Palestine’s Lessons for the Left:

Theses for a Poetics of the Earth

Rodrigo Karmy Bolton

Other languages: Italiano

There is no Homeric echo here...only a general looking through the rubble for the awakening state concealed within the galloping horse from Troy. —Mahmoud Darwish

1. Justice becomes struggle.1

The confrontation with Zionism, which subjectifies the Jew in the form of the absolute victim, is by no means gratuitous: it implies that the Jew be stripped of their victim status, that they become a “bad victim” precisely by rejecting this form of subjectivation, this position in the world. In this way, another right is forged in the struggle, a right that, as Tariq Ali observes, would entail the collapse of the doctrine of human rights crystallized in the institutionality of the United Nations. In the struggle of this other right, that entire world collapses, that whole institutionality sinks and from its ruins another conception of justice is born. What is being forged in peoples’ struggles today — including the Palestinian people above all — heralds the future of a right, and the right to a future. If the doctrine of Human Rights is based on the idea that a human being or a group of human beings becomes a “victim” because they were brutally harmed by state terrorism, this is precisely in order to make them demand “reparation.” Justice is conceived in this way as the drama of a “victim” that is “repaired” by the state. Such a scheme maintains intact the sovereign apparatus — and the notion of the sacredness of life — through which a crime that must now be “repaired” was forged. As long as there is a “victim,” there will be a killing machine; as long as there is a “victim,” there will be no other justice than “reparation”; as long as there is a “victim” human life will always be regarded as sacred, that is, within the sovereign relation that prepares it to receive death. The struggle of the people today, on the other hand, carries with it another conception of justice that does not rest upon the idea of a life that has been “victimized,” that is not consoled by the possibility of an eventual “reparation,” but instead by the actuality of its own unfolding struggle. If justice as “reparation” breaks down, because its ultimate representative — the United Nations — and its moral beacon — Israel — collapse in moral terms (the former because of the genocide it gazes upon, the latter because of the genocide it commits), it is precisely because the global insurrection of the peoples of the world has opened up another form of justice, one that does not pass through the notion of “reparation” but through that of “struggle” itself, one that does not accept the position of being a “victim” but instead wagers on a martyrological ethic rooted in the intensity of struggles.

2. Progressivism has no vocabulary for understanding justice as struggle.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the left embraced a version of liberalism; ever since, it has become just another liberalism. Consequently, its discourse can refer to anti-colonial resistance only with the reactionary term “terrorism.” The left’s lexical vacuum thereby facilitated the triumph of reaction. Having discarded any critique of violence, the lefts-cum-progressivisms have remained inane in the face of struggles that pose diverse forms of violence, among which the most important continue to be the anti-colonial struggles like that of the Palestinian people. Of course, those who storm heaven through their struggles do not wait for progressives to recognize them. Rather, just the opposite has occurred: anti-colonial uprisings (some of them armed) have left progressives mute, unable to think their own epoch nor speak in its dialect (this might even be what makes progressivism what it is). We are in need of a critique of violence that can provide an idiom or dialect that does not allow the notion of “terrorism” to occupy the throne, which rightly belongs to the political “struggle” by which the justice of the oppressed is forged.

3. Islam can be a revolutionary force.

Centuries of enlightenment thought have made the left suspicious of every sort of “religion.” In a famous passage in his “Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right,” the young Marx writes: “Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.” The cliché-like repetition of the phrase “religion is the opium of the people” in enlightenment discourse resulted in making “religion” into a fictitious enemy, which overlooks the rest of the passage in which this enigmatic phrase is situated. “Religion” is the “opium” of the people, Marx claims, because it operates in a two-fold way: it is “the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering.” Religion carries within it, therefore, a refuge of the future even as its own form of expression denies it. Its place is that of a contradiction which at once diagnoses the present state of things and projects an image of their overcoming. In this sense, the Western left has been profoundly anti-religious and therefore incapable of articulating class alliances that would allow it to overcome the current state of affairs. Seen in this light, the preponderance of Islam in the Palestinian resistance movements is not accidental, but corresponds to the cartography of forces distributed by the recent lacerations of history. An imperialist history, to be sure: in the 1960’s there were nationalisms and “secular” discourses that promoted national liberation. But, once those processes of decolonization were completed, many of them were co-opted by the same imperialism they claimed to be fighting against (as in the case in Egypt). In this way, the former pan-Arab liberators became the guardians of the newest colonial phase. It is in this context that Islam takes up the spirit of anti-colonial struggle that the secularists abandoned. Palestinians voted for Hamas in the 2006 legislative elections not because they want an Islamic State, but because they see in such a wager a possible path to the end of Zionist colonization. The resistance movements in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank today are divided into three groups acting together: Islamist, Marxist, and nationalist (Fatah) movements. Their solidarity is rooted in a shared passion, the anticolonial passion, the passion for the liberation of Palestine. Contrary to the dogmatic conception of the Western left, which automatically sees in “religion” and, above all, in “Islam” a bastion of oppression, the Arab lefts — Palestinian in particular — have understood that the constellation of powers can only be articulated in common. The Orientalism that Edward Said denounced persists in the Western left, which can’t understand that Islam can assume a revolutionary position, and remains suspicious of all national liberation simply so long as its movement is articulated through so-called “religion.”

