Genealogy of Krav Maga

Elsa Dorlin

The following is a selection from Self Defense: a Philosophy of Violence, which appears in English this month with Verso Books. In it, French philosopher Elsa Dorlin situates the Israeli martial art known as krav maga within a complex lineage of militant Jewish self-defense that developed over the course of a century. Setting out from the desperate heroism of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, before reaching back to radical turn-of-the-century Jewish militias like the Bund, Dorlin shows how the practice of organizing community protection squads against racist pogroms eventually generated a split between radical and reactionary visions of collective self-defense. The origins of Israeli close combat arts are to be found here, in this transformation whereby community self-defense mutates into an offensive political art of governing civil society as a “continuous space of imminent violence.”

Going Down Fighting: the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

The occupier proceeds to the second phase of your extermination. Don’t go blindly to your death. Defend yourself. Pick up an ax, a crowbar, a knife, and barricade your home. Don’t just let yourself be captured! By fighting, you stand a chance at survival. Resist.1

The topographical configuration of the Warsaw Ghetto — its walls rising as high as the second or third floors of buildings and encircling the whole ghetto — was designed to stifle anything happening inside.

And already from the third floor one could see the other street. We could see a merry-go-round, people, we could hear music, and we were terribly afraid that this music would drown us out and that those people would never notice a thing, that nobody in the world would notice a thing: us, the struggle, the dead…[t]hat this wall was so huge that nothing, no message about us, would ever make it out.2

In the ghetto, the Nazis used a special device to detect the sound of voices, in particular when looking for people who had fled and might be hiding in a basement. Resisting this device meant staying quiet. Silence was of vital importance if one was to survive the constant searches, but it also contributed to a form of death beyond the world, a worldless death.3

Concretely, preparing for self-defense in the ghetto involved collecting weapons, hiding them, and arming all the survivors. This was accomplished by buying weapons; by reaching out to the Polish resistance and getting them to smuggle pistols, grenades, and ammunition into the ghetto; by organizing ambushes to capture uniforms and weapons from SS patrols; by crafting homemade weapons (mostly explosives); by building barricades, stashes, tunnels, and bunkers; and by training bodies for combat.4As a space-time outside of the world, the ghetto had become an antechamber of death, where those who had escaped the raids faced certain death and became defenseless ghosts — it would need to be turned into a battlefield.

In September 1942, Menachem Kirszenbaum managed to get the following message out of the ghetto: “We declare war on Germany. This is the declaration of the most desperate war that has ever been waged. Let us see if Jews can earn the right to go down fighting.”5 The Polish police, the SS, and their allies were made to carry fear in their bodies whenever they entered the ghetto, knowing that they were risking their lives and that every one of the living dead they encountered, whether man, woman, or child, was a potential source of armed resistance.6

Calls for self-defense (and the language of battlefields, war, and armed resistance that underpinned them) contributed to a process of rehumanization and stand as an homage to the lives of those in the ghetto: by embracing violence, the survivors wrote their own eulogy. There is no doubt that the decision to embrace violence was a tragic one, leading to a parody of war: the fighters had no chance, the imbalance was insurmountable. However, to act as though it was combat, as though the outcome was yet to be determined, meant dispelling the passive acceptance of death, along with the abyss from which it had come.7

In late October 1942, several meetings were held between members of the different resistance organizations active in the ghetto. The Jewish Combat Organization (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa, or ZOB) was formed in order to “prepare for the defense of the Warsaw Ghetto.”8 In January 1943, its members posted texts throughout the ghetto, reading: “We are ready to die to be human.”9 In the most tragic situation imaginable, human dignity required dying with a weapon in hand — to fight, and perhaps survive, but to become, above all, the heralds of life against death.

Two different vocabularies existed in the ghetto, embedded in the discourse and narratives of the residents and fighters involved in the insurrection. On the one hand, there was the language of resistance, of a counterattack, and of open conflict; on the other hand, there was the language of self-defense: defending their choice of death, defending their humanity, defending selves that were already partially condemned, and always defending the vital principle immanent in the combative reflex.10

“It was always death that was at stake, not life. You see, maybe there was no drama at all there. Drama is when you make a decision, when something depends on you, whereas here, everything had been predetermined.”11 What conditions are required for there to once again be choices beyond those related to survival? If it is even meaningful to speak of choice in such conditions, moving from a choice between life and death to one between types of deaths entails adopting an ethical position in defense of the value of life itself. “Choosing” your death means to die as a fighter rather than be exterminated. In describing the long consultation involved in the formation of the ZOB, notably between Zionist and Communist groups, Marek Edelman wrote:

The majority of us favored an uprising. After all, humanity had agreed that dying with arms was more beautiful than without arms. Therefore we followed this consensus. In the Jewish Combat Organization there were only two hundred twenty of us left. Can you even call that an uprising? All it was about, finally, was that we not just let them slaughter us when our turn came. It was only a choice as to the manner of dying.12

They ultimately chose to defend themselves, not a cause, a territory, or a people, not even a hope. They took up weapons to defend their deaths, and so what was at stake in self-defense was first and foremost another modality of the politicization of life. They decided to choose combat over suicide: most of the resistance fighters considered suicide a waste of bullets that should be saved for the Nazis.13

The idea was omnipresent that it was better to die with a weapon in hand, or at least in combat, even barehanded, than to be gassed or executed by a bullet to the head.14 “We must not think so much of saving our lives, which seems to be a very problematic affair, but rather of dying an honorable death, dying with weapons in our hands.”15 Thus, we can speak of an opposition between thanato-ethics and Nazi biopolitics, which involved the death of entire populations — an organized, industrial, mass extermination of millions of people. Thanato-ethics may be defined as the set of practices wherein death serves as an agent for restoring life’s value.16 Death then becomes a means by which the body, destined to be murdered, regains its humanity.

On April 19, 1943, the Nazis entered the ghetto to carry out an “action” intended to fully liquidate the last survivors: they were met by a thousand men and woman ready for combat who put up a fierce struggle. A clandestine Polish newspaper circulated in Warsaw in April and May 1943 reads:

The Jews are fighting. Not for their lives, since their war against the Germans is one of desperation and despair; their war is about the value of life. Not in order to rescue themselves from death, but over the manner of death — to die like men and not like worms. For the first time in eighteen centuries, they have risen from their humiliation. … The Warsaw ghetto may not be an end but a beginning; whoever dies as a human being has not perished in vain.17

However, Marek Edelman is also critical of the mythology of armed struggle, which he refers to as “symbolic death.”18 Hanna Krall conveys Edelman’s anger:

He screams that I probably consider the people who were surging into the train cars to have been worse than the ones who were shooting. Of course, I do, absolutely, everybody does. Even that American, the professor who recently visited Marek and told him, “You were going like sheep to your deaths.” … He tried to explain … several things — how to die in a gas chamber is by no means worse than to die in battle, and that the only undignified death is when one attempts to survive at the expense of somebody else… My dear, Edelman says, you have to understand this once and for all. It is a horrendous thing, when one is going so quietly to one’s death. It is infinitely more difficult than to go out shooting. After all, it is much easier to die firing — for us it was much easier to die than it was for someone who first boarded a train car, then rode the train, then dug a hole, then undressed naked … Do you understand now? he asks. Yes, I say. I see. Because it is indeed easier, even for us, to look at their death when they are shooting than when they are digging a hole for themselves…19

Léon Feiner was a member and contact of the Bund who survived outside the ghetto by passing himself off as “Aryan” in Warsaw. Regarding the indifference with which their situation was viewed internationally, he said, “We are preparing to defend the ghetto not because we believe the ghetto is defensible, but so that the world will take the desperation of our struggle as a reproach.”20 Léon Feiner repeatedly alerted the Polish resistance and the Allies to the extermination of the Polish Jews and the situation of the fighters in the ghetto. He was the one who transmitted information to the Bund’s representative in the Polish government-in-exile in London, Artur Zygielbojm, who in turn tried every means to incite the British and American governments to act during a conference in Bermuda from April 19 to 30, 1943, while the Warsaw Ghetto uprising raged. On May 12, 1943, Zygielbojm committed suicide in London:

By looking on passively upon this murder of defenseless millions, tortured children, women and men, they have become partners to its responsibility … I cannot continue to live and to be silent while the remnants of Polish Jewry, whose representative I am, are being murdered. My comrades in the Warsaw ghetto fell with arms in their hands in the last heroic battle. I was not permitted to fall like them, together with them, but I belong with them, to their mass grave. By my death, I wish to give expression to my most profound protest against the inaction in which the world watches and permits the destruction of the Jewish people.21

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and its thanato-ethics produced a form of negative heroism that, although resembling fatalism, is marked by the ardent desire for an “us” to survive the horror and annihilation, as well as the world’s obscene indifference. Marek Edelman emphasizes that to go down fighting was primarily an example set for “others,” for his companions: the sight of people ready to die with weapons in hand could pull the terrified residents of the ghetto from their daze.22 To die fighting was the only way for the community to outlive its members.

Self-Defense as National Doctrine

The political history of self-defense by Jewish movements is profoundly tied to their struggles against pogroms, primarily in Russia, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (1881–83, 1903–7, 1917–21). One of the first self-defense groups was formed in Odessa in 1881 on the initiative of a student committee, following the pogroms that occurred after the assassination of Alexander II. The group called itself Yevreyskaya Druzhina (the Jewish militia) and was made up of some 150 men — workers, shopkeepers, and students — who used clubs and iron bars as their weapons.23 After the Bund’s creation in 1897, it became the primary force organizing groups for self-defense against the pogroms. The Bund’s political line was set by revolutionary socialist Jews, and it advocated for defensive violence to protect the Jewish population and their neighborhoods, as well as for measures to educate and organize the proletariat internationally, denouncing anti-Semitism as a counterrevolutionary ideology that divides the working class. Even before the tragic pogrom in Kishinev (in the Bessarabia region of the Russian Empire), the police and army were actively complicit in anti-Semitic violence, arming and protecting the pogromists against whom the Bund was preparing for armed self-defense. Socialist Jewish workers were the driving force behind the self-defense strategy, though it was also supported by non-Jewish workers and organizations, who participated in significant numbers. In August 1902, following the Czestochowa pogrom, the Bund initiated a program to establish self-defense groups everywhere it was active. A few weeks later, a newspaper close to the Bund, Di Arbeter Shtime (no. 30, October 1902) published a text that could be considered the organization’s self-defense manifesto — answer force with force: “We must come out with arms in hand, organize ourselves and fight to the last drop of blood.”24 The analytical framework underpinning these actions was also very clear: “We should do everything we can to spread socialist ideas, specifically that of general liberation, among the Christian masses. This will transform today’s enemies into tomorrow’s friends, creating comrades in the struggle for our ideas.”25The groups organized by the Bund trained for both armed and unarmed self-defense: one widely practiced fighting style at that time was an ultraviolent form of bare-knuckle boxing, without rules or referees, known as kulachnyi boi.26The groups were armed with clubs, stakes, axes, iron bars, and knives. They also trained with firearms, practiced making explosives, and even carried out assassinations against infiltrators from the czar’s police, the Okhrana.27 To be ready in the event of a pogrom, they formed protection and intervention squads, drawing on skills gained serving as marshals during demonstrations and large strikes during the same period.

Self-defense groups were also formed by Zionist workers’ organizations. Their members were mostly craftsmen or residents of semi-industrialized areas where the Bund was not as present, such as southern Russia and Ukraine, parts of Poland, and Crimea. Existing alongside, or in opposition to, the Bund and international socialism, socialist Zionist currents merged to form the Poale Zion in 1901. They developed their own idea of self-defense, oriented toward the defense of their communities and less interested in struggling against anti-Semitic propaganda circulating within the working class.28

The Kishinev pogroms were a turning point.29 On April 6 and 7, 1903, Passover was held in the context of a relentless anti-Semitic campaign around the supposed ritual murder of infants by Jews. With police encouragement, armed groups led a crowd of 2,000 people into Kishinev, home to 50,000 Jews.30 Police prevented a 150-person self-defense group from intervening, arresting many of them and forcing them to disperse.31 Thirty-four men, seven women, and two babies were massacred, while hundreds of others were injured and more than 1,500 homes and businesses were ransacked. Many women and girls were raped and some were tortured, including by having their breasts cut off, and some children were horribly mutilated.32 The outcry from Jewish parties and organizations in Russia was fierce, and they were joined by intellectuals and the international press, but despite this, none of the killers were ever punished.33 All the investigations were botched, and the prosecutions went nowhere, in spite of the commissions formed by Jewish organizations to collect evidence. As part of one such commission based in Saint Petersburg, the poet Hayyim Nahman Bialik spent over a month collecting testimonials and photos and compiling them in a 200-page document for publication. Inspired by this experience, in 1904 he wrote the poem “The City of Slaughter”:

Unto the attic mount, upon thy feet and hands; Behold the shadow of death among the shadows stands. There in the dismal corner, there in the shadowy nook, Multitudinous eyes will look Upon thee from the somber silence — The spirits of the martyrs are these souls, Gathered together, at long last, Beneath these rafters and in these ignoble holes. The hatchet found them here, and hither do they come

To seal with a last look, as with their final breath, The agony of their lives, the terror of their death. Tumbling and stumbling wraiths, they come, and cower there Their silence whimpers, and it is their eyes which cry Wherefore, O Lord, and why?34

This long poem became a symbol of the victims’ passive acceptance:

For great is the anguish, great the shame on the brow; But which of these is greater, son of man, say thou.

The poem was widely read after being translated into Russian and Yiddish, and it has had an enduring legacy. Despite — or perhaps because of — its tone, it marked a shift from horrified despair to cries for revolt, which breathed new life into the drive for self-defense. In Vilnius, Michael Helpern, a prominent member of Poale Zion, recruited and trained self-defense groups under the rallying cry “Remember the shame!”35

Between 1903 and 1905, the Bund and Poale Zion initiated a clandestine program of active cooperation. The two organizations collaborated in the formation of dozens of self-defense groups, called BO (Boevi Otriadi, or combat detachments):

Military and paramilitary training sessions were conducted in safe locations, such as on islands in the Dnieper … When we anticipated a pogrom, the groups were contacted by telephone so they could gather and prepare to counterattack. And so it was in Vilna, Warsaw, Rostov, Minsk, Gomel, and Dvinsk [modern Daugavpils]. The self-defense groups were made up of young factory workers, carpenters, locksmiths, butchers, and other trades, and they also fought against the police, managing to free their arrested comrades on several occasions.36

By 1905, there were self-defense groups active in forty-two cities.37 They faced intense brutality, but the Jewish organizations’ defensive strategy allowed them to resist anti-Semitic violence and to prevent or hinder some pogroms.38 However, police persecution, the imprisonment and deportation of activists, the repression of union activities, increasingly difficult social conditions, and the revolutionary context led to the gradual disbanding of self-defense groups. The murderous pogroms from 1903 to 1905 triggered a major wave of immigration (sometimes called the second Aliyah) to the United States and, to a lesser extent, Palestine, where many Zionist militants with experience in self-defense groups in Russia put their knowledge to use.

This moment makes the distinction between two different ideas of self-defense very clear: that of the Bund (which tried to maintain its activities in Russia in spite of the repression) and that of the Zionist parties. The same split also occurred within the Zionist movement more broadly. There was a conflict between the socialist and cultural strains of Zionism and those that were ultraconservative, nationalistic, or even fascistic. The former lost the ideological struggle, which saw the rise of a militarized and terroristic form of colonial Zionism.

