The Movement of Refusal

Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen

Other languages: Deutsch, Français, Español

The last decade and a half has been a time of unrest. As the French political anthropologist Alain Bertho has described in his book Le temps des émeutes, the early 2010s saw a sharp increase in the number of protests.1 Strikes and demonstrations took place throughout the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, of course, and food riots were not uncommon in the Global South. However, after 2008, there was both a quantitative and qualitative shift, with far more widespread protests, demonstrations, occupations, riots and uprisings taking place in far more places around the world. As Dilip Gaonkar writes, these protests and riots are moving north, and are now also occurring in liberal democracies.2

In retrospect, we can point to the Arab revolts, the so-called Arab Spring — which broke out in December 2010 in Tunisia and quickly spread to Egypt and a number of countries in North Africa and the Middle East in the early months of 2011 — as the decisive turning point. These events marked the transition from a period characterized by an almost total absence of radical dissent to a situation in which the ruling order was challenged.3 In particular, the images from Cairo, where thousands of people took to the streets, occupying Tahrir Square and demanding Mubarak’s removal, punched a hole in the “capitalist realism” and “just move along” discourse of late capitalist globalisation.4 From Cairo, the protests spread to southern Europe, with demonstrators occupying squares in Athens, Madrid and Barcelona, demanding an end to the austerity imposed by national governments at the behest of the European Commission, the IMF and the European Central Bank. Such policies were enacted in the wake of the financial crisis, which quickly turned into an economic and social crisis in many southern European countries. In summer 2011, London was the scene of violent riots, followed that autumn by Occupy Wall Street’s occupation of Zuccotti Park in Manhattan. As the first wave of protests died out or was crushed, others erupted elsewhere.

