Malevolent Europe:

Refugee Oppression and Resistance at the Borders

Anonymous

Fleeing war and poverty, a flow of refugees and migrants on a scale unseen in europe seen since WWII are currently making their way into and across Europe. By boat, foot, train and bus they are fighting their way across borders, against police lines, tear-gas, barbed-wire fences and prison-camps. Thousands are dying in the process (an estimated 3000 people have died or have gone missing trying to make it to Europe this year alone); crossing the Mediterranean, suffocating in the back of the trucks of profiteering smugglers, and through generalized social neglect. As European governments squabble in political crisis and the European charity-complex fails to mobilize to provide the basic humanitarian assistance that is necessary, as borders into the Schengen zones are fenced up and razor-wired by prison labour (Hungary), peoples’ movement through Europe presents an unstoppable force of courage, determination and resistance. At the same time as asylum laws are tightened, migrants and refugees further criminalized, and border regimes are made increasingly violent and militarized, resistance to this very regime is growing stronger. Peoples’ refusal to stop at borders, refusal to be contained and isolated in camps, and determination to make it to their desired destination and some kind of freedom and safety, is breaking down the system at the same time as it is being built up.

These are dark times that we are living in, where state and fascist terror against non-white, non-european lives seems to only be growing stronger and leading to more misery and death. But amidst all the terror, there is also resistance and openings of revolt. The laws, borders and controls of Fortress Europe are being refused, fought across and challenged every day. As the consequences of global capitalist war come home to Europe, in the border riots, hunger-strikes and battles against police, it seems like a spirit of revolt is coming with it (perhaps a continuation of the revolts of the Arab Spring). Where the mainstream media sees a “refugee crisis”, we can speak of state-fascism, and when it tries to paint a picture of either “migrant swarms coming to Europe” or helpless brown and black others in need of western charity, we can plot how to be accomplices in solidarity with the revolt currently underway against borders and racism.

There are urgently-needed forms of support and ways to be active along the refugee route as anti-authoritarian and autonomous groups. This can a lot of the time mean providing basic necessities (food, water, blankets) and assistance to the hundreds of thousands people currently on the receiving end of the darker sides of capitalism, and bringing solidarity to where the state and charity organizations are bringing racism, violence and neglect. But all along the way spaces exist and can be opened up where solidarity for survival meets solidarity in resistance.

This text is based on one week with an autonomous-kitchen crew at the Serbian-Croatian border, where, in that week alone, 100 000 people crossed into Croatia through two border crossings within a few km of each other, in continuous arrival. With a mobile kitchen and a convoy of cars, we cooked and distributed food and water and clothes (many people hadn´t eaten or slept in days and were dressed for warm weather), assisted people in any way we could in both calmer and dire emergency situations, and also got to know a bunch of people who´s practices of mutual support, and resolve and strength despite the circumstances, was inspiring.

We first set up our kitchen on the Serbian side of the border, before moving to outside the prison-camp at Opatovac, on the Croatian side, where those who crossed the border were taken to by bus, or made to walk the 15km to the camp. Here sometimes up to a thousand people would end up stuck outside waiting to get in and set up a spontaneous encampment outside, which at first the police would try to prevent from occurring, by going around shouting at and shining flashlights at exhausted people sleeping on the ground or setting up their tents, but would quickly give up when they became overwhelmed by the numbers arriving. The state being overwhelmed by numbers is something that can be noticed from the on-the-ground policing of individuals at borders, to the unravelling political crisis between European governments. At times it simply breaks down the EU´s and the nation state´s ability to police, block entry and deport.

The camp was isolated in the country-side with only small towns some km away. People were brought here by bus or walked, forcefully directed along the road by the police. The area surrounding the camp was patrolled by police who would send people back if they tried to get away. From here, after 2-5 days stuck inside buses would drive people to the next border of Hungary or Slovenia, and drop them there.

The border zone where we were located forms part of what is being called a “human corridor”. At the the time of writing this exists as an always changing and chaotic route (basically due to different states battling each other over not wanting to have to take in and deal with refugees) where from Greece to the Austrian border people are making their own way (often by foot) and are getting shuffled by each state, by bus and train, which involves being held-up in prison-camps along the way, and being held at or totally blocked from crossing borders. The “human corridor” is more like an obstacle course of violence and imprisonment.

