Strange Embrace: Paradoxes of Homosexual Desire in the Third Reich

Evgenia Skvortsova and Nikolai Kolya Nakhshunov

For this reason I consider that troops composed of boys of twenty, under experienced leadership, are the most formidable. —Ernst Jünger, Storm of Steel

Estimates suggest that between 5,000 and 15,000 queer people were sent to concentration camps in Nazi Germany.1 Tens of thousands more were convicted of homosexuality, imprisoned, and subjected to conversion therapy, castration, or execution. Since the 1960s, the pink triangle — which the Nazis forced homosexuals to wear in the camps — has become a primary symbol of the LGBTQI+ movement's struggle for equality and existence, and a form of remembrance for those who suffered discrimination and repression, especially in its inverted form, during both the early gay liberation movement as well as the global fight against HIV/AIDS that came later. Still, it is hard to believe that there were no more than a hundred thousand queer people among the Third Reich's population (of around 79.4 million in 1939). The present text aims to address those who were not deported and killed.

Another important symbol of queer liberation movements is the slogan, “We are everywhere,” which still appears on pride posters. Yet when we turn to history, this slogan becomes troubling. If we were truly everywhere, it means we were not only among the oppressed but also in positions of power: plotting, scheming, and committing violence. The podcast Bad Gays by writers Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller exemplifies this reality, illuminating the less-than-heroic traits of famous (and obscure) queer figures, including Nazis and their supporters.

According to Jack Halberstam, a leading figure in contemporary queer theory, “the purpose of any such investigation should not be to settle the question of homosexuality in the Nazi Party, but to raise questions about relations between sex and politics, the erotics of history and the ethics of complicity.”2 Adopting this approach, we ask: why did gay men participate in a regime that destroyed their own kind?

If we focus specifically on gay men, this is because their collaboration with Nazism presented a paradox: while Nazism exterminated gay people, it also glorified men and masculinity. Even among those with only a superficial knowledge of history, Nazism — also known as German fascism — is associated with male power.

