Illness in or as Economy

Sasha Warren

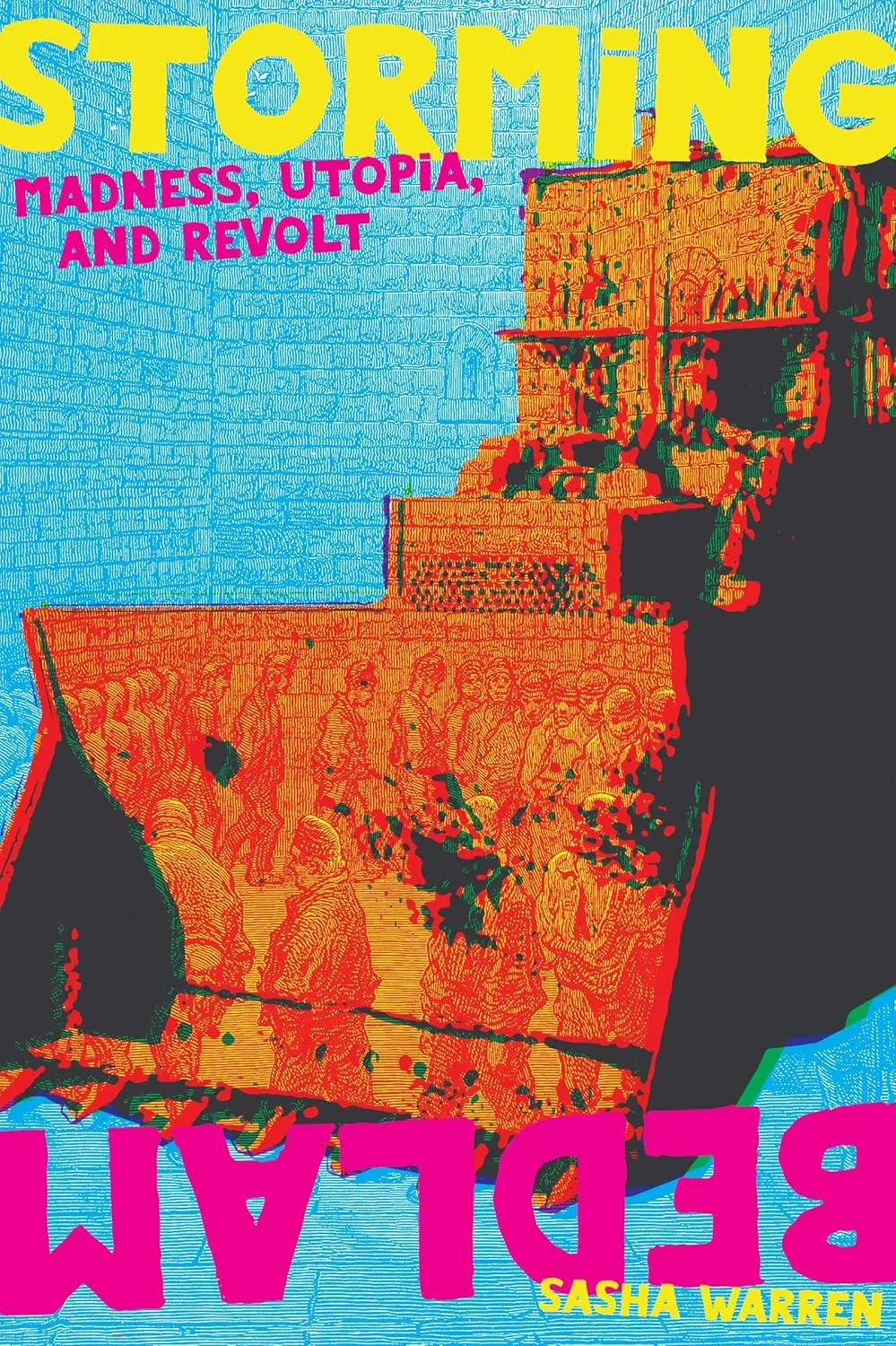

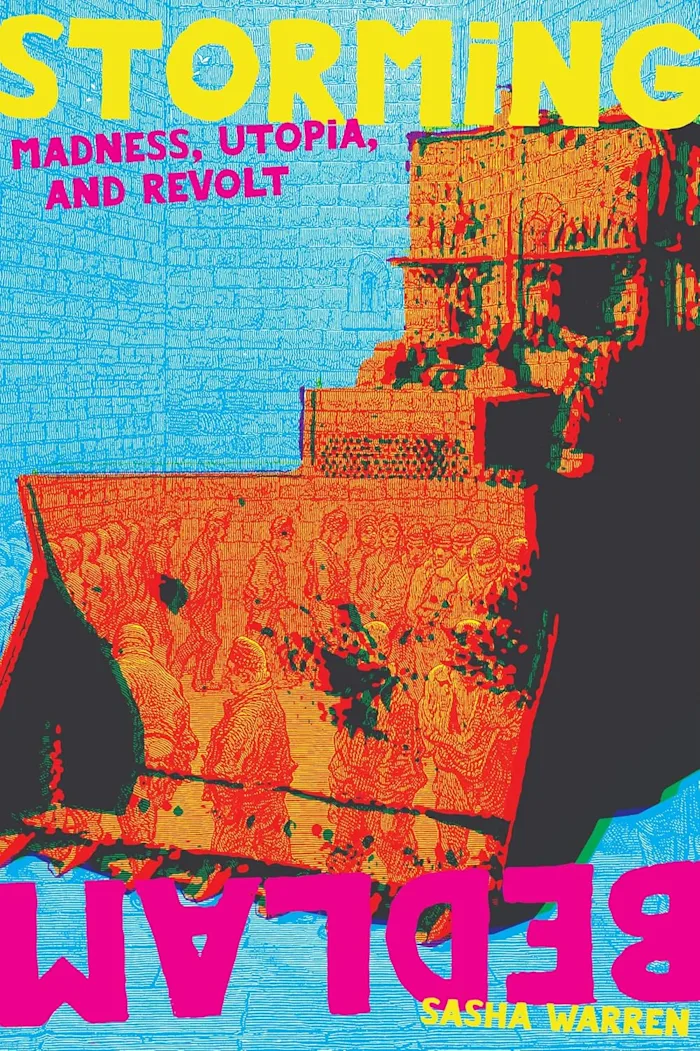

“Illness in or as Economy” is an excerpt from Sasha Warren’s new book Storming Bedlam: Madness, Utopia, and Revolt, released by Common Notions in March of this year. In it, the author provides a critical analysis of the SPK, or Socialist Patients’ Collective, a radical experiment in patient-led materialist psychiatry founded in Heidelberg, West Germany in 1970. While some readers may already be familiar with the history and influence of SPK, Warren focuses on the group’s unique conception of the relation between illness, psychiatric / medical power, and political economy, which led to a “reconceptualization of political and personal identity.” In a moment in which friends and foes alike readily define our world as sick or ill, or insist that we ourselves are sick or ill because of the world, Warren’s attention to SPK’s analysis of “illness” and its source can be of use to those searching outside of the causality of diagnostics. In line with the broader aims of the book, which aims to give an account of radical experimentation in psychiatry across the 20th century, Warren’s analysis of SPK provides a venue to think through the political potential of understanding our estranged conditions without losing sight of the specificity of illness’ sufferings.