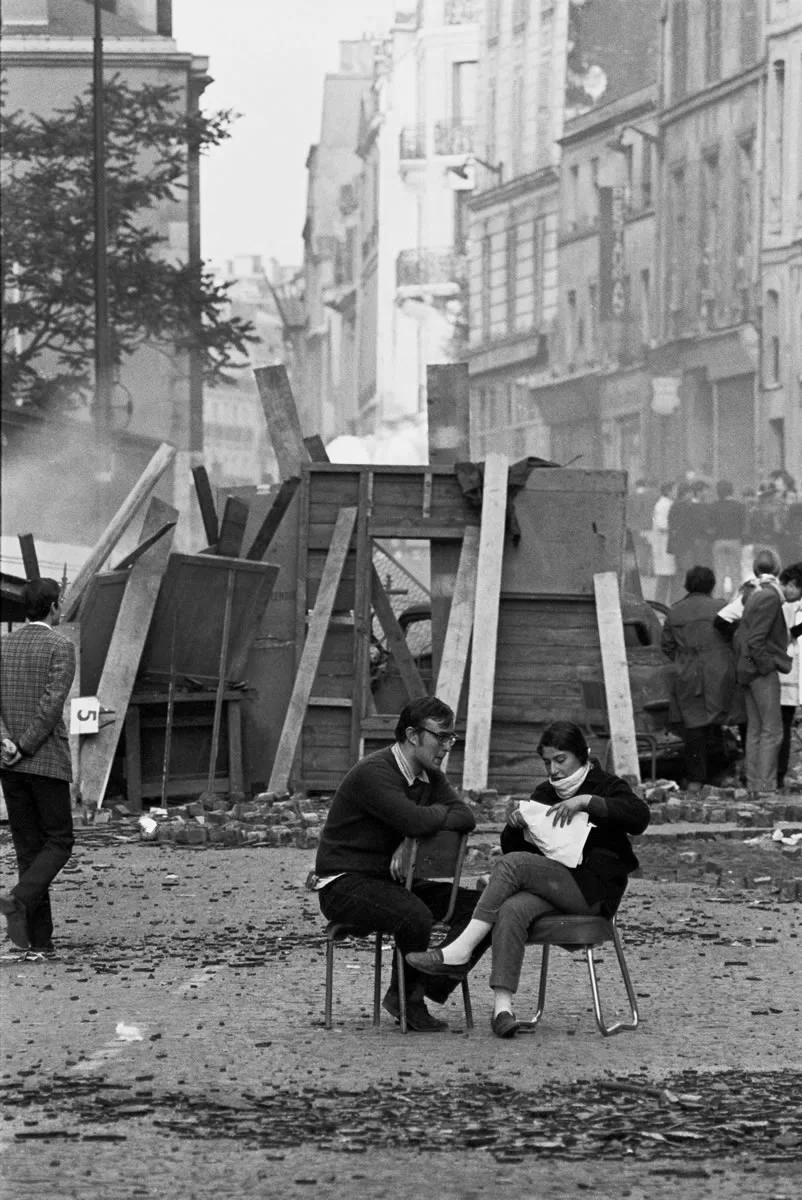

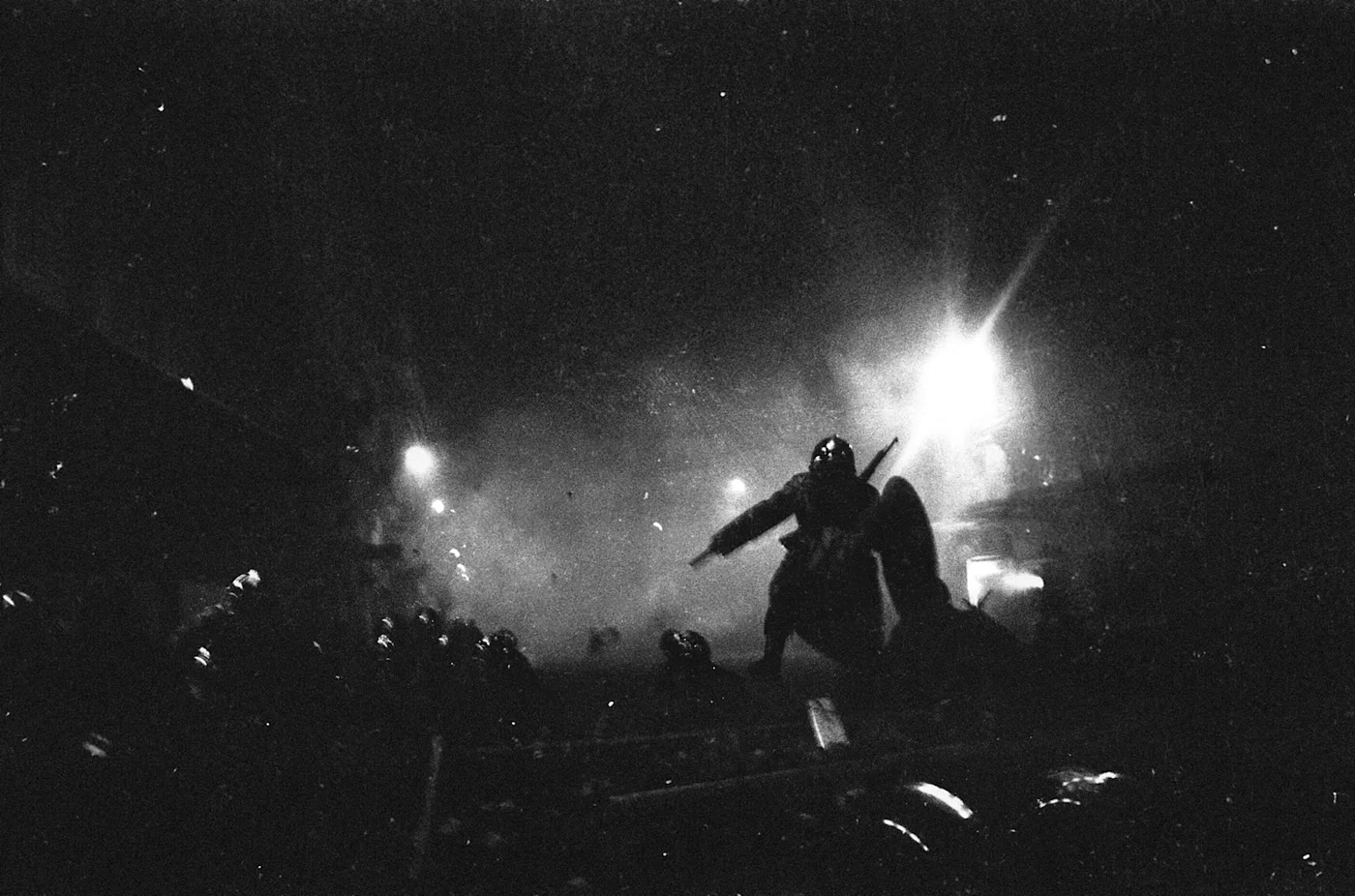

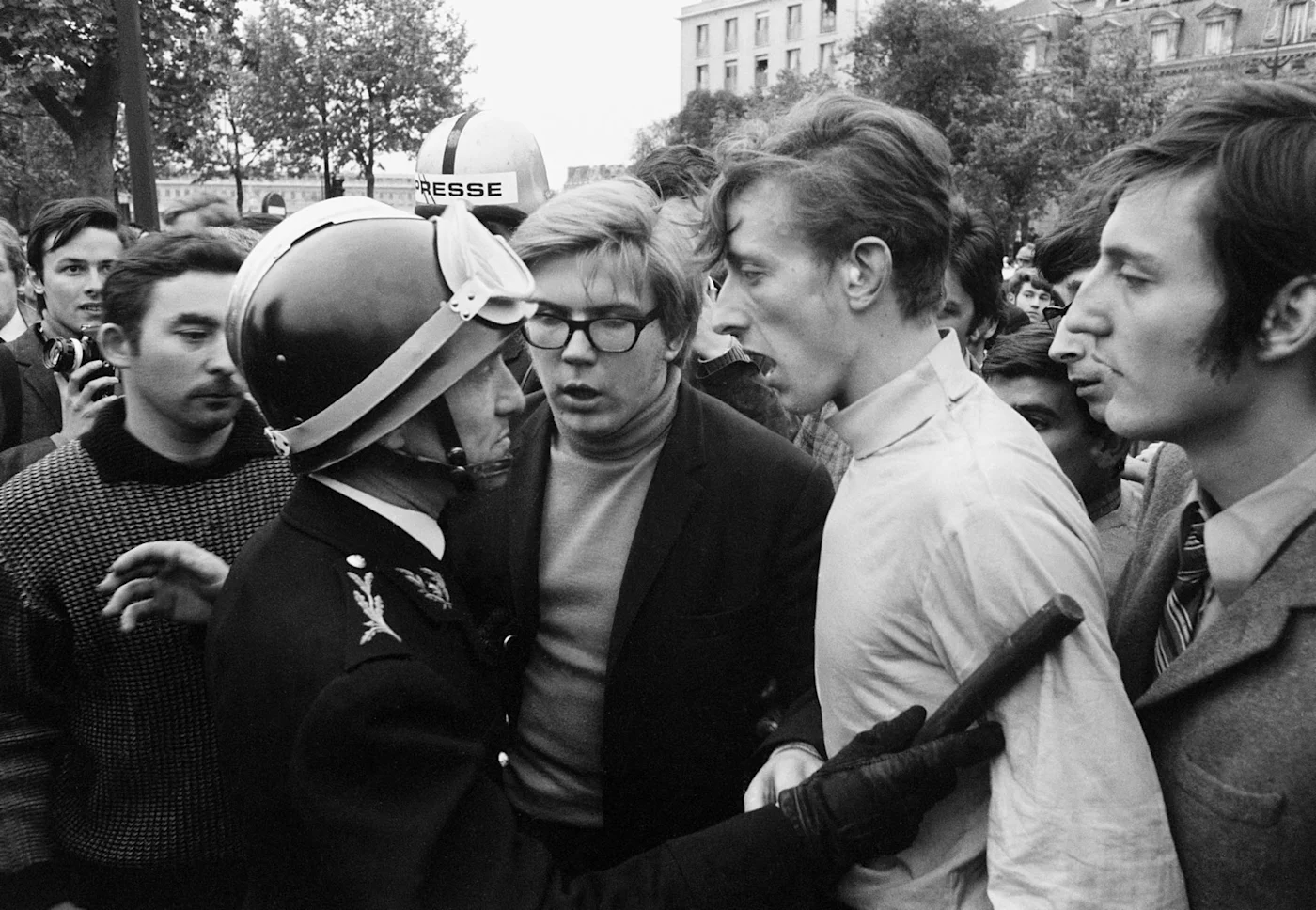

The years since 2011 have been characterized by a discontinuous global protest movement that has moved back and forth across the world in a staccato pattern of shifts and leaps. The protests have been so widespread that both 2011 and 2019 were each proclaimed to be “a new May ’68,” and Time magazine chose the protester as its “Person of the Year” in 2011.5 Some of the most prominent episodes of this new cycle include the Chilean student protests of 2011–2012; the Brazilian transport resistance of 2013; the Ukrainian Maidan movement; Nuit debout and the Gilets Jaunes in France; the democracy movement in Hong Kong; the Sudan Commune; the Lebanese uprising; protests against racist police in the US, from Ferguson in 2014 to Minneapolis in 2020; the Iranian “Women, Life, Freedom” revolt of 2022; and the protests against Macron’s pension reform in France in April 2023. Even the coronavirus pandemic and local lockdowns did not end the new cycle of protests and the “underground Bildung” that has been emerging for more than a decade now.6 This was made abundantly clear by the response to the murder of George Floyd, which saw the most widespread protests and riots in the US since the late 1960s. A police station was burned down, and wealthy neighborhoods, not usually sites of protest, saw looting and fighting between police and protesters.

During 2021–2022, we briefly seemed to be in an intermezzo marked by post-pandemic exhaustion and the re-emergence of inter-imperialist strife, which threatened to bury simmering discontent and desperation in a new-old Cold War binaries that made acts of dissent difficult. But it was only a matter of time before people were on the streets again. Sri Lanka was followed by Iran, and France is once again the scene of mass protests. Wherever we look, we see the socio-economic conditions for more unrest.7 Manufactured culture wars, often presented as intergenerational conflicts, are only the tip of the iceberg. Beneath the surface lies a crisis-ridden capitalism that seems unable to act strategically in the face of an accelerating climate crisis and