Escape from New York

Jarrod Shanahan

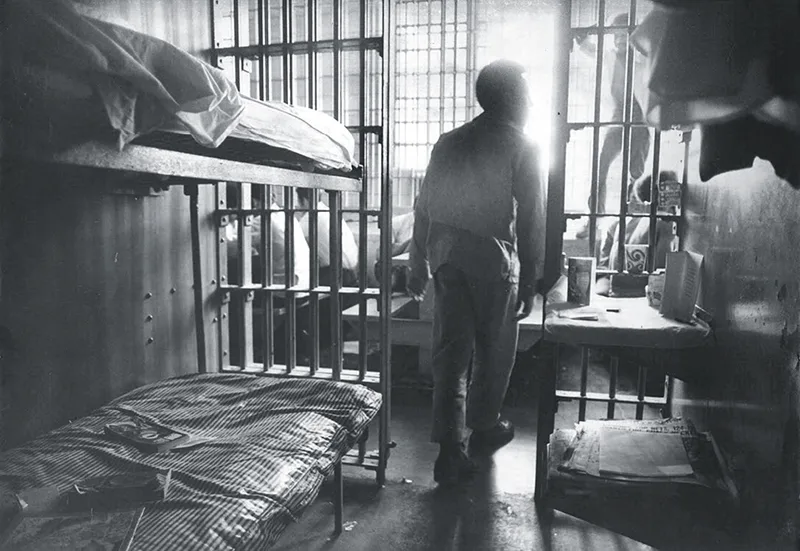

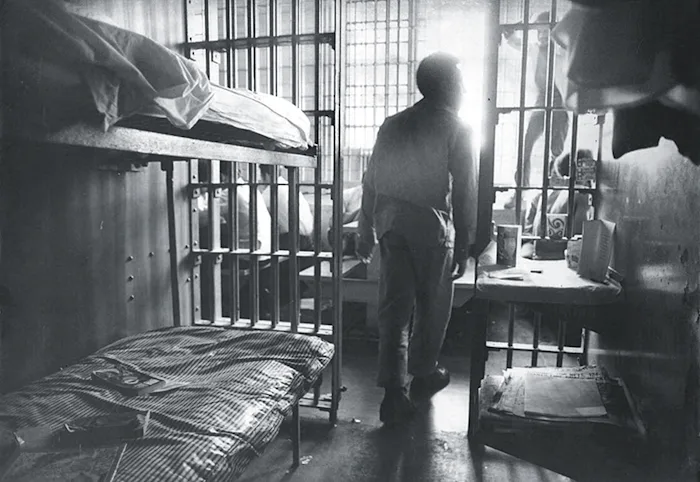

The penal colony on Rikers Island is a despicable blight on New York City, a deadly concentration of race and class violence in a network of squalid human cages. Jarrod Shanahan’s Captives: How Rikers Island Took New York City Hostage, released today by Verso, follows the development of Rikers through seven decades of class struggle in New York City and beyond. Central to this story is the way in which, through mass rebellion and escape, prisoners have consistently contested their own captivity. Given that the dangerous and dehumanizing jail system of Rikers in fact only amplifies the exploitation and oppression inmates experience on the outside, the antagonisms they generate behind bars likewise represent a continuation of the struggles that defined daily life in New York City throughout much of the postwar period.

The two passages excerpted below detail the remarkable ingenuity prisoners demonstrated in freeing themselves from the custody of the New York City Department of Correction (DOC) during a particularly acute crisis that engulfed the system in the 1970s. Together, they serve to highlight not only the acuity of struggle in the lives of many working-class New Yorkers in this period, but also the role that small groups of organized revolutionaries were able to play in promoting a culture of resistance and escape, while going to remarkable lengths to break themselves and their comrades out of jail.

Calling Their Own Plays

Amid the dramatic rise of the Black Liberation Army (BLA), a group that had drawn influence from his shootout with NYPD cops, Anthony “Kimu” White sat behind bars in city custody, held on $250,000 bail for attempted murder. In October of 1972, when White was held at the Tombs, a comrade inside named Ronald Johnson received a new pair of size-twelve sneakers from two female visitors. Sewn into the soles were two hacksaw blades. Eleven days later, Johnson, White, and five other prisoners undertook the first escape the Tombs had seen in over thirty years. In preparation, the men had sawed their way out of their housing area and covered the displaced bars with a table. Just after the 6:15am, head count, the group sprang into action. They slipped through the small opening, creeping thirty feet across a gangplank overlaying a disused area still wanting of repair since the rebellion [a year prior], before scaling a sixteen-foot wall to a small window, and once reaching it, sawing off its bars. The men then unfurled a rope made of bedsheets, down which they climbed forty feet to the street below.