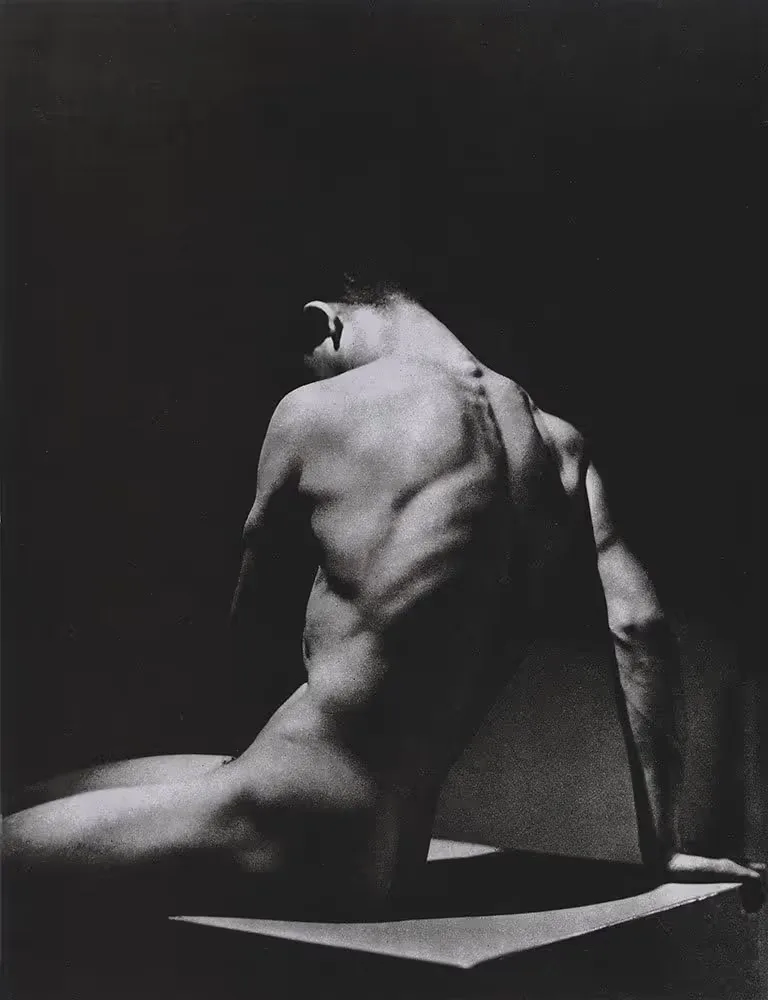

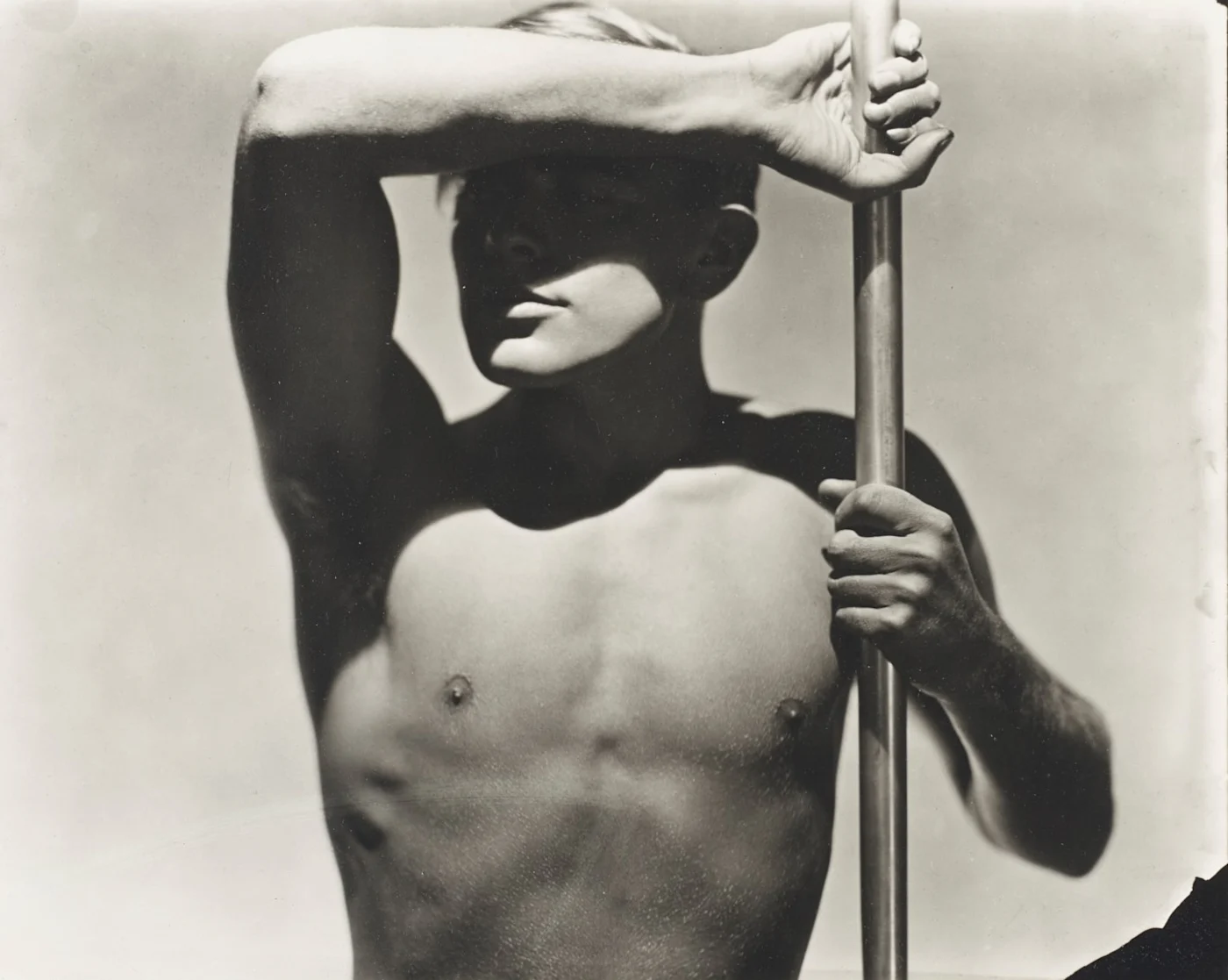

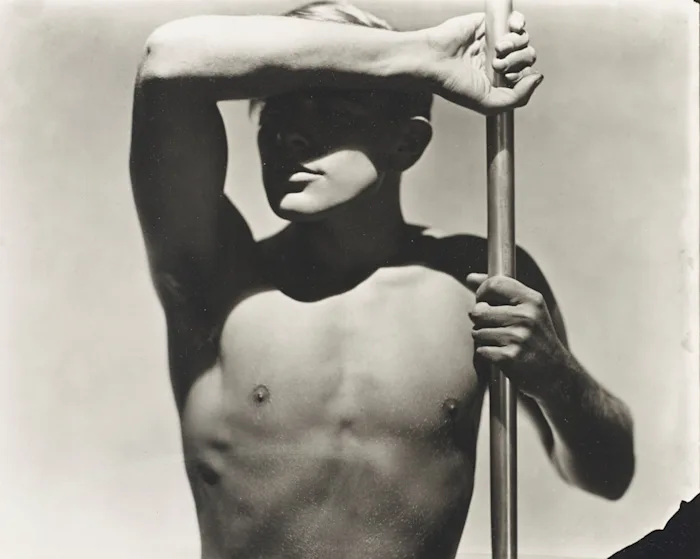

The Nazi soldier, the elite of a totalitarian society, embodies performative masculinity in a literal sense.3 His actions and image convey a specific cultural understanding of masculinity: machismo, militarism, heroism, and whiteness. He is both cruel and unapproachable, yet he can also evoke unbridled sexual desire — as if he has just stepped off the set of an erotic photo shoot or gay pornography film.4

Our aim is to trace how fascist culture both suppressed and appropriated homosexuality in order to forge identities through violence and the othering of difference. Contrary to the repressive hypothesis — which claims that power can only restrict — we argue that Nazi totalitarianism was not merely a regime of sexual repression, nor was it asexual. It was a regime of total control over sexuality. It purged all “dirty” and queer elements while striving to engineer a certain “idealistic” gender and sexual type in its laboratory. This regime still manifests itself nowadays in forms of homonormativity and homonationalism.5 For instance, contemporary LGB alliances, which deliberately exclude trans- and queer people and people of colour, bear subtle and overt traces of fascist ideology, which asserts sexual and gender superiority. This compels us to turn to history.

Gay men between camps and barracks

The history of sexual desire has never been homogeneous or linear. It has evolved through strange encounters, embraces, and exclusions that may seem unpleasant — or even disgusting — from today’s vantage. Michel Foucault’s work on the history of sexual normalization6 has shown how same-sex desire was appropriated by various regimes of power-knowledge, which both rendered it visible and codified it in medical and legal terms. Some sexualities were normalized, others pathologized, and others simply ignored. We’re less interested in how views of homosexuality developed, or the intellectual history of the concept itself, than how homosexual desire was or was not integrated into society, the role that desire played in forming or destroying social ties, and how it was both persecuted and glorified — of course, in secret.

The radical state homophobia that characterized Nazism began long before the Nazi movement existed. In 1871, when the German Empire was proclaimed, Paragraph 175 of its criminal code stipulated that “unnatural vice” (widernatürliche Unzucht) between two men was punishable by imprisonment or loss of civil rights. Obsessed with imperialist and militaristic ambitions, Emperor Wilhelm I and his chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, sought to extend the rules enforced in the Prussian army to all of society. They subjected even personal relationships to strict discipline — especially between men, who were universally regarded as potential soldiers and defenders of the fatherland.

However, as German imperial power declined, the state relaxed its regulation of homosexual relations. Although Paragraph 175 remained in effect during the Weimar Republic, Berlin became known as the capital of sexual freedom and scientific progress in sexuality research during the early 20th century. In 1897, German-Jewish doctor Magnus Hirschfeld and his colleagues established the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee — the world's first organization dedicated to protecting gay rights. He later founded the Institute for Sexual Science to study sexual variation. Dr. Hirschfeld devoted his life to decriminalizing and normalizing (while sometimes pathologizing) homosexuality, producing hundreds of scientific and activist works. For many contemporary LGBTQI+ activists, he rightly occupies a special place in the pantheon of queer movement activists.