This is how it worked at the Serbian-Croatian border crossings at Sid and Babska: buses would arrive bringing people from the Macedonian-Serbian border further south and drop them some km before the border. They were then made to walk through fields, rather than down the road which held the border stations, in order to arrive directly in the no-mans land between the Serbian and Croatian borders and therefore by-pass the fact that Serbia was letting them out of state borders uncontrolled. From here buses would arrive infrequently to take people to the camp at Opatovac. To the press it was told that the camp served to provide food and shelter to people. In reality it was an over-crowded prison without food and where people slept on the ground, and often out in the open when the military tents were full. It was also a state attempt to control the flow of people, restrict their freedom of movement, isolate them, and channel them into the camp and out of the world´s sight, and out of the country as fast as possible. Because the buses would only arrive infrequently, and a continuous flow of sometimes up to 10 000 would arrive here every day, thousands of people would build up in the no-mans land. Our kitchen and another group giving out cold food were the only ones providing food where people would get stuck for days out in the open.

Taking control of the situation themselves, the people waiting organized themselves into groups for each bus. With the bus-group numbers going into the 200s, people knew they would be there for days. This situation seemed pretty dire, but after getting to the “refugee camp”, this spontaneous encampment seemed relatively ok. Although hungry and cold, people were in good spirits, probably relieved and happy to have finally arrived in the Schengen zone, thinking that this equated to reaching some kind of safety. It was warm during the day, hadn´t begun to rain yet, and people were also able to get warm food from the DIY kitchens and make fires at night.

The camp at Opatovac is a former military camp, hastily constructed into a refugee prison and surrounded by high fences. It was run by the military and police, with some minimal Red Cross, Unicef and UNHCR presence, who basically were just assisting the cops. It held military tents for sleeping, some medical tents, some toilets and that was about it. People slept on the ground and blanket and water distribution by the Red Cross was rare. Several times I would see groups of Red Cross workers standing around smoking next to piles of blankets or water, when I told them that the people inside were desperate for these things they would make some excuse about why they weren’t distributing them. “They will only be here for a few hours and will make the blankets dirty”. People were stuck here for days. “They have access to water inside”. People were made to queue for many hours in order to move into the next zone in the camp, and couldn’t leave these queues to access the water supply.

In the days I was there, I saw food being distributed once by the Red Cross (bananas and tins of fish). I heard that in another camp they stopped distributing the tins of fish because people were throwing them at the police. The camp had a capacity for approx. 3000 people, but sometimes would be holding up to 5000 people, with many setting up camp outside as well. If people wanted to get on one of the buses taking them to the next border, they were forced to go through this camp. After being dropped here in buses and crammed into police vans normally used for arrestees, the police would direct them into the queue to get into the camp, and stop them from trying to make their own way.

These are some of my impressions from the camp: crowds crammed together behind fences in the heat at the exit waiting all day to get out and get on buses. People passing out in the heat. The crowd growing angry at being held for so long. The cops tear-gassing people in response. Children getting injured from tear-gas. Cops smirking in the faces of a young distraught couple who they were not letting through to another zone in the camp in order to try and find their family from whom they had been separated. A cop hitting a young boy. The many sick and injured people not getting medical attention.

So basically: over-crowded conditions, regular police brutality, lack of provision of basic necessities such as food, water, blankets and medical attention. A really shitty prison. It couldn´t be being made clearer both that what makes a criminal a criminal is that society defines and polices you as such, and that some are made criminals because of the colour of their skin.

