Charles Fourier, or the Great Swerve

René Schérer

A century and a half before Norbert Wiener established it as the science of order, Fourier discovered the antidote to the cybernetic worldview that constitutes the spontaneous ideology of late capitalist life. In his 1967 preface to Charles Fourier, l’attraction passionnée, translated here for the first time, René Schérer (1922–2023) argues that the enduring urgency of Fourier’s work lies not in his specific proposals for collective life, often laden with bombastically fantastic detail, but in his methodology. By radicalizing the procedure of Cartesian doubt and redirecting it against the very foundations of civilization itself, Fourier liberates doubt from the Cartesian certainty of “man as an indivisible source of values.” Rousseau challenged civilization only to rediscover a “natural” moral man, while Marx questioned the capitalist order without challenging the anthropology on which it rests; but it is only Fourier who manages to dislodge the entire classical image of the self as such. By conceiving social, animal, organic, and material relations as an ordered whole, Fourier denies human existence its place at the center of life’s forms. Once everything is in correspondence with everything, the world is decentered: the human “is entirely outside himself, defined by his relations with his environment, by the place that he occupies at any given moment,” able to rediscover himself only from the point of view of totality. It could perhaps be said that the entire post-human turn in anthropology, from Bruno Latour and Anna Tsing to Donna Haraway, owes a debt to Fourier. Yet with the difference that, while the latter theorists remain hampered by the melancholia of “surviving among ruins,” Fourier refuses to submit to the Hegelian dialectic of transgression and loss, with its tragic miserabilism. Whereas dialectical champions of desire accept dissatisfaction as the price of doing business, Fourier strips away the secret resources on which the metaphysics of lack and transgression, sin and repression depends: “the absence of the sacred on which sacrilege feeds. Nowhere is God more absent.” Passion for Fourier is not “a violence that divides, a communication rendered impossible, but on the contrary that which connects.”

A similar radicality surrounds Fourier’s conception of labor. By contrast with the lionization of labor in Marxism, which, even released from relations of alienation, continues to identify labor with “effort and civic duty,” in Fourier labor is subordinated not to the law of value but to the laws of attraction. Once it is released from the competitive, professional ceremonies and rituals of the market, such activity loses its afflictive character and becomes the impetus for new collective assemblages of desire. In this way, Fourier anticipates the conversion or metanoia whereby the world becomes an object of attachment precisely through its construction as a site of collective defense.

A friend and colleague of Deleuze, Foucault, Rancière, and Guattari, Schérer helped found the Revolutionary Homosexual Front [FHAR] alongside his lover, Guy Hocquenghem. A major anarchist philosopher in his own right, author of 20 books and co-editor of the journal Chimères, Schérer died in February 2023, a few months after his 100th birthday.

Life is a long torment for those who serve unattractive functions. —Fourier, The Universal Unity

To the great scandal of some, under the scarcely less reproving eyes of others, raising its weight of wings, your liberty. —Breton, Ode to Charles Fourier1

We no longer read Fourier. Our epoch, smitten by seriousness, has no use for him. Seriousness is politics viewed as strategy, economics based on profitability. It is also the institutions that immutably traverse all regimes: religion, the critique of which, as we know, is at best outdated, at worst a compromise; the State, which gathers strength even through our talk of dissolving it; the family: cleansed of all suspicion it gently enters into immortality. Seriousness is the existing society, considered as the only rational one because it is the only real one, and the historical understanding of this society, that is, everything that works to justify it.

In the light of this wisdom of nations, Fourier's reveries appear unrealistic and comical. The phalanstery is a museum piece, a curiosity for historians. As for Fourier's analysis of the economy, it is so rudimentary and retrograde that it does not even merit discussion. Fourier envisages a basic association that is essentially agricultural (or rather horticultural) at a time when France is industrializing; he is blind to the economic dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, even if he denounces some of its effects, and has no idea of the law of profit and the reproduction of capital; in fact he would preserve it in a society where the instruments of production will apparently be collectively owned. Above all, however, he neglects to define the rational and historical paths to the radical change he envisions: this thinker with revolutionary pretensions abhors revolution and expects the implementation of his theories to come about through the goodwill of individuals, or even a prince. The study of the historical conditions of possibility, the ABC of any action, does not concern him for a moment. How much more lucid is Stendhal who, although an admirer of Fourier, writes:

Fourier, living in solitude or, what is the same thing, with disciples who dared not raise objections (moreover, he never responded to objections), did not see that in each village an active and smooth-talking scoundrel, a Robert Macaire, would place himself at the head of the Association and pervert all its beautiful consequences.

