Remaining Ungovernable

Mauvaise Troupe

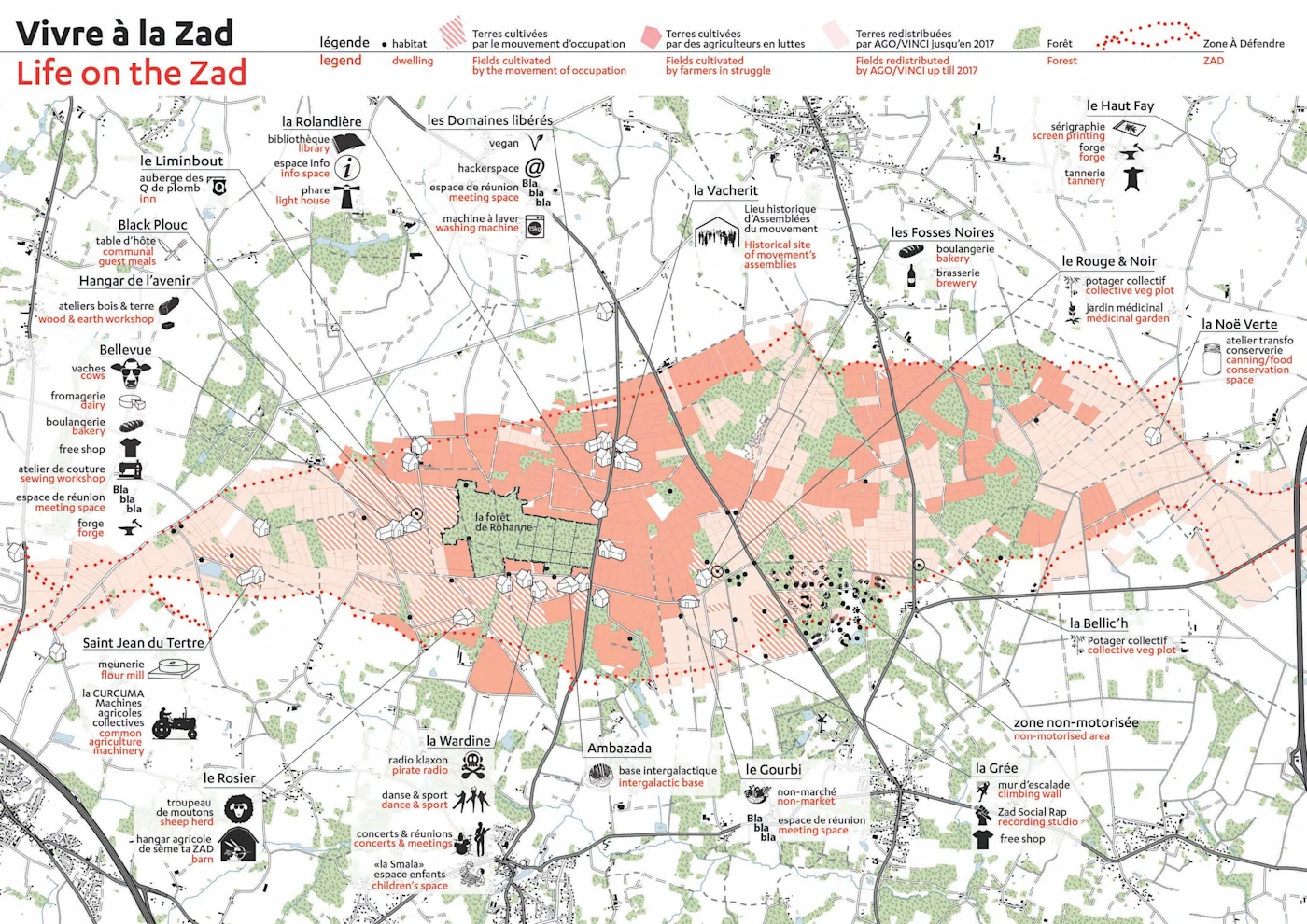

On January 17, 2018, Prime Minister Édouard Philippe announced on live television that the construction of the Grand Ouest airport at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, near Nantes, France, had been abandoned. The announcement marked the end of a 40 year struggle, the last segment of which had seen the emergence of a new political form in France encapsulated in the term “ZAD.” The term ZAD, or "zone to be defended" refers, first of all, to the occupation—by a few squatters in 2007, and then by several hundred people spread over dozens of living areas—of a 4000 acre territory as a form of resistance against its destruction. But ZAD has since become a commonly-used term to refer to any struggle to defend a territory.