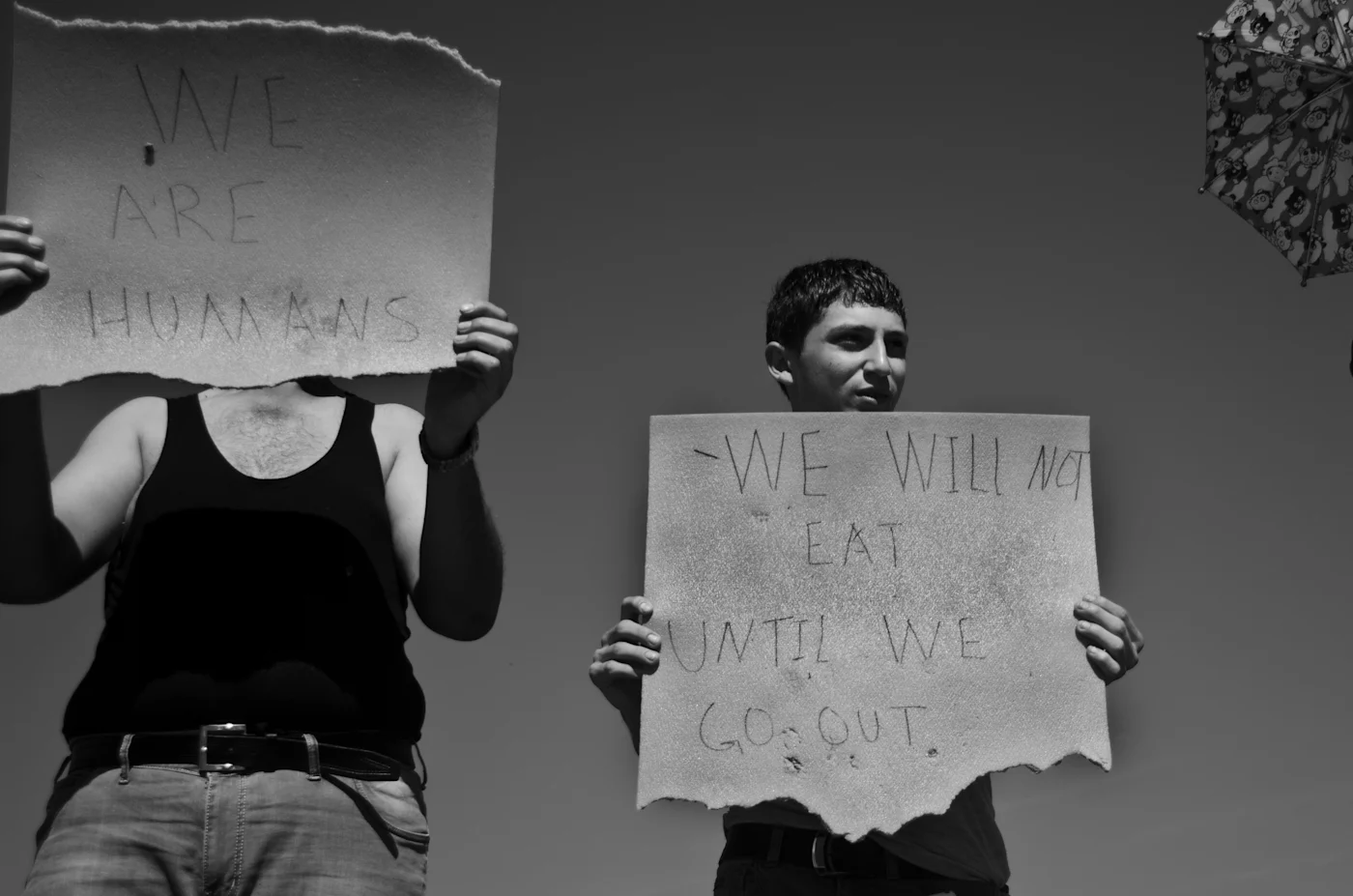

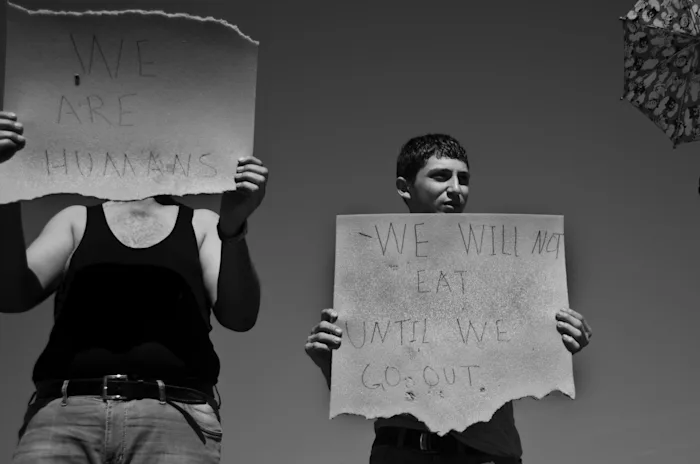

Whereas in the no-mans land at the border, people were tired but generally doing ok, the camp served to imprison, exert violence, break people down, separate families and leave people hungry and cold. But there was resistance. The following images show a group of men who organized a protest against their imprisonment and went on hunger-strike. The stood on a hill to try and be visible from outside the camp and held up signs written on torn up sleeping mats which said the following: “WE ARE HUMANS NOT ANIMALS”, “WE WANT FREEDOM” “WE HAVE BEEN ARRESTED FOR 4 DAYS”, “BAD TREATEMENT”, “THE POLICE THE SAME AS ISIS”, “NO FOOD NO WATER JUST LET US GO OUT”, “WHERE IS EUROPE!!!”. In addition people would try and push against the police fences holding them in, and throw things at the police.

Outside supporters like people from our kitchen crew managed to get inside the camp and before we knew it we were in the strange position of being the main providers of basic supplies to people inside. People were very very hungry. After setting up our kitchen immediately outside the camp and giving food to people who were standing for hours in queues waiting to get in, we began to take food and water to the perimeter fences of the camp where people were waiting for the buses to get out. Then we began jumping over the fences to take food in. Then we tried just walking in. I think the combination of the chaos of the situation and having high-visibility vests to make us look official is what allowed us to get inside and continue to get in for days. From my perspective, this quickly became an ambiguous situation. On the one hand it was good that we could bring basic supplies in and get food to people who hadn´t eaten in days. But on the other hand it was uncomfortable to suddenly be working within the camp structure, in the role of providing basic human assistance inside a prison-camp, and in some way easing the situation for the charities and the cops in their miserable combination of overwhelmed and neglectful/racist prison guards.

