Short of the World, Short of Self

A.K. Parris

How do we present to ourselves the many catastrophes through which we are living? By positioning catastrophe in the future, as events that are still to come, do we avoid looking at the wreckage of our present? In what follows, philosopher A.K. Parris looks to Samuel Beckett's late play Catastrophe for a critique of our disastrous political and ethical paradigms. Rescuing Beckett’s play from its vulgar moralization at the hands of liberal humanists, Parris argues that its true intention is not to make a pompous display of solidarity with the dehumanized, the oppressed, and the victimized, but to dramatize the catastrophic performance of politics itself. In this way, Catastrophe enacts the political from the perspective of its own obsolescence. It invites us to have done with comforting tales of salvation, yet to remain unreconciled with the world even after the protagonist leaves the stage for good.

Part of our series Worlds Apart, exploring cosmology, ecology, science fiction, and the many ends of capitalist society.

In his 1962 article “Why Still Philosophy?” Theodor Adorno remarks, “it is completely uncertain whether philosophy, as a conceptual activity of the interpretive mind, is still the order of the day, whether it has fallen behind what it should conceptualize — the state of the world rushing toward catastrophe. It appears to be too late for contemplation.”1 To this we might add — if emancipatory politics is our project — it is completely uncertain whether philosophy ever was the order of the day.

Originally written for radio and subsequently published in the collection entitled Interventions, the concrete existence of Adorno’s article indicates that he believes philosophy was and still is the order of the day. I share in this Adornian affirmation of philosophy and want to suggest that one of our exigent philosophical tasks is to elucidate the time of catastrophes.

When not a mere synonym for disaster, catastrophe refers to the end of the world. Most philosophical and non-philosophical accounts of catastrophe therefore formulate it as singular and futural. Even Adorno’s remark points to such temporality insofar as he formulates catastrophe as that “toward” which we are “rushing.”2 But what are we missing in the reduction of catastrophe to an event to come? What worlds do we forsake or foreclose? It seems to me that by framing things in this way we actually perpetuate the very world whose end we’re attempting to think. If we want to orient ourselves toward an intervention in the present, then I propose that we must think catastrophe in the plural and in multiple temporalities other than the future. There is not one but many catastrophes, and they aren’t all waiting for us down the road; some have been with us a long time, others don’t belong to chronological time at all.

I’ve written elsewhere about the catastrophic past, the irreparability of the worlds that have ended but continue to condition our present.3 In the present piece I want to begin to think of catastrophe outside of time, in terms of eternity. Even Adorno, whose negative dialectics are rigorously temporal and historical, begrudgingly admits the power of eternity in philosophical thought. As he notes, “those philosophers whose doctrines insist on the eternal” find their “historical status” in critique, which has constituted the liberatory power of philosophy “from time immemorial.”4 But Adorno’s use of “eternity” here is a bad eternity akin to Hegel’s bad infinity, i.e., eternity as unending duration. Instead, I propose that we think of the eternity of catastrophes in Althusserian terms. Althusser (in)famously claims eternity is “not transcendent to all temporal history, but omnipresent, transhistorical, and therefore immutable in form throughout history.”5 In its transhistoricality eternity has its own liberatory power in history: it enables us to think the turn that returns us to catastrophes and to disrupt the reproduction of a world, which, as Adorno and Horkheimer observe, “is radiant with triumphant calamity.”6 What follows, then, are notes towards an investigation of the form of catastrophe.

Samuel Beckett's late play Catastrophe offers a useful starting point for such an investigation. As Adorno observes, “Beckett’s once-and-for-all is…infinite catastrophe." For much of his corpus “the end of the world is discounted, as if it were a matter of course.”7 In the words of Endgame’s Clov, "the earth is extinguished, though I never saw it lit. [...] All is in a word…corpsed.”8 What is performed in Beckett’s work is an ethos of the end of the world, or, more accurately, the ends of worlds, whose central question is: how does one go on, when one cannot go on? Beckett's literary and dramatic methodology depends, as Adorno notes, upon a “universal annihilation of the world,” one that “does not leave out the temporality of existence…but rather removes from existence what time, the historical reality, attempts to quash in the present.”9 Put differently, as Alain Badiou, the great thinker of eternity in our time, has argued, Beckett’s literary method could be characterized as one of ascesis: it reduces characters to their generic function in history in precisely the sense Althusser proposed when speaking of eternity.10 In his methodus aeternitatis, Beckett positions us to take a stand against the omnipresent “corpsed” condition of life today, or, as Adorno would demand, to “withstand the horror,” in neither hope nor despair for the future.11

