is apprehended from the start as a metaphysical object, as potential technique or as pure potency.

An empty, illusory (illusion-creating) structure is at work here. There is, actually, an identity between the model (human intelligence) and its translation into digital language. Once intelligence, grasped simply as calculation, is carried over into the technical domain, its process formalized, artificial intelligence then becomes a model. It is modeled, as much as it models. The principle of “augmented” intelligence via artificial intelligence already presupposes the reduction of human intelligence to the level of technics or calculation.

The second category that must be set out here therefore includes all those AI technologies that tend to shape or model human intelligence. For they constitute the flip side of the myth.

Indeed, we can think of these different technologies, the different types of AI, as so many models. “AI is what hasn’t been made yet,” according to researcher Douglas Hofstadter. An evolving technology, AI is also a tendency grouped around the notion that human intelligence can be transposed, i.e., falsified, into a computer language. AI aims to achieve a synthesis (AGI or strong AI); it must first be understood first of all as something underway, in constant evolution (consonant with “Moore’s Law”10). What is it striving to be, both potentially (in the elaboration of its myth) and in its reality?

Empirically speaking, research in AI (in keeping with this idea of intelligence understood as technics) attempts to break down and then recompose our ways of thinking, our faculties of perception, reasoning, speech, communication, decision, etc., translating them into the computer language of tasks.11 Many applications, albeit still in their infancy, are essentially derived from this idea, with the various AI technologies constituting the threads and strings of this puppeteer’s “science.”

This idea, which is foundational to AI, and which implies that man could be replaced by the machine for certain tasks a computer may eventually perform better or more efficiently, utterly disconnects these techniques from our relationship with them. However, although they might replace the human, it is still the human that interacts with them, which shifts the matter back to a more essential conception of man as machine: military uses (lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS)), police uses (prevention, automated identity checks, management of gatherings, surveillance, etc.), but also the use of AI in healthcare (diagnostics, medicine as “expert system”), its possible use in the political sphere (administration) and in law (acceleration and simplification of court decisions), in education (models, techniques of cognitive science), AI in the tertiary sectors, services (automated online assistance), recruitment, chatbots, etc.

In reality, this conception of intelligence as the completion of a series of tasks or calculations extends with AI to a potentially infinite number of techniques, the myth slipping itself into a purely technicist discourse without appearing to establish a direct relation with it. Thus Kaplan and Haenlein, for example, define artificial intelligence as “the capacity of a system to correctly interpret external data, learn these data, and use this learning to accomplish certain specific objectives and tasks while adapting in a flexible way.”12 This minimal definition tries to reduce AI to a tool for a given application. Yet we clearly will understand nothing about this technology if we don't take into account the entire range of applications it generates, as well as its tendency to be grasped as a potency in its own right. What’s in question is not just “specific objectives and tasks,” but a vast field of applications in constant development, achieved through processes that are similar in every respect (the algorithmic “system” of AI).

In this definition, the anthropomorphization or personification of technics has no a priori part to play either. It will enter into play further upstream, through a way of speaking about or conceiving technical tools, through the development of anthropomorphic technologies (e.g. through the use of language), and more generally through the orientation of AI research towards autonomization.13 This last point is certainly the most important, and assumes the deceptive appearance of a pure technicity. Generally speaking, AI is the projection of a power or potential in technology (with the corollary of renouncing mastery over it, once again raising the question of use). It is a belief in the omnipotence of technology, embodied in the paradoxical quest for autonomous empowerment — which, in the final analysis, is nothing other than a sacralization of technology.14

AI proceeds through a constant back and forth between myth and technical application. “Rationalist” technical discourse and myth-making are deployed interchangeably, reinforcing each other in a dynamic way, in the idea of an evolving technology, unfinished and incomplete by nature.

The two categories of AI mentioned above are not sealed off from each other, but themselves form a system. More generally, artificial intelligence is a way of ordering the real, according to a norm (technically assimilable by the machine) or computer (re)programming. It furnishes a unified, autonomous model whose particularity is to spread here, in the digital domain, without any brake: AI in finance (algorithmic trading, market forecasting systems, which in turn condition the market, the economy), media algorithmization (content production and suggestion), automated translation (according to the idea of a single language, reduced to calculation), data management (extraction, exploitation), digital technologies (personalized management, moderation, content suggestion), etc. Highly specified in its original principle (the demiurgic horizon of “research in AI”), artificial intelligence thus tends in practice to be diluted to the point of coinciding with the whole digital system, forming a generalized cyberneticism. A cybernetic model of society that preserves from myth only a mirror image which man struggles against, fixates upon.

These technologies thus remain mostly invisible, in the background. Despite their appearance as a strictly technical issue, they are part of an environment that is already highly technicized, and contribute more broadly to the virtualization already underway in our societies, whereby man and his social interactions are also no longer seen as anything other than technical matters.

The aim of AI is not so much to replace man with the machine but to make it so that man behaves, acts like a machine, that society as a whole technicizes through a subtle play, by turns, of normalization and imitation. AI intensifies the underlying process of technical representation of our society, where man tends to enter himself as a digital quantity (and where, consequently, he no longer has any importance).

Effectiveness and representation are thus intrinsically linked through AI: the algorithm — or “intelligent agent” [agent-based model] in the anthropomorphic jargon of AI research — effects a constant readjustment in real time, via deep learning, of the tasks it is supposed to do, but also of the representation of the environment [model-based agent] with which it interacts. The world thus becomes measurement, statistics in real time. Through the accumulation of data, AI optimizes this representation (of social systems or phenomena, behavioral phenomena, etc.) in a technicist sense. It belongs to the nature of this system to then bring this “representation” into closer alignment with its calculations through the technical operations it performs: the technical system isn’t that of artificial intelligence, but the broader one of artificial intelligence in a given social environment, which it tends imperceptibly to modify and technicize.