However, the development of knowledge about sexuality also has a dark side, strangely intertwined with Nazism. Dr. Hirschfeld was a follower of the Enlightenment tradition, characterised by a penchant for experimentation, coercion, and totalitarian rationalism, and affinity for eugenics were no secret to his contemporaries. Once, he even justified medical sterilization for people with perceived intellectual disabilities.7 On the other side of the ideological spectrum, “Masculinists” cleaved to the opposite extreme and looked to the ideals of German Romanticism. They criticized Dr. Hirschfeld and his supporters for believing in a “third sex” as a distinct category of person, situated between male and female. Instead, the Masculinists advanced ideas about the superiority of homosexual men, their special bonding with one another, their misogyny, and sometimes antisemitism.8

Among the main voices of the movement was the magazine Der Eigene, founded in 1896 by Adolf Brand — a proponent of egoistic anarchism — which later became a community of the same name. Its supporters “thirst[ed] for a revival of Greek times and Hellenic standards of beauty, after centuries of Christian barbarism.”9 To them, “Greek times” represented an era not only of male domination, but also of flourishing pederastic culture, when older men could sexually exploit younger ones, and of the aesthetic ideal of the naked, athletically built white body.10 Entirely in keeping with the spirit of German national romanticism, this vision was overlaid by the idea of the “Männerbund,” which held that the “instinctive sympathy”11 between men was the foundation for heroism, patriotism, and homeland security — which men do closely together, back-to-back or in other positions. It is important to note that Masculinists neither invented the Männerbund nor gave it an erotic connotation; they merely revealed the strange intimacy that can develop between men in moments of crisis.

What crisis? The concept of the Männerbund — which embodied German popular resistance during the Napoleonic Wars — resonated powerfully with nationalist sentiments in early 20th century Germany. The empire led, then lost, World War I in a crushing defeat, plunging the country into economic and social collapse. Meanwhile, women gained rights to public participation, the “communist threat” loomed larger, and the carefree bourgeoisie indulged in amorous pleasures for all to see. Returning defeated from the battlefield to a country in economic decline, many soldiers found themselves traumatized. Familiar social hierarchies and markers of identity were losing their value. This existential and material fragility profoundly influenced younger generations as well. Though they hadn't experienced the brutalities of war firsthand, they could hardly envision a peaceful civilian future under such conditions. Frustrated by the empire's broken promise and unable to adapt to new realities, they yearned for predictability — for a time when man was master of the world, when his status was guaranteed by his gender alone. They longed for a fantasmatic system that had never actually existed. Thus, in search of reassurance, many men renounced their families and egalitarian relationships — including romantic ones — and joined hierarchical male brotherhoods that promised a non-contradictory worldview, protection by older comrades, and the restoration of former national glory. This is precisely what the Nazi Party, the NSDAP, ultimately becomes: “Machismo in uniform,” as the historian Richard Bessel put it.12

The history of the Institute for Sexual Science, founded by Hirschfeld and his colleagues, is telling. Founded to address the sexual issues facing German society and the emergence of new types of attachments and intimacies, the Institute was looted and destroyed on May 6, 1933 — just months after the Nazis seized power — by the German Student Union and the Stormtroopers (Sturmabteilung, or SA), the NSDAP’s main combat organization until 1934. Though the SA’s backbone consisted of First World War veterans, it also attracted many young men, many drawn to its elite status and the sense of community that it proffered. When accused of recruiting very young boys into combat units, the Nazi newspaper Völkischer Beobachter responded: “Exactly, and from these will grow those whom we do not have today, namely German men!”13

Yet, there might have been other forces at play in the decision of these fair-haired young men to join the NSDAP and unite with others who looked and thought just like themselves. The stormtroopers lived, slept, worked, sweated, and showered together. They surely were drawn to each other. The Christmas 1931 edition of the Hamburger Tageblatt published the following note:

We have lost everything, we have gained everything. We gave up father and mother and fiancée and friend, gave up money and goods and our blood. Some of these things we gave easily, some with more difficulty, but we have all gained one thing that no man or God can rob from us — we have gained our comrades.14

Yet these “sentimental” Nazis were also capable of rape and murder. Impulsive and coarse behavior, drunkenness, sudden outbursts of violence, intimidation of civilians, as well as crude and often fatal treatment of women were commonplace among them.15 These same men would later organize and participate in one of the bloodiest catastrophes in human history.

Masculine nationalism and sexual modernism converged in Ernst Röhm, chief of staff of the SA, resulting in a thorny mixture of homoeroticism and homophobia.16 Described as a “swashbuckling mercenary, father and drillmaster to his troops, straightforward and tactless,”17 Röhm embodied the cult of virile comradeship that defined early Nazi paramilitarism. His personal motto — “Only the real, the true, the masculine held its value”18 — captured his faith in a hypermasculine ethos that prized male strength, loyalty, and martial camaraderie. A close confidant of Adolf Hitler and reportedly the only man permitted to address the Führer informally, Röhm symbolized both the vigour and moral ambiguity of the Nazi revolutionary movement.

Röhm's homosexuality was an open secret within Nazi circles and a weapon for his political opponents. Despite the party's political homophobia and convinced conservatism of its members, Hitler initially defended Röhm, declaring that “private life cannot be an object of scrutiny unless it conflicts with basic principles of National Socialist ideology.”19 He characterized the SA — Röhm's “Spartan boys” — as “not an institute for the moral education of genteel young ladies, but a formation of seasoned fighters.”20 Within this aggressively masculine culture, homoerotic undertones were tolerated as long as they reinforced loyalty and soldierly unity. But this uneasy coexistence of homoeroticism and homophobia would soon unravel.

As Röhm's political influence grew, so did the SA's independence and its reputation for disorder. The stormtroopers' rowdy behavior and persistent rumors of homosexuality among its leadership threatened the Nazi Party's carefully cultivated image of moral purity. When Röhm's personal correspondence with physician Karl-Günther Heimsoth, who was close to Der Eigene — discussing the repeal of Paragraph 195 — was leaked to the press, the scandal intensified. Left-wing parliamentarians taunt him with shouts such as “Hot Röhm,” “Heil Gay,” or “SA, Trousers Down!”21, turning Röhm's sexuality into a weapon of political humiliation.

After Hitler consolidated power as chancellor in 1933, the SA's political usefulness declined. Its mass militancy and overt homosociality no longer fit the needs of a regime pursuing centralized, bureaucratic control. Röhm's open homosexuality and his push for power increasingly became liabilities to Hitler's new order.