The entire operation took ten minutes at the most. At 6:25, an employee of the Criminal Court Building spotted one of the prisoners descending the rope and sounded the alarm. Citing no evidence, DOC Commissioner Benjamin Malcolm and Correction Officers’ Benevolent Association (COBA) President Leo Zeferetti took turns blaming the escape on the “liberal” policies of Board of Correction (BOC)-sponsored volunteer initiatives (Malcolm) that, in bringing civilians onto the jail floor, had “allowed everyone and their brother to come and go as they want” (Zeferetti). Only later was the source of the hacksaws revealed as a routine visit.1

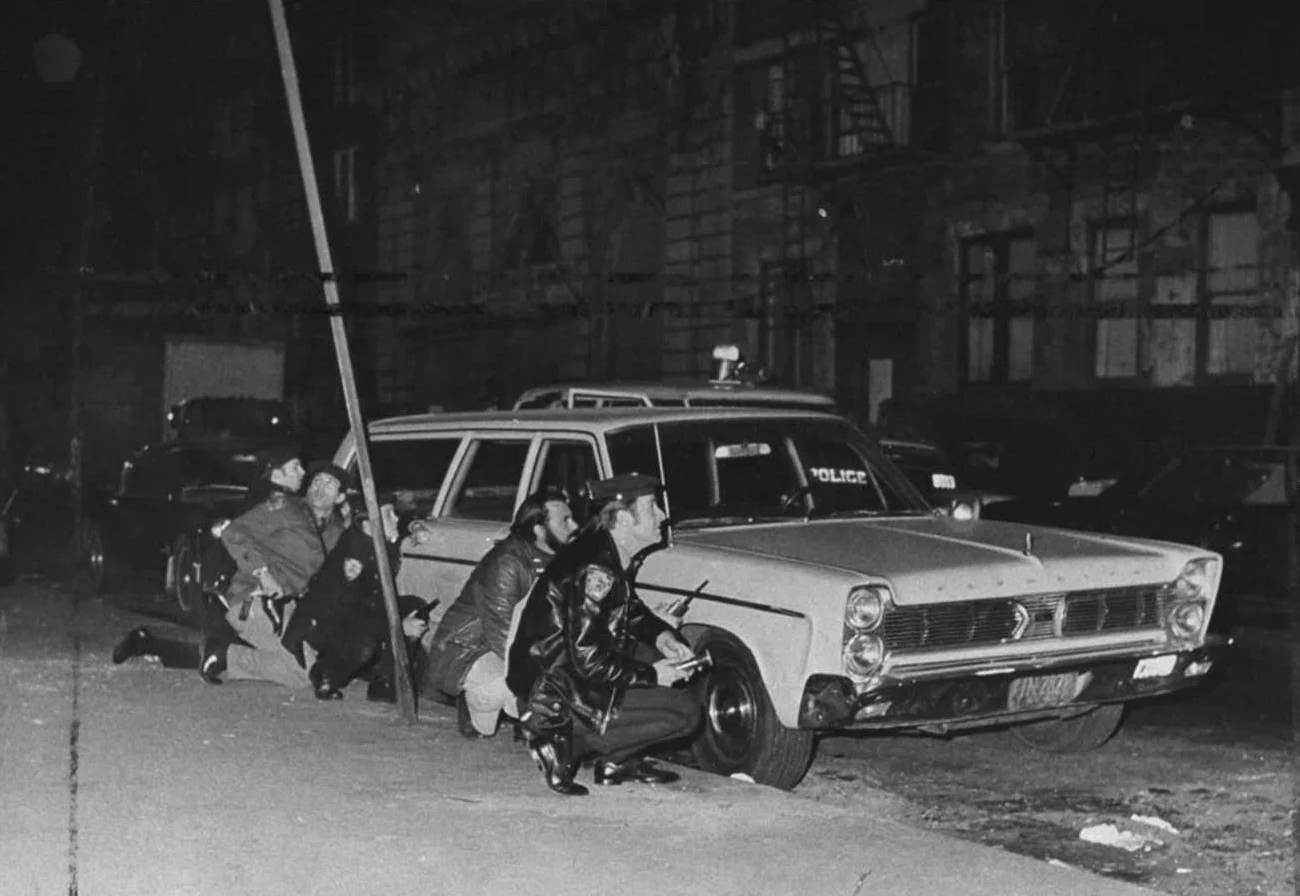

Upon his premature release, White connected with Assata Shakur, Twymon Meyers, Zayd Shakur, Melvin Kearney, and other BLA cadre whose activity revolved around bank robberies. In early 1973, White perished in a hail of police gunfire alongside his comrade Woody Green. Before the year was out, Meyers and Zayd Shakur would also be dead, felled by police bullets in dramatic shootouts, and both Kearney and Assata Shakur would be in custody. Meyers’s demise was particularly grisly. NYPD and FBI agents surrounded him on the street, riddling his body with eighty bullets. As he lay dead, a cop stood over him, firing a single shot into his head, as if to kill him a second time. NYPD subsequently held a rally celebrating his death outside the Forty-Fourth Precinct in the Bronx, while Police Commissioner Donald F. Cawley declared NYPD had “broken the back of the BLA.”2

