Refusal Requires a Guerilla Mentality

Rudi Dutschke and Hans-Jürgen Krahl

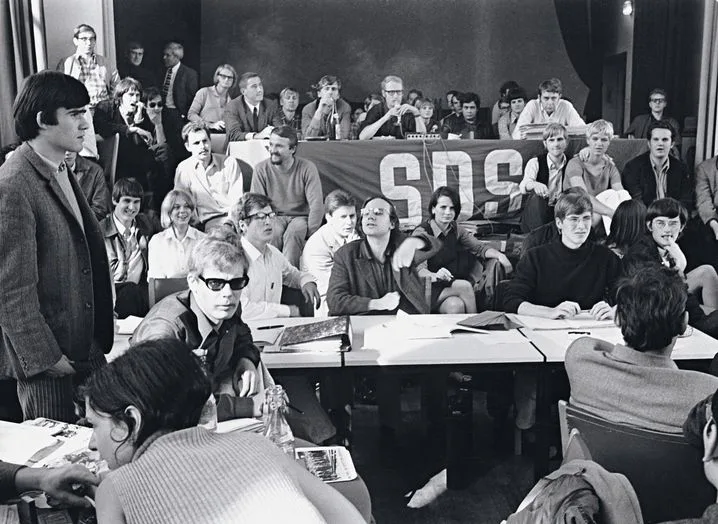

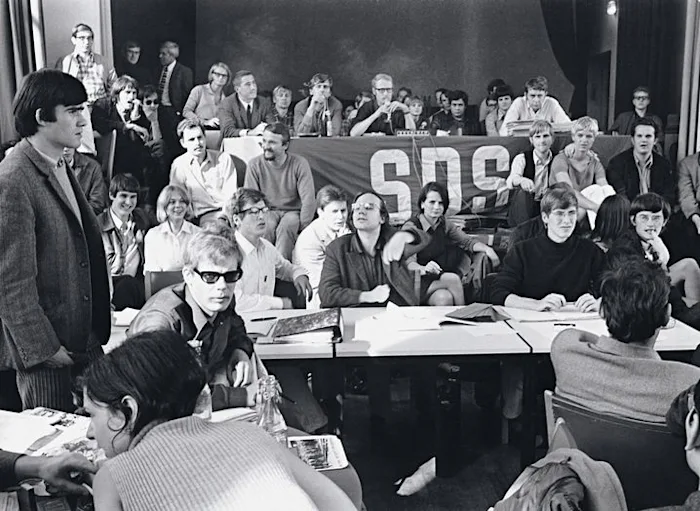

The following organizational speech was delivered by Rudi Dutschke on September 5, 1967, at the 22nd delegates’ conference of the Socialist German Students' Union (SDS).1 Written together with Hans-Jürgen Krahl, it boldly announced an anti-authoritarian breakaway from the traditionalist wing of the organization, immediately provoking fierce controversy.

Rudi Dutschke (1940-1979) was perhaps the most famous and radical figure of the German New Left, the student movement and its “extra-parliamentary opposition.” Almost none of his hundreds of writings or speeches currently exist in English. Dutschke was shot in April 1968 on the streets of Berlin, and died a little over a decade later as a result of the injuries.

Hans-Jürgen Krahl (1943-1970) was a militant, a radical intellectual, a student (and critic) of Adorno in Frankfurt, a member of SDS, and author of the posthumous collections, Constitution and Class Struggle and The End of Abstract Labor. He died tragically in a car accident at the prime of his life.

Other languages: Deutsch, Türkçe

The two central political events that dichotomously polarized political activity within the student union since the last delegates' conference were the formation of the Grand Coalition and the political assassination on June 2 in Berlin.2 For the first time since the split from the SPD [Social Democratic Party of Germany], the question of organization is posed as a current political issue within the students’ union. Depending on which of these events was assigned political importance, factions tended to be formed, characterized by the objective intention to concretize theoretical opinions into practical-political struggles.

The possible organizational consequences of this were described, for instance, by the National Executive Committee from the experience of the protest movements, especially those of young people, in vague and empty terms, as a “formally loose organization working in public with uniform content” and discussed in Berlin under the title of the counter-university and “institute associations,”3 while for other groups the formation of the Grand Coalition provided an occasion for a repeated attempt at a rallying movement of socialist groups and small groups. Moreover, the relevance of the organizational question became all the more acute for some SDS groups after June 2, as they had to practically experience their organizational inadequacy. The unprecedented broadening of the anti-authoritarian protest after June 2 was no match for the outdated organizational structure of the SDS, which was still oriented toward the SPD. The spontaneity of the movement threatened to paralyze the largest groups organizationally. Their political behavior therefore appeared to be mainly reactive, and attempts at political leadership were largely helpless.