This annihilatory or ascetic method is visible from the first page of the play Catastrophe, where Beckett’s character descriptions for each of the play’s four characters (Director (D), His female assistant (A), Protagonist (P), and Luke, the lighting technician (L)) are “age and physique unimportant.” With these methodological considerations out of the way — and hopefully without muddling “aesthetic semblance and reality” or disastrously suturing philosophy to its conditions, either political or artistic — we can now turn to Beckett’s play itself.12

Catastrophe, like much of Beckett’s late dramatic work, is short, numbering just under five pages. Here is the version created for the Beckett on Film project, which runs just over five minutes:

If we want to think catastrophe sub species aeternitatis through Beckett’s short dramatic piece, the question we must ask is the following: When D claims, “Good. There’s our catastrophe. In the bag.”...just what is the “there”? Although it derives from the Greek κατά (down) and στρέϕειν (to turn), I suggest we dismiss those who interpret the play as Beckett’s attempt to return the word “catastrophe” to its primary Greek and dramatically technical sense of “the change…which produces the conclusion of a dramatic piece.”13 Instead, I will borrow a now obsolete secondary definition of “catastrophe” as “the posteriors” and call bollocks (a proximate anatomical term that in his bawdy, bodily humor Beckett would no doubt appreciate) on the arses who foreclose our ability to think the form of catastrophe.14

Primarily, though, I want to call bollocks on the all-too-common liberal appropriation of the play, which interprets it as Beckett’s bold declaration of the individual’s capacity for resistance to oppression. This interpretation is emboldened by the historical circumstances of the concrete existence of the play, which was penned in 1982 at the request of the International Association for the Defense of Artists (AIDA).15 It premiered together with a number of other plays at Avignon Theater Festival that year in solidarity with the poet, playwright, and political dissident Vaclav Havel, who, at the time, had already been imprisoned by the Czech state for political subversion for more than three years. Indeed, Beckett dedicates the play — something he only rarely did — to Havel. Critics at the time saw in the play a “timely” and “radical shift in vision,”16 a turn from the so-called political impasse of Waiting for Godot’s “Nothing to be done” and the Trilogy’s “go on” to a politics of, as another commentator puts it, “man’s irreducible spirit, the triumph of the individual’s will.”17 Yet another commentator complains that Beckett’s political turn came “too late,” lamenting, “the play opens up a new political direction in [Beckett’s] work which time [namely, his death a few years later] did not permit him to take further.”18 Even today, after so much time, commentators take P’s act to be a symbol of “maintaining basic moral principles in the face of oppression,” as if what were in question was an individual asserting their “own dignity (and by extension, human dignity) without violence.”19

The reception of Catastrophe points toward the form of catastrophe itself. Against the interpretive consensus on salvific dignity, I think we need to frame the play in terms of its structural relations as a whole — without (I hope) submitting to the “craze for explication! Every i dotted to death!”20 There is in fact a dramatic turn in Beckett’s work in Catastrophe, but it is not what the dominant reception would have us believe; it is rather that the play takes place in a particular worldly location: the theater.

Most of Beckett’s plays take place nowhere in particular: in a room or desert, on a country road, street corner, or scorched grass, or, as is more often the case, literally nowhere, insofar as there are no preliminary stage directions emplacing the characters, just faint, diffuse light, gray light, or darkness. In their generic function, Beckett’s plays could be anywhere. The theater as the location for the theatrical production of Catastrophe suggests that all catastrophes are a human production. While most scientists now acknowledge the anthropogenic nature of the climate catastrophe, what I have in mind here is something stronger, namely, that all catastrophe is a form of social relation. Indeed, I want to read the metatheatricality of the play as an apocalypse21 of catastrophe: the play as play is the revelation that catastrophe consists in the staging of social relations we call politics — the spectacle of oppression and pseudo-resistance — a staging which itself perpetuates catastrophes. Catastrophe, then, is not Beckett’s belated turn to politics, but a commentary on the so-called politics of his — and, as I hope we will see, our — day. While it might be easy to dismiss the liberal appropriation, the following formal analysis also enables us to see certain parallels with radical political tendencies.