Antoinette Rouvroy, who sees in this statistical organization of society a form of “algorithmic governmentality,” does a good job of analyzing the new order we’re dealing with, which strives for the perpetuation of a social model of technical power (capital, in this digitalized world, has become an accumulation of data).15 This management by algorithms aims at a “neutralization of uncertainty” or emergent phenomena, a cybernetic mode of regulation that anticipates and excludes every form of accident through the granular analysis of behaviors and preemption.

We are dealing with a technology of reflex, of doubling: a mirror apparatus.16 Time itself becomes that of the computer, while the immediate, discombobulated future is as if doubled by the algorithms. With algorithmic trading, managed by artificial intelligence, the algorithms don’t predict the future so much as they produce it. Law is potentially no longer anything but a correlation between facts, a statistical administration (not unlike medical science, etc.).17

Let’s note here, finally, that while this cybernetic empiricism takes error into account and continually registers it in its system, the statistical principle of “deep learning” remains, in the end, less than reliable (the limit of calculation applied to the living). The important thing, what remains in the final analysis, is basically just the model itself — mirror, specter, or technical prism: this regime of appearance systematized through technics.

The more invisible they make themselves, the more the myth seems to fade away, the more effective the AI techniques become (but in the sense of a system’s normalization: itself generating a slew of aberrations in turn). What technics achieves is a form of cybernetic utopia, which is something quite different from the figure of the android, which here only has an accessory role. But myth is always there: this apparent disappearance of the myth, its invisibilization in the digital system, is matched by an inflation of the myth in the collective imaginary. A certain ambient discourse, steeped in sci-fi clichés, together with the most spectacular advances in AI research, ensures the reproduction of an AI narrative or horizon in the social imaginary.

In a dual movement, the inflation of the myth conceals the general alienation brought about by technics, with AI tending in a subjacent way to coincide with the digital system as a whole (AI never being anything more than a personification, or algorithmic conceptualization, of the computer — see the work of Turing). This reversal runs contrary to the Promethean dream of AI: the omnipotence of artificial intelligence only resides finally in its effectiveness as a system, as an apparatus assimilating the human being to a statistics, integrated into this technical system — a far cry from the realization of an all-powerful demiurgic creature.

Every advance in AI technology presents itself as a demythification, and yet contributes in reality to the fabrication of the myth. While AI seems to be divided into an indefinite number of techniques, research, on the other hand, operates in a synthetic manner (with the myth as its horizon). These successive syntheses place the Promethean idea of the intelligent machine in perspective. They correspond to an advance of a technical kind, presenting itself first as such, but always with this anthropomorphic identification (most often in an ambiguously playful way).18

The last category that we must distinguish is that of the recently appearing language models such as ChatGPT, which appears as this synthesis today. The strictly technical function of the language models isn’t very clear. They seem at first glance to be gadgets, and have been received as such. The speculation around these models is symptomatic. They are said to have a multitude of practical applications (being able to serve, for example, in work tasks or in training). These models approach the myth (the AGI)19, and are more than techniques in the strict sense, but are techniques in the making.

The problem posed by the myth of artificial intelligence, which remains a figment of the imagination, can be clearly seen: if it ever became real, it would thereby cease to be a technics. A truly autonomous AI presupposes by definition that it no longer be reducible to technics. It becomes pure artifice, an automaton for which one had lost the user instructions, as it were. A technique is essentially an operation or calculation, a function for the purpose of obtaining a result. AI, through its process of autonomization, thus flirts with the idea that this result could at some point enter into question, with no further purpose.

Artificial intelligence is a virtualization of technics. It is technics at the limit, drawing its substance from this limit. If its myth became incarnate there would simply no longer be any artificial intelligence (as an object of research), no possible technique or use.

What then is the role of the myth of AI, of this technological millenarianism? What, ultimately, does this identification of myth and technics amount to? AI goes well beyond the ancient myth of progress, of the ceaseless perfecting of techniques, of science. The fantasy of an end of technics, through technics, exposes a kink. This aporia of the algorithmic tool, of the machine, which accedes to consciousness and breaks free of man, seems only to mask this more down to earth, mirror-like idea of man himself becoming technical.

Until the machines rise up, artificial intelligence is, in sum, nothing more than a mirror operation upon man (who believes it’s the other way around). The idea of the brain as a machine is after all the primary, absurd idea of artificial intelligence. A pure fantasy, the dystopian horizon of technics that it seems hell bent on actualizing.

II. Ellul and AI

As early as 1954, at the same moment that the first “thinking machines” were being developed, Jacques Ellul published his seminal work, The Technological Society. At the time, his argument found little resonance in the context of the Cold War. In his view, capitalist or post-Marxist ideologies no longer held any importance: productivity, the gains of productivity (profits), the economy, were determined by the development of la Technique, a “technological system.” According to Ellul, technics [la Technique], or the technical phenomenon20 has become the determining factor, the one that, more than all the others, shapes and structures modern societies.21 This spontaneous phenomenon of the autonomization of technics dates back to the first half of the 20th century, to the prolongation of the industrial revolution and its “machinism,” eventually morphing into a “technological system” in the 1950s with the appearance of the first computers (TTS 20-23).22

Today technics establishes itself in our societies as its own cause, forming its own “environment” in which the means has become an end. There is no longer any idea of progress, only endless complexification or “autogrowth.” In this self-managing system, everything eventually turns into technics, understood as the resolution of the problems it itself causes. Having autonomized itself, this “technological system” is marked by an interdependence between various techniques or sub-systems. As a vector of standardization, of that “rationalization” that underlies the belief in the neutrality of technics23, this system devastates and flattens everything, and is now universal. The single-minded quest for efficiency, the predominance of technical criteria at all points, at every level and in every domain invisibilizes, denatures, or destroys little by little everything that resists being subsumed under it.

Participating in this way in a process of general artificialization, this technological system has become the regime of supreme rationality, by which and to which everything conforms, aggregates, and which for human beings constitutes the primary experience, at once a new “nature” and a source of alienation.

Ellul describes quite precisely what technics is, but doesn’t tell us what it fundamentally represents, of what it would be the sign. There is no anthropomorphism here; Ellul doesn’t humanize technics any more than he divinizes it.24 It has the appearance of “a strange barrenness” (TS, 231). In an ironic twist, it is man’s desire for power that eventually reduces him to powerlessness. Technics was that by means of which man sought to become master; however, once it becomes autonomous, it winds up enslaving him.

