Phantom Pheminists

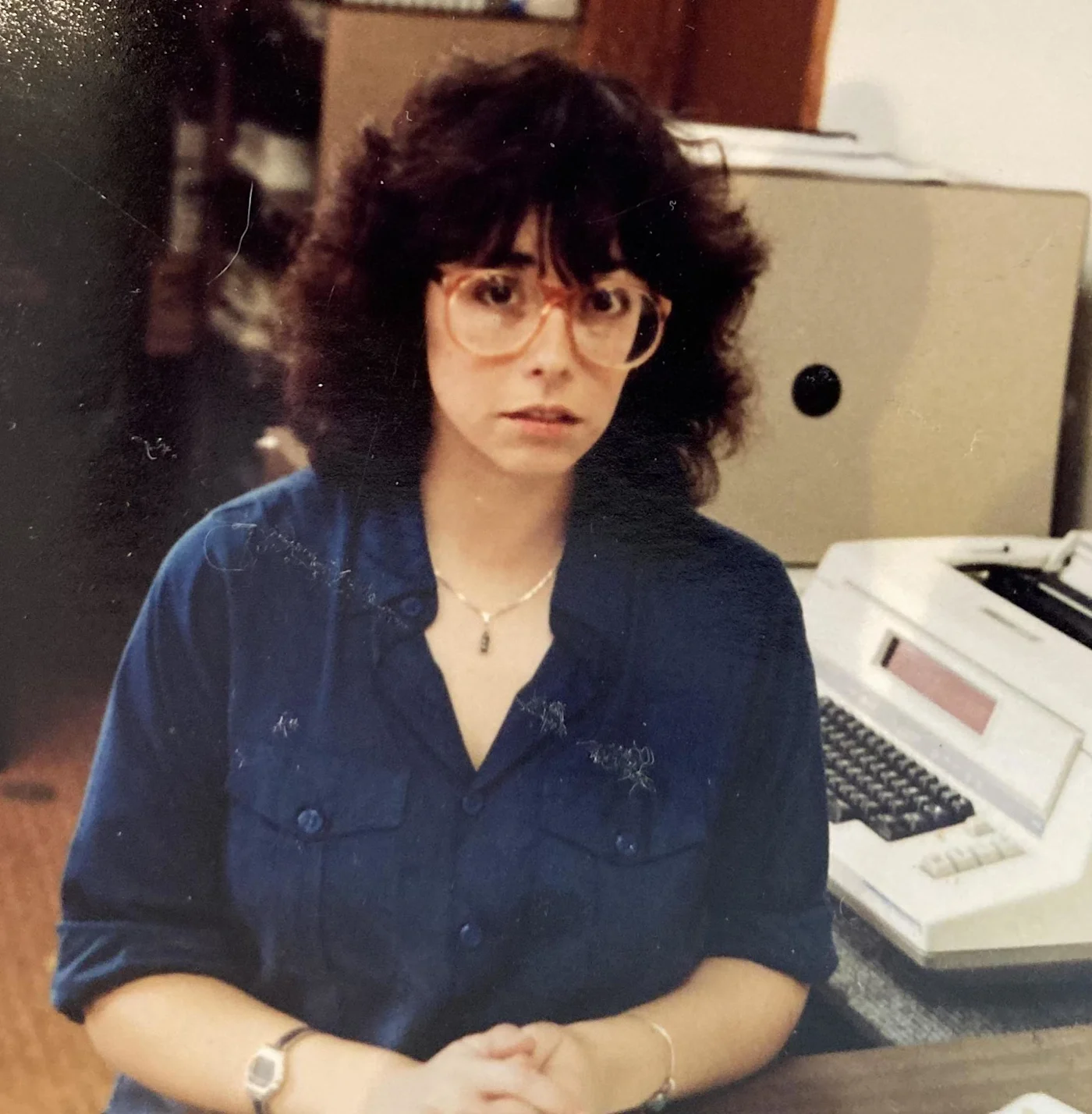

Elizabeth Henson

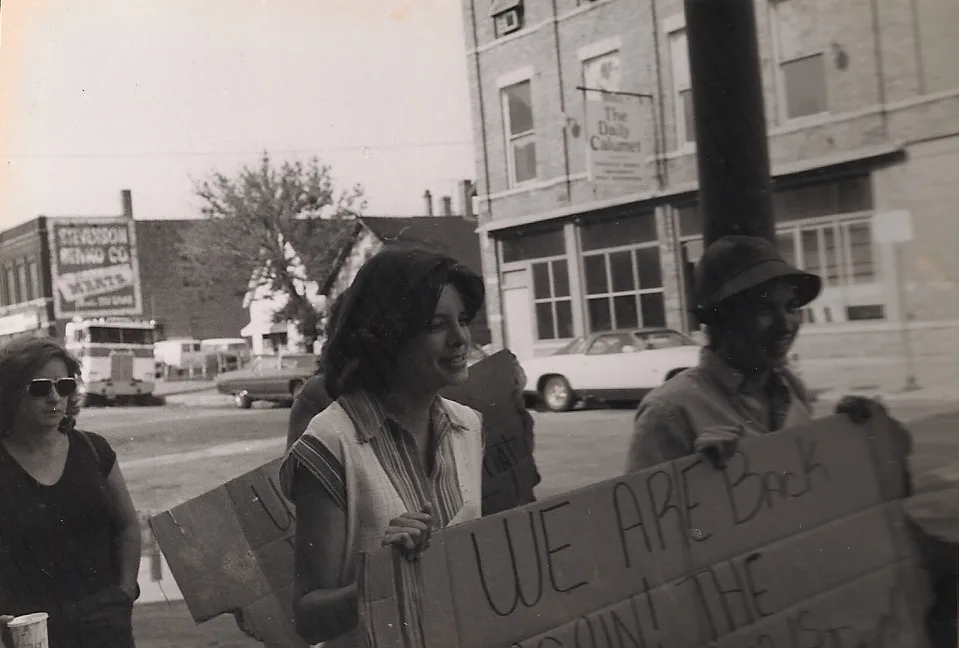

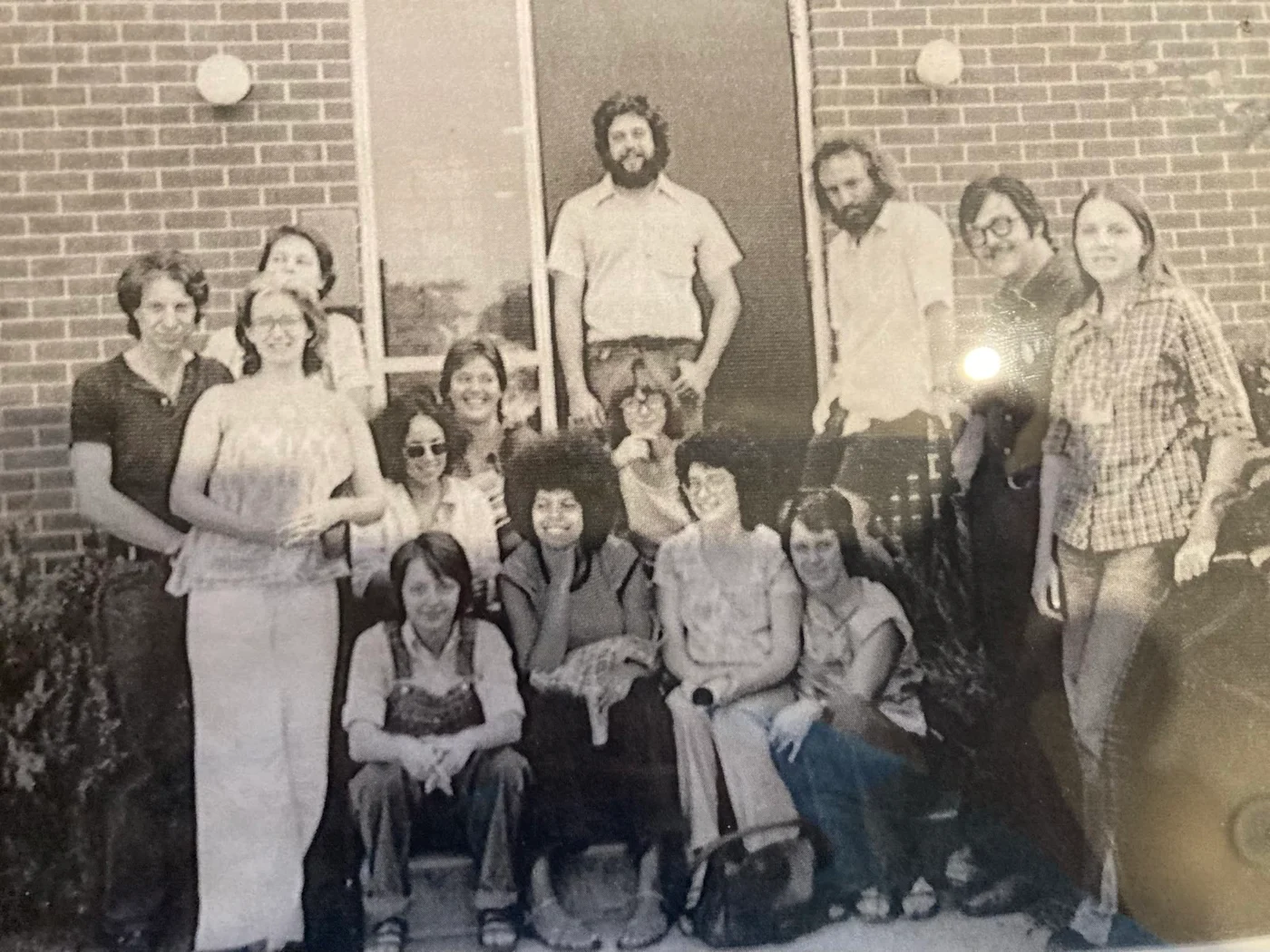

What follows is an account of an internal struggle over male chauvinism in the Sojourner Truth Organization (STO), a small autonomist communist organization. I was a member from the mid-1970s until 1981. The battle began with a list of sexist sexual come-ons and ended with a male leader convicted — by a narrow margin — of having an affair. The entire struggle took less than a year, 1980, and was our only attempt to deal with internal gender issues on more than a local level. Our failure was rooted in disagreement among the women, between the ones who brought it up and were accused of “white women’s oppression,” and the ones who rejected the initial campaign.

In 2012, following the publication of Michael Staudenmaier’s book, Truth and Revolution: A History of the Sojourner Truth Organization, 1969–1986, the journal Insurgent Notes published a symposium and invited former members to comment.1 Ken Lawrence used the opportunity to crow that STO had “repudiated” the notion that the personal is political, and mentioned the Phantom Pheminists only to celebrate their defeat.

STO was never able to confront the question of gender because so many of us were in relationships with each other and we could not discuss it. The personal and the political were so deeply entwined that we were helpless. When was Ken or Noel being arrogant, and when did their arrogance indicate a structural dynamic we could call male chauvinism? To answer this question would have required that we analyze power relations among us, which meant admitting to an imbalance.

This recounting is based on contemporary documents and is part of an unfinished memoir, We Wanted to Change Everything.

The Sojourner Truth Organization never developed a position on gender because the women did not agree, so our attempts never got off the ground. We did agree that our participation in the autonomous women’s movement should follow our general political line; consequently, many of us were active in the reproductive rights movement, where we emphasized sterilization abuse (usually directed at communities of color) rather than abortion.

In 1976, STO published Alison Edwards’s pamphlet, Rape, Racism, and the White Women’s Movement.2 Rape, Racism was a criticism of Susan Brownmiller’s Against Our Will, where Brownmiller framed rape as a crime of power, the “conscious process of intimidation by which all men keep all women in a state of fear.” Alison pointed out that the book promoted a law-and-order perspective and ignored the sordid history of Black men falsely accused of raping white women. She wrote,

Black women have almost unanimously agreed that their liberation as women depends on improvement of life in their communities and cannot be won apart from the liberation of Black men. A movement that does not take this into account will not win Black women.