For years, the ZAD was a focal point for those who aspired to a radical transformation of the world. It quickly became apparent that defending these wetlands was inseparable from inhabiting, nourishing, and building forms of resistant infrastructure within and upon them, and that all of these efforts were at odds with the existing economic and governmental structures.

In contrast to other Western European squats and temporary liberated zones, the ZAD crossed a threshold in terms of its duration, geographic scale, the number of people involved, the degree of rupture with mainstream society and the ambitious scale of material and political autonomy within its perimeters. The idea of a "free commune" was able to be deployed there. The ZAD also became a rare example of political victory in the last few decades in France: a victory against a major national project defended by every successive administration in power, which was won thanks to a new force and power dynamic established by the struggle against the infrastructure builders.

For years before the airport’s cancellation, the ZAD — renamed the "lawless zone” by our enemies — was a symbol of secession, and therefore a form of absolute scandal in the eyes of the republican state. This destituent process has a founding moment. The possibility of a free space introducing a real upheaval in the instituted frameworks often originates in an event that severs the mood of political fatality. In our case, this occurred during “Operation Caesar” in October and November 2012, when over a thousand state cops were mobilized to evacuate the area in which the airport was supposed to be built. Encountering fierce resistance from a countryside guerrilla as well as demonstrations of over 40,000 people who gathered to build an entire hamlet in a single day, the state mission failed. On November 24th, 2012, after hours of simultaneous confrontations in Nantes and in the Rohanne forest at the heart of the ZAD, the state announced the end of the operation. At once, the feeling of inevitability and powerlessness that comes with facing down backhoe loaders and gendarmerie squadrons evaporated from the hearts and minds of tens of thousands of people across the country. However, without a doubt the most complex challenge still remained ahead: to deliver on the full promise of this dazzling moment.

From then on, what we could refer to as our “destituent potential” translated into an ability to render the most visible forms of governmentality, in a given territory, more and more inoperative. For months after Operation Caesar, while it was already pretty obvious that the government no longer held the land, they continued issuing decrees and prohibitions on building, sowing, and bringing in equipment. In spite of police roadblocks and vehicle searches, the movement worked to defy these bans one after another. A convoy of tractors transported a barn in kit form over 300 km into the bocage 1. Construction sites were organized by having thousands of people enter the zone, circumventing the police roadblocks. Collective crop sowing actions took place on the fields slated to be airport runways, and a lighthouse was built where the control tower should have gone. At any given moment, each new decree issued by the state would contribute, in a de facto way, to the process of its own destitution, becoming yet another demonstration of its powerlessness. (One of the stronger symbols indicating that one was entering a territory no longer governed by the laws of the Republic were the roads strewn with barricades and cabins built directly upon the asphalt.)

For years, elected politicians in parliament would complain weekly about the highly visible existence of an area where the state, its laws, police and representatives could no longer enter. They would demand immediate action, which successive prime ministers would continue to promise, only to then postpone once again. One of the most audacious dimensions of this “destituent” process was the reaction to the June 2016 referendum over the fate of the airport project. After having pressed in vain upon various other levers — lawsuits, expropriations, threats, a vilification campaign in the media — the government tried to subdue us with its seemingly most legitimate weapon: democracy, the choice given to the people by referendum. Plenty of public commentary was made on the biased nature of the vote, its scope, and of the disproportionate means of electoral communication. On the evening of the vote, all the TV cameras and newspapers of the country were gathered near the barn where hundreds of people from the movement gathered. After the announcement of the victory of those that wanted to build the airport in the referendum, the journalists expected to see rows of sad faces, filled with renunciations and divisions. On the contrary, everyone began singing loudly that there would never be an airport and a huge party went on deep into the night.