That same year, BLA cadre Sha Sha Brown was extradited to New York City from St. Louis, where he had been arrested after a shootout with police. In St. Louis, Brown had been sentenced to twenty-five to life for the shootout, and was alleged to have planned a foiled jailbreak. Wanted in New York for the executions of NYPD cops Rocco Laurie and Gregory Foster, Brown was held at the Brooklyn House of Detention (BHD). There, he once again hatched a plan for his premature departure. In July, a sophisticated escape plan well into its final stages was discovered by BHD guards conducting a surprise shakedown. Reminiscent of White’s escape from the Tombs, Brown, his cellmate, and two prisoners in an adjacent cell had used carbonite hacksaw blades to saw their way out of their own cells and into the guard catwalk that ringed the floor, thus placing only one more set of bars — and a fifty-five foot climb down a rope they had fashioned from bedsheets — between themselves and freedom.3

Two months later, Brown was transported to Kings County Hospital for an X-ray after he complained insistently of stomach pains. In order for Brown to change into his hospital gown, he was uncuffed and shown into a three-square-foot changing booth with no room for either of the two guards escorting him. Brown changed into the gown and received the X-ray. It’s likely he was thinking all the while of the curious design of the changing booth: eight feet high, leaving a four-foot gap between the back wall and the ceiling, and fronted with a curtain that extended all the way to the floor. As the guards waited for Brown to change back into his clothing, he hopped onto the booth’s bench, scaled the wall and hit the ground running toward an exit eighteen feet away. Hearing the bench clatter beneath Brown’s feet, the guards took off after him. They were, as Malcolm later testified, no match for Brown. Based on an informant’s tip to NYPD, Brown was recaptured a week later in a BLA safe house in Bushwick, Brooklyn, along with multiple other fugitives.4

Though speed and ingenuity had abetted his daring escape, Brown had also been assisted by simple negligence typical of a department stretched to the breaking point. After discussing the escape threat posed by BLA detainees at multiple meetings with NYPD, reviewing the escape record of Brown, and learning a map of Kings County Hospital was captured in a raid of another alleged BLA safe house, DOC had enacted a protocol for monitoring the transfer of BLA prisoners like Brown. It wasn’t followed. A defensive Malcolm insisted the accounts of NYPD warnings about Brown had come from “low-level policemen” and there was no forewarning of an escape. Less explicable were the words “escape risk” and “murderer” stamped in red on Brown’s prisoner identification card, which had made the trip to Kings County with him. Moreover, DOC denied the map had anything to do with the escape. Ultimately, however, Malcolm conceded: “Any time a Black Liberation Army group wants to release a fellow Black Liberation Army inmate from a hospital they can do it. The Department is planning to establish procedures to make this impossible but the procedures have not yet been created.”

Malcolm took the rare step of suspending the guards involved, though they had by all accounts done little wrong. Brown’s case came amid a rash of embarrassing escapes, prompting Malcolm to testify “he was personally ‘fed up’ with reports showing that procedures had broken down without pointing at individuals who are at fault” — or, perhaps more precisely, with those that pointed to him. In all likelihood, the overtaxed DOC simply did not have the capacity to live up to the city’s tough talk about BLA and other militant prisoners. One investigator dubbed DOC’s uniform staff “Keystone guards,” in reference to the comically inept Keystone Cops of the silent film era. While jail administrators plead poverty and undercapacity in the best of times, during this period the New York City system was truly overwhelmed, not just by the throngs of people swept off the streets by NYPD and consigned to jail by the courts, but by the spirit of belligerence and militancy that now drove a critical mass of DOC’s captives.5

Before fleeing Kings County Hospital, Brown supposedly told guards at BHD, “I will escape, you can’t stop me.” In December of 1973, Brown had been transferred to the Tombs, along with five other men assumed to be BLA members. At dawn on December 27, a cop patrolling the area spotted two men and two women loitering around an open manhole outside the facility. They included Bernice Jones, a prominent New York Panther and widow of Twymon Meyers, and BLA cadre Ashanti Alston. Jones was alleged to be carrying a list of BLA members in the Tombs, information about their upcoming court appearances, and numerous documents about Brown. Less than two months later, and just weeks after a judge dismissed the final charges against the quartet due to lack of evidence, another group of four — two men and two women, also including Alston — handcuffed a guard in the Tombs visiting area at gunpoint and attempted to cut through the wall with an acetylene torch. Their plan failed only when the torch ran out of oxygen and they had to beat a hasty retreat.6

