The Community of Capital: On Jacques Camatte [II]

Michele Garau

Philosopher Michele Garau concludes his two-part engagement with Jacques Camatte's critique of the revolutionary tradition. Whereas Part I retraced the key stages of Camatte’s trajectory, exploring his divergence from Bordigist dogmatics and his parallels with fellow travelers such as Giorgio Cesarano and Tiqqun, the present essay offers a sustained reflection on the concept of the “anthropomorphosis of capital” and its implications for communist struggle. According to Garau, it is this problem of the “recomposition” of the species in accordance with the needs of the economy that will send Camatte in search of an escape from the closed dialectic of revolution and counterrevolution from which the capitalist order nourishes itself. In order to construct its outside positively, “any revolutionary gesture must extract itself from the dialectic of confrontation, from the reproduction of antagonism.” As Garau is careful to insist, the urgency of this task need not lead us either to quietism or pacifism. It does, however, force us to rethink revolutionary rupture as a desertion at once anthropological and ontological in nature. To this end, building upon previous articles such as “Without Why,” Garau highlights the powerful analogies between Camatte’s critique of capitalist representation and the destituent lineage of thought extending from Reiner Schürmann to Giorgio Agamben and the Invisible Committee.

Other languages: Italiano, Español

I would like to return to some of the issues raised by my previous essay to better explain how Camatte's departure from Marxism played out. More specifically, I am interested in seeing where, in deviating from the canon of historical materialism, an adherence to the perspective of revolution and the question of communism was still maintained. It seems to me that it is in this interlude, during which the "theory of the proletariat" has been cast aside but the horizon of communist revolution still remains, that we find the most powerful weapons Camatte’s legacy has to offer the present. To make a long story short, these consist primarily of texts that appeared between 1973 and 1974 in the second series of Invariance: “The Wandering of Humanity, Repressive Consciousness, Communism,” “Decline of the Capitalist Mode of Production or Decline of Humanity,” “Against Domestication,” and “This World We Must Leave.”1

The key to this shift in perspective concerns the category of "productive forces" and its connection to man. The "anthropomorphosis of capital" spells the destruction of earlier human being in its very substance, disintegrating and recreating both individuals and their social bonds. Individual and communal nature are inseparable, in the dimension of Gemeinwesen and the world of capital that captures it. The domestication described by Camatte therefore comes to its completion when capitalist domination, substantiated in a "material community," finally recomposes a humanity that it had ripped apart and fragmented at the beginning of its becoming. Capital is anthropomorphized and man is capitalized. Adhering to the Marxian perspective — in this case, that of the Grundrisse — Camatte initially regards this decomposition also as the gestation or preparation of a social human being of the future, the liberation of his potential. This is the well-known civilizing function of the capitalist mode of production of which, in spite of everything, we still find traces in Capital and Community:

[A]t the beginning there are beings who dominate things; at the end, things become beings. This is the total movement of the movement of alienation, which arose over millennia. Nonetheless, this is only a negative aspect of the phenomenon: the total loss of man. There is a positive aspect, namely, the growth of the productive forces which, at a certain level, create the "possibility" of an emancipated being, or of another social form — communism — just as at the beginning of the movement of alienation, the positive side was the production of the individual.2

This coincidence loses solidity when the concept of the productive forces comes to be questioned in its polysemy and in all that it left unresolved. Marx can define capital and its development as a revolutionary agent only insofar as he is willing to assume that the economic productive forces and the creative force of humanity collide, at least partially and temporarily. On the one hand, there is the growth of economic value, and on the other, the universalization and polyvalence of human faculties on the other; according to Marx, the two become fused at a precise moment in the historical cycle of the capitalist mode of production. The productive forces overwhelm and break up their previous historical base, pushing beyond its boundaries in a constant upheaval that removes all obstacles. As Camatte points out in This World We Must Leave, it is no coincidence that the capitalist revolution is grafted onto a "project of the species" marked by the separation and liberation of the subject from every constraint and all content. The revolutionary nature of capital presents itself as the destruction of the limited character of individuals and of the relations of production at the same time.