I will not go into detail here on what has enabled the movement to carry on, nor on some of the tensions around the different strategies it used. It is nevertheless necessary to mention our relationship to “time.” For six years, we had to maintain the initiative, to always remain one step ahead, while also organizing sufficiently massive and threatening mobilizations any time the state discovered a window of opportunity and threatened to make a new attack on the ZAD. Additionally, the necessity of acting as if we were going to stay forever, even though everything was constantly threatening to collapse, contributes to a paradoxical relationship to time. In the years leading up to the state’s abandonment of the airport project, our apparently contradictory wager consisted in trying to reconcile the long term time scale of a forest, the consolidation of relationships and customs, growing crops or building solid durable constructions, all while facing a permanent sense of urgency. One cannot understand the ZAD without also evoking the idea of ‘composition’, which refers to the possibility of holding various extremely heterogeneous histories and political cultures together in struggle in a complementary and non-hegemonic way, e.g. peasant farmers and naturalists, NGO’s and squatters, builders and intellectuals. Making the arrangement function requires a constant attention to the possible transformation and evolution of each component of the composition, and a willingness to let go of the predetermined roles and subjectivities that the State requires in order to maintain its governmental narratives (citizens vs. radicals, violent vs. non-violent, etc.).

Let us return to the question of “destitution.” The practical experience of the ZAD and other similar autonomous spaces suggests that anything like a “pure” destitution is, in my opinion, a philosophical abstraction. First, because in the absence of a generalized insurrection, one continues, even in an autonomous zone, to interact with and partially depend on the state and economic superstructures for good or bad. Whether it is social services and social security, manufactured goods or certain energy networks and other external infrastructure. At a deeper level, the fact is that no community can exist or constitute itself without giving itself some structure of its own, frameworks and autonomous commitments without which it would be nothing but a pure sum of individualities, isolated gangs and liberalism — the opposite of a desirable community and movement. There is always the need to reinstate something. The key point is that what is instituted otherwise must be sturdy and dense enough that it does not inevitably fall back into the forms of governmentality and the exercise of power that we’re trying to get rid of.

What was it that supplied a positive texture to our "destituent" community? Perhaps it was our focus on developing customs and practices, rather than a legislative apparatus or an established charter. Perhaps it was our capacity, as exciting as it was exhausting, to question and debate at various scales — living spaces, activity groups, bigger assemblies — all the issues that concerned us. Perhaps it was our insistent refusal to separate those who make decision on matters from those who take charge of these decisions or must live with their consequences. In all things, it is a question of giving substance to our community through the songs, rituals, and collective gestures that engage us. For example, through the incredibly subversive and structuring power of that day of action during which forty thousand people came to the ZAD carrying batons that they drove into a bank of soil, while pledging to return, retrieve them, and wield them in defense of the zone in the event of attempted eviction. Shortly afterwards, the government gave up its threats of eviction again for some time.

One of the aspects that has quite logically been a central theme surrounding the experiment of the ZAD concerns the possibility of living without the police and courts. This was among the most complex challenges to overcome.

Until it was abandoned, the state took every chance it could get to ensure that the free zone and its community of struggle would collapse by itself. The state needed the ZAD to become unlivable, to serve as an off-putting and repulsive example of the ‘impossibility’ of living without its institutions, rather than a visible demonstration that life without them could actually be much better. Any space freed from the police unquestionably creates a desirable opening of possibilities, but it also tends to attract forms of life and practices that can abuse and endanger the community: drug dealing, the bloody settling of scores, a whole panoply of violence and abuse, all of which just as easily be found in any other part of the countryside or in cities. Too much collective inconsistency at this level can quickly be fatal to any free zone. This is an enormous challenge in a space that is keen to remain open and which wants to include a vast diversity of people having no pre-existing community tradition nor common ethical benchmarks. Similar problems became extremely acute in certain parts of the United States during the 2020 George Floyd insurgency, an uprising that warmed our hearts from thousands of miles away. For our part, we managed for some time to establish rotating conflict mediation groups that had a high level of involvement by inhabitants of the zone. A strong attention to bonds, and importance of debate and discussion at various levels always also plays an important role, but it did not prevent failures and tensions from breaking out in a violent manner at certain moments. However, the implosion of the ZAD so eagerly awaited by the state never occurred during the entire phase prior to the abandonment of the airport project.