Angela Davis made the same criticism and described the book as “pervaded with racist ideas.” Rape, Racism is now selling for $20 to $30 online and is used by the Young Democratic Socialists of America in their workshops on sexual violence.

In 1979, STO’s journal, Urgent Tasks, published a two-part article, “Women and Modern Capitalism,” also by Alison, in issues 5 and 6.3 Part One examines the ways capitalism erodes the material basis for women’s oppression by releasing her from the home into the workplace, and offering her birth control and dishwashers.

Alison said that if you didn’t like Part I, you would like Part II, and vice versa. Part II argues that “Male supremacy, despite its diminishing utility for capitalism, has taken on a life of its own.” As men lose their grip on the public sphere, they insist more shrilly on their prerogatives: women owe them sex, sympathy, and status. She explains Marx’s theory of alienation, and describes how the tool-maker is made into a laborer: our ability to work creatively, which distinguishes us from beasts, is transformed into a commodity, becoming an element of the power that suppresses us.4 While women’s status approaches equality in our own communities, there is a countervailing tendency among men to celebrate their sexuality as an act of compensatory consumption, treating women as trophies to be consumed, epitomized by the Playboy Bunny. Alienation gives rise to hedonism. I don’t find this argument convincing; it is a position that contains its own negation — if today’s transformed male supremacy is affective, what’s to bind us to its dictates? Maybe it is all hot air. Nevertheless, her articles were an important contribution and should have opened a debate, but did not.

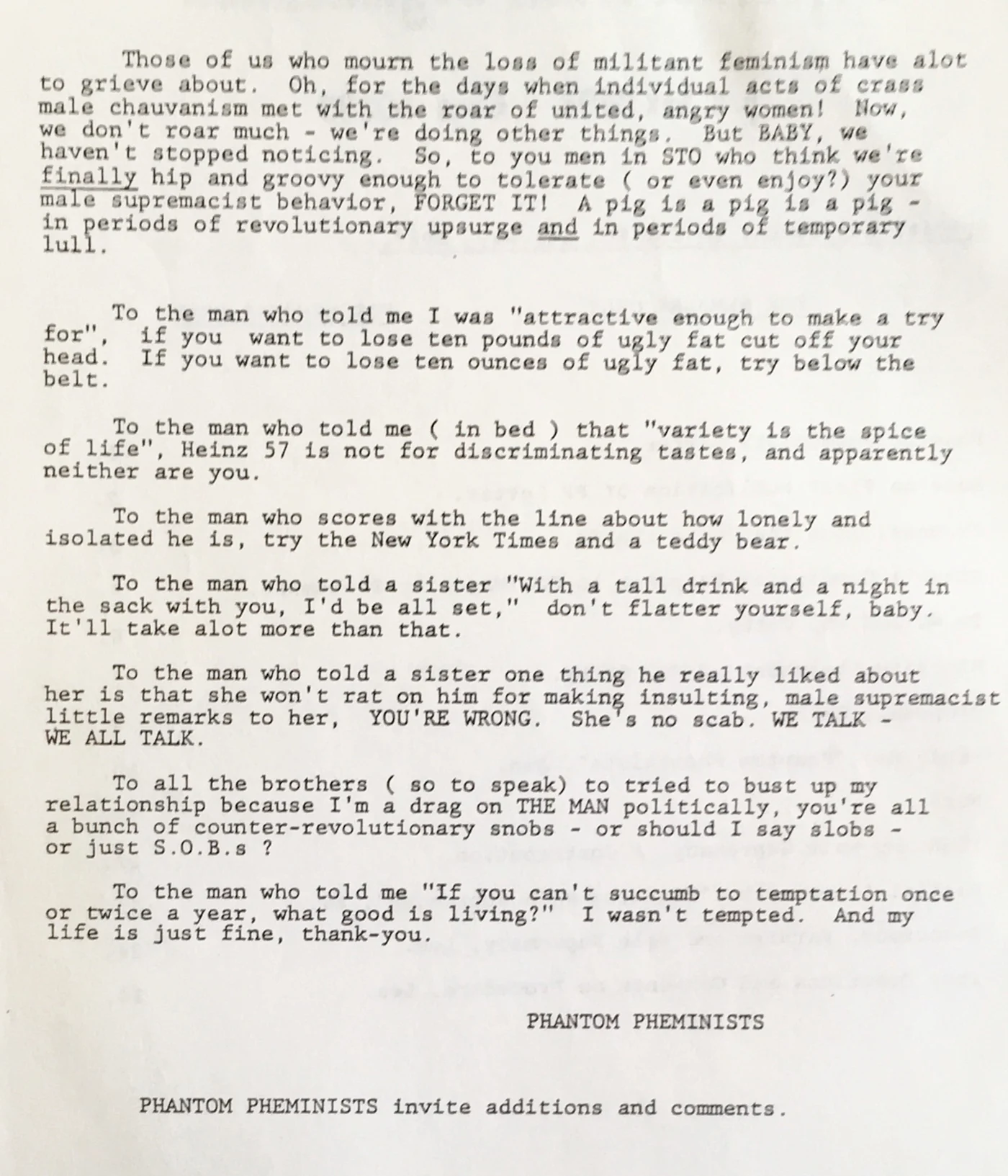

Alison married Noel Ignatin (now Ignatiev) in 1974; by 1980, they were divorced. In 1979, hoping to provoke debate, she published, in the “public” edition of the Internal Discussion Bulletin (IDB)5, a list of sexist comments made by unnamed men in the organization, signing it “Phantom Pheminists”:

Those of us who mourn the loss of militant feminism have a lot to grieve about. Oh, for the days when individual acts of crass male chauvinism met with the roar of united, angry women! Now, we don’t roar much, we’re doing other things. But BABY, we haven’t stopped noticing. So, to you men in STO who think we’re finally hip and groovy enough to tolerate (or even enjoy?) your male supremacist behavior, FORGET IT! A pig is a pig is a pig — in periods of revolutionary upsurge and in periods of temporary lull. To the man who told me I was “attractive enough to make a try for,” if you want to lose ten pounds of ugly fat, cut off your head. If you want to lose ten ounces of ugly fat, try below the belt. To the man who told me (in bed) that “variety is the spice of life,” Heinz 57 is not for discriminating tastes, and apparently neither are you. To the man who scores with the line about how lonely and isolated he is, try the New York Times and a teddy bear. To the man who told a sister, “With a tall drink and a night in the sack with you, I’d be all set,” don’t flatter yourself, baby. It’ll take a lot more than that. To the man who told a sister one thing he really liked about her is that she won’t rat on him for making insulting, male supremacist little remarks to her, YOU’RE WRONG. She’s no scab. WE TALK — WE ALL TALK. To all the brothers (so to speak) who tried to bust up my relationship because I’m a drag on THE MAN politically, you’re all a bunch of counter-revolutionary snobs – or should I say slobs — or just S.O.B.s? To the man who told me, “If you can’t succumb to temptation once or twice a year, what good is living?” I wasn’t tempted. And my life is just fine, thank you. —PHANTOM PHEMINISTS PHANTOM PHEMINISTS invite additions and comments.

This caused a shitstorm. There were three women on the Women’s Commission — the body designated to deal with women’s issues — who had approved publication: Alison herself, Linda, and Cathy. Linda defended the action, while Cathy apologized for its publication, disassociated herself, and said she had not thought it through. Many in the group thought personal relationships off-limits. Many insisted the way to deal with male chauvinism was to develop strong women thinkers and actors. Many, men and women, took a pro-sex position, arguing that “Phantom Pheminists” was prudish and trivial. Many of us were afraid the document would be leaked to the women’s movement and used against STO. The women’s movement had developed a certain amount of legitimate distrust of the Marxist-Leninist left, in response to unprincipled attempts to send secret members into autonomous groups to infiltrate and change their direction and to recruit. Some of us worked closely with socialist feminists doing reproductive rights work and thought that this dirty laundry would make us look bad, especially in the eyes of potential recruits and friendly outsiders.

Alison revealed herself as the author early on, and said the incidents had been reported to her by several women. Most of us had a good idea who the men were. She had succeeded in provoking debate.

The “Phantom Pheminists” episode exposed our lack of clarity on what constituted male chauvinist behavior. Our gatherings were marked by an atmosphere of suggestive banter and remarks about women’s looks. Noel was an inveterate flirt and liked to repeat jokes he heard in the factory, resulting in a stream of off-handed remarks that often referenced sex. Several strived to keep up. Don held aloof. One remark I remember, quoting a fellow worker speaking of women, “If they didn’t have pussies, there’d be a bounty on them.” Another, from Noel, “I wouldn’t fuck her with someone else’s dick.” There was an element of proletarian bravado in all this; if you objected, you were a middle-class prude.

Alexandra Kollontai, a Bolshevik leader, was never mentioned without reference to her lovers, and Lenin’s ménage à trois was referred to frequently. It felt like an all-male workplace, with lascivious pinups next to motor diagrams. Noel’s biographer, Maks Bondarenko, points out that Noel attended an all-male high school and then went to work in nearly all-male factories, “primary breeding grounds for narcissistic masculinities and performative bullying.”6 He also points to “a particular male political subjectivity on Ignatiev’s part, one in which women appear first as romantic or sexual interests, and fellow workers or radicals second.”7

This festival of innuendo was a way of returning to the sensual world from the high level of abstraction that enveloped our meetings. Sitting in a circle and debating theory is not manly. Noel used to say, “An intellectual is someone who can think about something besides sex for more than ten minutes.” Off-color wisecracks were his way of breaking the tension. He did not intend to offend us, he would say it wasn’t personal. But he knew the material was charged, that’s why he used it, and he knew the charge differed for us and him, and he wanted us to rise above it. His assumption that we shouldn’t mind flowed from another assumption, that the male experience was universal. That was never debated.

Noel was arrogant to both men and women. We championed a debating style that was hard-hitting, which many called “male style.” We believed in clarifying differences. Ken was proud of our methods of struggle and our use of emotional, even abusive, language.

Ken focused on form, comparing the anonymous accusations made by the Phantom Pheminists to the FBI’s Cointelpro strategy of sowing discord through anonymous grievances. He pointed out that the FBI had exploited Don’s affair to cause trouble in his first marriage, and showed us the relevant FBI documents.8 Alison argued that anonymity put all the men on notice that such behavior would not be tolerated.

Five women signed a letter, “Fighting Male Supremacy: A Contribution,” repudiating the action of the “Phantom Pheminists”:

Attacks on sexuality, particularly heterosexuality, are not appropriate methods of raising and attacking male supremacy. There is a fine line that can be crossed between sexuality (sexual attractiveness) and male supremacy. Not all sexual advances are offensive to all women even though the line may have been crossed for some.9

The Five Signers found most of the incidents inoffensive. They argued that male chauvinism is inevitable, that personal issues short of physical violence should not be subject to the group’s authority, and that we needed to “…look at the women in STO. Are women encouraged, supported, and pushed to develop? Do we significantly contribute to political discussion? Do we travel and speak as representatives of STO? Do we write? Do we think? Have women in STO changed?”10

This position placed the burden on women to show our impermeability to whatever juvenile noise the men were making. We should despise the tyranny of victimhood and never admit to our wounds. Moreover, we were privileged, white, members of the oppressor nation, and educated; “white woman oppression” was a term of scorn. The Five insisted that instead of whining, we should be training ourselves to compete. “Articulate and advanced women should be helping less developed women develop skills and confidence. The most effective way to challenge male supremacy in STO is to develop strong women thinkers and actors.”

