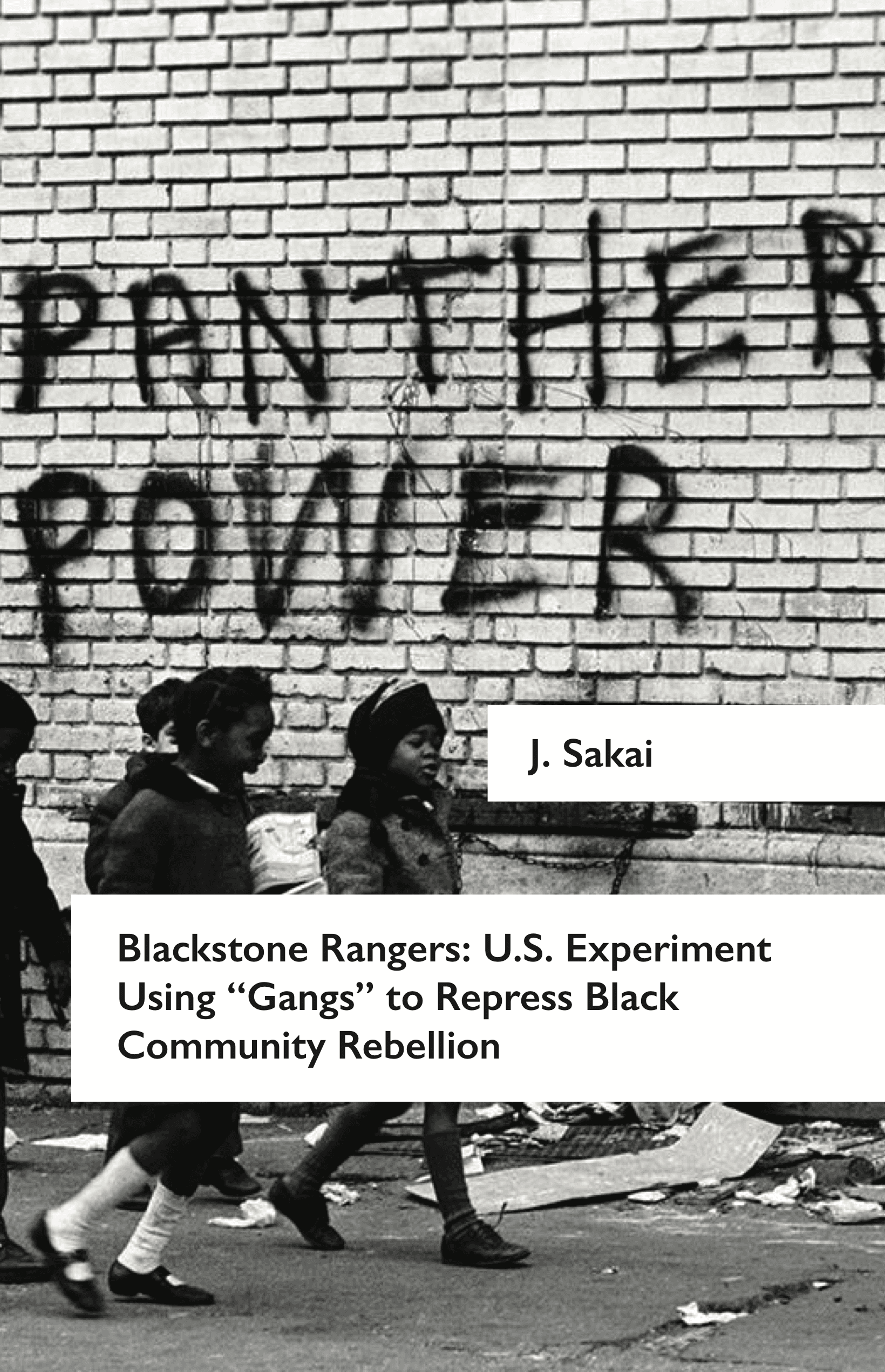

Blackstone Rangers: A U.S. Experiment Using ‘Gangs’ to Repress Black Community Rebellion

J. Sakai

Our purpose in reprinting Sakai’s piece is to share an often neglected episode of Chicago history as an entry point into theoretical and practical questions about local insurrectionary potential. The story he shares is the following: in the late 1960s, members of the city’s Civil rights movement sought to ally themselves with the most powerful black street gangs in Chicago. Together they secured a $927,000 annual grant through the federal Office of Economic Opportunity. The Chicago police department eventually got involved and worked with liberal ‘community leaders’ to use the gangs as a counter-insurgency force. Black gangs – especially the Black P. Stone Rangers – were regularly relied upon to suppress rioting and revolutionary organizing in their territories. […] [T]he question, for us, is what strategy to take with respect to that triangular counter-insurgency apparatus made up of Leftism, police, and gangs? How to navigate their counter-insurgent history while also recognizing that there are fragments of the left and the gangs that are irreducible to the existing order of things? The past thirty years have seen the police pursue a strategy of ‘decapitation’: going after shot-callers and watching like vultures as the gang hierarchies implode into organized disorder. The resultant genocide is the cheap price of the boost in police legitimacy, as citizens cry out for protection from the multiplication of gang wars. The civil rights campaigns and ‘community organizations’ of the Left, meanwhile, have fragmented and multiplied into an expansive N.G.O. network as its more revolutionary tendencies have retreated to ‘abolitionism’. We are familiar with peace-policing in the streets, but rarely do we reflect on how to organize ourselves vis-à-vis the aforementioned triangle outside of head-to-head confrontations with the cops. More generally, we lack a contemporary political analysis of the counter-insurgent shape of power relations that has emerged through the Left-cop-gang triangle in Chicago. Despite its predominantly class-based analysis, we hope that Sakai’s text can provide some orientation to that end.