On January 17, 2018, after 40 years of plans and 6 years of relative powerlessness in the face of the lawless zone and the popular movement around it, the government announced that there would be no airport. This was an enormous humiliation for them. But if it was not able to build the airport nor evict us, the State — taking a big step backwards — hoped to at least get rid of the ZAD. It needed to flex its muscles and to show the world that it had regained its toehold in the zone. Although we had been preparing for this moment for years and had worked to establish enough common ground between us to secure a future for the ZAD beyond the airport project, it wasn’t enough.

When the airport was finally abandoned, the possibility of maintaining a free commune and a "destituant" force was completely reshuffled. For many of us, it became a question of escaping the historical fatality of the “temporary autonomous zone” and the free insurgent commune, from its most illustrious manifestations such as the Paris Commune to more recent attempts. The free commune is condemned to a brief lifespan, beyond which it is either fatally reintegrated or else destroyed. The exception, perhaps, might be if it existed in hiding, which greatly reduces the possibilities for offensive and contagious action, and which in any case was not an option for us. Aside from the inspiring yet singular experience of the Zapatistas, carried out in a much larger territory, very few recent histories tell us anything else.

A large part of our political hypothesis was therefore bound up with breaking the spell of this ‘inevitability’, with its share of gooey romanticism and its self-imprisonment in the "history of the losers."

After the abandonment, initial attempts at negotiations between the movement and the state were quickly blocked. The demands of each side were far too opposed. A new operation of expulsion appeared inevitable. The state's revenge would be carried out with unmitigated debauchery, resulting in the largest internal military operation ever seen upon French metropolitan territory — until the Yellow Vests, in any case. On April 9th and the following days, we saw the arrival of thousands of police officers, tanks, drones, and a continuous bombardment of flashbangs, teargas, and shrapnel grenades wounding countless numbers of people and destroying many of the zone’s living spaces. After a few days of fighting, growing reactions beyond the ZAD, and a ceasefire with an ultimatum, each side was forced to reassess the balance of power.

We had become well acquainted with the destructive capacity wielded by the State, which threatened our bases of life. For its part, the State was also well aware that it was going to be very costly and politically dangerous to destroy us entirely.

It was also clear to us that we were no longer in a broadening insurrectional moment, and that we could not expect to save the ZAD once again by relying on a purely military balance of power. In the midst of difficult internal tensions and disagreements concerning the preferred strategy to take up, a large segment of the movement adopted an approach that combined a continuation of hostilities with a re-opening of negotiations, seeing this as preferable to the total destruction of this territory to which we had irremediably linked our lives. The State wanted us to accept certain legal frameworks in order to be able to say to the world (and to itself) that it was no longer a zone of pure secession, and that it had regained a toehold on the territory. We decided that we would nevertheless maintain a margin of self-organization, autonomy, opacity, and illegality in which the experiment of the ZAD could continue to unfold and to serve as a base of support for other struggles. Even though we are now no longer living under the threat of the total destruction of our fields and houses, and are faced by a much lower degree of urgency, this wager has meant a perpetual struggle since the abandonment, one which continues to today. It cannot be otherwise, as long as the free zone challenges the superstructures of the state and the market.

The movement’s farming capacity now covers some 400 hectares, almost twice as much as before the airport abandonment, and these fields are protected by 9-year rural leases. About 40 collective living spaces are permanently inhabited by somewhere around 200 people, many of which include not only houses but also structures designed for artisanal production and political, cultural, and social organization. In addition to the permanent residents, hundreds more pass through and spend time on the ZAD over the course of the year, and new generations of inhabitants settle and build homes here all the time.