By June 1934, Röhm's defiance and the SA's semi-autonomous power had become intolerable. During the “Night of the Long Knives” (June 30th – July 1st, 1934), Röhm and many of his top lieutenants were arrested and executed on charges of treason. Official statements condemned Röhm's “gravest neglect, conflicts, and pathological tendencies.”22 Hitler justified the killings as moral purification: “The Führer gave the order for the merciless excision of that ulcer; in the future, he will not allow individual persons with pathological tendencies to implicate and shame millions of decent people.”23 Nazi propaganda framed the purge as ethical cleansing — ridding the movement of “pathological” elements to restore its supposed moral integrity. In reality, it is now admitted that it served a dual purpose: eliminating a political rival and extinguishing any lingering tolerance toward homosexuality within the Nazi ranks.

After Röhm's purge, Heinrich Himmler assumed control of the SA and soon became Reichsführer-SS, head of the Schutzstaffel (SS) — another paramilitary organization that is responsible for Nazi state terrorism. Under Himmler, the SS replaced the SA as the regime's dominant force. This transition marked a decisive shift in sexual politics: while Röhm's era had permitted limited sexual privacy, Himmler's rule abolished it entirely. Homosexuality was now redefined as both a racial and moral threat. “Homosexual panic” became a defining feature of Nazi ideology and state policy.24

That same year, the Gestapo launched a large-scale campaign against homosexuals. They destroyed publications, raided clubs, collected denunciations, and called for the death penalty for gay people from public platforms and in newspapers. In response to homophobic sentiments of the masses, Paragraph 175 was amended to increase punishments for coercion, crimes involving minors, prostitution, and bestiality. The text of the law also replaced “unnatural vice” with simply “vice” — a change that allowed virtually anything to fall under its scope, including embraces and glances.25

In 1935, the official SS newspaper Das Schwarze Korps ran an article “Unnatural Indecency Deserves Death,” which defined homosexuality as a “degenerate and racially-destructive phenomenon.” It declared that present-day Germany should reach back to “the primeval Germanic point of view” by instigating “the eradication of degenerates.”26 These words spread far and wide, marking the beginning of a period of homophobic terror. Its victims were anyone who disagreed with the regime's policies and could be suspected — even slightly — of “vice.”

In 1936, Himmler established the Reich Central Office for the Combating of Homosexuality and Abortion. Simultaneously, the Nazi-controlled psychoanalytic establishment became complicit in this sexual policy. The Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute — systematically cleared of Jewish practitioners and critics of the regime — was reconstituted as the Deutsches Institut für psychologische Forschung und Psychotherapie (the Göring Institute) under Matthias Göring, a relative of Nazi politician and military leader Hermann Göring. By 1938, it offered conversion therapy against homosexuality and claimed hundreds of supposed cures among men referred by Nazi organizations.27

Those convicted under the new law were first imprisoned, then sent to concentration camps along with other “deviants” like sex-workers, homeless people, the mentally impaired, and the Jews. There, they were subjected to forced labor, sexual violence, and medical experimentation. Some of these experiments revealed an overt sexual, voyeuristic preoccupation on the part of their captors. To determine whether convicted homosexuals were “curable,” prison guards brought female inmates to male compartments and observed if the men would seize this opportunity to copulate. Doing so, they acknowledged that homosexual acts might be situational. If these traumatized prisoners showed no sexual interest in the opposite sex or consistently showed attraction to the same sex, they were deemed incurable and treated with escalating brutality.

In 1937, Himmler told SS lieutenants:

We must be absolutely clear that if we continue to have this burden [homosexuality] in Germany, without being able to fight it, then that is the end of Germany, and the end of the Germanic world. Unfortunately, we don't have it as easy as our forefathers. The homosexual, whom one called “Urning,” was drowned in a swamp. The professorial gentlemen who find these corpses in the peat-bogs are certainly unaware that in ninety out of a hundred cases, they have a homosexual before them, who was drowned in a swamp, clothes and all. That wasn't a punishment, but simply the extinguishment of abnormal life.28

Himmler opened his speech by meticulously citing statistics on homosexual men in German society.29 His obsession with the topic was evident as he insisted that any “impure” sex threatens the degeneration of the nation, the race, and the people. Yet beneath this lofty rhetoric lay his own fixation on other men's sex lives — a preoccupation that was itself sexual in nature, though far removed from what is commonly understood as such.

The Nazi regime's biopolitics of total control over sexuality assumed the racial and sexual hygiene of bodies, predominantly male. Ideally, soldiers should abstain not only from sexual relations with non-Aryan women, communists, or sex workers, but from sex altogether. This coexisted with a hyper-sexualized aesthetic of the body that could only be displayed among men — and with the reality of brutal, systematic, unpunished rape. Meanwhile, the private sphere dissolved as such. Men were obliged to publicly demonstrate their passionate devotion to the state to their comrades and older brothers.

These tendencies, often unconscious and unarticulated, became especially evident when Germany unleashed what would later become World War II. The Nazis intensified their persecution of homosexuals, introducing the death penalty for homosexual acts, legalizing the deportation of gay men to concentration camps, and debating compulsory castration.30 Yet simultaneously, they sent masses of single men to the front, creating conditions where these men could seek pleasure with — or at the expense of — one another. Women, meanwhile, were treated as second-class citizens: mothers who became obsolete with age, mere reproductive machines or instruments for sexual release.

Like Nazism itself, the Nazi male state (Männerstaadt) emerged from romantic ideals and white nationalism. Yet it had nothing to do with queerness: the Nazis imposed a homosocial ideal, glorifying brotherly and comradely feelings between men. Its sexual regime was characterized by homonarcissism — a radical rejection of anything different or non-homonormative. Under this regime, social outsiders — queers, Jews, non-Aryans, and women — were deemed conceptually and biologically inferior. The only solution for building a new society was the extermination of anything alien or “deviant.”

Fantasies about purity

The Nazis' homonarcissism was paradoxical: they persecuted homosexuality while encouraging male communities and homosociality — the unification of people based solely on gender identity, which also carries a sexual dimension (control of bodies, both their own and those of others). So what were the Nazis really fighting against when they stigmatized people as “deviants” and put pink triangles on their prison uniforms?