4. They claim to be targeting Hamas and Hezbollah, but they are targeting us.

Since October 8 2023, the primary target of Israeli action has been the civilian population. Their logic is not the one most people assume, in which they first go after the “terrorists” and only by “accident” hit the civilians. The situation is just the opposite: the goal is to decimate the civilian population in order to make the groups they consider “terrorist” disappear along with it. In other words, they’re not going after Hamas or Hezbollah. They’re going after us. The terrorist incursion into Lebanon makes this clear: it doesn’t matter who uses the mobile devices: they are blown up without any discretion. If civilian and military, external and the internal aspects of the war blur together beyond distinction, this is because the ultimate aim is to annihilate the population in order to render resistance meaningless. Nothing more, nothing less. The situation is the opposite, therefore, of how it has been conceived up to now: it is not that the imperialist forces shoot at the resistance in order to capture the civilian population, but instead that they take aim at the civilian population in order to crush the resistance. This inversion of terms implies, incidentally, that a quite precise message is sent: no one is safe anymore. In the logic of the war against terrorism, no one, absolutely no one, is safe. Everything becomes Gaza to the extent that anyone can become a terrorist. This is why our era is none other than the era of global civil war. It was never about Hamas or Hezbollah, it was always about us. It is we, as a population, who are the primary target of warlike aggression; it is we who, for whatever reason and under whatever circumstances, can be deemed undesirable and annihilated, as is the case today with Palestine and Lebanon. For this reason, the cliché of the “human shields” that Hamas is supposed to use is nothing more than the crude justification of the extermination of the civilian population, now that the latter has become the primary site of war. Some celebrate the technical deployment. The futurists (an aesthetics of the future celebrating technologies of annihilation offering admiration for assassins with computers), the children of Marinetti, multiply because capitalist machines multiply. Futurism dreams of the extermination of the undesirables, where everything functions “perfectly” — this project must be defeated again today, just as it was yesterday.

5. Kamala Harris is the Joker.

When we look closely, one finds in Kamala Harris something that is every bit as obscene (if not more) than what we find in Donald Trump. The candidate that laughs versus the candidate that hurls insults, the youthful candidate versus the aging candidate, the woman candidate and perhaps the first woman president of the United States versus one of the most chauvinist (let’s not say the “most chauvinist” [más machista]) of the liberal American oligarchy. But this binarism ends when we look at it from the vantage point of Palestine. There, it is all the same. The candidate that laughs while she loves Israel and promises to keep the war machine going can’t be less deranged than Trump. As Vice President, Kamala kills while she laughs, murders while she smiles. She is the Joker, Batman’s old enemy (Trump is the degenerate Batman) — her laughter is far from comedy and much closer to sadism. Kamala’s laughter expresses the Democrat’s pleasure in war, the joy of laughing while killing. Pro-Palestinian delegates to the Democratic National Convention were denied participation by their own party as Kamala was selected for candidacy: Palestine banned, Palestine once again excluded, expelled from the territories. Kamala is founded, therefore, on the exclusion of Palestine. And, what’s more, on the renewed love for Israel. Just like Trump. Seen from this perspective, the difference between Harris and Trump does not reproduce the classic opposition of Democrat to Republican; rather, given that Dick Cheney, with blood on his hands from Iraq, and John Bolton, murderer and coup-plotter in Venezuela and former member of Trump’s cabinet, both plan to vote for Kamala, what is at stake is whether the classic American oligarchy will prevail over Trumpist caudillismo [i.e., authoritarian populism] and its thirst for civil war. What is at stake in the American election is the reinstatement (or not) of the classic oligarchy’s governability, with its capacity to provide forms of containment to the fragile situation of the country. If the tension in the US emerges from the question of the capacity to articulate the territorializing pole of the nation-state versus the deterritorializing pole of the expansion of its imperial security policy, it is because the oligarchy has been the class force capable of articulating these twin movements of the machine. If the oligarchy implodes, it is because the machine itself has proven unable to articulate the intensity of these two poles. Kamala is the Joker: she cackles and bombs, cheerfully waging war, a huge grin on her face as Cheney and Bolton parade at her side.