stalling growth, which just never really seemed to gain any momentum after 2008. Representatives of the global bourgeoisie, like Deutsche Bank’s research team, have seen the writing on the wall and, like Bertho, now speak of “an age of disorder.”8 However, despite realizing there is a crisis, it seems extremely difficult for the bourgeoisie to develop any real plans for a major transformation of the economy. As the neo-Leninist collective of Alex Hochuli, George Hoare and Philip Cunliffe write in The End of the End of History, the ruling classes seem unable to unite around a plan. Today, the Situationist Gianfranco Sanguinetti would not be able to write a report, under the guise of “the Censor,” on how the ruling class will save the capitalist status quo through staged terrorist attacks and false flag operations.9 Instead, Hochuli, Hoare and Cunliffe describe our current situation as the “nervous breakdown of neoliberalism,” in which Big Tech billionaires dream of traveling into space, while large parts of the political establishment would like nothing more than to hold out “four more years,” or at most another decade or two (Biden instead of Trump, etc.).10 It is not even possible to unite around “green capitalism.” But the genie is out of the bottle. The economic crisis is now taking the form of inflation, and none of the normal solutions, such as raising or lowering taxes or stimulating or curbing consumption, seem to work. Rather, there seems to be an unarticulated consensus that a great deal of existing capital must be destroyed. Moreover, the longer the crisis lasts, the greater the level of investment in military and counter-insurgency equipment.11 The COVID lockdowns provided governments around the world with a whole series of newfangled tools with which to monitor and combat discontent, so there is every indication that conflict will become even more confrontational — such is the prediction of the Conspiracist Manifesto.12 People are increasingly prepared to resort to violence, not least in America. To put it bluntly: every housewife in Florida now seems to be an Oath Keeper, and many businessmen are Proud Boys. Trump was a prelude, a figurehead. Now the real forces are taking shape.

