Imaginary Enemies:

Myth and Abolition in the Minneapolis Rebellion

Nevada

The following article from a friend in Minneapolis looks at the impact in rebellions of what is known as the “fog of war”, or the strategic problem of “unknowability.” In the case of the George Floyd rebellion, the author argues that this unknowability played out particularly along racial lines. On the one hand, the participation of white antagonists helped the uprising to quickly take on a scale beyond anyone’s comprehension, resulting in a situation that was both ungovernable and unknowable in terms of the makeup of its partisans. At the same time, as counter-insurgent forces fought to restore order, they too seized upon this uncertainty by producing the mythological threat of the white supremacist outside agitator. The unknowable represents a threat with which all future rebellions will have to contend, especially in the U.S. context.

Other languages: Français

Author’s note: The following is an edited transcript of a talk delivered across the street from the burnt remains of the 3rd Precinct on October 29th in Minneapolis, MN. The author wishes to thank those present for the discussion, as well as the editors at Ill Will for their feedback.

This past summer, I sat down to write a letter to my friends in the international collective Liaisons about the uprising in my city of Minneapolis. This letter was inspired by news of police in Richmond, Virginia accusing the participants of a July Black Lives Matter demonstration of being white supremacist agitators in disguise, intent on causing destruction — accusations that we had already seen here at the end of May. More recently, rumors to this effect have circulated online about the unrest in Philadelphia after the police murdered Walter Wallace Jr. at the end of October. My letter attempted to illuminate how the state used the fictional or exaggerated figure of the “white supremacist agitator” to perpetuate anti-Blackness and capitalist property relations by facilitating the mass organization of auxiliary policing groups. Minnesota Governor Tim Walz and Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey led an effort to cast rioters as white supremacists coming from outside of Minnesota to destroy our cities. This precipitated the mass, independent organization of auxiliary law enforcement in the form of neighborhood watches and community patrols to stop these supposed white supremacists.

As revolutionaries, we must ask ourselves why, at the height of what was easily the largest rebellion in over half a century, much of the city organized to assist the police in crushing it, often in the name of the very anti-racism at its heart? My aim here is to assess the role of the “white supremacist outside agitator” as a discursive figure in the counter-insurgent strategy of the state, so that partisans may more effectively counter it in the next uprising.

In what follows, I will analyze three elements that, although they arose organically from the rebellion itself, nonetheless laid the groundwork for the state’s narrative white supremacist agitation. These three elements are, first, the visible presence of the far-right in the first days of the uprising; second, white participation in the revolt; and third, the way the revolt quickly assumed a geographic and political scale that was beyond the comprehension of both observers and participants. Together, these elements undermined the traditional political narratives that framed what people expected to see from a rebellion against racism and the police. This opened the situation to competing narratives by which to make sense of white participation and the presence of white supremacists, including one that held white supremacists responsible for the violence of the rebellion. I explain how this narrative divided much of the sympathetic base of the uprising against it, which deprived rebels of popular support and allowed them to be crushed by the National Guard, thereby preserving the very order that was the enemy of the revolt.

Speculation on white supremacist involvement began already on the first night of the uprising. A handful of Boogaloo Bois drove down from suburbs like New Brighton to join the clashes that had been taking place all evening on May 26 outside the 3rd Precinct. This is not the place to examine their ideology in detail, but suffice it to say that, despite their far-right positions, some of them saw the murder of George Floyd as the unjust action of a corrupt police department and affirmed the uprising as a valid response to it. They photographed themselves with their flag in the streets (their images were widely circulated online) and then left soon afterwards. In the next few days, this group of Boogaloo Bois received an upsurge of attention, starting with anti-fascist activists who attempted to alert demonstrators of their presence, marginal though it was.1

Regardless of whether the Boogaloo Bois did in fact view the escalating conflict in the streets of Minneapolis as a righteous cause, or merely as a means to bringing about their “civil war” with the government, the revolt exploded far beyond their narrow vision. Just as with the Yellow Vests of France, the mass looting of shopping districts pushed the movement tactically beyond where the far-right was willing to go. They were thus given two options: to participate in an uprising that centers Black liberation (and thus de-centers their own ideology) or to let themselves be sidelined and left behind by the uprising.2