But besides getting food and water to people, our presence within the camp had other advantages: we could access the different zones where camp-inmates were not allowed to move between and so could try and help families find each other, we could try and get help for those needing urgent medical attention, we could speak to people and check on how they were doing, and for example when a cop tells you not to give out oranges because the imprisoned are throwing them at the cops, well you know what to bring a lot of into the camp… Also, no press was allowed inside the camp, so we were able to get images showing the horrible reality behind the manicured press shots of the interior minister of Croatia walking around shaking people´s hands in the orderly and clean looking front area of the camp that was visible to press from outside.

One night a build-up of several thousand people occurred at the border 17km away. The people there grew frustrated at being forced to wait for hours for buses, out in the open in the cold, and began to try and push through. As punishment for this, the cops stopped bringing buses altogether and told people they had to walk. Hearing about this, a group of supporters went out with food and a few cars to transport people. When I got to the scene, maybe 5km into people´s walk, it had started to rain. Groups of several hundred people started to appear walking towards us on the road. The groups of younger men (traveling groups seemed to be either family groups or groups of men) were doing alright, and just wanted to keep going. The families; the people carrying small babies; the young children; the elderly people; the people with injuries, were exhausted and struggling. Most hadn’t slept in several days, and the only real food they were getting was what a scattering of DIY kitchens were able to provide along the way. When exhausted people sat at the spot we were giving food and water and what rides we could with a few cars, cops would come and shout at the people to get up and keep walking. Every 30 mins or so, one small cop van would come to take some of the women and children, always being aggressive, shouting at people in Croatian, and shouting at the men that they couldn’t get in the vans with their families and had to walk.

Of all the horrible shit I saw happen that week, the separating of families was the worst. Families traveling together seemed to form very strong support networks. At this point eachother is all they have. Many of the walkers didn’t know where they were or that they were being forced into the transit camp. Before entering the camp some were able to find each other again, but many didn’t, and once inside it was difficult, as people were separated into different zones.