Klaus Theweleit’s Male Fantasies was among the first works to analyze Nazi sexuality without resorting to homophobia. His predecessors often linked Nazi hypermasculinity with homosexuality — as when Theodor Adorno claimed that “totalitarianism and homosexuality belong together.”31 Theweleit identified a glaring contradiction in this approach: conceptions of homosexuality are so diffuse, so shaped by defensive processes — even among analysts themselves — that the concept offers little real understanding of what homosexuality actually is. Instead, it triggers prejudices, false ideas, and personal defence mechanisms, leading to the reassuring but strained conclusion that homosexuals are always fundamentally others — aliens or enemies utterly unlike ourselves.32 Yet both otherness and alienness are relational. The objects of antagonistic feelings like fear or hatred are deeply rooted in those who experience them. Similarly, the object of fantasy cannot be separated from the one who fantasizes.33 The fact that the Nazis persecuted some homosexuals while glorifying others may reveal something uncomfortable about the Nazis themselves: their belief system was riddled with contradictions, some of which were indeed psychic in nature. But simplified conclusions that homophobia is perpetuated by closeted gays are absolutely misleading for understanding a complex system of oppression and its transhistorical appeal.

Theweleit draws on Guy Hocquenghem's Homosexual Desire, a pioneering text of queer theory. Hocquenghem centers homosexual desire on two key ideas: desire as a positive and creative (Hocquenghem drew primarily on Deleuze and Guattari), and the exclusion of the anus from sociality.34 Homosexual desire challenges normative boundaries and categories. It represents an “unformulated return of the libido”35 and undermines key forms of repression consolidated by the social exterritorialization of the anal area:

Whereas the phallus is essentially social, the anus is essentially private (...) The anus has no social position except sublimation. The functions of this organ are truly private; they are the site of the formation of the person. The anus expresses privatization itself (...) The constitution of the private, individual, “proper” person is “of the anus;” the constitution of the public person is “of the phallus.” (...) The anus does not enjoy the same ambivalence as the phallus, i.e. its duality as penis and Phallus. Of course, to expose one's penis is a shameful act, but it is also a glorious one, inasmuch a s it displays some connection with the Great Social Phallus. Every man possesses a phallus which guarantees him a social role; every man has an anus which is truly his own, in the most secret depths of his own person.36

In this context, Theweleit argues that “homosexual longing” is not simply one form of sexual desire among others — as liberal reformist arguments for tolerance suggest. Rather, anal penetration represents the opening of social prisons, admission into a hidden dungeon that guards the keys to the recuperation of the revolutionary dimension of desire.37

Here, “revolutionary” means “desire to desire.”38 From the perspective of the Nazis' seemingly monolithic social organization, this desire to desire — or desire for its own sake — was unacceptable. Yet they found it natural to violate others' boundaries in sophisticated ways. The Nazis' repression of the anal expressed itself in two forms: stigmatizing the passive sexual role as a sign of “moral decay,” and enforcing strict army discipline through heavy, uncomfortable uniforms, goose-stepping, and corporal punishment — particularly flogging.

At the same time, Nazis viewed homosexuality as more or less permissible for men with a “homosexual” disposition, or for men who were thought to engage in it as transgression.39 As a result, over half of those convicted under Paragraph 175 avoided punishment. The Nazis showed considerable tolerance toward party members and Aryan youths on trial, actively seeking acquittals for them. Many Nazi leaders — including Hitler himself — employed homosexual bodyguards, rendering these compliant gay men untouchable.40 Yet Nazi transgression reached its peak in the concentration camps. These spaces became a true homonarcissistic dystopia where homosexuals were exploited as objects of harassment, sadism, and both so-called “scientific” and sexual experimentation.

Psychoanalyst Elena Pasynkova, drawing on clinical work and activism in conflict zones like Palestine and Ukraine, notes the particular vulnerability of queer people when scientific knowledge about homosexuality is absent or excluded:

Sexualized jokes common in post-socialist and Western societies are rare in cultures where sexuality isn't constantly discussed. This doesn't mean same-sex relationships don't exist there. In Palestinian schools, for instance, such relationships are as common as in Western schools — a result of gender-segregated education and lighter punishment compared to extramarital heterosexual relations. Society overlooks them despite widespread awareness. Similarly, sociological studies show that outside the family, boys are more frequently targeted for rape due to greater accessibility and lesser consequences. In Arab communities less influenced by university education, homosexual tendencies may be expressed more openly, confusing Western observers. Men can display affection toward each other more freely — not perceived as sexual — because they lack the Western practice of monitoring every gesture and tone.

Theweleit and many researchers referring to him concluded that the Nazis were misogynistic. They sought to maintain the imaginary integrity of their male ego by oppressing the feminine within both their psyches and their social environment. This could be seen as an attempt to preserve the monolithic and pure ego, as well as a broader social and sexual homogeneity that asserts itself through the suppression of all that is heterogeneous.41 Several theories also link Nazi anti-Semitism with their misogyny, as the idea of “Jewish” as “feminine” was prevalent in nationalist circles.42

However, when femininity becomes the subject of positive propaganda — through the creation and enforcement of the ideal Nazi wife image43 — the concept of femininity itself as a social and sexual construct becomes problematic. The suppression of both the “feminine” and the anal shares a common thread: their perceived alienness, impurity, fluidity, and affectivity. In this sense, the Nazis' aversion to queerness can be understood as a rejection of non-monolithic gender and sexuality — forms that are simultaneously transgressive and transgressed, desiring and desired.

Far-right violence involves a paradoxical form of transgression: it is restrictive rather than liberating, fundamentally contradicting transgression itself. After all, transgression not only violates the norm but also confirms its significance. Therefore, the Nazi uprising can be seen as a form of recognition, rather than of disavowal. The Nazis violated their own laws, including sexual norms, normalizing rule-breaking from a position of ego-driven infallibility and permissiveness.44 Notably, Röhm — like many others convicted under Paragraph 175 — claimed he was bisexual and only masturbated with other men, thus technically avoiding violation of the law.45 In other words, he did not engage in anal sex as an act of desire-driven transgression. Without affection or openness to new experiences, transgression becomes destructive and fruitless, leading to extreme egocentrism and totalitarianism.

Fascinating and sexless

Nazi aesthetics embody this totalitarian drive — the means and methods the regime used to present itself and mesmerize its followers.

