Fascism and the Spectacle of Death

Ian Alan Paul

Other languages: Türkçe, Français, Español, Ελληνικά

I

Wealth above, and death below: in recent history this arrangement has proven to be remarkably tolerable. Everyone of course is aware that ever more people are immiserated and discarded, that ever more of the Earth is destroyed. But for the better off, the very worst is kept at a very comfortable distance, and life more or less maintains its rhythms. Guards and maids arrive as scheduled to patrol and clean, investment portfolios flash to life and fall to rest as global markets open and close, and Amazon packages show up on doorsteps miraculously, in only hours. Misery, suffering, and death do enter into view, and at times there is even the lingering sense that this life may only remain possible because of the way those lives continue to be depreciated and at times disposed of, but it all appears to stay quite removed and detached, shining always on the other side of the screen.

For those who live below, however, it isn’t so possible to separate oneself so completely from what lays waste to the world. Insecurity, poverty, and mortality all incessantly wash across the shores of everyday life here at the bottom, arriving as debt, or as heatwaves, or as the police, steadily corroding what little stable ground remains. As what makes life livable and worth living grows ever more expensive and runs in ever shorter supply, the highest aspiration can often be to delay the arrival of the worst and remain hanging on by a thread. While distractions remain endlessly updated and for all practical purposes inexhaustible—an influencer posts a selfie from a war zone, an online brand shares a collection of AI generated ads, another politician makes another Nazi salute—none can fully numb the sense that life is increasingly lived only as the fragile foreground of a landscape whose background grows thick with death.

All throughout our world the same lethal calculus is at work: on one side of the formula is the accumulation of wealth, and equated with it on the other side is the desolation of life. The few at the top hoard ever more riches and command ever more power, while the many at the bottom are compelled to work, are beaten down when they step out of line, and eventually are made redundant and tossed away, just as private gardens remain carefully tended to by groundskeepers as vast rainforests show the first signs of irreversible collapse. While the bleak costs of this arrangement have been paid almost exclusively by those who have been condemned to live in society’s lower strata, today no one remains fully sheltered from or blind to the catastrophe which piles ruin upon ruin and digs grave upon grave without pause. Seeing diverse forms of violence being dealt out ever more liberally and generously on their screens, the wealthy rush to retreat into ever smaller enclaves lined with ever higher walls, surrounded on all sides by ever more abandoned places and people, hoping to hide themselves and their fortunes from the world that capitalism has blighted so totally. Those with lesser means, increasingly exposed, vulnerable, and imperiled, build whatever makeshift rafts they can and exhaust themselves in a struggle not to drown.

The degradation of life has saturated society so completely that it now appears as just another unremarkable feature of the scenery, entirely predictable and completely accounted for in advance, widely documented and circulated for all to see, glued like decorative wallpaper onto the inside of every eyelid. In a society whose common sense involves the perpetual degradation, devaluation, and destruction of the living, no one bothers anymore to deny or dissimulate the reality that child laborers are buried among the cobalt they dig from the earth by hand, that families of migrants collapse and die at the border beneath the desert sun, or that distressed and depressed workers jump from the upper story windows of iPhone assembly plants. The affluent and the impoverished alike swipe between videos of military jets bombing refugee tents, of riot police spraying chemical weapons into crowds, and of people being dragged off the street and sent to camps, all of which serve as high resolution reminders of just how superfluous and disposable capitalism has made life to be.

At the foundation of class society is an ever wider separation between worlds constructed to protect, nourish, and enrich life and worlds constructed to exploit, subordinate, and dispose of it, and yet across all of these worlds there is a consensus that whatever remains of the good life now has as its foundation only the seemingly limitless devaluation of life and the Earth as a whole. Even those who live in the luxury high rises of the metropolis, blanketed within layers of advanced surveillance systems, smart domestic appliances, and armed private security, now nonetheless find that they must step over people sleeping on the street each morning as they head out to start their day. Among the enduring contradictions of class society is that its sharply divided worlds nonetheless exist in the same world, and as a consequence whatever wealth is amassed can never be absolutely removed or completely isolated from the amassing violence and destruction required to produce, sustain, and defend it. The world is separated ever further into worlds for living and worlds for dying, and yet the desolation that follows from this separation steadily accumulates until it determines the ambient conditions for all existence.