The phenomenon of falling growth rates in the most important indicators of economic growth, which is immediately visible in the present, cannot be superficially explained by mere cyclical fluctuations. The fundamental factors of economic growth are constituted by the quantitative and qualitative determination of the structure of the labor force and the state of development of the means of production depending on it. The interaction of these two elements constitutes the "objective trend line" (Janossy) of economic development. […]

On the basis of an excellent structure of the labor force in West Germany (influx of skilled workers from former German eastern territories and later from the German Democratic Republic until August 13, 1961), it was thus possible for a long rise mediated by American capital to fully exploit the existing level of the labor force and the productive machinery it set in motion. In addition, the impression of an economic miracle could only arise in West Germany “because not only were the consequences of the war overcome, but also the backlog created between two world wars was made up.”

In the course of the prosperous [post-war] reconstruction period, with its high growth rates, high subsidies were wrested from the "weak state" through pressure from political and other interest groups, which the ruling oligarchy was quite able to cope with under the conditions prevailing at the time.

At the end of the reconstruction, that is, the period of entry into the trend line [of economic development], the subsidies appear as additional, mostly unproductive expenditures, as dead weights dangerous for the further development of the economy, as social faux frais, "dead costs" of capitalist production.

The dead weight of the interest groups within the system of interest democracy cannot be easily dismantled in the still pluralistic society, but had to be brought under control at the end of the reconstruction. Thus the concepts of rationalization, formation and ultimately "concerted action" emerge. The various "reform attempts" of the system in the present period should be understood as attempts of capital to adapt itself to the changed conditions in terms of domination and profit.

The most striking phenomenon of the present period of economic formation is the increase of state intervention in the real production process as a unity of production and circulation. This total complex of state-society economic regulation forms a system of integral statism4 which, in contrast to state capitalism, on the basis of maintaining private disposal of the means of production, eliminates the laws of capitalist competition and establishes the formerly natural equalization of the rate of profit by a state-society oriented distribution of the total social mass of surplus value.

To the extent that, through a symbiosis of state and industrial bureaucracies, the state becomes the total social capitalist, society coalesces into the total state barracks, and the operational division of labor tends to expand into a total social one. Integral statism is the completion of monopoly capitalism.

Extra-economic coercive violence gains immediate economic potency in integral statism. Thus it plays a role for the present capitalist social formation, a role that it has not played since the days of primitive accumulation. If in that phase it brought about the bloody process of the expropriation of the masses, which in turn brought about the separation of wage labor and capital in the first place, according to Marx it is hardly used in established competitive capitalism.

For the objective self-movement of the concept of the commodity form, its value constitutes itself into the natural laws of capitalist development to the extent that economic violence is internalized in the consciousness of the immediate producers. The internalization of economic violence allows a tendential liberalization of state and political, moral and legal rule. In the current crisis, the inherently produced crisis condition of capitalist development problematizes the internalization of economic violence, which, according to the interpretation of materialist theory, has two solutions. On the one hand, the crisis facilitates the emergence of proletarian class consciousness and its organization into material counter-violence through the autonomous action of the self-liberating working class. On the other hand, it objectively compels the bourgeoisie to resort to the physically terrorist coercive power of the state in the interest of its economic power of control.

Capitalism's way out of the world economic crisis in 1929 was based on its fixation on the terrorist power structure of the fascist state. After 1945, this extra-economic coercive violence was by no means dismantled, but was psychologically implemented on a totalitarian scale.

This internalization included the disavowal of manifest internal repression and was constitutive of pseudo-liberalism and pseudo-parliamentarism, albeit at the price of the anti-communist projection of an absolute external enemy.

West Germany’s "policy of détente"5, which arose from a changed international constellation, helped to accelerate the process of decomposition of militant anti-communism, especially at the end of the reconstruction period. The manipulatively internalized extra-economic coercive power constitutes a new quality of naturalness of the capitalist system. However, an intervention in the natural laws of capitalist development would only be conceivable in a meaningful way if it structurally altered the objective valorization process of capital. Without this assumption, the critique of the system of manipulation would remain mere cultural critique and the one-dimensionalization of all areas of society, namely the leveling of the scientific differences of superstructure and base, state and society would remain accidental. We only arrive at an economy-critical [ökonomiekritische], materialist perspective, provided that the relation between value and exchange value, the sphere of production and the sphere of circulation, are also included in the global one-dimensionalization of society.

So the question arises: how does the superstructure — extra-economic violence of the state, law, etc. — as an institutional system of manipulation fit into the substance of commodity production, i.e, abstract labor itself? Abstract labor, the substance of value, refers to the relations of production of isolated individuals working privately in a division of labor. Due to their isolation in production, they are forced to sell their products on the market as commodities, i.e. the social intercourse of producers among themselves is not established in production itself, but in the sphere of circulation.

With the development of monopoly capitalism, the tendency towards a progressive liquidation of the sphere of circulation emerges, highlighting the possibility of an abolition of abstract labor. Marx hints at this with his analysis of the joint-stock company when he refers to it as the social capital of directly associated individuals. Extra-economic coercive violence, the state and other superstructural phenomena intervene in commodity circulation in such a way that abstract labor is artificially reproduced through a gigantic institutional system of manipulation.

