Gimme Danger

P.M.A. Gittlitz & J.F.

In 1967 the suburban teens who would become Iggy Pop and the Stooges were living in the dull college town of Ann Arbor, Michigan when they heard about the insurrection in Detroit. It was one of the most violent riots in American history, requiring 7,000 national guardsmen to quell. Forty-three people died. Whites fled the city by the tens of thousands. By contrast, the white Stooges headed into town with little more than their guitars and a shovel to open a communal squat. There, more than any other band, they defined what would soon be known worldwide as punk rock.

Today, as in the late ‘60s, danger is in the air. First it came as microparticules spewed from the orifices of the often asymptomatic infected. Without knowing who was a spreader, and how long the air could be contagious, just about everyone’s best guess was to stay inside as much as possible and cover oneself in prophylactics for rare ventures outside. Much of social life shut down, but the economy remained thanks to those “essential workers” with the dubious privilege of keeping their jobs. While the lucky among the laid-off received unemployment and stimulus checks, the less bureaucracy-savvy lost their basic lifelines.

Among them was George Floyd, a poor Black man infected with Covid and murdered by the Minneapolis Police for allegedly passing a counterfeit bill at a local grocery store. While deaths like Floyd’s are routine in a country where a plurality of people are treated as disposable, especially Black people, Floyd’s death ignited a general social condition of fear, anxiety, frustration, and rage into a national rebellion the likes of which the US has never seen. It began when Floyd’s neighbors defied the Covid restrictions when they poured into the streets, burned down the police station where the murderers worked, and systematically looted, burned, and otherwise vandalized any business that the crowd did not deign worth leaving alone. One shirtless protester, reveling in the flames of Minneapolis, declared: “Covid is over!”

The image became contagious, and riots spread across the country. People laid siege to bastions of capital and the state, radically contesting the use of public space amid a national lockdown. Stores were ransacked from Beverly Hills to Manhattan’s chic Soho district. Cop cars burned in dozens of towns. CNN headquarters in Atlanta was besieged by a proletarian mob. Thousands of protesters briefly breached the gates of the White House, forcing Trump into a subterranean safe room.

The atmosphere of the George Floyd Rebellion was often tense and chaotic. An arsenal of fireworks preposterously pounded the night from coast to coast for a full month while people built autonomous zones behind armed barricades to contest the state-sanctioned uses of public space. Millions put their bodies on the line to reject the racial order of American capitalism and to reclaim spaces like roads for subversive activity ranging from nightly vigils to protracted riots. Republicans called for a military invasion of the cities they now considered to be run by anarchists. Democrats pled for mercy, painting the rebellion as non-violent civil disobedience. They either ignored its violent edge, or evoked boomer conspiracy theories that undercover Nazis and agent provocateurs drove the violence. The rebellion, antiseptically designated “civil unrest” by the media, was mostly peaceful, social-distanced, surgical-masked, and hand-sanitized, they argued.

Likewise, social movement activists expressed a common posture among young leftists with the chant: “Who keeps us safe? We keep us safe!” The objective of radical politics, they claim, is the creation of safety for all via the elimination of all forms of harm from society. This is a laudable long-term goal; avoiding unnecessary harm and danger is of course an important part of living in any community. The demand for safety is especially powerful when it comes from Black and Brown communities that have been made profoundly dangerous by enduring structural racism, including high rates of unemployment, state disinvestment, and other ingredients for violent interpersonal relations. But as the George Floyd uprising demonstrated, any conceivable path to a safer world will itself be quite dangerous. Who among the revelers of those riotous weeks could honestly say any of it was harmless or safe?

Behind the language of safety was a movement born in arson, defined by violent clashes with cops and widespread destruction of property, and driven by mass acts of risk-taking, leading to over two dozen deaths, over 17,000 arrests, and billions of dollars of damage. Above all, the rebellion defied Covid restrictions coast to coast. It would have been much safer — in the short term, at least — for the rebellion’s participants to stay at home and do nothing. Instead, they chose actions that exposed many people to considerable harm and put countless others in danger. This was not necessarily good or bad, but simply, in most cases, unavoidable. If one wished to distill not only the ethos of the late ‘60s, but the impulse that continues to guide those afflicted with immiseration, malaise, and rage today, perhaps a better slogan would be the Stooges’ mantra: Gimme Danger.