Other languages: Español

Young people growing up in Germany in the 1960s and ’70s were confronted with the reality that many of the parents, grandparents, schoolteachers, nurses, and psychiatrists who willingly participated in euthanasia programs or concentration camps (or blissfully ignored them) managed to secure cushy university or hospital positions. In the late 1960s, facing an economic crisis, the coalition parliament formed an emergency government that nullified the parliament. To the growing German left and student movements, the fear that the West German government could slip back into its fascist mode in a crisis was seemingly confirmed when, in response to large protests against a visit by the shah of Iran to Berlin in June 1967, the state’s security forces implemented far-reaching emergency orders banning demonstrations, shutting down highways, and sending in thousands of police. The murder of student protestor Benno Ohnesorg exacerbated the crisis into a fever pitch.1 1968 represents both the climax of the collective rage of the student movement and the beginning of its disaggregation: soon after, it splintered into numerous Maoist and Marxist-Leninist cadres, autonomists and Spontis, feminists and antinuclear activists, squatters and queers, and, of course, the big bads, urban armed-struggle groups.2 All this coincided with the rediscovery of Wilhelm Reich’s work and the translation of critical and antipsychiatry texts by David Cooper, R.D. Laing, Franco Basaglia, and Félix Guattari around the same time, bringing with them a new lexicon of desire and an emphasis on psychopolitics.3

Amid generational clashes, new youth movements, and the growth of antipsychiatry, there emerged in Heidelberg, a city in southwest Germany, what Jean-Paul Sartre called “the only possible radicalization of the antipsychiatry movement”: the Socialist Patients’ Collective [das Sozialistische Patientenkollektiv], or SPK. The continuous hostility of local media and a healthy dose of self-mythologization have led to factual disputes that shroud their development through the 1970s in murkiness and fog. What is certain is that the group began organizing actions around 1970 out of the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Heidelberg.

Heidelberg’s psychiatry department offers a microcosm of Germany’s psychiatric legacy: it was the workplace of one of the most important psychiatrists of all time, Emil Kraepelin, whose classificatory system serves as a prototype for modern taxonomies; it was and is home to the Prinzhorn Collection, one of the earliest and largest collections of patient artwork, which has preserved works for over a century; and, during the Nazi years, under Carl Schneider’s directorship, the staff helped organize euthanasia killings. In 1955, the university made a gesture towards a new direction by hiring Walter von Baeyer, a Jewish professor with a progressive agenda. Influenced by the social psychiatry currents in Britain and the US, he decried the still wretched conditions of Germany’s mental hospitals, advocated for community care and psychotherapy over custodialism and aggressive physical treatments, and talked positively of radical psychiatrists like R. D. Laing and Franco Basaglia. At the same time, the university kept multiple nurses and psychiatrists who served in the SS and were involved in the Nazi euthanasia program4, a situation which led to a split between a more traditional psychiatric milieu and the social psychiatric one. The SPK represents the extreme limit of this split. They first began to take shape around Wolfgang Huber, an intense and prickly assistant in the Psychiatric and Neurological University Clinic hired in 1964. Between 1964 and 1969, Huber started to skip conferences and meetings while simultaneously extending his meeting hours late into the night to avoid supervision before frequent clashes with colleagues resulted in having him moved to the undesirable polyclinic in 1969 where acute patients were observed, sorted, and likely moved elsewhere after a brief time.5 Despite the barriers, he began to amass a number of supporters who organized large therapy sessions that more closely resembled political rallies than conventional group therapy meetings. These became unmanageable and thus a target for the administration around 1970, who feared that this man was so lost in his work he “might prescribe dynamite!”6

Things came to a head on February 5, 1970, when the university finally tried to evict Huber and about sixty patients. But the patients refused to leave. Instead, they called a general assembly in the clinic and hunkered down for an occupation. This continued until February 29th, when they struck a compromise with the university, never fulfilled, which promised the patients the renovation and use of a work room and a lump sum payment for development. Out of frustration, in July the SPK occupied the Rector’s office and increased the scope of their demands: they wanted patient control over all care, over right to residency, over the clinics’ funds, and over a house to use as a crisis or refuge house. Though they attained official recognition on July 9th, 1970, they were repeatedly attacked in the media and by the university in public statements until they were formally evicted on November 14, 1970, which was not effectively acted upon until a second order was given in May 1971. After being evicted, many SPK members were arrested in late June on suspicion of being involved in a shootout with police. Throughout this period, their primary collective activity consisted of what they called “agitations,” as opposed to therapy, the main point of which was to identify individual needs and both denaturalize them — situating them in a historical context — and collectivize them. On top of that, they collected a few Deutsche Mark at every meeting to allow poorer members to participate in basic care functions: they offered free childcare for those who needed to work; performed home visits to diffuse tension between partners and roommates or to help solve crises; tutored students who were falling behind; secured medications without the mediation of the clinic when possible; and helped to work out labor or housing disputes by pressuring bosses and landlords.

In terms of their activity and material demands, the SPK were militant and impressive but not so different from similar groups around the world that demanded patient control and offered alternative support structures. Their uniqueness lies rather in their conceptualization of psychiatric/medical power and illness in relation to the economy and the reconceptualization of political and personal identity this brings about. There is much confusion around what the SPK actually wrote, due in part to their own proclivity for falsifiable hyperbole and crude sloganeering.7 The notion that mental illness is socially determined is often attributed to them, but this is actually disputed on the very first page of their primary text, Turn Illness into a Weapon, on the concept of illness:

[I]t was clear to us from the outset that it’s completely unsatisfactory to look for a single bodily cause according to the model of scientific medicine. It also quickly became clear to us that it’s not enough simply to speak of the social cause of illness, that it’s too simple to pin “responsibility” for illness and suffering on “evil capitalism.” And it became clear to us that it’s a completely abstract and ineffective affirmation simply to say that society is ill.8

They hold that illness is not reducible to the purely biological, but it does not follow, as it is often said, that it is socially determined; outside of these two dominant narratives, what are we left with? Notice that the SPK does not speak here of mental illness, madness, nor disability. Instead, they use the generic term “illness.” Why? One must contextualize their reclamation of illness within the more common refrain that mental illness is not a disease like any other because it lacks a localized cellular or molecular lesion or because of its legal ramifications. Illness, for the SPK, is not a thing nor a state, but it is, nonetheless, very real and a constituent part of contemporary capitalist society. Illness is the crux of their argument and works on multiple levels at once, both abstract and empirical, general and highly specific, and it bears an essential relationship with capitalism: “Illness is the essential condition, the presupposition and the result of [the] capitalist process of production.”9 This is not the same as saying capitalism alone causes illness or illness didn’t exist until capitalism, but it is to deny a “natural, objective” illness existing free of material context.

Early on in Turn Illness into a Weapon, they make it clear that illness can be understood as alienation, in the terms set out by Marx: it “is the alienation [Entfremdung]” as it is experienced “subjectively, as the experienced condition of physical and psychological needs of the individual.”10 In the capitalist mode of production, the worker is estranged [entfremdet] and alienated [entäussert] from their activity. In The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts, Marx explains what this means: first, he says, because labor is not freely chosen, but is taken up as a forced necessity for survival, it exists outside of the worker. Though they make the world, the worker is denied the capacity to freely choose their mental or physical activity. Therefore, the more they work and produce, the more alienated they are from themselves and from the things they create, the less time they have to undertake their own endeavors and develop themselves — the more their “own time” is reduced to mere reproduction (eating, sleeping, drinking). The type and intensity of work does not arise from one’s own desire or capacity, but from the necessity of survival, which means that working beyond one’s own physical or mental limits or in terrible conditions is, for most, an inevitability. Work is experienced as organized mortification and denial, an exhausting expenditure for products that oppose the worker as an inaccessible and alien world of things fulfilling none of their immediate needs.11 The world is so arranged that, in pursuance of the means of survival, one must alienate oneself from one’s own power of production and sell it off to another, eventually resulting in physical or mental degradation, as Marx argues in Capital, Vol. 3:

[A] certain crippling of the body and mind is inseparable from the division of labor in society as a whole. But since the age of manufacturing pushes this separation of kinds of work much further, and in its way of dividing the individual attacks him at the roots of life, it is the first age to supply the material and the start to industrial pathology.12

Illness can be understood in this multifaceted sense of alienation / estrangement from the product of labor, from one’s own capacity to produce, which in turn presents this alienated world as a natural one. For the SPK, that mortification of the self from the world whereby one “becomes merely a fragment of [one’s] own body” is illness, something which becomes particularly apparent in those cases when this persistent, endemic mortification is subjectively experienced as pain and destruction, e.g., in the form of workplace injury, psychic crisis, or immiseration.13 Capital sets one part of us out against another. Illness describes the “damaged life, life that contradicts itself” that lives through such an experience.14

We may seem quite far from the question of madness or psychiatry at this point. Indeed, part of the SPK’s strategy is to despychiatrize madness and present it as a specific type of the alienation process inherent to capitalism. But there is also a historical precedent for their organization in that psychiatry initially confronts madness as “alienation” and ties it to the question of civilization and industry. This brings us back prior to the totalizing medicalization of madness, when what we would call “psychotic” types were conceived of in terms of delirium, or forms of alienation from reason. The mad person has a privileged position in this schema, in that they confront society either as the alienated who have lost contact with civil society and need a shepherd to guide them back or as aliens who are so far gone as to appear as animals. The SPK reverse the terms: to be ill/alienated is actually to wield the potential of increased consciousness of the estrangement of the world. To be healthy is not at all possible; those who believe they are healthy are unaware of their real estrangement from the world. The healthy ideal only describes readiness for exploitation and further mortification, which is itself a state of illness.15

To better explain this, the SPK divides illness into two possible elements: the progressive element [das Moment] and the reactionary element. Take the example of paranoid delusion discussed in the book. In the common representation, the paranoid person feels themself beset by unknown forces (voices, visions, or mysterious figures) that assault them as an omnipresent force, as if from the environment itself. This differs only in the specifics from the explication of alienation recounted above, and, indeed, “delusion,” the SPK say, “is the product of the individual’s objectification in capitalist society, it’s the expression of the polarized relationship of life and capital, of organic and living matter with inorganic, dead matter.”16 Paranoia as a totalizing sense of estrangement from the world that antagonizes the individual as an alien force expresses the truth of the world. Let’s say the paranoid feels followed or surrounded by murderers and holes up in their apartment to escape the horrors outside. Another truth is barely under the surface: murder is the norm of the capitalist mode of production, both immediately in the form of domestic police executions and clearing the way for imperial accumulation, and over time with avoidable accidents or exposure to viruses and diseases at the workplace. Even so, illness having a basis in social reality does not determine its outcome and expression; it is merely a starting point. Normally, the patient’s illness is objectified as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, freezing it as a manipulable and stigmatized property of a person, or, at times, even supplanting the person as their primary form of identification. One’s adaptive condition of living is seized, frozen, turned inward, made into the central property, the primary condition, of the individual while bizarrely remaining outside of them at a remote distance as the discrete cause of increasing magnitudes of guilt, fear, and confusion. In its reactionary moment, that which connects us to the social world is repressed and illness is experienced as a limitation, an “inner prison” belonging to us, in a way, but experienced as if we belong to it.17

The only real right one can count on in a capitalist society is the right to sell labor power; when one is perceived to be incapable of doing so due to being depleted by or excluded from the market, they are no longer the bearer of rights and face the law nakedly, as a “human wreck” or a waste product.18 Healthcare is organized so as to either maintain the exploitability of the ill or at least to contain and manage illness in its repressed form by molding them into patients dependent on the most profitable, and not necessarily the most effective, medical techniques and medications.19 “Hospitals are places of production in the same way that factories are,” one member said in 1970, “the patient must turn in everything he has produced there: stool, blood, urine, bile…headaches, hallucinations… These products translate to medical bills, lab bills, administrative costs…thus the illness flows back into the state treasury.”20 The SPK write:

Illness is collectively produced: that is, insofar as the worker creates capital in the work process, which encounters him as an alien force, he collectively produces his own isolation. It’s therefore only logical that healthcare produced by capitalism perpetuates this isolation in that it doesn’t treat these symptoms as collective but rather treats them as individual bad luck, fault, and failure. However, capitalism produces, in the form of illness, the most dangerous threat to itself. Therefore it has to fight against the progressive moment in illness with its heaviest weapons: the healthcare system, the legal system, the police.21

Illness is Janus-faced, that is, it looks forwards and backwards; it is potentially both a beginning and an end, process and product. These passages speak to the surreality of the last few years when: more than 6,000,000 people are dead from COVID-19, so many of whom were forced to work in positions that put them at high risk of contracting the virus or were living in nursing homes or other facilities designed to manage the ill, old, and debilitated, along with the prisons and hospitals; schools are expected to stay open so parents can go to work, no matter the risk; in the midst of slow catastrophe, pharmaceutical companies were allowed to privatize vaccines and withhold them from poorer countries, even though this is tantamount to murder. Our bodily and mental integrity is being held hostage by the very system that makes the world work. We live in the fever dream of humanity, in a giant unreality of our own making trampling on us every day. States rationalize eugenic measures about who is worth sacrificing in the name of the market; all we get in return for integrating our bodies into this machine is the bare minimum of care necessary to preserve the flow of commodities. In more extreme crises, when the sick surplus cannot be maintained at low costs or adjusted forcibly to a norm, they are simply dispensed with in slums or institutions, one way or another, by slow exposure to deadly conditions or rapid liquidation. Our unreality is produced, our disunity is remade daily in the linkages that make things we need and keep things moving, all united and organized under the sign of general accumulation in a dream world traveling along a fateful path where there are no real accidents: we can reasonably expect a thousand water crises, cascading extinctions, cancer epidemics, and widespread famines in the coming years.

We live in a big open pit mine; its poison seeps into our blood at different speeds, but it is in everyone. There is no discrete suicide epidemic here or there; we are all in a massive suicide cult inching towards an ignominious mass death of humanity. Located in the polyclinic, the function of which was to observe, sort, and ship mental patients to their next destination at the very same university where they once sent them off to be murdered, the SPK were uniquely well-situated to make such observations.22

Turn Illness into a Weapon can be read as the search for a counter-universal capable of organizing medicine under the sign of process relations and material conditions in a form that confronts the National Socialist concept of illness as a racial universal with the utmost force. They certainly weren’t alone. As the war came to an end, Ana Antić writes, “a different and genuinely global psychiatry” was called for “to alleviate the cataclysmic effects of pathologies and prevent the suicide of humanity.”23 Global health agencies like WHO, UNESCO, and WFMH were called upon to produce research and theories that united humanity rather than divided it, setting in motion a hunt for universals. Theories of universal development, which we encountered in the last chapter, inscribed alterity more creatively by equating “primitive” humanity and the mad with the figure of the child, which is excluded from civic participation. Other “transcultural” approaches assumed that their categories of schizophrenia or depression were the “real” ones and only sought to find how other cultures defined them.24 More subtle (though not necessarily actually “universal”) theories were also in circulation in the colonial world: Wulf Sachs’ Black Hamlet sought out the patterns and constructions that underlie and constitute mental life for everyone without implying the universality of any diagnostic constructs, but even this humanist effort struggled to retain a balance between political and cultural determinism that didn’t reek of a colonial attitude. The decolonizing world was not short on proposals for humanist, cross-cultural psychiatry that took up the mantle of the universal mind as a clarion call against Eurocentric ones that only subtly reimagined the superiority of the white Western mind.25

A middle position between the humanist universalist one and the SPK’s are the contemporary critiques of neoliberalism and the Global Mental Health movement that view psychiatry as a tool for molding psychiatric subjectivity by subtly coaxing wounded individuals — stressed out and anxious from the instability of the economy or the climate — into medical consumerism under the guise of treatment.26 From this angle, one of the main drivers of psychiatric theory and practice is the consumer market, specifically the market in psychiatric drugs since the rise of psychopharmacology in the 1950s with the introduction of the antipsychotic Thorazine. In this view, psychiatric diagnoses are forms of subjectivity essentially wedded to the flux and growth of the drug market, which ties the rapid proliferation of new diagnoses (each with a variable assortment of potential drug regimens) to the neoliberal notion that certain market decisions can shape one’s identity and solve (or mitigate) personal crises and traumas. Here, the consumption of psychiatric drugs necessitates a prior, more significant, transformation into a dependent self that requires the drug for reproduction, a self that ties its notion of wholeness or presence to a compound that can actualize it.