The true poverty of our society isn’t that it so willingly destroys the Earth and desolates the living, but that it has atrophied to the point that it can no longer imagine being any other way. Politics and economics have now entered their terminal phase and have shown themselves to be completely exhausted of all possibility, remaining capable only of imposing harsher controls upon and extracting the final profits from a world which they continue to reduce to a wasteland. The fact that progress is a catastrophe now appears entirely sensible and prosaic, giving a wholly ordinary appearance to the ongoing history of economic development and growth that is also the ongoing history of the eradication of the indigenous, the subjugation of workers, the policing of racialized and sexualized others, the destruction of the Earth, and the multiplication of death. Emerging within the rubble of this political and economic impasse, the most expedient and profitable way of ensuring that society’s accumulation and desolation continue to develop ultimately begins to take shape in cultural means, in a set of forms and techniques which aspire to take power over death by taking power over its appearance, by grasping death as an image.

When capitalist society objectifies death as online photos, videos, and many other visual forms, it gives it the semblance of being just another possession which can be looked upon and consumed when desired, circulated or exchanged in this or that way, and then disregarded and cast aside as needed, even as death itself multiplies ever more widely and with ever fewer inhibitions. The capitalist separation of the world into worlds is thus formally doubled as the cultural separation of death from its mere appearance, abstracting and objectifying it in ever more spectacular forms. Just as the endless flow of disposable commodities are reflected in the disposability of the workers who produce them, the disposability of life in general is now reflected in images of death which can just as easily be scrolled past, refreshed, monetized, tracked, deleted, and done away with. Capitalism’s formal organization of death’s appearance brings it into view fleetingly, beheld as rapidly as it can be expelled, rendering it formally equivalent with the plastic shopping bags which are used for a moment only to be abandoned everywhere as litter, coating the sides of highways and choking the branches of trees. There is no longer any need to repress death when it can be culturally recuperated in this way, when it can be made ever more sensual and brought fully into view in easily consumable and conveniently disposable forms.

The escalating violence which is at the foundation of class society, all of the accumulation which desolates and desolation which accumulates, inevitably begins to coagulate and create the historical conditions for a more unsparing and severe situation to emerge. As it becomes increasingly difficult to make sense of living in a world premised upon such immense dying, as people cannot so effortlessly blot out the experience of the death which accretes so abundantly all around, another way forward is glimpsed in fascism, that form of society which is premised upon the reorganization of all social life on the basis of death, intensifying a passive indifference towards death such that it begins to transform into an active desire for it. Always already residing as a latent potential within the history of capitalism, fascism unfolds in culture as an expanding aestheticization of annihilation, cultivating a society which is ever more captivated by images of its own desolation, inviting everyone to search for new ways of life in spectacles of death.1

II

Built in the Palacio Cervelló in Barcelona’s historic center, the MOCO Museum opened in 2021 as the latest extension of its other branches in Amsterdam and London. Art by Banksy, Marina Abramovic, and Takashi Murakami hangs on the walls, ambient electronic music plays through speakers hidden in ceilings, and LED screens cycle through NFTs produced by Beeple, Paris Hilton, and JR. Walking through the museum, it’s apparent that it was designed as a space not for viewing artwork so much as for taking selfies with it, staged and optimized in every way to be seen and captured through a smartphone’s lens. Immersive installations are constructed in long hallways so that everyone can snap a picture of themselves reflected individually in the mirrored walls surrounded by points of colorful light. Large scale paintings and photographs are strategically distributed throughout sectioned off galleries, ensuring no one accidentally walks into or obstructs one another’s shots. Each image taken in the museum and then shared online is simply another way of affirming what has come to be the spectacular truth of social life: I appear therefore I am.

