Lectures on the Virus

William S. Burroughs

Preface

Not only did William S. Burroughs anticipate the meme wars of the digital era, but his most direct inheritors must today be sought beyond critical theory and art, among insurgent and activist circles. Burroughs’ writings about viruses transformed during his lifetime, and a proper critical history of his theory has yet to be written. But beyond the published works, perhaps no archival document contains as much substance and profundity as Burroughs’ lectures on his theory of virality at the City College of New York, delivered as part of a semester-length course on creative writing. 1974 was a pivotal moment in the authors’ life. He had only recently returned to America after twenty-five years of exile, and the Downtown scene in New York City was on the rise.

"Using the virus as a prototype, we can arrive at a general field theory or description of evil."1 If it is remembered at all, Burroughs’ theory of the virus is often treated merely as a “metaphor for the power of the media.”2 This, however, is too reductive. The figure of the virus applies not only to the media, but also describes the circulatory logic of information within systems and relationships of spectacular power that, in Burroughs’ “hyperbolic, and perhaps parodic Manichaestic” ethical universe, serve as the very epitome of evil.3 On the one hand, what is at stake is a general theory of communication, which, in the class sessions preceding his discussion of the virus, he glosses as follows:

In the last class I was considering control systems and the essential role played in control systems by communication. Here’s a definition of communication: it causes different effects with intention, attention, and duplication. Now, communication is the action of propelling an impulse from a source point across a distance to a receiver point with the intention of bringing into being at the receipt point a duplication of that which emanated from the source point. I think that’s a fairly good definition. That is, when you talk, you’re trying to recreate a duplication of your meaning at the other end of the terminal. Now the source points can be words spoken, radio, T.V., images, gestures, odors, tactile communications. It doesn’t necessarily have to be verbal. However, we must have a source point for communication. There must be distance no matter however long or short, that is to say another terminal. There is, of course, a communication at all times within the body itself, but still involving distance. Say from the stomach back to brain communicating hunger and so forth. In fact some investigators have attributed cancer to a breakdown in the entire internal communications system of the body.

However, Burroughs at the same time insists on the inexorable connection that all communication technology maintains with structures of control and domination. As he argues, “all control systems need communication. And by far, the most useful form of communication for control purposes is words.” It is for this reason that we must situate Burroughs’ exploration of virality within the wider avant-garde search for methods of descrambling and resisting symbolic standards of control, communication, and surveillance.

In the twentieth century, viruses became central not just to fields of theoretical epidemiology or computer science, but also to the avant-garde of post-structuralist philosophy. Jacques Derrida observed that, if we understand the virus as a disruptive parasite that scrambles writing and is itself neither living nor dead, then his entire philosophical oeuvre can be placed under the sign of virality.4 Burroughs’ influence on these theoretical domains has long been recognized.5 At the Nova Convention in 1978, Burroughs was honored by Gilles Deleuze and Michel Foucault alike for his prophetic work, and his work would later serve as the basis for Deleuze’s critique of neoliberal power in his 1992 essay, “Postscript on Societies of Control.” For his part, the American deconstructionist J. Hillis Miller applied virological theory to the meta-critique of critical discourse itself. As he writes,

[T]he parasite is an alien who has not simply the ability to invade a domestic enclosure, consume the food of the family, and kill the host, but the strange capacity, in doing all that, to turn the host into multitudinous proliferating replications of itself. [...] The genetic pattern of the virus is so coded that it can enter a host cell and violently reprogram all the genetic material in that cell, turning the cell into a little factory for manufacturing copies of itself, so destroying it.6

The insight that the parasite must keep its hosts alive in order to survive appears variously across Burroughs’ work.7

These lectures — a selection of which is offered below — offer a good example of Burroughs’ pedagogical method, which weaves together increasingly complicated concepts until reaching a pinnacle in his theory of communication and the virus. They signal a concerted attempt to explain himself in colloquial terms. Burroughs ties the course’s theme of creative writing to a broad theory of the virus that implicates communication systems, cinematic methods of montage, and literary methods of collage. His speculations lead him to play with ideas in a fantastical and mythologizing tone resembling his fiction, such as when he flirts with the eugenicist idea that racial differentiation could be the result of viral contagion and mutation.

At the same time, we also find one of his clearest articulations of his theory of evil as virality, i.e., a fascist need for control and exploitation, the very antithesis of mutually beneficial relationships. Alongside this critique of ideological control and radicalization, Burroughs probes the homology between epidemiology and the new media and cybernetic ecosystems of power, criticizing the capitalist system for encouraging parasitic relationships, like a doctor motivated to keep his business alive by not curing the patient, or a communication technology that depends on rewarding users with ever more spectacular consumer experiences and scandalous news. He points to the important relation between immunology and communication networks, interpreting cancer as a failure of the body to communicate with itself.

