Mapping the Left in China

Ralf Ruckus

Is China still socialist? Is the Chinese Communist Party a left-wing organization? Are its leaders even Marxists? In a new book, Ralf Ruckus maps the CCP’s political development from the 1950s to the present.

Ruckus has been studying the social, economic, and political situation in the People’s Republic of China for almost twenty years. He is a founding member of the gongchao collective, which documents social unrest and movements in China. In his 2021 book, The Communist Road to Capitalism, he shows how, since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, class conflicts and other social struggles have been met by countermeasures of the CCP regime which sought to secure its rule. This dialectic between struggles and countermeasures functioned as the driving force of China’s historical development. His newest book, The Left in China: A Political Cartography (2023), continues this work, focusing instead on the specific dialectic of social struggles and left-wing circles. Throughout the three recent periods in China (socialist, transitional, and capitalist), changing conditions triggered social protests and upheavals, and these protests and upheavals produced and inspired different oppositional left-wing groups or movements. By shifting our attention away from revolutionary rhetoric of the CCP and toward these oppositional movements of Chinese workers, peasants, students, and women, Ruckus makes clear that the Chinese Communist Party has long been an anti-left-wing force.

How, then, can we explain the confusion on this point among so many leftists outside of China? It is to this question that the following two excerpts are addressed.

The CCP’s Anti-leftist record

This book’s focus lies on oppositional left-wing tendencies, social movements from below with left-wing demands, practices, and perspectives, or political groups or currents with left-wing agendas. The positions of the CCP, its leaderships, and its changing frictions and factions appear here and there in the narrative, but deserve more attention than could be given in this book. In this section, I confine myself to addressing one characteristic of CCP policies in the past decades: the attitude of the party leaderships towards left-wing opposition.

The CCP changed from a leftist force during the socialist period and the early transitional period to a rightist force during the late transitional and the capitalist period. Still, several elements defined the party’s rule over all the past decades and have survived historical shifts and changes: first, the aim of economic development and expansion through industrialization and infrastructure construction (development, productivism); second, the promotion of the interests of the country in the world-system (nationalism); third, one-party rule as the condition for accomplishing development goals (authoritarianism); fourth, the strategy to weaken, repress, or co-opt powerful (left-wing) opposition from below (anti-leftism).

I will focus on the last point here. In the socialist period, the CCP used Maoism, an adapted form of Marxism-Leninism, to explain and justify its economic, political, and social course. This included rhetoric of class struggle and revolution. The CCP leadership defined the political line all other parts of society were supposed to follow — and it defined what it saw as deviation(s). Mao Zedong himself used the left/right spectrum in this respect in a 1955 speech before the Central Committee: “When the right time comes for something to be done, it has to be done. If you don’t allow it, that is a Right deviation. If the right time has not come for something and yet you try to force it through, that is a ‘left’ deviation.”1

It seems obvious that the CCP regime, with its revolutionary roots and socialist rhetoric, tried to deal with right deviation (of monarchists, KMT, or capitalist forces) during the socialist and the transitional period. Immediately after 1949, some of these forces were still quite strong, but after several anti-rightist purges in the early 1950s, and especially after the Anti-Rightist Campaign in 1957, most of them were severely weakened or exterminated.

Leftist forces inspired by social discontent or upheavals, however, persisted... The CCP leaderships reacted with repeated anti-leftist campaigns and purges as left-wing critique and opposition are seen by the CCP leaders as undermining the party’s legitimacy and rule (more than any re-emerging right-wing opposition). This began with conflicts on the party line and anti-leftist party cleansing purges in the 1940s and continued with crackdowns on strike waves and leftist critique around the Hundred Flowers Movement in the mid-1950s, attacks on the “economist wind” and left-wing rebels or Maoist dissidents during the Cultural Revolution in the second half of the 1960s, repression of movements for a democratic socialism in the mid- and late 1970s, the anti-leftist campaign in the second half of the 1970s formally against the Gang of Four, the crackdown against the workers’ protests during the Tian’anmen Square Movement in 1989, the repression of various generations of Maoist grassroots activism, and attacks on left-wing grassroots labor activists and feminist activists in every decade since the 1990s.