Drugs have come to play such a central role in psychiatry that they sometimes appear to be the central question of both the practice and its critique. This singular focus can be perplexing from the outside, for drugs are just drugs. Like alcohol or heroin, Lamictal and Olanzapine are, in the end, mere chemical compounds, inert in themselves with neither benevolent nor evil properties. Putting aside all attendant controversies over efficacy and danger, it is easy to see that the reason drugs elicit such an extreme response is that they, too, facilitate ways of being human in relation to other humans. Indeed, the dispensation of drugs may be the largest or at least fastest-growing way in which mental illness as an identity has been mediated in the United States since the mid-twentieth century, and now globally. Drugs ask things of the individual who ingests them, or they act as facilitators for questions asked by another. Their effects, good or bad, beg the question: who or what is being acted upon, corrected or corrupted when I take this thing and feel different? With psychiatric medication, one is asked to swallow and digest, not just a drug with this or that material effect, but an identity altered, managed, stabilized, or even only actualized on account of a chemical solution. Unsurprisingly, drugs are a productive and always contentious turning point in the recalibration of mad subjectivity, actualized through tapering, experimentation with psychedelics or other nonpsychiatric drugs, or a purely instrumental usage that strips them of deeper pretensions. This demonstrates above all that the way we take drugs changes the experience of them entirely. I drink alcohol regularly, and, like any drinker, I know that having a drink alone after work is an entirely different experience than taking it in the company of friends on the weekend. In the Spinozist sense, we can say that drugs are a body that either agrees or disagrees with mine under certain conditions. But that’s too easy. A large part of why it agrees or disagrees has to do with the way it’s dispensed. An antipsychotic taken voluntarily in full awareness of its limitations, its side effects, and its instrumental (rather than ontological) uses for the explicit goal of making social life more fruitful is a different drug than the very same antipsychotic ingested due to a court order shrouded in mystifications like “it helps your brain work better” in service of calming one down. Drugs are about who we are and how we become who we are in the company of others, but the pro- and anti-drug literature does not reflect that in the back and forth about whether they are good or bad in themselves.

The critique of neoliberalism and psychiatry appears especially persuasive when one takes note of the way psychiatric language has so thoroughly permeated the broader public’s way of discussing everyday problems, thanks in part to the ubiquity of anti-stigma campaigns on bus stops and football commercials, the unbridled bloating of diagnostic manuals heavy enough with ailments to be used as weapons, the drug industry’s bold advances into the unconquered territories of youth and banal deviations, and the shift in mental patient status from being overwhelmingly involuntary to largely voluntary. In other words, there has been a rise in a participatory, common psychiatrization of increasingly microscopic deviations that would, in times past, not have come onto the radar of psychiatrists except for the wealthiest patients. Psychiatric imperialism reigns supreme and not just in the most developed economies: Ethan Watters27 and China Mills28 have written about the voracious advance of psychiatric diagnostic categories exported and introduced into markets in the Global South, often with funding and advertising by pharmaceutical companies without concern for local exigencies or traditions of diagnosis and healing. These are new processes, but they are dramatic: the market in psychiatric medications is expected to become a $40 billion industry by 2025 (nearly double its current size) in response to the expected rise in patients due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

But it’s hard to see how these could be determining factors for the field prior to the end of the twentieth century: throughout most of its history, most psychiatric hospitalizations were involuntary, and, even when this started to shift in the 1960s, voluntary hospitalization remained at around 20 percent until just the last few decades. In the past, most people who became regular users of psychopharmaceuticals did so following the experience of being hospitalized. It wasn’t until the late 1990s that the FDA moved to allow drug companies to market directly to consumers with ads that encourage people to go to their doctors and ask to receive specific diagnoses and medications.

Complicating this further is the fact recounted by Liat Ben-Moshe that — contrary to the idea that psychopharmaceuticals were the turning point from institutional psychiatry to a diffuse, capillary mode catering to private consumers — Thorazine was originally marketed to skeptical psychiatrists as a managerial tool to keep the ever-growing morass of human beings in overcrowded asylums a half-sleeping collectivity.29 While plenty of people are making a good deal of money off of psychiatric research and treatment, particularly in the largely unregulated private facilities in the United States and the introduction of a new drug market in countries without substantial psychiatric infrastructure outside of the major cities, the profit motive cannot be the sole nor even dominant driver of change and adaptation in psychiatry, nor would it explain its origins or major shifts prior to the growth of the pharmaceutical market. As far as training goes on an individual level, while entering the field may provide the psychiatrist with a comfortable salary and plenty of opportunities to exploit prospective patients, there are manifold simpler and more economical ways to ensnare and fraud a consumer base in twenty-first-century capitalism. Becoming a stock trader, an alternative health guru, or a snake-oil salesman doesn’t require years of postdoc residency training. In this light, the idea of psychiatrists getting into the field because they have conscious aspirations to be social engineers and control their patients through medications is equally untenable when one could become a police officer with far less training and schooling, even less oversight, and no requirement to pretend to do anything besides guarantee the status quo by means of force. That’s not to say that psychiatrists aren’t today motivated by the prospect of making money or that they don’t enjoy leveraging power over patients, but that these are not likely the central enticements of the work for most, and thus exist in tension with whatever intentions individuals bring to it. Nor is drug market expansion sufficient for explaining the rapid growth of global psychiatry’s client base. Psychiatry is a historically contingent phenomenon tied up with the spread of market relations, the complexities of urban life, and the destruction of traditional means of mitigating stress and absorbing difference. Drug companies certainly have a vested interest in inserting themselves as the simplest solution in vast untouched reservoirs of human misery. Lacking other cheap and easily applicable means of attenuating the speed and violence of this destruction, it is not hard to imagine why psychiatry and its tools would be in demand by states rushing headlong into exponential growth seeking to manage the excessive suffering of humanity left in its wake.

