The Good, the Bad, and the Militant

Luhuna Carvalho

Other languages: Türkçe, 中文, Français, Português, Ελληνικά

The situationists once claimed they had a father they loved, DADA, and a father they rejected, Surrealism. For many of us, Toni Negri was both. Too young to have witnessed them first-hand, the Italian seventies form one of our last reigning myths. Whether we know it or not, most of our experiences of struggle, from the squats to the squares, have taken place within its remnants and fragmented repertoires, as the only real collectivity we’ve known.

The Negri we loved was the Negri who sidelined a promising and comfortable academic career to become an agitator. It was the Negri who taught us how the rage, anger, despair, hate, and alienation we felt was nothing but a feverish desire for both a different life and a different world, nothing but a strange and profound passion for our comrades, nothing but a thorough and obsessive dedication to the abolition of the tyranny of capital. It was the Negri who claimed that ricominciare da capo non significa andare indietro (starting over again doesn’t mean going backwards), transforming Potere Operaio into Autonomia, establishing a method of rupture that celebrated the proletarian refusal of the melancholic and institutional memory of the left. It was the Negri who read every concept of vulgar economics as a category of antagonism. It was the Negri who showed us a dignity, ardor, and joy inherent in the act of struggle that is out of reach for the cynicism of critique. It was the Negri who took Marx’s claim that communism was “the real movement of abolition” in a literal way, grasping how moments of struggle were also moments of communion, and hence were also instances of something to come.

The Negri we rejected, with an impatience reserved only for those one loves, was the Negri of the Sisyphean chase after the next collective subject, each new hypothesis dissolving into smoke, one after another. It was the Negri who claimed that every social fad was a novel expression of “resistance,” without ever really explaining why or how. It was the Negri who turned post-operaismo into a bland sociology. It was the European Union Negri, the universal basic income Negri, the constituent Negri, the democratic Negri, the accelerationist Negri, etc.

There is, in reality, no opposition between the balaclava Negri and the citizen Negri. Upon his death we have to admit, in all honesty, that such a distinction was our own invention. Negri was thoroughly consistent. The continuity in his thought lay in how his Beckettian optimism was intrinsically woven into his philosophical and political work.

It all began with Classe operaia’s legendary red paragraph, Tronti’s “copernican turn”, now almost a psalm: “we must invert the problem, change the sign, restart from the beginning, and the beginning is class struggle.” It was struggles themselves which had forced capitalists to create capitalism and their most advanced expressions still direct capitalist development. The English translation of Tronti’s seminal statement, however, has always sounded slightly awkward. In the original one reads lotta di classe operaia (industrial class struggles), not just lotta di classe (class struggle). The primacy of struggles was grounded on the specific social being epitomized by the Italian post-war industrial working class, rather than on labor as whole. The spontaneous and creative antagonism of this industrial working class came from a singular conjunction between economic inclusion and political exclusion that only really came into its own within the closed space of the factory. The political ontology of operaismo was founded on the difference between the operai and the working class as such.

Negri’s take on Tronti’s theory of the primacy of struggles over capital abolished this difference, a gesture at once brilliant and cursed. The essence of such antagonism wasn’t any sort of productive labor per se but rather the very specific conditions of separation and alienation suffered by those operai. The extension of capitalist command over social reproduction meant that that separation and alienation could now be found everywhere.

In observing the shift whereby class antagonism spread from the factory into the metropolis, Negri developed the conceptual tools to name, arm, and organize such diffuse antagonism. In doing so he developed a theory of a communism that was immediate and immanent to struggles in themselves. Communism was not the prize awaiting the endless drudgery through the haphazard stages of dialectical materialism, it was already here, present in the violent, radical, and collective intelligence taking place within a thousand acts of antagonism, insurrection, and communization.

The absolute primacy Negri accorded to struggles gave a positive content to the refusal of labor. Behind shopfloor sabotage and metropolitan subversion there was a proletarian form of labor at pains to materialize. This idea would form the basis of Negri’s ontology throughout the following decades. “Self-valorization” was one of its first names, “multitude” one of its last.

This pervasive worker’s antagonism throughout the social sphere was evident during the seventies, but once Italy’s long May came to a close, such a primacy of struggle seemed less and less defensible. How could Negri’s “positive content,” implicit in proletarian refusal of labor, express itself when such refusal of labor was no longer evident? If Negri’s method was to sustain a social, non-factory based, primacy of struggles, then it had to become a fully fledged theory of contemporary social life. Post-operaismo came to see every little twitch of the social body as “self-valorization” and as a possibility of “resistance”, without ever developing a thorough criteria by which to assess such a claim. The end result was that “resistance” was everywhere and nowhere at once.

Negri’s critics often accused him of not being dialectical enough. Negri’s enthusiasts — and Negri himself — would gladly agree. But if he can be accused of anything, it is perhaps of being too dialectical. If Tronti was, in his own words, first a politician and only then a “thinker”, Negri was — proudly — first a militant and only then a philosopher. Negri wrote for the “movement,” aware that addressing that subject was, in a way, a method of creating it. There was no standpoint of reason external to the subjective movement of the working class, to the affirmation of its positive content, and hence the consistency of Negri’s conceptual work found both its ground and confirmation precisely within those struggles themselves. “Self-valorization” and “multitude” were valid concepts precisely inasmuch as Negri’s idea of what constitutes a movement came to recognize itself within them, and within the political processes presupposed in them. In other words, the “multitude” existed only when it believed itself to exist. It belongs to the nature of such a “movement” to presuppose its own material and historical conditions (state and capital). Its triumphant antagonism existed only inasmuch as it shared a playing field with the opposing team, but this meant that every goal scored meant an acceptance of the rules of the game. This is why Negri was never an anarchist, nor did he ever claim to be one, even though his writings were always coloured by a vague libertarianism. For him, concepts and ideas only existed when they became movement, and a movement only existed when it articulated with the concrete institutional realities of its period — be it the Italian Communist Party or the European Union, be it Fiat’s Mirafiori or neo-liberal entrepreneurship.