In her essay Fascinating Fascism, Susan Sontag examines Leni Riefenstahl, a key figure in the Nazi regime and Hitler's favourite film director (“my perfect German woman,” as he called her). Riefenstahl's iconic films, Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938), glorified aggressive masculinity and Olympic physical perfection, as well as the supposed biological and physical superiority of the Aryan race. The two parts of Olympia are tellingly titled “The People's Festival” (Fest der Völker) and “The Festival of Beauty” (Fest der Schönheit). According to Sontag,

[f]ascist aesthetics include but go far beyond the rather special celebration of the primitive (...) More generally, they flow from (and justify) a preoccupation with situations of control, submissive behaviour, extravagant effort, and the endurance of pain; they endorse two seemingly opposite states, egomania and servitude. The relations of domination and enslavement take the form of a characteristic pageantry: the massing of groups of people; the turning of people into things; the multiplication or replication of things; and the grouping of people/things around an all-powerful, hypnotic leader-figure or force.46

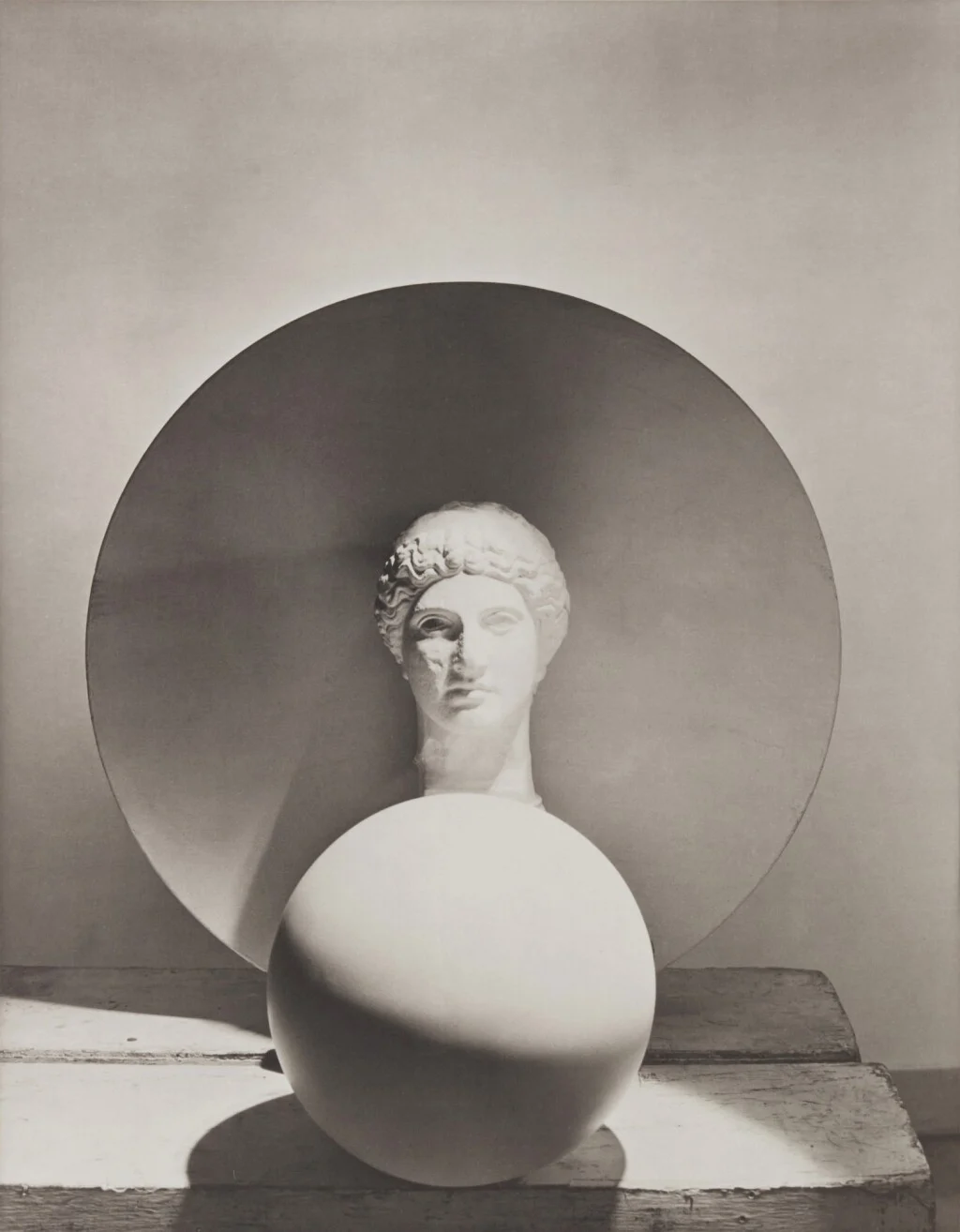

The figures marching through German streets and sports stadiums resemble clean-shaven, muscular androgynes, resembling the most common types of sculpture in Ancient Greece. They seemed almost devoid of genitals or other human characteristics. Dressed in uniforms or Olympic suits, they appeared to have stepped directly from a Nazi poster. Even when straining with effort, their images remained iconic and polished to perfection — so much so that one was not able to tell whether they were looking at a real person, an erotic doll, or a machine of erotic domination. As Sontag writes, “[t]he fascist dramaturgy centers on the orgiastic transactions between mighty forces and their puppets, uniformly garbed and shown in ever swelling numbers. Its choreography alternates between ceaseless motion and a congealed, static, ‘virile’ posing. Fascist art glorifies surrender, it exalts mindlessness, it glamorizes death.”47

The aesthetic of physical perfection is, at its core, deeply utopian — not because physical perfection doesn't exist or because bodies lack the right to be beautiful. Rather, its utopianism lies in combining the “sanctimoniously asexual” with the “(in a technical sense) pornographic.”48 The “triumph of the will” is actually a triumph of aestheticizing political life, as Benjamin characterized fascism49: a performative expression of bodily superiority and purity — not only racial and physical, but also gendered and sexual.

The central myth of Nazi aesthetics is radical bodily equality — achievable only through eugenics and racial hygiene. Constrained by this myth, individuals discipline themselves to appear pure, ideal, and flawless. Bridging these observations with contemporary clinic, Elena Pasynkova continues:

Once positioned within a power structure, a subject has limited options for navigating the position this power grants them. In any social structure, sexual relations are strictly prescribed at the mythic level — though this doesn't directly coincide with the structure itself. However, following Foucault, if we emphasize visibility as a form of control over sexuality, we find this control across various modern regimes, regardless of their authoritarianism or how subjects perceive themselves. Widespread social media only exacerbates this.