It was suggested, for example, that we team experienced writers with less experienced ones on assignments.11 I don’t remember whether we did or not, but I never teamed with anyone in STO to write, although I frequently worked with other writers doing local, non-STO work. I did not learn to structure an argument until many years later at the university; all of my articles published in Urgent Tasks needed editing they didn’t get. None of the editors — and I was frequently an editor myself — offered that sort of support.12

Lee wrote an article, “Democracy, Marxism and Male Supremacy,” arguing that, given the differences among the women, judgments regarding oppression should be made by the oppressed group as a whole (her emphasis). She accused Alison of celebrating her victimhood, and not seeing herself as both a victim and a subject capable of resistance:

It is not the responsibility of oppressed groups to raise the consciousness of their oppressors. The responsibility of oppressed groups is to become free of their oppression… [T]he oppressed/victim, believing that she is a victim, will behave like a victim. When she behaves like a human, she is breaking her oppression/victimization.13

It’s up to us to be the change we imagine: don’t show weakness. Male supremacy could only be overcome by women acting on their own, alone; there was no need to bother the menfolk. Strong women could brush off belittling remarks and rape jokes.

Lee was shrewd; she learned to write, and was a formidable spokesperson. She did a marvelous line drawing illustrating Hegel’s “Lordship and Bondage” structure; we used it as the cover for Urgent Tasks #7, which contained STO’s original study guide for Marxist dialectics, titled “How to Think.” She had recently written an article analyzing dual and trade union consciousness for a debate with the International Socialists. Lee argued against the notion of workers reacting to capitalism as an external force, reflexively, without indicating their own capacity for growth, for creating a new world among themselves. The worker whose consciousness she described was male: “This acceptance by the worker of himself as a wage-earner…”14

Alison and Linda responded to the Five with a paper, “In Defense of Feminism,” which argued that the point of the action was to encourage women to express their anger and report sexist behavior, which could then be dealt with collectively.15

By contrast, the approach of the Five Signers was individual and not collective: they wanted the men to be dealt with personally, in private, if touching on intimate matters. The Five Signers pronounced the incidents described by the Phantom Pheminists as trivial. They repudiated the suggestion that women were weak and in need of protection and so they made it harder for women to raise objections to abusive males in the future.

Alison responded that, just as when the foreman harasses the worker in the factory, although each individual act might be trivial, the cumulative effect matters.16

Alison and Linda, who were the initial champions of Phantom Pheminists, wrote, “We do not think public action implies weakness,” adding that, “…since sexual relations are where a lot of male chauvinism plays out, we consider it quite legitimate for women to hold men accountable in these areas and to raise these issues publicly if they choose.” They argued that, in societies where men and women are not equal, sexual relations cannot be separated from differential power in the world. They analyzed the statement, “attractive enough to try for,” and pointed out that the man was asserting his right to rank women by their looks while standing apart.17 They also pointed out that Alison was among the strongest and most articulate women in STO, yet this did not protect her from sexist remarks. Being strong was not enough.18

Alison and Linda wanted a women’s wing that would combat male misbehavior; they were not likely to get it. Instead we debated the issues in the pages of the Internal Discussion Bulletins and in a Women’s Wing meeting held in Chicago in early July.

Cherie described an incident with Noel and Ed that verged on assault. They had been joking about what men said to women in the plant: “With a tall drink and a night in the sack with you, I’d be all set…” and turned to Cherie, who was standing nearby, and repeated the line. She laughed, not knowing what else to do. This was after Noel had commented on her “bumps” — breasts — on a previous occasion, and she was uncomfortable. Then Noel held her arms and Ed poked at her stomach, while the two of them teased her that she wouldn’t rat on them to the Women’s Commission. When this came up in a meeting, Noel said he would have stopped immediately if he’d known she objected, but she seemed to be enjoying it. Cherie had been stunned. She put the incident in the context of every woman’s concern to protect herself from rape, which Noel would have laughed off as preposterous. But that was consistent with his refusal to admit that historical abuses against women had anything to do with him.19

The issue of STO’s relationship to children came up. Most of us were childless, and Noel once declared, “Marx let his children starve.” Alison had made an earlier criticism of the central committee for excluding her from a meeting by not helping with their daughter, then an active toddler. The central committee refused to accept the criticism.20 These conflicts came up in every branch. Some of the women in Davenport acknowledged the need for collective childcare, although I don’t recall anyone in Davenport having kids. Shortly before the appearance of the Phantom Pheminists, the Women’s Commission asked members to comment on having children while in STO. One member suggested that while children could be a “hindrance to political work,” they were essential. He felt that many in STO viewed parenthood as “bourgeois” and “self-indulgent.” The wife of a member complained of a “double standard” regarding meeting attendance, where child-caring responsibilities were looked down on. Another member concluded that, “...people’s treatment in STO of families has been pretty dismal.”21

Alison wrote some thirteen densely argued pages. She described STO as “uniquely untouched by the New Left and the feminist movement,” although STO was not unique. She described the “sad state” of the organization: where Noel and Ken “proclaim they can’t or won’t ever change,” and Noel “…flaunts his male chauvinism and belligerently challenges anybody to try to stop him…” Couples broke up and women disappeared; women on the national committee remained silent; women could not be found to debate intellectual issues; and a “smart, articulate, and committed woman” (me) refused to write for Urgent Tasks, since all I ever got was criticism. Women were beaten by their sons and partners without anyone raising a cry, and “... it becomes an issue what man will travel to Europe with what other man to represent STO based on who will ‘get all the women.’”22

Alison described Noel’s resentment of their daughter and refusal to live in a “child-centered home.” He had accused her of being too wrapped up with mothering, and blamed their problems on her being lazy and not sufficiently “political.” He had taken on additional tasks six weeks after the girl’s birth, including preparation to teach the political economy class. She described the aftermath of the accident in England, when Noel, confused at British traffic, turned into an intersection in the face of an oncoming car. Noel and the baby were unhurt, Alison suffered cracked ribs and a concussion. Noel jumped out of the car to talk with the other driver, who was unhurt. Alison and her daughter flew back to the states and spent a month recuperating, while Noel continued to tour Europe.23

Upon their return, the plan had been for Noel and Alison to settle permanently back east. Noel came back and was cold and impatient. Alison was pregnant, and he warned her that if she had the second child, he might not stick around. Noel, Carole, Don, and Ken — the “heavies” in the group — already thought she was doing less political work and spent too much time being a mother; they insisted she have an abortion.24 Alison had produced Part I of her article, “Women and Modern Capitalism” during the six months after giving birth, while aspersions of laziness were being thrown at her.