Many commentators have noted that protests over the last ten to twelve years have been characterized by a striking absence of concrete demands, and have rarely involved the drawing-up of actual political programs. The left communist Jacques Wajnsztejn, of Temps critiques, disparagingly calls the phenomenon “insurrectionism.” Following the 2011 London riots, the Leninist neo-Marxist Slavoj Žižek wrote that the events were “a blind acting out,” an expression of a more generalized deficiency.13 As Žižek put it: “opposition to the system cannot be formulated in terms of a realistic alternative, or at least a coherent utopian project, but can only take place as a meaningless outburst.”14 Even when the opposition is expressed by a pessimistic, postmodern slogan of defeat — “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than an alternative to capitalism,” as Fredric Jameson put it in his analysis of the major structural transformations he had previously labeled postmodernism — or even when Nuit debout, in the Place de la République in Paris in spring 2016, rejected this nihilistic messaging, they did so in a kind of abbreviated form (“Une autre fin du monde est possible,” “Another end of the world is possible”), yet without any corresponding utopian or political vision.15 This is not the “another world is possible” of the alter-globalization movement, which was in itself a far cry from the many socialist mottos of the twentieth century; instead, we simply get “another end of the world is possible.” While Nuit debout rejected postmodern defeatism, this was not in the service of a vision of another world. There does not seem to be anything behind capitalism and its crisis, nor anything approaching on the horizon, either. Rather, what has prevailed is a resigned, slightly sarcastic critique. Capitalism was (and is) undoubtedly digging its own grave, but also ours. The ongoing climate crisis is only the most obvious expression of that process — but, if nothing else, we can fight against capitalism’s preferred method of ending the world. According to the occupiers of the Place de la République, dissent is still possible.

Nuit debout’s slogan is highly revealing. While the new protests take many different forms, what they have in common is less a shared vision of a different society and more their refusal itself. Of course, alternative forms of society are discussed in some movements, such as the American and French ones; but these never arrive at anything that can be said to constitute a genuine program. The protesters simply refuse to accept the situation.

We need to analyze this refusal. Waves of uprisings crash invariably into brick walls, yet our language for understanding them does not help us break through them. We are confronted with a linguistic obstacle. In what follows, I will present a theoretical and historical trajectory in which a revolutionary vocabulary inherited from prior generations gradually recedes and disappears. This trajectory tells the story of the “victory” of the workers’ movement, followed by the disappearance of “the worker” and a long economic crisis. I will end by introducing the notion of refusal as presented by Maurice Blanchot and Dionys Mascolo in 1958 when confronted with de Gaulle’s state coup in the midst of the Algerian war. Perhaps revisiting the notion of refusal will enable us to step closer to our current situation and identify a new approach to the difficulties we experience today.

Yellow Vests

There is no doubt that the mass protests, demonstrations and uprisings of the last decade have differed from each other. Donatella Di Cesare is right to ask whether we can use one single term for these divergent struggles.16 Hardt and Negri noted in 2013 that “each of these struggles is singular and oriented toward specific local conditions” but also went on to argue that the protests did indeed constitute a “new cycle of struggles.”17 Di Cesare agrees. Many of the protests acknowledged each other across borders and contexts, with Occupy activists mentioning the Tahrir protesters in Cairo, and Egyptian revolutionaries ordering pizzas for the park occupiers in Manhattan. Syrian revolutionaries supported the Yellow Vest movement and proclaimed that “our struggle is common. [...] You cannot be in favor of a revolution in Syria while siding with Macron.”18 Not only did the protesters refer to each other, but the protests also shared tactics — the approach utilized in Egypt, which saw the occupation of squares and roundabouts, spread first to Spain and the United States, and then to Turkey, Ukraine, and France, among other places. Later in 2019, the frontliner tactics from Hong Kong began to spread elsewhere.19

Among the most striking features of this new cycle of protests has been their loose organization and absence of demands. Of course, as Hardt and Negri pointed out, virtually all uprisings, demonstrations and occupations are directed against specific local or national conditions, but in the vast majority of cases recent protests have not been accompanied by overarching political demands. In some protests, this lack of a program formed part of a more elaborate tactic, encompassing various inclusive intersectional meeting tactics. This was the case, for example, in the Occupy movement, which — as Rodrigo Nunes argues — had a distinctly “horizontal dimension.” In other cases, this lack of any program has seemed more like an expression of desperation or outright aversion to politics.20

