Political Conditions for a New World Order

Maurizio Lazzarato

What function does war, robbery, and violence play in the reproduction of capitalist society? In this companion piece to his October 2024 essay, "Why War?," Maurizio Lazzarato argues that Marxist and Foucaultian interpretations of production and biopower have unjustly downplayed the constitutive role played by civil wars, coups d'état, and class struggle in political life, resulting in a pacified conception of the social order. By synthesizing Karl Marx’s analysis of “primitive accumulation” with Carl Schmitt’s account of the state of exception, Lazzarato argues that a “political death” of the vanquished precedes the stabilization of all new political-economic orders. This insight casts new light on our present moment: just as, in the 1970s, it was the state that “violently forced the transition from one political-economic order to another” through the use of force, Lazzarato predicts that the current outbreak of global war will result in a new regime of private property that “no longer places producers at its center, but the owners of stocks, bonds, and financial assets.”

Other languages: Italiano, Türkçe, العربية, Ελληνικά, Français

Teacher: "Reflect, child, where these gifts come from. You can have nothing from yourself." Child: "I got everything from father." Master: "And where does he get them from?" Child: "From grandfather." Master: "But no. And who did grandfather get them from?" Child: "He took them." —Marx, Capital

Our current political impotence is the direct consequence of the exclusion of war and civil wars from critical theory, which is itself the result of another exclusion, namely, that of class struggle, that is, of revolution. To pose the problem of war is today to pose the problem of the world market.

Whenever war, civil war, genocide, and fascism loudly resurface in the headlines (and with them, paradoxically, the impossible possibility of revolution) we find ourselves powerless because, although they are an obvious result of capitalist production, they are nevertheless inexplicable in terms of the categories supplied by the critique of political economy. What relation do wars have to capitalism and its production? Do they constitute accidents of its development, or structural elements? And furthermore: what relationship exists between the state, which has the power to declare and manage war, and capital? Can a concept of production that marginalizes the state and its sovereignty still be valid? Can we continue to regard the latter as merely functional and subordinate to the needs of capital accumulation?

In our previous article, we saw how the assertion of U.S. sovereignty went hand in hand with a role that we hastily defined as the subordination of the state to finance. In reality, sovereign power, which finds its highest expression in war, cannot manifest itself without the power of finance, and the latter's economic monopoly cannot subsist without the politico-military monopoly of force that promotes and imposes dollarization, an indispensable condition for the existence of both the American state and finance. Economics and political power (and, I affirm once and for all, when I say political I also mean military) stand in mutual presupposition, but in phases such as the one we are going through, politics (and its military force) takes precedence, even if in the sovereign decision to wage war, the question of economic hegemony remains decisive. In our societies economic action and politico-military action are closely linked in that they form a single "state-capital machine," in which the former’s function is not merely instrumental and subordinate to the latter. State and capital pursue distinct but converging ends; the increase in power of the former and the increase in profit of the latter feed off each other.

It is not true that politics has disappeared, that the state has withdrawn; the state and politics are an integral part of the machine in which profit accumulation and power accumulation work together. The concepts and realities of power and the state have been the focus of critical theory from the 1960s to the present day. The goals it has pursued include a critique of the concept of sovereignty and a desire to overcome the Marxist interpretation that identifies power with production and reduces the state to a mere function of the processes of value accumulation.

By the end of the 1970s, Foucaultʼs concept of governmentality (the ensemble of disciplinary, biopolitical, controlling, and pastoral techniques) seemed to have achieved this goal: not only did it exhaust and marginalize sovereign power, but it claimed to contain the relations that explain the functioning of the mechanisms of power in contemporary societies, which it presented as irreducible to the action of both production and the state. Agamben, a few years later, corrects this theoretical and political pacification that eliminates sovereignty, by combining governmentality and sovereign power, biopower and state, but by making these categories trans-historical realities, invariants that traverse centuries while remaining unchanged. Both exclude capitalism, its dynamics, its contradictions, if only to adopt the “economic theology” of the Catholic Church fathers as an effective alternative to the critique of political economy (which is quite ridiculous), or to identify the workings of capitalism with the opening chapters of Marx's Capital, which Foucault briefly uses to explain the action of disciplines.

In short, my thesis is simple: the state and its sovereignty, the monopoly of force that manifests itself fully in war, but also its administrative power, should be integrated with Marxian concepts of capital and production. Let us try to explain more precisely this relationship, which eludes Foucault and Agamben and which, on the contrary, lies at the foundation of the present conjuncture. We can approach the problem by asking: how do we define the situation that was opened up by the financial crisis of 2007/2008? Its negative condition is given by the end of neoliberalism and the demise of its governmentality, which entails the subordination of disciplinary, biopolitical, and pastoral techniques to the needs of the war regime, which has the power to use them, suspend them, or simply suppress them.