She did have an abortion, not to save the marriage but because it was over, and she did not want to be the single mother of two toddlers. She moved back to Chicago and plunged through snowdrifts, looking for housing, with a twenty-pound one-year-old in her arms. Noel followed, but their reconciliation was brief.25 A year later, Alison was with someone else, who joined STO, and they had another daughter. A year after that, they left STO.

Alison explained the context of the Phantom Pheminist incidents involving Ken. While her partner was out of town, Ken had showed up, tried to take Alison to bed, and when she turned him down, declared, “If you can’t succumb to temptation once or twice a year, what good is living?” She described her one sexual encounter with Ken, six months before, as “degrading.” It occurred in the context of a long friendship, characterized by mutual respect and a certain amount of sexual tension. They had frequently shared motel rooms while traveling on STO business, as we all did. She had slept with him once, while her marriage to Noel was crumbling, and was startled at the cold and mechanical nature of his love-making. The next day, he asserted that the point of having sex was not emotional closeness but to get off. Alison declared his separation of sex and intimacy to be male chauvinist in itself. “When a man tells a woman he is fucking her just to get his rocks off, he is not talking about sexuality, he is talking about power.” This was another point the women never debated. The day after Ken’s last seduction attempt, Alison sat down and wrote out “Phantom Pheminists.”26

We could not judge whether anyone’s behavior was male supremacist because we had no theory of gender oppression. The elephant in the room was the war between the sexes, as Noel called it. Each of us had a tangled history of seduction and power that no one could face, least of all collectively.

Masculinity is fragile, it has to be constantly defended; but there is no escape from a woman’s body. I could never be neutral, just another student, another comrade. My body determined how I was seen. I think that the sex-positive attitude of the five signers of “Fighting Male Supremacy” did not take into account the terrible weight of everyone else in the room. In every bed, there are six: the couple, and their parents. In every seduction, there is everyone who has rejected and pursued us, and there is a calculation of relative worth — who is better looking, who has better housing, who is more sought-after.

There was the question of whether the organization should intervene, which most people were against. But we had already passed a couple of rules. The Anderson rule stated that anyone in a monogamous relationship should inform their partner if they intended to stray. (Cherie Anderson’s partner had taken up with someone else.) In April 1978, the women’s wing had announced that any woman who allowed a man to beat her should be expelled. This followed an incident where a woman who had been married to a male “heavy” got involved in a relationship that included physical abuse. She said that the mental abuse in her marriage was worse than anything that came after.

The rule around monogamy was tricky. We were a cadre organization, accountable to each other. Commitment to the group overrode commitment to family and spouse. A lot of spouses who did not join were left behind. It was better to be with someone in the group but that put us in competition with one another for partners. Affairs among us threatened our stability and took up time that could be spent on work. Most of us were under forty, and many couples were realigning.

Everyone, except Ken, agreed that male supremacy/chauvinism permeated the group. The question was whether to challenge the men directly, or focus on developing women as critical Marxists; no one suggested we could do both. We did, before and after this crisis, develop women as thinkers — we developed ourselves. The women who had been willing to confront individual men directly left the organization within a year: Linda, Alison, Cherie. Many of the women who stayed were explicitly against challenging the men directly. I don’t recall any men speaking directly to this point.

Broad disagreements about the nature of romantic and sexual relations emerged, making an evaluation of male chauvinism within one-on-one relationships tricky — should it be a concern of the organization? That question was never resolved.

We decided to discuss the nature of male supremacy in an upcoming meeting of all the women, already scheduled for the near future. Below, I have summarized a number of positions as recorded in the notes from that meeting, published in the members-only Internal Discussion Bulletin in December 1980.27 The arguments on both sides show a high level of sophistication.

We began by affirming our decision not to participate in work against violence against women after a debate between Alison and Marcia, who worked at a rape crisis line. We discussed our continuing work in reproductive rights. We talked about the autonomous women’s movement. Carole argued that the women’s movement does not see the centrality of class. “The women’s movement has penetrated the working class, but the working class has not penetrated the women’s movement.” Lee announced that women in STO had progressed beyond the need for consciousness-raising.28

Next on the agenda was, “What is male chauvinism and how should we deal with it in STO? Does STO facilitate the political participation of women?” Carole remarked that some men flaunt male chauvinism. Several women remarked on the chronic need to be competitive and aggressive. They also said that women tolerate male chauvinism and don’t support women who bring it up. Carole brought up an interesting point: sexual intimacy is as far as it gets from capitalist alienation, and hedonism can be both reactionary and progressive, even liberating. This was as close as anyone came to addressing the issues that the “Phantom Pheminists” had raised. I argued that the issue of male chauvinism was inseparable from that of informal decision-making and the lack of communication from leadership, which were problems of accountability and, ultimately, of power. I said that I would be willing to lose both Ken and Noel. Marilyn claimed that her relationship was equal, and she did not understand the power differential.29

Alison said she had acted from anger and was paying a steep price for handling these situations as an individual. Cherie said that she was treated less seriously since separating from her partner, and that the women in Davenport had not been sisterly but destructive towards her. She left the organization within a year. Carole and Pam pointed out that we women distrusted each other. This was obvious. Some women argued that the Phantom Pheminists should have obtained agreement from all the women before proceeding, as they had found the content “embarrassing.”30

Carole argued that when the women’s movement organizes around male chauvinism, it leans towards separatism. In her view, Alison, Linda, and I lacked a working class perspective. Alison and Linda did not take class seriously and had sidelined Cathy on the Women’s Commission. Alison had stopped doing “drone work” and only did theory, leaving her, Carole, with more to do. She also criticized Alison for wanting folks who were “articulate” to serve on the National Committee. She claimed to be “shocked” by the “Phantom Pheminists,” that they did not care about other women and that they showed that the concerns of women in production were not taken seriously by “intellectual” women.31 This was a serious accusation. Carole backed down, denying that she was class-baiting; but it revealed a rift that I still find bewildering. What were those concerns that “Phantom Pheminists” belittled? How did they express anti-working class sentiments? Separatist sentiments? This was never debated.

