Sketch of a Communist Political Doctrine

Junius Frey

The following is a Preface to the French edition of Chinese philosopher Yuk Hui’s The Question Concerning Technology in China: An Essay in Cosmotechnics, which appeared with Editions Divergences this year. In it, former Tiqqun member “Junius Frey” shows how Yuk reopens the question concerning technology through a radical appeal to our battered sense of inhabiting the world. Along the way, he juxtaposes Yuk's developed concept of cosmotechnics with the theory of Empire proposed two decades ago in Tiqqun’s Introduction to Civil War.

Other languages: Français, Español, Italiano In any case, the philosophers don’t interest me; I seek only wise men. -Alexandre Kojève, May 1968

The context

Let’s start by setting the scene. The historical (if not historial) scene. China has woken up. And as expected, the world trembles. In an alert sent to its trader clients, the forecasting unit of Deutsche Bank predicts a “cold war between the United States and China” in the coming decades, at the end of which “two semifrozen blocs will emerge” separated by a “tech wall” (The Age of Disorder, September 2020). The world, they claim, will be divided in two: on one side, there will be the framework inherited from globalization, and under American hegemony from every point of view — monetary and military, technological and cultural; on the other hand, there will be the “new silk routes” — the “belt and road initiative” — that extends from the definitive bringing-to-heel of Xinjiang to the purchase of Piraeus, or of certain jewels of Germany’s tech industry, from the mask diplomacy in Algeria to the installation of a Chinese military base at Djibouti, from supporting regimes threatened by street uprisings (Syria, Thailand, Myanmar) to an omnilateral politics of influence that has not overlooked South America, Africa, and the Middle East. Between the two sides, there will be strategies of containment and provocation, personnel poaching and all kinds of pressures, a thousand inconspicuous micro-battles and a gradual settling of allegiances country by country, party by party, company by company. Deng Xiaoping recommended “hiding capacities and waiting for our moment.” That moment has clearly arrived; it is even largely in the past. Witness the degree of intellectual development of the Chinese geopolitical vision: Jiang Shigong, official interpreter of “Xi Jinping thought,” commentator and exponent of Carl Schmitt’s work in China, and theorist of the annexation of Hong Kong, is not content to explain that “the world order has always functioned according to a logic of empire” (despite the parenthesis of the Westphalian order), or to interpret History as a story of a struggle between maritime empires and continental empires. Instead he observes, first of all, that the model of the present “World Empire 1.0” — how cruel a designation! — formed by Western Christian civilization and fully realized by the United States, faces three insoluble problems: “the endless growth of inequalities due to the liberal economy; the breakdown of States, political decline, and ineffective governance brought about by political liberalism; and the decadence and nihilism created by cultural liberalism.” He concludes his Empire and World Order (2020) in this way:

We are living in an age of chaos, conflict, and massive change, in which World Empire 1.0 is in decline and trending toward collapse, while we are as yet unable to imagine World Empire 2.0. […] Whichever civilization is able to provide genuine solutions to the three great problems facing World Empire 1.0 will also provide the blueprint for World Empire 2.0. As a great world power that must look beyond its own borders, China must reflect on her own future, for her important mission is not only to revive her traditional culture. China must also patiently absorb the skills and achievements of humanity as a whole, and especially those employed by Western civilization to construct its world empire. Only on this basis can we envision the reconstruction of Chinese civilization and the reconstruction of the world order as a mutually reinforcing whole.

There you have it: a statement that says what needs to be said, with few digressions.

Clearly though, as anyone who’s learned a minimum from our Chinese comrades about the reality of contemporary China is aware, the image of a pyramidal State perfectly unified through a Party whose tentacles extend from the neighborhood-level cell to its supreme advisory office, and where an absolute control of communications and a system of generalized technological surveillance paired with ruthless repression would finally manage to abolish the very idea of dissent, is nothing but a piece of propaganda. The success of this cliché is due to the opportune way in which it brings the Chinese state into agreement with its “liberal” detractors, both having an interest in exaggerating the state’s degree of perfection — either with a view to dissuading any rebellion by its citizens, or else to arousing a horrified disapproval. The reality of Chinese power is far more fragmented, far more cobbled together, far more deficient than all that. The relationship between bureaucratic verticality and “social” horizontality, between centrality and locality, is far more opaque, informal, and archaic than it appears. Technology malfunctions there the same way it does elsewhere, and the country’s inhabitants, though taken up in a process of modernization as heady as it is absurd, as powerful as it is anomic, though engaged in a total mobilization that has the means of its ambitions, are no more duped by the maneuvers of power than the typical European, nor any more heedless of environmental devastation and capitalist rapaciousness. Nothing is more precarious than the “Mandate of Heaven.” Which explains why nothing is defended more ferociously.

But what should matter to us, what is new in these past forty years, is the fact that, standing at the tail end of a dialectical confrontation between traditional Chinese and “Western” thought, a generation of Chinese thinkers has helped to fashion an imperial project for the world that goes far beyond “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” or the “fusion of Marxism with traditional Chinese culture” so dear to Jiang Shigong. The code name for this project is Tianxia, “all under the same Heaven.” Tianxia has become such a banality that China’s State Council Information Office can calmly proclaim, in a recent document, that “the Chinese system of development of international cooperation has its origins in the Chinese philosophy of the Great Harmony of ‘All under Heaven’ […] the traditional value that ‘everything under heaven is a great family and shares the same destiny.’” In 2017, the final section of the report of the XIXth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party already opened by stating that, “when the Way prevails, the world is shared by all” — an “ultimate ideal” that, according to the moderately enthusiastic commentary of Jiang Shigong, “encourages the entirety of the Party and the people of the whole nation.” There is a martial, Schmittian version of Tianxia, as well as a more honeyed, consensual, quasi-social democratic one (that of Zhao Tingyang, for example), and these two formulations are opposed like the two jaws of a pincer. The real merit of Zhao Tingyang lies in his carrying this imperial proposal through to its conclusion, while seasoning things smoothly. In opposition to a world history that would center itself around the European colonizer, he proposes as a regulative ideal for the contemporary world a model of Tianxia articulated around the ancient and mythical dynasty of the Zhou:

The perspective that informs the concept of Tianxia is based on the advent of a world system whose political subject would be the world itself, an order of coexistence whose political unit would be the world in its totality. […] Taking the world as the scale of measurement in order to interpret it as a global political existence is nothing other than the principle according to which ‘there is nothing beyond Tianxia’ […] The Tianxia system is only inclusive and not exclusive. It eliminates the very idea of strangers and enemies […] Every country or zone that has not yet adhered to the order of coexistence defining the Tianxia system will be invited to do so […] Tianxia is a world that combines the natural, the psycho-social, and the political spheres. The system of enfeoffment in the Tianxia of the Zhou dynasty established a ‘terrestrial network’ that linked the world territory into a reticulated system with a hierarchized structure […] Thus, even if hierarchy contravenes the values of equality, it remains nonetheless necessary to the good functioning of societies. The system of values has its rationality, and reality has its own. Concretely, as a ‘terrestrial network’, the Tianxia system of the Zhou possessed a suzerain kingdom that oversaw the world […] The suzerain State had the responsibility of maintaining the public order of the entire system […] China is a country that possesses in itself a structure of the Tianxia type, i.e., the idea of Tianxia realized in a single country […] The globalization created by the extreme development of modernity has drawn all men into an omnipresent and inextricable game […] it is a world that has failed. Globalization would appear to be the gravedigger engendered by modernity itself […] [It] is a disaster, certainly, but it also presents an opportunity for creating new rules of the game. […] Besides, God didn’t say that the Messiah is democracy. […] the histories of prophets belong to the prophets, and the histories of democracy to democracy. The true history of the world has not yet begun […] What will meet with an end is the modern era, not history.

It is not a question of knowing when the world’s scepter will effectively pass into the hands of China. What is important is to recognize that Chinese governmentality already serves as a model for the exercise of power in the West. It has already won. The only thing that conceals this fact from us is our ignorance regarding its reality as a mode of governmentality. It is obvious that all the world’s governments gaze longingly upon the freedom of maneuver enjoyed by the Chinese regime. Even the Defense Council by means of which Emmanuel Macron is so pleased to reign is merely a pale imitation of Xi Jinping’s National Defense Committee. Who are we imitating when we enter the entire population into security registries, when we simultaneously control social networks, expand police prerogatives, when the media is dissuaded from covering demonstrations that are described in any case as a pack of irresponsibles? Or when a crusade against “separatism” is launched? And is no one reminded of anything by the judicial condemnations for corruption that regularly sanction the loss of favor of this or that political clan? The very way in which the Western bureaucrat increasingly doubles as a capitalist is merely mimicking a thousand-year-old Chinese tradition. More fundamentally, what translates the symbolic hegemony of China is that what is spreading everywhere is an exercise of power based, in every domain, on the opaque and apparently neutral central decree of norms, rather than the citing of the Law. This empire of norms and the normal is expressed ethically by the now-universal habit among our contemporaries of evaluating, grading, and surveilling each other, a habit that renders the introduction of a centralized system such as the Sesame Social Credit System superfluous. The Coronapass and the constraints on the movement of bad citizens are obviously Chinese in this sense, as is the singling out of high-risk dividuals, and the ongoing replacement of the subject of law by the producing-and-consuming biological individual. The same is true of the secrecy that increasingly surrounds the exercise of real power at the summit of the corporations and the States, combined with the growing and increasingly “coproduced” transparency imposed upon “ordinary people” — in other words, the simultaneous proliferation of forbidden cities and snitches. The invisible structuring of the real by algorithms, combined with the making-visible of every act of daily life, derives from the most ancient Chinese theory of empire, as does the endo-policing it engenders. It is not only the haste to deploy 5G that comes from China, but also the project of a high-tech “ecological civilization” that serves to justify it, and the moralizing enrollment of citizens in that fiction. The epidemic that has propagated throughout the world from the industrial heart of the country has only revealed how Chinese governmentality already formed the universal paradigm. The total mobilization declared by Xi Jinping for the war against the “invisible enemy” found its ventriloquists in most of the world’s leaders. The insane experience of general confinement imposed on the Wuhan region — which was itself only a radicalized version of a mode of security-centered management of epidemics imagined by American anti-terrorism of the Dick Cheney era — has magnetized the global response to the epidemic. An entire system of organized distrust of each towards all, taking the mask as its symbol, imposed itself “spontaneously” everywhere, an entire ethos of resigned submission to the smallest extravagant norm that asserted itself as civic virtue under the pretext of “solidarity.” An entire naturalization of governmental intrusion insinuated itself day after day under the unassailable pretext of halting the spread of the virus. The idea that to govern is to follow the vagaries of Nature, and that power ideally merges with the order of things, already captivated Quesnay in the 18th century in his eulogy of China’s despotism. The fascination with Chinese politics during this whole episode went hand in hand with consternation over American politics. One can maintain, along with the Marxists of Chuang, that “the Chinese Communist Party functions as a vanguard for the global capitalist class” and that “its experiments are important precisely because they are situated on the first line of expansion of capital today, in both its industrial and financial dimensions, and are suited to the confrontation with the very limits of accumulation on its largest scales” (Chuang, Social Contagion).

For our part, we stand by what we wrote, twenty years ago, in the chapter of Introduction to Civil War dealing with Empire. Basing ourselves on the writings of a “legalist” of the third century B.C.E., Han Fei Zi, we submitted that “imperial domination, as we are starting to recognize, can be considered neo-Daoist” (Tiqqun 2). One knows that the first preserved essay by Mao Zedong, who was nineteen at the time, consisted of an apology for the cruel Shang Yang, the founder of “legalism,” and that Mao never let go of this fondness from his youth. And in fact, it’s hard not to see in the Cultural Revolution a scrupulous application of Shang Yang’s famous maxim: “It is always necessary to destroy what one has produced. […] To govern is to destroy: destroy the parasites, destroy one’s own forces, destroy the enemy.” It is all the more surprising to see Xi Jinping refer to legalism as regularly and as explicitly as he does, as in the “Document 9” of 2013 concerning “the situation in the ideological sphere,” and addressed by the Central Committee to the officers of the Chinese Communist Party. Therein Xi Jinping lists “the seven indisputables,” a modernized version of Han Fei Zi’s “five vermins.” He lists those flaws that harm the State by preventing the unification of thought, and around which debate is ruled out: “universal values, freedom of the press, civil society, civil rights, the historical errors of the CCP, crony capitalism inside the power structure, and judicial independence.” One can’t help but think that, for a moderately lucid mind, it was already evident in 2001, when Tiqqun 2 was published, that Empire was not so much American as it was Chinese. The course of things since then has done its utmost to confirm this suspicion — as it has almost every line in that chapter of Introduction to Civil War, moreover.