Health and illness as we encounter them on the pages of Turn Illness into a Weapon are fundamentally unlike other universals, for what unites humanity here is no longer a constitutional design nor a series of innate patterns, but our common condition under capital. For the SPK, these theorists may believe they are inching ever closer to the innate reality of brain and mind, but they don’t theorize the fact that all reality we encounter is transformed by the conditions under which it is produced. As damaged life, illness confronts not just consumption but capitalist production and circulation as an absolute limit: if too many bodies are ruined beyond repair, the work stops; if illness completely permeates the social world, nothing moves without enormous risk. The bodies and minds of a sufficient quantity of workers must be sustained to the degree that enough of them can get up and work again the next day; the working day is limited in part by the hours of the day, in part by the reproducibility of laborers. This is the fulcrum of the revolutionary potential of illness and where the possibility of the “progressive” element presents itself, when “fear will turn into a weapon.” Illness, insofar as it is an expression of the real contradictions that permeate our social world, contains within it the seeds of a form of protest, a potential rejection of one’s conditions and the expression of the need for transformation. At that point, one can manage it, repress its call, or “turn illness into a weapon.”30 At its base, the SPK offer a variation of the Marxist theme of immiseration: capitalism, said Marx, “far more than any other mode of production is a waster of people, of living-work, a waster not only of flesh and blood but also of nerves and brain.”31 Sartre was spot on when he quoted Friedrich Engels’ 1845 Condition of the Working Class in England in his preface to Turn Illness into a Weapon, for the theory of illness under capitalism stays close to his theory of “social murder”:

When one individual inflicts bodily injury upon another, such injury that death results, we call the deed manslaughter; when the assailant knew in advance that the injury would be fatal, we call his deed murder. But when society places hundreds of proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and an unnatural death, one which is quite as much a death by violence as that by the sword or bullet; when it deprives thousands of the necessaries of life, places them under conditions in which they cannot live — forces them, through the strong arm of the law, to remain in such conditions until that death ensues which is the inevitable consequence — knows that these thousands of victims must perish, and yet permits these conditions to remain, its deed is murder just as surely as the deed of the single individual; disguised, malicious murder, murder against which none can defend himself, which does not seem what it is, because no man sees the murderer, because the death of the victim seems a natural one, since the offense is more one of omission than of commission. But murder it remains. I have now to prove that society in England daily and hourly commits what the working-men’s organs, with perfect correctness, characterize as social murder, that it has placed the workers under conditions in which they can neither retain health nor live long; that it undermines the vital force of these workers gradually, little by little, and so hurries them to the grave before their time. I have further to prove that society knows how injurious such conditions are to the health and the life of the workers, and yet does nothing to improve these conditions.32

By necessity, our economy functioning makes masses of people more miserable (and, in this case, sick). By doing so, the revolutionary hopes, it digs its own grave, for these degraded and humiliated masses won’t put up with it forever.

We are on fire, and so is the Earth we stand on. Everyone is burning, forced to watch as their bodies diminish, their mental state degrades, the ground gives way beneath their feet. Our lives slip away from under our noses as if they belonged to someone else, because they do. Can we wield that fire, our pain, and use it to destroy our conditions or will it just obliterate us all the quicker? Like most incendiaries, the original SPK couldn’t burn for too long: the first group broke up in 1971, with some eventually fleeing to Italy to work with Basaglia or France to work with Guattari, and others ended up in prison or deceased. It has been claimed and contested that a few others were involved with the Red Army Faction (RAF) armed struggle in the 1970s.33 Though they represented an extreme reaction to psychiatric power, the SPK were something of a harbinger for a reckoning with Germany’s psychiatric past, though one without their broader social critique. In the coming years, between 1971–75, the Federal Republic under Willy Brandt produced a major report of the state of Germany’s institutions called the Psychiatrie-Enquete, which revealed continued devastation: “denial of privacy in mass sleeping rooms with no individual cupboards; deprivation of dignity by shaving the hairs of patients and letting them wear gray asylum clothes; brain operations; electro shock therapy and sterilization practices; hazardous medicalisation…meals were withheld and disciplinary measures were inflicted.”34 It would take the remainder of the decade for the profession and the public to seriously reckon with their activities under Nazi rule in the way the SPK already had in 1970.

In practice, the formal SPK was a failed experiment, but their theory rings true wherever illness, debilitation, disability, or brokenness are appropriated as a condition of solidarity. It rang true for the Young Lords in 1970 when they occupied the Lincoln Mental Health Center in the Bronx along with paraprofessionals, locals, some doctors and patients, decrying the disconnection between the mostly affluent white staff and their clientele, and the fatal consequences of medical care based on efficiency and profit. They demanded destigmatized drug treatments, noncarceral and consensual care relations, and propagandized about the political nature of health. Despite major conflicts with the police, they actually won funding for their People’s Program, which they used to fund acupuncture treatments and lead testing, and offered some diagnostic services with a mobile chest x-ray vehicle they seized from the city until they were permanently booted from the hospital by the police in 1978.35

One hears echoes of the solidaristic potential of illness in the productions of the International Network of Alternatives to Psychiatry when, in their founding statement from 1975, they characterized the mad and disabled as workers out of work, the unemployed, and therefore fundamentally part of any movement against capitalist form of life.36 A similar spirit is infused in the marvelous “Statement from the Psychiatrized” delivered by Yves-Luc Conreur at the 1977 meeting for the Network in Trieste:

We, a group of psychiatrized, do not claim to exercise a monopoly over “what is to be done.” We attribute our importance and our force to the fact that we have victoriously opened a path that was unimaginable until now, thereby freeing us from a desperate situation. We do not intend to act in the place of anyone, but to demonstrate concretely to certain people that the real field of possibilities is greater than it might have seemed. We reject magical forms of conduct, we reject artificial and voluntary misery, mysticism, suicide, and madness as forms of liberation. But in order to struggle, in order to give birth to the force necessary to struggle, we must participate personally in the political struggle that leads to the transformation of reality; for that is the only way of discovering the mechanisms of oppression. And once we have understood that that repression is growing in all domains, prisons, class forms of justice, the rhythms of factory life, buying on credit, suburban life, the ghettos of immigrant workers, etc., we can no longer fortify our position behind the fetish of legality. Our truth is not to be found in the projects of our benefactors but in our own always renewed struggles. There will always be an alternative to the alternative.37

Normality may be built of stone or steel, but one day, it will crumble and rust. We are all disabled or on our way there; we all have a little bit of madness or will soon. We are united in the dynamism of our separations, our failures, and our shortcomings, limited only by our inability to appropriate them against a common nightmare. [...]

According to Henry Miller, the clown is identical to “the story which he enacts.” He invites us to partake in life’s constant flux, offering us the “gift of surrender.”38 The clown inhabits a world where the lowest scoundrels can find love just before the haughtiest king falls plopping into muck. And yet, if it is a space imbued with magic, we also know that not all magic is benevolent. The English word for clown originally referred to an uneducated peasant. The veil of irreality enshrouding the spectacle of clownery may subvert the expected, but, at its worst, it merely ritualizes it, allowing an audience to guiltlessly laugh at the physical deformity of “freaks” or to revel in the cruelty of watching the Auguste character, the “one who gets slapped,” cry out in pain. That captive human beings have been put on display under the big tent in colonial expositions and the Jim Crow South shows it to be a place where the deepest malevolence dwells.