While it’s easy to disregard the MOCO as being just another vapid manifestation of the war of gentrification being waged against the city, that would risk missing the way in which places such as these are where capitalist culture now unfolds in its most historically developed and advanced form. Culture is no longer at all concerned with expressing concepts or even representing anything visually, but rather directs society to formalize itself first as an image. In our time, reality not only appears in ever more diverse fashions but also comes to be organized by, subordinated to, and ultimately experienced as the sum of its appearances. Very little escapes this spectacular recomposition of the world, as everything from the most ordinary to the most jarring aspects of society come to be structured as images in advance. Factories, warehouses, and fast food chains are redesigned so that employees’ gestures remain exposed to the oversight, analysis, and optimization of surveillance systems, intimate relationships evolve in relation to their perennial visualization on online platforms, and immigration agents make sure the lighting is just right before they break down a door and drag people away into unmarked cars in front of film crews. As history unfolds on screens, the appearance of the world everywhere prevails over the world itself.2

Nowhere is this more apparent than in figures such as Donald Trump, who craves only to appear ever more widely and in ever more numerous forms. Just after a bullet missed tearing through his skull by a centimeter, Trump’s only thought was to pose for the cameras with his fist raised, to become an image, and even if he had been killed Trump would have been the first to appreciate the astonishing sight of his own assassination. His political ascendence and the whole logic of his administration have been built entirely on this spectacular foundation of images, as even the people who have been given control of the economy, the healthcare system, the spy agencies, and the military were all selected because of how they appear on television. While many political commentators have made careers out of psychoanalyzing Trump and speculating about his hidden motives, nothing in actuality remains concealed beneath the surface. Trump is what a life looks like when it has vacated itself of all interiority and has exposed itself completely, desiring only for every naked detail to be seen in its totality, forever, by all.

As reality has been made secondary to its visuality, a profusion of spectacles has invaded social life which function to organize society by organizing society’s appearance. When Walter Benjamin began to theorize cinema in the early 20th century after he had fled from the Nazis to France, he lamented that the automatic succession of images projected on the screen diminished the capacity to have a critical relationship to them. While it remained possible to stand at a distance from a painting and contemplate it, allowing one’s attention to move between its various formal elements and have an internal movement accompany it in thought, cinema’s rapid projection of individual frames made it no longer possible to “think what I want to think” as thought itself was “replaced by moving images.”3 Just as mass produced commodities completely reshaped every dimension of social life, the mass production and dissemination of images ultimately provided the cultural means of reshaping the formal terms under which capitalist society could be thought and perceived.

Benjamin saw cinema as a means of producing and distributing experience, of organizing sensuality itself in parallel to capitalism’s organization of industry. The space and time of perception could now be technologically reformalized and reorganized, using montage to cut apart and then stitch back together disparate scenes and moments just as capitalism’s global expansion had comprehensively separated the world only to reunite it as separate, extending the economic means of production and distribution to the production and distribution of the sensible.4 Such a technological and historical development ultimately crashed into society with a severe and total force, spreading metaphysical wreckage and debris everywhere in its wake, splintering reality into ever greater numbers of appearances which are perpetually reconstructed into an ever more spectacular real. Benjamin in the end feared that cinema would serve as a dangerous accomplice of fascist movements who sought to weaponize this “perception that has been changed by technology,” to reshape social life by inundating it with images, and in this way to further cultivate and substantiate a society premised upon the endless multiplication and aestheticization of domination and death.5

In our time the subordination of the world to its appearance has historically developed into a far more advanced form, utilizing digital technologies which are designed to cultivate a visuality without limits. Images can now be produced, distributed, and consumed anywhere at all by simply pulling out a phone, and while projected films have a finite duration there is no constraint to the amount of time you can remain mesmerized in front of a digital screen as an infinite sequence of content is seamlessly delivered online. While cinema was formalized as the mass production of images for the masses, our digital technologies have produced a sensual order which simultaneously atomizes and totalizes: each individual produces their own images and has their own personalized stream of images delivered to them, just as reality itself has flattened out into a screen the size of the world.6 While Benjamin saw that thought was at risk of being replaced by images, under present conditions it is also threatened by algorithms that oversee the online production, dissemination, and consumption of the visual, ensuring images remain increasingly integrated into and increasingly inseparable from every moment of life, making existence itself ever less discernible from its appearance. Society everywhere takes on a streaming form, making every aspect of itself as immediately accessible as it is eminently superfluous: images are streamed from datacenters to screens, products are streamed from foreign factories and distribution warehouses to homes, and lives are streamed to perform various tasks assigned by gig apps as the whole world comes to be circulated and organized as an accumulation of appearances online.