The Plot

Yuk Hui is an engineer and a thinker. Such a thing is rare enough that it deserves being mentioned. As a rule, one doesn’t expect an engineer to question the prevailing categories, or to remain true to his ingenium, to his own genius. Yuk reads Schelling in German as fluently as he programs in C++. He is as familiar with Heidegger as he is with the I Ching, with Greek philosophy as he is with the new Confucianism or the Kyoto School. There are few in this world who practice Aristotelian metaphysics with as much facility as they do Web ontology. In a period in which physical goods circulate as freely as metaphysics remain nailed to their natal soil, suited to little else than undergoing the corrosion of time, Yuk has produced a work, The Question Concerning Technology in China, that is without equivalent. A book that is not only a work of translation, meant for a Western public, but also a work of synthesis of the history of Chinese and Western thought intended for a Chinese public. For in China it is the very intelligibility of the past that a century of historic upheavals and confrontations with the West has compromised, by making it the material for successive, and successively opportune, reconstructions. “China dreams of its past, but it has become a country without a memory. […] The past seems close at hand, but it no longer speaks,” declares Jean-François Billeter in Chine trois fois muette. It would be a mistake to place Yuk’s work alongside the comparatist, pendular movement that has led so many Chinese intellectuals in the last decades to measure themselves against the Greek and German philosophical tradition in particular, mechanically concluding in favor of the superiority of the national tradition. Yuk doesn’t work for any party. While he does enter into the well-tempered exchanges of the academic sphere, his thought obeys the necessity of its own unfolding. He works, considerably and astutely, for us. The Question Concerning Technology in China should be read as an immense gift, which he alone could have crafted. At the cost of a slight anachronism, Yuk can be seen as the thinking avant-garde of a planetary generation whose ground fell out from under them with the announcement of the “Anthropocene” — to say it quickly, given how evident it is that the term created by Crutzen in 2000 to designate “a geological epoch dominated by humanity” remains congenitally stamped with the Prometheanism of which he simultaneously notes the disaster; but how could our obtuse modernity forgo the pleasure of celebrating its own funeral oration, and doing so in its own language? Yuk’s thought is thus inevitably planetary: one doesn’t get out of such a misstep, a catastrophe with such deep roots and such a universal reach, without a tremendous effort of synthesis from a historical as well as geographical point of view. Not only is it modest, but it makes us modest. In a few strokes it sketches out the complete theater of contemporary metaphysical operations. One has to see with what supreme gentleness he successively dismisses the flaccid constructivism of Latour, the wordy impotence of post-colonial deconstruction, the accelerationist gigantomachy and desperate postmodernism of Lyotard, the brilliant treatises with no object of Meillassoux, and the ontologizing of technology in Stiegler and Sloterdijk. For herein lies the problem of the philosophers: they need princes — as do the artists, it should be said.

The Question Concerning Technology in China is a book written for a generation of engineers dissatisfied with the destiny they’ve been promised, whom capital no longer manages to set to work without luring them with all sorts of traps repainted in green. For all the degree holders who desert their “bullshit jobs” by becoming bakers, mechanics, farmers or market gardeners, and suddenly feel themselves coming back to life. For those who can no longer entertain themselves with the aporetic jugglings of philosophy. For the new ascetics who realize that all the spiritual techniques of the universe will never be able to rebuild the smallest inhabitable world. For those who tell themselves that the encounter between traditional Chinese thought and the European tradition can be something more than a spiritual supplement for functionaries on the rise, à la François Jullien. The manic-depressive arrogance of Western man, defeated more than ever in his project of mastery, lost more than ever in his theodicy that is clearly turning into a nightmare, will perhaps find some measure of relief here. He will be consoled to learn from Yuk that a 5000-year-old civilization considers that the heart is the organ of the highest knowledge — intuitive knowledge — or that the resonance between being and the world can found the experience of truth (or indeed of heroic action), or that participation in what is greater than oneself does not have to take on the crutch of the social or that of mysticism. Given all this time that the Western subject has been searching for a remedy for his disorientation, Yuk comes at perhaps just the right moment. It’s not the least sign of the times that the latest offspring of German Critical Theory — Hartmut Rosa — no longer swears by anything but resonance. After a century of exploiting the category of alienation without drawing from it a positive perspective less sinister than the “full possession of oneself,” Critical Theory turns to digging in the Chinese tradition for its definition of happiness, indeed of communism — a bold move, it must be admitted. It calls to mind those atavistically mechanistic French doctors who, in desperation, send you to an acupuncturist “even if they don’t believe in it, but out of simple pragmatism, because it works” — as if their epistemology was not thereby found lacking, as if their science wasn’t fundamentally in crisis. Following the course of the discoveries in the neurosciences – lord, how badly the Ego, consciousness, and intentionality are doing! – or even simply in plant biology, it will be necessary to deploy an even more active denial for Western metaphysics to avoid being wrecked by the advances of its own investigations. Without a doubt, this civilization with its flat tires will need to multiply the oriental patches if it intends to keep on rolling. This seems to be its last hope. The pillage of material resources is thus succeeded by the pillage of spiritual resources. Luckily, there is no shortage of anthropologists specializing in “alternative ontologies” — and looking for work.

The “question of technology” is assuredly one of the most poorly framed questions of the twentieth century. In technology some believed they glimpsed the prosthetic complement necessary to a human species that is incomplete, maladapted, and precarious — peccaminous, to put it in the Augustinian language — or else the expression of the vital superabundance of that “animal of prey which is man” in his “struggle against Nature, which is hopeless, but will be endlessly pursued” (Spengler, Man and Technics). Others preferred to interpret the technical evolution as a gradual spiritualization of man tending toward the unification of the species into a “global brain,” even a union with God, or the gradual exteriorization of human faculties pushed to a point where it gives birth to the last man, a half-wit specter maintained by a “corps of master illusionists” wandering the surface of an earth become inhospitable (Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech). What is striking is that technology is always envisaged in terms of a supposed “human nature.” Even Heidegger, in his early reflections on techné, departs from the Greek definition of “what there is that is most troubling” (Introduction to Metaphysics). But as Marshall Sahlins has sufficiently taught us: if there is a Western illusion par excellence, it is clearly that of “human nature.” As a result, the same ones, such as Spengler, who claim the contrary, tend to think technology on the basis of the instrument, as if the latter constituted an ethically neutral operational mediation between the human subject and the world. For what characterizes the instrument is the polite distance that it keeps relative to the subject who wields it, its way of remaining inessential, vestimentary, to him, of leaving him intact. Instrumentum in Latin is the ornament, the piece of clothing, the furniture, possibly the armament. Now, the fact is, there is no instrument. There is no gesture, relation, or use that leaves the human unaltered. In order to be healthy, the relationship with oneself, the relationship with others, and the relationship with the world are one and the same thing. They form a “transductive” unity, as Simondon would say. It is precisely their disjunction that sickens, that alters us. In technical activity, the result does not at all erase the process. It is not the subject that makes use of the means, but the means that make use of the subject. The end pursued “thanks to the instrument” is still a means. The goal never overrides the immanence. The true efficacy of the act resides within itself, in its incident effects and not in its exterior effects. Everything is in the incident. Or to say this along with Simondon, “technical normativity is intrinsic and absolute.” (Individuation in Light of Notions of Form and Information). Once the “technical mediation” is isolated, one can very well do an autonomous and triumphal history of technical progress where everything is cumulative, where there is never a retrospective turn, or even a science like the “technology” of Leroi-Gourhan, patterned after biology, where “the technical elements succeed and organize themselves in the manner of living organisms” and where “in its continuity, human creation imitates universal creation” (Milieu et technique). Here one sees quite clearly how the “Omega point” of Père Teilhard de Chardin, toward which all of cosmic evolution is supposed to converge in Christ, is not so far away. Such “visions” inevitably end up lifting off towards Mars, the singularity, and the quest for immortality. They do not occur by chance in the moments when humans, confronted with the immensity of their ravages, begin to wonder whether they might be just “failed animals.” The years following the Second World War had their Teilhards, their Ducroqs, and their cyberneticians; our era has its [Yuval] Hararis, its Elon Musks, its Peter Thiels, and its Bill Gates. The last word in this matter belongs to Oppenheimer, who read the following lines from the Bhagavad Gita just after the Trinity nuclear test explosion, with tears in his eyes: “I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