The translation into Russian from Hebrew of Bialik’s poem cited above was done by Ze’ev Vladimir Jabotinsky, then a young writer and journalist.39 Jabotinsky was very active in the Zionist movement and participated in self-defense groups in Odessa in the 1900s. During the First World War, he advocated for an alliance with the British and launched a paramilitary organization, the Jewish Legion, whose goal was to conquer Palestine. During the rioting in April 1920, he was once again at the head of self-defense groups, this time in Jerusalem — these groups had trained at the Maccabi Jerusalem sports club. He was sentenced to fifteen years in prison by the British but was freed the following year.40 He left for London, then traveled to Paris.41 In 1925, Jabotinsky created Hatzohar, the Revisionist Zionist Party, representing the far-right, fascistic current in the Zionist movement, with its headquarters in Paris.42 He was one of the great theorists of a nationalist and authoritarian vision of self-defense that became dominant in Israel, a vision he continued to practice and promote throughout his life, as spelled out in his text The Iron Wall.43 Jabotinsky’s Zionism involved building an offensive Jewish armed force that “the native population cannot breach” and that would be capable of imposing an asymmetrical power structure on “the Arabs” in order to force them to accept the new borders of a Jewish state. His ideas would become dominant through the Haganah (The Defense), an organization he cofounded with Eliyahou Golomb in 1920 as an outgrowth of the Hashomer (The Guardian) that was dissolved that same year. The Hashomer had been a small, composite force founded by Israel Shohat in 1909 to defend the Yishuv — which from 1880 referred to Jewish immigrants who arrived in Palestine as part of the Zionist project — and had been targeted for repression by the Ottoman authorities. Its replacement by the Haganah in the 1920s signaled a shift: the Haganah’s mission was no longer “defending” the Jewish population, but ensuring the Yishuv’s growth, leading the Haganah to gradually become an offensive militia, a paramilitary force that targeted armed groups and the Arab resistance. The Haganah had no legal existence (the British forbade both Jewish and Arab residents of Palestine to organize autonomous armed groups). Still, many Jews of the Yishuv were involved in the British auxiliary police force (the Notrim, a Jewish police force founded by the British in 1936) and so had access to training in hand-to-hand combat (jujitsu). They also learned the basics of military counterinsurgency and offensive combat in the Special Night Squads, which were created in 1938 during the Arab Revolt as special forces under the command of a pro-Zionist British officer, Orde Charles Wingate.44

In 1931, a split within the Haganah led to the creation of the Irgun Tsvai Leumi(National Military Organization), known as the Irgun. This split was the product of a conflict over the ethical principle of “restraint” (havalga) that existed within the Haganah, whereby any “response” against the Arab population must be strictly defensive.45 From 1937, the Irgun followed an increasingly radical path, carrying out deadly terror attacks against Arab civilians.46 The Stern Gang emerged from far-right, nationalist currents of Zionism close to Jabotinsky and the Betar movement, but in its actions it went far beyond Jabotinsky, who had chosen to stand down his troops, both to avoid putting the backs of the British against the wall, and for strategic reasons. In Jabotinsky’s vision, offensive self-defense should not indulge in blind attacks, which disperse energy, wasting it on anarchic, spectacular actions that in practice do little to neutralize “the enemy.”

And so the foundations of Israeli close combat were laid: the civil sphere was to be considered a continuous space of imminent violence. Jabotinsky conflated the situation of Jewish communities in Russia, threatened by pogroms, with that of Jewish militias and soldiers in Israel and their concerns about the Palestinian population and so-called Arab terrorists. Self-defense was, in his view, a way of being: the world is a violent place; this violence traverses every person and they will inevitably enact it; and combat techniques allow for effective and prompt control of the intensity of this violence.47 In the context of a colonial conflict presented as a war on terrorism, you are always exposed to danger with no chance of retreat (close combat) and so must be ready to react to sudden attacks.48 You must always make use of all your physical, sensorial, emotional, and environmental resources to neutralize any possible exogenous source of violence, while adapting to any context or situation, to any kind of threat or enemy.49 On the scale of the nation, one still being established, such a politics of self-defense comes along with a set of defensive practices of self, which force you to live in the immanence of reflex reactions, muscular tension, and emotional connection, to suspend your discernment in regard to complex social relations, historical situations, intentions, meanings, and contexts. This impoverished world gives rise to a “cosmology of terror and total war” that encloses the defensive individual in a hand-to-hand phenomenology of lethal bodies.50 Self-defense becomes a politics, literally a way of governing — at the scale of our bodies — the intensity of violence.

Genealogy of Krav Maga

Imi Lichtenfeld, the inventor of krav maga, a self-defense technique currently enjoying prolific success, was born in 1910 in Budapest, then a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His family moved to Bratislava, Slovakia, where he grew up. His father, Samuel Lichtenfeld, had joined a traveling circus at age thirteen, where he learned a number of gymnastic and combat techniques. He spent nearly twenty years with the troupe, performing feats of strength (including weightlifting) and wrestling. When he returned to Bratislava, he founded Hercules, the city’s first wrestling and weightlifting club, and became the lead detective of the local police force. There, he trained the police in self-defense techniques for immobilizing suspects during arrests. In 1928, Imi Lichtenfeld won the Slovakian junior wrestling championship, and the following year he won the adult title. He also competed internationally in wrestling, boxing, and gymnastics. Alongside this, he taught gymnastics to major theater troupes — notably in Czechoslovakia — and even acted in several plays. In response to the rise of anti-Semitic groups in the 1930s, Lichtenfeld participated in the defense of Jewish neighborhoods during pogroms and became the leader of a self-defense group in Bratislava. He gained experience in unarmed combat in fights against fascist militias. This trajectory is an example of “desportization,” as the boxing and wrestling techniques he had learned were transported from the realm of sports to that of self-defense, from the ring to the street.51

In 1940, Imi Lichtenfeld left Slovakia aboard the Pentcho, the last ship to depart for Palestine, along with 400 other Slovakian Jewish refugees, on a trip paid for by the main right-wing nationalist Zionist party.52 It would take Lichtenfeld two years to reach Palestine. On the way, the boat was repeatedly stopped and quarantined, before sinking off the coast of Greece. Lichtenfeld was rescued by a British ship and spent several months recovering in a Jewish hospital in Alexandria, Egypt. He then enlisted in the Czech foreign legion, which had been placed under British command, and fought on various fronts in the Middle East, including Libya, Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon. In 1942, he received a permit to enter Palestine, where he proceeded to join the Haganah.

This is how the story of krav maga begins, and it is something of a founding myth for the Jewish state. Imi Lichtenfeld is a perfect narrative subject for the history of the self-defense system he developed in the units that would go on to become the Israeli army. The mythic biography of this one man linked the resistance of European Jewish youth to the rise of fascism, and the suffering it inflicted on their communities, to the providential birth of a nation that portrays itself as beset on all sides by attackers but that has managed to establish its existence, its authority, and its borders solely through the strength of its people. This new people, fully engaged in the military, celebrated the heroism represented by their shift from defense to offense. Self-defense in this context meant advancing, gaining ground, striking at the heart of the adversary, with an economy of means necessitating quick, efficient, and incapacitating attacks. Our hypothesis here is that a specific tactical understanding of close combat served as the foundation for a large-scale political and military strategy, or at the very least inspired the vocabulary of its propaganda. Krav maga symbolizes the national ideology of offensive defense, of a war of conquest waged in a context where an army came to define itself as a nation engaged in self-defense, against everyone, in order to survive.