The CCP leadership also changed its self-presentation and legitimizing strategy. During the socialist period, it merged two lines or political positions that were both necessary parts of the CCP’s socialist project and its Marxist-Leninist-Maoist agenda: a developmental line focusing on socialist modernization and a mobilizational line focusing on social engineering and ideological guidance. At times, those who represented these lines harmonized in the attempt to build up socialism, at other times they merely coexisted to avoid conflict, and sometimes they openly competed, as after the GLF or during and after the Cultural Revolution. From the 1960s on, the CCP used the description of left and right (or variations of it) when referring to this antagonism or dialectic between the “right-wing” developmental line, for instance of the “capitalist roaders” Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping and the “left-wing” mobilizational line of Mao Zedong or the “ultra-left” faction and Gang of Four.

In the 1980s, that is, after the socialist period, the CCP leadership gave up using revolutionary or class struggle rhetoric. Economic development without social liberation or revolution became the main goal. In the 1990s, the CCP finally dismantled the socialist planned economy, and in the early 2000s, under party leader Jiang Zemin, it formally allowed capitalists to join its ranks. Socialism in the PRC form, which had already failed to accomplish revolution in the first place, was thereby further de-revolutionized. For many observers, “left” now stood for the “conservative” part of the leadership, that is, cadres who hung on to the socialist model and were reluctant to support the market reforms.

However, the CCP has still been promoting its own version of (what it calls) socialism. On the one hand, it wants to claim the historical “success” of “national liberation,” utilize the symbolic value of party founder, leader, and icon Mao Zedong, and justify its description as a “communist party.” On the other hand, the party’s legitimacy is built upon socialist narratives of “serving the people” or “welfare for all” — or, at least, the myth that everyone will eventually benefit from the economic rise of the country. This is what makes left deviation or left-wing oppositional critique potentially explosive. Social or political issues raised by workers, peasants, women*, or leftist activists threaten the plausibility of the CCP’s definition of socialism.

[A]s long as “socialism” remains symbolically important for the party’s political legitimacy, the CCP has to bear the burden of justifying its current practices in socialist terms, which will therefore involve a protracted ideological battle with the leftists over what is authentic socialism and who represents it.2

That ideological battle is fought on several fronts. First, since the 1990s, scholars at party schools and universities discuss and develop an adapted form of Marxism that is stripped of its subversive elements and presented as a science of how to run a (“market socialist”) economy. In practice, what the CCP promotes is the control of capitalist forces by the state and a quasi-Keynesian version of welfare policies (anti-poverty, “common prosperity”) that pretends to aim at wealth distribution but, in reality, does not touch the structural conditions for exploitation and social inequality.3

Second, in the past two decades, the socialist narratives of welfare and development have been maintained but also complemented, for instance by Confucian concepts and references to China’s imperial history and legacy. The CCP adds to all its political and ideological terms, including its domesticated Marxism, the notorious “with Chinese characteristics” (zhongguo tese). Its references to Confucianism and imperial tradition enabled it to create a “Western” (hostile, dangerous) “other” versus the (good, benevolent) “Chinese.” It makes use of Confucianism and (alleged) imperial tradition to stress the central role of the state or obedience to the rulers, and CCP policies even imply the superiority of the Han (the dominant ethnic group) vs “minorities” as the Uyghurs and other Muslim groups in Xinjiang.4