The great merit of the notion of cosmotechnics as Yuk develops it is to break with the instrumental idea of technology, to bring technology back down to earth without losing the horizon of the world. Every technology is not only situated, appearing in and engendering a quite particular type of world, but it also determines a regime of subjectivation that is peculiar to it. Every technology is also a technology of the self — it is this that has typically been lost sight of in the transition from alchemy to chemistry, for example. Every technology is stamped with a singular mode of presence to the world, and constitutes a way of making it consist locally; it is at once cosmomorphic and ethopoïetic. In other words: it is understandable only in its relation with a form of life. Mauss had already tried, in his Techniques of the Body, to consider techniques independently of the fetishism of the tool and the machine by looking at the effects of American cinema on the gait of the women of his day, or the ways of swimming and running. When it comes down to it, nothing is closer to a theory of forms of life than Balzac’s theory of walking. To illustrate the thing, let’s take the very type of what was to represent “progress” in the twentieth century — the nearly simultaneous appearance in the years 1910-1920 of the modern bathroom, the standard bedroom, metropolitan architecture and urbanism, the mass automobile, Taylorized labor, advertising and the problems of sentimental optimization characteristic of the corresponding society. One can say that what matters here is the goal envisaged, the increased efficiency: a better hygiene, more family contentment, more light and space in the new lodgings, a greater mobility in every respect — in short: “progress,” the “maximization of possibilities,” as the lugubrious Ismaël Emelien would say. Or, one can instead focus on the ethical dimension of this massive technological evolution, on the texture of the “world” it configures. And then you will have Sinclair Lewis’s Babbitt for the American version, or the Babichev of Yury Olesha in the novel Envy for the Sovietic version. In the 1920s, moreover, one said “a babbitt” to name this new type of human. Anyone who’s read these two novels full of tenderness will hesitate a little to speak of “progress.” Just as there is no such thing as “Man,” there is no “Technology” in the sense given to the term by technophiles and technophobes alike. If, for more than a century, the critique of technology has pontificated in the void, this is because it calls out painfully to a “Humanity” that doesn’t exist.

Grasping the ethical dimension of each technology is precisely what the Chinese tradition, and the Daoist one in particular, can help us with, as it allows us to detect the intimate nature of beings beyond social coding, beyond the visible attributes, beyond the world of convention and of rhetoric, beyond intentionality and apparent action, even beyond language. “This way of coming up against the limits of language is ethical” wrote Wittgenstein to Schlick in a letter of December 1929, in which he attests to his sympathy for Heidegger. Every technology is an involuntary incorporation of the world; and perfect incorporation, perfect mastery implies, as we know, the disappearance of all will. This ethical understanding of technology, which is expressed so well in the two anecdotes from Zhuangzi cited by Yuk, that of the butcher and that of the hermit watering his garden, is also found in Adorno, who writes the following in Minima Moralia: “One cannot account for the newest human types without an understanding of the things in the environs which they continually encounter, all the way into their most secret innervations. What does it mean for the subject, that there are no window shutters anymore, which can be opened, but only frames to be brusquely shoved?” And in fact, the more the human subject imagines himself as sovereign, the less he perceives how he is affected by the technologies he utilizes, and the more he becomes the plaything of his own “instruments.” Instrumental reason is the ruse of ethical reason. To take an example as mundane as it is obvious: everyone knows what being at the wheel of a car can turn the most charming person into — on the subject of “automobile possession,” moreover, much could be said about the relationship between neoliberal governmentality — the conducting of conducts — and motorized propulsion: it is not certain that every individual could have been made into such a docile and malign pilot of their own existence without first having made them into a driver.

