Fascist Spectacle

Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen

For some years now, Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen has studied the new forms of emergent fascism in our day, first in his Trump's Counter-Revolution (2018) and most recently in Late Capitalist Fascism, out this November with Polity Press. In this new essay, he positions the rise of neofascism against the backdrop of an imploded class politics in order to ask whether fascism today resides in a kind of sickness hidden in the "folds" of the neoliberal psyche?

Other languages: Français

The return of violent identitarian emotions fueled by nationalism, racism and religious fanaticism prompts us to pose the question of fascism as something more than just identifiable enemies we can combat. Is fascism a kind of sickness, hidden in the folds of our psyche, inside our impoverished “neoliberal” subjectivity? The absence of fascist mass parties, the BJP being the prime exception, should not lead us to believe that fascism has not returned. It clearly has, but in a strangely evaporated form with mediocre pop fascist leaders, spread out on social media, and even more contradictory and backward looking than its 1930s versions.

After forty years of neoliberal global capitalism, the market and individual initiative rule supreme but, confronted with escalating conflicts and a never-ending crisis, need a strong state capable of repressing the racialized elements of the dangerous classes, migrants, Muslims, Mexicans, Jews, etc. The COVID-19 pandemic is only further aggravating things, damaging the economy and rendering more people unemployed. Fascism emerges in order to prevent a real shift in perspective, where people turn away from ‘stabilized animal society’ — that is, from those apparatuses and ways of life that mould our species into an animal that can reproduce only through wage labour and capital — and it does so by mobilizing the social forces of a fragmented mass society through aggressive nationalism.1

For the last forty or fifty years we have witnessed a prolonged economic crisis. For a long period, this crisis was masked under enormous amounts of credit and the local modernization of SouthEast Asia. But in 2007–8 the crisis became visible for everybody to see, and since then it has been the “new normal.” What started as a financial crisis, but was in fact a longer economic crisis, quickly became both a political and social crisis as governments were unable to readjust their policies and simply continued with more of the same — that is, an unstable mix of printing money (to the banks) and implementing austerity. The result has been a further hollowing out of a national democratic system that seems to primarily benefit the interests of business and a small elite. Meanwhile, the last ten years have been characterized by the return of a global discontinuous protest movement and the tremendous surge of racist agendas and fascist politicians that have proven capable of breathing new life into electoral procedures. The new fascist leaders have stepped in and are now upholding the national democratic systems they ostensibly are there to protest. Fascism is a protest, a protest against the long slow neoliberal dismantling of the post-Second World War social state, or a certain idea of the world of that time. The fascist leaders conjure an image of that time, a better time, before unemployment, globalization and the emergence of new political subjects threatening the naturalness of the patriarchal order. Migrants, people of colour, Muslims, Jews, women, sexual minorities and communists are perceived as the causes of an historical and moral decline that the fascist leaders promise to reverse engineer by excluding such unwanted subjects and restoring the ‘original’ community.

But fascism is also a protest against the protests: as George Jackson explained in Blood in My Eye, fascism is a preventive cancellation of the possibility of the emergence of more radical opposition against neoliberal globalization and the capitalism–nation state nexus.2 Fascism blocks the genuine anti-capitalist front, which we can already see in embryonic form in the many protests, riots, multitudes and assemblies that keep taking place in a stop-and-go pattern across the planet.

From Wilhelm Reich and Deleuze and Guattari, we know that fascism is not just a matter of political leaders and parties, but also a matter of micro-politics and desire.3 The masses desire fascism. People have not been duped into supporting Trump, Le Pen and Salvini or voting Britain out of the EU. Fascism is a micropolitical phenomenon and is present everywhere, not just at state level. Fascism is present in the family, at the office, in the countryside, and in the city. It is present before it manifests itself as what we normally speak of as fascism. Fascism “is inseparable from a proliferation of molecular focuses in interaction, which skip from point to point, before beginning to resonate together in the National Socialist State.”4

With Reich and Deleuze and Guattari, we can see fascism as a pre-existing phenomenon — visible, for instance, in the way in which Native Americans and African Americans are treated in the USA, from settler colonialism and slavery to police shootings to mass incarceration — that is then transformed into a (macro)political project through various fascist formations. Fascist violence against women, African Americans, and minorities is now a political program as such, and no longer merely exercised in the “private sphere” or as the slow structural violence of capitalist reproduction. White domination is now a political project. The political violence of fascism is being organized, and the liberation from self-restraint and the enjoyment of the violent exclusion of the other is now recognized as a political goal in itself.