By the second day of the revolt, many Boogaloo Bois had already relegated themselves to defending private property in response to the widespread looting. A video that circulated on social media from the second day shows a group of them outside of GM Tobacco between the Target and the Cub Foods, walking a tightrope on which they try to balance “supporting the uprising” while protecting the store from the uprising. A week later, the narrative of white supremacist rioters allowed social justice groups seeking to defend private property to more easily navigate a similar tightrope. This led to an ironic turn of events in the case of Minnesota Freedom Riders (also known as the Northside Patrol, made up of groups like the NAACP and city councilor Jeremiah Ellison), which collaborated with these same Boogaloo Bois to protect stores from vague threats of white supremacists — despite themselves being the only group visible on the ground associated with these threats. Just as this irony was lost on most, so too was the contradiction between the narrative of white supremacist rioters and the facts of the matter, namely, that the most prominent far-right presence in the uprising was engaged in the defense of capitalist property, not its destruction.

Despite the centrality of Black liberation in the George Floyd Rebellion, it cannot be said that the uprising was entirely Black. People from every conceivable demographic and identity participated in it. In his piece “How It Might Should Be Done,” Idris Robinson uses the metaphor of an avant-garde to describe Black participation in the revolt. He states “We were the avant-garde who spearheaded it, we set it off, we initiated it. What ensued was a wildly multi-ethnic uprising.” Skepticism or suspicion of white participants is understandable, yet was relatively uncommon during the first few days of the revolt. However, by the fifth night, it had become a dominant reflex, due to the emerging paranoia around white supremacist involvement. White participants in the streets who broke the law were assumed to be outside agitators — if not white supremacists — without any other evidence than their skin tone. In the midst of tear gas, shattered windows, and hails of rocks, people were pressed to identify themselves and, in some cases, to give their street addresses. Those who refused were even sometimes attacked.

As has been discussed elsewhere, to blame what happened on outsiders or provocateurs robs the rebellion of its power, by delegitimizing it along with its participants. And we should not forget the racist history of the “outside agitator” as a tool of counter-insurgency, which was a narrative originally used to explain slave revolts, as enslaved Blacks were said to be docile until stirred up by white abolitionists from the North.3 Beyond disempowering rebels and reproducing racist tropes, however, I want to insist on the legitimacy of white abolitionists who decide to join the frontlines. The truth is that we all have a stake in Black liberation. As Fred Moten once said, “I just need you to recognize that this shit is killing you, too, however much more softly, you stupid motherfucker.”4

The revolt in May occurred on an unprecedented scale. As we know, the 3rd Precinct was the epicenter of the first three days of unrest, before the police inside were forced to flee, before the precinct was burned, and before the focus of the crowds moved on to other targets, including the 5th Precinct which very nearly almost fell as well. However, even before the burning of the 3rd Precinct, crowds flowed outwards from the epicenter and brought unrest across the city, into Saint Paul, and even into the suburbs. While the first crowds kept many officers pinned down at the precinct, these swarms would assemble in other areas to loot and burn stores — generally with the assistance of cars, where a group of people would pull up, break in, grab what they could, and peel out before police could respond. In other words, from the very start, the rebellion was also a mass phenomenon of smash-and-grabs.

In attempting to make sense of the early stages of the rebellion, inherited logics of both representative protest and of militant protest fail us. From the perspective of representational politics, those who were swarming and looting stores across the city were not “protesting,” as their actions did not present a grievance for which they sought recognition. That is, these actions were not only deviations from “legitimate political protest,” they opportunistically took advantage of such protests by using them for private gain. In reality, however, the looters were directly abolishing property relations, which are inextricable from the violence of anti-Blackness. Let us recall that the order of private property is what killed George Floyd in the first place. It is one thing to hold a sign that says “redistribute the wealth;” it is another to decide that all that shit on the store shelves is ours for the taking — and take it.5

While it is commonplace to adopt the frame of representational politics and to dismiss looting as opportunistic, when such looting and destruction turned to stores that ostensibly identified with the cause of social justice — primarily Black and other minority-owned businesses — they were often deemed malicious, or worse. The crudest form of identity politics involved postulating that these stores could not have been targeted for any other reason than racist motivations. There was often no evidence for this speculation; it was posited as self-evident. In the most absurd of cases, corporate stores falsely labeled themselves as “Black-owned,” either by writing it on plywood boards like modern-day lamb’s blood, or by those protecting them to legitimate their defense of property. But if we cease to view every act of property destruction or looting as an expression of a grievance, this logic begins to erode. It is not my intention to argue that minority-owned stores should be targeted, but that such incidents do not offer any insight into participants’ racial or ideological backgrounds.