To sort through this extremely tangled question of “technology’ in the West, it may be that a judicious pairing of the celebrated genealogy of technology based on the “dephasing of the primitive magical unity” in Simondon –— so dear to Yuk — with the less celebrated genealogy of religion in Caillois as it appears in “Le grand Pontonnier” might be of some help. In his On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects, Simondon describes how the emergence of the technical object, which “is distinguished from the natural being in the sense that is does not form a part of the world,” comes to break the primitive magical unity where “man finds himself tied to a universe experienced as a milieu.” Simondon explains the birth of the technical object as the result of an alteration of the cosmic feeling of participation, and the advent of religion as a response to that alteration — religion being tasked with restoring the plenitude of that participation. He describes in this way the “dephasing” of the magical world as dividing into technology on the one hand, and religion on the other. Caillois, for his part, proposes a genealogy of religion based on the fact that the master of Roman religion is called “pontifex” — maker of bridges. He tells how one evening, in the course of a passionate discussion while walking Mauss back to his bus stop after class, how Mauss settled the age-old debate (as old as Lactantius or Cicero) on the subject of the etymology of religion. For Mauss it was obvious that the religiones were “knots of straw for stabilizing the beams between them.” The idea here is that the construction of a bridge — the very symbol of the technical object — does harm to the ordo rerum, the “disposition of the elements of the universe (and also of the institutions) as God conceived and established them.” “Building a bridge is a sacrilegious subterfuge which, as such, compromises the order of the world and cannot help but draw down a terrible punishment on its author, his family, his nation. The price for this has to be paid,” writes Caillois. That is what the pontifex does, by sacrificing to the Gods, by saying the right formulas, by proceeding to the appropriate rites, by arranging his religiones. He reestablishes the threatened equilibrium; he restores the transgressed ordo rerum. In a sense, he serves as a lightning rod against the wrath of the Gods. Caillois describes in this way, from a complementary angle, the compensatory decoupling of technology and religion theorized by Simondon. But what is important is that both interpret the birth of technology in terms of man’s cosmic participation in the universe — a participation that forms the basis of Chinese cosmotechnology as set out by Yuk. This genealogy sheds light in passing on the nature of contemporary technology, which wears itself out miserably multiplying the parodic versions of all the operations that one traditionally ascribes to magic — telepathy thus becomes the telephone; action at a distance becomes remote control; provoking the apparition of spirits becomes invasion of images and screens; out-of-body voyages become spatial expeditions; and the alchemical or Daoist search for immortality becomes a research project at Google’s Singularity Institute. Even Averroes’s “active intellect” has found its flawed materialization in the digital cloud. The technological prestidigitation aspires in this way to reconstitute the primitive magical unity between technology and religion by aping it grotesquely. It imagines bringing about a dialectical synthesis between technology and religion capable of healing the rupture caused by their dephasing, but actually only produces, by way of rediscovered plenitude, an autistic technicity, a cut-rate sacrality, and a general infantilization. The experimental technological utopia currently underway, that of a humanity confined to their homes, can be understood in this light: it proposes that we simply inhabit our own worldlessness [acosmie]. It aims to spare us the experience of the loss of the world by depriving us of the experience of it. Reducing the world to the house accomplishes the final domestication. Everything is configured for the new imperial citizen, tele-consuming and tele-living behind the screen of his smartphone or computer, experiencing himself as the supreme center of his world. Never has he been so free to command, to “navigate,” to inform himself, express himself, and never too has he been such a puppet of the algorithms of the organized powers. He must be a prisoner to be drowning in so many offers of escape! What is underway is a kidnapping of the world. Simondon entrusted the happy reunion between the technical universe and humans to what he too called a “technology,” but with an entirely different meaning. Negatively, this is what also makes it possible to consider the notion of cosmotechnics.

To speak of “cosmotechnics” is to speak of a pluralization of worlds, a centrality of the ethical element, an attention to the smallest gesture, a basic continuity between individual and universe, a heterogeneity of forms of life. It is to speak of the end of modernity as a human unification-totalization on the axis of abstract time, about the final passing of the great Western odyssey of progress, about the dismantling of technology as the metastatic assembling of the most profitable techniques into an operational global system, once they have been ripped from the worlds they came from. From a cosmotechnical point of view, there is a small problem with the West in general, and more particularly with modernity as it has spread its illness to the dimensions of the planet. Here we can follow Alfred Sohn-Rethel and George Thompson, when they attribute the birth in Greece of philosophical speculation, of a separate intellectuality, and, why not, of formalized geometry, to the autonomization of value brought about by the appearance of money in the framework of a society as mercantile as the ancient Athenian empire. In the European Middle Ages as well, there are ample proofs of the link between the development of the “mechanical arts” and precapitalist accumulation, whether this had to do with a Benedictine order aspiring in this way to “restore fallen man” (Didascalion, Hugues de Saint Victor) or with the cities of the nascent bourgeoisie. On the other hand, “there is no doubt that the failure of the merchant class to ascend to power, in the State, is at the very source of the failure of a modern science to appear in China,” declares Needham in La science chinoise et l’Occident. To speak of “cosmotechnics” is thus also to speak of an end to capitalism as a technological system and an end as well to the fable of modernity. Heidegger defines modern technology as a covering over, as a screen concealing the anarchic coming to presence of phenomena, the profusion of the multiple — “let us not look for anything behind phenomena: they are themselves the doctrine,” insisted Goethe. But it is modernity itself that proceeds by way of a covering over: as Jean-Baptiste Fressoz has shown in his Apocalypse joyeuse, it is not the case that there was a prior phase of technological innocence in modernity that came to an end upon the realization of its “limits,” i.e., the devastation it visited upon the environment and upon human interiorities. There was no point at which modernity, having become reflective, changed into “postmodernity.” In La fin du monde par la science, Eugène Huzar already foresaw, in 1855, that industrial activity could very well alter the earth’s climate; and Huzar was read and debated, extensively. Every offensive of modernization encountered resistances and criticisms, and crushed them. It then carefully erased the traces of its crimes, only preserving in its chronicle, in the chapter devoted to touching aberrations, the notion that those “romantics” had confined themselves to feeble protests. “The history of technology is the history of these power plays, and of the subsequent efforts to normalize them” (Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, Apocalypse joyeuse). During his 1912 deposition before Congress, Taylor assumes that the introduction of scientific management is part of a war against workers — a war conducted “for their own good,” obviously. Detlef Hartmann, the only German operaist theoretician of any consequence, has amply shown how technological progress should be understood: as a continuous, relentless offensive. Modernity has set upon everything in its path, bodies and souls. It was simply required to also produce the mechanisms of disinhibition that make the modernizing unconscious possible — and this continues today with the promise of a green capitalism. There is no need to “surpass modernity”: surpassing, as a methodical negation of the given, constitutes the very gesture of modernity, and “what has to be accepted, the given, is — so one could say — forms of life” (Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations).

Modernity is neither a period nor even a project of obliteration and dismemberment that would be realized in history like the work of an automaton. Modernity is a smoking battlefield, littered with corpses and worlds that have been dismembered, disfigured, broken, plundered, bulldozed, and finally museified — in Europe as in China. We mustn't be unjust towards the defeated, towards our dead, at least not if we hope one day to win. Because it is from them that our strength comes, it’s they who make us indestructible. We are not alone in the face of modernity. We are there, with the cohort of the defeated, with the entire army of our dead. Faced with the current offensive of green capitalism, which vows to take care of the bodies of the living as well as that of the planet the better to complete its work of devastation, we need not be afraid to reference the genuine desire for apocalypse that haunts our contemporaries. Toward the end of One-Way Street (1928), in a fragment titled “To the Planetarium,” Benjamin makes this very Yukian remark:

Nothing distinguishes the ancient from the modern man so much as the former’s absorption in a cosmic experience scarcely known to later periods. […] It is the dangerous error of modern men to regard this experience as unimportant and avoidable, and to consign it to the individual as the poetic rapture of starry nights. It is not; its hour strikes again and again, and then neither nations nor generations can escape it, as was made clear by the last war, which was an attempt at new and unprecedented commingling with the cosmic powers. […] But because the lust for profit of the ruling class sought satisfaction through it, technology betrayed man and turned the bridal bed into a bloodbath.