In 1941, an elite, professional unit was formed within the Haganah. Known as the Palmach (an acronym for Plugot Mahatz, the strike force), it carried out targeted terrorist attacks, which were termed offensive self-defense. Due to a lack of logistical resources (wooden weapons were often used during training), this emerging force focused on techniques for hand-to-hand combat and developed its own training program. The same year, kapap groups (an acronym for krav panim el panim, “face-to-face combat”) were established in both the Haganah and the Palmach. They were led by Gershon Kopler (jujitsu and boxing), Yehuda Markus (jujitsu and judo), and Maishel Horowitz (stick and knife fighting), nearly all of whom had served in the Special Night Squads.53 The following year, Imi Lichtenfeld was recruited to the Palmach by Musa Zohar and became their kapap instructor — he taught jujitsu, boxing, and knife-fighting techniques. During this time, a particular strategic vision of offensive self-defense was coalescing among the leaders of what would become the IDF (Tsva ha-Hagana le-Yisra’el, the Israel Defense Forces), which would be founded in 1948 by merging all the existing paramilitary forces.54

Rather than a more traditional static defense along a front line, the IDF excelled in incapacitating lightning attacks, intended to stun the enemy and throw them into disarray, and in concentrated offensive actions to neutralize the enemy’s center using (exclusively male) units with intensive training in hand-to-hand combat.55 Despite its reputation as being ragtag and improvised, the IDF developed a novel self-defense strategy as part of its broader policy of colonization that would go on to be exported and recognized as one of the most effective counterinsurgency strategies in the world. Whether applied to an individual, a group, a militia, or an army, to civilians or to soldiers, whether it is termed sexual violence, criminality, or terrorism, the principle remains the same. Israel thus became a working model of a “security society,” in which participation in paramilitary self-defense practices would soon lay the bedrock for a securitarian civility.56

The term krav maga (close combat) appeared in 1949 and was used alongside kapap. In 1953, Imi Lichtenfeld was part of a group that began codifying an unarmed combat system based on thirty-five basic techniques that were constantly renewed, tested, and adapted to the current situation. In 1958, he became the military’s lead krav maga instructor. Krav maga became the official name for the defensive combat system used by the IDF, and soon it was a profitable military export. In 1964, Lichtenfeld left the army and founded the first civilian krav maga club in Netanya, where he continued developing its core practices, based on four main precepts: adaptability (to situation and context), effectiveness (in defense), universality (usable by everyone), and spreadability (in the national culture).57 Since the 1980s, krav maga has been promoted around the world as the most “realistic” unarmed self-defense system, and also as one of the most profitable Made in Israel products. But krav maga is also so much more than this: it is a practice of self, a civic practice, and a national culture, in a context where its generalization helps maintain a world in which krav maga is the only possible way of being. Its reputation as the most practical technique, the most realistic, for self-defense is not the only reason for its success: its spread coincides with the generalization of a culture of defense. This has transformed civil society itself, along with each individual’s experience of the world. Krav maga is a realistic combat technique insofar as it produces a reality in which it can be presented as the only viable approach to life.

Krav maga has also been used to produce a set of derivative techniques that are marketed to the public police forces around the world. These techniques complement — or in some cases upend — older counterinsurgency practices in two important ways.

Firstly, offensive-defensive close combat can conceal the fact that deadly weapons are being used, which can incite public outrage should it gain media attention. This is achieved by transforming the body itself into a deadly weapon, capable of using a small number of techniques to immobilize another body using anatomical “pressure points,” producing paralysis, unconsciousness, or suffocation. It can also involve supplementing the lethal body with extensions (such as tonfas, Tasers, Flash-Balls, or dogs) that are supposedly nonlethal. Mathieu Rigouste showed that equipping police with these “less than lethal” weapons constitutes a decision to legalize murder, under the pretense of expanding the police’s right to self-defense.58

Secondly, the spread of close-combat techniques changed the traditional practice of creating distance between police and disorderly situations. Creating distance involves principles of “defensive passivity” (such as police lines or filter cordons during demonstrations), the imposition of self-restraint (including dispersal techniques), or delegating the force of strikes to an instrument (for instance, a water cannon).59 The spread and promotion of a public order strategy emphasizing hand-to-hand techniques contributed to a renewal of virile norms privileging deadly contact, shock, intrusion, infiltration, provocation, humiliation, and disorganization, thereby transforming the police officer’s body into an offensive body.60

This creation of offensive bodies also results from a chemical transformation of the fear that inhabits the police, and which they help to spread, into a repressive dynamic that lays the groundwork for a new dominant virility.61 As a value, fear has long been tied to effeminate, cowardly forms of masculinity, but here it has morphed into a source of virility, constructing bodies ready to defend themselves at the slightest of chemical signals, transforming the instinct to freeze into a trigger for attack.

The generalization of krav maga in Israeli civil society alongside the theory of offensive defense, in which any good defense is also an attack, has elevated the spirit and letter of techniques for self-defense in real situations — a core principle of the Israeli state’s military strategy — to the level of national motto. Its spread also carries with it a macho, bellicose vision of citizenship, which invokes the principle of defense of self to legitimize its right to violence and colonization.

More broadly, modern Israel is a political model, both civic and civil, of how governance can transform in response to a force that typically leads to crisis or failure for the security state: a terrorist menace.62Terrorism provokes widespread fear, but when this becomes a virtù, it favors policies that can control fear by means of fueling the feeling of insecurity in civil society, and therefore also in its individual members, rather than providing defense or protection. Such policies are quite economical, since individuals become responsible for defending themselves, for embodying the use of violence and becoming defensive bodies. They can then be usefully transformed into deadly martial units, atomized and tasked with vigilance against a faceless enemy, willing to be governed by fear in the name of security.

Elsa Dorlin’s Self Defense. A Philosophy of Violence comes out this month with Verso Books.