Is Burroughs guilty of what Susan Sontag described, in her 1978 essay “Illness as Metaphor,” as a misuse of the metaphor of illness? Not only did Burroughs’ exploration of the virus influence Sontag’s own thinking, but the theme is so pervasive in his work that answering such a question would require a wider reconsideration of his countercultural politics and aesthetics in its significance in the contemporary context. With any luck, the publication of these lectures will inspire others to delve further into his archive and his published works alike, much of which might prove useful to a critique of the ideological contradictions surrounding public health and epidemiology that are so painfully manifest in the media and daily life today.

—Alex Wermer-Colan

May 3, 1974, City College of New York

Now consider an example of totally destructive communication where precise duplication is intended and, in fact, achieved.8 The example is virus infection which precisely fits the communication formula. Cause, distance, effect, intention, attention, and duplication. We can, I think, attribute intention, if nothing else, to a virus, which certainly exhibits what Korzybski has called “intentional behavior.” It calls attention to itself in a way that cannot be ignored, and duplicates itself precisely. Action of impelling particle. Hachoo — a sneeze across a distance to a receipt point. The sneeze reaches the susceptible host, bringing into being, after a receipt point, a duplication of that which emanated from the source. Duplication of virus particles that were in the cell, which released themselves, duplicated themselves with other cells, and finally released the host to infect other hosts. The virus has achieved a precision of communication with respect to the duplication of that which emanates from the source point — far in advance of human speech.

Speech is a partial means of communication and, in most cases, designed and intended to be partial. In fact, most verbal exchange is concerned with concealment, misdirection, and evasion, and does not intend to deliver any precise duplication of what emanates from the source point. The actual intention may be concealed. Words are made to lie with. Despite this lack of precision with the effect produced, words are the most potent control instrument when used on a mass scale, as we can see through the mass effectiveness of propaganda techniques. Words are a partially effective control instrument and cut-ups — that is, cutting up lines — provide a partial counter.9

A picture language sentence is a statement of events in a certain order in time. The word order is picked, and the picture language depends on the juxtaposition for sense, and on a juxtaposition that does not change. Permutating this sentence, you do not get new or altered meanings… The word order is the meaning.

The grammar virus has the same unalterable order. Here’s the influenza virus exposure: susceptible host, attachment of the virus to a cell wall, penetration of the cell wall, replication within the cell, release from the cell to infect other cells, and finally release from the host to invade another susceptible host. Any alteration or permutation of this order, and the intention is lost. Infection does not occur, or is arrested.

Cut-ups are more devastating when used against a more precise form of communication. Now consider the use of cut-ups to nullify admittedly imprecise control systems, aiming for statistical rather than dramatic effect. It’s difficult to know how precise the control system is, as put down by the Daily Press. You cut the mutter line of the mass media and put the altered mutter line out in the streets with a tape recorder. Consider the mutter line of the Daily Press. It goes up with the morning papers and millions of people read the same words, chewing, swearing, chuckling, and reacting to the same words in different ways, of course, but all reacting. Emotion craving Mr. Callahan’s action in banging the South African critic. Tourist boiled the colonel’s breakfast. All reacting one way or another to the paper world of unseen events which become an integral part of your reality.10

The simplest cut up is to cut a page down the middle and cross the middle into four sections. Section one is then in the place of section 4 and section 3 is in the place of section 2. Carried further, we can break the page down into smaller and smaller units in all sequences. The original purpose of scrambling devices was to make the message unintelligible without the unscrambling code. Another use for speech scramblers was to impose thought control on a mass scale. Consider the human body and nervous system as unscrambling devices. A common virus like the cold sore could sensitize the subject to unscramble messages. Drugs like LSD and DDM could also act as unscrambling devices. Moreover, the mass media could sensitize millions of people to the same scrambled versions of the same set of data. Remember that when the human nervous system unscrambles a scrambled message, it will seem to the subject like his very own idea which has just occurred to him, which indeed it did. Pick a card, any card. In most cases, he will not suspect its extraneous origin. That is the run of the mill newspaper reader who reflects his own opinion, independently arrived at. On the other hand, the subject may recognize or suspect the extraneous origin of voices that are literally hatching out of his head.