One thing is the announcement by the savants of the approaching extinction of humanity that everyone hears but no one listens to — how can you believe in the end of the world when the one announcing it, the scientist, is characterized precisely by the fact that he doesn’t have any world, but only a laboratory and colleagues, that he is the “pure individual” Simondon spoke of? One would have to be as absent from oneself as Bruno Latour to be able to say as he did in 1982: “Give me a laboratory and I will lift up the world!” Another is the diffuse desire for apocalypse that corresponds, among our contemporaries, to a terrible longing to renew a contact with the cosmos, to shed all the technological trappings that grip them, be it at the price of a catastrophe. Their deafness to the Gospel of the Anthropocene is not just an ethical inertia, a consumerist stupor, or a lack of survival instinct; it is also an irreversible paganism. One thinks of the fire pits and of the stars above the roundabouts occupied in the dead of winter by the Yellow Vests of 2018, of the Minneapolis precinct station in flames after the murder of George Floyd, of the sky over the burning barricades of the occupied polytechnical university of Hong Kong – there is something cosmic in every popular revolt of a certain magnitude; there is a world that ends and another that is reborn – there is apocalypse and regeneration.

The Denouement

In August 1945, Alexandre Kojève, KGB agent, high official assigned to the Ministry of Finance, self-proclaimed Gaullo-Stalinist, France’s negotiator at the GAAT agreements in Havana, inspirer of the French position in the framework of the Marshall Plan, future kingpin, if there ever was one, of the construction of the European Economic Community, drafted a “sketch of a doctrine of French politics” for the postwar years. This sketch has remained famous for its proposal of a “Latin Empire.” In that statement Kojève actually takes up the project of a “Latin Union,” formulated in that summer of 1945 by the Occitanist Resistance fighter Jean Cassou. But his proposal is so little the fruit of the prevailing circumstances that Kojève will continuously rework it up to 1949. The analysis of France’s position that he puts forward, which the passing decades have not contradicted, rests on the Schmittian assessment that “the nation states, still all-powerful in the nineteenth century, are ceasing to be political realities […] The modern state is not really a state unless it is an empire.” From this Kojève deduces the situation of France as being caught between two empires: on the one hand, the Anglo-American empire including Germany, founded on the Protestant cult of work and the economy, deploying a productivism of the individualist type, and on the other, the Slavic-Sovietic empire of Orthodox inspiration where the productivism is collectivist in nature. He sees no other survival for France, particularly in the face of the inexorable economic hegemony of Germany, than the building of a “Latin Empire”, grouping together Spain – at the modest price of overthrowing Franco –, Portugal, Italy, and France, a kind of empire of non-economy on a unity of mentality characterized by

...that art of leisure that is the source of art in general, by the talent for creating that ‘sweetness of living’ that has nothing to do with material comfort, by that very ‘dolce farniente’ that only degenerates into laziness if it doesn’t follow upon a productive and fecund labor [...] This common mentality, which involves a deep sense of the beauty that is generally associated (and more especially in France) with a very pronounced sense of right measure, and which in this way makes it possible to transform simple bourgeois well-being into an ‘aristocratic sweetness of living,’ as it were, and often to elevate to joy the pleasures which in another ambiance would be (and in most cases are) ‘vulgar’ pleasures […] for […] one has to admit that it is precisely to the organization and the ‘humanization’ of its leisure that future humanity will need to devote its efforts.

He goes so far as to note the spontaneously “municipal” character of the “Latin World’ and references the “Renaissance, which is probably the historical Latin period par excellence.”

If we analyze the historical situation with which we are confronted at present, there is no doubt that we are again caught in a configuration that resembles that of 1945. A new cold war for world hegemony has begun: the Anglo-American empire to which Germany remains subservient is at grips with the Chinese empire, whose “authoritarian” governmentality has basically gained the symbolic upper hand. The Latin countries, if not Europe in its entirety, have completely disengaged on the terrain where the battle is being fought: technology and economic power — to say nothing, obviously, about military power. They are now only good for exporting signs of distinction destined for the rest of the world’s privileged classes, be it protected-origin products, luxury items, expensive cars, or the production of a refined tourism that is exhausting the last local deposits of “authenticity.” It is this formidable historical demotion that has been revealed by the mimetism and arrogant impotence of Europe faced with the “COVID crisis.” Our fate, something akin to Italy during the Renaissance, is not only to be the spectators of History unfolding, but to become the powerless theater of the clash between foreign rapacities. Back then, Italy was a simple chessboard for the competition between France, Spain, the Germanic empire, and the papacy, Renaissance Italy finding itself in a situation where “from the outside one assumed for it the indispensable role of historical agent. It was more or less unburdened of that. This is why for Italy politics became an art. It was the first to apply its reflection to that. So Italy was relieved of the need to do politics […] so much so that one cannot help but give the Socialist ‘end of history’ the traits of Italian culture” (Dionys Mascolo, Le communisme). Withdrawing from the historical struggle, the Italian cities had thus transposed the struggle to the terrain of the beauty of life and the cities — this is what Dionys Mascolo calls “aesthetic socialism,” which is not by chance a communal socialism. The Renaissance, then, as the product of a desertion from the futile confrontation between the historical powers and as a brilliant revenge on them.