Translated by Cédrine Michel and Kieran Aarons

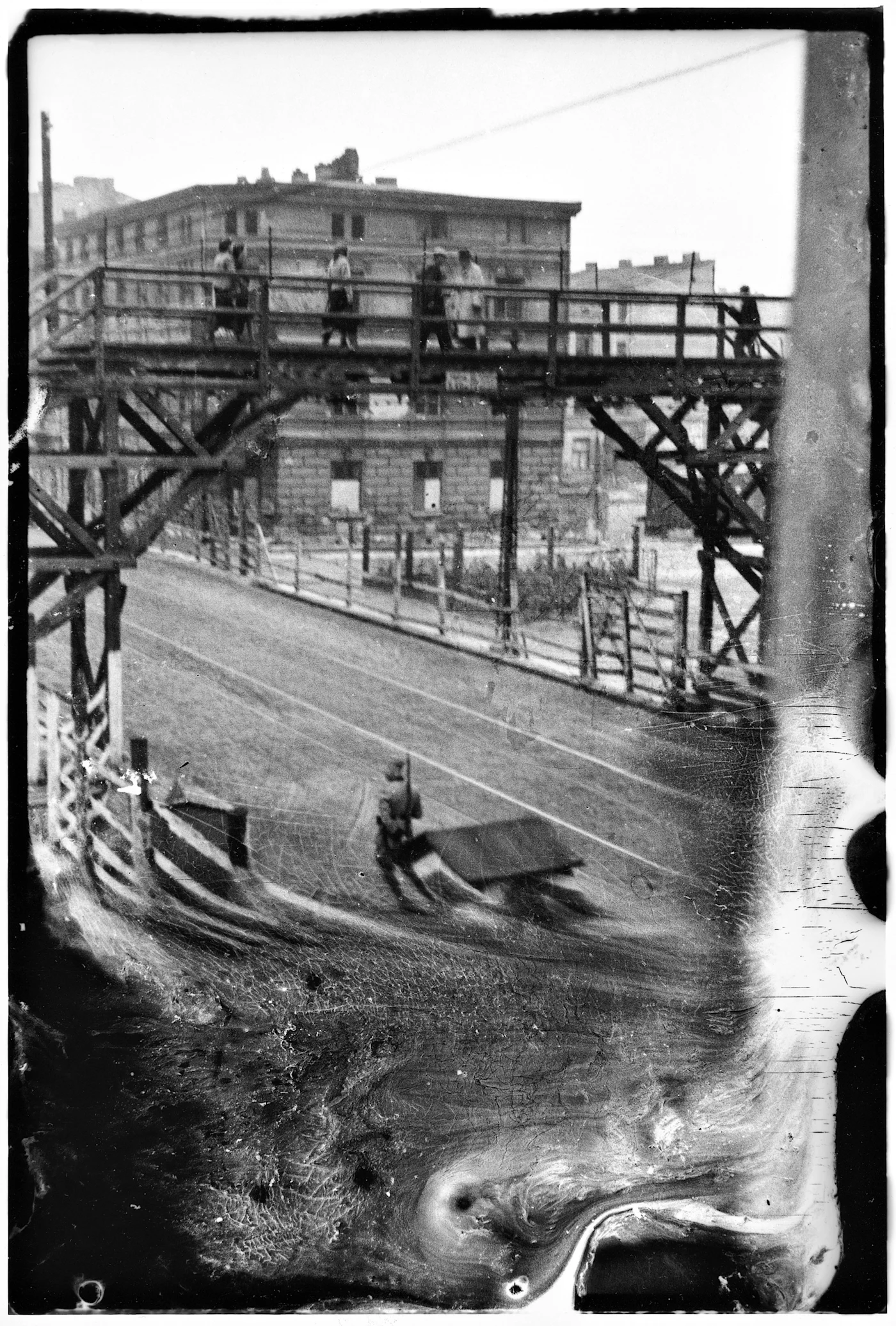

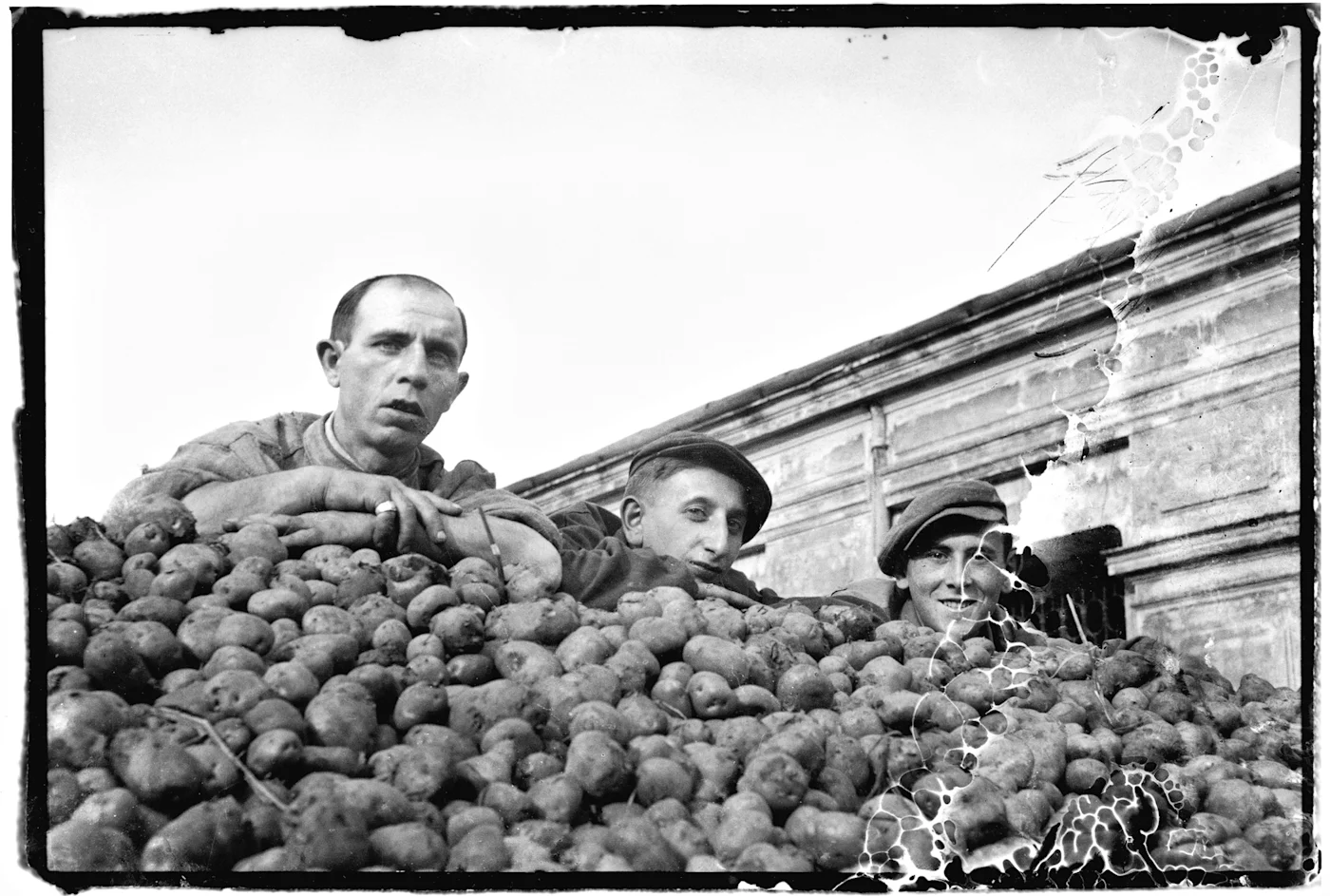

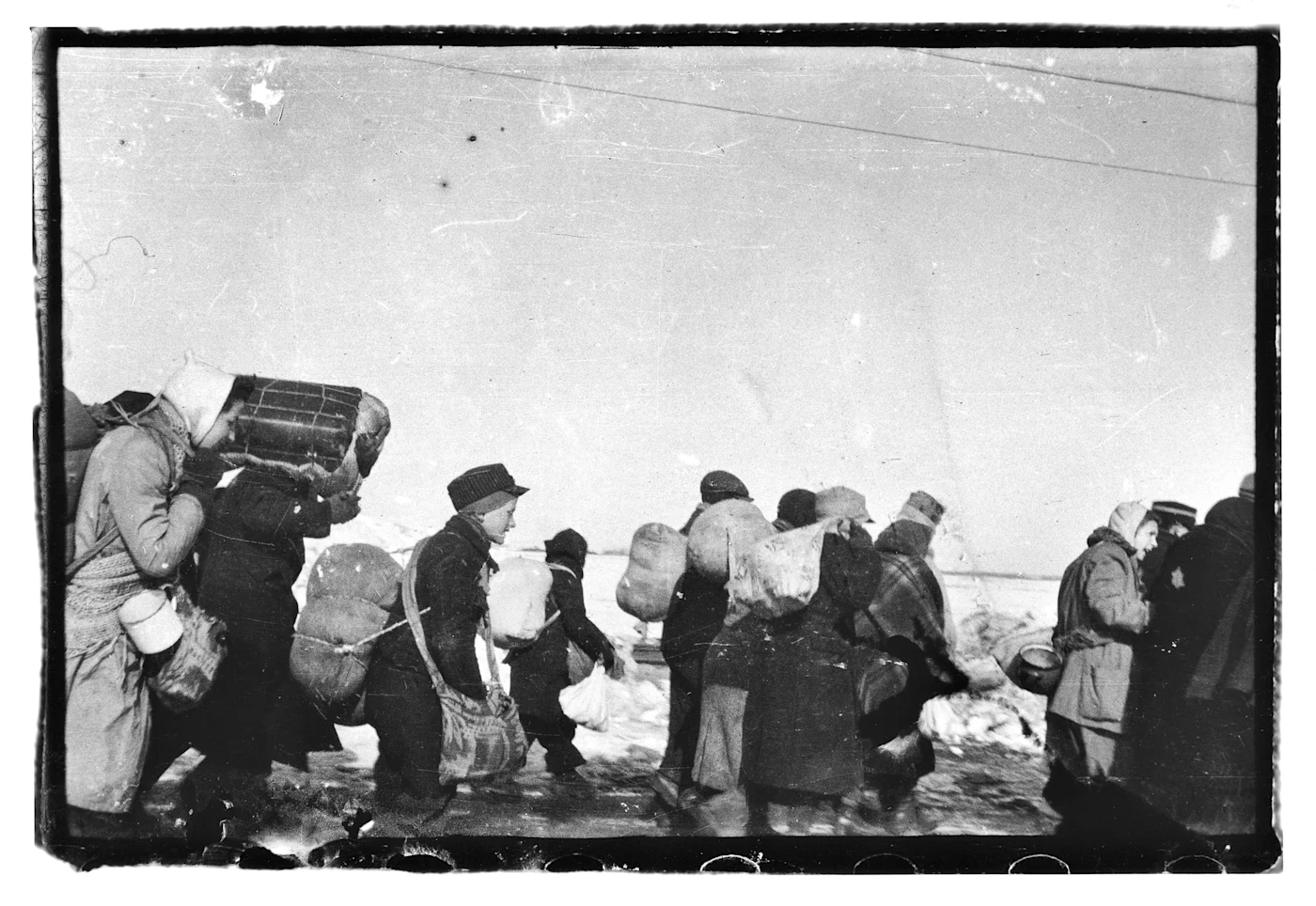

Images: Henryk Ross

Notes

1. From a set of documents retrieved from the Ringelblum Archives in Warsaw, Poland. Document number 426. Ring II/333/ Mf/ ZIH-802; USHMM-57. Translated into French by Ian Zdanowicz. My thanks to Ian Zdanowicz for pointing these documents out to me and translating them. Thanks as well to Tommy Kedar, who brought several important sources to my attention.↰

2. Hanna Krall, Shielding the Flame: An Intimate Conversation with Dr. Marek Edelman, the Last Surviving Leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, trans. Joanna Stasinska and Lawrence Weschler, Henry Holt and Co., 1986, 7.↰

3. I am referring here to Hannah Arendt’s idea of worldlessness. See Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, University of Chicago Press, 1958.↰

4. The Armia Karjowa (the largest organization resisting the Nazis in Poland) provided “90 pistols with ammunition, 600 grenades, 15 kg of plastic explosive, and a few automatic rifles. The Polish Workers Party sent 10 rifles and 30 pistols … We can safely say that the support given by the Polish Resistance was minimal. The Jewish fighters were to remain tragically isolated. Henri Minczeles, Histoire générale du Bund: Un mouvement révolutionnaire juif, Denoël, 1995, 339.On the arms and equipment collected by self-defense groups, see Emmanuel Ringelblum, Ktovim fun geto, vol. 1 (1961), 332–3. Cited in Yisrael Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw, 1939–1943: Ghetto, Underground, Revolt, trans. Ina Friedman, Indiana University Press, 1982, 349–50.↰

5. Cited in Minczeles, Histoire générale du Bund, 339.↰

6. Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw, 315–16. ↰

7. See Journal byHirsch Berlinski, a fighter from the ZOB (Jewish Combat Organization). Cited in Rachel L. Einwohner, “Availability, Proximity, and Identity in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising: Adding a Sociological Lens to Studies of Jewish Resistance,” Sociology Confronts the Holocaust, Duke University Press, 2007, 286. ↰

8. See Hirsch Berlinski, Zikhronot (Yalkut Moreshet, 1964), 14–16. Cited in Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw, 287. Another armed organization was also formed, the Jewish Military Union (Zydowski Zwiazek Wojskowy — ZZW).↰

9. Ibid.,305.↰

10. [On related themes, see Wladyslaw Szlengel, “Counterattack,” trans. John Carpenter and Bogdana Carpenter, Chicago Review 52, no. 2/4 (August 2006): 287–91. — Trans.]↰

11. Krall, Sheltering the Flame, 6.↰

12. Krall, Sheltering the Flame,10.↰