Technics is an abstraction that governs us. The field of politics, now subjected to the reign of technics, loses its autonomy and continues to shrink. At the same time, and proportionally, the domain of the State, as a coordinative structure, perpetually expands, likewise in the service of technics. Man must first take cognizance of this phenomenon. Because this technological system is hidden from us in a way, we are left with “vivid and colored apprehension of a nonreality, which has no other function than to camouflage the mechanism and satisfy us with the ‘miracle mirage’” (TS 16).

In spite of having suffered and undergone this autonomization of the technological system, it still remained poorly understood, indeed even totally denied. With the advent of advances in AI, it now assumes an anthropomorphic appearance and even seems as though it were willed, desired (in the cybernetic sense). As AI and “algorithmic governmentality” replace human decision, the technical fact replaces any de jure right or law. For Ellul, awareness of the technological system’s autonomy formed a prerequisite for any action. Through its millenarianism, artificial intelligence postpones and reduces this reality of the independence of the technological system to some moment in the future, converting it into a science-fiction fantasy whose supernatural dimensions ensure that the human has no purchase over it. In other words, this unthought of the technical phenomenon in our societies takes a more refined turn with artificial intelligence: its repression becomes all the more sophisticated once it becomes dependent upon a fiction, a mythic imaginary construct.

Artificial intelligence tends to coincide with this technological system unified by digital networks, itself already in complete rupture with “the old world”:

The sole function of the data-processing ensemble is to allow a junction, a flexible, informal, purely technological, immediate, and universal junction of the technological subsystems. Hence, we have a new ensemble of new functions, from which man is excluded — not by competition, but because no one has so far performed those functions. This does not, of course, imply that the computer eludes man; rather, a strictly nonhuman ensemble is establishing itself (TS, 102-103).

AI is the replacement of this “new spontaneity” by a mythical horizon (TTS, 26).25 As the personification of technics, it constitutes a doubly non-human horizon: to fetishize this “new digital ensemble” through the illusion of accessing a new form of intelligence, of consciousness, is in effect to grant it “rights,” a supplementary autonomy which the computer did not previously possess.

What AI adds to the technological system described by Ellul is an image of technicized man — that is, a technical model of man as no longer anything but a function, a technical vector: an image that could perhaps be characterized as subliminally manipulative, if this simulacrum produced by AI were not also an ironic turning back [retournement] of technics upon man.

In a system where technics has become autonomous to the extent of replacing the real world with the digital one, AI seems to constitute for man both his most probable and most unreal horizon, a horizon that one tends to call dystopian (yet without considering what this term covers here, what it really signifies).26

This dystopian phenomenon is a basic tendency in our societies, of which the gradual installation of AI forms only one aspect.27 It operates via a meta-theater that recycles themes, clichés, and myths of science fiction (of which dystopia is precisely one of the founding genres). This stock-in-trade of a science fiction-become-reality (and not the reverse) tends to obscure the ways that the genre is exploited in order to establish a model of society. What appears as the most accomplished fact (“prophesied” by sci-fi) is most often just a mythical, ideological sort of construction (AI, dystopia, the worst post-apocalyptic scenarios, predictive Dickian models… everything is fit for recycling). The posture is that of a society nourished by the sci-fi imaginary, falsely conscious of itself, of its technical prowess, while the underlying reality is precisely a destruction of the imaginary and an alienation, finally, through technics.

In this dystopian process, AI nevertheless seems to play a quite particular role. The idea of technics or the machine dominating man is partly accepted, or at least envisaged (this is evident, for example, in the dogma of the singularity). The technological system tends to close itself off by this sacralization of technique — precisely what Jacques Ellul seemed to fear. The “entertaining” myth of AI tends to mask this self-alienation of man (not so much through technics as through this sacralization).

The mythical horizon is here exactly the same as the dystopian horizon, but it conceals its logic, its mechanism. Before looking at how this game of occultation operates, let’s first consider the means by which the myth is propagated: technological achievement (the successive syntheses of research in AI) and the very profusion of AI technologies themselves, discourse (whether technical or more theoretical — obviously “transhumanism”), media coverage, numerous debates, fictions, etc. It’s also, of course, a general economy (with the idea of a productivity gain through a replacement of man by the computer): GAFAM, the “giants of tech,” the digital industry, profit massively today from the advent of generative AI’s (a market capitalization of tens of billions of dollars!), with crazy sums of money now being invested in AI.28 Completely central here, to be sure, is the power of this industry, its immense influence in this domain, the technoscientific discourse they proffer relative to the myth, which corresponds to the fabrication of a narrative, which is to say, the manipulation of narrative tools, of concepts issuing from science fiction. But beyond this manipulation, there is something unconscious going on here: the perfectly ambiguous myth of AI seems to reveal an alienation right within the professed discourse. Strictly speaking, it’s not a political discourse but a technical one, which only focuses on means, and on a short-term wager (on the future and uncertain development of these technologies).

Parenthetically, there is not necessarily a cynicism in this discourse, and the belief in this myth is not just a posture (the currently most influential figures of AI research, the Turing Prize winners Bengio, Le Cun, and Hinton, all earnestly raise the question of the myth, of general or strong AI, and of the singularity — Hinton to the point of eventually resigning from Google). Moreover, while from a certain viewpoint the question of the myth may seem abstract and of interest only to a technical elite, it troubles the whole society, and acts like an unconscious. The completely ambiguous term, research in AI, is itself to be considered from the point of view of a (Promethean) quest and seems to refer to a collective unconscious. The question of the dilution of responsibility in the technological system, and of the autonomy of technique, is central here, yet is occulted by the power of the myth.