I met people who were in a whole range of states that week: determined and unstoppable; happy and relieved to have reached europe; people singing together under tarps in the rain as they waited; people singing and playing drums inside the camp; families laughing together as they set up their tents. To see such forms of collectively and lightness within this dire situation was inspiring. But there were also people who it was clear had been through too much; had been pushed too far: shell-shocked looking kids, an exhausted woman unable to walk further, trying to comfort her crying baby in the rain by the side of the road. And on top of the many people with serious injuries and life-threatening conditions, again and again the people who were in the worst states psychologically were those who had been separated from their families at the camp or along the way and didn´t know where they were. Like the woman I found sitting in the Red Cross “family re-unification” tent (just a tent where people who had lost their families were left), rocking back and forth and wailing in desperation, while her young daughter tried to comfort her. Neither her daughter, nor the other woman sitting there waiting to find her family, nor I could get through to her. Separating families is one of the many destructive things the state was doing here, as their togetherness and bonds seemed to be the key basis for their survival and capacity to endure through all this shit.

Although they were clearly overwhelmed by the numbers of people, it was also obvious that the work of the charities and NGOs present (the Red Cross and the UNHCR) amounted to cop-assistance and collaboration. On the fourth day or so of the time I was at the camp, the Red Cross boss of Croatia arrived and was “shocked” by the conditions. After the red cross workers present had already cut off our kitchen’s water supply, and at the same as civil cops began controlling our papers and threatening to kick out all the solidarity structures present outside the camp, the Red Cross boss told us to come to him if there were any supplies we needed. Eventually, on day 5 or so, the kitchen was made to leave the camp by the military. It tried to follow the buses which were transporting people to the Croatian-Hungarian border, but was stopped by the police along the way and forbidden to go there. It is clear that the state wants people to remain isolated, and will repress autonomous support and solidarity.

There are some clear causes to this situation: global capitalism, centuries of colonialism and Western imperialism, the West’s instigation of and involvement in wars in the Middle East and Africa in it´s attempt to gain control over resources, regional conflict, racist asylum polices, racist borders, rising islamaphobia and fascism. We can also identify clear consequences: death, misery, and suffering. It is hard however to see an end to the misery and trauma. People are fleeing the atrocities of war and when they finally arrive on European shores, instead of finding some basic safety, of endurance being that much more possible, they find governments who criminalize them and are unable to coordinate an adequate political and humanitarian response, they find profiteering smugglers who give zero shits if they live or die, they are left in the hands if violent fascist thugs in uniforms, they find camps which, in the refugees´ own words, are prisons where they are treated like animals. The misery doesn’t end after the 17 km walk at night in the rain to the camp. It doesn’t end when they arrive at the camp, and it doesn’t end when they finally get on a bus to the next border. And nor does it end when they arrive in Germany or Austria, where asylum laws have just been tightened, the deportation machinery strengthened, and where nazi attacks on asylum seekers and their homes are increasingly frequent and vicious.

Did I mention that the cops running the camp were dressed in full riot gear? And that the military was also present there? These were the people left in charge of refugees fleeing from soldiers, ISIS, bombs and war… Who are coming to Europe not because they necessarily want to be here, but because they are fleeing from death. Who have already been living through very terrible shit, and many of whom are injured and traumatized. Young hungry and exhausted children with Post-Traumatic-Stress Disorder.

Europe, you vortex of putrid civilization.

The misery ends when the world as it exists now ends. When it is destroyed. The misery ends when we destroy the world as it exists now. Refugees are already leading a revolt against borders and state violence, and there are many ways to be their accomplices in this struggle.

“There is no need to fear or hope, only to look for new weapons”

Some practical ways to support those coming to europe in their struggle across and against borders could include:

Providing for basic human needs: warm food, shelter, water, medicine, warm clothes, tents, waterproofs, food and supplies for young children and babies.

Providing people with things that could help them be autonomous on their journeys and by-pass the states controls, borders, and camps, and empowering people through spreading information. For example: maps of the local area and of europe, info on where they can get buses and trains from, information on current border situation that are ahead of them and the safest routes to travel, telephones with local sim cards and internet, setting up phone charging stations and free-wifi hotspots along the route.

Driving people across borders and to where the want to go: this website fluchthelfer.in provides legal information and legal and financial aid to those who can drive people. It is considered illegal (“aiding and abetting illegal entry”, but it says that within Europe at least, prosecution is rare.

Supporting resistance against the police.

The state will try and break (anti)political forms of solidarity and support and work to continue to isolate and confine non-citizens. We will not let this happen.

—Anonymous Berlin, late September 2015

Photographs by Hendrick Hassel, except for riot photo.