Compared to the period before the abandonment, the essay "Considerations on Victory (and its Consequences)" developed a tension on this point: on the one hand, there is the intrinsically precarious and liberal dynamic of the “temporary autonomous zone” in the sense given to this term by Hakim Bey, which emphasizes the maximum deployment of the possible. On the other hand, there is all that is required to maintain a "free commune" (or at least a "commons") in the long term, since the development of lasting counter-spaces requires, once again, a certain formalization of frameworks, rotating delegations and a variety of commitments that structure the community. It is on this point, too, that we can modestly find ourselves in agreement with our Zapatista comrades: contrary to the idea of a purely destituent force, we see a need for singular and sustainable autonomous institutions in which power circulates and does not become fixed.

After the abandonment as before, the possibility of destitution and autonomy on the ZAD never resolves itself into a neat binary between a pure submission to the law and an illegalism that would necessarily be critiqued (by radicals) if it was anything other than total.

On the one hand, there are the frameworks by which the State seeks to regain its toehold in the area, and which sometimes also serve us as leverage points. This is the case, for example, with long-term rural leases that we have ended up signing on the land. On the other hand, there is everything for which we still have no ‘legal’ framework, everything that remains off the radar of the state. There is all that the legal frameworks officially state, and all the ways they can be hacked or rendered useless in practice. There are leases signed by ‘official’ individual peasants that cover lands that are shared in common and remain an active part of the movement. And there are all of the ethical frameworks, pacts and pledges made by those who use the land, which concern the many ways they give themselves to it and one another, which overlap and directly contradict those of the state.

Legal frameworks notwithstanding, it’s clear not only to us but also to the institutions of the state that, three years after the abandonment of the airport, the ZAD still remains tendentially ungovernable. In any case, it is at least partially ungovernable on a set of issues that appear to us as essential.

This became particularly evident when the COVID-19 lockdown set in, which was and still is extremely constraining and isolating in France. At a time when the rest of the country was in paralysis and only communicating through screens, the rules imposed at the national level were incompatible with the collective intertwining of the different places where we live, work and create on the ZAD. In the face of the virus, we were able to decide on our own framework for prevention. But we could also maintain our ability to meet in large assemblies, to travel, to party sometimes, to organize gatherings in the zone and to initiate a series of collective actions "against the re-intoxication of the world," and even to plan new land occupations outside of the ZAD.

As I write this, the 4th campaign of illegal logging in the Rohanne forest for the needs of construction and heating of the ZAD is about to begin. We still consider this forest and hundreds of other hectares in the ZAD as a "commons" that the traditional state institutions — which own it — are incapable of taking proper care of, and which it is up to us to care for. We are still squatting our homes and are preparing to illegally rebuild others for the third anniversary of the abandonment, including a historic farm that had been evicted and razed to the ground during the two waves of evictions.

At this level, the game has not changed all that much: it’s a matter of sustaining movement, developing ways to leverage power against the state, widening circles of support and forms of collective opacity that transcend any written official agreements.

Beyond the ZAD itself, a series of other victories were won against toxic projects for highways, tourist complexes, and mega-malls. Unfortunately, few were able to sustain zones of autonomy in the defended areas. However, in these times of dramatically increased awareness concerning the scale of the ecological disaster confronting us, it seems to us that planners will find it increasingly difficult to carry out the destruction of fertile land, forests, and wetlands, since they continue to encounter powerful forms of resistance that inhabits and defends them.

Not long after the abandonment of the airport, the Yellow Vests overturned all the reigning ideas concerning how to launch an offensive and overflowing popular movement. They carried us all the way to the threshold where a toppling of the reigning powers became a real possibility, but could go no further, perhaps for lack of a durable imagination of what might happen next. Now as before, the central problem lies in imagining together with others how we can amplify, here and now, the constitution of free communes easily joinable by others and organically linked to the construction of an insurrectional movement.

First delivered as a talk in November of 2020 during the conference on “The Undercommons and Destituent Power—Between Pandemic and the Uprising.” A video transcript and slideshow is online here.

Notes

1. Bocage: the French name for a particular checkerboard style of hedgerows, treelines, wetlands, forest and farmland of which the ZAD consists.↰