Third, since the 2000s, the party has re-emphasized its adapted (and depoliticized) Marxism. Local CCP leader Bo Xilai used Maoist folklore, anti-corruption rhetoric, and limited welfare measures for the so-called Chongqing Model in the late 2000s, winning support from leftists loyal to the CCP. As mentioned in the previous chapter, Bo was seen as competition for the then would-be party leader Xi Jinping and was eventually disempowered and arrested for corruption in 2012. However, the new party leadership under Xi Jinping learned from his methods and also began referencing Marxism and Maoist symbolism more. The CCP still invests energy and resources in Marxist scholarship and ideology to legitimize its rule. That earns it the support of certain loyalist leftists, for instance, from the New Left, or other actors who sympathize with certain egalitarian leftist ideas while defending authoritarian party rule.5 In some cases, this includes pressuring, attacking, censoring, and silencing people who oppose or simply do not follow the official party line.6

Lessons for Left-wing Strategies

The CCP was part of the left-wing (revolutionary) movement in China in the 1920s, and today’s left (in the PRC and elsewhere) has to deal with the CCP’s leftist legacy, as well as that of other political forces that came out of left-wing revolutionary movements before establishing different versions of actually existing socialism. However, these Communist Party regimes should be measured according to their political record (and not their pseudo-radical or pseudo-Marxist rhetoric, for instance).

For decades, the CCP has been an anti-leftist force or, more precisely, a force against left-collective and left-egalitarian ideas and practices. It has undermined and repressed social struggles and oppositional left-wing movements in the socialist period and ever since, as we have seen in the chapters of this book. Social conflicts and struggles in the PRC continue. While the country has intensified its economic and political engagement around the world, leftists should make up their mind and take a stand. Today’s CCP is no ally in the struggle against capitalist exploitation, racism, gender discrimination, nationalism, imperialism, and environmental destruction.

The left in the PRC and elsewhere needs to find an answer to the global confrontation between what is presented as China vs U.S., Chinese socialism vs universalist Western capitalism, or authoritarianism vs liberal democracy. This presumed dichotomy serves both Western governments and the CCP regime. In reality, we see interconnected powers of capitalist exploitation with a more or less authoritarian governmental structure. Despite many differences, the political forces in power in the U.S., in European Union states, in the PRC, and in other countries all oppose left-wing movements demanding an end to capitalism, patriarchy, nationalism, imperialism, and more.

Realizing the egalitarian redistribution of wealth and power globally can hardly be accomplished without a revolution in the PRC and in the rest of the world. Currently, we are not seeing a revolutionary moment in the PRC, a moment in which such an egalitarian redistribution could be won. When such a moment emerges again, the revolution needs to be orchestrated by social actors from below. The experience of the CCP (and similar parties behind actually existing socialisms) teaches us that the revolutionary transformation of a society by a privileged class and its party in power is not just “a contradiction in terms” but simply no viable way to overcome exploitation, patriarchy, and authoritarian rule.7

What role can today’s left in the PRC play? The loyalist leftists (or Maoist Right) in or close to the CCP will not get involved in social unrest or organizing that is openly oppositional. The New Left intellectuals will not “leave the ivory tower and appeal to the masses directly.”8 Many of them have supported PRC nationalism or even the regime under Xi Jinping after 2012.9 That leaves the oppositional left, and mainly left-wing feminists and various currents of the Maoist Left. We will have to see whether feminists will attack both the structural gender discrimination and violence against women* and the capitalist structures and practices that define the CCP regime. Maoists have persistently invoked Cultural Revolution rhetoric, engaged in more confrontational debates and criticisms of the market reforms, and some of them were involved in the actual struggles of state workers (and later migrant workers). However, some of them are nationalist and statist, and most of them still believe in the Marxist-Leninist narrative that a vanguard party, democratic centralism, and the dictatorship of the proletariat are necessary to carry out a revolution — a recipe that has failed. Meanwhile, most other left-wing currents are too small to exert any substantial influence.

In addition, the CCP regime and its repressive forces are currently too strong, and the oppositional left is too weak for it to play a bigger role in PRC politics. Even the question of whether there is a left-wing alternative is not discussed much with regard to the PRC, not only because the CCP holds onto its self-description as socialist, but also because the party has successfully prevented any leftist structure or group from developing enough strength even to be considered an alternative. The oppositional left in the PRC seems to face a difficult time, particularly when we consider the intensified repression and the arsenal of tools the CCP regime uses to counter discontent and protest. Most of the Maoist Left activists are keeping a low profile and avoid publicly supporting social struggles or engaging in political debates on online platforms controlled by the state.