In short, Fourier's work does not fall into any of the political, economic, or psychological categories of modern consciousness; today's world refuses to accept it. It does not define a practice, since it abstracts from the action that can be carried out in given circumstances; nor is it a theory in the strict sense of the word, that is, a scientific study of real life.

When Fourier is classed among the utopians, it seems that everything has been said; he is given a place that allows him to be ignored; he is relegated to the prehistory of socialism, which only begins with scientific socialism, that is, with the discovery of the laws of class struggle and capitalist production.

Not that the founders of this socialism themselves despised Fourier. Engels paid him the highest tribute, which is worth reflecting on to convince ourselves that seriousness is not always where we think it is:

Let us not dwell on this fanciful side, which belongs entirely to the past. Let literary pedants solemnly dissect these phantasmagorias, which today make us smile; let them assert the superiority of their cold reason at the expense of these utopian dreams; for our part, we take pleasure in seeking out the seeds of genius hidden inside this phantasmagorical envelope, for which these philistines have no eyes.

But this praise also serves as a eulogy. The method is not difficult to recognize: it consists in eliminating all that is inconvenient in order to preserve only what resembles oneself; the pedagogy of the kernel and its shell. It is expressly and exclusively insofar as Engels sees in him a precursor of Marx that he discovers and recognizes in Fourier a “rational core”: insofar as Fourier was a Marxist avant la lettre, by highlighting social contradictions and certain aspects of alienation in the mercantile system. In Fourier’s “core,” Engels even goes so far as to discover a kinship with his contemporary, the philosopher Hegel, a kinship that is certainly tenuous, since it resides essentially in the division of the history of society into stages, from savagery to civilization. Such a comparison crushes its subject; the praise is a bit excessive, exhibiting a misunderstanding. There is a way of absorbing Fourier which is an easy way of getting rid of him.

But, Fourier, irritating and lacking seriousness, resists; and he resists Marxist understanding as well as bourgeois irony. He does not merely prefigure Marx, he is in no way a socialist, he is certainly not a Hegelian. How, then, can we grasp him if we cannot classify him?

The surrealists are undoubtedly the only ones who took him as he was, with his fantasies and his delirium, his meticulous attention to detail in organization, his rejection of importance, which upsets the order of important things. Breton said the essential about him in his Ode: only, speaking as a poet, he suggested it rather than defining it. The language of the Ode erects a splendid statue, but it is not an explanation. Surrealism is content to discover in Fourier a visionary, but it neglects to provide us with paths towards reading him.

However, we cannot read Fourier until we know what we can reasonably expect from him, what we can ask of him. The following few indications are intended solely to try to delimit this request.

Fourier practiced a method inspired by Descartes, which he sets out in The Theory of the Four Movements. He calls it Absolute Doubt, or the Great Swerve [L'Écart absolu]. This doubt is applied to a specific object: society, and particularly the stage of society in which we live, civilization: “We must therefore apply doubt to Civilization, doubt its necessity, its excellence, and its permanence.” However, to doubt civilization means not merely criticizing certain aspects of it, seeking to improve it, or even to revolutionarily change its power structure, but to undermine it in its very principle. Of course, Rousseau had already challenged civilized man, but he did so in order to rediscover in natural man the moral virtues engendered by nothing other than civilization: are innocence and purity of morals anything other than the most refined representation of the civilized? Marx doubts the capitalist order, he even challenges it in its entirety. But it is not civilization that he attacks, only the perversion of values in bourgeois society. In this sense, Marx remains more deeply attached than might appear to be the case to the ideas and values of classical philosophy, to a civilized conception of man: he turned the theories on their head but did not assert their nullity. In Marxism, the moral man, heir and product of a culture, continues to reign supreme. Fourier rejects all this: both culture, understood in the sense of the progressive formation of man though history, and morality. He is left with nothing, not even man as the indivisible source of values. For, as a first and paradoxical consequence, Cartesian doubt, applied to civilization, turns against Cartesian certainty, the purest expression of the civilized soul. Absolute doubt about civilization begins with the undermining of the classical image of the self.

The Theory of the Four Movements, with its parallelism between social movement, animal movement, organic movement, and material movement, effectively decenters the world: by allowing it to be thought of as an ordered whole, there is no longer any recognizable center. Everything is connected to everything else; man can only understand himself if he learns to rediscover himself from the perspective of totality, one name for which is God and another nature.