That the economy can be regulated by the market and by competition, even if they are legally defined and activated by a state that intervenes with the same intensity and frequency as the Keynesian state, as the German ordoliberals maintain, has been the ideology — there is no other word for it — of the last forty years, to which much of critical thought has given credence by recognizing that the market and competition corresponded to something real. Fernand Braudel, who was not a Marxist, taught us that capitalism "has always been monopolistic," that competition serves to eliminate adversaries and that the market in capitalism does not exist, because it is a "counter-market" controlled by a few players which, precisely thanks to competition, always and inevitably leads to monopoly.

Braudel wrote that capitalists "have a thousand ways of distorting the game in their favor, through credit," currency, political power, etc. “Who could doubt that they have monopolies or simply the power to eliminate competition nine times out of ten?” Surely the ordoliberals, the neoliberals, Foucault, Dardot and Laval, all the disciples or admirers of the French philosopher, the media, politicians, etc., would.

How can we explain the fact that the end of neoliberal governance by the market has left us with the largest monopolistic concentration in the history of capitalism and the history of humanity? (see our previous article) Simply by fact that economic centralization (like political centralization) has never stopped. In fact, under neoliberalism it accelerated dramatically, masked by the ideology of the market and competition. Market and capitalism are not the same thing, Braudel tells us, and confusing them has caused and continues to cause immense confusion. To confuse capitalism with neoliberalism is a similarly gross error.

To grasp the contemporary situation, we need to take into account a tangle of events: financial crisis, populisms, new fascisms, civil wars, war, genocides. Giovanni Arrighi would describe this period as a "phase of hegemonic transition" or "systemic chaos." To be more precise, we could argue that the political phase opened by the 2007/2008 financial crisis, marking the end of "hegemonic cycles" (Braudel, Wallerstein, Arrighi), has the characteristics of Karl Marx's "primitive accumulation" and Carl Schmitt's "state of exception." So we have a "Karl und Carl" that’s different from Mario Tronti's, and a little more operational.

Two observations in this regard: in order to get a picture of capital and its relation to sovereignty, which plays a decisive role precisely during this period, we will start not from the beginning, but from the end of the first book of Capital, that is, from primitive accumulation. Marx described it as the epoch of the formation of classes and the (absolute) state within through the exercise of the great violence of wars, civil wars, wars of conquest and genocide. The German revolutionary mistakenly believed that, once capitalist production had asserted itself, it would reproduce its own conditions. This is either true in a limited way (it reproduces its conditions of existence in a specific mode of accumulation until that mode goes into crisis) or false, since the transition from one mode of accumulation to another, e.g., from Fordism to neoliberalism, did not arise spontaneously and immanently from Fordist production and consumption and the Keynesian state. The state-capital machine had to go through the organization of a rupture, a discontinuity represented by the 1969-1979 decade, which involved the intervention of sovereign power and armed force when necessary. It is the political, not just the state — in other words, war, coups d'état, revolutions, class struggle and their results — that decide the new configuration of capital relations, power relations, and the state form. The first division of labor is always political, not economic, because it must produce dominants and dominated, it must separate owners and non-owners. Private property is a presupposition of capital, an institution neither created nor guaranteed by capital itself, but instead by the state. The organization of production and the actual division of labor, as presented in Capital, emerge later to normalize the relations of power defined by the political struggles between classes.

The second observation concerns the concept of the state of exception, which allows for suspension of legal, productive and democratic norms, leaving the state, the use of force, and war to dominate and decide. However, contrary to Agamben’s view, the state of exception must be distinguished from the state of emergency. Bush's Patriot Act or the measures imposed by states during Covid are cases of emergency. We reserve the concept of a state of exception for periods of radical rupture marking the transition from one global economic and political order to another: the French Revolution marking the end of the Ancien Régime (feudal), the two World Wars, which were in reality one long global civil war, and, within these conflicts, the Soviet (or Chinese) revolutions which together defined a new world order (the Cold War). The 1970s marked the transition from Fordism to the ill-defined neoliberalism, just as the current situation heralds the end of the latter and the "new" that will emerge precisely from the current conflict.