Alison and Linda and, to a lesser extent, I were accused of being middle-class intellectuals who disrespected working women. Janeen said that our disagreements over what was male supremacy were related to differences in class and education — in other words, our concerns were middle-class. This reminded us of Ken’s assertion that support for an autonomous women’s movement necessarily led to Gloria Steinem, the National Organization of Women, and the Equal Rights Amendment. Is this because it would necessarily be a cross-class movement, the same way nationalist movements are? Marilyn said, during the discussion of the functioning of the Women’s Commission, that she did not “see criticism of men as the way to change STO or society.” Then how? Many of the women were adamant that it was up to us to be strong and ignore boorishness.

All this was necessary preliminary work that could have led to a clarification of our differences, if our intention had been to imitate other STO debates. This is where it ended, while we were just getting started. We had to go deeper.

I wonder what Carole really thought. I remember her playing the middle, trying to hold the group together. STO was led by theory, and that was the purview of Don and Noel. Ken had a big presence, but he was not in Chicago, nor was he an organizational force. Carole was part of the inner circle. She was warm and gregarious, where Don was awkward; she acted as our social glue and made sure we ate salads. She never had children; was she jealous that Alison had a baby? Her complaint that Alison was slacking got conflated with class resentment. Not long after the “Phantom Pheminists” episode, Don had an affair with Janeen and two marriages broke up. I wonder what Carole thought then.

I had not slept for the three nights before that meeting, wracked with guilt over my affair with Noel two years before. Alison was losing the battle she opened with “Phantom Pheminists,” and I needed to tell her. At the last minute, after the meeting, I blurted out to Alison: “I had an affair with Noel that lasted almost a year.”

Another shitstorm broke out. Alison had suspected but she hadn’t known, nor for how long. Ken insisted that the Women’s Commission draft formal charges, although that had not been Phantom Pheminists’ intention. Charges were brought against Noel, and me, and Ken, who knew about the affair, based on the Anderson rule, that folks in monogamous relationships had to inform their partners if they trespassed. The Women’s Commission, now composed of Maryon, Marcia, and Linda, was assigned to examine the evidence. With this, the whole business refocused on Noel and our affair, rather than the bad jokes, marital tensions, or the tendency of most of the speakers and thinkers to be men.

Ken continued to bluster in his own defense. I had told Ken about the affair in a moment of self-pity; Noel was angry, but it left him free to confide in Ken, too, and so Alison accused Ken of concealing information from her. Ken insisted on the need to protect my confidence. Alison was forced to drop the charges against Ken. Alison and Ken exchanged a series of letters that showed both the depth of their friendship and their anger. I wrote an abject self-criticism and was exonerated. Noel apologized to Alison for the affair but claimed that Alison had turned to child-raising and away from politics and that his sex drive was greater than hers. When she listened to the recording of his interview, Alison accused him of providing a male supremacist defense.

The Women’s Commission recommended sanctions against Noel, to be voted on first by the women’s wing and then by the whole group. Noel could be barred from the National Committee and kept from international travel for up to a year. He was accused of blaming the failure of his marriage on Alison’s being rich, bourgeois, and uninterested in politics after their daughter’s birth. He had promoted the perception of me as “promiscuous, neurotic, and ambitious” while in a relationship with me, and encouraged me to have other affairs. We all agreed to drop this charge. He was accused of promoting divisions among STO women and promoting differences between Alison and Ken, by keeping secrets that affected them.32

The investigators reported that Noel and I had a year-long affair. Noel was accused of hiding behind politics, since we went to the same meetings, then he drove me home and came upstairs. Noel insisted that Alison had become disinterested in politics, which Carole and Don confirmed. Ken did say that Alison was rich and bourgeois. Alison was obliged to defend her decision to work a thirty- and not forty-hour week, so she could spend time with her daughter, and her small inheritance, now smaller since she and Noel had lived on it since Noel was unemployed all this time. She was enraged that Noel had taken me out for dinner on her money. Noel resented the time he spent with his child; he had been unrealistic about parenting. Noel had said both positive and negative things about me, and had trashed me to Alison. Noel did not talk about Alison to me. Noel asserted his sexual needs, frustrated by Alison’s mothering.33 These interviews were two years after the affair.

All this was laid at the feet of the membership. On December 1, 1980, Alison sent a letter resigning from STO on the letterhead of her law office. Linda also resigned, citing poor health.34 These two had been the Phantom Pheminists’ outspoken defenders.

The women voted first. Four women abstained, since we had no agreement on what male supremacy was. Two women voted consistently to absolve Noel of all charges, these were presumably the two of the Five Signers who did not abstain; two others frequently absolved Noel. Adding them to the four who abstained, only a slender majority voted against Noel.35

The January 1981 National Committee again focused on the charges against Noel. We discussed whether or not he had changed, as if we knew. Noel claimed to have assimilated “what is valid in the criticism” and promised to make an act of will to treat women better, to listen to women and incorporate our criticisms in his behavior. But what did that mean — he would stop flirting, being flippant, making sexist jokes? He claimed to be deeply shaken. “I don’t believe that my mistakes and failings in dealing with women are so deeply rooted and peculiar to myself that they cancel the other contributions I make.”36

Ken insisted that “we are all small, weak, and frail — society fucks us all up,” and that we should not judge one another. We should emulate the good characteristics of (male) leaders, who were heroes despite their weaknesses. The standards being set for Noel would exclude all male revolutionary leaders. Should we do without C.L.R. James?37 I replied that behind each one of those heroes are silent women. Arrogance and flippancy are harmful because society has made us vulnerable and burdened; admitting to being vulnerable should not expose us to scorn. We function despite our burdens, but this one should be removed.38

Following a vote of the entire organization, Noel was removed from the National Committee and subjected to supervised travel for a year.

STO never developed a position on patriarchy, we were not feminists. We did no systematic study of gender together, nor do any of the chapters of our Dialectics class acknowledge gender. We assigned Wages for Housework by Maria Rosa Della Costa to Session Two of the Political Economy Study and included one question that referred to reproductive labor out of six sessions.