The fascist potential never really went away. George Jackson and a long list of Black revolutionaries stressed this point all along, even during the heydays of ‘the social compromise’ of the Post-War era. For a while it did not take the form of state formations or political parties capable of competing for power, but it was there all along. It was just a matter of perspective. And where one looked.

All Identities

Much has been written about the new fascists’ ability to appeal to the white working class. Trump, Salvini and Meloni, Le Pen, Farage and Bolsonaro, and earlier Pia Kjærsgaard of the Danish People’s Party, have all been able to absorb a large chunk of working class votes in elections. This development is of course related to the large center-left parties administering neoliberal policies, privatizing, cutting welfare and upwardly redistributing. But it is also related to the disappearance of the working class as a caste-like political form and lived relation embodied in organizations, parties and cultural institutions. As G.M. Tamás has argued, from the mid 19th century to the late 1960s, the working-class was a distinctive culture that fought against the old order and wrestled with the bourgeoisie over the right to run the capitalist economy.5 The organized working-class movement in Europe seldom strove for the abolition of the money economy and the nation state, struggling instead to improve the lives of workers and build up a large institutional infrastructure from where it could pressure the capitalist state into better working conditions and political rights. In the developed (or rather, over-developed) world this led to the creation of the post-war social state where capital and labor “found” each other in soaring productivity rates. Adorno called this the classless class society. The amelioration of the everyday life of many workers resulted in the abandonment of a push to radically transform society and end capitalist domination. Older class structures were reconfigured and even seemed to disappear, as large parts of the working class moved upward into the middle class. As Jacques Ellul once remarked, the middle class became the invisible class in this period, the class that both integrated parts of the working class and leveled itself out, concealed itself as a class, and simply became modern society.6 This is the story of the emergence of a set of forms that universalized class power, made it invisible. Everyone in the overdeveloped world was middle class. Or so it seemed. Even migrant workers were welcome, although, of course, still subject to everyday racism. Individual freedoms replaced class struggle in this process. Revolutionary energy was frozen.

May ’68 was a social explosion that partly reintroduced a revolutionary perspective, shattering the dream of a Keynesian classless society. But the revolution never happened; May ’68 was an expanded revolt fusing insurrection, revolt, and reforms where young people, women, and migrants rejected the Fordist wage productivity compromise and the democratic welfare state. The rejection took the form of an extended expansion of consciousness lasting several years. It was a partial rediscovery of the revolutionary proletarian offensive from 1917 to 1921, but without the emergence of any revolutionary project for the creation of a communist society without money or state. The May revolt never got that far. It was more a series of partly overlapping experiments wherein predominantly young people lived differently, rejecting work and consumption and thereby refusing the foundation of the compromise between the capitalist state and the organizations representing the workers (in the West).

The refusal of the new consumer life, but also the old pretentious leaders – de Gaulle, Adenauer, Waldeck Rochet – who had brokered the Fordist compromise, paradoxically gave way to a new strategy of capitalist exploitation. The revolt was crushed but also repurposed, its “social” dimension wrested from its political content and put to use in a new accumulation regime. Authenticity became a neoliberalist catchphrase. The demand for a different life was turned into the desperate search for individual satisfaction and quick identity fixes. The experiments of the long ’68 morphed into a hedonistic lifestyle culture, and politics dissolved into business and the stock market.