6. Palestine offers strategies.

In fights over “doctrine,” the left should really understand that the “doctrines” in question are strategies, contingent modes of undertaking the transformation of the world. Doctrines are simply strategies that have become frozen, and, consequently, have paralyzed struggles by trapping them in endless debates over these “doctrines,” over who is more faithful to the theology of this or that author. Palestine laughs at all of this, because the baseline assumption there is that there exist many forms of struggle, weaving a strategic plexus that one day might support a resolution of the UN Security Council and next join together in a popular uprising. It is possible to take up arms, and then later support an institutional politics. This is not a question of doctrine but rather of strategy, not of faith but of politics. The left today has no strategic future beyond the painful administration of capitalism. Palestine teaches us that it is possible to go further and struggle against the future of capital, above all against its newest phase of accumulation via the intensification of its colonial forms, be it through the arms industry, the expropriation of water, or the spread of settlements.

7. The Nakba is unfolding before our eyes.

While the Palestinian Nakba [catastrophe] constitutes the event that marks the colonial history of Palestine, it is not restricted to the Palestinian territory in particular but functions as the paradigm of our present. In this sense, in Palestine the Nakba finds its intensification, while the planet itself is its massive space of consummation. We find ourselves in the becoming-Nakba of the world, where “Nakba” corresponds point by point with the violent history of capitalism whose neocolonial forms devastate the planet. Israel is the name of capital (“the promised land” is its slogan, which is to say, the territory available for colonial exploitation). If Israel has been intensifying its deployment of the Nakba in Palestine since October 8 2023 — and neo-fascism has been intensifying on a planetary level for several years now — today the becoming-Nakba of the world signals a global civil war that is differentially distributed in varying degrees of intensity in different parts of the world, with Gaza as its degree zero. In Gaza the intensity is beyond measure because Gaza is not simply a territory but a concentration camp.

8. The spectacle is extermination, normalized.

It has been endlessly repeated that we are watching a genocide unfolding in real time before our eyes. Nothing is hidden, nothing is secret. We should question ourselves in the face of this unusual nudity. The nudity of criminals. What is at stake here is a criminal education. The idea is to send a message: enjoy the violence, enjoy the massacre, and you will see how extermination becomes normalized. The greater the media saturation, the less the surprise, the less the horror. And as Nietzsche says, philosophy begins with horror.2 Once it is neutralized, inscribed in the routine of standard procedure, there is no more horror, nor is philosophy possible. In fact, nothing is possible at all, because there is nothing more to say. The nihilization [nihilización] of horror makes possible the normalization of extermination through the media’s daily education. Thanks to Guy Debord, we know that the media is not a simple tool of communication but rather an apparatus designed to capture affect: the spectacle is a “social relation,” as Debord said. The Zionist education of mass media aims precisely at a capture of this sort, through which the normalization (and its de-affection) of extermination can be exposed to the light of day. A capture of affect, and not merely a distortion of knowledge about reality. Unlike the Nazi extermination that remained hidden, the Zionist one saturates the screen and its media. Whether extermination is hidden from the media (Nazism) or saturates the media (Zionism), we are being disciplined by the spectacle, dis-affected, ethically destroyed. No one can claim that they didn’t know, but “knowing” here offers the spectacle of one’s own impotence. It is precisely because we “know” that we do not act; our “knowing” is our re-education, normalizing a genocide that does not cease to extend itself ad infinitum.