As all of reality undergoes this spectacular transformation, images come to be as ubiquitous as they are transitory, as accessible as they are discardable, as essential to social life as they are made to be essentially equivalent to one another thus of little to no worth. The disposability of images thus follows the same formal logic as the disposability of commodities, which is also the disposability of life, which is also the disposability of the world. Images flash across screens and then vanish as they’re scrolled past, just as smartphones are rapidly made obsolete and thrown in the trash as each subsequent version is released, just as workers are effortlessly fired and replaced when they are injured or made obsolete, just as the desolation of one region of the Earth due to destructive farming, logging, fishing, or mining simply means that it’s time to reallocate investments and bulldoze across another. Capitalism takes form historically as this collective suicide pact, subordinating all of the world to the economy’s thirst for infinite accumulation and in so doing integrating all of the world into the process its own infinite destruction. Everything is compelled to function, to be realized as value, to work for the economy and thus to be exhausted and eventually depleted by it. In the shadow of capitalism’s accumulation of wealth is the accumulation of ever greater volumes of disposable images and commodities, a form of production which also produces a world in which everything, including life and death, is made just as disposable.7

When Benjamin theorized the technological transformation of culture, he focused in particular on the destruction of the artwork’s aura, its unique and situated existence, its specificity and singularity. A painting carries its history with it, materially reshaped by the places it’s been exhibited, how it’s been preserved and cared for, and which hands it’s passed through. A photograph of a painting however explodes this formal logic when it is mass produced, spreading out its existence across a multiplicity of divergent contexts, each of its copies being more or less interchangeable with every other. Capitalism’s transformation of death into an image functionally eradicates its singular existence in this same technological churn, reducing it in such a way that it becomes indistinguishable from the Guernica postcards sitting in museum gift shops or the barrels of crude oil moving through supply chains. In life there is perhaps nothing as singular as death, as that immeasurably dense moment in which our form gives way to another, and yet capitalism denies death of its singularity by rendering it ever more commensurate and fungible, capturing it ever more comprehensively within its circuits of consumption and exchange. Just as capitalism remains dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt, and yet takes on the appearance of a glossy package sitting neatly on a store shelf, the death produced by capitalism comes into view in ways which are formally separated from its reality so as to facilitate its effortless consumption. Capitalist society disposes of life and in so doing brings death upon it, only then to further dispose of death.

The capitalist subordination of the world to its appearance depends upon a spectacular procedure which invites people to perceive the world from the perspective of capital, and thus to value and take pleasure in all of the ways capitalist society brings death upon the world. As the economy’s continued expansion relies upon and necessitates expanding forms of destruction, death itself ultimately emerges not simply as detritus to be pushed to the periphery or buried beneath the surface but rather comes into view simply as another object of the aesthetic economy, as another arresting and commodified appearance to behold. Images of death thus come to be consumed casually or at other times passionately, either providing a fleeting emotion or giving form to intense fantasies, but in every case death is approached as simply another product of capitalist society. It is under these historical and cultural conditions that fascism can not only begin to take root but can thrive, germinating throughout a society where ways of seeing have entirely converged with ways of being, drawing life to organize itself ever further around death by ever further welcoming death as an image.8

What is involved in submitting to a fascist culture, in embracing and living a fascist life? Above all else, it requires becoming enamored with the view that some people are meant to live while others are meant to die, grasping life and death simply as they appear as complementary entries in capitalism’s balance sheets, and ultimately in literally seeing lives in this way. The economic division between affluence and poverty which is the foundation of class society thus also takes form as a sensible division between lives which are perceived to be of worth and lives which are perceived to be worthless, aesthetically shaped by the desolation which is inherent in the total economization of life and death. A fascist takes the same cheap joy in each new purchase as they do when they view a person being trampled upon, both of which appear as part of the common sense of capitalist society which constructs life only on the basis of the multiplication of death. At the very heart of fascism is a dream of achieving a total synthesis of capital and life, a dream of ensuring that capitalism determines not only the form of the economy and of politics but also the form of all possible meaning, desire, and experience, a dream of producing a society in which what is desired is not only accumulation but also desolation. This is the true depth of the catastrophe: life is relentlessly degraded and disposed of, and yet lives nonetheless come to be attracted and attached — sensually, aesthetically, subjectively, libidinally — to ever more dazzling forms of destruction which are perceived to be synonymous with social life itself.