The cadre fled with two guards’ guns and a set of keys, the latter of which they mailed to the New York Times along with a taunting letter thanking DOC for its “cooperation,” thanks to which “you only lost your guns.” This was news to the public; an embarrassed DOC, awash in charges of “Keystone guards,” had not disclosed the missing guns, downplaying the whole incident. Deputy Commissioner Jack Birnbaum claimed DOC did not mention the missing guns “because nobody asked us.” As Public Affairs director Al Castro later complained, despite DOC’s efforts to move BLA cadre around the jail system and thwart escape plots, “the trouble is that they can pretty well call their own plays.”7

In August of 1974, with Brown back at BHD, the facility’s brand-new metal detector thwarted an attempt to smuggle hacksaw blades, allegedly intended for him, via the same mechanism that had succeeded at the Tombs: a pair of shoes. The following week, Brown, Kearney, and a third BLA cadre, Pedro Monges, fled a transport van returning them from court to BHD, after the latter stole a key. The unshackled men were able to subdue multiple guards and had begun to climb a thirty-foot fence when Brown was shot in the shoulder by a guard and dropped to the ground. Kearney surrendered, but Monges was able to breach the fence, making it a short distance before a passing police patrol unit drew their guns and recaptured him. The following May, Kearney and Monges sawed an eighteen-by-eleven-inch hole in the back wall of their cell, smashed through a plate glass window, and shimmied through an air vent, all to undertake the 128-foot descent to the ground below. Monges made it safely outside the jail gates but was quickly captured by chance by an off-duty cop. Kearney was even less fortunate. As he descended the makeshift rope, it broke suddenly, and he fell to his death. DOC later alleged that Brown and another BLA cadre, Roderick Pearson, were seen running back to their cells shortly after the rope snapped.8