Large-scale modern media such as propaganda posters, mass cinema, television, and radio, which — even when they allow for subjective reading and ambiguity — still profoundly shape individual identities. Under Nazism, subjects were obliged to express their gender in an “ideal” way that combined sterility with mass appeal perfection. At the stage of gender performance, Nazism's main objective was to embody the unique and exceptional “Aryan spirit” — as opposed to the materialistic eroticism of the Weimar Republic and the USSR, which were considered the two most sexually degenerated states. Propaganda presented an aesthetic ideal of a desirable yet immaculate body, aligned with post-Christian values and free from signs of gender and sexual diversity.50

Christina Wieland has described the striving for aesthetic utopia that was integral to the fascist state of mind.51 The fascist utopia seeks to establish a total state of mind (Wieland references Bollas) that eliminates all opposition and claims access to all objects (Chasseguet-Smirgel):

This “moral void” simplifies violence. The empty subject must find a victim to contain the void “and now a state of mind becomes an act of violence (...) To accomplish this transfer, the Fascist mind transforms a human other into a disposable nonentity, a bizarre mirror transference of what has already occurred in the Fascist's self experience.”52

Annihilation of the other creates a sense of emptiness and purity, particularly regarding one's own body, gender, and sexuality. However, ultimate purity is unattainable: “contamination” awaits the individual from the moment they acquire speech. Language itself is inherently ambiguous, to say nothing of the psychic upheavals that occur in intersubjective relationships and human vulnerability to nature. To reproduce itself, the fascist state of mind requires total war, which fuels its narcissistic ambitions by achieving superiority over the other and destroying the other as a phenomenon.53 Victory in total war enables one to achieve a peculiar state of eternal life. In this state, by breaking ties with others and overcoming the relational dimension of one's existence, the subject becomes a monolithic object that does not need to sustain itself as a living being. A drive toward total annihilation of the other resembles “the Nirvana principle”54, which — unlike the pleasure principle — seeks to eliminate affection to avoid the fluidity and variability usually associated with enjoyment.

The sexualized other embodies the differences and paradoxes that totalitarianism struggles with in relation to the body, gender, and sex. The Nazis excluded and labeled this other “dirty” not only because of its perceived repugnance and disorderliness, but because its existence threatened purity itself. The sexualized other is perceived as alien because inhabiting this queer body, gender, and sexuality means accepting yourself as you are and recognizing that others can derive pleasure from it — just as you potentially can.55 This subverts the concept of homonarcissism, which is based on the superiority of a homogeneous body, gender, and sexual act. Homonarcissism cannot tolerate this subversion, since any homogeneity, even represented by idealized images of brutal male statues, is merely someone's fragile and bitter fantasy.

Nazism does not create the homonarcissist; it beckons him to emerge from the shadows, insecure and lacking self-confidence. The Nazi-type leader summons him from an imagined past of “former glory” and guides him into violent claim to power in the present:

A cult of aggressive male inferiority already exists and may develop further as the authoritarian leader's strengthened role fuels hysteria among his subjects — including men. Against this backdrop, one might ask: What is masculinity? Why does its definition seem so simple and almost intuitively understandable, even to many psychoanalysts trained to comprehend the limits of such identity categories?”

Queer people remain targets of authoritarian regimes.56 However, liberal democracies are not immune to authoritarian and totalitarian backlash. Fascism adapts to modern conditions by embracing new media, technologies, psychologies, and ideologies. Sexualized fascism is firmly rooted in homosocial and gender-narcissistic communities, such as the “manosphere.” These communities promise ultimate self-expression but demand constant visibility and competition with others. This reproduces similar dynamics of surveillance, conformism, and exhibitionism that once defined Nazi mass culture.

Yet like the Nazis, contemporary traditionalists longing for “natural” masculine omnipotence, as well as opponents of transgender and queer people and people of color within the gender and sexual rights movement, develop an obsessive need to break rules and establish your own rather than show sincere care for one another or find genuine joy in being vulnerable before another human. This reveals their membership in a group whose members share essentially nothing except their genitals — which themselves vary in shape and size.

Among gay men (and other men), masculinity becomes violent and narcissistic when it loses its authenticity and hardens into a rigid category hostile to anything fluid and queer. Choosing monolithic masculinity — whether consciously or not — is like stepping back into the closet from which gay men once emerged. In these challenging circumstances, critical analysis must neither ignore the Nazi past nor be romantic and overly optimistic about contemporary authoritarian tendencies. Instead, we must learn from these tragic lessons and continue doing so, taking small but meaningful steps forward toward the dysphoria mundi that Paul B. Preciado aptly describes as “forms of life that announce a new regime of knowledge and a new political and aesthetic order from which to think through the planetary transition.”57

Images: Horst P. Horst, George Hoyningen-Huene

Notes

1. This publication was produced with support from History Unit at n-ost and funded by the Foundation Remembrance, Responsibility and Future (EVZ) and the Federal Ministry of Finance (BMF) as part of the Education Agenda on NS-Injustice. The authors wish to express their gratitude to Romain Pinteaux (Schwules Museum Archive, Berlin) for his valuable contributions to the discussion of this text and his scholarly editing.↰

2. Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure, Duke University Press, 2011, 148. ↰

3. We interpret gender in the spirit of Judith Butler as “performatively constituted by the very “expressions” that are said to be its results.” See Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, Routledge, 1999, 33.↰

4. While discussion of the fabrication of such eroticized fantasies of Nazism is beyond the scope of this essay, a valuable source on the topic is Laura Catherine Frost’s Sex Drives: Fantasies of Fascism in Literary Modernism, Cornell University Press, 2002. ↰

5. Laurie Marhoefer, From “gay nazis” to “we’re here, we’re queer”: A century of arguing about gay pride (2016), online here. ↰

6. Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume 1, translated by Robert Hurley, Pantheon, 1978.↰

7. Laurie Marhoefer, Racism and the Making of Gay Rights: A Sexologist, His Student, and the Empire of Queer Love, University of Toronto Press, 2022. ↰

8. See Andrew Hewitt, Political Inversions: Homosexuality, Fascism, and the Modernist Imaginary, Stanford University Press, 1996, Chapter 3.↰

9. Adolf Brand, “Über unsere Bewegung,” Der Eigene 2 (1898): 100–101. ↰

10. A 2023–24 exhibition at Schwules Museum, Berlin, entitled “Coming to Terms with the Past: Sexual Violence against Children and Adolescents in the Name of Emancipation,” provided a nuanced glimpse into this uncomfortable page of queer history in Germany.↰