Instead, I argue that this created a new division within the uprising that helped to transform it into a “militant” protest movement. Here, the classic dichotomy between the “good protester” and the “bad protester” was replaced by the dichotomy between the “good rioter” and the “bad rioter.” In other words, rioters were now divided into those whose militant action can still be understood within the grammar of protest (fighting the police or attacking a corporate department store) and those whose actions exceed and escape this traditional understanding.

After four days, the upheaval had spread far beyond what anyone could have anticipated. Refusing to play by the rules of non-violence, it escaped the trap of representational protest. Its composition was too diverse to be neatly categorized by any demographic or political affiliation. Then, on the morning of May 30, Governor Walz hosted a press conference describing the rioters as white supremacist outsiders who were out to destroy the city. He was followed by both Minneapolis and St Paul mayors, who fabricated statistics to back up those claims — only to be quietly retracted days later. Online rumors were amplified and misinformation was circulated at truly dizzying speeds. In the midst of the chaos, they offered a legible and understandable enemy to all of those who were searching for stability, but could not be mobilized by the explicitly racist rhetoric of “Black looters,” or the right-wing’s fear-mongering about “antifa.” This fear would instead be ascribed to the face of evil par excellence: the white supremacist.

Blaming the violence of the uprising on “white supremacists” allowed the state to undermine the anti-police rage of the rebellion and resume its prior role of protecting citizens against extremism. The state intentionally shifted the target of people’s anger from the systemic racism that murdered George Floyd (and countless others) to relatively marginal actors. In my letter to Liaisons, I identified this as the rhetorical figure of synecdoche, a movement from part to whole, or whole to part. The location of white supremacy and anti-Blackness is displaced onto an extremist part — a small assortment of bad actors — that only serves to mask their true whereabouts in the heart of civil society as a whole.

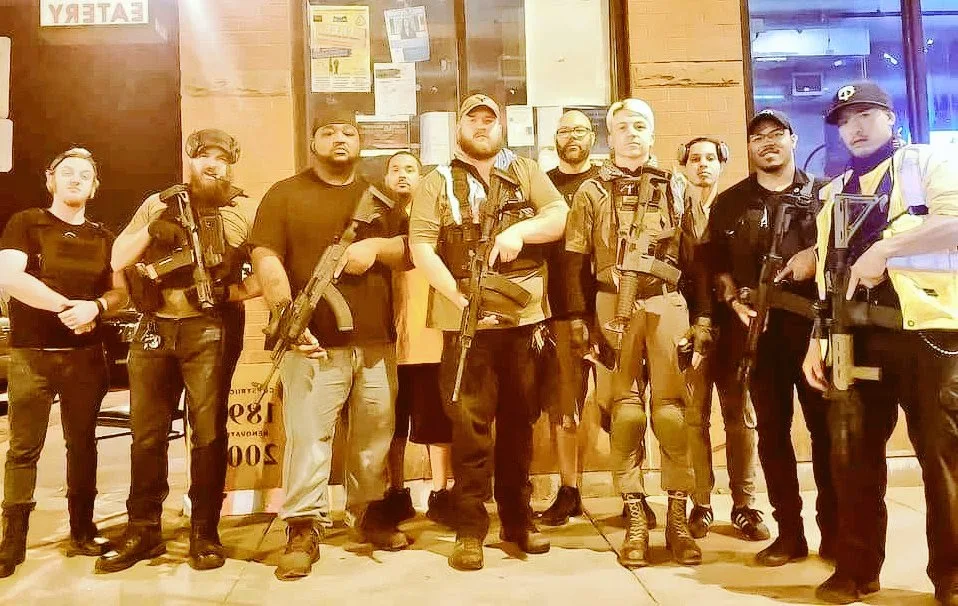

This displacement made room for a new alliance between social-justice advocates and anti-fascists on the one hand and vigilante law enforcement on the other. While police were forced to retreat, this alliance was forged with new neighborhood watch groups and citizen patrols protecting against the lawlessness of the riots. Armed patrols guarded businesses, while smaller roads were blocked by citizens who performed ID checks. After curfew, citizens’ checkpoints allowed only residents and police to pass, while many more stayed home in fear of vague threats of indiscriminate violence. Frightened citizens called the FBI to report out-of-state license plates, while others preferred taking to social media to spread rumors and report “sketchy activity.” Meanwhile, the National Guard had little trouble mass-arresting the few who dared to continue defying the curfew.