9. Zionism is not Judaism, but a “Christian” and imperial translation.

It is necessary to understand that Zionism is older than the State of Israel. Older, even, than Jewish Zionism, which arose towards the end of the 19th century in the form of a colonial movement. In this sense, Jewish Zionism is a right-wing culture (despite its transversal overtures towards certain leftists and progressives). Zionism was a properly Christian invention of an imperial sort which, before being a State, sought to constitute Israel as the “driving force” of Western imperialism. Why? Because in the eyes of Protestantism “Judaism” was seen as the most original and authentic mode of revelation. To accede to this revelation means undertaking the historical mission to return the Jews to their “territory” and thus, in the form of a salvific mission, to establish a foothold for the deployment of British imperialism against Spanish Catholicism supported by the Church and French secularism as conceived since Napoleon. To accede to the authentic and uncontaminated word means, in this case, to invest oneself with the sovereign power of God, to drink from the most original source of his Word and to legitimize, in this way, under a supposed divine investiture, the imperial exercise. Thus, both the British Empire and American imperialism are structured by Zionism insofar as, according to this dispensationalist theology, Zionism arises as the force of restoration of the kingdom of Christ once the Jews return to their “territory.” This is also why Giorgio Agamben was able to assert that Zionism marks “the end of Judaism,” since, in its territorialist zeal, Zionism crushes the historically exilic dimension that has always defined Judaism.