From here, communism can be understood as the final outcome of an increase in production unable to be halted by its own base, the latter being no longer a given but always also a result to be called into question. The proletariat, within this framework, carries the laws of capitalism to their conclusions without any regard to preserving the integrity of its transitional social forms. The concept of transition — with which the cause of socialism has been preoccupied for over a century — turns out, moreover, to be precisely the opposite of the concept of rupture. It is for this reason that, according to Camatte, alongside his better known idea of self-abolition of the proletariat we also find in Marx an idea of the "self-abolition of capital." The real question, however (for Camatte as well as for us), lies in whether the becoming at issue here really has anything to do with a dynamic of communist transformation, or, on the contrary, it is a mechanism already implicit in the processes of capitalization. The indefinite and cumulative movement that cannot be judged "from any height," this fury of dissipation that (as we have seen) unconsciously resembles the idea of revolution as infinite transition, as Saint-Just conceives it — does it really encounter an insoluble contradiction in the development of its own dialectics? Does its immanent movement truly contain crisis and rupture?

Historical materialism is a glorification of the wandering in which humanity has been engaged for more than a century: the growth of productive forces as the condition sine qua non of liberation. But by definition all quantitative growth takes place in the sphere of the indefinite, the false infinite. Who will measure the "size" of the productive forces to determine whether or not the great day has come?3

If we are faced with a "limited form of production" then its limit must be internal, i.e., it must be a determinate negation that arises from the economic movement. After all, if this limit originated separately or outside of it, it would no longer fit the pattern in question. As Bordiga (and Engels before him) noted, in Marx there is in fact no philosophy of exploitation: class antagonism takes shape in perfect fulfillment of the law of the exchange of equivalents, without any extra-economic supplement. The fact that Maximilien Rubel, another interlocutor very present in Camatte's analysis, felt the need to unmask the ethical presuppositions of Marx's categories (exploitation in primis) offers a further confirmation of the problem. Otherwise, if we were accept that the productive forces underlying the revolution were the same as those deployed by capital, it would only be a matter of correcting the political mediator and the accompanying social structures so as to adjust them to the appropriate material level, something the capitalist form is perfectly capable of accomplishing without any rupture necessary. This was in fact the case with fascism, understood as a decisive stage in the fulfillment of the community of capital. In other words, just as the universalization of the proletariat and the creation of a community rooted in labor did not point the way to the realization of any socialist program (except for a mystified one), so the revolutionary process modeled upon the productive forces has as its only referential subject the economy itself:

It merely carries-out whatever the ruling powers need to do in order for the community of capital to achieve the determined development of its laws. The contestation of the old structures leads to the introduction of more adequate structures.4

Briefly, we can say that this dynamic — which Marxism has penetrated and predicted, while misunderstanding its sign — corresponds to what Camatte calls "wandering." At its climax, it coincides with the forward flight [échappement: runaway] of capital. The productive capacity achieved no longer has in it anything creative, not even collaterally, precisely because it is the escalation of a disembodied relationship, freed of any human content. Production for capital can only have a completely destructive impact on the resources of humanity, an obvious decline. The "biological revolution" evoked by Camatte (and by Giorgio Cesarano, in the same period) concerns precisely this bifurcation through which the "capital phenomenon" confronts the organic life of the species with the possibility either of extinction or decline. What results is the liberation of capital and the wandering of humanity.

The revolution that results from this escalation of development to a higher level, capable of absorbing every obstacle and taking itself to ever greater heights, is a revolution of capital that has surpassed its every limit and no longer knows any exteriority. For the same reason, historical materialism and Marxism — in the form of "development theory," i.e., the idea of the accretion of productive forces in itself — merely sanctifies this wandering. As Camatte repeatedly observes, as the political arc of capitalist modernity and its ideological options become increasingly reduced to a single representation, like rackets and indifferent variables, the left and its cult of progress represents the perfect epiphenomenon of the emancipation of value, whereas various conservative or even reactionary currents find themselves unilaterally defending this or that human content, only to be disqualified by their one-sided application, as well as the anti-egalitarian and repressive implications of their claims. This is a complex and controversial issue that appears at several points in Camatte's work, particularly where he addresses the theme of community.5 The same insight can be applied, albeit in a different sense, to the revaluation of utopian-romantic currents of anti-capitalism in which a strong communitarian motive prevails, such as the anarchic thought of Gustav Landauer, Martin Buber, or Franz Rosenzweig — the whole constellation of revolutionary theory that Michel Löwy sought to reopen, in studies that Camatte unsurprisingly cites.6 Alongside these references there is another parallel, which bears a certain affinity with the Ernst Bloch’s reflections in his Nonsynchronism and the Obligation to its Dialectics.7 Although a detailed consideration of this rich essay would take us far afield, the common conviction of the two authors resides in their claim that the devaluation and even suppression of persistently "non-contemporaneous" elements that survive in the present, interrupting its synchronization to a single rhythm, constituted a serious failing of the workers' and communist movement during its struggle against fascism:

We wish to insist on this claim of community on the part of the currents of the right, but especially of the extreme right, which has nothing to do with Marx's theorization in this regard, but testifies to its imperious necessity. It was a proof of enormous theoretical weakness on the part of all the currents of the left not to have been able to deal with the question of community on the basis of Marx's work. They responded by merely skimming over the questions posed, without grasping their depth; the same happens on the level of knowledge, particularly with regard to scientific development.8

For Camatte, the test case for the confrontation with the community is the analysis of the revolutionary phenomenon in Russia. Of course, to even raise these topics with our comrades of solid Marxist faith (the same ones, of course, who exalt the municipalist experience of Rojava, without sensing any contradiction) demands that we confront the cold irony of the "clan-like" character of any peasant community, whether in Russia or elsewhere. In his seminal study on the peasant commune and the Russian revolutionary movement — which does not conceal its debt to the research of Camatte — Pier Paolo Poggio had already underscored the short-sightedness of those who think that the form of the soviet came into being all of a sudden between 1905 and 1917, as if dropped into the factories of St. Petersburg purely through the application of the theoretical schemas of "Western" socialism. This communitarian-communist dimension was equally strong in the Makhnovshchina. The independence and cooperative character that characterized agricultural labor in the mir and artel are enlivened by forms that the revolutionary process spontaneously gives itself once the peasants are wrested from the land and concentrated in the factories:

For quite some time, scholars of the Russian revolution have placed the soviets in an indefinite limbo, or else have sought to explain them through the German or Italian workers' councils, making them organs of management of industrial production. This inability to grasp the scope and nature of the political forms manifested in the course of the revolution of 1905 and 1917 also stems from the lack of knowledge of Russian history and from the curtain of silence that Marxism, hegemonic in the Russian intellectual milieu at the end of the century, had imposed on the theme of communal forms and the leap of the CMP.9

The persistence of such a peasant world leaves its mark in Slavophilic and populist utopias,extending all the way back to Herzen, Bakunin, and briefly in Lenin himself.10 This model of utopia differs from the legacies of the "Asiatic mode of production" in its rejection of the transcendent and external unity of the state, as well as its reconciliation, at least partially, of individual autonomy and the communal bond. As both Poggio and Camatte emphasize, the rejection of "capitalist socialization" in its early days (reflected in the populists) simultaneously rejects both its atomizing effects and its annulment of the individual in a depersonalizing massification. There is nothing more collectivistic and unifying than capitalist civilization, writes a communist poet of the past century:

[T]he person is a "mask," a social being that distinguishes itself from others in a representation that has its own written and introjected rules. The integral personality reacts to this process of increasing individualization and denaturalization of man. It opposes the contemporary and complementary process of atomization and socialization. The integral personality is the opposite of the specialized individual, of the individual who has a role in work and in life in general [...]. The integral personality is defined by the harmonious and omnilateral development of its faculties. Only by recognizing himself in the community, by being united with nature and the cosmos, can man realize himself as a creative individuality and extrude his faculties; only in this "environment" can he expand his humanity, which shrivels up in separation and is reduced to spectral subjectivity.11

This idea that the internalization system of the "community of capital" entails both the reduction of time and the reduction of the person is a recurrent theme in many authors. The intertwining between objectification, the quantification of experience as a measurable extension, the ontological division between "Man" and "Nature," the "monadic" and self-founded image of the Subject, has distant roots. The simultaneous construction of "Nature" as an object and the delimitation of the separate Subject — one mark of which is the newfound primacy of vision — is an essential feature of the Cartesian foundations of modern thought. Martin Heidegger, in The Age of the World Picture, wasamong thefirst to call attention to this problem. Less explored is its connection with the exhaustion of the relational conception of the person. We find traces of this reflection in the works of Marxists like Jason W. Moore, as well as in the writings by Jerôme Baschet (where it comes with more concrete political implications), particularly in his Basculements.12 The central contention is that, if the gesture that isolates the reasoning individual from other beings is the same one that opposes him to nature, one can only conceive of a political autonomy adequate to the present on the basis of a radical heteronomy and ontological dependence. And (even if it seems trivial) this involves unhinging this autonomy from the gears of the modern regime of time and progress:

[W]e must remember that political autonomy and the autonomy of the subject have nothing in common, and are even antithetical. To assume a relational conception of the person is to recognize that "there are only heterodetermined forms of existence," because they are traversed by ties with other beings, places, and environments, with collective histories and the symbolic materials they carry. Political autonomy would then be the autonomy of necessarily heterodetermined forms of life.13

It is worth dwelling for a moment on the "potential death of capital" and its relation to revolutionary negation. Camatte links the disappearance of revolutionary negation to the closure of what we could call the "revolution-counterrevolution cycle." This closure is explained both by the structure of the capitalist contradiction, whose two dialectical poles, capital and labor, mutually reinforce one another, as well as by the domination of capital which, when it desubstantializes and becomes "representation," is bolstered by the absorption of all that opposes it. The shift from negation to affirmation to which Camatte alludes, the use of term "schism" (borrowed from Bordiga, yet expanded in its implications), along with his idea of abandoning a world in which the structure of antagonism has now been internalized, all belong here.

When Bordiga speaks of “schism” he means the preservation of Marxist doctrinal invariance against the ideological influences of an adverse environment during periods of counter-revolution in which any creative contribution or innovation would already be a betrayal. The overwhelming force of the opposing class and the halting of every cycle of proletarian offensive does not permit us to step beyond the "hermeneutic." For Camatte, things are different: either the experience of the communist movement and its revolutions (on an unapologetic balance sheet) is deemed to have favored the development and penetration of the capitalist form in geographic and social areas in which it was previously unknown, or else, the schism must be carried further. It must be pushed beyond the grounds — science, progress, enlightenment — that communism shared in common with the rationality of capital, a terrain on which the alternation between revolution and counter-revolution formed an integral part.

The dynamic of conflict forced capitalist domination to transcend and overcome the law of value, absorbing the opposition of classes. But above all, at the most general level, valorization has fed upon the vital reserves of organic energies, of creativity, to the point of emptying subjects and rendering them their own "tautologies." The prostheses and symbols that derive from the externalization of human abilities are structured in a "combined body" that discerns, in the construction of the person as a mask, even prior to the production of artifacts, a form of "proto-work." The living sense encoded in social "know-how" (to paraphrase Cesarano) now has primacy over the extraction of living labor. This explains Camatte’s interest in the paleontological research of André Leroi-Gourhan which, as Louis Bredlow has pointed out, aligns with certain insights found in Cesarano’s work, particularly in his Critique of the Utopia of Capital.14 The important point here is that, for humans, the history of externalization and alienation originates in the Paleolithic Age, at the moment that the frontal pole (the mouth from prehension, and the hands from gait) is liberated, opening the way to stereotypical patterns of technique and language. Of course, this shift is not inherently negative until it spins out of control, since it occurs in homination, i.e., in the detachment from a natural unity, whether true or merely supposed. However, with it comes a leap from evolution to inorganic mutation, completely transferred to another, hostile object. The chain of expropriation through gesture and speech here converges, from a given moment onwards, with the becoming of capital and its operational concatenations, one that, in a mutual reinforcement between the two paths, leads capital to become a biological phenomenon, to anthropomorphosis:

Marx explained the becoming of Homo sapiens in its communitarian, social, and individual dimensions; Leroi-Gourhan did the same thing with regard to the paleontological dimension and, insofar as he had the same methodological approach, he integrated, perhaps without his knowledge, all that Marx had produced. However, a real knowledge of the latter would have allowed him to understand that the phenomenon of externalization, of dispossession that he highlighted had a name: capital. He would also have perceived that the dynamic internalization of symbols was linked, fundamentally and in an accelerated manner, to the final phase of the domination of capital, the one in which it itself becomes man. In the end, both phenomena contribute to domestication, a phenomenon that characterizes Homo sapiens.15

On the other hand, this also leaves the inorganic prosthetic system with nothing further to feed upon. Since these prostheses were nourished by the human capacity for creative, evolutionary responses to the stimuli of experience, when the latter becomes absorbed, blocked, and enters into decline, capital and its system are likewise threatened with death. It is potentially dead already.