At the famous Dartmouth conference of 1956, where AI was conceptualized, John McCarthy proposed the term artificial intelligence as distinguished from the term cybernetics, which he considered to be too connected with its founding father, the celebrated mathematician Norbert Wiener.29 “Cybernetics” refers to the idea of society as a machine, a system of communication. The two men thus shared the same belief in the advent of an intelligent machine: while McCarthy worked toward that advent, Wiener, more distant, expressed fears that an intelligent machine would transform our world into a science fiction nightmare if one did not control it. With AI, these two visions now combine. The evil robot and the dystopian horizon share a single reality, each the negatively mirrored reflection and the metaphor of the other: the machine replaces man, while man becomes machine.

As AI technologies are put in place, must we still speak only of a dystopian horizon (or tendency) rather than a quite real dystopia? Here dystopia is closer to a process than a fixed form. It is a form of dystopia utilizing the narrative of science fiction, fiction as a tool of development, of configuration, towards an idea of a purely technicist society.

The (French) Wikipedia site states that “in a dystopia, technological development is not a determining factor,” and that “the supernatural scientific or metaphysical postulates simply do not have their place there”: they can constitute a horizon, but not a condition.30 For all that, the dystopian ideology can make use of narrative techniques (and even of myth — here, artificial intelligence) to arrive at the establishment, the shaping of a dystopian system (and this even in a rather unconscious way — I mean not formulated in those terms).

To understand how this works, we need to decorrelate science fiction and dystopia. More deeply, dystopia would not just be a (narrative) genre, and hence not necessarily science fiction. It is a political and social system of a utopian type that has gone bad.

One would be mistaken, moreover, to think — according to a certain cliché trafficked by science fiction — that with AI the dystopian sentiment would pertain only to machines and robotized interfaces, in place of man. Here, this sentiment appears rather in a society that has adopted the principle of being governed only by technics (we know, since La Boétie, that servitude to the social body consists only in a certain degree of integration, or acceptance).

Modernity is strewn with fables in connection with the technical advances, fables which man has invented to sell or extract profit from the machines, fables that could be called positive. A fact with no precedent: with AI, we have the creation of a myth, by the very people who are developing that technology, where artificial intelligence would threaten humanity with “extinction.” It’s also a reversal of the way in which we are generally presented with the new technologies, which would basically depend simply on the good use that one makes of them: although instilled in a rather diffuse way, with the technological singularity, technics’ bad dream, there is born a form of nightmarish science fiction fantasy, of perverted myth. Whether this fantasy might be a sincere fear (phobia), a self-interested posture, or even a real expectation (by the transhumanist movement in particular) doesn’t have much importance, really. The fantasy rests essentially on a sacralization of technique.

When it comes to the effect on modern societies of works of science fiction presenting a scary technological invention, Ellul raises the following problem: “Since technology is nothing like what it has been shown to be, it strikes us as perfectly acceptable and reassuring. We take refuge in the real technological society in order to escape the fiction that was presented as the true technology” (TS, 112). The case of artificial intelligence, with its demiurgic horizon is certainly more ambiguous, but the assessment remains the same: certain individuals can fear the singularity, or hope for it, but the present of artificial intelligence is definitely more down-to-earth. For its part, the technicist, cybernetic utopia/dystopia is well underway.

Artificial intelligence tends to shape, potentially, the totality of our society (down to our way of thinking, our language). Decorrelated from its technical correlations, abstractly understood, the myth remains an object of both derision and curiosity. It penetrates all the more so given that it is, as I’ve tried to show, deeply ambivalent, not entirely assumed as such, allowing it to appear inoffensive. Sacralized at the opposite extreme, AI also operates as a semblance of something.

As Ellul explains, the world is “unified” by technics: the technological system, “instituted” by the computer, has found in digitalization something approaching a universal structure. Consequently, the risk for Ellul was for this globalized and globalizing system to creep towards the technical, cybernetic utopia. “The sole utopia is a technological one […] Utopia lies in the technological society, within the horizon of technology. And nowhere else” (TS, 20). As Ellul also reminds us, “all utopians of the past, without exception, have presented society exactly as a megamachine. Each utopia has been an exact repetition of an ideal organization, a perfect conjunction between the various parts of the social body.” The “perfect” utopian society tends to be technicized in the very social body. In this social system, born of utopia, AI plays a central role: it technicizes human relationships, it tends to make humans into nothing more than technical vectors, shows them and subjects them to this image. The myth that tends to turn back into a cybernetic utopia against man, adjoins to itself the sacred and irrational element inherited from science fiction. It’s no longer an intentional, thought-out utopia, desired as such, but one that is imposed in a manner all the more natural as it seems to emanate from the unconscious of a given society, from the “modern world’s absolute belief” in technics. Nor is it a static utopianism, but always a horizon: more precisely, that dystopian horizon which promises us the millenarianism of AI. One could speak of a potential dystopia, but it’s actually a dystopian horizon, which is not virtual, but is being progressively actualized in proportion to the development of its technologies.

AI in our society translates into an endless preparation for dystopia, for the technological society (no longer governed by anything but technical principles). But artificial intelligence is also just an automaton’s dream. “Technology is inevitably part of a world that is not inert” observes Ellul. “It can develop only in relation to that world. No technology, however autonomous it may be, can develop outside a given economic, political, intellectual context. And if these conditions are not present, then technology will be abortive” (TS, 31). At base, the illusion of AI consists in believing that it develops in a milieu in its own image, one totally artificial and inorganic.

Similarly, Ellul notes several times, in regard to the hegemony of the technological system, that “saying technology is the determining factor of this society does not mean it is the only factor” (TS, 18). The dystopian horizon distilled by the myth of AI — through technoscience’s appropriation of the themes of sci-fi — just perpetuates the reign of technics, of algorithmic governmentality, of the power in place, and it’s nothing more.

The very simple question to be asked, basically, would be: how much longer will we chase after this dystopia, this illusion? If we might potentially never touch bottom with AI, the array of disturbing elements, which will come at one moment or another — without even necessarily thinking of it — to grip the machine is limitless as well.