A good example is the Gilets Jaunes movement. The French roundabout occupations started in November 2018 as a protest against the Macron government’s proposed fuel tax surcharge, which was to come into force in 2019. However, the protesters never presented anything that could be said to constitute a genuine political demand that the Macron government could possibly fulfill. In this sense, the protests were anti-political — understood not as a pejorative description but as a term for the rejection of mainstream politics. Dissatisfaction with the new tax immediately extended to frustration with growing economic inequality and the rural-urban divide. There were too many demands and no — or too many — leaders or spokespersons. The protests did not take the form that political protests usually take in France, nor were they mediated by the organizations that have traditionally assumed the role of representatives of social classes, political groups, and professions. None of the major parties could claim with any great conviction that they were responsive to, or could truthfully mediate, the protests, although both Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Melenchon tried to position themselves as the legitimate political expression of the occupations — that is, until protesters looted shops on the Champs-Élysées and attacked the Arc de Triomphe. Quite simply, it was difficult to understand the protests within the framework of the existing political system and its vocabulary. Sociological studies showed that many participants did not define themselves as significantly political, with roughly equal numbers voting for the Rassemblement National and what remains of the political Left in France. According to the sociologist Laurent Jeanpierre, the Yellow Vests broke the framework for understanding social movements in France by bypassing the institutions that have historically mediated and managed political protests.21 The roundabout occupiers rejected not only the Macron government but also “the usual practices of social mobilization.” They shunned the workers’ movement, occupied roundabouts in the countryside and semi-urban areas, and did not shy away from confronting the police and looting shops. Politicians and media were quick to condemn the looting and “wild” demonstrations and could not figure out how to initiate dialogue with the diverse crowd of protesters. The protesters were so heterogeneous that it was not possible for Macron, his ministers, local politicians or the various parts of the French public sector to engage the Yellow Vests in political dialogue. Macron eventually withdrew the tax increase, yet people continued to take to the streets. In this way, the roundabout occupiers not only challenged the political order but constituted, in the words of Jeanpierre, an “anti-movement.”22

In many ways, the Yellow Vests exemplify the new cycle of protest, much of which has taken place outside of traditional forms and channels of protest, alongside or in direct opposition to political parties and trade unions. It is more revolt than revolution, Di Cesare writes23; more anarchism than communism, according to Saul Newman.24 The demonstrators have been filled with anger, desperation and a hatred of the established political system. Marcello Tarì describes the many new protests as “destituent revolts,” referring to Benjamin’s notion of the Entsetzung of the general strike. As Tarì points out, protesters are not demanding anything from the political system; on the contrary, they are withdrawing their support, canceling, as it were, their participation in political democracy, in whatever form this takes, from Tunisia to France to Chile.25 As Tarì’s friends from the Invisible Committee put it in their report on the first wave of protests up to 2014: “They want to oblige us to govern. We won’t yield to that pressure.”26

The key contours of this new cycle of protests can be discerned as early as the start of the 2000s before, they really took hold at the turn of 2010–2011. In December 2001, hundreds of thousands of Argentines took to the streets to protest against the de la Rúa government’s austerity plans, banging on pans and pots and shouting, “Que se vayan todos!” (“They all have to go!”). The Argentinian economy was in free fall after more than a decade of corrupt privatization under the previous government’s economy minister Domingo Cavallo, who enjoyed strong backing from the IMF and was therefore able to govern across party lines. De la Rúa had been elected in 1999 on a platform of change, but soon reinstalled the ousted Cavallo, who continued to impose privatization and austerity. Unemployment rose, and poverty exploded, but there was no change in policy. At the end of December 2001, the uprising broke out. There were violent clashes, supermarkets were looted, and the police shot six demonstrators.

The Argentine activist collective Colectivo Situaciones, which itself took part in the fighting in Buenos Aires, subsequently described what happened in December as “a destituent uprising.” Demonstrators did not take a stand in favor of opposition politicians or other parts of the Argentinean political system, and refrained from demanding a softening of the IMF’s austerity plan, the possibility of withdrawing money, or anything else specific. Instead, they demanded a break with the political-economic system in general: “If we talk about insurrection, then, we do not do so in the same way in which we have talked about other insurrections [...]. The movement of 19th and 20th [of December] was more a destituent [destituyente] action than a classical instituent movement,” Colectivo Situaciones writes.27 Those who took to the streets at the end of December in Buenos Aires and other cities across Argentina rejected the government and refused not only to give their support to other politicians but also to unite as a political subject, i.e., as people who assert their power to overthrow the existing order and institute a new one.

Central to Colectivo Situaciones’ analysis was their identification of a shift away from the idea of establishing a counter- or “dual” power in the traditional Marxist sense. They argued that the demonstrators were not engaged in an attempt to overthrow the government or seize political power. They demanded not only the resignation of de la Rúa (which happened a few days later) but that all political representatives give up their mandates. The entire political system had to go. As Colectivo Situaciones describe it, a paradoxical political subjectivation took place in which the protesters did not become “the people” as a form of political sovereignty refusing to establish something new. “The revolt was violent. Not only did it topple a government and confront the repressive forces for hours. There was something more: It tore down the prevailing political representations without proposing others.”28 What was remarkable was the absence of a new constitution and the lack of any attempt to seize power.

If the seeds of the destituent insurgency model were sown in Argentina in 2001, it was in 2011 that they began to bloom. Colectivo Situaciones wrote insightfully about the complexities of describing the 2001 uprising, but the nature of it was ill-suited to the concepts Colectivo had adopted from Italian workerism and Latin American anti-imperialism. We see the same challenge echoed in the work of many commentators and analysts dealing with the new uprisings. A good example is the French philosopher Alain Badiou, who — in a series of books and articles from 2011 onwards — testifies to the great difficulty of analyzing the 2011 uprisings, the Arab revolts, the southern European square occupation movements and the Yellow Vests.29 According to Badiou, all of these movements lack an idea. They take to the streets to express discontent, but according to the veteran Maoist, they do not bring about change because they have no idea to which they are faithful. They are purely negative protests — and that’s a problem. Badiou wants the protesters to develop a strategy, a new communist project akin to those of Lenin, Stalin and Mao in their time. In doing so, he reveals his continued support for a state model of social happiness: the Yellow Vests and the other protest movements lack discipline and direction — in other words, organization. Badiou rebukes those who take to the streets, beating them over the head with handed-down notions of revolutionary practice. In doing so, he paradoxically ends up imprisoning the protesters in a historical deficiency: they are not a revolutionary movement precisely because they do not have a particular (historically compromised) idea (of socialism and communism).