However, if there is any hope for fundamental change in the PRC for the better, the overcoming of capitalist exploitation, patriarchy, and social discrimination, it has to come through struggles of workers, peasants, migrants, and women*. The left could use such struggles to recompose and reinvent itself, overcome the socialist (or Cultural Revolution) nostalgia, and formulate a new left-wing strategy that goes beyond nationalism or national liberation and socialism.10

The chances for larger and more powerful social protests are not that small. The regime’s situation is not as stable as it might appear (especially in fashionable leftist accounts of the CCP’s almightiness, its technological potency, and its allegedly crisis-proof economic strategy): the economy is crisis-prone, the state’s surveillance is less potent than described, the central state has difficulties controlling lower state levels, and environmental crises loom.11 Social discontent continues, labor shortages could further increase workers’ bargaining power, women*’s struggles could lead to more empowerment, and the harsh repression of protests in the past few years indicates that the regime might lose its capability of responding flexibly to social discontent.

Throughout PRC history, social movements from below have proven that, in certain moments, they are capable of collective action and cross-regional coordination, even without any complex organizational nexus. As the CCP leadership and the state combine economic and political power, they take on the responsibility for anything that goes wrong, and every protest potentially becomes a protest “against the government.”12 If the regime’s tools to defuse or repress such movements do not work, then these movements could, indeed, change history.

What does all of this mean for the left outside of China? Similarly to Maoists in the PRC, Maoists outside the PRC need to overcome their Cultural Revolution nostalgia and find a new leftist strategy beyond national liberation and authoritarian socialism. Regarding the current CCP regime, they and other leftists need to get a clear view of what is going on and then decide on which side of the barricade they want to be. In effect, the CCP uses a socialist or leftist costume to cover up the same capitalist, nationalist, racist, and patriarchal policies that characterize any rightist regime. Some leftists understand this, yet still endorse the CCP’s rightist policies; they should be called out for that. Other leftists still fall for the costuming, or simply do not know enough about the PRC’s past and present and the transformations of the CCP. This book is meant to provide the necessary information and analysis for them to make up their mind.

Ultimately, the question is whether the global left wants to hang onto authoritarian leftist strategies and support the exploitative CCP regime in its attempt to expand its global influence. If, by contrast, the plan is still to overcome capitalism and patriarchy globally, then the tasks are clear: follow and support the social struggles of workers, peasants, migrants, and women* in the PRC, connect to the oppositional left there and defend them against the attacks of the rightist regime.

The Left in China. A Political Cartography (2023) is now available with Pluto Press.