Ellul seems to have hit upon the origin of the central problem of the autonomization of technics in his 1988 essay The Technological Bluff: “It is in effect a common basic conviction that technique can fulfill all our desire for power and that it is itself omnipotent,” he notes, but it’s also this “absolute belief of the modern world which implies our absolute renunciation of mastery: we delegate power to technics!” (TB, 156) This is where the irrationality of the technological system is lodged, but also that of artificial intelligence, their fundamentally illusory character. To pass from the idea of a (rational) technical mastery to the idea of power through technics yields an “incredible contradiction.”

Regarding this “mysterious” preeminence of technique in our societies, we are aware of Gabor’s famous law: “What can be done technically will be done necessarily” (1971). This echoes a claim Ellul already made in the 1950s: “Because everything that is technical, is necessarily used as soon as it is available, without distinction of good and evil. This is the principal law of our time” (TTS 99). In reality, man’s relationship with technics extends well beyond the framework of rationality. For greyed out man, the object of a “dark transcendence” (Hottois), technics has thus become what appears to him as a “blind and mute engendering of the future.”31

It’s on the basis of the presumption of the neutrality of technique, exempted as it were from every kind of moral questioning, that the technical juggernaut is unleashed: technics is nothing in itself, and “can therefore do what it will. It is truly autonomous” (TS 134). In addition to its autonomy, it has its own reason or logic. It is an appearance of liberty, it “can do what it will”; however, by unchaining itself, it enchains us, proving to be nothing but an operation upon man, a systematic rationalization of his universe.

Artificial intelligence, and particularly the problem of “AI alignment,” synthesizes this ambivalence. The notion of alignment refers to the idea of controlling AI, of an “ethical” regulator (at the end of the day, to make these techniques viable, legal, to “normalize” them). It sums up this contradiction nicely, this utter mismatch between man’s belief in the “omnipotence of technics” and his sovereign ambition to master it: wanting to construct tools so powerful that one ends up no longer understanding how they function and, from another angle, then imagining mistakenly that one can channel this omnipotence. Making AI more and more autonomous, through an array of technical fixes, making sure, in sum, that it can escape us, and at the same time riddling it with rules, with codes, accompanying it with a jumble of laws (which will only be at bottom the reflection of what man imposes, inflicts on himself in exchange). The different moratoriums on AI of last spring, the legislative measures of the European Union and American government, the very notion of alignment, only aim in this way to integrate artificial intelligence, to concretely envisage the cases of use and practice.

A visionary, Ellul anticipated the coming ascendancy of the new technologies, noting that “the numerical universe of the computer is gradually becoming the universe that is regarded as the reality we are integrated in” (TS, 105). The pixelated society has succeeded the society of the spectacle (Debord), spectral man has replaced alienated man. If ChatGPT has provoked so much talk, it’s not so much that there is a risk that artificial intelligence will replace human intelligence, or that it will constitute for us a “narcissistic affliction”(!)32; it’s that the very meaning of language, of what does constitute us, is reduced to nothing therein. It’s that we are coming to realize that this digitalized world, which has become our “real” world, could, as well, no longer be generated except by computers.

In this way, there is the insinuation of a replacement that is much more striking and indicative here than a replacement as such by machines, because, much more than this eventual demotion, the little music whispered in our ears since the advent of ChatGPT presupposes an acceptance, man’s self-persuasion where he sees himself as technique (initially, AI only suggests or “ratifies” an equivalence between man and technique, which turns out, let’s recall, to be merely an inversion of the meaning of the myth).

For civilizational, metaphysical reasons, AI raises more of a question of choice, of man’s responsibility, than what Jacques Ellul led us to think vis-à-vis the technical phenomenon. AI is above all a mirror apparatus, a technical, statistical prism. But in the more metaphysical, Promethean sense, this mirror also seems able to bring man to a reflection, to a questioning about his relation to technics. The reflected image seems only able to come after the fact, and to be just the least flattering one for man, that of a reification through technics. This millenarianism, which moreover would establish an anthropological shift, is also an illusion, however, a mirage that vanishes as one advances towards it. AI does not really “reflect,” and it’s only a fantasy of our technological system, an image that evaporates in the end. A dying technics, of no further use.

If everyone’s responsibility (especially in the political and market spheres) thins out more every day in the globalized technological system, it’s always, when faced with this technicized state of affairs, the notion of liberty that is at stake (for Ellul, this notion is central: if he demonstrates, so implacably, both the hegemony and the impasse of this system, it’s the better paradoxically to come back to this liberty, which undergirds his thought).33

The debate over the benefit, the utility, of such a technology is deceptive; there is in reality only one choice to make with artificial intelligence, which is whether we wish to sacralize technics, or not. Ellul for his part never posed as a technophile, nor as a technophobe; however, he rejected the sacralization of technics entirely. For our part, it remains to be determined what it would mean to desacralize.