10. We need a poetics of the Earth.

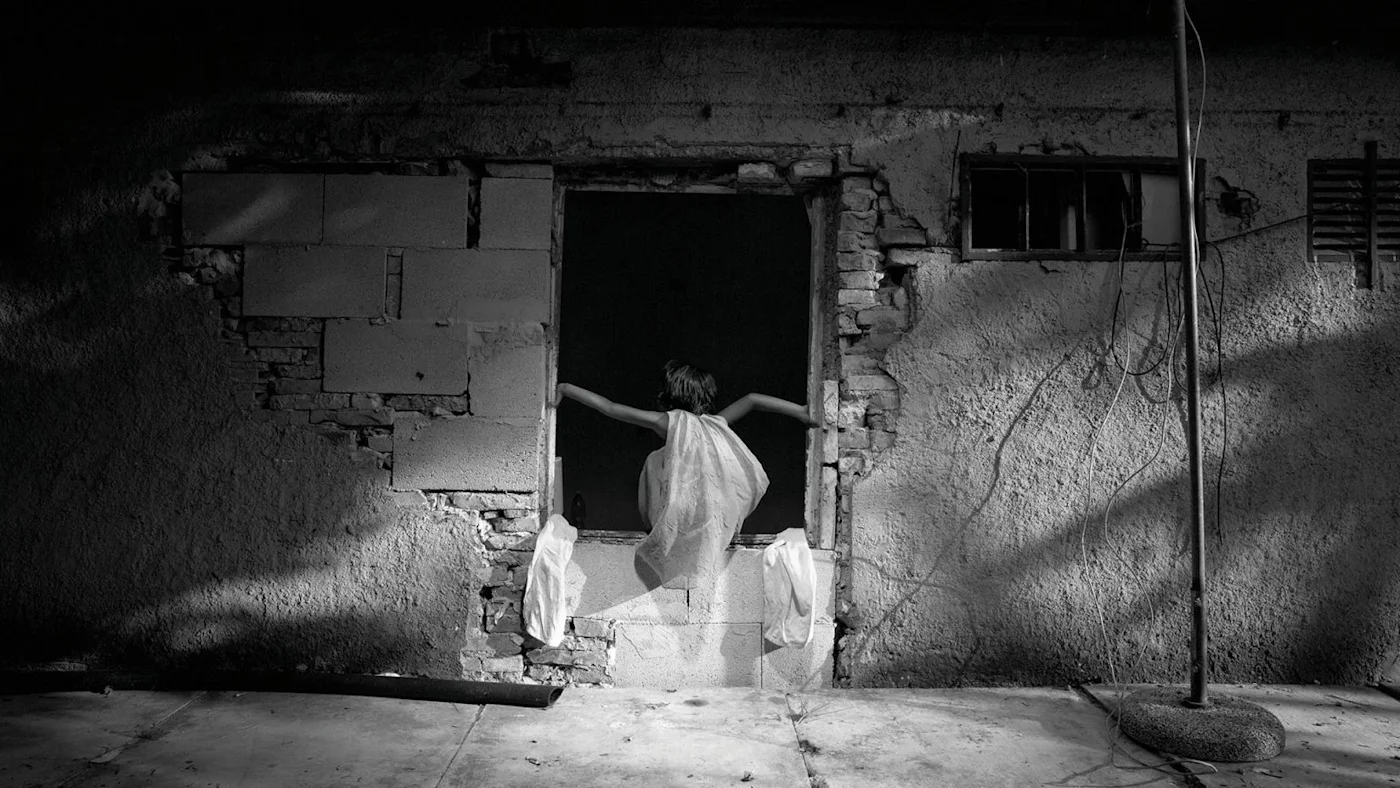

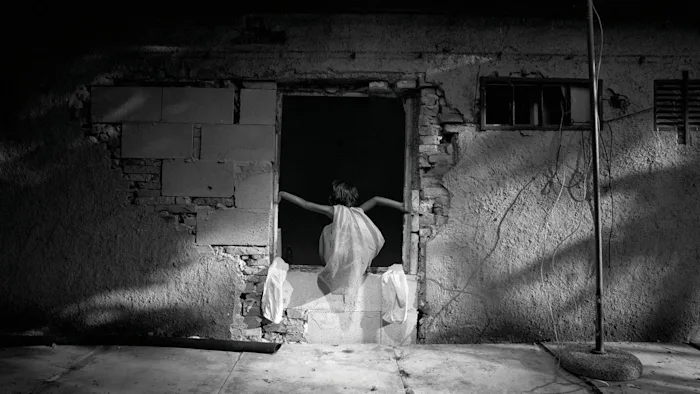

Palestine teaches us that until now human beings have not inhabited the Earth. We have conquered it, appropriated it towards its exploitation, which has likewise been our own. But we have not inhabited it because we have not placed it in common, we have not removed it from the regime of capital. In other words, we have not achieved an experience of the Earth but only of the territory on which capital is founded. We have not cultivated gardens, but only exploited plantations. We have seen everything through the prism of appropriation and forgotten the possibility of use. For a little more than six thousand years, an ancient Neolithic legacy has been dragging us along, driving us to conquest. Even when we speak about interplanetary travel we speak in terms of conquest and the problems of territory — not of the Earth — burst forth with their borders, flags, and expropriations. We dream of the flight to outer space, but we have never left our territorial paranoia. Habitability is defined as a poetics of the Earth, which is to say, an experience of the commons in which it is not property but use, not conquest but inhabitance, that defines our existence. On this plane, what the intifadas [revolts] of recent decades give us a glimpse of is precisely the asphyxiation of all inhabitance brought about by capitalist devastation, along with a desperation to return to a common experience in which the plazas, streets, and walls become places where the Earth bursts forth rather than a territory, an erotics rather than an order. The intifada is a poetics that cannot be territorialized, one in which banners, songs, and images give a face to the city; exactly the opposite of that capitalist urbanization that transforms places into museums that no one can use because it appropriates them all. In this light, the colonization of Palestine is, more than anything, the devastation of any possibility of a face. When the Palestinian people paint their side of the wall erected by Israel, they are, strictly speaking, inhabiting it, transforming it into a great recipient of popular imagination in which Camilo Catrillanca’s face dances alongside Ahed Tamimi’s.3 The possibility of transforming a wall of oppression that has divided territories into a place where hopes are inscribed nicely captures the meaning of a poetics of the Earth: a poetics that does not reside in an unattainable “beyond” (it is not an “ideal”), but in the concrete experience of global insurrection.

(September 2024)

Appendix: The End of the Wall is the End of All Walls4

A few days ago, the Israeli historian Ilan Pappé asserted that the Zionist project of colonizing historic Palestine is collapsing. In spite of the extermination underway, but also precisely in relation to it, we must uplift an image that, in my opinion, precipitated the moment through which our present era is passing. The incursion of Palestinian militias on October 7, 2023 into the territories occupied by Israel since 1967 had a comical episode: not the armed militias, but a Palestinian who mounted a bulldozer and drove it to break through the fence that divides the occupied territories from the Gaza Strip.