Let us investigate the staging of politics in the play. The dominant reception reads the play dyadically, as a relation of two characters: D and P. 22 According to one common and commonsensical reading, this relationship symbolizes “the objectification of the Other by institutionalized power.”23 The so-called catastrophe consists in D’s domination of P, his coercive fashioning of P as a passive, impotent body. Instead of fists — “He musn’t,” declares D. — P’s hands are “limp.”24 D demands that A “hide the face” and “down the head.”25 When A suggests, “[Timidly.] What if he were to…were to…raise his head…an instant…show his face…just an instant,” D responds, “For God’s sake? What next? Raise his head? Where do you think we are? In Patagonia? Raise his head? For God’s sake! [Pause.]”26 It is immediately after the refusal of P’s face that D declares the catastrophe to be “In the bag.”27 The narrative arc of the dominant reception, then, is a morality tale of resistance to the victimizing dyad: at the end of the play P no longer “submits, inert,” but triumphantly raises his head in dissent.28 In showing his face, P (re)asserts his humanity against repressive Power.

But if we want to think catastrophe sub species aeternitatis, this dyad is the wrong reduction. In the play there are four characters, not two. The other two named characters, A and L, perform the complexity of catastrophic social relations — actors both human and a-human, seen and unseen (or “offstage,” as Beckett’s character description has it). Indeed, D cannot do what he does without A and L; perhaps more to the point, he doesn’t do anything.

When commentators do analyze A, they see her as a sympathetic character sympathetic to P, analogously subject to the dictates of D: she follows or makes notes of his orders; most of her own suggestions are, according to the character directions, delivered “Timidly”; she even points out — though, not timidly this time — that P is shivering. But if “assistant” in name, she is the primary agent, the protagonist, if you will, of the action to which P is subject: A exposes P and proposes gagging him; she dictates, in both senses of the term, and legitimates P’s condition; her suggestion that P raise his head is conditioned by “just an instant;” she, according to the stage directions, “Transmits in technical terms,” D’s directions to L. In the proliferation of characters, there is a dissipation of the image of centralized Power; it is emptied out, dispersed. The multiplication of characters multiplies fronts. This multiplication pushes against the fixation on sites of Power, which fix the fight and limit what should be its generic openness. Such fixation often leaves politics caught in the wrong battle, under the illusion there is one — or a primary — front.

L is as absent from the reception of the play as he is from the stage. This silence on his character, as is so often the case with silence, says a lot. In the dispersal of characters power is de-personified. Power is not D — or Husák, or Trump, or any other of a list of proper names identified with power. There is also an impersonalization: in not seeing the character of L, we see that power not only is not one person, but also that it is not always human. As the technician, L operates the machinery of catastrophic social relations. In his absence he embodies the anonymity of the apparatuses of power, the institutions in which name is fungible with function. Or maybe, thinking with Günther Anders, he is that machinery, the figure of the co-mechanization of the capitalist global machine: “the triumph of technology,” Anders writes, “has led to our world — though it was invented and built by we ourselves — reaching such an enormous magnitude that it has ceased to be really ‘ours’ in any psychologically verifiable sense. It has led to our world becoming ‘too much’ for us.”29 L disembodied “offstage,” then, would be the embodiment of that “infernal rule” of disproportionality between our capacity to act and our capacity to conceive, perceive, and feel the catastrophic effects of the capitalist global machine — the Promethean gap that is not peculiar to but is arguably accelerated and scaled through the technology of the present.

But, one might ask, isn’t this “complexity” just the same old dyad? Aren’t these other characters reducible to the primary antagonism between P and D, in which D is the Director of the oppressive action and P is the oppressed object (until, of course, as morality dictates, he becomes a subject, the face of resistance)? Couldn’t we take A and L, to think with Anders again, as “sons of Eichmann,” in their “docile obedience to orders handed down,” their “painstaking compliance — unconscious compliance even — with the instructions given by the machine”?30 Aren’t these two other characters just two among the “millions of passive Eichmanns” in the primary relation between the Two who constitute the form of the One catastrophic social relation of oppression?31

Such a dyadic reduction does not account for the audience, the “them” of the final lines of the play: “D: Now…let ’em have it… Terrific! He’ll have them on their feet. I can hear it from here.”32 It is the staging before an audience that constitutes the metatheatricality of the play: all the named characters only perform their function for and before the unnamed character of the audience. In the written version of Catastrophe the catastrophe is different from the filmic version: the play does not end in applause from A, carrying into the credit sequence; rather, Beckett’s final stage directions read:

[Pause. Distant storm of applause. Protagonist raises his head, fixes the audience. The applause falters, dies.