But let us be clear, this God is not the God of revelation or of morality, and this nature is not a state opposed to civilization, as a so-called natural society opposed to an evolved society. The first society, savagery, is not yet in accordance with nature. Man lives there in ignorance of himself and of the harmonic order. To find man, beyond the representation of himself that all societies have provided him with, is first to divide him, in order to bring him back to the unity that he lacks. In Fourier there is a constant oscillation between division and unity. This is because unity is always both underlying and absent. There can be no understanding of what man is unless we replace what philosophers have called “the subject,” which then loses its intangible identity, with something else: namely those tensions or attractive movements which, in the order of totality, constitute his reference points and assign him his Conjunctions [Jonctions]. Man is no longer within himself. He is entirely outside himself, defined by his relations with his environment, by the place that he occupies at any given moment.

But he is not empty; he is not a mere absence, nor the mere meeting point of forces outside himself. Through the movements that define him, he reaches out towards things and others. Fourier calls these movements, which are relational in essence, passions.

Fourier's entire theory can be understood by reference to passionate attraction, which unites what is most intimate in sentient man and what is most mechanical in material movement. Everything is passion in the same sense that everything is attraction. Nature explains man, who in turn explains nature, which in turn leads back to him. In this perpetual decentering, circularity is the only center.

It is therefore not a question of changing man; it is a matter, rather, of changing everything in the idea of his being and his unity. And all this can only be changed if we rely on primary passionate movements, which are indestructible insofar as they are less the expression of internal forces than the register of all possible relationships.

Since we are more accustomed to reading Nietzsche than Fourier, we can approach Fourier by recognizing that Nietzsche's proposition is already at work in it: man must be overcome. Fourier gives this proposition an acceptable meaning: I mean acceptable for those who do not believe that he must be overcome in the equivocation of the “overman.” We can overcome the image of the enslaved and unhappy man only by changing nothing of what makes him, through the multiple relationships he maintains, the constituent element of a unity.

In what amounts to the same thing, we could as easily approach Fourier by reversing that moral doctrine of Descartes so endlessly drummed into our ears: better to change my desires than the order of the world. For desires, that is to say passions, are precisely what cannot be changed: in them lies the key to order. As for the order of the world, that of civilization, it is this that must be changed from top to bottom in the very name of desire.

However, an important reservation must be made on this last point, which once again sheds light on Fourier’s deviation from our habitual ways of thinking.

Passion, for Fourier, is not identical with desire; it even excludes it in its total exercise. The object of desire, as we understand it, is always elusive; desire feeds on its dissatisfaction. Passion, on the other hand, always finds its object and is satisfied by it, if only temporarily. The only passion listed by Fourier that resembles desire would be the “butterfly,” which flits from object to object. But it only resembles desire, it does not have the same structure.

However, such a difference is of major importance. In the suspicion directed at Fourier by serious thought, I see mistrust of a man who had the audacity to ignore the depth of dissatisfaction, who so radically missed the tragedy of existence. The important thing, we’re told, is tragedy; Fourier, as untragically as possible, thinks of Harmony, a naive and discredited notion. He does not see in passion a violence that divides, a communication rendered impossible, but on the contrary that which connects: “The question arises as to whether passions are made to isolate human beings or to rally them together and establish links between them” (Parcours de l'Unitéisme). This thought is enough to irritate even those among our philosophers who have learned to move beyond the idea of a morality in which law takes precedence over desire. We do not see in it that depth where desire resounds. We agree to let desire prevail, on the condition that we are satisfied with its dissatisfaction.

But what if the dissatisfaction of desire were merely the last bastion of a thought born of civilization, which opposes it only by remaining within it? Fourier's absolute divide therefore involves challenging the last piece of evidence that we assumed to be indestructible, since it did not stem from a confidence in convention but from rebellious, authentically philosophical thinking. Remove the tragedy of the human condition, and no metaphysics is possible. The negation of metaphysics accompanies the doubt applied to civilization. Which so-called profound author has dared to go that far?

I’d like to draw another parallel: in the numerous critical texts that Fourier devotes to morality, there is an astonishing kinship with Sade.2 Now, we take Sade very seriously, whereas Fourier makes us smile. I see the reason for this in the fact that, in Sade, desire is only ever satisfied through transgression: the law forms the indispensable backdrop of the virulence of passion. Sade undoubtedly overturns all moral conventions far more violently than Fourier does. Fourier is timid and petty-bourgeois compared to the aristocratic Sade. We are even surprised that he did not dare to eliminate certain apparently superficial passions from Harmony: for example paternalism, familism; that he almost ignored the fact that perversion was also part of the natural order, that he failed to recognize childhood sexuality, and basically spoke, frightened by his own audacity, very conventionally of love.