Responding to the question “can the mad organize themselves?” there are, at this juncture, three equally true answers. Yes, the mad already informally organize themselves wherever they talk openly about their pain and strengths, meet in group homes or on street corners, exchange cigarettes or secrets. The mad organize themselves in every psych ward, every clubhouse, and every asylum in the world. No, not towards new horizons, because madness is so thoroughly awash in the phantasmagoria of a million mental health markets that present few openings for anything beyond the modification of the language used by service providers. And, finally, not for long, because “the mad” cannot organize themselves without madness itself negating the effort and transmuting it to new forms. Without question, it is folly to gather under the circus tent of madness to plot the end of the world, ludicrous to imagine finding resonance surrounded by distorting funhouse mirrors. Efforts to think madness as such or to organize around it in the past quickly evaporated. The fact is: there has been no mass movement of the mad as mad, there have been few psych ward riots, few sustained revolts of genius and fantasy against tyrannical reason that didn’t come to settle into their own form of reason. The madness of madness absolutely forbids this as it deviously transforms all efforts to make it appear into its exact opposite, sanity. Madness beckons from an elsewhere that’s here and now and expects a response. Madness may in the end be nothing, but it has been, and it will become the fate of millions. If it’s nothing, then it’s a nothing that grabs hold of boundaries and corrodes them with its acidic drool while polarizing opposing terms to the farthest imaginable reaches. Perhaps one day we crushed ones, we losers, we self-destroyers, we rats will pile up into a rat king and move like a wave of ten million would-be suicides across the Earth, obliterating our labyrinth in the process. On that day, we’ll chew up all the money and spit it out of our rabid, frothing mouths into the drain, gleefully sending it back to the nothingness from which it came — in place of our friends, for once. Understood through the weeping gaze of the clown, to set out with and through madness as a process belonging to all of us — somewhere between common exchange and adulteration — is to adopt a fundamentally ethical posture. From the position of a captive humanity forever whirling around in its circulus — the vortex-like racetrack from which the circus derives its name — madness reveals the essential truths of the world only to parade them in a blurry masquerade making its way around a winding orbit. But, unlike the cosmic powerhouses churning at the axes of Andromeda and the Milky Way, activating systems of thermodynamic relays, there is only stale air in the center. It is here — denied the assurance of soil, flung round with glee or nausea, glimpsing only ephemeral markers to guide our passage — where we are called together by some mad howl to act and to find each other.

Storming Bedlam: Madness, Utopia, and Revolt is now available from Common Notions.