These patrols varied from neighborhood to neighborhood, block to block. They were also ideologically diverse, and while they might not have directly collaborated with one another, they all effectively accomplished the same goals. In some areas, white homeowners sat on their porches and called the police on neighbors they’d never met whom they deemed to be suspicious. There were of course many small business owners who armed themselves to protect their stores, such as the owner of Cadillac Pawn on Lake Street, who murdered Calvin Horton Jr. Majority-Black and Native American neighborhoods also set up their own armed patrols, often with the help of nonprofits that considered themselves an extension of the protests (or at least in support of them). Examples include the Minnesota Freedom Riders that I mentioned above (who collaborated with the armed far-right) and the American Indian Movement (AIM) patrol near Little Earth, a majority-Native neighborhood. The AIM patrol was celebrated for its role in protecting property, including the apprehension of some white teenagers for looting a liquor store that had been broken into two nights before.

Patrols like these justified their actions along racial lines. However, like AIM, they consistently helped protect white-owned businesses, corporations, and banks. In some cases, these patrols inadvertently ended up protecting racist property owners who just happened to be located on their “beat,” but even in those cases where businesses were truly owned by racial or ethnic minority groups, these patrols and their valorization of property “structurally” aligned them with the forces of civil order. As Idris Robinson observed, “whenever property is protected, it is protected for white supremacist ends.”6

The formation and alignment of racially diverse neighborhood patrols in defense of private property was only possible by way of a counterinsurgent, synecdochal displacement that identified violence with white supremacy. This is the only way that such a massive project could emerge so quickly and with such popular support. This counterinsurgent initiative even cloaked itself in the language of police abolition, with neighbors suggesting that they were “prefiguring” what would replace the Minneapolis Police Department when it was abolished, with no concern for the fact that they were assuming the enforcement of the very same legal order here and now. Truth be told, they are not wrong. The type of police abolition that has gripped the city’s imagination is merely the same regime of law, only upheld by nicer faces. Instead of police, there are to be “community security forces” — or the “office of violence prevention” (which has recently emerged here in Minneapolis). The only effect such institutions could ever have would be to integrate the population ever more profoundly into the police operations that already govern their lives today.

The figure of the white supremacist agitator does not simply tarnish the memory and legacy of the revolt. It also illuminates the very stakes of the movement itself and its call for abolition. It must be said that revolutionary abolition does not simply mean the defunding of any specific department, as many activists advocate today. Nor does revolutionary abolition does simply mean doing away with the brutality that police use to enforce the law, as offered by restorative justice.7 Instead, revolutionary abolition must mean the abolition of law itself, along with the property relations that the law upholds.

In May, we witnessed a revolt of such magnitude and ferocity that it has no equal in this country for at least half a century. We can see the rubble from it still, all around us. To be sure, revolution consists of so much more than merely burning and fighting, but it does involve these actions. These actions were at the very heart of the uprising this Summer. To condemn them is to condemn the uprising.

Just as we approached the precipice of total insurrection, stability and order were reintroduced to the city, when nothing seemed less likely. The next time revolt erupts in our streets, let us be prepared to resist the reimposition of law and order, no matter how “radically” it presents itself.

—Nevada Minneapolis, November 2020

Notes

1. In Minnesota, the state’s attention to Boogaloo Bois continued months after the attack on the 3rd Precinct. On October 24th, the FBI charged a Boogaloo Boi for shooting his gun at the 3rd Precinct after it was surrendered by the police on May 28th. This relatively minor act was magnified by news media outlets to falsely portray the destruction of the police building as the work of white supremacist agitators.↰

2. This insight comes from the essay “Memes With Force.” The authors argue that, in the logic of Yellow Vests movement, there lies a way out of the traditional political narratives to which I refer here. Before going on to show how looting and vandalism marginalized the influence of the far-right, they urge us to see “radical actions,” not “radical actors”: “Contemporary politics sees in action nothing but a conversation between constituencies and populations in society. It is for this reason that, when radical activity emerges in a way that is relatively anonymous, that lacks a consistent author, and persistently refuses to answer to our compositional (‘who are you?’) and projectual questions (‘why are you doing this?’), it tends to be unrecognizable to political analysts and activists alike. It is precisely this received wisdom that the Yellow Vests have been laying to waste, week after week. What is emerging today in France is a radical form of collective action that does not rely on a coherent ideology, motivation, participant, or regional location. Above all, it is not proceeding by means of a dialogue with its enemy.” (Paul Torino and Adrian Wohlleben, “Memes With Force: Lessons from the Yellow Vests,” Mute, February 26, 2019.) In Anarcho-Blackness: Notes Toward A Black Anarchism, Marquis Bey, themselves citing Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s The Undercommons, also meditates on this refusal of ideological exclusion: “Upon a re-reading of The Undercommons, I was drawn, obsessively, to one phrase, one that struck me at first as dangerously wrongheaded. But, then, the revolutionary will always be dangerous. The revolutionary call that Moten and Harney require and that I’ve been obsessed with is this: they insist that our radical politics, our anarchic world-building must be ‘unconditional—the door swings open for refuge even though it may let in police agents and destruction’. As my grandmother might quip, what kind of foolishness is this? But it is not foolishness precisely because the only ethical call that could bring about the radical revolutionary overturning we seek is one that does not discriminate or develop criteria for inclusion and, consequently, exclusion.”↰

