Imagination, or Absolute Life

Rodrigo Karmy

Other languages: Italiano

A virus and an uprising traverse the world. A microorganism of genetic material that inserts itself into a cell and infects it; a popular irruption within a State that does not welcome it. Virus and revolt are two names for the 21st century: on the one hand, we have cells invaded by a stranger who puts them under threat; on the other, we have weakened states traversed by foreigners that enact their destitution, and exhibit their inoperativity. Perhaps viruses and revolt are even two names for the same problem, a fundamentally spectrological one.

As we know, a virus is not a cell, but a molecular assemblage. To the extent that the cell constitutes the most primordial unit of life according to biological science, the virus cannot be considered something “alive”. Similarly, revolt today is neither the work of a party or a regime but, like the virus, it is a popular assemblage that does not allow itself to be clearly defined in the language of “politics”, if by politics we understand the institutional locus of sovereignty. Neither the virus nor the revolt becomes what they parasitize, since both are defined by a “lack of being”: both enact a disjoining of the reigning ontological regimes, whether this be the sovereign primacy of the “autopoietic” notion of the cell, or the “autarky” signified by the political regime.

Is a virus dead or alive? Is a revolt political or unpolitical? Let us say that the virus and the revolt that proliferate today across the planet have a convergent spectrology, in which the living and the non-living, the impolitical and the political experience a “point of intersection”, as the young Italian Egyptologist as Furio Jesi claims in his Spartakus — a sequence that mixes each side to such a degree that the totality becomes spectral or, as I prefer, imaginal.

The potentiality of the imaginal can, in this sense, in no way be attributed exclusively to “animal” capacities, as Aristotle had done, but is rather the medium through which all things experience the disjunction of being: the living overlaps with the non-living, creating a point of intersection between cosmology and anthropology, a medium or intermezzo between two polarities. In this sense, the imaginal is not reducible to “information” if by this we understand binary sequences and automated modulation, since the cybernetic hypothesis is always ultimately about the regulation of order. The imaginal doesn’t claim cartographical space but rather a topological one. We could say, following Heidegger´s suggestion, that the imagination is without “homeland” [Heimat]: it is the counterforce that destitutes every form, every order that lays claim to sovereignty, including the form of governmentality by which Michel Foucault described the late modern — and Christian — configuration of power.

The irruption of both the virus and the revolt are ways of embracing our existence through the mode of the imagination, that is, the spectral dimension in which the living and the non-living, the human and the non-human converge. That is what the phenomenologist Henry Corbin has argued in reference to Suhrawardi’s term, “mundus imaginalis”. The imagination leaves nothing in its right place. Everything in it rises, floats and initiates a process of becoming precisely because it is “out of place”, outside the general order of things.

In other words, the virus and the revolt are two modes of the same imaginal intensity that cut across our epoch without epoch. Their rhythm enacts a dissemination of ontological purity. Seen from this vantage point, ethnic, linguistic or culturally identitarian appeals become absurd since, in the imagination, all “identity” is traversed by the other of itself, and interrupted by the sensible roar that runs through it.