However, the fact that he did not use his language to the full, hampered by who knows what reticence, is not so important. The essential point, which allows us to see in Fourier a more radical contestation than that of Sade, lies elsewhere. I detect it in an absence: the very absence of the idea of transgression within passionate satisfaction. The absence of the sacred, which feeds sacrilege but is of no use to those who have definitively expelled it from its lairs, is not only hidden, but barred.

Nowhere is God more absent than in Fourier. This might seem like a paradoxical assertion at first glance, given that Harmony is nothing but the realization of divine designs, and a large place is reserved in the societal order for the cult of divinity.

But God is absent in the form of the repressive power that civilization has given him: that of the God of the Law, the source of all guilt, the creator of sin. Fourier's universe is without sin, without repression. It is empty, even though the idea of paternal love is maintained, of the presence of the father and mother. The man stands in a direct relationship with the woman and the child, but the family knot, where the religious spirit latches on and never lets go of soul, has been severed. Eugénie's sacrilegious jubilation in the presence of Mme de Mistival would no longer be possible in Harmony, where it would satisfy no passion. It would have no meaning there.

With Sade, everything must be sacrilegious, whereas with Fourier nothing is. Let us grant Fourier a more precise understanding of the springs of passion3, let us free him from the restrictions imposed upon him by his family background, his culture, and his audience, and Harmony becomes the very implementation of this lawless society (or one with as few laws as possible) which Sade only sketched out in negative terms, since he ultimately did so within the framework of a civilization whose presuppositions he accepted as indispensable to his passionate contradiction. But what passion or pleasure principle would take the transgression as its end if the restrictive power of the law were lacking from the outset?

We should be clear about this lack: law is missing, but not structure, that is to say, order. It is no easy task to rid order of law, especially when it comes to understanding how passion fits into order, how each person can achieve satisfaction by receiving his or her summons from a structure. But the mere mention of these relationships is enough to show that, according to this other approach, Fourier is less alien to us, that he anticipates the findings of the most precise contemporary research seeking to formalize that most elusive aspect of life, namely, experience. However, we still have not situated Fourier’s theoretical articulations, which are far from explicit. Fourier legitimizes less than he presents; his reasoning is difficult to follow from beginning to end. Here again, his excessively absolute departure from scientific or demonstrative logic requires us to begin searching for the articulation of his discourse in its flaws or differences.

I’m looking for a point of reference, and I find it in Hegel, since he stands at the horizon of modern thought. The comparison is illuminating: not, as I’ve already said, because Engels believes Fourier handled dialectics as well as Hegel did, but on the contrary, because he proposes a type of rationality that is the inverse of Hegelian rationality. To be sure, both think in terms of totality: the true is the whole. But there are two different ways of conceiving totality: either dialectically, as Hegel does, or, as Fourier does, according to a method whose principle must be recognized.

Hegelian dialectics, and the methods inspired by it, inscribe the whole of reality in a discourse that is essentially unitary (philosophical or scientific) and continuous, in which each element, or “moment,” denied in its independence, is preserved in a modified form, thanks to its belonging to the whole. The form of the dialectic is time, for it is through time that everything is erased and, at the same time, maintained. The temporal structure can, moreover, be spread out in a simultaneity, when it is a question of understanding a present totality; dialectical integration nonetheless obeys the same law.

Take the family, for example: for Hegel, it is not the completed form of society, but an essential “moment” of law and mortal consciousness.

On the other hand, the inner driving process (and no longer the formal structure) of the Hegelian dialectic coincides with the gradual interiorization of what at first exists only in the exteriority of the institution, or the passage from what Hegel calls “substantiality” to “self-consciousness”: we understand once again why, by virtue of this driving force, it requires a progressive and unfailing discourse.

Let us return to the previous example: the family, the substantial milieu of moral conscience, has the dialectical function of bringing the individual (consciousness) from spontaneous, externalized, or objective morality to personal legal existence, to self-consciousness. Designated for this purpose, it can therefore only be monogamous: “Marriage is essentially monogamy, because it is personality or immediate exclusive individuality [Einzelheit] which enters into and surrenders itself to this relationship” (Elements of the Philosophy of Right, § 167). Or again: “Marriage, and essentially monogamy, is one of the absolute principles on which the ethical life of a community is based.”