3. For further analysis of the “outside agitator” as a strategy of delegitimation, with historical comparisons to the George Floyd Rebellion, see “The Anti-Black and Anti-Semitic History of ‘Outside Agitators’: An Interview with Spencer Sunshine,” It’s Going Down, June 2, 2020. ↰

4. In an interview from 2013, Moten discusses Fred Hampton’s statement, “White power to white people. Black power to black people.” Moten follows: “What I think he meant is, look: the problematic of coalition is that coalition isn’t something that emerges so that you can come help me, a maneuver that always gets traced back to your own interests. The coalition emerges out of your recognition that it’s fucked up for you, in the same way that we’ve already recognized that it’s fucked up for us. I don’t need your help. I just need you to recognize that this shit is killing you, too, however much more softly, you stupid motherfucker, you know?” See Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study, edited by Erik Empson (New York: Minor Compositions, 2013),140-141. On this connection, see Shemon and Arturo’s article on the participation of white people in the revolt and its significance. See Shemon and Arturo, “The Return of John Brown: White Race Traitors In The 2020 Uprising.”↰

5. I am building off of what philosopher Giorgio Agamben has proposed to call a destituent power, which has influenced the writings of other revolutionaries on the uprising, such as a piece that appeared in CrimethInc. earlier this summer: “Unlike protests, which employ a means (e.g., a march or a blockade) to reach an end (e.g., sending a message or making demands), the events of the uprising […] blur this distinction. They create a kind of means-as-end, or means-without-end, in which the purpose is inextricable from the lived experience of the event itself. To fuse means and ends in this way, we have to move beyond the predetermined choreography of protest to a more transformative paradigm of action. ‘I’ll never forget that night’ reads the latest graffiti written on the barricades surrounding the precinct, referring to the night of May 28 on which unrelenting crowds forced police to retreat from their station and established a brief yet real police-free zone—abolition in real time.” (“July 4 in Minneapolis: The Logic of Autonomous Organizing,” CrimethInc., July 6, 2020.) ↰

6. Idris Robinson has argued that the attack on this inner connection between race and property was at the heart of the George Floyd Rebellion. He says: “[W]hitey loves property. Property enjoys a special prestige in American life, it has a special kind of sanctity. […] There is a very important reason that property has this particular kind of sanctity in America, as many historians are starting to confirm and argue. For most of its history, the most important property in America was human property, shackled and chained. We need to weaponize this argument, and say that whenever property is protected, it is protected for white supremacist ends. If property is truly the pursuit of happiness, in that trifecta of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, the existence of that happiness and property is premised upon the negation of Black life and the negation of Black liberty. So the protection of property is something that we need to attack explicitly.” (Idris Robinson, “How It Might Should Be Done,” Ill Will, July 20, 2020.) In her recent book, In Defense of Looting, Vicky Osterweil traces the inextricable history of race, settler-colonialism, and property, building off thinkers such as Cedric Robinson, who coined the term ‘racial capitalism.’ The thrust of what I have written here can be summed up by the following passage from her book: “Not only is capitalist development completely reliant on racialized forms of power, but bourgeois legality itself, enshrining at its center the right to own property, fundamentally relies on racial structures of human nature to justify this right. Private property is a racial concept, and race, a propertarian one.” Vicky Osterweil, In Defense of Looting: A Riotous History of Uncivil Action (New York: Bold Type Books, 2020), 36.↰

7. As Frank B. Wilderson has put it, “I’m not against police brutality, I’m against the police.” See his 2015 interview with IMIXWHATILIKE. On the crucial distinction between restorative and transformative justice, see Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement, ed. Ejeris Dixon & Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha.↰