Perhaps it would be more correct to adopt Schmitt’s concepts as a complement to primitive accumulation: the "nomos of the earth," a historical event in which conquest, war, and appropriation, like Marx’s primitive accumulation, generate and institute a new order and a new power. This event has no immediate need for norms, which will be instituted at a later date. Nomos is an event, a place and a moment of discontinuity where, through the exercise of force, the shape of the state, social classes, and relations of power are decided. Without primitive accumulation, i.e., without capital, the nomos of the earth would be purely politico-historical, when in fact, especially since the end of the 19th century but already since the French Revolution, it has become indissociably economic and political (a fact of which Schmitt is perfectly aware, seeing in the class struggle that has become irreducible since the rupture made between 1830 and 1848 the main reason for the end of the state as he desired it, i.e., an autonomous state independent of "society").

Law is not born in the zone of indifference between "inside and outside" brought about by the suspension of the legal system (Agamben), but out of conflicts between forces, where there are victors and vanquished. In no way, then, can the concentration camp be defined as the "nomos of the modern," its "hidden matrix," because, like the emergency, it is merely part of the strategies that destroy one order and bring about a new one. What becomes the rule, the daily management of power, is the emergency, not the nomos of the earth, which remains an exception. The pandemic does not define a new world order, but the war that broke out immediately after it does. Agamben became very agitated during the pandemic and practically disappeared during the war, precisely because he reduces the nomos of the earth to the problem of the suspension of the legal system. What we need to understand is that the “legal vacuum” of the state of exception is full of forces fighting for a new economic and political hegemony, or even, if possible, for an impossible revolution.

At the root of both primitive accumulation and the state of exception/nomos of the earth we find conquest, an act of taking possession that serves as both a source of power for the state and of profit for capital. It is through appropriation, through possession, that the state and capital communicate. Here Karl and Carl tell us that, before producing, we must take, appropriate, expropriate (land, human beings, resources, means of production, wealth, etc.) and divide what has been taken between owners and non-owners. Production does not create classes or the institution of property, nor is it capable of organizing the expropriation of the means of production and the resources needed to carry it out. On the contrary, it presupposes the act of taking, expropriating and dividing between owner and non-owners, between dominant and dominated. To exercise the great violence necessary for taking and dividing what becomes decisive is the use of force, war and civil war. Even before producing right [diritto], one must take and divide. Whereas for Marx violence is "itself an economic power," for Schmitt the fact that it becomes a legal power is ambiguously affirmed (ambiguously, because the true state of exception — revolution, new world order, civil war, etc. — cannot be a moment disciplined by law, in which the latter, in order to save itself and the state, admits violence by integrating it into its order), while the reality of a new nomos of the earth still involves force, which becomes both a new economic and legal power.

In the primitive accumulation described by Marx, as in his historico-political writings, we find many similarities, mutatis mutandis, with our own situation: a multiplicity of subjects (captors and slave traders, adventurers, pirates, rentiers, financiers, capitalists, peasants, soldiers, merchants, etc.); a multiplicity of modes of production and exploitation (slavery, bonded labor, waged labor, financial exploitation and credit, etc.); a multiplicity of forms of violence (genocide of Indigenous people, expropriation of common lands in Europe and "free" lands in the New World, wars of conquest, subjugation, civil war, inter-imperalist wars, etc.). In this phase of deployed violence, the central role is played by the state ("the nascent bourgeoisie cannot do without its constant intervention," and "all methods of primitive accumulation exploit, without exception, the power of the state") not only militarily as the holder of the monopoly of force ("brutal," says Marx), but also economically, as the manager of credit and public debt, as well as politically/legislatively, capable of churning out special laws ("bloody legislation" against peasants reduced to beggary by expropriation).

Chapter XXIV contains an important Marxian assertion that must be extended to our present day: it is the state that violently precipitates the transition from one order to another (in this case, from feudalism to capitalism), shortening the transition phase through the use of force.

The development of capitalism introduces a radical change in the relationship between state and capital. While it is true that they have always been in a relationship of mutual dependence, from the end of the 19th century, and especially from the beginning of the 20th, the relative autonomy of the state vis-à-vis the economy (Poulantzas) and of the economy vis-à-vis the diminishes, and the two realities start being integrated into a single two-headed machine.

The birth and death of neoliberalism

The definition we have given of the current situation (primitive accumulation and the state of exception) allows us to clear up any ambiguities and confusions to which the concept of neoliberalism may have given rise. From the experience of its birth and rapid decline, we can perhaps draw some lessons for the situation we are currently experiencing.