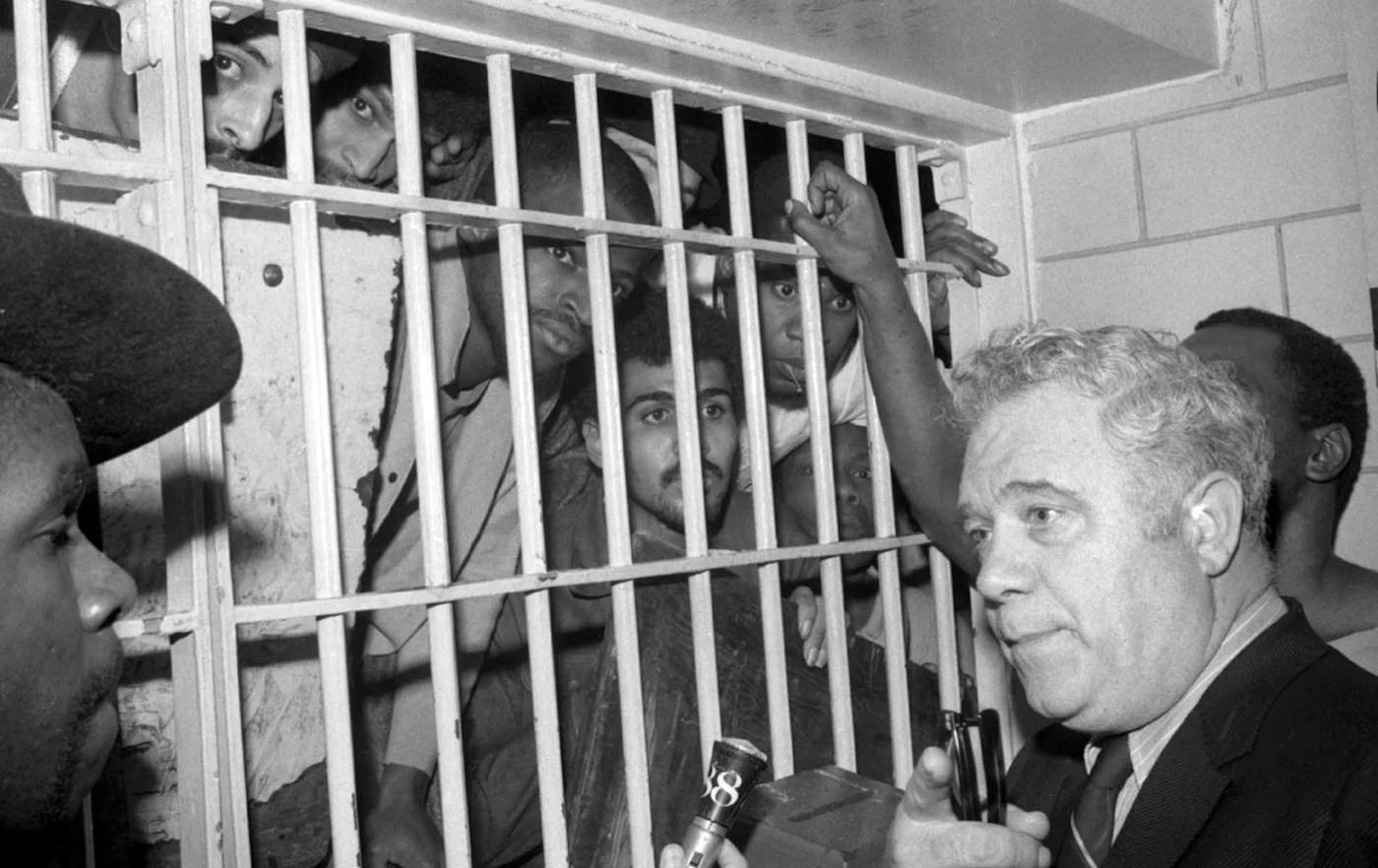

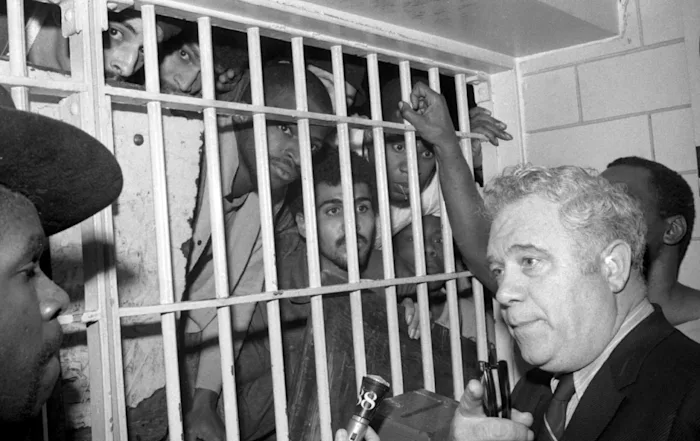

In early 1975 a maximum-security block at Rikers Island’s House of Detention for Men (HDM), home to eleven accused BLA cadre, was the scene of another dramatic escape attempt, the failure of which was surely not due to lack of imagination or daring. It began when BLA member Herman Bell, on his second trial for the shooting of NYPD officers Piagentini and Jones, asked a guard to use the phone. When the guard appeared with the phone, DOC officials later claimed, Bell pushed him against a metal-grated wall and held a sharpened stick to his neck. Another prisoner grabbed the guard’s keys, and the duo tied him up and placed him in a nearby cell. Next, they lured another guard into the cellblock by complaining of a broken television, and he too was tied up and placed in a cell. Fourteen prisoners, including the eleven BLA cadre, held the block unchallenged for almost an hour while attempting to saw through a barred window with hacksaw blades.

The escape was foiled when a passing guard noticed the men sawing. Evidently deciding on the futility of the effort — and apparently seeing no use in the cellblock occupation tactic as an end in itself — the prisoners surrendered their hostages and returned to their cells. NYPD claimed the escape was part of an elaborate seaborne rescue in which armed BLA cadre set sail in three rafts from the Tiffany Street Pier in the Bronx, at least one clad in scuba gear, headed for the facility. After receiving a report of the flotilla, the harbor patrol had discovered an abandoned raft, which the cops claimed contained ammunition and a map of HDM. The East River current, it seemed, had foiled their mission. Asked at a BOC meeting how hacksaw blades got into HDM, Director of Operations D’Elia replied that a broken window had recently been discovered in a visiting booth. Seeking, as DOC and COBA officials often do, to minimize the role guards play in smuggling contraband into its facilities, D’Elia “declared that these inmates are clever people who can estimate when they will not be searched and thus will be able to sneak contraband into the institution.”9

It is worth emphasizing that the black and brown revolutionaries of this period by no means held a monopoly on ambitious attempts to free themselves from DOC custody. In fact, some of the civilians proved just as adept at hatching bold escapes as the professional revolutionaries. In 1975, prisoner Joseph James reported to Kings County Hospital for a dental appointment and ducked into the bathroom, where a coconspirator had left him a gun. James opened fire in the crowded hospital, killing guard George Motchan and injuring another guard and a patient. Shortly before Bell’s foiled escape, a group of prisoners at HDM discovered that the liquid in the facility’s Xerox machine, when ignited, could melt the glass on windows to the outside, allowing it to be noiselessly ruptured using a rag mounted on a stick. Working quickly and quietly, the four were able to create a big enough hole to climb through undetected. Getting off the island, however, proved more difficult, and they were soon recaptured.10