Put this way and transposed to the current context, the idea of a new form of “Latin empire” with its vital force not in the state apparatus but in the subsisting worlds and those still to be born — an empire that can very well make light of national borders seeing the quantities of tomatoes that are now consumed in Berlin — might resemble a program of renunciation coupled with a hope for revanchist consolation. Such is not the case. There is a strategic depth to this possible historical outcome, and one that makes Yuk a precious ally. As Jean-Michel Valantin has amply documented in L’aigle, le dragon et la crise planétaire, the Anthropocene is a “Sino-American battlefield.” Amazonia is already burning from the Chinese appetite for Brazilian transgenic soybeans. The melting of the Arctic constitutes a commercial blessing and a geostrategic bone of contention before being the cause of the rather regrettable slowing of the Gulf Stream. The pressure exerted by climate chaos on agricultural production is a variable in the clashes between military chiefs of staff. But contrary to the futurology of Valantin, which would have us believe that generalized artificial intelligence, the digital transition, smart farming, and agricultural drones could give rise to an “ecological civilization,” or even that in the end, instead of engaging in a suicidal rivalry, China and the United States will put aside their differences to save the planet, it is evident that the American and Chinese project of acceleration is headed for the wall. Its only reason for being lies in the fact that acceleration is the only way modern societies have to stabilize their senseless trajectory. Acceleration, like every international race for power, answers first of all to an internal calling. This is what the geopolitician is trained to not understand. No one believes in the purposes claimed: it is only a matter, for all that governs, of maintaining the status quo by the only means possible — the flight forward. No geoengineering project will intervene to slow down the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere. No multinational will ever manage to clean the moribund oceans as a way of glossing its image after the last industrial cataclysm it will have caused. If one day some world leader acts as if they are hearing Bruno Latour yelling fire, it will only be to gain a little time, and hence a little money. Bill Gates will not save Africa, nor a fortiori the planet. Gasoline will only make room for the “green energies” by adding to the oil spills the clearcutting of all the forests — excuse me, “biomass” — left in the world. The search for traces of extraterrestrial life will only come to a stop with the last traces of terrestrial life itself, with that quest having served to distract the gaze of survivors overcome by an incomprehensible anxiety. High-precision agriculture — that is, complete barbarism — will not forgo extending its empire for anything in the world, and it will be certified “organic” to boot, and if we are destroying in spades what is left of the Parisian North banlieues (à la Robert Doisneau), this is on the pretext of constructing eco-neighborhoods and High Quality Environmental (HQE) buildings — which in any case will remain desperately empty. The wind turbines, two hundred meters high, only expand and decorate the distributed monstrosity of an electric grid that will give up neither coal nor nuclear. Every technological scheme for remediating the ravages of capitalism only piles new insuperable contradictions atop the old ones. There is no reasonable soul in any prince of this world that we can petition for a slowdown or for resonance, no corporation that envisages converting from technological domination to cosmotechnics. The heavens are already so empty for the metropolitans that they are barely surprised to note the appearance of one of Elon Musk’s glaring satellites. To take the “subjective” side of things, we cannot help but agree with Lewis Mumford’s prophecy, which is now seventy years old:

Never before was man so free from nature’s restrictions; but never before was he more the victim of his own failure to develop, in any fullness, his own specifically human traits: to some degree, as I have already suggested, he has lost the secret of how to make himself human. The extreme state of post-historic rationalism will, we may confidently expect, carry to a further degree the paradox already visible: not merely that the more automatic the means of living become, the less life itself will be under human control, but the more rationalized become the processes of production, the more irrational will finally become the end product, man himself. In short, power and order, pushed to their final limit, lead to their self-destructive inversion: disorganization, violence, mental aberration, subjective chaos.

It is said that the compact power of the Chinese Communist Party is more capable of bringing about the necessary green swerve by its implacable means than any of the squishy liberal Western democracies. In China as elsewhere, all the serious and informed observers find themselves participating in media hype around voluntarist mirages that terminate in abortive failure. The acceleration that is underway aims solely to ensure a more complete mastery, and a more molecular control, of human masses ever more subject to panic before the effects of progress; it is only a matter of tightening the mesh of the net so as to contain the deserters inside it. It is a speed race that pits the approach of catastrophe against the increase of control. What does it matter which one wins: the train of technological civilization will roll on toward the abyss at a more and more terrifying rhythm. Just as there was no “overcoming of nihilism through nihilism,” there will be no victory of China over the West by means of Western technology. As Yuk makes so clear, China is itself overtaken by the means it has employed — it has in turn been the plaything of its own instruments and of an ontology as foreign as it is hostile. Contemporary Chinese films bear constant witness to this stupefaction, this existential befuddlement and this feeling of hopeless alienation. The Chinese as well, whatever the opportune revivals of Confucianism, Maoism, Daoism, or legalism, have lost the thread of their own tradition, through having trampled on it. The only thing characterizing the contemporary Chinese among all the Moderns is a more innocent ardor for general mobilization, a less weary craving for consumption, and a somewhat less deeply wounded, and hence somewhat more excitable national pride than that of the average American. What else but a global coronavirus could have emerged from an urban agglomeration peppered with party billboards proclaiming, “Every day, a new Wuhan!”?

If the current economic and technological course is headed straight for the wall, then it must be admitted that taking a step backward might mean taking several hits in advance. Deserting the always-already doomed game of the powers-that-be might inaugurate a new kind of game. Tearing oneself away from the historical struggle could be the only way to prevail over a confrontation that is itself a losing proposition. Let us leave “ChinaAmerica” to its sad fate; it will reverse itself soon enough upon the realization that we had gone ahead of it in the only feasible and favorable direction. Moreover, there is every indication that the most substantial reserves of invention, in almost every domain, do not reside in a greater orgy of means invested in the failing mechanistic paradigm of modernity, but in the disposition to escape from it and experiment with cosmotechnical hypotheses that have been regarded as eccentric up to now. This is where Yuk’s proposition is most meaningful, and deserves to be taken very seriously by the French reader. Perhaps it is incumbent on us, latecomers from a continent on which the sun never sets, to gather what the Daoist tradition has composed that is most vivifying, spiritual, and paradoxical. Perhaps it falls to us to re-attach ourselves anew to the earth and the sky in such a way that we cultivate an efficacy no longer centered in exterior effects, in what is produced [ce qui est produit], but in what takes place [ce qui se produit], i.e., in the ethical and not the intentional dimension. It could be that a form of healing as general as our amputation was civilizational announces itself there. It could be that those young agronomists who short circuit into communal farming instead of doing stints as consultants in aeroponics are like the birds who take precipitous flight and thus announce the approaching storm, or tsunami. It could be that the only future for engineers resides in the dismantling of the industrial system, just as the only future for the nuclear industry is the business of dismantling the nuclear power plants, or the “management” of Fukishimas to come. If there is a condition of “resilience” in the chaos that is announcing itself, it consists in pulling out of the great technical networks, whether they are for supplying electricity, communications, or food — in ceasing to depend on them. When even an entire continent would commit to the cosmotechnical way, the communal scale would be its privileged option. The deindustrialization of Europe is considered anathema only by virtue of the refusal to recognize it as the only viable path towards a reasonable future. Those who worry, like Frédéric Lordon, that in the event of a general secession they will have to give up not only their made-in-Shenzhen computer but also their plastic pens from India, simply lack the ability to think in a processual as opposed to a programmatic way. The technological unification of the world, which underpins the Empire and its ethical homogeneity, has reached its culminating point; whence the vertigo of anyone envisaging the possibility of a return to earth.