Then we have the classic syndrome of paranoid psychosis. The subject hears voices. Anyone can be made to hear voices with scrambling techniques. It is not difficult to expose him to the actual scrambled message, any part of which can be made intelligible. This can be done with street recorders, recorders in cars, doctored radio and TV sets in his own flat if possible, if not in some bar or restaurant. If he doesn’t talk to himself, he soon will. The buggy is flat. Now he’s really around the bend hearing his own voice out of radio and TV broadcasts and in the conversation of passing strangers. See how easy it is. Remember the scrambled message is partially unintelligible and in any case it gives the tone. It is partially intelligible.

Research projects to find out to what extent scrambled messages are unscrambled, that is scanned out, by experimental subjects. The simplest experiment consists in playing back a scrambled message to the subject. The message could contain simple commandments. Does the scrambled message have any command value comparable to posthypnotic suggestion? [...]

Is the actual content of the message received? What drugs, if any, increase the ability to unscramble messages? Do subjects vary widely in this ability? Are scrambled messages in the subject’s own voice more effective than messages in other voices, or are they less effective? Probably less. Are messages scrambled in certain voices more easily unscrambled by specific subjects? Is the message more potent with both word and image scrambled on videotape? Now use for example, a videotape message with a unified emotional content. Let us say the message is fear. For this we take all the past fear shots of the subject we can collect or evoke. We cut these in with fear words and pictures, with threats and so forth. This is all acted out and would be upsetting enough in any case. Now let’s try it scrambled and see if we can get an even stronger effect.

To what extent can physical illness be induced by scrambled illness tapes? Take, for example, a color and sound picture of a subject with a cold. Later when the subject is fully recovered, we take color and sound film of the recovered subject. We now scramble the cold picture and sound track in with present sound and image track. We also project the cold picture on further pictures.

Could seeing and hearing this sound and image track scrambled down to very small units bring about an attack of cold virus? If such a cold tape does lead to an attack of cold virus, we cannot say that we have created a virus. At best, we have merely activated a latent virus. Many viruses, as you know, are latent in the body and may be activated. We could try the same with a cold sore, with hepatitis, always remembering that we may be activating a latent virus, and in no sense creating a laboratory virus. However, we may be in a position to do this. Is a virus perhaps, simply very small units of sound and image? Remember the only image the virus has is the image and sound track it can impose on you, the effects it causes. The yellow eyes of jaundice, the pustules of smallpox that are imposed on you against your will. The same is certainly true of scrambled words and images. Its existence is the word and image it can make you unscramble. Pick a card, any card. This does not mean it is actually a virus. Perhaps to construct a laboratory virus, we would need both camera and sound crew, and a biochemist as well.

I quote from the International Paris Tribune from an article on synthetic genes by Dr. Howard Carama, who made a gene synthetically, a gene particle: “It is the beginning of the end,” he said. This was the immediate reaction to the news from the science attaché from one of Washington’s major embassies:

If you can make genes, you can eventually make new viruses for which there are no cures. Any little country with good biochemists could make this biological weapon; it would take only a small laboratory. If it can be done, somebody will do it. For example, a death virus could be created to carry the coded message of death.

No doubt the technical details are complex, and perhaps a team of sound and camera men working with biochemists could give us the answer.

Now the question is whether scrambling techniques could be used to spread helpful and pleasant messages. Perhaps. On the other hand, the scrambled word and tape act like a virus in that they force something on the subject against his will. More to the point would be to discover how the old scanning patterns could be altered so the subject liberates his own spontaneous scanning pattern, and this would give him a measure of immunity to scrambled speech.

Now, all this is readily subject to experimental verification on control subjects. Neither need the equipment be all that complicated. The simplest scanning device is scissors and splicing equipment. You can start with two tape recorders. You could start scrambling words, make any kinds of tapes and scramble them, and observe the effects on friends and on yourself. The next step is sound film and then video camera. Of course, the results from individual experiments could lead to mass experiments. The possibility here for research and experiment is virtually unlimited, and I have made just a few simple suggestions.

A virus is characterized and limited by obligate cellular parasites. All viruses must parasitize living cells for their replication. For all viruses, the infection cycle consists in entering into a host, intercellular replication, and escape from the body of the host to initiate a new cycle in a fresh host. I’m quoting here from “Mechanisms of Virus Infections,” edited by Dr. Wilson Smith:

This will state that the virus is not truly a very adaptable organism. Some viruses burn themselves out, since they were 100% fatal and there were no reservoirs. Each strain of virus is rigidly programmed for a certain attack on certain tissues. If the attack fails, the virus does not gain a new host.