Thanks to my ripe old age, I have been able to experience and see with my own eyes the alternation between phases of governmentality and moments when the violence of primitive accumulation and the state of exception is unleashed. The two world wars imposed a new nomos of the earth (American hegemony in the West, Soviet hegemony in the East). Unprecedented power relations were then stabilized and normalized in the global North by a governmentality that was sometimes Keynesian, sometimes social-democratic. The new American-led accumulation of capital entered a crisis at the end of the 1960s. The U.S. state-capital machine immediately launched a new primitive accumulation and state of exception that raged over the planet from 1969 to 1979, bringing about the transition from Fordism to post-Fordism. The victory achieved by the state-capital machine in that decade paved the way for a new form of governmentality, neoliberalism, which accompanied accumulation centered on credit and finance, until the latter collapsed in its turn (2008). A succession of financial crises, populism, war, and genocide marked its end. We now find ourselves plunged into the great violence characteristic of moments in which a new order is put in place (if the great powers succeed, which is by no means guaranteed!).

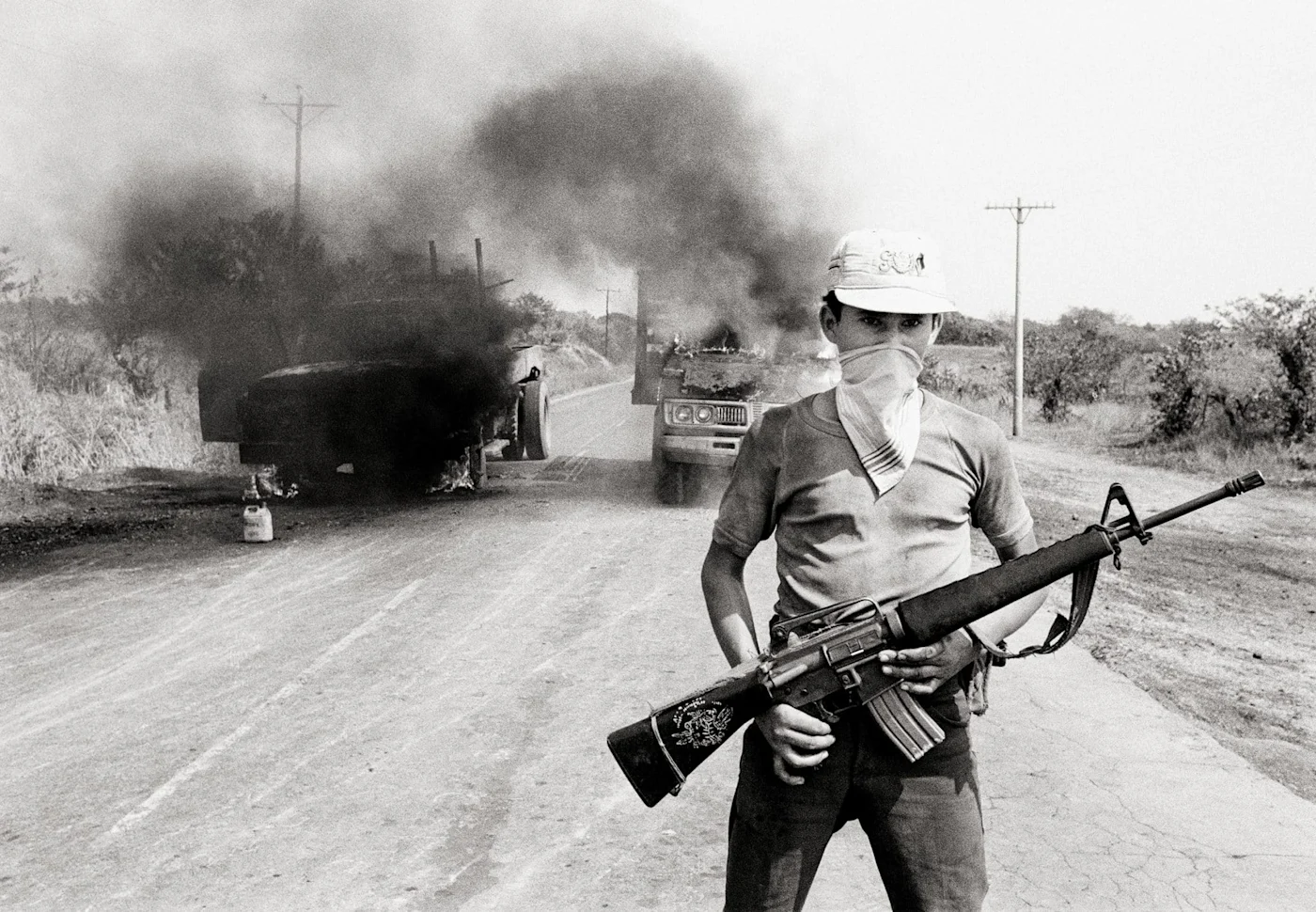

Let us take a closer look at what happened in the decade 1969-1979, which will give us a clearer idea of the form and function of primitive accumulation and the nomos of the earth at the origin of the new globalization initiated during the 1980s, which is now unraveling before our eyes. The global cycle of struggles that culminated in 1968 forced a change of political strategy upon the American state-capital machine, which sought, at first by trial-and-error, then with increasing certainty of its project, to define a new form of accumulation. This begins with the defeat and transformation of class composition, by building a state that is a critique in deed of the Keynesian state, given that the masses had succeeded, thanks to the resolutions of the 20th century, in carving out spaces of counter-power within it. The work of destruction could only begin where the political subject was strongest: the global South. The United States, led by Kissinger, organized an exemplary series of coups d'état in South America using fascist military personnel. The power of the state to declare civil war, impose the state of exception, and use fascists is manifest even within mature capitalism, asserting a right to kill and let live over thousands of communists and socialists. In the North, the relative integration of the working class into the system, made possible by wages and consumption, more simply required political defeat (Reagan and Thatcher). The legal, productive, social norms and techniques that had governed from the postwar period to 1968 were suspended. Without affecting the formal constitution or the law, the material constitution was overturned and profoundly modified. The rapports de force, radically altered in favor of capital, create the conditions for de facto changes in legal norms, productive norms, and techniques of power that do not emerge immanently from Fordist production and the Keynesian state, but must be established by the armed force of fascism and the political force of the state. Violence focuses primarily on the processes of revolutionary subjectivation. New norms cannot oblige in a situation of "chaos" brought about by an unfolding class struggle, as in Latin America. To impose them, one must first establish order at the level of subjectivities; only defeated subjects will be willing to adopt new behaviors, new ways of working, new modes of reproduction.