The bulldozer has always been the favored machine of the Israeli occupation. With it, they have destroyed Palestinian houses and prepared the land for new Israeli settler colonies. However, that day the bulldozer was used by Palestinian forces. Not to demolish Israeli houses but to break through the siege with which Israel has suffocated Palestinian life. The collapse of that small fence made of flimsy metal condemns the Zionist project to collapse and signifies the hopes of the Palestinian people. “Collapse” in the sense that such a project today can claim nothing for itself but a racist and genocidal policy without nuance; “collapse,” insofar as its machine has become discursively exhausted, exposing itself, its own limits, its end. When the Palestinian bulldozer broke the siege, it made visible the end of the Zionist project. An end that involves that breakdown of the wall, revealing that the built wall was already a symptom of said end because it constituted the performative mechanism erected to compensate for the exhaustion of its project and the complete implosion of its authority.

In this context, one must consider the permanent triumph of the far right in the Israeli government in recent decades: its commitment to intensifying the policy of illegal settlements and thereby fulfilling their goal of colonizing all of historic Palestine, completing the Nakba begun in 1948, is not an exception to the Zionist project, as progressive Zionism illusorily insists, but rather its total consummation. And because the far right is its consummation, it is, at the same time, its exhaustion. Given this, the end of the wall brought about by the Palestinian bulldozer is the image that, in reality, precipitates the end of all walls.

The Palestinian resistance opened an ethic in the sense that they put into play a common experience in which something like a world becomes possible again and whose name goes by the term “solidarity.” Because “solidarity” is the name of the eroticism with which the people of the world embrace each other in times of danger and, in this sense, the destituent moment in which all the walls — designed to seal off, compartmentalize, divide, and suffocate the multitude — experience their end.

Everything that approaches or names Palestine becomes clandestine in as much as it must circumvent implicit or explicit forms of censorship... Nevertheless, there is not a day that Palestine doesn’t erupt on to the world stage. Its clandestinity begins to bring an end to all walls and to embrace common experience. Because there are other walls like the one Israel has built over Palestine; like the one dividing the United States from Mexico and the rest of Latin America, like the class walls built to keep large masses of the population on the margins, or like the communications walls (of large media corporations) within which certain issues cannot be raised except at the cost of breaking the terms of what those in power usually call “coexistence,” “peace,” or even “democracy.”

The proliferation of walls suffocates; yet precisely for this reason, Palestine has become the name of a solidarity that unlocks the power needed for the end of all walls and that says “we can” tear down the walls. Not only “we must” as a moral imperative, nor simply “we want” as a will, but “we can” through the materiality of bodies that intensify their collective power and potential.

In fact, each time we utter it, it becomes more and more plausible to pronounce the name Palestine and denounce the crime to which it has been subjected by Zionism: a protest floods the streets of some city, students camp outside a university or, upon graduating, display a Palestinian flag, an anonymous person paints a mural about Palestine or a deserted and dry wall proclaims “Free Palestine!”, athletes who mount podiums wave a flag or keffiyeh, tricolor stickers (red, black, white) are plastered on endless corners and light posts, determined university authorities decide to end academic collaboration with a racist and genocidal state such as Israel, and even some presidents decide to cut diplomatic relations with the Zionist entity.

In this sense, we are witnessing the war of the walls, an unprecedented process by which they are weakened and begin to crumble, because they can no longer fulfill their function.

In this light, the decision of the Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy and Humanities at the University of Chile to terminate an agreement with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem constitutes a milestone that could mark the beginning of another historical era in which the reign of force gives way to justice.

May 2024

Translated from Spanish by Ill Will

Notes

1. Some of these theses were shared on a panel about internationalisms as a part of the seminar “Mi felicidad es la lucha” [My Happiness is the Struggle], and dedicated to the memory of Miguel Enriquez, on the 50th anniversary of his assassination by the dictatorship. The seminar took place in the National Archive of Santiago. ↰

2. I am grateful to Carlos Ossandón for reminding me of this line by Nietzsche.↰

3. [Camilo Catrillanca was a Mapuche indigenous warrior in a southern territory colonized by Chile, murdered by Chilean anti-terrorist police. Ahed Tamimi is a young Palestinian militant. She and her family have been repeatedly harassed and imprisoned. —Editor’s note.]↰

4. “The End of the Wall is the End of All Walls” was first written on May 21, 2024. It was translated here into English for the first time by Liz Elias. ↰