There are, of course, viral mutations, and the influenza virus has proven to be quite versatile in this regard. Generally, it’s the simple repetition of the same method of answering. And if that method is blocked by anybody or other agencies, such as by interference, the attack will fail. By in large, a virus is a stupid organism. Now we can think for the virus, and devise a number of alternate methods of entry. We have considered the possibility that the virus can be activated or even created by various small units of sound and image. So conceived, the virus can be made to order in the laboratory. However, for the tapes to be successful, you must have the actual virus. And what is this actual virus? New viruses turn up from time to time, but from where do they turn up? Well, let’s see how we could make a virus turn up. We plot now our virus’ symptoms and make a scrambled tape. The most susceptible subjects, that is, those who reproduce some of the desired symptoms, will then be scrambled into more tape until we scramble our virus into existence. This birth of a virus occurs when our virus is able to reproduce itself in a host and pass itself on to another host.

I suggested that viruses can be created to order in the laboratories from very small units of sound and image. Such a preparation in itself is not biologically active, but it could activate or even create a virus in susceptible subjects.

May 8, 1974

The last class, I proposed the virus as a prototype of evil, or rather as a prototype that gives some significance to the time that makes it usable. All writers have concerned themselves with the question of evil and what evil is. Because, no evil, no conflict; and no conflict, no story. You’ve got to have bad guys and good guys. But as Korzybski points out, evil or any other more verbal formulation does not exist in a Platonic vacuum. It can only be defined or described, and Korzybski says that descriptions are more useful, since they are less rigid than definitions.

Described, then, as something done at some definite time and place, by and to some definite person or persons. So people with different interests at definite times and places will consequently have different concepts of good and evil. The South African reaction to a recent book explicitly treating sex relations between white and black was that there was evil on every page. So what definition or description can emerge from this welter of conflicting interests? Every group or individual defining evil in terms of interests: this is an evil contract if it is not at all to my advantage. However, using the virus as a prototype, we can arrive at a general field theory or description of evil. Certainly most of the trouble on this planet is caused by people who cannot or will not mind their own business because they have no business of their own to mind. Their business is exploiting, oppressing, coercing, controlling, inflaming, and, in some cases, exterminating others. In other words, evil is essentially parasitic. The virus is an obligate cellular parasite, with no other business than invading host cells, replicating its image within the cells and then infecting another host. Admittedly, some are much worse than others. A cold is a minor evil compared with rabies. But who wants a cold? You do not need the virus; the virus needs you. You don’t need evil, evil needs you. Evil is basically parasitic. Now the Boers in South Africa need the Blacks; the Blacks do not need them.

Evil may be considered, not as the knowledge of good and evil, as defined in the Bible, but good or evil, which is the conflict formula between men and nations. Not room for both of us in this space — either/or. This is the formula of the virus: you or me. If you are the smallpox virus, then the virus can only survive by imposing disadvantages and, in some cases, lethal conditions upon the host.

So we now have a working definition to separate the good guys from the bad guys. By and large, the good guys are minding their own business and wishing others would do the same. And who are the bad guys? The bad guys are those who can’t mind their own business because they have no business of their own any more than the smallpox virus. And the hardcore opposition, the hardcore bad guys would be those who could find no business of their own to mind even if they were given the opportunity to do so.

I’ve frequently spoken of words and images as viruses, or else acting as viruses in certain instances. And this is not in all respects an allegorical comparison. It will be seen that the falsification inherent in alphabetic Western languages are in point of fact actually virus mechanisms. If we can infer purpose from behavior, then the purpose of a virus is to survive, to be. Parenthetically, Mr. Hubbard says the purpose of life has now been discovered by him, and it is to survive. And he adds, “the rightest right a man could be would be to live infinitely long.” No comment on that. But certainly the virus survives infinitely long, as long as there are hosts to parasite on, unless the parasite gets greedy and kills all the hosts. And this has happened to several virus strains. For example, the sweats which decimated England in the fifteenth century was in all probability a virus and was 100 percent fatal. And it burned itself out. You have to keep that chain letter in operation. If the chain is broken, the virus has eaten itself out of a home. It’s better from the point of view of survival to be a simple cold sore, content with creating a petty annoyance rather than a spectacular epidemic. The virus then intends to survive, to feed, to be you, or be as much of you as it can be.

Korzybski has proposed to build a language in which certain falsifications inherent to all existing Western languages will be incapable of formulation. The following falsifications need to be deleted from the proposed language: “The ‘is’ of identity”; you are an animal, you are a body. Now whatever you may be, you are not an animal and you are not a body, because these are verbal labels. “The ‘is’ of identity” always carries the implication of that and nothing else, and it also carries the assignment of permanent condition, to stay that way. All name-calling presupposes “the ‘is’ of identity”: that is, it assigns a definite identification with the implication that that is permanent. That’s what you are. [...]