As in Marxʼs concept of primitive accumulation, in the 1970s it was the state that violently forced the transition from one political-economic order to another, shortening the transitional phase through the use of force. It was not capitalists who, in the 1970s, bombed Allendeʼs presidential residence, imprisoned and tortured thousands of socialist and communist militants (who assassinated members of the Black Panthers, organized the strategy of tension in Italy, etc.), but once victory over the revolution had been won, neoliberal economists sat alongside fascist militarists in South American governments. Only once they have completely normalized the "situation" created by the coups d'état ("sovereign — Schmitt reminds us — is the one who definitively decides whether the state of normality really reigns"), will the neoliberals be able to rule alone, imposing imposing new norms and behaviors. Once command of the state-capital machine has been restored, the situation will be normalized by building a new victors’ consensus, based on the debt economy and consumption on credit, rather than on wages and welfare.

The most important political result of the new primitive accumulation and state of exception will be, as always in capitalism, a new configuration of private property, no longer based on industrial capitalism but on finance: the new principle of wealth distribution no longer places producers at its center, but the owners of stocks, bonds, and financial assets.

It is only after the state-capital machine has sown political death that neoliberalism steps in as the governmentality of new power relations between classes. Only then does biopower (disciplines, biopolitics, pastoral power) take on the mission "managing life" for the defeated subjectivities, and govern their subjugated and subjected existences. The model of power described by Foucault (biopower) is not based on state violence or sovereignty, but on the economy. But is it still true that capitalism and the economy coincide? Contemporary capitalism perfectly embodied by financial predation, the great violence of the appropriation of primitive accumulation and the class war between owners and non-owners, has little in common with an economy where men anthropologically equipped for exchange, to avoid fighting each other armed, prefer to compete in production and trade, according to the aseptic laws of Scottish political economy. Biopower appropriates this pacified image of competition and the market: its aim is not repression, but to encourage, incite, and stimulate the activity of the governed; it works not for war, but for peace. Its model is that of pastoral power, which knows neither violence nor enemies: "The main function of pastoral power is not to harm enemies, but to do good to those over whom it watches. To do good in the material sense of the word, that is: to nourish, to offer sustenance."