Long pause.

Fade-out of light on face.]33

In this way, the structure of the play anticipates its reception, not only the applause of the audience internal to the dialogue, but by those watching its performance. In the stage directions we see that P raises his read in response to the audience’s applause, acknowledging that he is the product of their fantasy of catastrophe; his face is summoned by their ovation. He is their Protagonist, not D’s. “Distant,” the audience watches without witness in the reproduction of the conditions of catastrophe, driven by this illusion of Power as the Director of action and the consequent figuration of resistance, a subject turning from “crippled” hands to raised head. Like the applause itself, this figuration of politics is condemned to falter and die except in the reproduction of that which it claims to resist. It is this desire for a Protagonist, the spectacle of a victim or martyr and the performance of impotent rituals of pseudo-resistance, that Beckett’s play reveals to be the real catastrophe. It is audiences — like those at the Avignon Theater Festival that year, performing and applauding themselves for (indirect) action in (illusory) defense of oppressed artists or those today in viral hope or nostalgic ecstasy — whose P’s gaze fixes.

In its metatheatricality, then, the play provides a critical perspective on what Adorno calls the problem of art — and we can add the problem of politics — that “mimics reconciliation,” that is, art that reflects the reality it sustains in service of “that semblance and conformity the world demands.”34 For Adorno, we must confront the damaged reality that damages the subject, not by applauding some false image of resistance, but by undoing this image of the subject. In his dialogue with the art critic Duthuit, Beckett makes a similar distinction between what we can call reconciliatory art, art that is complacent and complicit in the perpetuation of the world, and unreconciled art, art that does not “turn tail” before being without the world:

All have turned wisely tail, before the ultimate penury, back to the mere misery where destitute virtuous mothers may steal stale bread for their starving brats. There is more than a difference of degree between being short, short of the world, short of self, and being without these esteemed commodities.35

Beckett’s art asks us to remain unreconciled even when we have no Protagonist.

In my investigation sub species aeternitatis, I’ve tried to show that Beckett’s play Catastrophe is not his overdue image of virtuous political dissent, but a criticism of the spectacle of the politico-moral fantasy of “mere misery.” It is a performance of the form of the catastrophe we perform in our politics. Instead of heeding the humanist cant, which plays at solidarity with the dehumanized, the oppressed, the victimized, we should recall The Unnamable’s can’t: “And man, the lectures they gave me on man, before they even began trying to assimilate me to him!”36 While someone like Anders wrote against the obsolescence of the human, Beckett’s work already occupies that place — and asks us to join him. Instead of turning tail and staying on the same course, which, in a variation on Benjamin, consists in the “catastrophe[s], which [keep] piling wreckage upon wreckage,” Beckett’s work unfailingly fails better.37 Only in turning toward the a-subjective rigor of “a fugitive ‘I’…the non-pronounial,”38 only in the fade-out of light on the face, self, and world, can we make the exigent political strophe or turn, which he describes as “turning from [the plane of the feasible] in disgust, weary of its puny exploits, weary of pretending to be able, of being able, of doing a little better the same old thing, of going a little further along a dreary road.”39