Such phenomena also intervene in the production of the commodity labor power. When the technical progress of the machine potentially abolishes labor but actually abolishes workers, and when a situation arises in which the rulers must feed the masses, labor power as a commodity tends to be replaced. The wage-dependent can no longer even hire themselves out, the unemployed no longer even have their labor power as a commodity. An indication of this lies in the fact that, at the end of the reconstruction period, structural unemployment can no longer be analyzed in connection with the functional definition of the reserve army.

This tendency can only be understood in the context of a constellational change in the relation between dead and living labor brought about by technical progress toward automation. As Karl Korsch and Herbert Marcuse indicated with reference to Marx, this constellational shift means that it is no longer the law of value, objectively enforced labor time, that provides the standard of value, but the totality of machinery itself.

These hypotheses have fundamental implications for the strategy of revolutionary action. Due to the global one-dimensionalization of all economic and social differences, what was at one point a practically justified and correct Marxist critique of anarchism — that it was a voluntaristic subjectivism, that Bakunin relied on the revolutionary will alone, and that it disregarded economic necessity — is now obsolete.

If the structure of integral statism, through all its institutional mediations, represents a gigantic system of manipulation, this produces a new quality of suffering of the masses, who are no longer capable of outrage on their own. The self-organization of their interests, needs, and desires has thus become historically impossible. They grasp social reality only through the internalized schemas of the system of domination itself. The possibility of qualitative political experience has been reduced to a minimum. Given their specific position in the institutional system, revolutionary consciousness groups can produce a certain level of clarifying counter-signals through sensuously explicit action [sinnlich manifeste Aktion]. In doing so, they use a method of political struggle that fundamentally distinguishes them from the traditional forms of political confrontation.

The agitation in actions, the sensuous experience of organized individual fighters in confrontation with the executive power of the state, constitutes the mobilizing factor in the broadening of radical opposition, and tends to facilitate a process through which proactive minorities become conscious within the passive and suffering masses. Through visibly lawless [irreguläre] deeds, the abstract violence of the system is transformed into a sensuous certainty for all. The "propaganda of the shot" (Che) in the Third World must be completed by the "propaganda of the deed" in the metropolises, which makes an urbanization of rural guerrilla activity historically possible. The urban guerrillero is the organizer of absolute lawlessness [Irregularität] as the destruction of the system of repressive institutions.

The university forms his security zone, more precisely, his social base, in which and from which he organizes the struggle against the institutions, the struggle over the dining hall and the struggle over state power.

What does all this have to do with the SDS? We know very well that there are many comrades in the student union who are no longer willing to accept abstract socialism, which has nothing to do with their own lives, as a political stance. The personal preconditions for a different organizational form of cooperation in the SDS groups are present. If integration and cynicism are not to be the next step, the refusal to comply in one’s own institutional milieu requires a guerrilla mentality.

The previous structure of the SDS was oriented toward the revisionist model of bourgeois member parties. The executive board bureaucratically gathered the paying members among itself, who had to make a mere abstract commitment to the goals of the organization. SDS, however, has not been able to fully assume the perfect administrative function of revisionist member parties because it is only a partially bureaucratized association, an organizational hybrid. In contrast, the problem of organization today poses itself as a problem of revolutionary existence.

Translated by Jacob Blumenfeld

Notes

1. Rudi Dutschke and Hans-Jürgen Krahl, "Organisationsreferat," in Wolfgang Kraushaar (ed.), Frankfurter Schule und Studentenbewegung. Von der Flaschenpost zum Molotowcocktail 1946–1995, Vol. 2, Roger & Bernhard, 1998, 287-290. The manuscript of the speech is lost. The printed text is based on a tape transcript. Some short unintelligible passages have been omitted. The Janossy quotes are from his book Das Ende der Wirtschaftswunder [The End of the Economic Miracle], which was only available in manuscript form at the time.↰

2. Coalition of SPD and CDU/CSU; killing of student Benno Ohnesorg by police at a demonstration.↰

3. A phrase coined by Dutschke and his comrades to describe a proposal in which small affinity groups of anti-authoritarians come together to do theory and praxis together. See Rudi Dutschke, “Zum Verhältnis von Organisation und Emanzipationsbewegung — Zum Besuch Herbert Marcuses,” in Kraushaar (ed.), Von der Flaschenpost zum Molotowcocktail, 259: “The organizational turn of the critical-liberating study would be the emergence of many small — six to ten people — anti-authoritarian ‘institute associations,’ in which, through solidarity-based cooperation, scientific education would be improved, common fields of research and work would be established, through ‘mutual aid’ (Kropotkin) a more non-dominating communication could be established. [...] On the basis of such a real solidarity between the different groups of society and the anti-authoritarian camp of the students, the question of the politicization of the factories would also be easier to imagine."↰

4. “Integral statism or state socialism is the most consistent form of the authoritarian state, which has freed itself from any dependence on private capital.” Max Horkheimer, The Authoritarian State, 1940. Online here.↰

5. A reference to the attempts at rapprochement with the German Democratic Republic, which came to a conclusion with the treaties with the East under Brandt in 1970-73.↰