However, as insurrections came and went, the internal coherence of any instance of “movement” seemed to dissipate even further. Negriism functioned on the presumption that the dynamic core of contemporary politics lay in the oscillation between constituent and constituted forms. But today power affirms itself through its capacity to destroy, dismantle, and annihilate its own social body, through austerity, ostracism, or outright war. The integrity of any positive revolutionary substance could only hold as long as that constitutional dialectic held too, even if Negri’s permanent “constituent power” aimed to stop it in its tracks. Negri’s unwavering optimism slowly started to taste ever more bitter, as if the only remaining strategy was to fiercely repeat “we are winning” in the face of obvious defeat. Autonomia, for Negri, existed as a way of unshackling the PCI from its orthodoxy and complacency, not as a way of destroying it. But the EU is not the PCI, and bitcoin is not Mirafiori.

Negri was right in a way that few others ever were, namely in his insistence that communism is always already present. His life was, in his own words, a “communist life.” To claim that a life is communist is not to claim that communism was realized in the ethical integrity of one’s actions and affects, or to believe any single personal history can stand for the meaning of communism. It means, rather, that one has chosen to live within the question of communism, within its singular and collective joys and trials. Negri’s death, along with Tronti’s and others, poses a question of continuity, especially for those who, in one way or another, were raised within militant traditions indebted to these towering figures. In a world which allows for little hope, their legendary tenacity is at once inspiring and burdensome. Perhaps the only honest way to remain faithful to it is, in our own terms, to once again perform the rupture inherent in their thought. It is precisely because we can cherish Negri’s optimism that we can also suggest that, right now, to start over again might have come to mean going back — going back to the question of what a communist life is.

December 2023

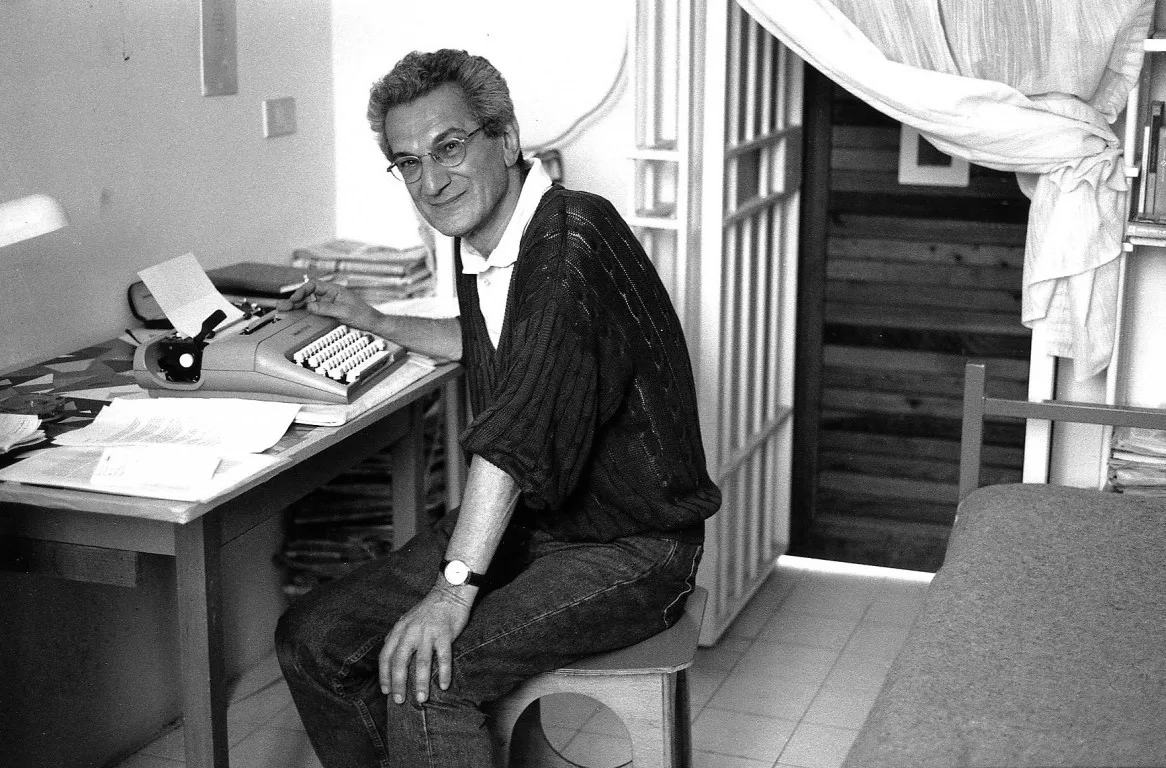

Images: Haus-Rucker-Co., P. Magnon