Simondon noted in his day that “modern man degrades technicity and sacrality at the same time, in the same way, and for the same reason”; he calls for saving the technical object from “its current status, which is miserable and unjust,” for saving it in particular from its commercial adulteration. For him, there is a plurality of technicities just as there is a plurality of sacralities. His thought is wild, brilliant, contradictory, exploratory. With its extreme sensitivity, its relational, organic, dynamic comprehension of phenomena, it is akin to that of Yuk. It calls for us to disconnect, to turn our gaze from the dubious goals that shimmer in the distance to the immanence of every technical reality. To restore the visibility of all those infrastructures that determine our way of living and are so fond of blending into the background. Wherever we may be, wherever we cast our eyes on the world that surrounds us, we find ourselves confronted with the aberrations imposed by economic logic — totalization, control, measurement, innovation, profit. The urgency to return to earth and disconnect from the insane course of civilization is basically the same as the one that requires us to contemplate Western metaphysics, notion after notion, and to blow apart the technological continuum, object after object. There is as much to be discovered in the genealogy of the technical objects that environ us as there is in the archeology of knowledge, as many barely begun bifurcations as there were of those doomed by “historical necessity.” And at work in both is essentially the same passion for understanding how a thing functions and to what altogether different use it might lend itself. The division between utility and beauty, between technology and ethics, between the “reign of necessity” and the “reign of freedom,” between an individual initiative and a collective need, loses any sense once one engages the process from someplace. Everyone senses that this is what the present demands. The wave of desertion swells as the impasse materializes. Here everything depends on our relation with time: “If we maintain a Puritan time-valuation, a commodity-valuation, then it is a question of how this time is put to use or how it is exploited by the leisure industries. But if the purposive notation of time-use becomes less compulsive, then men might have to relearn some of the arts of living lost in the industrial revolution: how to fill the interstices of their days with enriched, more leisurely personal relations” (E.P. Thompson, “Time, Work-discipline, and Industrial Capitalism”).

Translated by Robert Hurley

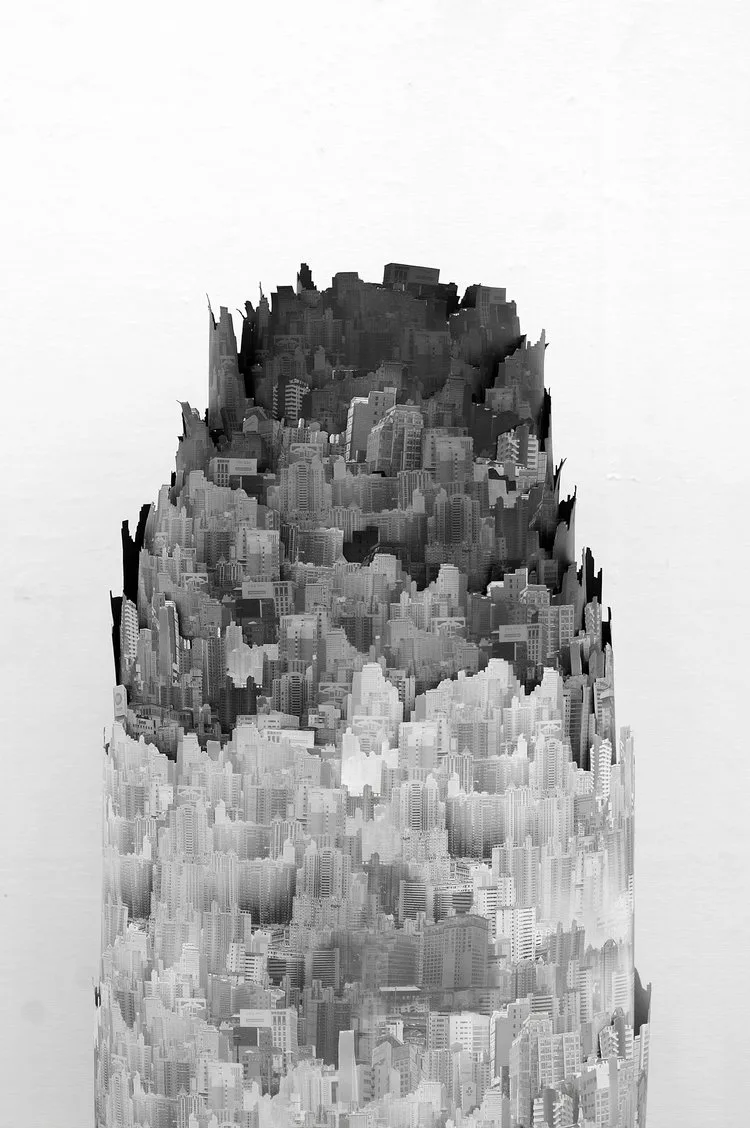

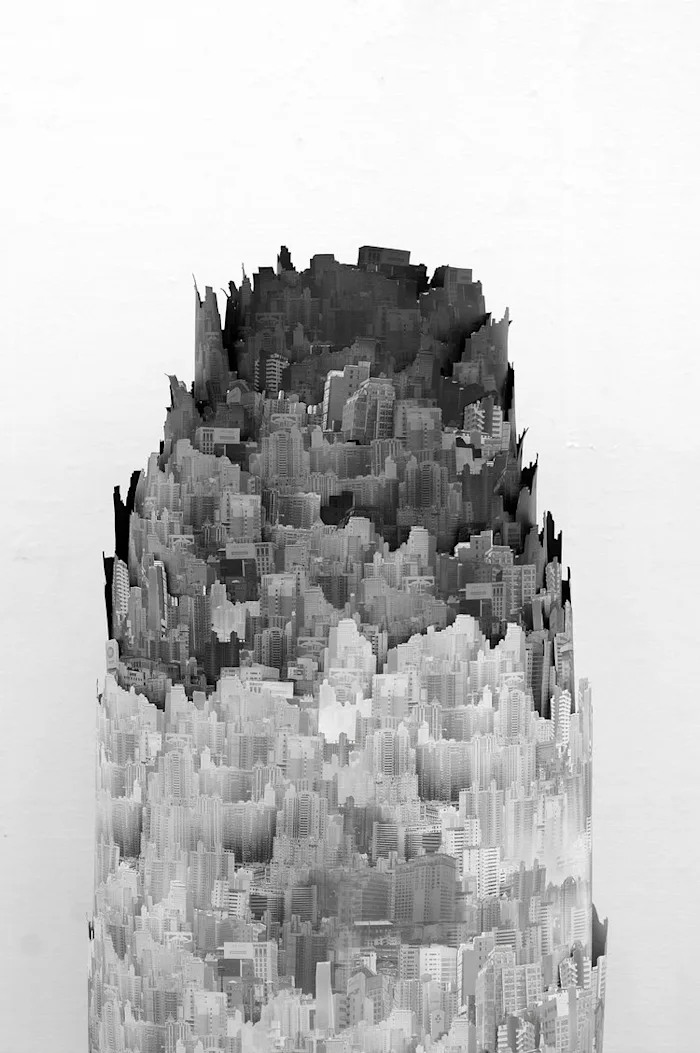

Images: Yang Yongliang