In the month of May 1974 alone, at least fourteen prisoners with no established connection to BLA escaped from three different DOC facilities, including Rikers. Among them were four prisoners at BHD who accomplished what had eluded Brown: sawing through the bars of an eighth-floor dayroom, they successfully descended a rope made of blankets and twine. Recaptured prisoners later claimed to have obtained the saw blades from a guard for fifty dollars, as part of an elaborate smuggling operation. This led to the indictment of four civilians and five guards, and a security crackdown that catalyzed a hunger strike at BHD. A mere four days after this BHD escape, nine prisoners at Rikers Island pried open a window and fled into the night. One was apprehended on the island, but three swam to an anchored tugboat and, wielding a knife, obliged the seven-man crew to drop them off on the Tiffany Street Pier in the Bronx. They were captured shortly thereafter, clad in yellow seafarer outfits pilfered from the vessel. Later that month, a prisoner at Branch Queens sawed his way through the bars, climbed down forty feet, then traversed a twenty-foot wall to freedom.11 [...]

Patron Saint of Prison Breaks

Looking back on 1977, BOC recalled ruefully that the year “will be remembered as a year of many escapes from Rikers Island,” totaling thirty-five successes, to say nothing of attempts. These pushed the total of escapes from DOC custody since 1974 to 153. A steady stream of hacksaws winnowed its way into Rikers jails, enabling multiple exoduses, including from the maximum-security area of HDM reserved for prisoners deemed escape risks. According to DOC, in one case blades were smuggled into the jail concealed inside fully functional ink pens, which family members had given prisoners in court. Purportedly, these pens were capable of passing a basic contraband test, by which the prisoner was made to uncap the pen and write with it, to prove it contained an ink cartridge. For reasons that will soon be clear, however, it is a story to be taken with a grain of salt.

As DOC facilities crumbled and teemed, prisoners increasingly escaped in large groups, sometimes as many as eight at a time, by cutting their way out of HDM and other facilities. As in the early 1970s, these escapes demonstrated not only familiar patterns, but also featured a recurring cast of prisoners who at once rejected the authority of DOC and undertook ingenious attempts to proactively free themselves from its custody. Their efforts challenged not just the power of the jail system, but the authority derived from politicians, like Mayor Koch, who based their fiscal austerity on their supposed ability to keep lawbreakers behind bars.12

In 1977 three adolescents locked up at the Adolescent Remand and Detention Center broke free, crept to the guards’ parking lot, commandeered a guard’s car, and successfully drove straight off the island, past multiple checkpoints, to the freedom of suburban Queens. In response to this embarrassing breach of security, DOC hastily claimed the young men had undertaken a sophisticated — and highly cinematic — jailbreak, complete with meticulous timing of guards’ comings and goings, and even counterfeit badges to get past the checkpoints. It was a compelling story. But there was one problem.

“There was no evidence to sustain that story,” BOC concluded. “What was known at the time the Department was being quoted [in the press, about its imaginative version of the escape], is that the inmates took advantage of two inattentive correction officers who simply weren’t doing their jobs.” Three years later, a trio of prisoners pulled off a “carbon copy” of this escape, leaving a hapless guard’s car at John F. Kennedy Airport for investigators to discover the following day. Less successful but no less bold were a group of twenty-four prisoners who took over a transport bus moving them between Rikers facilities and attempted to drive it off the island. Their plot was foiled when the driver crashed the bus. Foregoing the bridge altogether, a quartet of prisoners inflated trash bags into makeshift rafts, greasing themselves and the bags with Vaseline to stay afloat. The bags proved insufficient to the task and burst, but one of the four nonetheless made it across. Subsequently, a pair of Rikers prisoners concealed themselves in a truck delivering stale bread to the Flushing Meadows Zoo. The duo’s disappearance was only detected by the driver, whom they startled by hopping off the back of the truck on Grand Central Parkway and vanishing into the freedom of the Queens night.13

Rikers was not the only place DOC prisoners deemed worthy of escape. In 1980, a famed horse trainer and Upper East Side socialite named Howard “Buddy” Jacobson, held at the Brooklyn House of Detention following a murder conviction, received a visit in the facility’s counsel room from a man purporting to be his lawyer. During this visit, the men swapped clothing and identification. Jacobson then tapped on the door, announced the visit had ended, flashed his supposed lawyer’s credentials, and strode out the front gate of BHD to freedom, leaving the latter, apparently well-compensated for the ruse, to face charges for abetting escape.