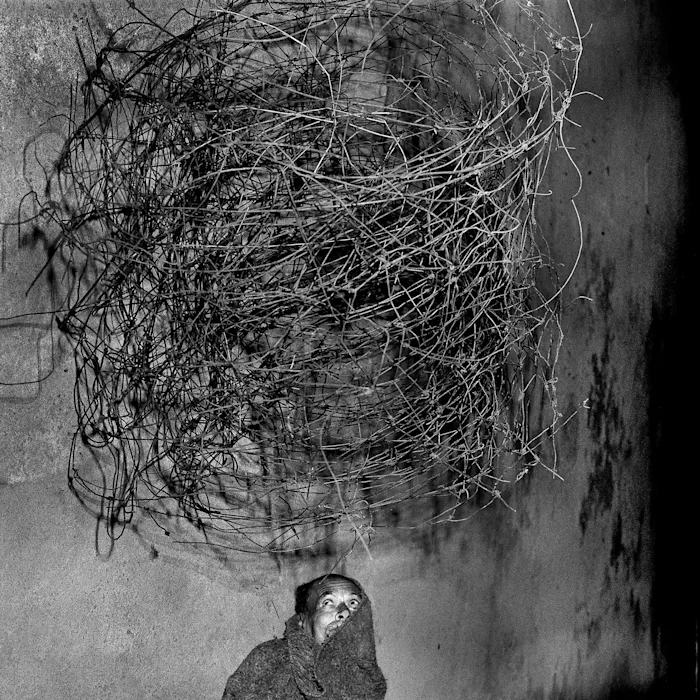

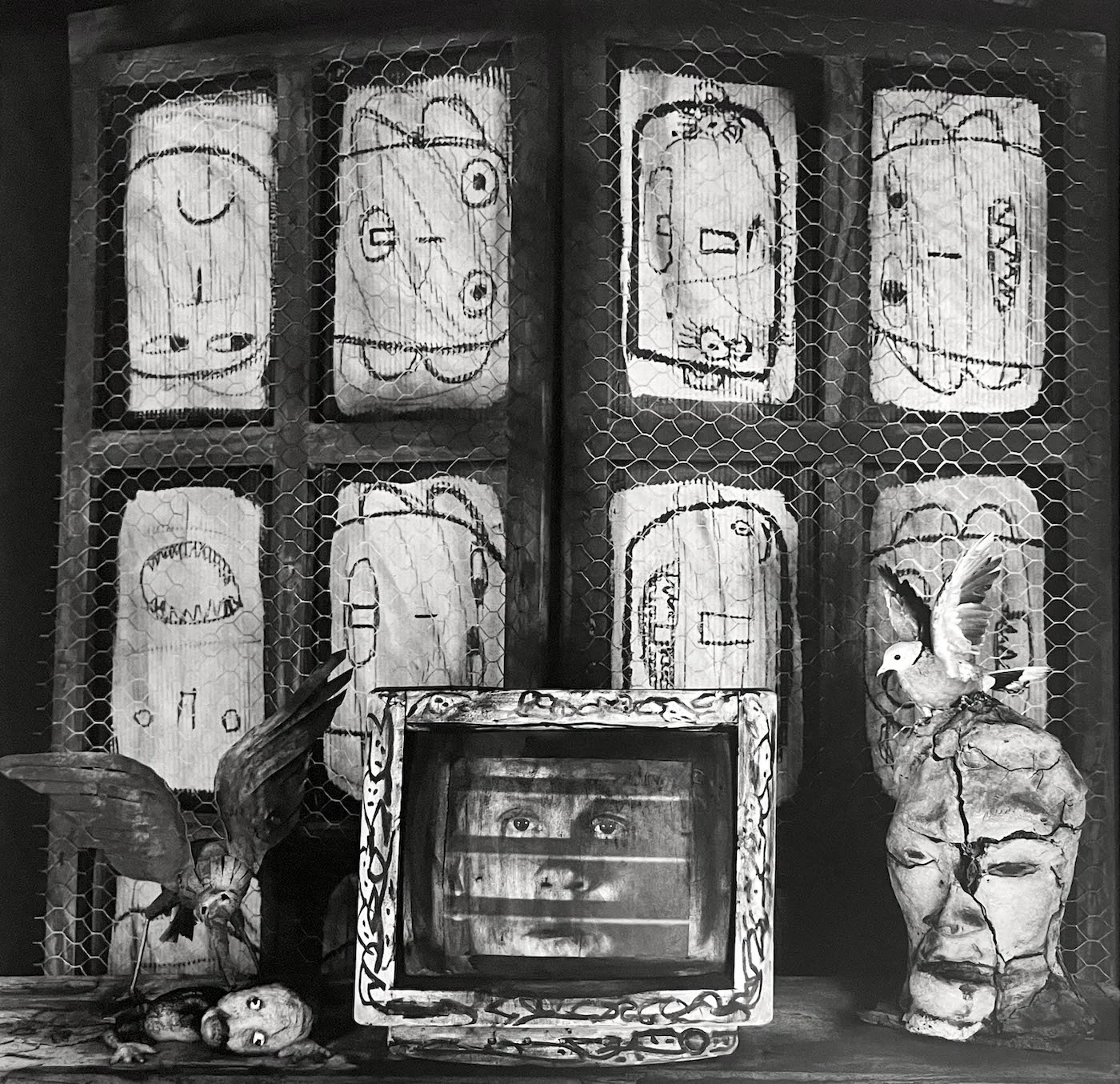

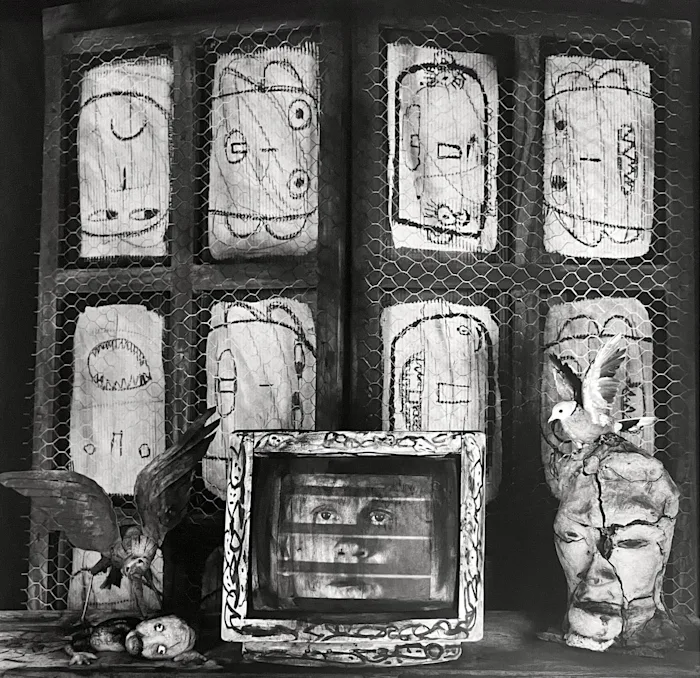

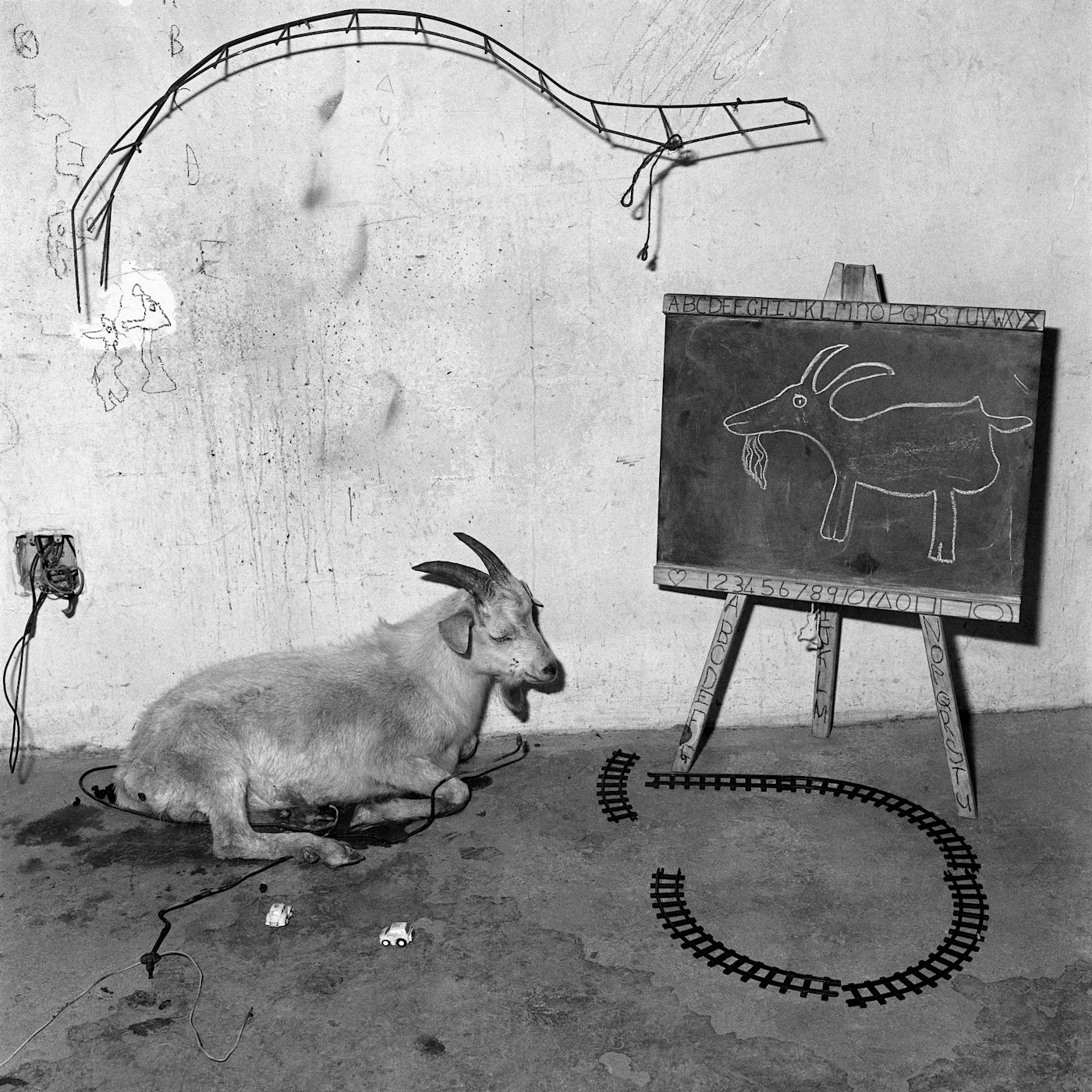

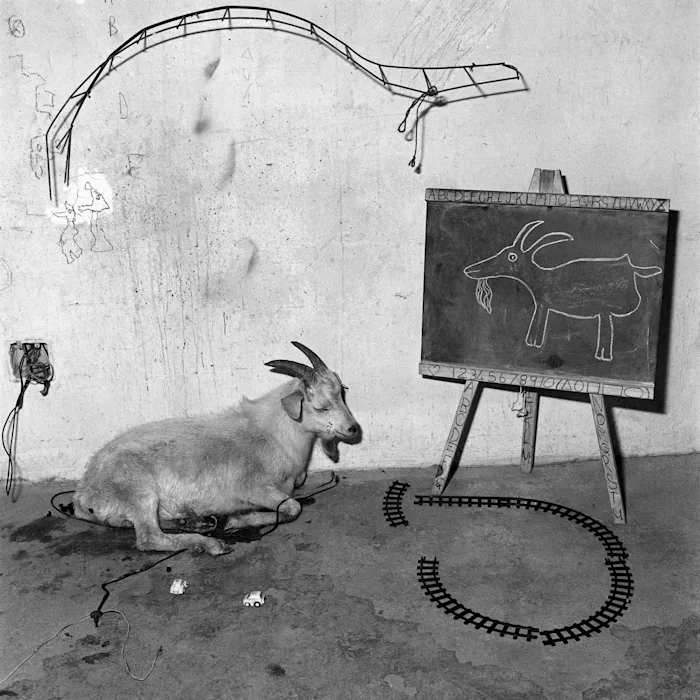

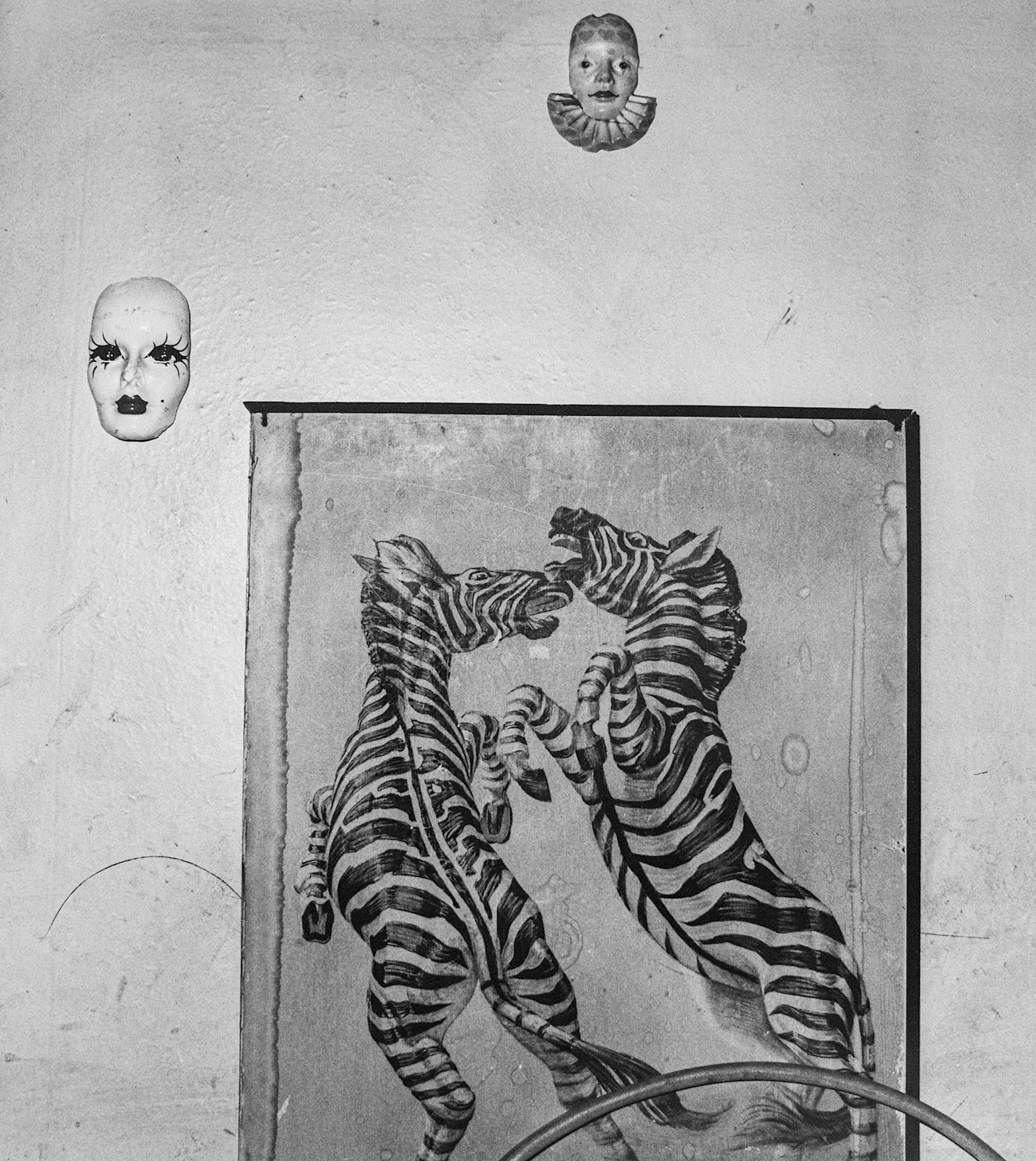

Images: Roger Ballen

Notes

1. Geronimo, Fire and Flames: A History of the German Autonomist Movement, PM Press, 2012, 27–28.↰

2. George Katsiaficas, The Subversion of Politics: European Autonomous Social Movements and the Decolonization of Everyday Life, AK Press, 1997, 60–63.↰

3. Christian Pross, “Revolution and Madness – The ‘Socialist Patients’ Collective of Heidelberg (SPK)’: An Episode in the History of Antipsychiatry and the 1960s Student Rebellion in West Germany,” self-published, 2016, 7–8 (online here); Hugo Bütrer, “From the Pleasure Principle to the Wolves’ Philosophy,” The German Issue, ed. Sylvère Lotringer, Semiotext(e), 2009, 197. For more, see Cornelia Brink, Grenzen der Anstalt. Psychiatrie und Gesellschaft in Deutschland 1860–1980, Wallstein Verlag, 2010, 434.↰

4. Pross, “Revolution and Madness,” 6.↰

5. Brink, Grenzen der Anstalt, 435.↰

6. Socialist Patients’ Collective, “Turn Illness into a Weapon,” Indybay, 2013, 7–8 (online here). I have opted to use the unofficial translation posted on Indybay as opposed to the one Huber himself put out in 1973. The latter is, by his own admission, very unsatisfactory and borders on unreadable in parts. The more recent unofficial translation is much more accurate and smooth. Sometimes, I will include the original German in brackets, if it makes my argument clearer or if there is an ambiguous meaning.↰

7. This unfortunately still continues with a group calling themselves PF-SPK (Patient Front-Socialist Patients’ Collective). Texts from recent decades released under that name are broadly and stereotypically medical-conspiratorial, which in my view is a major departure from the contributions of the SPK in Turn Illness into a Weapon. This newer group has gone so far as to deny the existence of AIDS, COVID-19, and other conditions as mere “machinations” of doctors. They seem to be very keen on revising the past by claiming the SPK had no involvement with the movement of ’68, antipsychiatry, or other social movements, something which is easily falsifiable by looking at their own texts and participant observations. To that end, they have published statements denouncing individuals who write about their past in a way they disapprove of. I don’t reference or discuss these newer texts in the main body of the book because I see no reason to believe this new formation is representative of the group that formed around 1970 and published Turn Illness into a Weapon.↰

8. Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon, 1.↰

9. Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon, 59.↰

10. Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon, 2.↰

11. Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, trans. Martin Milligan, Prometheus Books, 1988, 74.↰