Whatever I may be called upon to be or say that I am, I am not the verbal label “myself.” I cannot be, and I am not the verbal label “myself.” The word “be” in English then contains, as a virus contains, its precoded message of damage. The categorical imperative of permanent condition. To be a body, to be nothing else, to stay a body. To be an animal, to be nothing else, to stay an animal. The categorical “the” is also a virus mechanism locking you in “the” virus universe.

If the virus produces no damaging symptoms, we have no way of ascertaining its existence, and this happens with latent virus infections. I have suggested a virus theory of evolution, which is that biologic changes were made by a virus illness which were then genetically conveyed, and the yellow races may have resulted from a jaundice-like virus, which produced a permanent mutation, not necessarily damaging, which was passed along genetically. That would be a virus of biologic mutation, which simply means that change was produced by a virus illness and this change was then genetically conveyed. This is possible I think but would also mean that the changes occurred quite suddenly rather than doing it slowly. And the word itself may be a virus which has achieved a permanent status with the host. However, no known virus in existence at the present time acts in this manner. So the question of a beneficent virus remains open. As I said, now there are almost no known viruses that have beneficent or useful effects.

“The Mechanism of Virus Infection,” edited by Mr. Wilson Smith: now he’s a scientist that really thinks about his subject, instead of merely correlating his data. He thinks about the ultimate intention of the virus organism, speculating as to the biologic goal of the species. Taking the virus’-eye view, the ideal situation would appear to be one in which the virus replicates itself without in any way disturbing the hosts’ normal metabolism. This has been suggested as the ideal situation toward which all viruses are slowly evolving. And would you offer violence to a well-intentioned virus on its slow road to symbiosis?

Consider the virus. It is an obligate cellular parasite, unlike organisms like the spirochete, or the malarial parasite, or unlike bacteria; there are many beneficent bacteria. In fact we can’t get along without them or bacillus. It is an obligatory parasite; that is, the virus is rigidly programmed to perform a certain operation. Now the existence of a computer program would certainly lead us to infer a programmer, since computers do not program themselves. Can we not infer a virus programmer? If so, we have an alien invasion of many years standing, because the virus is by its nature alien. A parasite must remain alien, that is, different and separate from the host; otherwise, it ceases to be a virus and ceases to be a parasite. It loses its separate existence. A virus without symptoms, that is, a virus which occasions no reaction to the body of the host, would not be noticed. And viruses seemingly must make themselves noticed, must call attention to themselves. Here again is the prototype of evil. Evil is not self-sufficient. Evil must make itself real and call attention to itself at all times. Real as a nightstick, real as jail, concentration camps, and the convulsion of rabies. Otherwise the virus is absorbed and ceases to be a parasite, because it becomes part of the whole.

Excerpted with permission from Burroughs Unbound: William S. Burroughs and the Performance of Writing (2021), out now with Bloomsbury Press. The editors wish to thank both the press and the Burroughs estate for their cooperation.