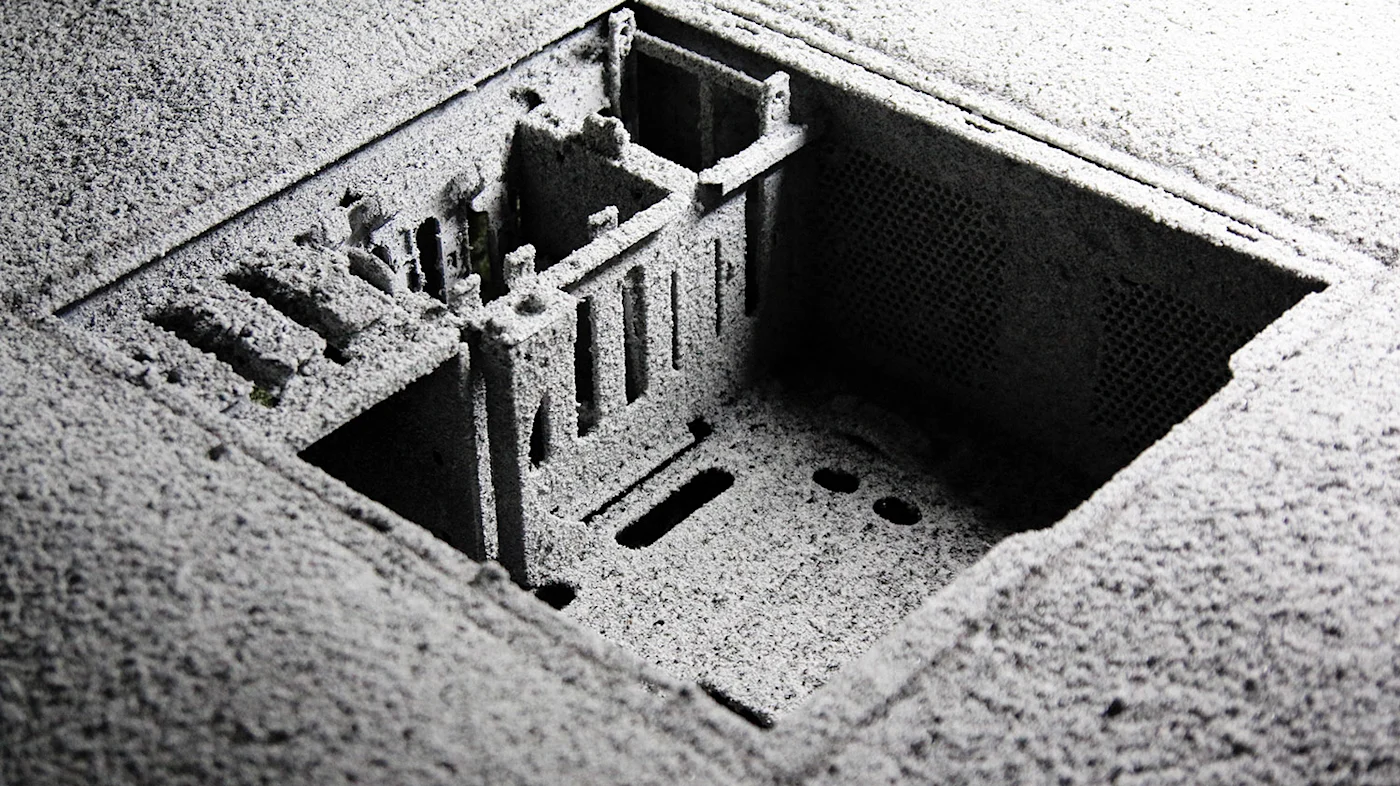

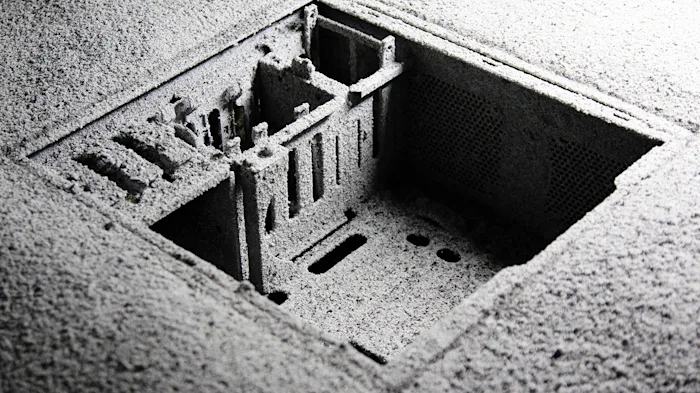

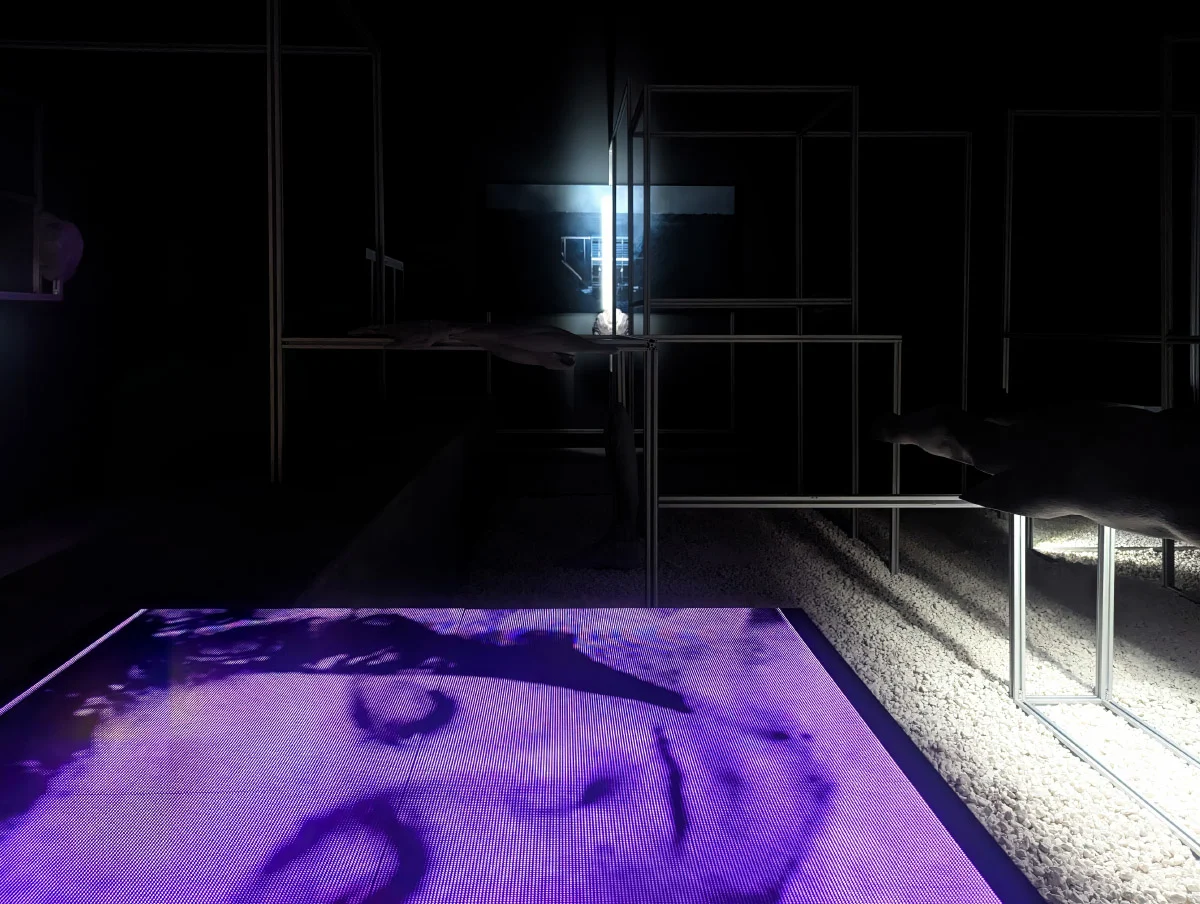

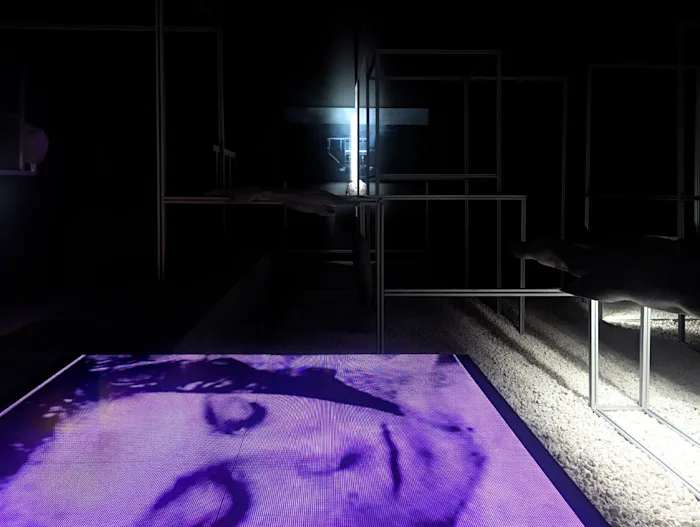

Translated by Robert Hurley. An earlier draft was first published in French on Lundi matin. Images: Gregory Chatonsky

Notes

1. Various, “Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter.” Online here.↰

2. See Vernon Vinge, “Technological Singularity,” 1993. Online here.↰

3. See the “Statement on AI risk of extinction” Wiki for more information. ↰

4. This is what Jacques Ellul calls the “ambivalence” intrinsic to technical progress. See La revue administrative (1965), but also Technological Bluff (1988): “The development of technique is neither good, bad, nor neutral, but made up of a complex mélange of positive and negative, ‘good’ and ‘bad’ elements, if one wants to adopt a moral vocabulary.” This theme is also featured in his book Les nouveaux possédés, Fayard, 1973 (online here).↰

5. Our technical world doesn’t really bother itself with theory today. This led Chris Anderson to speak of the “end of theory” (“The End of Theory: The Data Deluge Makes the Scientific Method Obsolete,” 2008; online here). On the surpassing of the utilitarian conception in our technological system, Ellul remarks: “Technology demands a certain number of virtues from man (precision, exactness, seriousness, a realistic attitude, and, over everything else, the virtue of work) and a certain outlook on life (modesty, devotion, cooperation). Technology permits very clear value judgments (what is serious and what is not, what is effective, efficient, useful, etc.). (...) It has the vast superiority over other morals of being truly experienced. (...) And this morality therefore imposes them almost self-evidently before crystallizing as a clear doctrine located far beyond the simplistic utilitarianisms of the nineteenth century.” Jacques Ellul, The Technological System, trans. J. Neugroschel, Continuum, 1977/1980, 149. Henceforth abbreviated as TS. ↰

6. Aatif Sulleyman, “Google AI creates its own ‘child’ AI that’s more advanced than systems built by humans,” The Independent, December 2017. Online here.↰

7. Frederik E. Allen, “The Myth Of Artificial Intelligence,” American Heritage, March 2001. Online here.↰