Badiou’s pedantic analysis of the new cycle of protests is just one example of the difficulties many have when confronted with the new protests and their apparent lack of recognizable revolutionary or reformist slogans and political gestures. The late Zygmunt Bauman explained that protesters “are looking for new, more effective means of winning political influence, but [...] such methods have not been found yet.”30 With a mixture of condemnation and resignation, the English art historian and former Situationist T.J. Clark ironically criticized the young people who looted shops in London in 2011: they rejected commodity capitalism yet simultaneously affirmed it by stealing sneakers and iPhones.31 The conclusion seems to be that the protesters are trapped in a closed circuit of images and, as such, do not have access to a critical position from which to formulate a coherent critique of the current order. Badiou, Bauman and Clark all have a point, but their critique of the new movements has a patronizing air about it, and tends to dismiss the protests with a hurried comparative analysis of past revolutionary moments. Instead, we should perhaps, like Colectivo Situaciones, emphasize the element of experimentation and try to describe it. Doing so would enable us to anchor the new protests in a longer historical trajectory, in which an earlier vocabulary disappears as the economy changes, yet without blaming the new protests for not continuing or reactivating earlier forms of protest. The truth is that the political-economic conditions have changed, eroding the premises for the previous models that Badio and Clark long for. What is interesting is how the new movements attempt to formulate a critique in a situation of radical crisis and collapse.

The long crisis and the disappearance of the worker

The erosion of the historical vocabulary of protest must be rooted in a longer historical trajectory. This is precisely what the old left intellectuals have failed to do. This is a trajectory in which the Western workers’ movement in the post-World War II period tended to merge with political democracy. As another old communist thinker, the workerist Mario Tronti somewhat polemically put it, it was democracy, not capitalism, that killed the labor movement as a dissident alternative.32 As we know from another Italian philosopher, the Stalinist Domenico Losurdo, the bourgeoisie fought fiercely to avoid a socio-material transformation in which ownership of the means of production would become a political issue.33 Representative democracy became a way of ensuring that this question was never really formulated, or at least was formulated in a way that never called into question the capitalist mode of production’s logic of accumulation.

During the interwar period, the vision of a different society, beyond wage labor and the division of labor, slowly but surely began to evaporate from European social democratic parties and disappeared for good in the post-war consumer society. Labor-market reforms by socialist parties — exemplified by Gerhard Schröder’s Hartzen reforms in the 1990s — constituted the farcical phase of this development. If democracy was still a term for the rule of the poor in the 1840s, and Marx and Engels could therefore call themselves democrats, in the 20th century, the meaning of the term slowly transformed to mean majority rule and representation. This involved the implementation of various institutional processes aimed at ensuring that private property rights remained untouched so that the bourgeoisie not only maintained its economic power but extended it into the political dimension. As Lenin never tired of emphasizing, the bourgeoisie has a head start in democracy because it owns “9/10 of the best meeting halls, and 9/10 of the stocks of newsprint, printing presses, etc.”34 Therefore, he continues, in a heated debate in 1918 with German Social Democrats like Kautsky and Schneidemann, elections never take place “democratically.” The European Social Democrats did not follow Lenin’s advice but began to participate in the national democratic competition. They did so initially because they believed that democracy was the most favorable terrain for the overthrow of capitalism. As is well known, this did not turn out to be the case. This is why Tronti passes such a harsh judgment on national democracy, describing it as the bane of the workers’ movement. In retrospect, it is clear that political democracy transformed the workers’ movement from an external dissident force into an integral part of a political-economic system based on exploitation and accumulation. Admittedly, it was only after two world wars, a deep economic crisis and the emergence of fascism that political democracy managed to mediate the struggle between labor and capital, and the bourgeoisie began to feel confident about the working classes’ allegiance to various national communities. The conflict within the class-divided society was resolved with political rights, cheap commodities, and welfare.

A more positive account of this historical trajectory is found in the work of Michael Denning, who argues that the labor movement pressured the bourgeoisie to extend the franchise and establish what he calls “the democratic state.”35 Denning reads the establishment of this state form as a victory, but at the same time acknowledges that victory was short-lived and, in retrospect — i.e., after neoliberal globalization (Denning calls the period since the mid-1970s “the new enclosures,” citing the Midnight Notes collective) — appears hollow. The establishment of the welfare state, which Étienne Balibar calls “the social nation-state,” was a victory for the workers’ movement insofar as many more subjects (in the “First World,” i.e., Western Europe and the United States) were not only recognized as political subjects (as citizens), but also, to a large extent, gained access to steady jobs, education, culture and cheap, mass-produced goods.36 The democratic nation-state emancipated urban working families from the poverty brought about by the agrarian revolution and industrialisation. However, at the same time, it also led to the gradual neglect of the dream of a more radical supersession of capitalist society, its particular compulsions and its forms of alienation. Not only was the factory still hell for many women, young people, and migrants, but they were all still subject to patriarchal rule both at home and at work. Add to this the neo-colonial restructuring of the world economy after 1945, and the post-war welfare state appears considerably less admirable. Welfare and nationalization “at home” went hand in hand with neo-imperialism in the former colonies, exemplified by Clement Attlee’s “progressive” Labour government, which in the late 1940s and early 1950s nationalized the health service, transport, and much of the industry in Britain, yet imposed sanctions on Iran when newly elected Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddegh nationalized the country’s oil industry. Later, in collaboration with the US, Attlee’s government helped the Iranian military carry out a military coup to reinstate the Shah.37