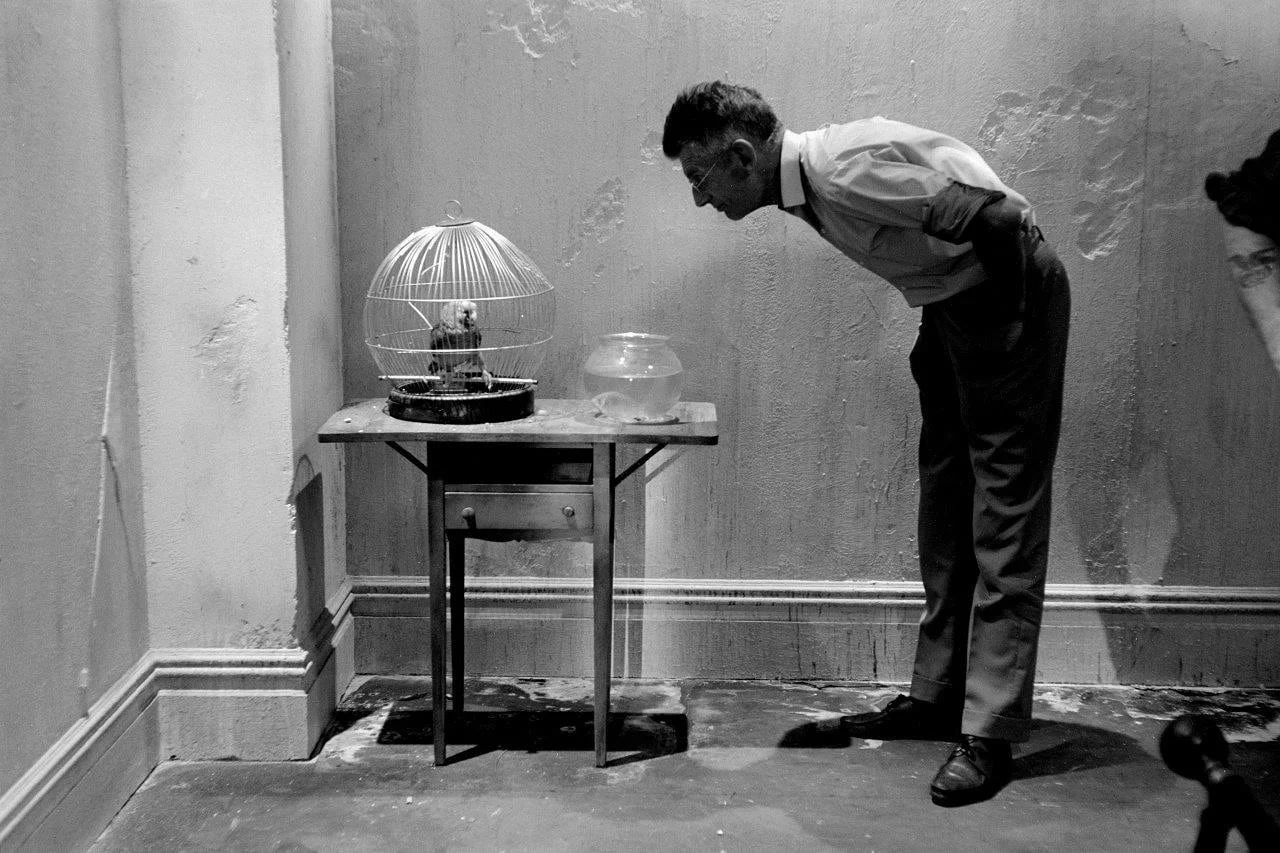

Images: Richard Avedon, Steve Schapiro

Notes

1. Theodor W. Adorno, “Why Still Philosophy?” in Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords, trans. Henry W. Pickford, Columbia University Press, 1998, 13.↰

2. The term “rushing” highlights another dimension of the temporality of catastrophes, namely, their quickness or slowness. On this question see Deborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, The Ends of the World, Translated by Rodrigo Nunes, Polity Press, 2017.↰

3. See my “The End(s) of the American West: The Time of Apocalypse in the Work of Cormac McCarthy,” in Philosophy in the American West: A Geography of Thought, eds. Josh Hayes, Gerard Kuperus, Brian Treanor, Routledge, 2020. I argue that in order for an untimely historical materialism to be capable of confronting the horror of our past and present, we also need a melancholy science by which to bear witness to the irreparable past as irreparable.↰

4. Adorno, “Why Still Philosophy?,” 8, 6, 10.↰

5. Louis Althusser, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards an Investigation),” in Lenin and Philosophy, Monthly Review Press, 1971, 161. ↰

6. Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments, Stanford University, Press, 1987, 1. ↰

7. Theodor W. Adorno, “Trying to Understand Endgame” (1961), in New German Critique No. 26, Spring-Summer 1982, 123. ↰

8. Samuel Beckett, Endgame, Grove Press, 1958, 29.↰

9. Adorno, “Trying to Understand Endgame,” 121, 124. ↰

10. See Alain Badiou, “The Writing of the Generic,” in On Beckett, Clinamen, 2003, 1-36.↰

11. Theodor W. Adorno, “The Meaning of Working Through the Past” in Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords, 100.↰

12. Adorno, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis” in Critical Models, 275. Such suturing is a constant theme for Badiou. In particular, see Alain Badiou, Conditions, trans. Stephen Corcoran, Continuum, 2009. ↰