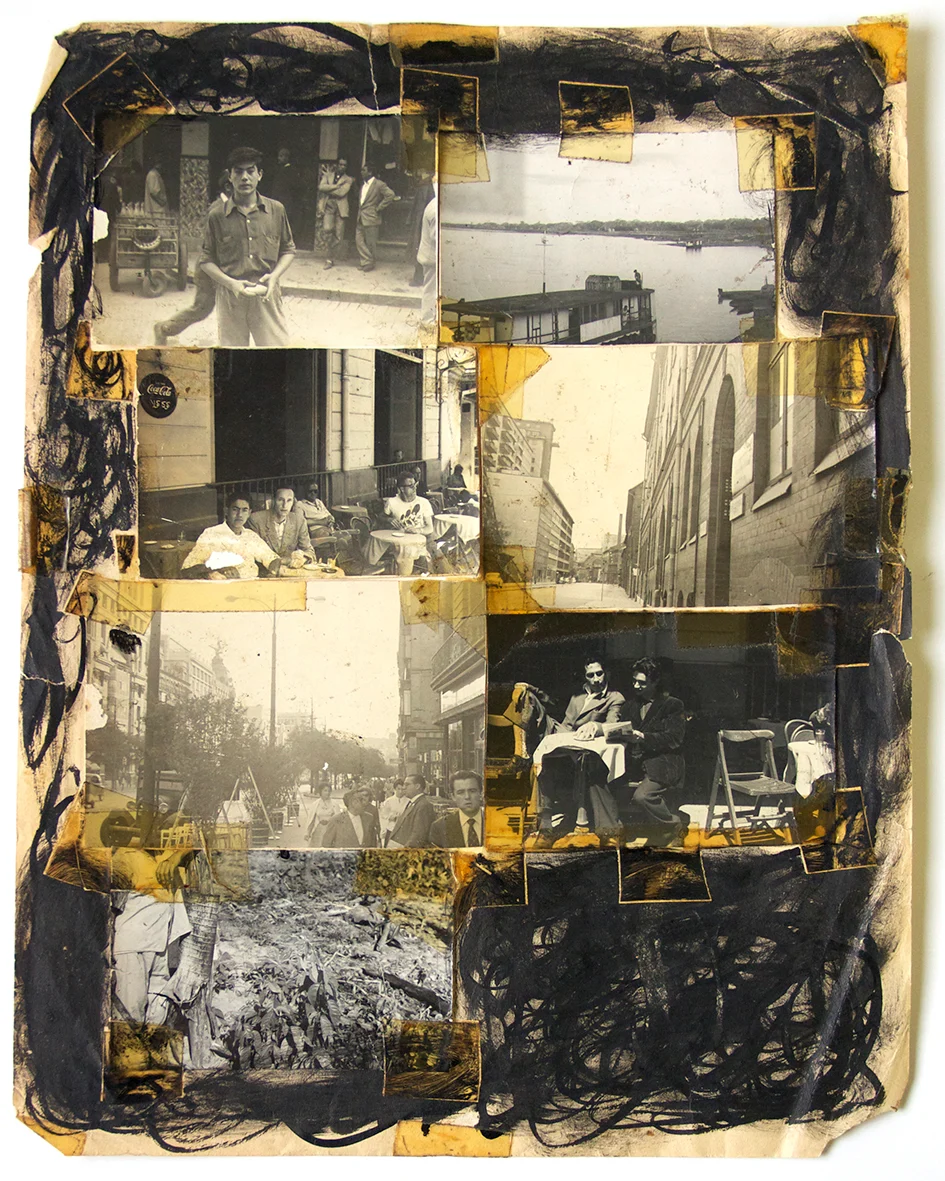

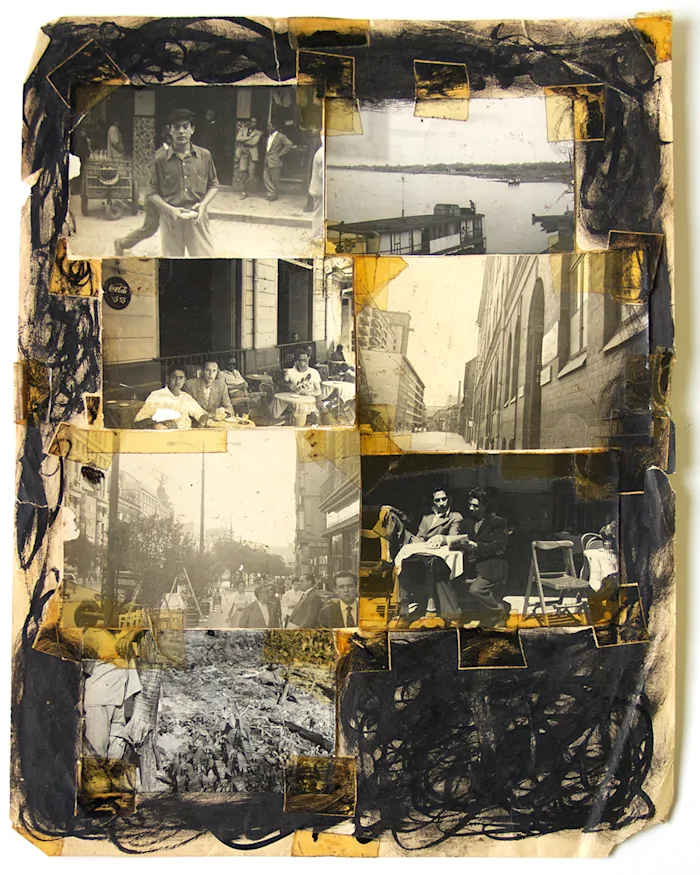

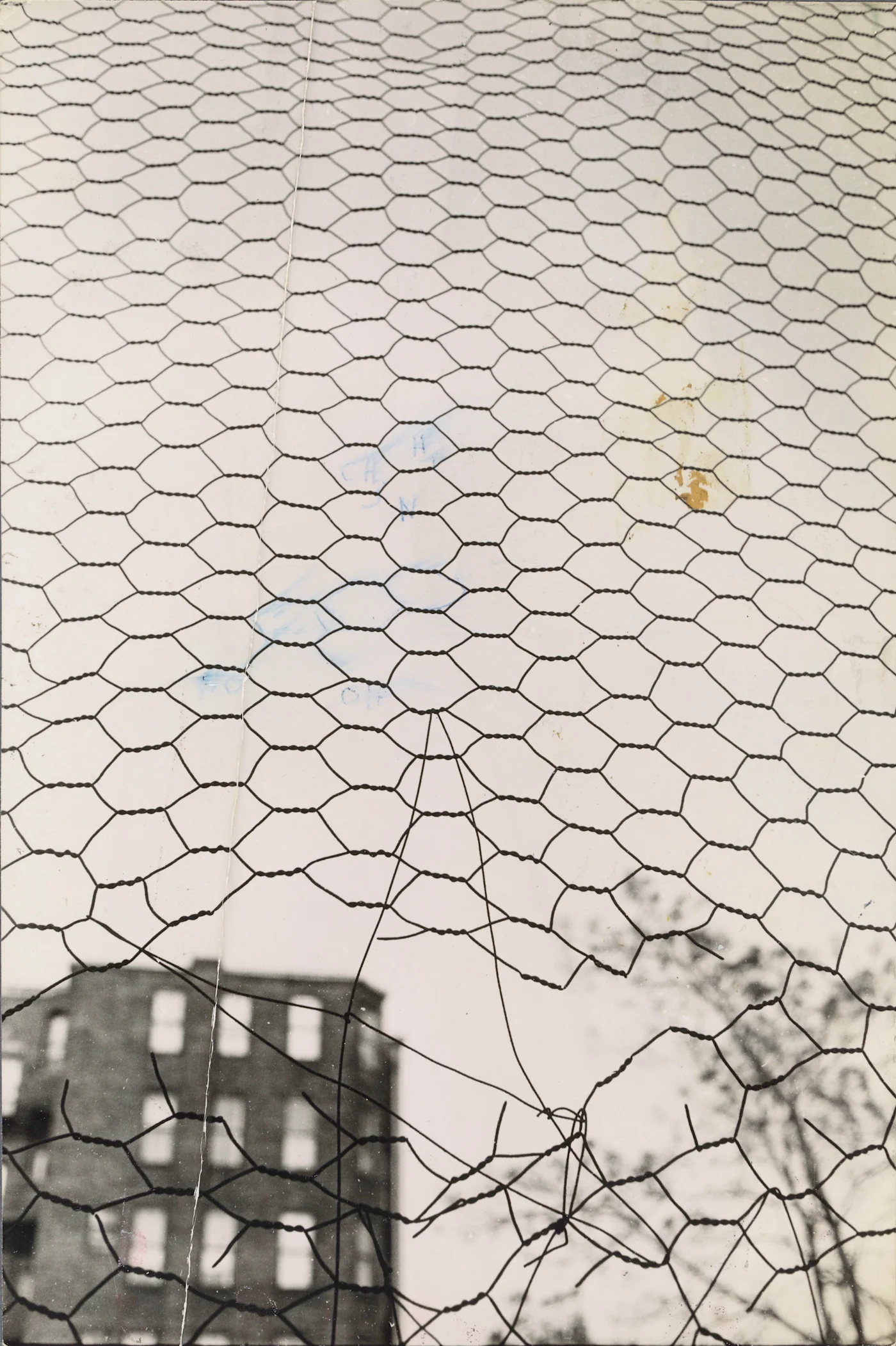

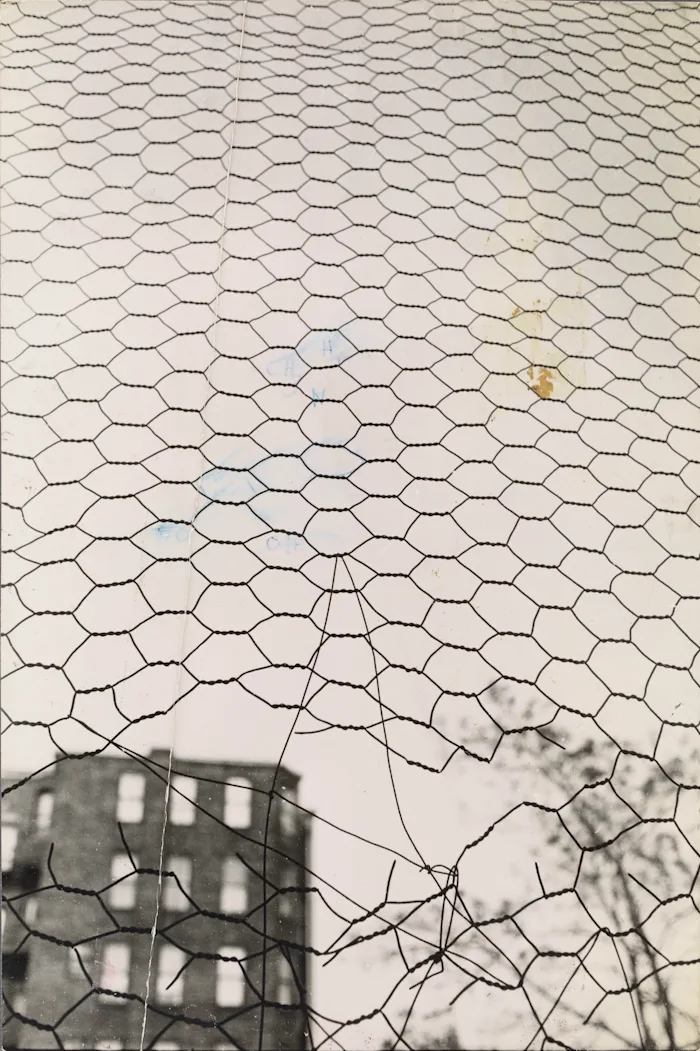

Cover: Loomis Dean In-text images: William S. Burroughs

Notes

1. William S. Burroughs, from a lecture delivered at the City College of New York, May 8, 1974. [All footnotes have been added by the editor. This abridged transcription of Burroughs' lecture notes has also been edited for readability. —Alex Wermer-Colan]↰

2. Scott Bukatman, Terminal Identity: The Virtual Subject in Postmodern Science Fiction, 1993, 76. Burroughs’ theory of the virus is often acknowledged but rarely treated directly. Bukatman’s work is an exception to this pattern.↰

3. Bakatman, ibid. A useful discussion of the virus in Burroughs’ early works can be found in the chapter “Two Sounds of the Virus: William Burroughs’s Pure Meat Method,” in Douglas Kahn’s Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts (2001). A full account of this subject would also have to include a consideration of its intellectual origins, as well as its transformation across his published and unpublished oeuvre from Naked Lunch (1959) and the cut-up novels (1962-68) to Electronic Revolution (1970, 1973) and Cities of Red Night (1981), a novel in which Burroughs envisioned a virus similar to AIDs, yet before the 1980s epidemic.↰