13. “He had a girlfriend. Pretty, blond, warm. Her name was Mira. On May 7 he came with her to our place in Franciszkanska Street. On May 8 he shot her first and then himself. Jurek Wilner had apparently declared: ‘Let’s all die together.’ Lutek Roblat shot his mother and sister, then everybody started shooting. By the time we managed to get back there, there were only a few people left alive; eighty people had committed suicide. ‘This is how it should have been,’ we were told later. ‘The nation has died, its soldiers have died. A symbolic death.’ You, too, probably like such symbols? ‘There was a young woman with them, Ruth. She shot herself seven times before she finally made it. She was such a pretty, tall girl with a peachy complexion, but she wasted six bullets.’” Krall, Sheltering the Flame,5.↰

14. In January 1943, at a time when there were only 500 members of the ZOB remaining, there was another raid. Only 80 fighters survived. Marek Edelman wrote: “For the sake of exactitude I’ll tell you that ‘our barrels’ from which the fire blossomed — at that time there were only ten of them in the Ghetto … Anielewicz’s group, which was taken to the Umschlagplatz and did not have arms, started hitting the Germans with bare fists. The group of Pelc, the eighteen-year-old printer, when taken to the square, refused to board the train, and Van Oeppen, the commander of the Treblinka camp, shot all of them, sixty men, on the spot.” Krall, Sheltering the Flame,61–2.↰

15. Emmanuel Ringelblum, “‘Little Stalingrad’ Defends Itself,” To Live with Honor and Die with Honor! Selected Documents from the Warsaw Ghetto Underground Archives ‘O.S.’ (‘Oneg Shabbath’), Menachem Press, 1986, 595. ↰

16. Armed self-defense was an ethical gamble, sharing little with the aesthetic of heroism. However, in a clandestine Polish newspaper from April 30, 1943, there is an argument that self-defense and dying with weapons in hand would transform the Jews into a people: “From a helpless people, a flock slaughtered by the German murderers, the Jews have risen to the level of a fighting people. And even if they do not fight for their existence — which is out of the question, considering the absolute superiority of the enemy — they have nonetheless demonstrated their right to national existence.” “The Greatest Crime in the World,” Mysl Panstwowa [Government thinking), April 30, 1943, Yad Vashem Archive, 0-25/25. Cited in Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw, 404. Thanato-ethics thus provided substance to a national mythology, which in subsequent narrative construction would be drained of its original meaning in favor of nationalist rhetoric based in dialecticizing the victim/hero relationship.↰

17. Front Odrodzenia Polski, “Around the Burning Ghetto,” Prawda Mlodych [The truth of the young], April–May 1943, 279–80. Cited in Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw, 406. We see here the idea that for the FOP, although the Jews and Poles have a common enemy in the Germans, their war is not the same. ↰

18. See the classic text by Jesse Glenn Gray in which he discusses this fascination with scenes of battle at length, in reference to Kant’s concept of the sublime. He provides a good example of the excessive aestheticization of combat and how it contributes to the ongoing construction of contemporary normative heroic virility. Jesse Glenn Gray, The Warriors: Reflections on Men in Battle, Harper Colophon Books, 1970.↰