There can obviously be no question of “free” love, since it would contradict the personal existence to which the dialectic assigns an exclusive place in marriage. As an “element of natural life” it is, in any case, overcome [dépassé] in the substance of marriage as an “immediate moral fact.” On this moral basis, a dialectical overcoming of marriage does indeed take place, but forwards and not backwards, once the individual, formed by the family, becomes a citizen, a legal being. Having reached this point in dialectical development, how would the idea of eloping elsewhere even arrive to him?

Now, let's see how that other pillar of social existence, labor, is understood by the Hegelian dialectic. It too is a mediation between nature and the highest forms of law. To be sure, Hegel perceived quite clearly the contradictions between increasing wealth and impoverishment: “The tendency of the social condition towards…luxury…has no limits, [and] involves an equally infinite increase in dependence and want” (§ 195). This quote can be compared to Fourier’s remark that, “poverty in civilization is born of abundance itself.” But what does Hegel make of this observation? He does nothing with it; or rather, he strips it of its virulence by integrating it into his dialectical discourse. The dialectical essence of labor takes precedence over this contradiction and covers it up: “By a dialectical movement, the particular is mediated by the universal so that each individual, in earning, producing, and enjoying on his own account, thereby earns and produces for the enjoyment of others” (§ 199). Now, this is not a picture of another society, but a dialectical understanding of the very society that was previously said to engender misery. What is important for philosophical discourse is not real poverty and wealth, but the possibility of exposing what immediate consciousness proposes as an end as merely a moment or mediation. The system of needs is overcome in the higher moment of the legal state, which retains only the universal form of the result: property. You have nothing, but work for everyone, and for property to be guaranteed by law: yours would be guaranteed, if you possessed it.

But what does Fourier say about these fundamental facts of civilization, the family and labor? The family is cuckoldry; wealth is fraudulent bankruptcy; work is a repugnant constraint. From conceptual abstraction we move on to fact. Irony plays its part here: in civilization, no matter what you do, everyone is a cuckold. Fourier listed forty-nine, even eighty types of cuckolds: philosophers who believe in the seriousness of dialectics will easily find a place in this picture. Irony is the failure of comprehensive dialectics, that is, of a certain type of rationality, specifically the Hegelian type.

Fourier's originality stems from the fact that, unlike Marx, he does not attempt to reverse or overturn this dialectic. For the obvious reason that he was unaware of it, but more precisely because he does not think according to its meaning. Reversal is undoubtedly one possible way of returning to the concrete: by practicing it, we discover that the source of the contradictions between the concept, as it is thought, and real life comes from a more fundamental and unnoticed contradiction that taints abstract rationality. The exploitation of one class by another mystifies rationality, such that the real relations are inverted; likewise, the claim of the dominant class to legislate for the whole of society is the inverted image of its real aims, namely, the satisfaction of its particular ends.

But does the reversed dialectic affect the essence? It’s doubtful: the monogamous family, the mainspring of bourgeois society, is once again sanctified by socialist society; meanwhile work, having escaped a certain type of alienation, nevertheless remains identified with effort and civic duty.

However, Fourier made work the driving force of “Harmony” only because it is, by its very nature, attractive; he only attached familism (and not the family) because he saw in this passion the expression of the bonds that can bring grown ups, and especially the elderly, closer to children. In other words, he radically shifts the problem and the method. Let us take a closer look.

His reading begins to disorient and disconcert us, taking us from critical views that effectively foreshadow Marx's style (and to which we therefore have easy access) to poetic reveries and speculations that appear to be pure fantasy — for example, the copulation of planets. And yet these two aspects of his work fall within the same organizational principle, since they are constantly intertwined.

These are two aspects of the same thought, which always thinks everything together. However, the unifying principle of this thought undoubtedly lies elsewhere than where we are looking for it. Since I have chosen to define Fourier in relation to Hegel, I will return to this comparison. What he lacks and what makes him elusive is the driving principle of Hegelianism, which is also at work in Marxism, namely the concept. The concept is the essential element of the historical type of thinking, which understands reason through history. To think conceptually is to think that it is in civilization that we find the advent of meaning, even if it must be by means of multiple contradictions. Remove the concept, and with it retrospective understanding, and our certainties falter. In other words, if the concept is at the base of our certainties this is simply because it is the other side of our consciousness of ourselves.

By ignoring the dialectic and undermining the concept, Fourier undermines that which lies at the heart of our thinking as civilized people and which, whatever we do, positions the thinking subject and its values — the thinking person who understands and reflects, the person, self-consciousness — at the center of the world and as its end.