The period from 1968 to 1974 was marked by a transition from a modern to a “postmodern” form of critique in which an older oppositional culture, embedded in the labor movement and its ideology of labor and progress, was criticized and expanded with new non-class-based protest cultures focusing on social roles and the relation to nature. This expansion, or “break in the theory of revolution,” as Théorie Communist have dubbed it, quickly led to an epochal weakening, however, in which the idea of a different life was internalized into what Giorgio Cesarano called “the revolution of capitalism” in the beginning of the 1970s, where former cultures disappeared and were replaced by a new conformism based on easy access to commodities.7 Cesarano understood this as the installation of a new regime of power that operated from inside the subject. The wish to consume is a longing to obey an order that has never in fact been given. This new power dissolved the remaining collectivity associated with working class culture, paving the way for a new individual lifestyle of consumption. Today, people are only together in so far as they are separate. The idea of a different community might have briefly resurfaced in May ’68 but it promptly disappeared, and today we are left with “repressive tolerance,” that is, entities like the nation state, the family, private property or the individual with its “free” sex life.

The working class disappeared. But class struggle did not. For 40 years the ruling class has been busy amassing more and more wealth from a system that is producing less and less profit. The strength of the labor movement was dependent on labor productivity gains being shared between labor and capital. But the period since the early 1970s has been characterized by the dogged refusal by the capitalist class of wage sharing in a context where productivity gains have tapered off. The result is chaos: more and more people excluded from wage labor, struggling to get by and controlled by the police. This is the world of late capitalism. And fascism promises to confer an advantage on the “true” constituency of the nation, the people. To white Americans, the real French, the true Italians and ethnic Danes, those who are Muslims, migrants and descendants of immigrants have to go, move elsewhere, disappear. They are not part of the people. There are less resources to go around, but you will get privileged access to what’s left after the ruling class has taken its share. That’s the bogus promise of late capitalist fascism.

In this situation any attempt to recompose the working-class is parodic. It is somehow easier to conjure an idea of a lost national community. Not least because it is easier to personify a dangerous and “parasitic” enemy that is threatening your welfare and the completeness of the national community, be it Muslims, Mexicans, Jews or Marxists, parasites alike. Visualization of the impersonal laws of capital accumulation is no match for fascist pseudo-concretion: here’s your enemy; look at their dark skin, strange clothes or weird cultural habits. Trump, Salvini, Orbán, Thulesen Dahl and Bolsonaro are all “fabricating a people” by targeting Blacks and Mexicans, the Roma minority, Muslim immigrants or Amazon Indians.

The emptiness of late capitalist society is hidden in plain sight. The working class has disappeared. Today, the term “worker” is invoked as a political identity to channel hatred towards foreigners. Class struggle has become bad identity politics and the old political dichotomy of left and right has finally revealed itself to be devoid of meaning, a holding pattern for the political spectacle of the old national democracies. Constant replacements and manipulations are the order of the day. Politics has been business for so long that the only possible opposition is reviving grotesque fascist characters that might present themselves as alternatives, but in fact only confirm the hollowness of democratic institutions and indefinitely postpone a negation of the money economy and the nation state. Religious superstition and new-old forms of nationalism run rampant all over the place, not only in the beleaguered hegemon of the US. More or less everywhere, the instant satisfaction of Facetune goes hand in hand with ever more empty references to lost communities. The Spectacle 2.0 is the ideal setting for nostalgic and increasingly violent re-enchantments of dreamt-up social relations.

The worker disappeared, abandoned by the left and center-left parties, duped by the prospect of a steady job and credit to buy cheap commodities and gadgets. The dream of a world where each new generation (in the West) would get more was never going to come true. Only for the select few was that the case anyway. Capitalist destruction and unevenness were somehow transformed into underdevelopment and temporal decay. But now unevenness has begun to reappear, and is no longer reserved to the former colonies or the backyards of the metropoles of the old center. It has become something of a nightmare even for the children of the lucky ones who were compensated. “Poorer than their parents” was the title of a notorious 2016 report by McKinsey Global Institute. For the first time since the 1950s, it asserted, young people in the West can look forward to a life where they are worse off than their parents.8

Today, everything is identity, including class. To rewrite Stuart Hall, we can say that identity is the modality through which class is lived. Intersectionality stands as the cipher of this conundrum, an inability to theoretically and politically deal with and overcome this (unity-in-) separation. The proletariat is fragmented, split up and unable to form a movement. Class composition is decomposition today. And it is very difficult to mobilize the disgruntled mass as anything other than a racist mob.