19. Krall, Shielding the Flame, 36–7.↰

20. Minczeles, Histoire générale du Bund, 339. The Bund was founded October 7–9, 1897, near the city of Vilna. Over the Rosh Hashanah holiday, a dozen syndicalist delegates, eleven men and three women, most of them workers and intellectuals from local organizations and clandestine newspapers, met and created the General Jewish Labour Bund (Algemeyner yidisher arbeter-bund in lite, Poyln un Rusland). Their goal was to create a Russian social-democratic party and rally Jewish workers to it. It rapidly became “the only socialist organizational structure with a solid existence east of Poland … The founding of the Bund signaled a new era in the organization of the Jewish proletariat. During the first two or three years of its existence, the Bund called 312 strikes in 14 factories, affecting 44 economic sectors. In 157 of these stoppages, 27,890 workers participated … New relationships were formed between those involved in the socialist project. Transfiguration is not too strong a word, because social-democratic militants distinguished themselves from their fellows through their commitment to purity and to their ideals. This manifested itself in countless details in daily life: physical hygiene, clean clothes, and the refusal of vulgar talk, obscenities, and cursing. This new kind of behavior was also integrated into their relationships with workers, which play an incalculable role in the development of the Jewish workers’ movement. Women … became equals as comrades.” Nathan Weinstock, Le Pain de misère: Histoire du mouvement juif ouvrier en Europe, coll. [Re]découverte, vol. 1, La Découverte, 2002, 116. The Bund reached a peak of 33,000 members in 1906 before being targeted by severe repression.↰

21. Szmul (Artur) Zygielbojm, “The Last Letter from Szmul Zygielbojm, the Bund Representative with the Polish National Council in Exile,” Yad Vashem Archives, O-55 (2016): “To our appeals for help, the outside world sent its answer. Through the underground radio, we received the news that brave and loyal Artur Ziegelboim, our representative with the Polish government-in-exile, had given us the only aid within his power. During the night of May 12 he committed suicide in London as a gesture of protest against the callousness and indifference of the world … The meaning of Artur’s suicide was bitterly clear to all of us. He was tendering us the balance sheet of all his efforts on our behalf. Through an edition of The Bulletin issued on the Aryan side, we let the underground know that another fighter, who had suffered and fought with his ghetto comrades until his last breath, had fallen in far-off London.” Bernard Goldstein, Five Years in the Warsaw Ghetto: The Stars Bear Witness, trans. Leonard Shatzkin, Viking Press, 1949, chap. 6.↰

22. “The important thing was just that we were shooting. We had to show it. Not to the Germans. They knew better than us how to shoot. We had to show it to this other, the non-German world.” Krall, Shielding the Flame, 3.↰

23. Weinstock, Le Pain de misère.↰

24. [We rely here on Shlomo Lambroza’s translation of these phrases. See his “Jewish Self-Defense During the Russian Pogrom of 1903–1906,” in Hostages of Modernization: Studies on Modern Antisemitism 1870–1933/39, vol. 2, Walter de Gruyter, 1933. — Trans.]↰

25. Minczeles, Histoire générale du Bund, 95. See also Henry J. Tobias, The Jewish Bund in Russia, from Its Origins to 1905, Stanford University Press, 1972; I. L. Peretz, “Impressions of a Journey Through the Tomaszow Region,” in The I. L. Peretz Reader, Yale University Press, 2002.↰

26. Stephen P. Frank, Crime, Cultural Conflict, and Justice in Rural Russia 1856–1914, University of California Press, 1999, 157–8.↰

27. Also at play is the distinction between “violence” and “defensive violence,” and in this case, the line is not clearly drawn between self-defense and terrorism. In 1901, during its fourth congress, the Bund adopted a resolution banning terrorist acts. ↰

28. The differences between these two tendencies should not overshadow their commonalities. In 1909, during the Poale Zion party’s congress in Vienna, a motion was passed to establish connections with other Jewish workers’ parties. The support of the party’s leader, Bev Borokhov, was crucial to this, though he drew the ire of Poale Zionists in Palestine, who accused him of abandoning the Palestinian aspect of the party’s program when he declared, “We are not a party for Palestine, but for the Jewish proletariat.” The Russian section of the party thus left the Zionist Organization. See Weinstock, Le Pain de misère, 238.↰

29. The assault lasted several days, spilling over into other neighborhoods and surrounding towns until martial law was declared on April 21. See Monty Noam Penkower, “The Kishinev Pogrom of 1903: A Turning Point in Jewish History,” Modern Judaism 24, no. 3 (2004): 188.↰

30. Local Jewish religious authorities informed the local police of the campaign calling for a massacre, but nothing was done to prevent it. Penkower, “The Kishinev Pogrom of 1903,”189.↰

31. Penkower, “The Kishinev Pogrom of 1903,”187.↰

32. Penkower, “The Kishinev Pogrom of 1903,”188.↰

33. In regard to the reaction of intellectuals, Leo Tolstoy had remained silent during the massacres of 1881–83 but spoke out against the “horrible events in Kishinev.” Maxim Gorky published a collection of essays, Sbornik, and turned the proceeds over to the victims. Ibid.,190. In regard to the international press, see the April 28, 1903, edition of the New York Times.↰

34. Hayyim Nahman Bialik, “The City of Slaughter,” in Complete Poetic Works of Hayyim Nahman Bialik, Histadruth Ivrith of America, 1948, 129. See also The Literature of Destruction: Jewish Responses to Catastrophe, Jewish Publication Society, 1989; and Michael Stanislawski, Zionism and the Fin de siècle, University of California Press, 2001, 183. ↰

35. Penkower, “The Kishinev Pogrom,” 193. See also Lambroza, “Jewish Responses.” ↰

36. Minczeles, Histoire générale du Bund, 98.↰

37. From the “Self-Defense” entry in the Jewish Virtual Library, jewishvirtuallibrary.org.↰

38. In the fall of 1903 in Gomel, a pogrom was prevented by self-defense groups jointly organized by the Bund and Poale Zion, in which 200 combatants drove back the mob and also the army and police, who had been complicit. In Zhytomyr in May 1905, self-defense groups from the Bund were able to limit the horror, although 29 people were killed and 150 wounded. In the fall of 1905 in Ekaterinoslav [modern Dnipro], during the revolution, self-defense groups from the Bund, Poale Zion, and Jewish student organizations drove back the mob and managed to defend not only the Jewish neighborhoods, but also non-Jewish working-class areas at risk of being pillaged and burned. They pursued pogromists who succeeded in robbing Jewish shops or homes. See Theodore H. Friedgut, “Jews, Violence, and the Russian Revolutionary Movement,” Studies in Contemporary Jewry 18 (2002): 52–3.↰

39. Born in Ukraine in 1880 and died in the United States in 1940. See Ze’ev Vladimir Jabotinsky, Story of My Life, Wayne State University Press, 2015.↰

40. Ilan Pappe, Across the Wall: Narratives of Israeli-Palestinian History, I. B. Tauris, 2010, 115.↰

41. In 1921, Jabotinsky was elected a member of the Zionist Organization, though he was critical of its compromises with the British. He was expelled over his secret agreement with the anti-Semitic and anti-Bolshevik leader of the Ukrainian government-in-exile, Symon Petliura. See Marius Schattner, Histoire de la droite israélienne: de Jabotinski à Shamir, Éditions Complexe, 1999, 69. ↰

42. Two years earlier, Jabotinsky had founded Betar (Brit Yosef Trumpeldor,“the Joseph Trumpeldor Movement”), which would go on to become the youth wing of the Hatzohar.↰

43. Ze’ev Vladimir Jabotinsky, “The Iron Wall,” Jewish Herald,November 26, 1937. Available from the Jabotinsky Institute on Israel’s website, under reference number F-1923/204/EN.↰