In early 1982, a group of six prisoners in the south wing of the sixth floor of the Bronx House of Detention overpowered the two guards overseeing their cellblock, bound them, and placed them in the dayroom while attempting to saw through a window with hacksaw blades. One guard managed to set off his emergency alarm before being overpowered, but when the control room called, a prisoner answered, posing as a guard, and reported a false alarm. A third guard appeared shortly thereafter; welcomed inside by a prisoner dressed in a captured guard’s uniform, he was also taken hostage. The plot was at last detected when the guards on duty did not respond to calls for a coffee delivery. The tour commander responded in haste, flanked by a small squadron of guards who foreswore riot gear, rushing to the scene so quickly they forgot the keys to the tier’s gate. Once inside, they fought the prisoners with their clubs, viciously beating the rebels in a manner BOC found “completely disproportionate to the circumstances.” There were no consequences for the guards.14

This wasn’t the most spectacular escape attempt that year— or even that month. Less than two weeks later, ten prisoners in transit at the Brooklyn Supreme Court escaped leg irons and handcuffs to overpower three guards, one of whom provided them with a gun that a fleeing prisoner used to carjack a motorist, shooting the motorist in the process. In a scathing 1982 report to the mayor and city council, BOC concluded that, “despite the image of prisoners furtively digging tunnels or quietly sawing through bars to escape, prisoners are more likely to escape by recognizing and taking advantage of lax or poorly trained personnel and inadequate or loosely enforced security procedures.” For his part, the studious Ward attributed the rash of escapes to several factors. The erection of the Rikers Island Bridge, he reasoned, had slowed the East River current; the extension of the LaGuardia Airport runway provided an attainable goal for swimmers; and an increase in detainees meant an increase in smuggling, since they had more visits than sentenced prisoners. Moreover, technology had advanced, bequeathing better jailbreak tools such as smaller and more powerful saw blades. DOC’s Joseph D’Elia was markedly more defensive, telling BOC, “An escape is made on an officer, not on a system.”15

One escape of this storied period stands out so spectacularly that it prompted artist David Wojnarowicz to immortalize its protagonist as “William Morales, Patron of Prison Breaks.” Part of the diminished, but by no means vanquished, revolutionary underground, William Guillermo Morales manufactured bombs for the Puerto Rican Armed Forces of National Liberation (FALN), who fought for an autonomous Puerto Rico. Morales and his comrades in FALN had operated under the radar for years, detonating over one hundred explosive devices throughout the mid to late 1970s, without a single member being arrested. On July 12, 1978, a bomb Morales was manufacturing in a house not far from Rikers Island detonated prematurely. The blast destroyed Morales’s hands and mutilated his face. Badly burned, maimed, bleeding profusely, missing one eye, and virtually blind in the other, Morales managed nonetheless to flush a number of incriminating FALN documents down the toilet before the police arrived. He then filled the apartment with gas, hoping to blow himself up along with the cops. Instead, Morales was captured. Despite his grave condition, he managed shortly thereafter to tell a NYPD detective, from beneath layers of bandages, “Fuck you. Fuck yourself.”16

In April of 1979, after Morales had been held for over a year at the prison ward of Bellevue Hospital, he was convicted of weapons charges and sentenced to twenty-nine to eighty-nine years behind bars. Prior to sentencing, Morales remarked, “They’re not going to hold me forever.” One month later, this prediction was borne out. Morales managed to get hold of a pair of fourteen-inch wire cutters, which NYPD suspected his attorney smuggled to him, though she was never formally charged. With the help of a fellow prisoner, Morales subsequently affixed these cutters around his waist using shoelaces, so that they dangled beneath his bathrobe. Over the course of the next two nights, despite having lost his hands and much of his sight, Morales cut a small hole in the metal grating covering his window. He then punched through the outside screen, produced a rope made of bandages, and began his descent from his third-floor room, some forty feet in the air.

Waiting on the ground below were more than a dozen cadre from the remnants of the Black Liberation Army and the Weather Underground. The bandage rope apparently failed, sending Morales tumbling to an air conditioner unit that broke his fall, and then onto the grass below. His comrades whisked him away to a New Jersey safe house, from which he later made his way to Mexico, then Cuba, where he lives today as a free man. A mortified and enraged Commissioner Ciuros, ridiculed for the escape of a handless man from DOC custody, pursued a slew of administrative charges against sixteen guards and captains responsible for every conceivable failure leading to the escape. The story became less about the tenacity of the enduring revolutionary underground and more about the latest fiasco for DOC’s Keystone guards.17

Jarrod Shanahan’s Captives: How Rikers Island Took New York City Hostage, is out now with Verso Books.