Take the Yellow Vests in France. A composite movement if there ever was one. It started out as a protest against a fuel tax, with people occupying roundabouts all over France. It emerged from online discussion forums entirely external to trade unions and left-wing organizations. Their symbol was not the red flag but a yellow vest, an object all French drivers are required to possess in their cars. The vest made them visible in a world where they are condemned to invisibility and social suffering. A world where lower middle class families in rural France have to choose between the price of petrol needed to drive to the supermarket and the food they could buy there. The movement was ostensibly against Macron and the financial elite he represents, but the refusal it expressed was not channeled into any kind of political representation. That was not possible. People were simply against, and did not want to give up on their petrol-based life. It was a reaction. The movement both mobilized people who were losing their former way of life, and people who wanted something different. But there were no real demands or attempts to pose any kind of vision. What was most telling was the contradictory character of the movement, in which protesters waved French flags while desecrating the Arc de Triomphe, one of the most sacred symbols of the nation. My point here is that we are living in a highly unstable time where it is difficult to make the leap from identificatory claims to a revolutionary perspective. The Yellow Vests and all the other protest movements are searching for strategies but have so far proven unable to produce any, and can therefore only disrupt the status quo. To refuse the present (dis)order is the order of the day. It was the same with the George Floyd protests, which proposed very little but simply attacked the state through the police.

The lesson of the ongoing anti-state protests is thus paradoxically the same one that late capitalist fascism is teaching all of us: all political conflicts have been transposed into identificatory terms. We are confronted with an objective disorder that gets expressed subjectively through different kinds of refusals, including fascism’s gesturing to a near past, protests that all run up against a real limit. The eroding (wages of) whiteness will not be restored to their former glory by border walls, Muslim bans, reindustrialization, or scapegoating racialized enemies. But of course, it might stave off a real challenge for a while. That’s the function of fascism.