8. Let’s not forget that if today it has the meaning of technical complexity, or digital computer techniques, the term “technology” is an Anglo-Saxon deformation: technology is only a science of technics. Hence, the term “technology” is preferred to the term “technoscience,” popularized by Hottois in 1977, the former having at present this double meaning (this semantic twist, which says a lot, also taking better account of the current preeminence of technics over science).↰

9. An empiricist law, taken up like a mantra by all the computer engineers, verified since its creation in 1965, according to which the calculating power of computers — namely the number of transistors on the chips of the microprocessors — doubles every two years. ↰

10. Proposition pour un projet de recherche d’été sur l’intelligence artificielle [Proposal for a summer research project on artificial intelligence], as a preamble to the Dartmouth conference (1956), regarded as the “birthplace of artificial intelligence” as an area of independent research: “The study will base itself on the conjecture that every aspect of learning or any other characteristic of intelligence can in principle be described so precisely that a machine can be fabricated to simulate it.”↰

11. Andreas Kaplan, Michael Haenlein, “Siri, Siri, in my Hand: Who's the Fairest in the Land? On the Interpretations, Illustrations, and Implications of Artificial Intelligence,” Business Horizons, January 2019. This definition, the farthest removed from the myth that one can find, derives from the definition by John McCarthy (the inventor of the term “artificial intelligence”): “Intelligence is the computational part of the ability to achieve goals in the world.”↰

12. The symbolic transcriptions of these AI tools leads to a personification or anthropomorphism: the BDI [Beliefs-Desires-Intentions] model, the “networks of artificial neurons,” the reward systems [cumulative reward] in machine learning, the concept of intrinsic motivation, the very term “learning,” etc. ↰

13. See Ellul, quoting Castoriadis : "the unwitting illusion that technics is virtually omnipotent — an illusion which dominates our age — rests on another idea which is not discussed but concealed: the idea of power," The Technological Bluff, 156. (Human power and omnipotence of technique being in contradiction, as we will see further.)↰

14. Antoinette Rouvroy : “The main object of the capitalist accumulation of platforms is no longer money, finance or banks, it is data.” Symposium, “Intelligence Artificielle: fiction ou actions?”, Colloque “Intelligence Artificielle: fiction ou actions?” in La gouvernementalité algorithmique, Variances, July 2018. Online here.↰