This veritable ideology, which opposes biopolitical governmentality to sovereign power by erasing the contenders of class struggle (both the power of the state-capital machine and the power of revolution) has penetrated to the very heart of critical thought, for example, in the so-called Italian Theory, indebted to both the concepts of governmentality and biopower. Agamben, Negri, Esposito adopt these categories in different ways, but seem unaware that their presupposition, in Foucault, is the abandonment of civil war (of class warfare) as a model of social relations. The power relationship is no longer juridical or warlike, but governmental. It is to be sought neither in contract, violence, or struggle. The friend-enemy relationship imposed by the world revolution triggered by the Soviet breakup and reproduced until the 1960s/1970s has become an innocent, peaceful, consensual relationship between rulers and ruled: the assault on heaven is reduced to "no longer being ruled" in this or that way. The new concept of power introduced by Foucault is simply useless compared to its current exercise by the capitalist West.

The war relationship, which had never disappeared but constituted the condition of governmentality, reappears with all its violence when the latter is no longer capable of handling the contradictions of capitalism. It is the suppression of this relationship that lies at the root of the failure of all these theories, which are incapable of anticipating, and foreseeing war, civil war, and genocide — in other words, of understanding the nature of capitalism.

These pacifying narratives were swept away by the very crisis of the economy, the foundation of biopower. What had never retreated has reappeared, with all its terrible force: sovereign power over life and death, a sign that a new primitive accumulation is preparing to create the political conditions for a new world order. Classical liberalism was wiped out by the First World War, but capitalism continued to reproduce itself, allying itself with fascism and Nazism. Neoliberalism is dead, but capitalism persists through war, civil war, and renewed alliances with new fascisms, taking assuming the great violence of genocide.

A new concept of production?

From what we have said, we can deduce that primitive accumulation and its great violence, just like the state of exception or nomos of the earth, and above all class struggle, must be an integral part of the concept of production, and constitute the presuppositions that, in each case, determine its form. In this way, we are definitively freed from the ambiguities and limitations, even Marxian, of the concept of production, which often risk leading its epigones into embarrassing economism. Violence, war, civil war, and genocide are not an accident of capital accumulation, but its structural and founding elements.

In the 1960s and 1970s, several attempts were made to enrich and broaden the concept of production, in an attempt to overcome the economistic limitations of Marxism at the time: libidinal economy (Lyotard), the economics of affect (Klossowski), the discourse of the capitalist (Lacan), desiring production (Deleuze and Guattari), biopolitics (Foucault), and Negri's Spinozist ontology of being as production. All these theories seem to take a step forward from a theoretical point of view (since capitalism also functions through desires and affects), but from a political point of view, they take two or more steps backward, since they have contributed to pacifying capitalism by separating production from wars and the radicality of class struggles.

Capitalism is born of great violence, massacres, genocides, dispossessions, wars and enslavement. The state-capital machine renews, reproduces, and imposes itself through a barbarity that grows steadily over the centuries, in proportion to the development of the productive forces of labor and technology which, if not directed towards emancipation by revolutions, converge towards the destruction not only of variable or fixed capital, as crisis Marxism maintains, but also of the human species and its world.

The bloodthirsty fury that grips our rulers is neither a psychological trait, nor a mental illness, nor anything new. It is repeated with disconcerting regularity, and to have excluded it from the definition of capitalism and capital is simply idiotic and suicidal. To have reduced capitalism to the market and power to discipline, government, and biopolitics, in the belief that these had finally decapitated the modern Leviathan (which brandishes the symbol of political power in one hand and economic rather than religious power in the other) when in fact it continues, undaunted, to decide life and death, is one of the most disastrous outcomes of post-’68 critical theory. The truth of its deadly exercise is today easily verifiable, but the confrontation with the reality of class warfare seems impossible to assume in a West, which is now in its definitive twilight. Capitalist profit and state power feed off each other, but in times when primitive accumulation continues to act in synergy with the state of exception, the sovereign power to kill, to take, and to divide necessarily predominates. This power can no longer be identified solely with the state, but rather with the political force of the state-capital machine that decides and guides strategy. The flip side of this situation is what, from the point of view of the oppressed, can be called the Leninist moment, that is, the moment when the impossible of revolution can become possible (provided, as always, that the subjective conditions are right).

What is democracy?

Democracy existed only for a very short time in the West, thanks to the class struggle and revolutions of the 20th century. With the latter gone, it has reverted back to what it always was for liberals: democracy for owners (Marx recalled that the material constitution in the West is property), democracy for war and genocide, democracy for fascisms.

There is one element missing in the Marxian primitive accumulation: fascism, which in fact emerges with imperialism. Monopoly capitalism, unlike competitive capitalism, "no longer develops a tendency toward socialism, but if anything, toward fascist barbarism," suggested Hans-Jürgen Krahl.