11. Harry Oosterhuis, “Medicine, Male Bonding, and Homosexuality in Nazi Germany,” Journal of Contemporary History 32, no. 2 (1997): 197. ↰

12. Richard Bessel, Political Violence and the Rise of Nazism: The Stormtroopers in Eastern Germany, Yale University Press, 1984, 153. ↰

13. Völkischer Beobachter, July 8 (1928). ↰

14. “Doch sind unsere Gedanken bei Dir, Kamerad!” Hamburger Tageblatt, December 26 (1931). ↰

15. Harry Oosterhuis, “Review of: Wackerfuss, A. (2015), Stormtrooper Families: Homosexuality and Community in the Early Nazi Movement,” Social History 42, no. 4 (2017): 567. ↰

16. Oosterhuis, “Review of: Wackerfuss, A. (2015). Stormtrooper families: Homosexuality and community in the early Nazi movement,” 566. ↰

17. Richard Plant, The Pink Triangle: The Nazi War against Homosexuals, Henry Holt, 1986, 62. ↰

18. Eleanor Hancock, “‘Only the real, the true, the masculine held its value’: Ernst Röhm, Masculinity, and Male Homosexuality,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 8, no. 4 (1998): 616–641.↰

19. Hans Peter Bleuel, Sex and Society in Nazi Germany, Lippincott, 1973, 97–98; Joachim C. Fest, The Face of the Third Reich: Portraits of the Nazi Leadership, Pantheon Books, 1970, 144.↰

20. Bleuel, Sex and Society, 97–98; Fest, The Face of the Third Reich, 144. ↰

21. Sven Reichardt, Faschistische Kampfbünde: Gewalt und Gemeinschaft im italienischen Squadrismus und in der deutschen SA, Böhlau Verlag, 2002, 680; Andrew Wackerfuss, Stormtrooper Families: Homosexuality and Community in the Early Nazi Movement, Harrington Park Press, 2015, 182. ↰

22. Robert Biedroń, “Nazism’s Pink Hell,” Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum, online here. ↰

23. Biedroń, “Nazism’s pink hell.”↰

24. See Geoffrey J. Giles, “The Institutionalization of Homosexual Panic in the Third Reich,” in Social Outsiders in Nazi Germany, ed. R. Gellately and N. Stoltzfus, Princeton University Press, 1992, 233–255.↰

25. Hancock, ““Only the real…,’” 636. ↰

26. Michael Burleigh and Wolfgang Wippermann, The Racial State: Germany 1933–1945, Cambridge University Press, 1991, 191–192. ↰

27. Clayton John Whisnant, Queer Identities and Politics in Germany: A History, 1880–1945, Harrington Park Press, 2016. ↰

28. Burleigh and Wippermann, The Racial State, 193. ↰

29. Burleigh and Wippermann, The Racial State, 192. ↰

30. Geoffrey J. Giles, “The Denial of Homosexuality: Same-Sex Incidents in Himmler’s SS and Police,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 11, no. 1 (2002): 248–249. ↰

31. Theodor W. Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life, Verso, 2005, 46. ↰

32. Klaus Theweleit, Male Fantasies. Vol. 1: Women, Floods, Bodies, History, University of Minnesota Press, 1987, 54–55. ↰

33. Theweleit, Male Fantasies. Vol. 1, 45. ↰

34. Klaus Theweleit, Male Fantasies. Vol. 2: Male bodies — Psychoanalyzing the White Terror, University of Minnesota Press, 1989, 312. For the theoretical context of the anal method and the phenomenon of anal normalization in identity politics, see Paul B. Preciado, Anal Terror: Notes on the First Days of the Sexual Revolution, Bodony and Futura, 2015.↰

35. Sigmund Freud, Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality and Other Works. Vol. 7, Penguin Books, 1977, 148.↰

36. Guy Hocquenghem, Homosexual Desire, translated by Daniella Dangoor, Duke University Press, 1993, 96–97. Online here.↰

37. Theweleit, Male Fantasies. Vol. 2, 313. ↰

38. Theweleit, Male Fantasies. Vol. 2, 313. ↰

39. Theweleit, Male Fantasies. Vol. 2, 327.↰

40. Giles, “The Denial of Homosexuality,” 263–265. ↰

41. On the combination of the heterogeneous and the homogeneous in fascism see George Bataille, “The Psychological Structure of Fascism,” New German Critique 16 (1979): 64–87. ↰

42. Jay Geller, “Freud, Blüher, and the Secessio Inversa: Männerbünde, Homosexuality, and Freud’s Theory of Cultural Formation,” in Queer Theory and the Jewish Question, ed. D. Boyarin, D. Itzkovitz, and A. Pellegrini, Columbia University Press, 2003, 40–72. ↰

43. Leila J. Rupp, “Mother of the Volk: The Rise and Fall of the Women’s Movement in Nazi Germany,” Signs 3, no. 2 (1997): 362–379. ↰

44. On this point, see Theweleit, Male Fantasies. Vol. 2, 325. ↰

45. Manfred Herzer, “Communists, Social Democrats, and the Homosexual Movement in the Weimar Republic,” Journal of Homosexuality 29, no. 2–3 (1995): 214. ↰

46. Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism,” in Under the Sign of Saturn, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1980, 91. ↰

47. Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism,” 91. ↰

48. Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism,” 92. ↰

49. Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, Harvard University Press, 2008, 41. ↰

50. James Bernauer, “Sexuality in the Nazi War Against Jewish and Gay People: A Foucauldian Perspective,” Budhi: A Journal of Ideas and Culture 2, no. 3 (1998): 149–168. ↰

51. Christina Wieland, The Fascist State of Mind and the Manufacturing of Masculinity: A Psychoanalytic Approach, Routledge, 2015. ↰

52. Wieland, The Fascist State of Mind 203.↰

53. Wieland, The Fascist State of Mind, 23. ↰

54. Barbara Low, Psycho-Analysis, George Allen & Unwin, 1920, 73. ↰

55. See Alenka Zupančič and Anna Fishzon, “What is Sex?” MIT Learn (2018). Online here. ↰

56. For example, see Nina Khrushcheva, “Homophobes and Autocrats: Dictators Depend on Order,” Project Syndicate (2021), online here. ↰

57. Paul B. Preciado, Dysphoria Mundi, Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2025. ↰