Homeland Security

The Stooges were part of a reverse white flight undertaken by poets, artists, proto-punks, and other bohemians. They fled the homogeneity of US suburbs that had exploded in the postwar period, subsidized by federal highway construction and federal loans. As Northern cities became Blacker and poorer, the chaos of deindustrialization and the deprivations of structural racism spurred a rash of violence in US cities, as well as a tremendous wave of rebellion. The suburbs became a zealously-guarded white bastion against the disorder of capitalism in decline, where working-class whites bound themselves to the rich in an alliance against everyone else. Television reinforced the schema by piping carefully-scripted fantasies of idyllic docility into the living rooms of millions of passive consumers.

It was an impossible fantasy world defended with belligerence. Under the obsessively pruned facades of suburban America lurked an ubiquitous violence against all threats to this ideal. As capitalist crisis, by no means confined to segregated urban spaces, menaced this precarious performance of affluence, consistently threatened to demote the self-proclaimed “middle class” into the ranks of the poor, centuries-long white fear of violent Black revolt, rooted in the repressed understanding that such bloody retribution would be justified, was stoked by images of Detroit, Newark, Watts, and other precursors to the George Floyd Rebellion. Caricatures of white youth joining Black revolts -- most recently, the reviled figure of “Antifa” -- was reproduced as the primary threat to the racial order on which precarious suburban life is built.

These twin fears of downward mobility and the vengeance of the vanquished are the guiding obsessions of life in the US suburbs: the eradication of danger or unpredictability of any kind. In the suburbs this took on the visceral form best represented in horror movies that popularize the fear of encroaching others in the form of the Haitian folkloric zombie, Indian burial ground-sprung poltergeists, or amoral outsiders of unknown provenance meting out brutal violence for no reason. Hysterical rumors proliferate of such dreaded others preparing to lay siege: Freedom Riders, Communists, M.S. 13, al Qaeda, Black Lives Matter. An endless stream of commodities -- security systems, background checks, home drug screenings -- monetizes the anxieties of people intent on denying the truism that life is temporary and safety is an illusion.

Seeded by the rotting cities, punk sprang as unruly weeds from white flight’s shitty soil. Its rejection of safety’s poison bait represented an urgency to immediately build and live an authentic form of life, no matter the risk.

The ultimate nightmare for the suburban subject was the 9/11 attacks. Simultaneously, it was a dream come true for authoritarians eager to redouble imperialist war abroad and the destruction of rights at home, all in the name of safety. The federal government instituted a color-coded warning system quantifying danger with no additional context, and it was treated with grave seriousness by many adults infantilized by the images of the toppling towers. While joking about 9/11 is today cliché, in those early days, when every vehicle, residence, and public space was expected to fly the US flag as a talisman against danger, in New York City it was only the punks who were brave enough to mock the jingoistic fervor.

The first were Lower East Side squatters Leftover Crack, creatures of Tompkins Square Park, a contested urban space where police have long repressed assemblies of radicals and houseless people in the name of public safety. Their debut LP, Mediocre Generica, was actually released on September 11th, 2001, but unlike Agnostic Front and the Strokes, who self-censored their records released that week calling for “dead yuppies” and mocking the NYPD, Leftover Crack was unapologetic about their own cop-hating and terroristic lyrics. The NYPD and FDNY aligned to ban Leftover Crack from playing shows by shutting down any venue that would host them. Three years later, the band doubled-down with a song called “Super Tuesday” on the album Fuck World Trade, celebrating the attacks and calling on its army of suburban punks to “tear apart these monuments to greed and build a new world from the broken pieces.”

Safety Punk

While punks were largely opposed to the war on terror and the security state, refusing imperialism abroad and tyranny at home in the name of safety, the war on Covid and its biosecurity measures have been relatively popular in punk circles. Punks preach tirelessly against the government, but at the pivotal moment when the capitalist state’s inadequacies were laid bare, their response was largely to publicly demand full compliance with public health authorities and self-police against any illegal assemblies, no matter how cautious. That the George Floyd rebellion was its own form of anti-lockdown protest has been denied and downplayed by punks in the same way as its militancy has been erased by liberals.

This “safety punk” praxis is part and parcel with the politics of incessantly scrutinizing and scolding people’s interpersonal behavior and consumption choices. While it is doubtless laudable to conduct oneself as thoughtfully and deliberately as possible in daily interactions, this kind of politics leaves powerless people castigating one another endlessly for perpetuating a system over which they have no real control, while no serious threat is posed to capitalism or the state.