44. Schattner, Histoire de la droite israélienne, 176. Wingate went on to be a leader of the Chindits, the United Kingdom’s special forces during World War II, and was active in the Burmese Campaign, where he conducted offensive operations far from the front line and ultimately lost his life. Many Israeli politicians participated in the Special Night Squads, including Moshe Dayan (head of the Israel Defense Forces from 1955 to 1958, minister of defense in 1967) and Ygal Allon (one of the first leaders of the Palmach in 1941, minister repeatedly between 1961 and 1977). Moshe Dayan, Moshe Dayan: Story of My Life, William Morrow and Company, 1976, 44–7.↰

45. This “ethical” principle of restraint was also political, because it was the condition Britain placed on the Haganah in return for arming them during the 1936–39 uprising, which was officially illegal. ↰

46. In the same ideological vein, the Stern Gang also emerged from far-right Zionist currents and carried out attacks against the British authorities, going so far as to make overtures to Nazi Germany. The Stern Gang, named for its founder, Avraham Stern, called itself Lehi, an acronym for lehomi herouth leIsrael; Stern founded it in 1940 after a split with the Irgun occasioned by the outbreak of the Second World War and the cease-fire agreement with Britain signed in 1939.↰

47. See Einat Bar-On Cohen, “Globalization of the War on Violence: Israeli Close Combat, Krav Maga and Sudden Alterations in Intensity,” Social Anthropology/Anthropologie sociale 18, no. 3 (2010): 267–88.↰

48. One of the core ideas of self-defense is to break down the notion of safe distance: to be at a distance is to be vulnerable (in range of a kick or a punch, for instance), while being close to the attacker’s body means finding opportunities to strike their vulnerable points (the throat, vital organs, or joints). ↰

49. Physiological and emotional work would become an essential characteristic of krav maga: learning to react quickly, to keep your muscles ready, to turn fear into a trigger for attack rather than letting it be an obstacle to defense. It involves using not only your muscles but also your emotions, affects, and hormones for maximum benefit in a form of fighting chemistry. ↰

50. Bar-On Cohen, “Globalization of the War on Violence,” 269. ↰

51. See Benoît Gaudin, “La codification des pratiques martiales: Une approche socio-historique,” Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 179 (2009); Johan Heilbron, “Dans la cage: Genèse et dynamique des ‘combats ultimes,’” Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 179 (2009).↰

52. For images from the SS Pentcho, see the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s online collections.↰

53. For more information about these instructors and the history of krav maga and kapap, see Noah Gross’s article, “Krav Maga History Interview,” on your-krav-maga-expert.com. ↰

54. David Ben-Gurion envisioned a “People’s Army” and chose compulsory military service as the primary tool for building the Jewish nation and allowing for social cohesion, integration, and solidarity. The choice to enlist women was made partly in response to a lack of men of military age, but also because military service was seen as the only patriotic matrix capable of producing a national community. The army was where one learned Jewish language, culture, and history, alongside training in weapons and military discipline. In practice, behind this facade of inclusion, the Israeli army produced a norm of hegemonic masculinity by normalizing practices and constructing a system of meaning and values that resulted in “spontaneous consent to the patriarchal status quo.” Orna Sasson-Levy, “Constructing Identities at the Margins: Masculinities and Citizenship in the Israeli Army,” Sociological Quarterly 43, no. 3 (2002): 374. Sasson-Levy cites Renate Holub as a source for “spontaneous consent”: Renate Holub, Antonio Gramsci Beyond Marxism and Postmodernism, Routledge, 1992, 6.↰

55. For more about these exclusively male units, see Martin Van Creveld, “Armed but Not Dangerous: Women in the Israeli Forces,” War in History 7, no. 1 (2000): 374. In this article, the author points out that women were excluded from all combat units following a traumatic event in December 1947, when a mixed unit of the Palmach was ambushed and decimated. The bodies of the fighters were found several days later, horribly mutilated. Cited in Vincent Joly, “Note sur les femmes et la féminisation de l’armée dans quelques revues d’histoire militaire,” Clio 20 (2004). The Israeli army is officially gender inclusive, but although women receive military training, it is not the same as the men’s. Most women are assigned to administrative roles, and only a minority become commanders (despite the existence of a special unit, the Hen, or Heil Nashim, the women’s corps, that existed from 1949 to 2001). For an overview of this issue, see Ilaria Simonetti, “Le service militaire et la condition des femmes en Israël,” Bulletin du Centre de recherches français à Jérusalem 17 (2006). [Simonetti also briefly deals with these issues in an English text: Ilaria Simonetti, “Women’s Violence and Gender Relations in the Israeli Defence Forces,” Gender and Conflict: Embodiments, Discourses, and Symbolic Practices, ed. Georg Frerks, Annelou Ypeij, and Reinhilde Sotiria König (Routledge, 2014), 71. — Trans.]↰

56. In regard to “society of security,” see Michel Foucault, “La sécurité et l’État,” Dits et écrits: 1954–1988,vol. 3 (Gallimard/Quarto, 1994), text no. 213: “Societies of security, in their current form, are tolerant of a whole range of different and varied behaviors, even deviant ones and ones that are antagonistic to each other; as long as, of course, these fall within certain boundaries, such that things, people, and behaviors considered unnecessary and dangerous are eliminated.”↰

57. Krav maga, as it emerged in civilian society, had a small number of precepts: “Do not hurt yourself,” “Remain modest” (meaning no needless fights, no overreactions, always control your emotions and affects, and train yourself mentally), “Act decisively” (make the right move at the right time at the right spot, using every advantage presented by the situation and your own resources), “Become as effective as possible” (allowing you not to have to kill). Six principles summarize krav maga’s martial foundation: avoid being hurt and always analyze risk, which is the essence of self-defense; use the martial body’s natural reflexes and movements (never adopt an unnatural level of technical sophistication that takes time to embody or learn to execute properly); react correctly (staying balanced, adapting to the “environment,” while defending by attacking); always strike at vulnerable and debilitating points (reducing the energy and time taken by the fight); use any available object; and do not follow any rules (no technical, deontological, or sporting restrictions). See Imi Sde-Or (Lichtenfeld) and Eyal Yanilov, Krav maga: How to Defend Yourself Against Armed Assault, Dekel Publishing House, 2001, 3–4. See also Gavin De Becker, The Gift of Fear and Other Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence, Delta, 1997. My thanks to Emmanuel Renault for having pointed me to this reference and for our correspondence on martial arts. We have used 1964 as the year Lichtenfeld left the army, but Izhac Grinberg, another historian of krav maga, claims that it was in 1963. See his article “History of Krav Maga,” on kravmagainstitute.com.↰

58. Mathieu Rigouste, La Domination policière, La Fabrique, 2012, 211.↰

59. Regarding defensive passivity, Patrick Bruneteaux mentions that in the case of policing in metropolitan France, such techniques also seek to avoid charging so as not to escalate the situation. See Patrick Bruneteaux, Maintenir l’ordre, Presses de Sciences-po, 1996, 173, 225. See also David Dufresne, Maintien de l’ordre, Hachette, 2007. For self-restraint techniques, see Bruneteaux, Maintenir l’ordre, 105.↰

60. Lesley J. Wood, Crisis and Control: The Militarization of Protest Policing, Pluto Press, 2014.↰

61. In France, the widespread use of plainclothes police units (known as the BAC) and their sudden interventions in working-class neighborhoods has created a climate of fear and insecurity. For the BAC, any act of resistance or opposition is just a chance to react. “‘Fear is unavoidable,’ says Christophe, a four-year veteran of the Seine-Saint-Denis region’s BAC. ‘Even with experience, you never know what you’re going to run into … You could get ambushed and hit with a paving stone from up in a building, or a cinder block, a piece of sidewalk, anything some of these people can get their hands on!’” Rigouste, La Domination policière, 168. This new dominant virility adds to the appeal of combat sports, self-defense, and any “realistic,” “no rules” martial practice, which have become a defensive hexis.↰

62. Michel Foucault, “La sécurité et l’État.”↰