Today, in order to construct its outside positively, any revolutionary gesture must extract itself from the dialectic of confrontation, from the reproduction of antagonism. As Tiqqun observes, we no longer find any figure of the "Great Outside": the proletariat qua transgression or abnormality that must be repressed. To what else does the idea of "destituent power" respond, if not the need to find an alternative to the idea of "anarchy" as transgression and infraction of the norm? If we return to the well-known reflections on transgression offered by Bataille, Blanchot, and Foucault, one can glimpse the mutual implication of the limit and its breakdown, the impossibility of an anomie that is not a sacrifice of the subject.16 Transgression reinforces the law. This is no doubt why, in his recent studies on power, Giorgio Agamben attempts to deactivate the ontological-political machine of opposition, while also grappling with the aporia in Foucault’s work between the grip that power maintains over the subject and those counter-conducts that enact a transformation of individual life. The dual structure that is foundational to power captures the exception by positing dualities whose poles are presented, fictitiously, as unrelated: norm and transgression, sovereignty and original anarchy, social contract and civil war. The negative horns of these antinomies, however, are always the result of a primary capture, and the image of anarchy and civil war that power presents as its "other" is in truth its shadow. Leveraging one alternative against the other is therefore always a losing strategy, since it remains fully responsive to the terms on which the machine operates, its apparatus. For this reason, "true anarchy" must break with the endless cycle of revolts that generate new powers, revolutions which are invariably followed by counter-revolutions. It must defuse the false image of an original anarchy — as Pierre Clastres did — but above all, it must find a new lexicon:

This is what marks the difference between anarchy as destituent power and anarchy as transgression. [...] Now, according to Agamben, transgression brings into existence what it transgresses, that is, the structure of subjectivity as an instance that always goes beyond and exceeds itself. It commands and obeys. And this also, perhaps above all, in the infraction of its own commandment — in self-sacrifice.17

"Becoming revolutionary" and the Revolution, it could be said, remain distinct albeit connected dimensions. In Camatte's trajectory there are different stages, but the tendency to abandon and secede from the world ends up prevailing as an alternative to the possibility of revolution: a liquidation of the revolutionary perspective understood as an epiphenomenon of capitalist modernity. Only by stepping out of the process of civilization in which the revolutionary principle takes part is it possible to overcome the stalemate in which the life of the species is entangled. Nevertheless, there are moments of transition in Camatte’s journey during which the concept of revolution incorporates this transition from negation to affirmation, a creative moment designating the construction of communist poles outside the world of capital:

Until now, the revolutionary movement has positioned itself as the negative of the movement of capital. The positive-affirmative work was seen only in the beyond of the revolution. Now it is a question of positing this beyond as susceptible to being experienced, of positing the necessity of its realization in order to oppose the order of capital with a positive-affirmative subversion.18

We hear echoes of this intuition in the project of disjoining the constituent and the destituent tension within the revolutionary events, which is explicitly worked out in certain passages of the Invisible Committee. On this view, the revolutionary seasons of yesteryear have always contained, in act and in speech, both of these souls, which it is now a matter of disentangling.19 As we have seen already, the revolutionary question in its bourgeois version is, according to Camatte, an organizational and constitutional problem. The entire theme of organization as the basis of social form would, in itself, therefore be an expression of bourgeois civilization: institutions and value representations that inform subjects according to norms and models would, in this sense, be a substitute for the community as being. For this reason, the unitary measure of value responds, in the history of the capital phenomenon, to the formation of stereotypes and mediators of social movement that shepherd the manifold features of men's lives back to a fixed framework. These frameworks and representations are first imposed from without, before becoming immanent features of the social body. The collapse of value thus attests to a more general crisis of the principle of organization in the various aspects of human life, a crisis of normality based on measurement. In short, according to Camatte, beyond the economic sphere, value depends on representation; yet as capital becomes abstract and integrates all barriers, it loses any stable referent. Thus, in an isomorphism between the material base and the other spheres of existence, norms and limits are peeled away and rendered inoperative:

The law of value imprisoned human beings, forcing them into stereotypes, into fixed modes of being. (...) By engulfing the general equivalent, by becoming its own representation, capital removed the prohibitions and rigid schemas. At that point human beings are fixed to its movement, which can take off from the normal or abnormal, moral or immoral human being. The finite, limited human being, the individual of bourgeois society, is disappearing. (...) The human being in the image of capital ceases to consider any event definitive, but as an instant in an infinite process.20