This is not to say all the punks who took Covid seriously are safety punks. Without articulating an anti-lockdown politics, many punks, anarchists, and other traditionally danger-attracted political subcultures stared the virus in the face to test the vagaries of early COVID-restrictions. They set up mutual aid networks, organized rent strikes, and fought police in chaotic melees at the frontlines of the demonstrations. In those first months of lockdown it was assumed that everything from handing out bags of groceries to the public, engaging the police, going to jail, or assembling with one’s neighbors, however masked, were likely routes to a potentially deadly infection. It was at least late June before we figured out for sure that outdoor demonstrations did not constitute “super spreader events,” as many politicians and pundits were arguing to discredit the rebellion. We gathered nonetheless, deeming this risk worthwhile.

Despite their courage and effective rejection of the neoliberal lockdown in the US, this punk faction of mutual aid and anti-state rebellion never explicitly framed itself as rejecting Covid protocol. The result is that punks and the left in general have drifted in the popular imagination farther away from oppositional culture, often appearing more like eager hall monitors of the biosecurity state. Meanwhile, the spectrum of right-wing Covid skeptics captured a nebulous anti-authoritarianism of the masses towards medical and scientific institutions, politicians, and international corporations and NGOs, as part of a powerful, often armed, movement against the lockdown that has served as the basis for a renewed tradition of revolutionary rightism, as seen on the January 6th attack on the Capitol. And this triumph of right-wing populism in leading challenges to the lockdown would soon find its own analogue in the world of punk.

Hardcore Summer

By April, 2021, more than half of the adults in New York City had received at least one of their vaccinations, and the science showed what uprising participants already knew: wearing masks outside is largely unnecessary. Thanks to reaction against Donald Trump and the US far-right, however, basic Covid safety protocol remained a theater of the culture war; masks assuming the role of powerful symbols independent of their function. A remark overheard in Washington, D.C. in late April captured this predicament: “I guess I'm vaccinated so I don't have to wear a mask outside but … I really don't want people to think I'm a Republican.”

Meanwhile, youth with no discernible connection to punk rock or leftism were organizing public parties, flash mobs, and secret raves to celebrate the end of the lockdown that everyone in left circles knew had come but, fearing the wrath of Twitter Karen mobs, few would publicly admit. The New York hardcore (NYHC) scene was the perfect vehicle for breaking this stalemate. “In your eyes,” Freddy “Madball” Cricien once sang, “we’ve always been the bad guys.”