13. “Catastrophe,” in the Oxford English Dictionary. ↰

14. In their work, both Adorno and Badiou rightly call bollocks on the existentialist appropriation of Beckett’s work. Adorno, for his part, tries to avoid the individualist existentialist reading, arguing that “Beckett’s dramaturgy abandons [individualism] like an obsolete bunker…[It] insinuates that the individual’s claim of autonomy and of being has become incredible” (Adorno, “Trying to Understand Endgame,” 126, 127). While Badiou, perhaps trying to rescue individualism as subjective truth procedure (he himself admits he is a Sartrean at heart), seeks to overcome the nihilistic existentialist reading, i.e., “the caricature of a Beckett meditating upon death and finitude, the dereliction of sick bodies, the waiting in vain for the divine and the derision of any enterprise directed towards others. A Beckett convinced that beyond the obstinacy of words there is nothing but darkness and void” (Badiou, “Tireless Desire” in Badiou on Beckett, 40).↰

15. For more on AIDA, the historical context of Une nuit pour Václav Havel at the Avignon Theatre Festival, and Beckett’s involvement in various political campaigns for artists from the 1970s onward,see the Conclusion of Emilie Morin, Beckett’s Political Imagination, Cambridge University Press, 2017. ↰

16. Bert O. States, Catastrophe: Beckett's Laboratory / Theater. Modern Drama Volume 30, Number 1, Spring 1987, 14.↰

17. Samuel Beckett, The Unnamable, Faber & Faber, 134; Lamont, Rosette, “New Beckett Plays: A Darkly Brilliant Evening,” in Other Stages, Thursday 16 June 1983, 3. To be clear, even Badiou thinks of these earlier works as an “impasse.” See Badiou, “Tireless Desire,” in On Beckett, 39. ↰

18. Kier Elam, “Catastrophic Mistakes: Beckett, Havel, The End”, Samuel Beckett Today/Aujourd’hui 3, 1994, 7.↰

19. José Francisco Fernández, “A Politically Committed Kind of Silence. Ireland in Samuel Beckett’s Catastrophe.” Studi irlandesi. A Journal of Irish Studies, n. 7, 2017, 165-184. ↰

20. Samuel Beckett, Catastrophe in The Collected Shorter Plays, Grove Press, 1984, 299. ↰

21. The word “apocalypse” is derived from the Greek for “uncover” or “reveal.” ↰

22. We should not be surprised, then, that even those critical of the liberal reading tend toward this dyadic reading. See, for example, Jim Hansen, “Samuel Beckett's "Catastrophe" and the Theater of Pure Means” in Contemporary Literature, Winter, 2008, Vol. 49, No. 4, Contemporary Literature and the State (Winter, 2008). Hansen offers a powerful critique of the liberal-humanist interpretation that reduces resistance to sympathetic identification with the oppressed. Yet even though he acknowledges that it is the audience that “makes the theater possible,” his Agambenian analysis is primarily of the relation between D (as sovereign) and P (as bare life), only secondarily in relation to the audience. ↰

23. Elam, “Catastrophic Mistakes,” 9.↰

24. Beckett, Catastrophe, 298.↰

25. Beckett, Catastrophe, 297, 299. ↰

26. Beckett, Catastrophe, 300. ↰

27. Beckett, Catastrophe, 300. ↰

28. Beckett, Catastrophe, 298.↰

29. Günther Anders, “We, Sons of Eichmann.” Translation by Jordan Levinson (1964). Online here.↰

30. Anders, “We, Sons of Eichmann.”↰

31. Anders, “We, Sons of Eichmann.”↰

32. Beckett, Catastrophe, 301. ↰

33. Beckett, Catastrophe, 301. ↰

34. Adorno, “Understanding Endgame,” 127. ↰

35. Samuel Beckett and Georges Duthuit, “Three Dialogues” in Samuel Beckett: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. Martin Eslin (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall Inc, 1965), 20. ↰

36. Beckett, The Unnamable, 36. ↰

37. Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” Translated by Edmund Jephcott, in Selected Writings Vol. 4, Belknap / Harvard University Press, 2003, 392. ↰

38. “My work has to do with a fugitive ‘I’ […] It’s an embarrassment of pronouns. I’m searching for the non-pronounial.” Lawrence Shainberg, “Exorcising Beckett”, The Paris Review, 29, Fall 1987, no. 104, 134.↰

39. Beckett and Duthuit, “Three Dialogues,” 17. ↰