There is no self-consciousness in Fourier, there is no concept, just as there is no law or desire. These pairs of opposites around which our thinking is organized — consciousness/concept, desire/law — collapse and lose all meaning under the penetrating fixity of his eagle gaze.

And this collapse now points us to another type of rationality, since, not being rooted in the origin of desire, the law takes another form, and the concept shifts, no longer being summed-up in self-consciousness. At this point, structure takes its place.

To understand Fourier, I propose we borrow Claude Levi-Strauss’s expression “intellectual bricolage,” which may be contrasted with dialectical thinking and theoretical conceptualization. Bricolage consists of using random elements and inserting them into a whole, these elements being able to play a different role in another whole. It therefore disregards the meaning and instrumental purpose of an object by giving it a new function. A book can serve as a wedge or a projectile, dew can take the form of a tabby cat, an umbrella can be placed next to the sewing machine on a dissection table.4 Surrealism understood Fourier, obeying the same structure: poetic bricolage. Fourier is a bricoleur in his clarifications and analogies. He tinkers with the genres of turnips, pears, hyacinths when he uses the census of their differences to define passionate groups. He tinkers with nomenclature when he adapts language (strawberries, pears, etc.) to the functions of the groups. He tinkers with gastronomy and war when he invents gastronomic warfare. He tinkers above all with symbolism:

Groups of milky stars represent the properties of ambition.

Groups of planets on suns represent the properties of love. Groups of satellites on planets represent the properties of paternity. Groups of suns or stars represent the properties of friendship.

But ambition, love, paternity, and friendship can enter into other combinations and form part of other groups: that of colours, plants, animals — and resemblance, if it does play a certain role (cabbage, for example, is an emblem of mysterious love through its nested leaves) is less important than the order that combines objects as elements in a signifying chain. It is the formal structure of the group that gives the elements their possibilities of permutation. Any signifier in one group can become a signified in another. So, there is no longer any absolute reference point as in the dialectic of the concept.

This mode of thinking is precisely what characterizes mythical thinking, which classifies objects and kingdoms (animal, vegetable, mineral), qualities and regions of space, with each part becoming meaningful only in the relationships in enters into. Like myth, Fourier’s restructuring of the world is disconcerting, but it is not without reason; however, the question we should ask is not whether it is true or false, since it is based different logic than bivalent logic; it cannot be verified, and is legitimate only from the perspective of a junction [jonction].

But now that we have discovered its function, we escape the myth that led us to it. For Fourier's thought, even in its most aberrant analogical classifications, is not mythical; while similar in form to mythical thought, it differs in purpose and meaning. The purpose of myth is to reinforce social integration into a given, real order; its meaning is to refer to a system of matrimonial exchanges. But Fourier overturns the real order and frees human relations from the law of marriage and kinship. I see this liberation indicated in the displacement of the classifier that serves to construct the myth. For example, the classifier (the basic class on which the correspondences are built) is chosen from the animal kingdom, itself divided according to a bipartite system, following the divisions between the profane and the sacred, the pure and the impure, the licit and the forbidden. This is why myth is at the origin of repressive civilizations.

Fourier's myth, on the contrary, should help to destroy civilization. And it would do this by changing the classifier, by reversing the order and values. Indeed, the myth with an animal classifier is oriented towards individuality, to which it assigns a place by identifying it. Its function is to facilitate individual identification while connecting the individual to the universe. The individual will then, by entering into a social structure, play the role of a localized element in the system of exchanges.

For Fourier, individuals do not need to be identified, i.e., treated as a signs: on the contrary, they expect their transition to the next stage of society to liberate their latent powers. If they remain signs, however, through their connection to the universe, these signs no longer fall under the law of exchange but under that of attraction. This is why the classifier is not to be sought elsewhere than in what constitutes the individual as a system signifying the universe and signified by it: “Everything, from atoms to stars, forms the tableau of human passions.” The myth, if we can retain this word here, derives its meaning from the function it assumes of revealing individuality to itself, beyond (or below) its factitious identification with a single name, a single place, a single activity. The individual is divided into as many regions as there are passions within him that signify him in relation to the world. And it is by virtue of the possibility offered to him of entering, through the development of these passions, into the greatest number of possible combinations, that he will gain his individuality. This brings us to Fourier's central intuition: that all the passions are articulated through unityism [l'unitéisme], which is not, strictly speaking, a passion, but the source from which passions emanate and the end to which they lead, and which is also described as a journey that leads the individual from pleasure to pleasure and from passion to passion. What civilization condemns as dispersion is here recognized as expansion. This is because, strictly speaking, it is no longer the indivisible subject who "enters" a structure that is in principle foreign to it. The subject is itself structured in a manner homologous to the structures of order that are thus, at all times, nothing more than its expression.