One of the most distinctive features of historical fascism is that, unlike communists and revolutionaries, it has no need to seize power, because it is offered to it on a silver platter by the ruling classes, frightened by their own crises, which each time make the abolition of private property (the only true foundation of the West) a reality. Fascism and Nazism are indispensable to the existence and reproduction of the state-capital machine, when it mobilizes primitive accumulation and the state of exception.

The same thing is happening, mutatis mutandis, today. The French “banana republic” is an exemplary case in point. At the time of his reelection, President Macron no longer had a majority and governed by decree, completely depriving parliament of its power (a process underway since the First World War, and only deepening!). Having lost the European elections, his plan was to bring the fascists to power, as his predecessors had done in the 20th century, because they represent the ideal solution in times of capitalist disaster: they apply the policies of capital like the liberals, but with "illiberal" governance.

Consider the so-called anti-system positions of the Italian fascists who are already in government. Once in power, they immediately abandoned sovereignism, becoming obedient executors of Europe's orders and servants of Atlanticism, while pledging to sell the "homeland" to American pension funds. Fascists, those great patriots, throw their borders open to "foreign" capital to impoverish the "motherland," while closing them to a few thousand migrants or deporting them to Albania. For dutiful service to the American masters, their servant Meloni has been rewarded by the Atlantic Council (whose name says it all).

The government has also cut resources for health care and public schools in order to promote the privatization of all public services, which is precisely the policy of American funds. It has impoverished the country, especially pensioners, passed liberticidal laws against strikes and demonstrations, and even invented the crime of passive resistance (called Gandhi). It has not taxed the enormous profits of banks, insurance companies, multinational energy and pharmaceutical companies, or digital giants (GAFAM). It has encouraged legalized tax evasion, also called tax optimization, another precondition for financial capitalism. This massive transfer of wealth to the pockets of the bosses has emptied the public accounts, and now the fascists are calling for “sacrifices.” For the next seven years, after speaking out against austerity when she was in opposition, Meloni is imposing cuts of twelve billion euros a year in public spending to comply with parameters set by the new European Stability Pact (also harshly criticized before coming to power). Fascists are more liberal than liberals in economic and fiscal policy. The only ground on which they keep their fascist promises is the repression of all dissent and difference. Are French colleagues still unable to gain power through elections? Macron takes care of that, convinced that dissolving parliament and calling new general elections was the best way to pave the way for these more-than-reliable allies (but who can always go their own way, like the Nazis). No such luck! The fascists lost, as did Macron, and the leading political force turned out to be the left. The president immediately refused to recognize the results of the elections. In a situation of primitive accumulation and nomos of the earth, where only force counts, one must do what the state-capital machine requires. Democratic norms are de facto suspended and depend upon the will of the democratic “sovereign” Macron, who appoints a government where the entire right is represented, from the republicans to the fascists, i.e., the forces that came out defeated in the elections. The government exists only thanks to the abstention of the fascists who hold it under their thumb and, by publicly displaying it, boast about it. The political path was open to fascist power; all that was missing was the economic one. Here it is: the new government must cover the budgetary gaps left by the previous bankers' government, which dispensed billions in public funds to corporations and the rich with immense generosity. Now state spending must be cut by sixty billion euros, which can be achieved only at the price of austerity on the same value (two percent of GDP) as that imposed on Greece by magnanimous Europe.

Nazism did not flourish between the wars because of inflation, as the German democratic storytelling maintains, but because of the austerity imposed by the 1929 crisis. All the conditions are ripe together for the fascists, rejected by “the people" in the elections, to come to power in the near future. Voilà la démocratie!

The situation of all Western democracies today is perfectly rendered by Carl Schmitt's concepts of "just war" and "open or latent civil war": "both,” he writes, “absolutely and unconditionally, place the adversary outside the law." NATO's mishandling of the war in Ukraine strips all rights from the adversary (Russia, behind which China is already looming) in the name of the political and moral superiority of co-called democracies (including Israel!). Enemies are criminalized to the point of being transformed into the "uncivilized," "barbarians," "savages," definitions that activate colonial memories. Hostility becomes absolute "in the paroxysmal belief in one’s own right." The same rhetorical and political procedure is applied to the enemy within, in a civil war that is still latent but already manifest in "legal and public defamation and discrimination, public or secret proscription lists, declaring someone an enemy of the state, the people, and humanity," aim at suppressing even the smallest dissent towards the war with Russia or the genocide of Palestinians. Where media rhetoric and politics are not enough, the police step in. The shameful use of anti-Semitism perfectly sums up today’s definition of the enemy. Since the beginning of the war against Russia, and even more so with the genocide unleashed against the Palestinians — two moments in the confrontation with the Global South — Schmitt’s defining principles of just war and civil have been openly implemented against all those who do not bow to the ongoing militarization: "Doubt about one's own right is regarded as treason; interest in the opponent's argument, as disloyalty; attempt at discussion becomes agreement with the enemy."