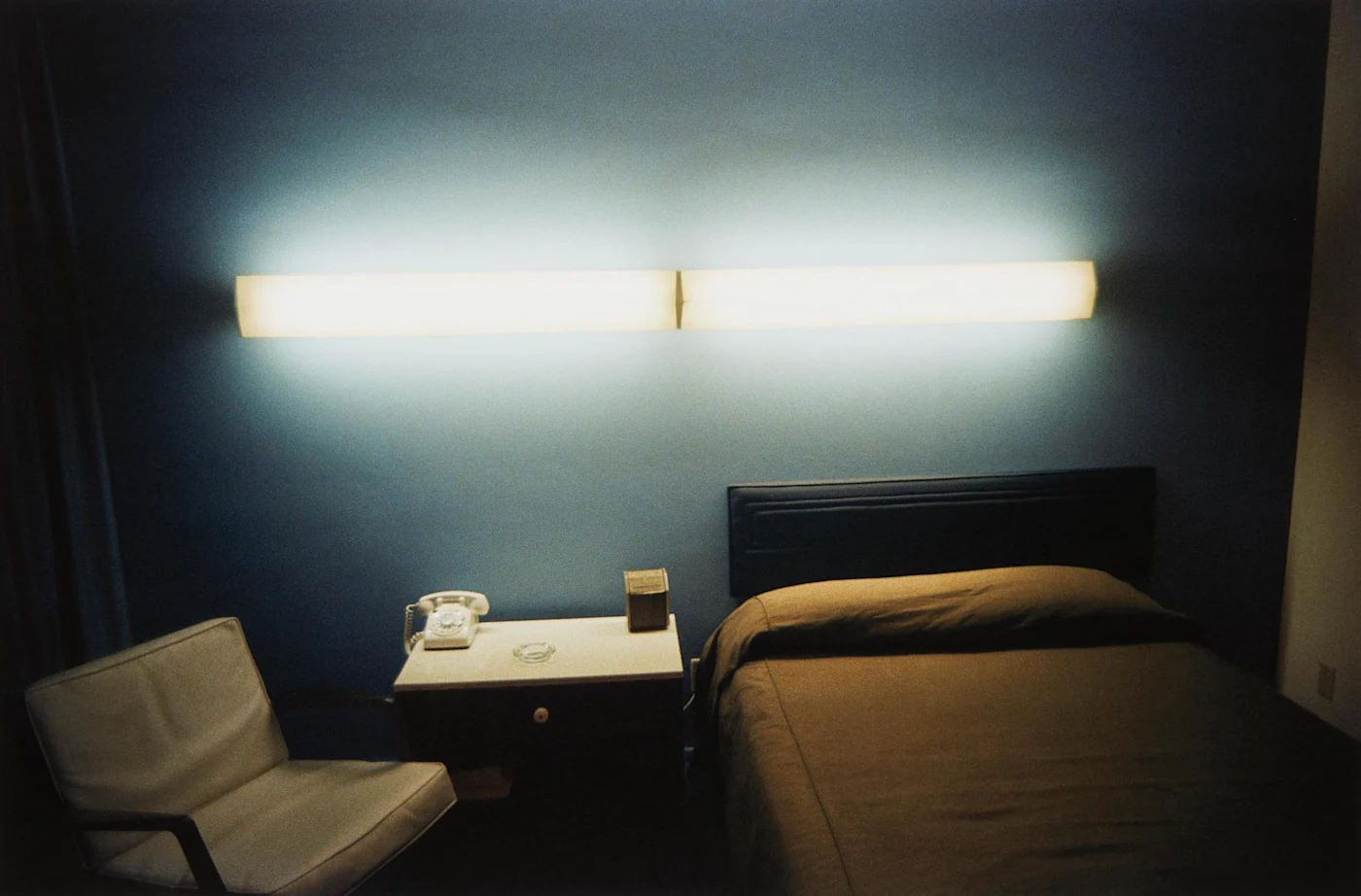

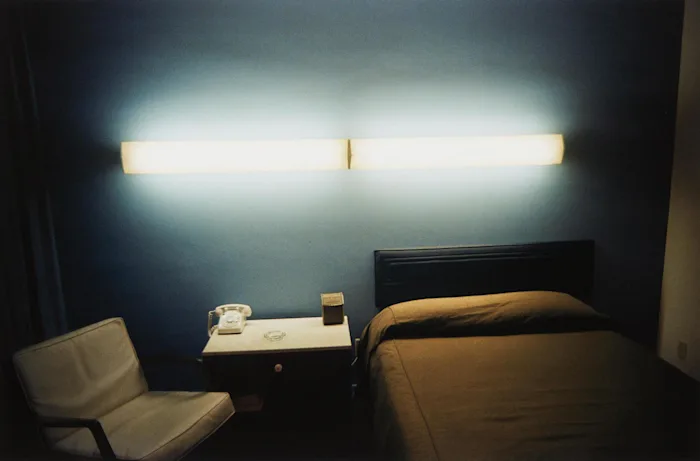

Images: William Eggleston

Notes

1. The notion of ‘stabilized animal society’ is developed by Giorgio Cesarano: Manuale di sopravvivenza, Dedalo, 1974, 66. And later put to use by Tiqqun: The Cybernetic Hypothesis, Semiotext(e), 2020, 48.↰

2. As Jackson puts it: “The ultimate aim of fascism is the complete destruction of all revolutionary consciousness.” George Jackson: Blood in My Eye, Random House, 1972, 137.↰

3. Wilhelm Reich: The Mass Psychology of Fascism, Orgone Institute Press, 1946; Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari: A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia, University of Minnesota Press, 1987.↰

4. Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari: A Thousand Plateaus, 214.↰

5. G.M. Tamás: “Telling the Truth about Class”. Leo Panitch & Colin Leys (eds.): Socialist Register 2006: Telling the Truth, Merlin Press, 2005.↰

6. Jacques Ellul: Métamorphose du bourgeois, Calmann-Lévy, 1967.↰

7. François Danel: Rupture dans la théorie de la révolution. Textes 1965-1976, Senonevero, 2008; Giorgio Cesarano & Gianni Collu: Apocalisse e rivoluzione, Dedalo, 1973.↰

8. McKinsey Global Institute: Poorer than Their Parents? Flat or Falling Incomes in Advanced Economies. 2016; online here. ↰