In the final analysis, everything is therefore resolved into structural relationships, cosmic and social attractions alike. Once the civilized illusion of the interiority of the self, of its impenetrability or its transcendence, has been destroyed, formal structure ceases to be contradictory to what is most concrete and most intimate in enjoyment [jouissance]. On the contrary, it allows us to attain it and offers it infinite possibilities for development. In the same way, work becomes attractive only because the establishment of measured series corresponding to a structure of order makes it possible, by linking various works to various passions, replacing the law of effort with the law of attraction and breaking the servitude that attaches the unity of the individual to a single permanent task.

Fourier rightly saw in his mathematical theory the final justification of his system: “The calculus of harmony is a mathematical theory of destinies.”

However, he was wedded to the image: he stopped at the theory of musical sounds based on the twelve-tone keyboard, which serves him universally as a model: “The entity linking number to sensation, the only possibility of experiencing number spiritually, is number as tone, which alone creates the link, the bridge between thought and sensation.” And he was not wrong to begin his reflection with such a connection. All the more so given that musical sound, like passion, can never be isolated, and only derives its meaning from the structure into which it enters as an element. But by cleaving to the image and applying it with excessive rigor, seeking everywhere to reduce the qualitative phenomenon to a numerical magnitude, he remained a prisoner of the arithmetic of whole numbers, where modern mathematics would doubtless link the harmonic progression sought to an algebraic structure.

However, he is less a prisoner of numbers than one might think, which are essentially used in his work to connote the notion of order. And the theory of modules detaches the latter from numerical implication, above all through the application it suggests of the laws of structure to all that comes under a classification that is no longer linear, but combinatorial; in the series and right down to the signifying chain (prose, verse, and letters and syllables). Here, his ingenious bricolage explicitly points to a new algebra: “It is probable that algebra will have to imitate this method, and seek in the serial mechanism the emblems of the new road that will have to be followed” (Universal Unity, L. III, section V).

But perhaps, rather than discussing his number mysticism and musical harmony, we should be astonished at how, with such an imperfect instrument, he was able to go so far, to unravel the meaning — veiled in the more perfect contemporary applications of social mathematics — contained in his first, and still misunderstood, logical scheme of the correspondence between the formal and the sensible. For, through the structuring of the subject that it provokes, this meaning is nothing other than the awakening to an as yet unknown form of freedom. This structuring presides over the disappearance of morality and repression.

In Fourier, one discovers perhaps the only valid answer to the now commonplace argument that the satisfaction of the passions, and in particular the passion of love, weakens the social bond; that there is a contradiction between this satisfaction and the output of production. The most serious explanation of this logic of civilization was furnished by Freud. Its interest lies in the dissociation he makes between work as a reality principle and the pleasure principle. But the insertion of work, conceived according to the structural law of series, into the general field of attraction, modifies these givens. This association takes place at a twofold level: firstly, in so far as the object of work is linked to a primary satisfaction, which is the principle of groups founded on sensory passions; secondly, in so far as all partial work enters into a series that facilitates the satisfaction of other sensory passions, and associates the affective and distributive passions with them.

Attraction then stems from the rivalry and erotic interest presented by the associated individuals. As the law of series is applied from childhood, it leaves no room for dissatisfaction or repression within the individual. The repressive, guilt-inducing superego disappears with the disappearance of paternal authority and the family as a social structure. We can then understand how certain forms of collective organization, constraining in another context (competitions, ceremonies), while presenting themselves in their formal rigor, lose the afflictive character that taints sublimations of this kind, when, through the return of the repressed that they imply, they leave the way open to this civilization's “discontents,” of which Freud so rightly speaks.

But, I repeat, because we can only gain access to Fourier if we understand the meaning of the rationality that guides him, this radical transformation, which is accompanied by a mutation of values, or rather by the disappearance of what we call value, is only made possible by a new way of thinking about man: one that inscribes unity (unityism) in the lack, or defect, of the subject supposedly unified by civilization, and which defines communication between the members of a society by the precise assignment of the place of each passion, instead of it being that vague, atrophied, falsely sublimated contact which morality and metaphysics propose to us.This is the thought that, intrepidly, defines freedom by the maximum development of each of the passions, and is no longer afraid to link it to happiness: “Happiness is to have the maximum of passions and to be able to satisfy them.”