Notes

1. Bryan Burrough, Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence (New York: Penguin, 2015), 192; Lacy Fosburg, “7 Saw Their Way Out of the Tombs,” New York Times, October 24, 1972; Glenn Fowler, “Two Accused of Smuggling Saws to Tombs Escapers,” New York Times, February 7, 1973.↰

2. Borough, Days of Rage, 210–17, 237–42; Judith Cummings, “2 of 3 Black ‘Army’ Suspects Are Held without Bail,” New York Times, September 19, 1973; Michael T. Kaufman, “Woman Captured in Shoot-Out Called ‘Soul’ of Black Militants,” New York Times, May 3, 1973; Michael T. Kaufman, “Slaying of One of the Last Black Liberation Army Leaders Still at Large Ended a 7-Month Manhunt,” New York Times, November 16, 1973; Safiya Bukhari, “Lest We Forget,” in The War Before (New York: Feminist Press, 2010) 150–1.↰

3. Glenn Fowler, “Brown Is Recaptured with Four in Raid on a Brooklyn Tenement,” New York Times, October 4, 1973; Alfred E. Clark, “Jail Escape Is Foiled, Officials Report,” New York Times, July 28, 1973.↰

4. Board of Correction (BOC) Meeting Minutes 10/2/73, 7–9; Fowler, “Brown Is Recaptured.”↰

5. BOC Meeting Minutes 10/2/73, 7-9, quoted text is a paraphrase in the meeting minutes; Fred Feretti, “Beame Orders an Investigation of Jails, Covering Escape and Bribe Charges,” New York Times, March 7, 1974.↰

6. Pranay Gupte, “Suspect in Slaying of 2 Officers Flees,” New York Times, September 28, 1973; Paul L. Montgomery, “4 Seized Near Manhole in Alleged Plot to Free Black Army Friends in Tombs,” New York Times, December 28, 1973; Feretti, “Beame Orders an Investigation”; Dan Berger, Captive Nation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014) 249n77; “3 in an Alleged Plot to Free 6 at Tombs Released by Judge,” New York Times, January 24, 1974.↰

7. “Times Receives Key Set Stolen in Tombs Break In,” New York Times, May 7, 1974; Max H. Seigel, “4 Others Linked to Prison Escape,” New York Times, May 28, 1975. ↰

8. “New X-ray Machine Foils Blade-Smuggling at Jail,” New York Times, August 7, 1974; Alfred E. Clark, “Brooklyn Escape by 3 Is Thwarted,” New York Times, August 16, 1974; Robert McG. Thomas, Jr., “Fleeing Prisoner Falls to Death, 2d Inmate Captured in Brooklyn,” New York Times, May 26, 1975; Seigel, “4 Others Linked to Prison Escape.”↰

9. BOC Meeting Minutes 3/3/75, 7; Robert D. McFadden, “Rikers Escape Attempt Reassessed as Stronger,” New York Times, February 22, 1975; David Bird, “Police Investigate Apparent Escape Attempt by Black Liberationists,” New York Times, February 18, 1975.↰

10. Alfonso A. Narvaez, “Prisoner Shoots 2 Guards and Patient and Flees from Kings County Hospital,” New York Times, September 10, 1975; BOC Meeting Minutes 3/3/75, 6.↰

11. Robert D. McFadden, “15-State Alarm Issued for 2 Fugitives from Brooklyn’s House of Detention,” New York Times, May 5, 1974; Robert Hanley, “Injured Fugitive Held in Brooklyn,” New York Times, May 6, 1974; Robert Hanley, “Rikers I. Fugitives Commandeered a Tug,” New York Times, May 7, 1974; Nathaniel Sheppard Jr., “Captured Inmates Report Paying Officer for Saw,” New York Times, May 8, 1974; Wolfgang Saxon, “Prisoner Escapes from Queens Jail,” New York Times, May 26, 1974.↰

12. BOC, Annual Report 1977 (New York: BOC, 1970), 25; BOC, Annual Report 1980 (New York: BOC, 1980), 11–12; Joseph L. Jacobson, “Escape of Eight Inmates from Maximum Security Section, Block 1B of the N.Y.C. House of Detention for Men—September 24, 1979,” Edward Koch Papers, Box 112, Folder 8, LaGuardia/Wagner Archives at LaGuardia Community College (LWA). ↰

13. BOC, 1977, 25–6; BOC Meeting Minutes 3/5/80, 1–2; BOC, Report to the Mayor and the City Council on Safety and Security in New York City’s Jails (New York: BOC, 1982), 8.↰

14. Benjamin Ward, “Escape of Howard ‘Buddy’ Jacobson,” June 17, 1980, Koch Papers, Box 112, Folder 9, LWA; BOC, Safety and Security in New York City’s Jails, 3–4.↰

15. BOC, Safety and Security in New York City’s Jails, iv–v, 2; Benjamin Ward, “Rikers Island’s Future,” New York Times, April 19, 1980; BOC, Draft Meeting Minutes 2/22/77, 2, quoted text is a paraphrase in the meeting minutes.↰

16. Burrough, Days of Rage, 461–4.↰

17. “Morales Is Sentenced to 29-Year Minimum on Weapons Charges,” New York Times, April 21, 1979; Boroughs, Days of Rage, 471–4, 544–5; Robert McG. Thomas Jr., “16 in Correction Post Accused of Negligence in Escape by Morales,” New York Times, December 17, 1979.↰