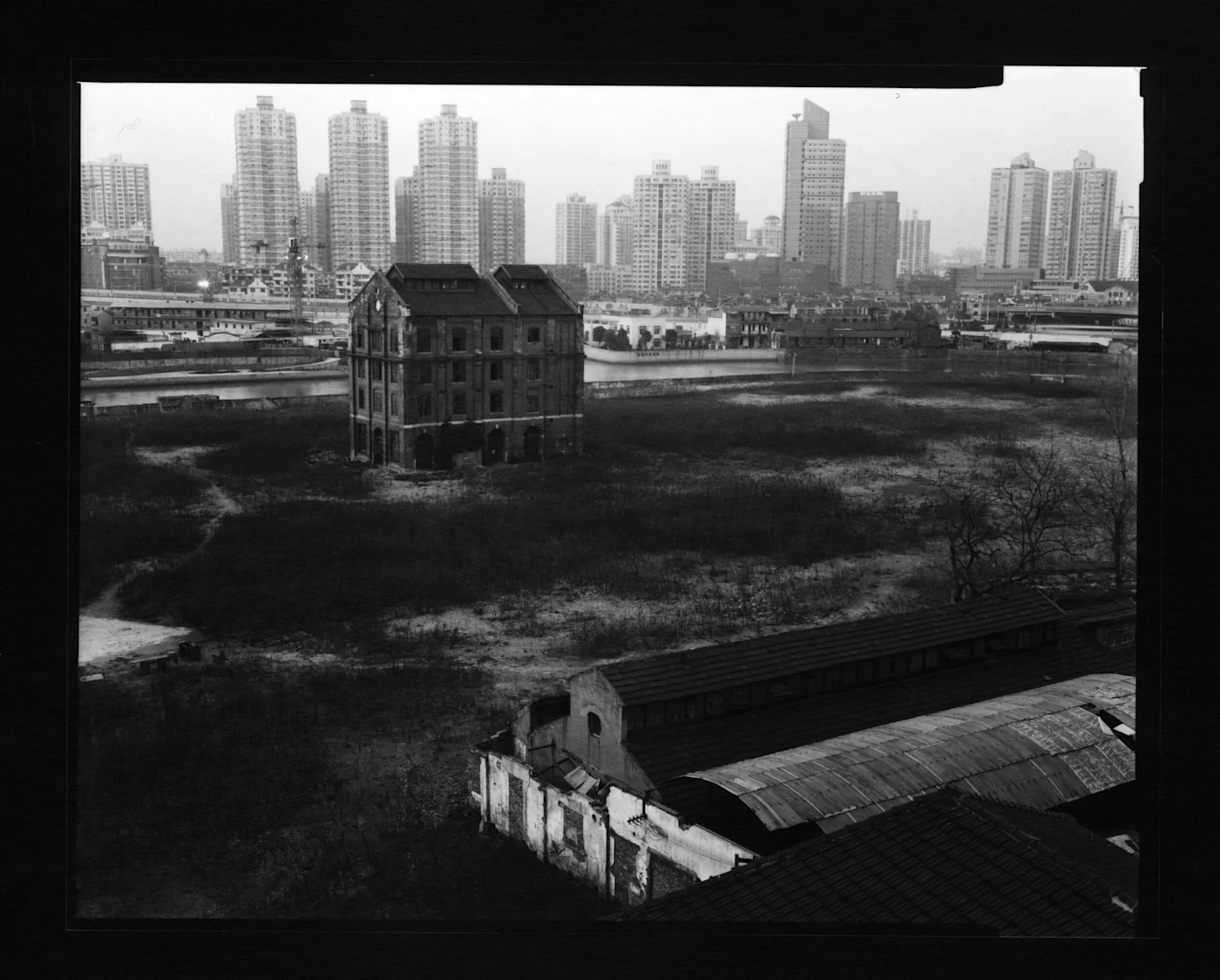

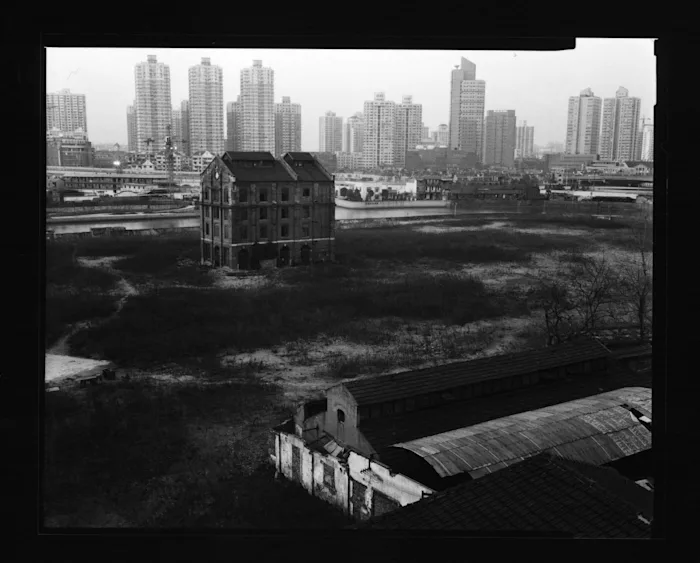

Images: Bogdan Konopka

Notes

1. Mao Tse-Tung, “The Debate on the Co-operative Transformation of Agriculture and the Current Class Struggle (October 11, 1955),” in Selected Works of Mao TseTung, vol. 5, Pergamon Press, 1977, 230–231.↰