To do feminist theory was to pose a problem that no one was pressing to solve; it was not an urgent task. To focus on women’s issues — gender oppression being a women’s, and not a men’s, issue — would isolate us from the real life of the organization. No one, except Alison, did theory regarding women. She bore the heavy lifting for years.

Several folks in their comments on the ballot regarding Noel remarked that they were sure he was a sexist but not for any of the reasons laid out in the charges. Someone said the atmosphere in our meetings reminded him of Charles Bukowski, the underground writer whose machismo was both a satirical pose and a rant against respectability, often depicted as Woman, especially among the beatniks — the censorious wife, enforcer of domesticity and enemy of fun.

The battle opened by “Phantom Pheminists” got deflected into the evaluation of specific events. We never addressed the tone of the banter, or the ethics of our relationships, or the way women left the group when couples broke up, or the heavy shadow of the masculinist old left, or our top theoreticians all being men, or what we would today call “micro-aggressions.”

We could not handle seeing the personal as political; had we attempted in earnest, it would have provoked a crisis and gotten in the way of our work. Most of us were working full-time jobs while doing full-time political work — a double shift. We reproduced millennial patterns and refused to view ourselves collectively through a gendered lens.

Not having theory beyond a critique of whiteness in the women’s movement — and where did we not critique whiteness? — made it harder to look at ourselves historically. It was too complicated, too primordial, and could be deferred. Grappling with sexism on a world historic scale would have given us — the women — an edge, but it would have destabilized us. We had no unity, many of us preferred an alliance with our menfolk to fictitious solidarity among women. We could not determine when it was history that weighed on us and when it wasn’t.

Notes

1. The symposium can be found online here.↰

2. The text can be found online here.↰

3. I could not locate Part One online, although I have a photocopy. Part Two is online here.↰

4. Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, Foreign Languages Publishing House, first impression, 68–81.↰

5. We had a members-only IDB and another we could share with allies and friends. This was before the internet; both IDBs were compiled and mailed to each member, on paper, at considerable cost for postage and someone’s time. I believe the photocopies were “donated.” ↰

6. Maks Bondarenko, The Heartbreaks of an American Communist, Unpublished Masters Thesis, City University of New York, 2025, 108.↰

7. Bondarenko, Heartbreaks, 42.↰

8. Ken, “Reply Re: ‘Phantom Pheminists,’” in Special Supplement to IDB #16, May, 1980, 10. Private collection of the author. ↰

9. Cathy Adolphson et al., “Fighting Male Supremacy: A Contribution,” in Special Supplement to IDB #16, May, 1980, 19. Private collection of the author.↰

10. Adolphson et al, “Fighting Male Supremacy,” 19. ↰

11. Adolphson et al, “Fighting Male Supremacy,” 19. ↰

12. I always wrote but I did not learn to structure an argument until twenty years later when I went to the university.↰

13. Lee Holstein, “Democracy, Marxism, and Male Supremacy,” in Special Supplement to IDB #16, May, 1980, 24. Private collection of the author.↰

14. Lee Holstein, “Working Class Self-Activity: A Response to Kim Moody,” in Urgent Tasks No. 9, Summer, 1980. Online here.↰

15. Linda Phelps, Alison Edwards. “In Defense of Feminism: A Response to ‘Fighting Male Supremacy,’” in Continuation of Special Supplement to IDB No. 16, May-June, 1980, 1. Private collection of the author.↰

16. Alison Edwards, “Some of the Events Behind the Phantom Pheminist(s) Action,” in Continuation of Special Supplement to IDB No. 16, May-June, 1980, 13. Private collection of the author.↰

17. Linda Phelps, Alison Edwards. “Some Comments and Questions after Reading Lee’s Paper,” in Continuation of Special Supplement to IDB No. 16, May-June, 1980, 6. Private collection of the author.↰

18. Linda Phelps, Alison Edwards. “Defense,” 1.↰

19. Cherie, “Is STO Really Serious about Fighting Male Supremacy?????,” in Continuation of Special Supplement to IDB No. 16, May-June, 1980, 33. Private collection of the author.↰

20. Alison, “Criticism of the Chicago Branch and CC,” in Secret Supplement to IDB No. 15, February, 1980, 19. Private collection of the author.↰

21. Michael Staudenmaier, Truth and Revolution: A History of the Sojourner Truth Organization, 1969-1985, AK Press, 2012, 213-14.↰

22. Alison Edwards,“Some of the Events Behind the Phantom Pheminist(s) Action,” in Continuation of Special Supplement to IDB No. 16, May-June, 1980, 13. Private collection of the author.↰

23. Edwards, “Events,” 13.↰

24. Edwards, “Events,” 13.↰

25. Edwards, “Events,” 13.↰

26. Edwards, “Events,” 13.↰

27. “Minutes of the Women’s Wing Meeting,” Special Women’s Commission IDB No. 20, December, 1980. Private collection of the author.↰

28. “Minutes of the Women’s Wing Meeting.”↰

29. “Minutes of the Women’s Wing Meeting.”↰

30. “Minutes of the Women’s Wing Meeting.”↰

31. “Minutes of the Women’s Wing Meeting.”↰

32. “Sanctions against Noel Ignatin for Male Supremacist Behavior,” Special Women’s Commission IDB No. 20, 1, December, 1980. Private collection of the author.↰

33. “Report on Investigation of Charges of Male Supremacy against NI,” Special Women’s Commission IDB No. 20, 6, December, 1980. Private collection of the author.↰

34. Letters, Special Women’s Commission IDB No. 20, 1, December, 1980, 16-17. Private collection of the author.↰

35. “Sanctions”↰

36. Noel, “Statement on Charges and Proposed Sanctions,” Secret Supplement to IDB No. 21, January, 1981, 3. Private collection of the author.↰

37. “Minutes from NC Discussion of Sanctions against Noel,” Secret Supplement to IDB No. 22, March, 1981, 18. Private collection of the author. ↰

38. Beth, “On Sanctions,” Secret Supplement to IDB No. 22, March, 1981, 25. Private collection of the author.↰