Every principle of theoretical synthesis thus remains only a form of repressive consciousness, at the expense of experience and phenomena. Every truth is an etalon, a gauge, a unit of measurement, a value, an equivalent or abstraction that stands against the "totality of life." Truth is only a truth that fixes itself and totalizes against experience. Since the onset of this breakdown, there has been a need to recompose unity in a manner that is mediated and repressive, namely, through the functions of hierarchization afforded by the state, the movement of the economy, and science. From this point of view, the abolition of the gold standard or the rise of finance are merely emanations of an epochal twilight of principles that has innumerable refractions. Admittedly, in Camatte's pages this correspondence often gets lost in suggestive metaphors without being rigorously and thoroughly developed. It seems to me that, beyond the many biological and naturalistic references, there is a profound analogy between Camatte’s thesis and Reiner Schürmann’s idea of a deposition of hegemonic principles and "economies of presence," along with its associated conception of ontological anarchy and destitution.21 This analogy is evident, first of all, in the basic diagnosis advanced in Schürmann’s Le principe d'anarchie and reiterated in Tiqqun, namely, that metaphysics has always provided power with its formal structures and principles. Secondly, just as the concept of a crisis of representation responds to the end of a cycle of "autonomization of the intermediate movement," the destitution of hegemonic principles brings to fruition a blind trust in language that devalues phenomena by anchoring them into fixed frames of gestures, words and things. In both cases, the loss of the common frame appears as the necessary result of an oppositional double bind that erodes the edifice of power itself from within. What survives today are epochal phantoms destituted by an internal abyss, which are at the same time representations of capitalist civilization that, by dint of extending themselves, become inflated and enter into crisis. The crisis of representation is, first of all, a crisis of capitalist society. In both cases, therefore, it is a question of confronting an internal fragility of the machinery of power that is no longer transitory but has become epochal. In both cases, this entails actively forcing the outcome: detaching ourselves from an automatic body that is potentially dead (Camatte), letting the event of the decline of principles be, without why (Schürmann). As Camatte often reiterates in the early seventies, a revolution capable of coming to terms with this scenario must reject any theory of action that inhibits experience by making a fetish of words or identities: that is, it must reject the primacy of a first philosophy that finalizes or justifies action. This would be a revolution that does not legitimize itself in the name of a higher principle, or by reference to a regulative unity (pros hen). “One doesn’t bring power back down to earth in order to raise oneself above the heavens.”22

It is quite clear that all references to Man, to the naturalness of the species against the "biopathic" effects of capital contradict this perspective. This is what Gianni Carchia reproached Camatte for: Life, Man, and Nature are terms so steeped in metaphysics as to be generally unsuitable for dwelling on its dangers. However, it is important to note that, beyond the "primitivist" and prescriptive outcomes that undoubtedly surface throughout the trajectory of Invariance, there is a certain approach to the themes of community, of the historical past, of experience and life whose legacy still remains open. In it, we find a lens that allows us to grasp something of the sensible [sensibile] nature of many contemporary revolts, their reliance on perceived, partial, and unjustifiable truths. Whether we like it or not, the loss of any intellectual and discursive monopoly over political facts, and in particular over the practices of contestation of society, is a fact that we would have to be blind not to perceive. In Camatte's writings on the matter, there is still much to take in.

First published in Italian on Machina, April 12th, 2022.

Translated by Ill Will, in collaboration with the author.