2. Chen Feng, “An Unfinished Battle in China: The Leftist Criticism of the Reform and the Third Thought Emancipation.” The China Quarterly 158 (1999), 466.↰

3. When, in 2021, the CCP regime under Xi Jinping began to promote “common prosperity” (gongtong fuyu) and call on private companies to contribute to society, commentators saw this as a sign of the socialist orientation of the regime. In reality, the CCP is promoting the limited redistribution of wealth in order to maintain social stability. Its programs of poverty relief or other welfare measures are part of quasi-Keynesian policies. See Ralf Ruckus, “Leitplanken für den Kapitalismus.” WOZ, September 9, 2021. Online here.↰

4. There are further influences not discussed here, like neoconservatism. Its propositions have “been crucial as theoretical fuel for the development of CCP ideology over the last three decades. The elevation of a former neo-conservative intellectual, Wang Huning, to the Standing Committee of the Politburo, the highest body of the CCP, in 2017, is an indication of its lasting impact on successive leadership generations. Indeed, the articulation of the ‘Chinese Dream’ under Xi Jinping can be viewed as an amalgamate of a neo-Confucian appeal for meritocratic elite governance and a neo-Conservative defense of ‘authoritarian modernity’.” Andreas Møller Mulvad, “China’s Ideological Spectrum: A Two-dimensional Model of Elite Intellectuals’ Visions,” Theory and Society, vol. 47 [2018], 645.↰

5. The CCP’s political intervention and monetary investment in Marxist scholarship also earns it the support of parts of the left in other corners of the world.↰

6. Those who do not follow the official line also face online attacks by CCP supporters such as those called Little Pink (xiaofenhong; young volunteers active, for instance, on Twitter or Instagram, who attack people who criticize the CCP regime) or the 50 Cent Army (wumao dang; online commentators paid by the state who support the CCP regime); see Fang Kecheng and Maria Repnikova, “Demystifying ‘Little Pink’: The Creation and Evolution of a Gendered Label for Nationalistic Activists in China.” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 6 (2018), 2062–2086; Han Rongbin, “Defending the Authoritarian Regime Online: China’s ‘Voluntary Fifty-cent Army,’” The China Quarterly 224 (2015), 1006–1025; and Jason Y. Wu, “Categorical Confusion: Ideological Labels in China.” Political Research Quarterly, September 9, 2020, 8. Online here.↰

7. Arif Dirlik, “Back to the Future: Contemporary China in the Perspective of Its Past, Circa 1980,” in Wang Ban and Lu Jie, eds., China and New Left Visions: Political and Cultural Interventions, Lexington Books, 2012, 18.↰

8. Cheng Yinghong, “Che Guevara: Dramatizing China’s Divided Intelligentsia at the Turn of the Century.” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, vol. 15, no. 2 (Fall 2003), 27.↰

9. To be more precise, backing Chinese nationalism or the current CCP regime does not just mean endorsing the CCP’s authoritarian policies in the PRC, including its neocolonial strategy in Xinjiang, but also its expansionist or even imperialist strategy globally, and its support for capitalist and authoritarian regimes in other parts of the world.↰

10. For a list of key aspects of left-wing politics and a list of elements for a left-wing strategy, see Ralf Ruckus, The Communist Road to Capitalism: How Social Unrest and Containment Have Pushed China’s (R)evolution since 1949,, PM Press, Conclusion, third section.↰

11. For a more detailed argument on the potential instability of the CCP regime, see Ruckus, The Communist Road, 173ff. ↰

12. Manfred Elfstrom, Workers and Change in China: Resistance, Repression, Responsiveness, Cambridge University Press, 2021, 161.↰