Schmitt's analysis offers us a perfect dissection of the situation surrounding the wars (just war, open or latent civil war) that capitalist democracies have chosen as their ultimate and desperate attempt to halt their inevitable decline.

To conclude: while it is not true that capitalism must inevitably lead to socialism and communism, it is absolutely true that, with disconcerting regularity, it does lead to war and civil war.

First published in Italian October 29, 2024

Translated by Ill Will

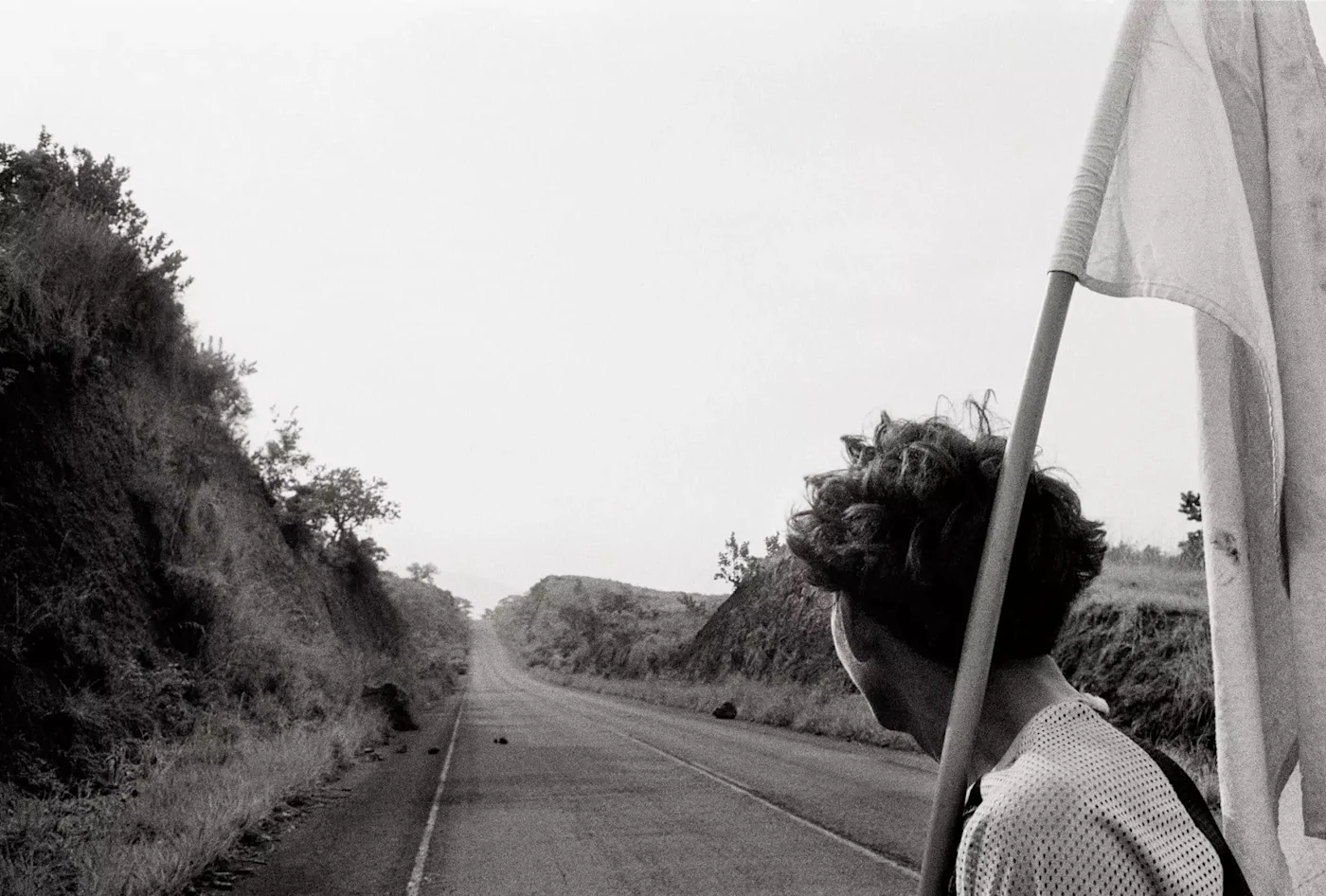

Images: Robert Nickelsberg