To see the world as capital does involves seeing the ongoing desolation of life as the foundation of further accumulation, and thus involves seeing value in the humiliation, subjugation, and death of others. In an AI generated video posted online by Trump in the first weeks of his second term, scenes of children wandering through the ruins of Gaza are followed by scenes of crowded nightclubs, luxury yachts anchored off of pristine beaches, and expensive sports cars framed by glistening shopping districts. Viewed and shared by millions online, it’s necessary to understand that the genocide in Palestine took place so that these kinds of images could become real, inviting viewers to take pleasure in the appearance of a resort built on top of mass graves, in the sight of luxury and wealth arising from obliteration and desolation, in a spectacle of death whose aesthetics are derived from the devaluation and destruction of those buried beneath the rubble. As life and death are captured within capitalism’s aesthetic economy, people come to be seduced by the view that survival, pleasure, and flourishing here is necessarily equated with misery, suffering, and extermination there, that life is sustained and given meaning not only by capitalism’s productive forces which supply an endless stream of commodities but by its destructive forces as well which dispose of what has been made worthless. Just as the dark shades of a vignette produce the appearance of a bright and luminous center, fascism invites everyone to see not only the possibility but also the beauty of their own life in the death of others, and in this way to see the death of others as beautiful.

Fascism’s spectacles formalize death as an image ultimately so that it can be made actual by being made to appear. As migrants have been swept off of the street, dragged onto deportation flights, and thrown into El Salvador’s concentration camps, drones and camera crews accompanied each step of the process so that this degradation and subjugation of life would be coupled with its visual production, both making a spectacle of society’s domination and dominating life in a spectacular form, further entrenching a fascist culture which embraces death so that capital can live. Israeli soldiers stage proposal videos surrounded by the lethal horror they’ve unleashed in Gaza, and the United States’ Secretary of Homeland Security poses in front of bunks of prisoners with shaved heads in a form which visually references the Nazi’s extermination camps. Images of life are coupled with images of domination and death in order to further realize the separation between those perceived to be worthy of life and worthy of death, and ultimately to make this separation itself the foundation of experience and desire. Fascism’s spectacles of death simultaneously spill across reality twice, formalized both as images which prepare the way for further desolation and as desolation which prepares the way for further images. Death never remains content to simply appear but instead relentlessly hungers for its reality, filling screens and in the same gesture filling mass graves.

III

There is no perpetual escape from death, no way of indefinitely negating what for life remains inevitable. The question of living is rather always also a question of dying, just as the degree to which any of us have freedom in our lives is reflected in a freedom to give shape to our deaths. This is true in the existentialist sense that life is always lived in relation to the possibility of taking one’s own life, but also more fundamentally that a truly free life is also a life which is free to give form to the conditions within which their life may end, with whom and how, where and possibly when, even as our lives and deaths can never be entirely foreseen nor planned, bound as they are to the uncertainty of time and the materiality of the Earth. Capitalism’s dispossession of our lives’ autonomy thus must also be understood as a dispossession of our autonomy to have our own relationship with death, to find our own meaning in our end, to die on our own terms.

As the world grows increasingly unlivable, the question remains whether we will be able to constitute ourselves in such a way so that the world is made to be increasingly intolerable.9 A life experiences something as intolerable when it sensually refuses something in the world, when it can no longer withstand an experience and thus is drawn to radically upend the situation within which it lives. An intolerable world is one in which things can no longer simply go on, in which business as usual becomes unbearable and is seen as something which must be overturned. Intolerability explodes in diverse forms, manifesting as workers who walk off the job after a boss has made one too many demands, as students who occupy a campus laboratory when they learn military research is being conducted there, or as prisoners who set fire to the building which cages them after a new round of punishments and restrictions is announced. In each instance, a shifting perspective of the situation also shifts what is possible within it, revealing new lines of flight to follow, new sides to take, new targets to strike. The task of making the world intolerable thus involves a violent break with capital’s sensible organization of the world, just as it involves a sharpening of our senses and a sharing of perceptions which allow us to fully live within and forcefully confront the reality of our situation.10