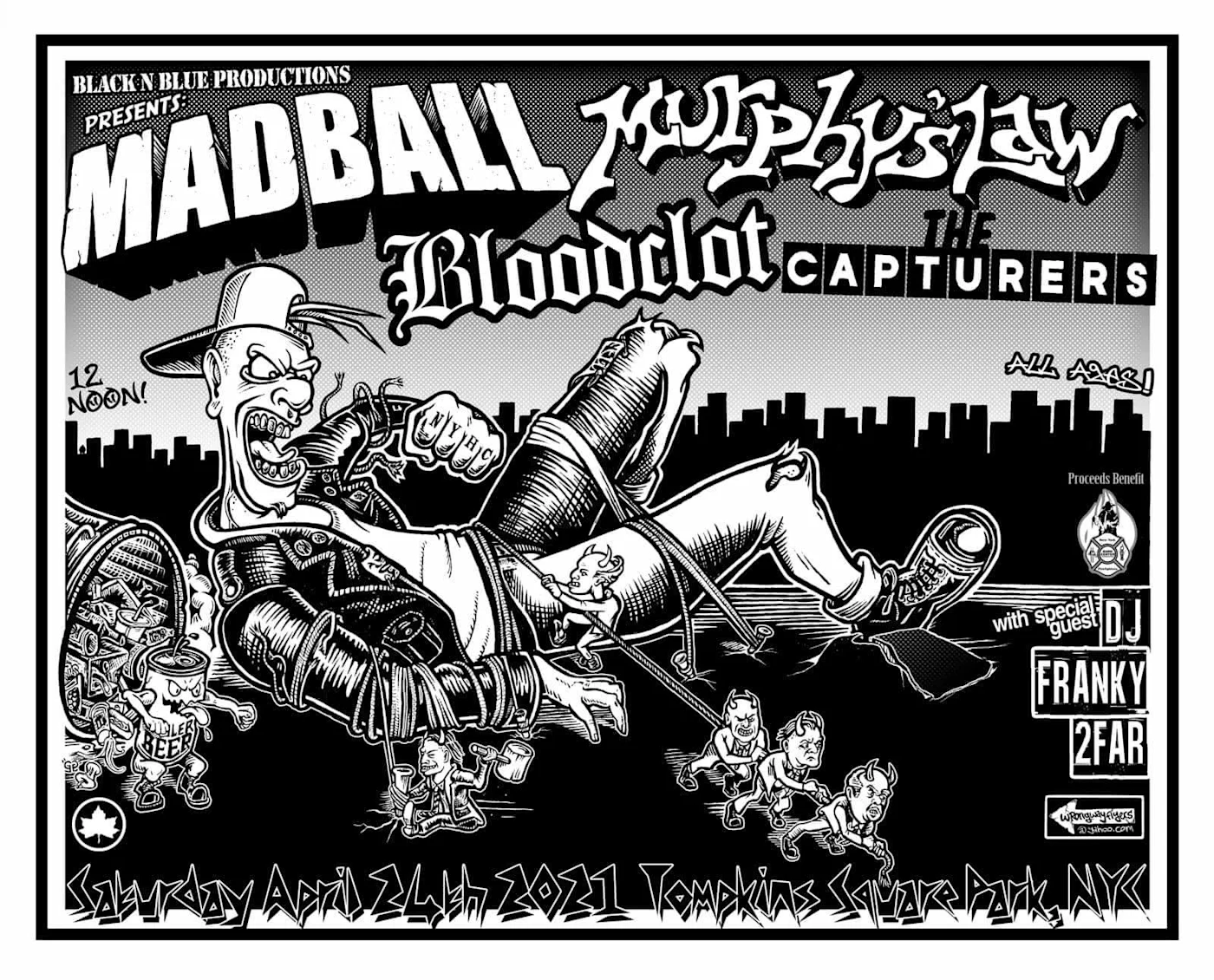

On April 24th, Black N’ Blue (BNB) Productions hosted a massive hardcore punk show at Tompkins Square Park featuring Madball, Murphy’s Law, Bloodclot, and others.. The flyer depicted an iconic NYHC cartoon mosher breaking free, a la Gulliver’s Travels, from hordes of horned demons in business suits staking him down. The message was clear: Lockdown is over! Thousands of hardcore fans poured in from across the country for a big party in the Manhattan park best associated with rebellious use of public space since the 19th century. Despite the gathering of roughnecks from all over the US, there were no fights and nobody was seriously hurt, even with a number of acrobatic stage dives into a massive mosh pit on concrete. But those sitting at home had other thoughts; photos and videos of the show quickly spread across the Internet, where it raised a collective wail from safety punks on social media -- though no one could agree on exactly why.

In a denunciation of the show penned for the Onion AV Club, music journalist Tatiana Tenreyro evoked a staple of safety culture: stranger danger. “In case people still need the reminder,” Tenreyro wrote, “while the vaccine rollout is gaining speed in New York City and the CDC says masks don’t have to be worn outside anymore if you’re vaccinated and hanging out with fellow vaxxed people, it’s still not safe to be in crowds with strangers!” In one swoop, Tenreyro conceded that the show’s detractors didn’t have much scientific basis, but nonetheless insisted it was “a serious health hazard,” without elaboration.

Another line of attack picked up on the veracity of the show’s permit, a sudden topic of concern for these so-called fans of punk rock. Gothamist reported that the BNB, in collaboration with the wingnut anarchist publication The Shadow, had fraudulently claimed the show to be a 9/11 memorial of an anticipated 100 attendees. While BNB was likely sincere in their desire to support the New York Firefighters Burn Center Foundation, the pretense was at least partially sought a loophole by exploiting the residual 9/11 jingoism of New York’s political establishment. In effect, they mocked the police -- culminating with Madball’s line from “Smell the Bacon”: You’ve got your badge and you’ve got your gun / Don’t shoot us down because we’re just having fun.

Above all, these detractors were assisted greatly by the organizers and some of the band members themselves. The social media for BNB, along with pages run by Bloodclot and former Cro-Mags vocalist John Joseph, had become a cesspool of anti-vaccination conspiracy theories. At Tompkins, BNB organizer hawked quack Covid remedies between bands, alternatively insinuating the pandemic was a fraud before calling for a moment of silence for the lives it had claimed. David “Springa” Spring of the band SSD, whose foolish drunken behavior has made him the butt of hardcore in-jokes for decades, appeared on stage wearing an idiotic homemade shirt that read “Black Flag Matters.” Later, evoking the rebellion itself in unfavorable terms, John Joseph complained: “For the last year in New York City there were protests - tens and thousands of people in the streets - some rioting and looting engaging in bias attacks [???] - nobody said shit - the media condoned it.” When he declared the show was an anti-lockdown rally, no one really disagreed.