It’s easy to see why Fourier, the innovator, distrusted a political liberalism based on morality, why his guilt-free religiosity never tainted the essence of his work, why the difference maintained in Harmony between rich and poor no longer has the character of exploitation, as long as it serves as an impetus to throw open the full range of the hierarchy of pleasures. Of course, this is not to say that Fourier sprung out of nowhere: although an autodidact, he nevertheless belonged to a tradition, that of the sensualists of the 18th century and of the Encyclopédie. His passionate keyboards recall Diderot's harpsichord; he read Restif and Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, he borrowed ideas from various mystics and Swedenborg, studied Newton and especially Kepler, etc. Despite his abhorrence of the Conventionists, he retained some of Saint-Just's ideas: like the latter, Fourier could have written: "I believe that the more institutions there are, the freer a people is." Fourier's institutions are the Séries.

But these influences and these connections cannot explain Fourier, nor can he be reduced to them. His teachings break new ground; they neither imitate, nor have they been surpassed. The fate of socialism after Fourier only serves to highlight their importance, revealing all that remains lacking in revolutionary political economy. For a time, Marxists were able to recognize that without the total liberation that Fourier advocates, the revolution would never accomplish more than a change of sign. In other words, the meaning of Marx's doctrine remains open, unlike the closed Hegelian discourse on which it has too long been dependent. Fourier can find his place in this openness.5 Provided, however, that Marxism understands that economic planning is inseparable from the science of the passions, and that it does not seek, opportunistically, a "humanist" complement in morality and religion. To do this, it needs Fourier more than ever to spur it on with his lucid naivety, his irony.

Because it is the whole world that must not only be overturned, but prodded everywhere in its conventions (A. Breton, Ode to Charles Fourier).

June 1966

Translated by Howard Slater

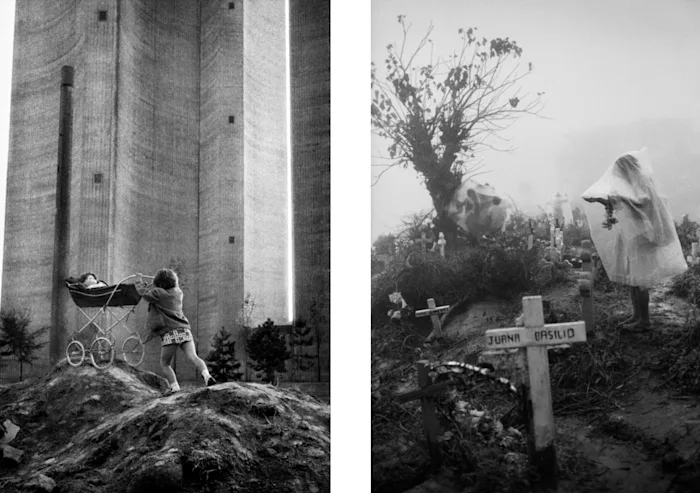

Images: Jean Gaumy

Notes

1. We have adopted Kenneth’s White’s translation. See André Breton, Ode to Charles Fourier, Cape, 1969. —Trans.↰

2. See, in The 120 Days, the presentation of the 150 passions of first class and the 150 of second.↰

3. At the time that I wrote these lines, I knew only by name the unpublished manuscript in the National Archives, entitled The New Amorous World. Since Simone Debout revealed its contents in Les Temps Modernes (July 1966, 1-56), it is appropriate to revisit this restriction, by effectively “granting” to Fourier what his own fear of delivering such audacities to publication and the pusillanimity of his disciples had let us ignore: a perfect knowledge and legitimization of all the so-called crimes and sexual manias: sapphism, pederasty, incest. They already exist in civilization, but are repressed or deviated from; harmonious love will develop them by freeing them from their aggressive implications. Still, the reservation that I made above concerning child sexuality must be maintained.↰

4. A reference to Breton’s First Manifesto of Surrealism (1924): “On the bridge the dew with the head of a tabby cat lulls itself to sleep.” —Trans.↰

5. A text by Marx, directed against a man named Grün, suffices to justify this possibility: “Even leaving aside the conditions in which Fourier lived, Mr. Grün could have studied Attraction more closely, and he would quickly have found that a natural relationship cannot, without calculation, be determined more closely. Instead, he regales us with a literary philippic, stuffed with Hegelian traditions and directed against number.” Karl Marx, The German Ideology, ed. Costes, t. IX, 223. Cited in Raymond Queneau, Bords, Hermann, 1963, 44. ↰