4. “All I have done … is dominated by the thought of a virus, what could be called a parasitology, a virology, the virus being many things…. The virus is in part a parasite that destroys, that introduces disorder into communication. Even from the biological standpoint, this is what happens with a virus; it derails a mechanism of the communicational type, its coding and decoding. On the other hand, it is something that is neither living nor non-living; the virus is not a microbe. And if you follow these two threads, that of a parasite which disrupts destination from the communicative point of view—disrupting writing, inscription, and the coding and decoding of inscription—and which on the other hand is neither alive nor dead, you have the matrix of all that I have done since I began writing.” Jacques Derrida, Brunette & Wills, ed., Deconstruction and the Visual Arts, Cambridge University Press, 1994, page 12.↰

5. See Robin Lydenberg, Word Cultures: Radical Theory and Practice in William S. Burroughs’ Fiction (1987).↰

6. J. Hillis Miller, “The Critic as Host,” 454. ↰

7. See also his interviews published in The Job (1968). More recent scholarship on viral metaphors in the modern era relevant to Burroughs’ virological theories includes Michel Serres’ The Parasite (1980), Peta Mitchell’s Contagious Metaphor (2012), Tony D. Sampson’s Virality: Contagion Theory in the Age of Networks (2012), and Dahlia Schweitzer’s Zombies, Viruses, and the End of the World (2018).↰

8. Burroughs’ CCNY lecture notes and files are contained in their entirety at Ohio State University’s (OSU) Rare Books and Manuscripts Library, CMS.40 Box 46, Folders 447 and 448. The rest of Burroughs’ lecture files are distributed across a series of folders, including CMS.40 Box 44, Folders 428 and 429, and Box 45, Folders 440 and 443. Also held at OSU are the audio recordings of Burroughs’ lectures in CMS.40, Box 45, Folder 443A; the virus lectures, meanwhile, are recorded on Tape N and O. ↰

9. Burroughs expostulates his theory of hieroglyphics versus alphabetic languages in terms of their divergent relationships between signifiers and signifieds, as well as their differing effects. He argues that pictorial languages must occur in a specific order to produce their meaning.↰

10. Burroughs cites Richard C. French’s article in the New Scientist, “Electronic Arts of Non-Communication” (June 4, 1970). He discusses his experiments cutting up tape recordings with Ian Sommerville and Anthony Balch.↰