The experimental ’60s were an attempt to reject gerontocratic power and challenge the rigid institutions of the welfare state in order to give everyday life an aesthetic boost. May 1968 can be read as an attempt to reactualize the vision of a different life as a social revolution — partly as a rediscovery of the revolutionary proletarian offensive of 1917–1921. However, these experiments still took place within the framework of the ideas of socio-material transformation to which the workers’ movement had formulated various responses throughout the 19th and 20th centuries with a view to replacing one (state) power with another.38 The New Left was precisely that — a new Left — or as Stuart Hall put it, the New Left worked both with and against Marxism in an attempt to develop it.39 For Hall and the New Left, Marxism (understood broadly as the workers’ movement’s reformist and revolutionary project of abolishing capitalism through a different kind of governance) was still the horizon. It was only with the movement of 1977 in Italy that a scathing critique of the Left truly emerged: “After Marx, April,” as the Metropolitan Indians wrote on the walls of Bologna in February of that year.

Marxism is no longer our horizon. This is what we see in the new protests, which take place beyond the theory of class struggle, the dictatorship of the proletariat and the proletariat as the subject of history, and without the huge institutional infrastructure that the workers’ movement built in the capitalist society. In a somewhat crude, materialist turn of phrase, industrialization enabled the workers’ movement to take up the struggle with the bourgeoisie, gain influence and participate in the management of national production. According to John Clegg and Aaron Benanav of Endnotes, “industrialization was to be the driver of workers’ incipient victory” since it brought growing numbers of industrial workers, growing unity among workers, and growing workers’ power in production.40 However, now that industrialisation appears to be over, the workers’ movement, in the various forms developed throughout the 20th century, is no longer able to organize opposition to exploitation and the dominance of capital. As the Italian Marxist Amadeo Bordiga and others have emphasized, capitalism is, first and foremost, a process of underdevelopment.41 In the post-war period, the picture was different. Focusing on developments in the West, you could almost be forgiven for thinking that capitalism was engaged in making material deprivation part of history. However, since the early 1970s, global capital has been undergoing one extended crisis — what left communist Loren Goldner calls “the long neoliberal crash-landing” — with falling productivity and growth rates that never reached the levels of the post-war boom.42 This is the context of the disappearance of the workers’ movement.

The French left-communist group Théorie communiste has described this transition as a departure from “programmatism.”43 From the mid-19th century until the end of the 20th century, revolution was a question of workers’ power. It consisted of workers affirming themselves as workers, whether through the dictatorship of the proletariat, soviets or various forms of self-government. The revolution was a program to be realized, one that would end with the proletariat coming into its own and overcoming the contradictions of class society. The worker was the positive element in this contradiction, the one who would realize the future society. Programatism, be it socialist reformism, Leninism, syndicalism or council communism, was based on a link between the accumulation of capital and the reproduction of the working class. The development of capitalist modes of production only strengthened the workers (although they also became increasingly exploited by intensified labor processes). However, according to Théorie communiste, this link no longer exists. The worker has disappeared and no longer constitutes a point of departure for collective, organized resistance. During World War II and the post-war period, the large apparatus established by the workers’ movement became part of the national social state and appeared less and less as an alternative to anything. Subsequently, as a result of the extensive reorganization of the economy that began in the mid-1970s, the identity of the worker was emptied of content — a development often termed neoliberalism, globalization or post-Fordism. In the old centers of capital, the reorganization took the form of de-industrialization, outsourcing, precarization, cuts in welfare programs, and a vast expansion of financial speculation, in which the production of value was detached from the direct production process.

In late capitalism, the worker is no longer an investment but merely an expense to be minimized. The Keynesian idea of a wage/productivity trade-off was replaced by the ever-increasing pursuit of lower costs. According to Théorie communiste, this shift constituted a counter-revolutionary response to proletarian resistance, and to May 1968 in particular. As they put it: “There is no restructuring of the capitalist mode of production without a defeat for the worker. This defeat was a defeat for the identity of the worker, the communist parties, trade unions, self-management, self-organization, and the rejection of work. It was a whole cycle of struggle that was defeated in all its aspects, the restructuring was essentially a counter-revolution.”44

However, as economists and historians such as Ernst Mandel and Robert Brenner have shown, this restructuring did not have the desired effect, and the world economy has been shrinking since the mid-1970s.45 The counter-revolutionary attack on the workers was insufficiently radical and therefore failed to establish a basis for a new class compromise. The bourgeoisie has destroyed more than it has built. This is the point of Goldner’s characterization of the last 40–50 years as one long unraveling or crisis, with rising unemployment, falling real wages, and cuts in social reproduction in the US and Western Europe. In many other parts of the world, the situation has been much worse. Local modernization processes in China and South-East Asia cannot hide this — and even there, the number of poor workers and peasants has increased exponentially.