15. Giorgio Agamben, What is an Apparatus? (2006): “I will call apparatus everything that has the capacity to capture, orient, determine, intercept, shape, control and ensure the gestures, behaviors, opinions, and discourses of living beings.” https://www.cairn.info/revue-poesie-2006-1-page-25.htm↰

16. See Bernard Stiegler, in an exchange with Antoinette Rouvroy: "For me, the subject of big data in itself, for me, is the subject in fact and in law [le sujet fait et droit]. It’s the famous text of Chris Anderson (2008), frequently commented on, which says that theory is finished, the scientific method is obsolete. What does that mean? It means that the difference between fact and law is outdated. [...] Chris Anderson suggests that we have no more need of theories, that is, law, models: it’s enough to have correlations between facts. For him, factual understanding has become self-sufficient. There is no further need of reason, no need to reason, nor to debate.” Antoinette Rouvroy and Bernard Stiegler, Le régime de vérité numérique, April 2015. Online here.↰

17. These successive syntheses also appear as media events. For example : The Perceptron (1957), Eliza (1966), Deep Blue computer beats Gary Kasparov at chess (1997), Blue Brain (2005), Watson (IBM, 2011), Siri (Apple, 2011), Alexa (Amazon, 2014), AlphaGo beats go champion Lee Seedol (2016), advent of Deepfake technology (2017), Dall-E (2021), ChatGPT (2022), etc.↰

18. See this GPT-4 creators report: “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4.” Online here.↰

19. “It is useless to rail against capitalism. Capitalism did not create our world; the machine did.” This is an admirer of Marx who is speaking! Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society, trans. J. Wilkinson, Vintage, 1964, 5. Cited henceforth as TTS. ↰

20. Ellul prefers the term “Technique” (capitalized in the French edition) to describe how the technical phenomenon establishes itself as a system. ↰

21. Technics [Technique], as understood by Ellul, is “the search for the most effective means, in every domain” (TTS 341). It doesn’t just group together what we understand spontaneously by technique (computer or industrial technique, production technique, machines, etc.), but it is more broadly the search for the most effective method across the board. It is based most often on a calculation, and locates its legitimacy in a science of technics. Digitalization, which unifies the technological system, would be the best example of Technique as a determining factor, but an infinity of techniques govern society, all of them having in common an exclusive search for efficiency, and an interconnection, finally, as elements of the same system.↰

22. If it is “the computer that allows the technological system to definitively establish itself as a system,” this is because it unifies, coordinates the great technical ensembles amongst themselves (TS 98). ↰

23. Ellul takes apart the rationalist illusion of technique as being “neither good nor bad,” a means depending only on ends, seeing this as “one of the gravest and most decisive errors concerning technical progress, and the technical phenomenon itself.”↰

24. It goes without saying, similarly, that for Ellul the autonomy of the technological system is not assimilable to any form of will; it is functional, comparable to a moving train that it would be difficult to stop, to orient… On the transfer of the sacred to Technique: “The technical invasion desacralizes the world in which man is called upon to live. (…) But we’re witnessing a strange reversal: not being able to live without the sacred, he transfers his sense of the sacred onto the very thing that has destroyed its object: onto technique” (The Technological Society).↰

25. “In this decisive evolution — of technology toward its constitution as a system and toward the gradual formation of the trait of self-augmentation — man does not intervene. He does not seek to make a technological system, he does not move toward an autonomy of technology. It is here that a new spontaneity occurs; it is here that we must look for the specific, independent motion of technology, and not in an ‘uprising of the robots’ or a ‘creative autonomy of the machine’” (TS, 227).↰

26. “Hence, we are ready to lend reality to the universe manufactured by the computer, a universe that is both numerical, synthetic, nearly all-inclusive, and indisputable. We are no longer capable of relativizing it; the view that the computer gives us of the world we are in strikes us as more true than the reality we live in. Over there, at least, we hold something indisputable and we refuse to see its purely fictive and figurative character. (...) The numerical universe of the computer is gradually becoming the universe that is regarded as the reality we are integrated in” (TS, 104-105).↰

27. Regarding this chapter of dystopia, consider the biopolitical management of the “Covid crisis,” against a backdrop of “health security.” On this subject, see my article “L'invention d'un moment dystopique,” Lundi matin, March 2022. Online here. ↰

28. Delphine Tillaux, Pourquoi le phénomène est appelé à durer, Investir No. 2595 devoted to AI, September 2023: “Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet (parent company of Google), Tesla, Amazon, Nvidia and Meta. Between the end of December 2022 and the end of July, the market capitalization of the Nasdaq 100 grew by nearly six trillion dollars, of which more than 80% were tied uniquely to these seven entities.” [We were unable to verify this fact —IWE].↰

29. Nils J. Nilsson, The Quest For Artificial Intelligence, 2010, p. 78: “McCarthy has given a couple of reasons for using the term ‘artificial intelligence.’ The first was to distinguish the subject matter proposed for the Dartmouth workshop from that of a prior volume of solicited papers, titled Automata Studies, co-edited by McCarthy and Shannon, which (to McCarthy’s disappointment) largely concerned the esoteric and rather narrow mathematical subject called ‘automata theory.’ The second, according to McCarthy, was to escape association with ‘cybernetics.’ Its concentration on analog feedback seemed misguided, and I wished to avoid having either to accept Norbert Wiener as a guru or having to argue with him.”↰

30. “Dystopie,” Wikipédia, October 24 2023. Online here.↰

31. Hottois, Le Signe et la technique, 1984, 158. ↰

32. “This replacement anxiety would be a narcissistic affliction, basically, a case of man’s calling himself into question, along with his belief in what he has that’s most singular.” Libération, June 19, 2023. Online here.↰

33. Jacques Ellul and Patrick Chastene, À contre-courant. Entretiens, La Table ronde, 2014: “Nothing I have done, experienced, thought, is understandable without the reference to liberty."↰