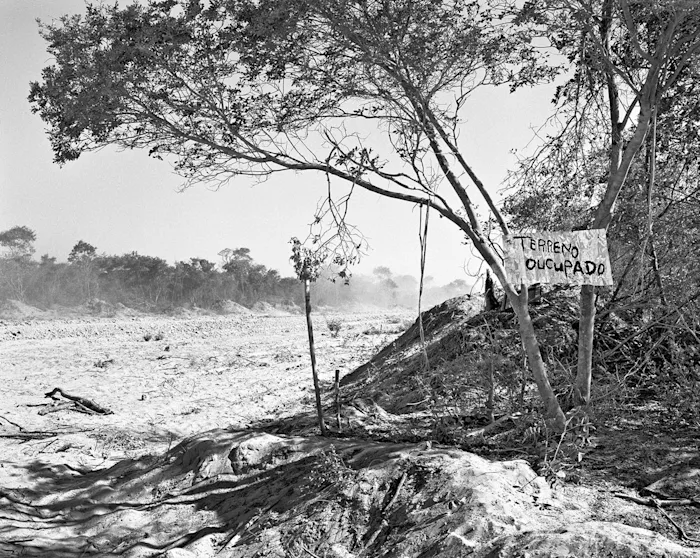

Images: Jo Ractliffe

Notes

1. English editions are available in Jacques Camatte, This World We Must Leave, Autonomedia, 1995. Three of the texts mentioned are combined in this volume under the heading “The Wandering of Humanity.” —Trans. ↰

2. Jacques Camatte, Capital and Community. The Results of the Immediate Process of Production and the Economic Work of Marx, translated by David Brown, Ch. 6, “Capital and Material Community.” Online here. ↰

3. Jacques Camatte, The Wandering of Humanity, Black & Red, 1975. Online here. First published in Invariance, Series II, no 3, 1973. ↰

4. Jacques Camatte, La revolution integre (1978), first published in Invariance, Series III, no 4. Online here.↰

5. “Community and Communism in Russia” (1972). First published in Invariance, Series II, no 4, 1974. An English translation by David Brown (1978) is online here.↰

6. See Michel Löwy, Redemption and Utopia. Jewish Libertarian Thought in Central Europe, Verso, 1992. —Trans.↰

7. Ernst Bloch, Nonsynchronism and the Obligation to its Dialectics (1932), translated by Mark Ritter, New German Critique, no. 11, 1977, Duke University Press. Online here.↰

8. Jacques Camatte, Épilogue au Manifeste du Parti communiste (1993), published in Invariance, Series IV, no 9. Online here.↰

9. Pier Paolo Poggio, Comune contadina e rivoluzione in Russia: l'obščina, Jaca Book, 1978, 195. ↰

10. This influence is very relative in Lenin, who soon applauds the benefits of industrialization, but also in Bakunin, who sees in the obsçina afactor of backwardness. Instead, what characterizes populism, beginning with the agrarian commune, Poggio explains, is a similarly forceful rejection of the state and nascent capitalism that finds its own articulation prior to the anarchist tradition, one also reflected in parts of Russian revolutionary socialism.↰

11. See Poggio, Comune contadina e rivoluzione in Russia, 249. Here Poggio specifically addresses the Slavophile utopia of I.V. Kireevsky and Michajlovsky, comparing their view of personality to that of the young Marx. [The poet in question is Heiner Müller. —Trans.]↰

12. Jason W. Moore,Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital, Verso, 2015; Jérôme Baschet, “Conception relationnelle de la personne, communauté et autonomie politique,” in Itinérances, edited by J. Rafanell i Orra, Divergences, 2018. Online here; Jérôme Baschet, Basculements: Mondes émergentes, possibles désirables, La Découverte, 2021. ↰

13. Baschet, “Conception relationnelle,” 25. ↰

14. L.A. Bredlow, “De la machine sociale à la révolution biologique,” Lundi matin, June 23rd 2020. Online here. The original version of the text, in Spanish, was published in the second issue of the Barcelona magazine Mania in 1996. ↰

15. Jacques Camatte, A proposito di Leroi-Gourhan (1986), in Comunità e divenire, Gemeinwesen, 2000, 149-150.↰

16. See Maurice Blanchot and Michel Foucault, The Thought of the Outside, Zones, 1998. ↰

17. Catherine Malabou, Au voleur! Anarchisme et philosophie, PUF, 2022, 308-309. ↰

18. Jacques Camatte, “Dalla negazione all’affermazione” [“From Negation to Affirmation”] in Verso la comunità umana, Jaca Book, 1968, 315.↰

19. The Invisible Committee, Now, Translated by Robert Hurley, Semiotexte, Ch. 4. Online here.↰

20. Camatte, “The Despotism of Capital,” in The Wandering of Humanity. Online here. ↰

21. [On Reiner Schürmann and the collapse of epochal principles, see Michele Garau, “Without Why: The Existential A Priori of Destituent Action,” Ill Will, October 2nd, 2021. Online here. —Trans.]↰

22. The Invisible Committee, To Our Friends, Trans. Robert Hurley, Semiotexte, 2015, Ch. 3. Online here.↰