Fascism’s spectacles create the conditions within which capitalism’s forms of death come to appear as objects that are both detached and desired, and in this way they also function as forms of amnesia and anesthesia, as a forgetting of the history of desolation that is the history of capitalism and as a desensitization of capitalism’s violence which unfolds in front of our eyes. Fascist culture thus works to leave us incapable of making sense of our own lives and deaths by making us capable only of making sense of ourselves as capitalism does. So long as the economy solely determines the way we perceive our lives in the world, so long as wages and not one another are seen as the only means of survival, so long as the market’s future is felt as the only possible future, the economy and its desolation will continue to appear simply as the world. New fissures and fault lines in this situation can be discerned only by assembling and deepening forms of sense which cut through society’s spectacular dimensions, which glimpse forms of life that begin where the economy ends, and thus which break capitalism’s and fascism’s grip on our experience of the world. To make something intolerable is, quite simply, to render its destruction sensible.

While our time is marked by the desolation of life, it has also been shaken by revolts which have emerged as refusals of society’s spectacular violence. The insurrections of the Arab Spring erupted in response to images of the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia and of the state murder of Khaled Saeed in Egypt, and as the police executions of Oscar Grant, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and many others came into view they set off some of the most militant and widespread uprisings in the history of the United States. These revolts were so explosive because they were waged against the whole sensual order of the world, against the way in which society views some lives as worthless, superfluous, and disposable, against a society organized on the basis of ever more unsparing forms of death. The appearance of these revolts in the streets was thus also the appearance of a different form of sense which experienced these deaths not as simply another tolerable sacrifice but as a wild spark to be kindled, built up into a flame, and spread so as to burn ever wider across society as a whole. In the most elementary of terms, a revolt involves rejecting all of the ways life is perceived from the perspective of capital, of the way life is situated within the spectacular order of appearances, just as it involves learning to see the world anew from the ground, on the street among friends, across barricades.

Despite facing dramatic violence and repression, these revolts have continued to break through the surface with a sharp regularity, building upon past fires lit after the murder of Mahsa Amini in Iran, of Alexandros Grigoropoulos in Greece, of Nahel Merzouk in France. The encampments, demonstrations, building takeovers, and acts of sabotage against the ongoing genocide in Palestine also elaborate upon this rich history of those who have rejected society’s desolation of life and embrace of death, who have developed a shared intolerance of society and as a result have gone to war against it. These revolts are dangerous to the extent that they become capable of perceiving the world apart from the sensible order of the capitalist world, and as a result develop their own ways of perceiving one another and perceiving things together, honing a collective capacity to see a multiplication of battlelines cutting across reality where none were apparent before. In a society which allows no perspective but its own, the opening of one’s thought and attention to what is evident all around is tantamount to insurrection.

Confronting what now lays such waste to the world entails taking back one’s own life and death from the society which aspires to organize and determine their value completely, and ultimately taking life and death as the very material of a struggle against capital. It is precisely when life and death are taken back from capitalist society that it becomes possible to develop a sense of what it might entail to risk one’s own life and death in a struggle against death, to give new meaning to life and death by destroying the society which deprives life and death of meaning, freed from the economy as they are sharpened into weapons against it. Grasping life and death in their radical singularity is to grasp them again in their full clarity, to again perceive the full range of what is possible in living and dying beyond and against the logic of accumulation and desolation. The spectacular composition of society can in the end only be defeated by its total decomposition, by a pursuit of meaning and beauty in what brings disorder and destroys value, by an anarchy of form. Capitalism and fascism offer an image of life thinly glossed over a panorama of death. Life must respond by demolishing the whole of the frame within which such an image sits.