By this point it didn’t matter that the organizers had set up a Black Lives Matter table at the show, or that Black and Latino people were numerous in the audience and bands -- as they always have in New York Hardcore. Social media had found its villains of the day.

The NYHC luminaries who had performed songs for decades celebrating their status as shunned outsiders in the crime-ridden streets of lower Manhattan stepped into this role with uncontained glee. John Joseph released multiple statements, as BNB obsessively updated its social media pages denouncing fake news and faker punks. Both sides -- NYHC old heads and the latter-day safety punks -- got high on their own righteous anger for days on end. Meanwhile, nobody associated with left politics risked the label of culture war traitor to defend the show. Instead, most bands and organizers continued to wait for an opportunity that was, in a political sense, safer.

Two weeks later, punks in Los Angeles staged a massive outdoor show of their own. Foregoing permits, they packed up to 2,000 people in a graffitied concrete basin underneath the 110 Freeway for a show featuring N8NOFACE, Section H8, and others. Videos show the massive crowd moshing, fire breathing, and setting off fireworks around a bonfire to the sounds of beatdown hardcore. The LAPD issued a citywide tactical alert and attempted to disperse the crowd by flying a helicopter low above the pit. When the punks only moshed harder, the cops resorted to rubber bullets.

It was the stuff of punk rock fantasy; one of the musicians said that playing the show was like stepping onto the set of The Warriors or The Lost Boys. While it was by no means safe, apparently nobody was seriously hurt. Surreal images quickly spread across the internet, earning effusive praise -- and none of the blowback seen in New York, though only two weeks had passed. Punk rock pundit James Khubiar, who had denounced the Madball show in a lengthy social media rant about Covid safety, responded with one word: “Incredible.” The trail had been blazed in New York by a bunch of meatheads who didn’t care what anyone had to say about them. After LA, punk show promoters had a green light to bring back the music.

See You in the Pit

The end of the lockdown has revealed one of the lingering effects of the George Floyd Rebellion to be a more belligerent conception of how public space can be used. This is one of the cultural fronts on which rebellion will continue until we are back to the barricades.

Yet in today’s socially-conscious subcultural scenes, a few loud people make the rules and most people just follow along, hoping to avoid being called out and subjected to torturous public humiliation. The Tompkins show was evidence that lots of people wanted shows back, but were waiting for someone else to take the lead. The punk fans who descended on Tompkins Square park had waited for over a year until the risk of Covid had been mitigated. Unlike safety punks, they were likely aware that much like the Spanish Flu, which is still with us today, Covid will never go away completely. Danger, after all, can only be negotiated, never eliminated altogether. It is our constant companion, whether in politics, music, or just walking down the street. This is true of the radical transformation of society through insurrection, that will be necessary to build a society where everyone’s lives matter. It also applies to the daily practices of shared illegality and risk-taking that will build the ties we need to smash capitalism once and and for all.

In hindsight, NYHC was an imperfect yet suitable vehicle for leading punk out of a lockdown that only sought to ban leisure and police interpersonal relations, while leaving the capitalist economy, the actual source of the virus’ proliferation, unchallenged. Hardcore reaffirmed its historical role as punk rock’s ignorant id, busting through its self-satirical, avant-guard facade with all the subtlety of a CBGBs mosh pit. For NYHC, punk is not fashion, not “inessential,” but a way of life, a weapon in a daily struggle for survival on the mean streets they have always loved. NYHC is a brutish, pre-political populism that could break right as easily as left, but it speaks to the anti-establishment core of blue collar America that will never be as safe and sanitized as left purists want it to be. Taking back the streets from fear and quiescence, in Tompkins Square of all places, was a powerful gesture, no matter the ignorance of some of its loudest voices.

And why should this mantle belong only to reactionaries pedaling anti-vax conspiracy theories and politics representing the worst aspects of American anti-statism? In our uncertain period of “reopening,” not just punks, but artists, activists, and revolutionaries in general have a unique opportunity to fill the cultural void with conflictual, transgressive, and otherwise risky situations. For the most part, these scenes have been orchestrated by teens in Washington Square Park, Spring Breakers, Tik-Tokkers, sideshow drivers, dirtbikers, and ravers, who are bringing the spirit of the George Floyd Rebellion to fresh contests over the question of who owns public space.

Punk need not be a necessary component of this countercultural reemergence. But for those of us who still have some affinity for it, it was sad to see only various stripes of conspiracy theorists like John Joseph organizing public shows, while everyone else cowers in fear of social media pundits whose stock and trade is outrage and condemnation. While punks may never make good on their calls to “kill cops,” we can at least start with the ones in our heads.