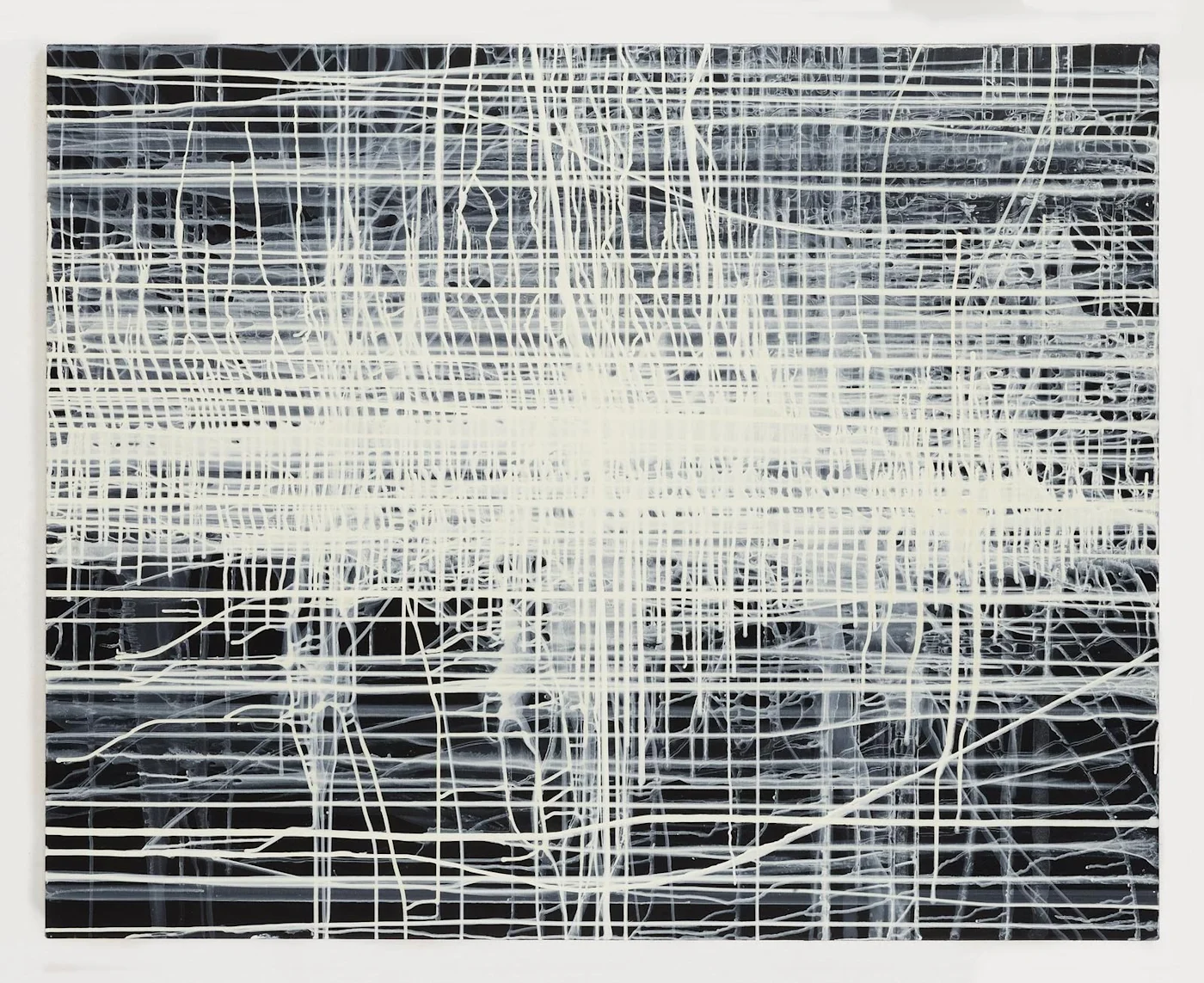

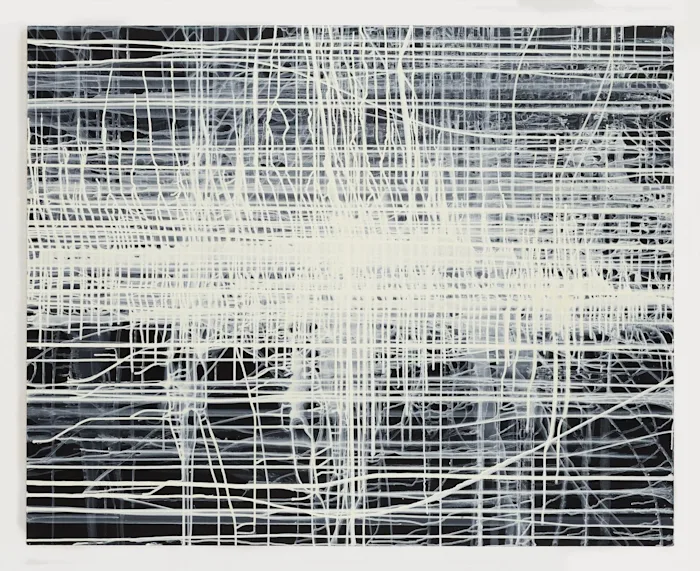

“Intensity” is the name of all things, while potentiality is what escapes every dominant cartography: included neither in the anatomical scene, nor in the forms of government. Intensity criss-crosses, bursts in, reaches the table without invitation, knocks on the door like a foreigner who takes us out of ourselves embracing us in the common intensity that designates thought. Indeed, this is the “place of spectrology”, as Jacques Derrida called it (this is also consistent with what Edward Said called “mixture”). It is a place without a place (a khorá, as Plato tells us) — that is, a medium where every form becomes other from itself.

This topology makes up the strange place where the virus and the uprising become modes of the imagination, as a singular crystallization — a sort of epiphany — of the overflow that abysses and, nevertheless, offers polyform rhythms and multiple sequences. Viruses and revolts are not the names that restore the classical metaphysical opposition between nature and culture, but two ways to describe the infinite intensity of the imagination in which the non-living and the living mercilessly cross each other.

Furio Jesi gave the name “double Sophia” to the irruption of mythical eternity within historical contingency, the advent of potentiality and its singular crystallization. “Double Sophia” becomes the privileged term to designate not only revolt, but the constitutive disjunction of everything that exists. Overwhelmed doctors, overwhelmed politicians, overwhelmed times: viruses are the immanent revolt at the cellular level, while the revolt is the immanent virus of all political institutions, capable of forcing the mutation of things at a molecular level beyond any planning.

The imaginal in its becoming is nothing other than what we might call experience, a medial disjunction in which something like the living can take place. The imaginal condition is life, or more precisely, absolute life, because it cannot be reduced to any form, since it can only make possible every kind of form. Perhaps we could also think of imagination as absolute life, not unlike the concept of “magma” in Castoriadis’ philosophy, or that “mundus imaginalis” in Corbin’s thought.

Viruses and revolts are two kinds of monsters that arise against unity, because they bring to us the outside of existence, the little window that could be opened when we are confined by the pandemic, or the soft gesture of a revolt that destitutes the closure of every political order. Destitution is not destruction, it is to give a new possibility to the world, a new use of bodies, as Giorgio Agamben says. While destruction is the violence of a revolutionary vanguard, destitution is the imaginal potentiality of “whatever being”, that disables the operativity of every system and makes impossible any vanguard. This is also why destitution is not a “power” but a “potentiality”. A “power” implies the capture of imagination in some order (what Sigmund Freud called “illusion”); potentiality, instead, releases new forms of life.

This is why absolute life should not be considered as within a “system” (a totality of articulated parts), but rather as the eternal diffraction of life from itself. Hence, there are not simply “viruses” or “revolts”; today we are bearing witness to dual modes of imagination that move beyond the caesura of “nature” or “culture” to allow for experience. An experience that names that medial region that serves to remind us that we are never either simply alive nor dead.

November, 2020

First delivered at The Undercommons and Destituent Power conference, organized by Indiana University. A video transcript, followed by a Q&A, may be found here.

The author wishes to thank Gerardo Muñoz for his help with the translation.