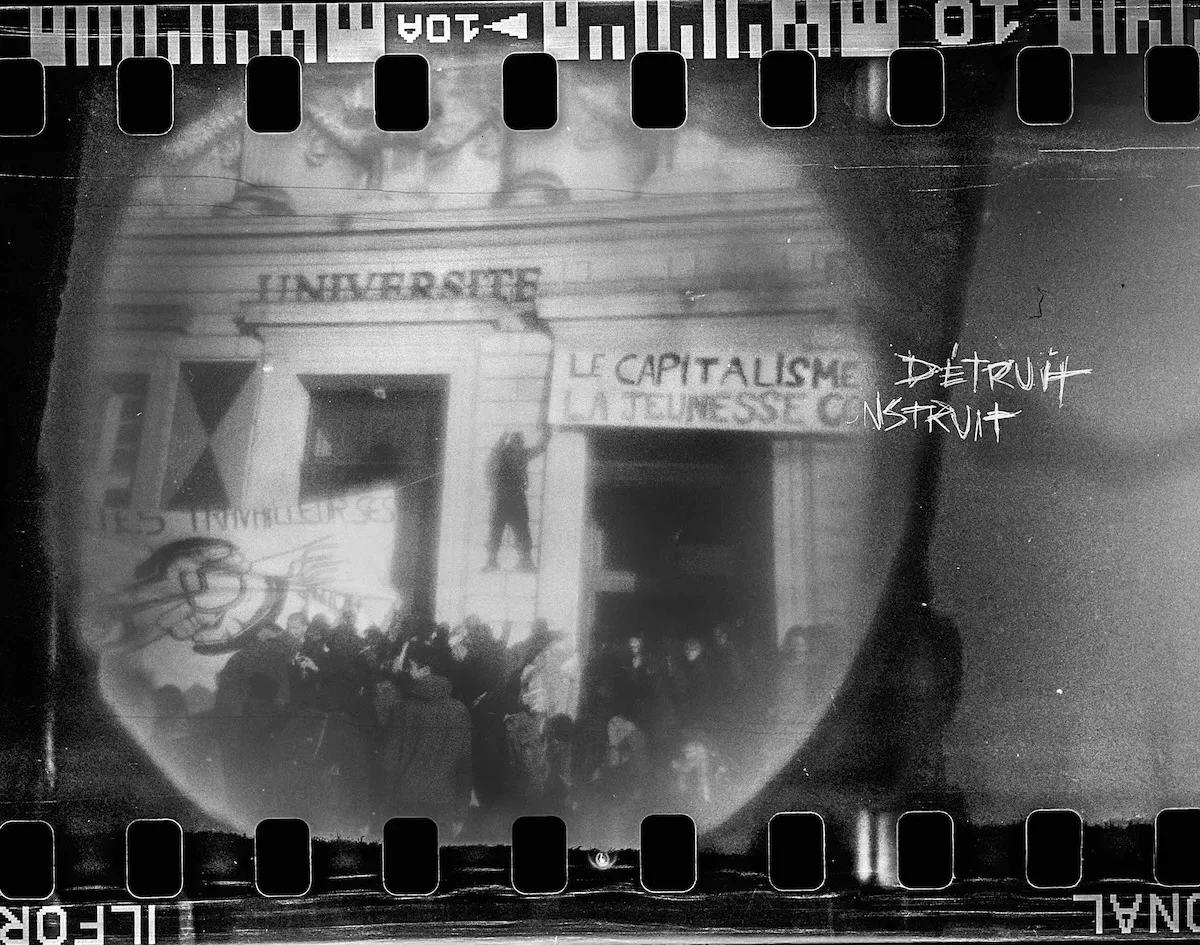

Images: Steven Monteau

Notes

1. “(Mankind’s) self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order. This is the situation of politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic.” Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt, Schocken, 1968, 242.↰

2. The etymology of “Appearance” is instructive here, meaning both to be visible but also to submit (as in to appear before a judge), to be apparent and also to obey. “Apprehend” shares this duality, signifying both to grasp with the senses but also to capture and detain. Encoded in all of this vocabulary is an aesthetic violence, an imaging of the world whose function is to subordinate and dominate it.↰

3. This observation from Georges Duhamel is quoted by Benjamin in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” 238.↰

4. “I call the distribution of the sensible the system of self-evident facts of sense perception that simultaneously discloses the existence of something in common and the delimitations that define the respects parts and positions within it. A distribution of the sensible therefore establishes at one and the same time something common that is shared and exclusive parts. This apportionment of parts and positions is based on a distribution of spaces, times, and forms of activity that determines the manner in which something in common lends itself to participation and in what way various individuals have a part in this distribution.” Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics, Continuum, 2004, 13.↰

5. Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” 242.↰

6. In the final years of the Second World War, the Nazis began experimenting with putting cameras in missiles as part of what the filmmaker Harun Farocki described as war being brought into alignment with the visuality already technologically achieved in the factory, uniting the means of production and the means of destruction in a spectacular order: “Recognizing and tracking objects in the (battle)field is much more difficult than in a factory. A factory is a controlled space, with stable light conditions and a regulated order. The location systems will have to be improved, or, the entire world brought into line with factory conditions.” War at a Distance, directed by Harun Farocki (Video Data Bank, 2003).↰

7. “Increasing the productivity of labor is marked extensively by the introduction of machinery into the production process … While the introduction of machinery holds the possibility of lightening the workload of the workers, machinery also functions to increase the intensity of those still working for capital, without regard for the workers’ health … Simultaneously, the introduction of machinery correlates to a decrease in necessary labor, which corresponds to the number of workers necessary for capital to extract a surplus (profit). Thus, increases in the productivity of labor through the introduction of machinery in large-scale industry increasingly render a large and growing portion of the working population superfluous; humans relegated as the waste necessary for continued capital accumulation.” Michelle Yates, “The Human‐As‐Waste, the Labor Theory of Value and Disposability in Contemporary Capitalism,” Antipode, 43, no. 5 (2011): 1689.↰

8. It is here that the hints of a far more expansive history of fascist aesthetics begin to come into view, composed of the lynching postcards which were widely circulated across the American South and the cowboy westerns which romanticized the eradication of indigenous tribes, of the colonial films shot across Africa and Asia which rationalized and glamorized the violence of capitalist expansion and dispossession, and of course the Nazi films of Leni Riefenstahl and Fritz Hippler which visually paved the way to the gas chambers of Europe. Reflecting on the fascist spectacles produced throughout the 20th century, Susan Sontag astutely observed that they aspired to “give form to reality, itself based on an idea of form.” While elements of Sontag’s critique of fascist aesthetics hold onto much of their force, her refusal to consider the essential ties between fascism and capitalism in the end fatally constrains her project. Only when we grasp that it is the capitalist form of death which fascism aspires to impose upon the totality of social life, that fascist aesthetics function to reorganize life on the basis of capitalism’s desolation, is it possible to truly confront what fascism now brings upon the world. Susan Sontag, Under the Sign of Saturn, Vintage Books, 1981, 85.↰

9. Reflecting on the life of Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze noted that his project involved thinking the intolerable, and thus in becoming able to see what everyone else already knew but nonetheless remained incapable of seeing: “For him, thinking was always an experimental process up until death. In a way, he was a kind of seer. And what he saw was actually intolerable … When you see something and see it very profoundly, what you see is intolerable … For Foucault, to think was to react to the intolerable, the intolerable things one experienced … If thinking did not reach the intolerable, there was no need for thinking … It was intolerable, not because it was unjust, but because no one saw it, because it was imperceptible. But everyone knew it. It was not a secret. Everyone knew about this prison in the prison, but no one saw it. Foucault saw it.” Gilles Deleuze, “Foucault and Prisons,” in Intolerable: Writings from Michel Foucault and the Prisons Information Group (1970- 1980), ed. Kevin Thompson and Perry Zurn, Minnesota, 2021, 386. [An excerpt is available here. —ed.]↰

10. “The big lie is refusing to see certain things that one does see, and refusing to see them just as one sees them. The real lie is all the screens, all the images, all the explanations that are allowed to stand between oneself and the world. It's how we regularly dismiss our own perceptions. So much so that where it's not a question of truth, it won’t be a question of anything … We don’t claim in any instance to convey ‘the truth’ but rather the perception we have of the world, what we care about, what keeps us awake and alive. The common opinion must be rejected: truths are multiple, but untruth is one, because it is universally arrayed against the slightest truth that surfaces.” The Invisible Committee, Now, trans. Robert Hurley, Semiotexte, 2017. Online here. ↰