12. Quoted in Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon, 59.↰

13. Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon, 59.↰

14. Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon, 2.↰

15. Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon, 6.↰

16. Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon, 79.↰

17. Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon, 8.↰

18. Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon, 26.↰

19. Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon, 60.↰

20. Unidentified member speaking in Gerd Kroske (dir.), SPK Komplex. Germany: Realistfilm and Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (RBB) 2018, Vimeo (online here).↰

21. Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon, 59.↰

22. Dora García and Carmen Roll, “An Interview with Carmen Roll,” Mad Marginal, Cahier #1: From Basaglia to Brazil, Mousse, 2010, 150. Online here.↰

23. Ana Antić, “Decolonizing Madness? Transcultural Psychiatry, International Order and Birth of a ‘Global Psyche’ in the Aftermath of the Second World War,” Journal of Global History 17, no. 1 (2022): 24.↰

24. Antić, “Decolonizing Madness?,” 27.↰

25. Antić, “Decolonizing Madness?,” 31.↰

26. For a summary and critique of the arguments presented here, see Chapter 3 of Nikolas Rose, Our Psychiatric Future, Polity, 2019.↰

27. Ethan Watters, Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche, Robinson Publishing, 2011.↰

28. China Mills, Decolonizing Global Mental Health: The Psychiatrization of the Majority World, Routledge, 2014.↰

29. Liat Ben-Moshe, Decarcerating Disability: Deinstitutionalization and Prison Abolition, University of Minnesota Press, 2020, 60–62. Richard Warner offers further quantitative evidence for this claim in Recovery from Schizophrenia: Psychiatry and Political Economy, Brunner-Routledge, 1997, 87.↰

30. Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon, 83.↰

31. Quoted in Socialist Patients’ Collective, Turn Illness into a Weapon,102.↰

32. Friedrich Engels, The Condition of the Working-Class in England, Progress Publishers, 1980, 120–121↰

33. The most up-to-date history and literature overview on the controversy in English is in Beatrice Adler-Bolton and Artie Vierkant, Health Communism, Verso, 2022, 154–178.↰

34. Anne Klein, “Governing Madness––Transforming Psychiatry: Disability History and the Formation of Cultural Knowledge in West Germany in the 1970s and 1980s,” Moving the Social 53 (2015): 24. Online here.↰

35. Sessi Kuwabara Blanchard, “How the Young Lords Took Lincoln Hospital, Left a Health Activism Legacy,” Filter, October 30, 2018. Online here.↰

36. David Cooper, The Language of Madness, Penguin Books, 1978, 171.↰

37. Yves-Luc Conreur, “A Statement from the Psychiatrized,” State and Mind: People Look at Psychology 6, no. 2 (Winter 1977): 1. Courtesy of the Oskar Diethelm Library, DeWitt Institute for the History of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College.↰