This is the political-economic background to the erosion of the anti-capitalist language that characterized the revolutionary projects of the second half of the 19th century and the “short” 20th century, the “century of extremes,” as Eric Hobsbawm called the period from 1914 to 1989.46 In Marx’s terms, the working class and the proletariat begin to drift apart during the 1970s. Thus, when the new cycle of protest erupted in 2011, it did so in a historical void, “far from Reims” and displaced from the workers’ movement, from its forms of resistance, and from the identity of the worker.47

This is why most protests are not workplace protests but take the form of anti-political protests or looting. They are what Joshua Clover in a rather schematic historical analysis calls “circulation struggles,” in which protesters take what they can from shops and the “market.”48

Following Asef Bayat, who describes the Arab revolts as “revolutions without revolutionaries,” Endnotes has suggested describing the new protest movements as “non-movements” that produce “revolutionaries without a revolution.”49 Endnotes also enthusiastically describes how many of the protests of the past decade have emerged out of nothing. A Chilean high school student posts a call for a demonstration on Facebook, mobilizing tens of thousands of protesters. A police killing rapidly exploded in the most violent protests in recent US history since the late 1960s. A French lorry driver, street racing in his tuned car, calls for a protest against the Macron government’s new taxes and gathers more than 300,000 signatures in a matter of days. Each time, the protests seem to emerge far outside pre-existing parties and trade unions, which — at best — can only try to connect with these mobilizations or attempt to harness the energy they generate. However, even that is difficult. The fate of the various anti-political political parties, not least Podemos and Syriza, is testimony to this. As things stand, they are merely “weak social democracies.”50 Simply put, it is difficult to translate “non-movements” into state politics. The vast majority of participants do not belong to existing organizations but protest beyond the current political horizon. This is a “process” in the sense described by Verónica Gago in her analysis of the Ni Una Menos movement. It entails crossing a line from which there seems to be no possibility of returning to rejected political forms.51

Endnotes is, of course, affirmative with regard to the autonomy of protests. Following left communists such as Jacques Camatte, Endnotes writes that protests now seem to be characterized by an immanent dynamic by which they produce their own subjects. However, as the term “non-movement” indicates, this analysis is, as Kiersten Solt has argued, characterized by a certain melancholy: protests take place, but they lack form, they do not constitute a movement.52 The crisis of capital pushes people onto the streets, but since there is no longer an organized workers’ movement, nor any notion of workers as the proletariat, the protests are caught in an identity-political self-reflection, in which class struggle has become individual resistance, enacted together in the streets. The protests do not constitute a movement in the sense that both the established workers’ movement and the “other workers’ movement” did.53 Rather, they are first and foremost characterized by disintegration and fragmentation.

However, perhaps we should see the absence of the workers’ movement as a precondition for the new protests rather than a shortcoming.

Judith Butler attempts to do this in her analysis of the squatting movements, in which she discusses precarity as the condition of possibility for a new subject of resistance: “Precarity is the rubric that brings together women, queers, transgender people, the poor, the differently abled, and the stateless, but also religious and racial minorities.”54 Butler shows how the subject of the new protests must necessarily struggle for a commonality that transcends the individual case. However, she does not really explain how the particular and the universal are linked — through acts of will, or as a result of material processes? — and she, unfortunately, anchors her analysis within the framework of political representation and democracy. The point, however, is that there is no need to look back nostalgically, as Endnotes does in “Onward Barbarians” since the workers’ movement has usually historically prevented the proletariat from becoming the class-destroying class. Communism is “a defeat from within” — this was the lesson Walter Benjamin drew from the Kapp-Lüttwitz Putsch and the slaughter of the Ruhr uprising in 1920.55 Left communists like Camatte are no doubt very aware of that fact.

The aesthetics of rejection

If we are to supplement Endnotes’ more sociological and melancholic description of the new protests with a less defeatist, political-aesthetic terminology, we can go back to the late 1950s, when Maurice Blanchot, along with Dionys Mascolo and others, tried to think through the possibility of another, new form of resistance, outside of the workers’ movement, the state and politics in general. Throughout the history of the workers’ movement and the revolutionary tradition, there have been plenty of attempts to bypass the movement’s institutions, from wildcat strikes to DIY actions. However, this wild socialism — which in the case of Blanchot and Mascolo we might call literary communism — has usually been overshadowed by the established workers’ movement.56 We see this in Endnotes, which melancholically analyzes the shortcomings in the new protests against the background of the disappearance of the “worker.”

In two short texts from May 1958, Blanchot and Mascolo develop a notion of radical refusal in response to de Gaulle’s coup d’état in early summer that year.57 The old general had effectively used the Algerian liberation struggle, which appeared on the brink of spreading to France, to maneuver himself into position as president. The settlers and the French army in Algeria were in revolt and threatened to invade Paris if de Gaulle was not installed as head of government. The threat of an invasion prompted President René Coty not only to resign but also to plead with Parliament to allow de Gaulle to set up a temporary emergency government with extended powers.

The accelerated events of May–June 1958 led Blanchot and Mascolo to formulate a notion of radical refusal. Faced with this development, Mascolo — a former resistance fighter who had been expelled from the French Communist Party, an editor at Gallimard and a philosopher who wrote very little — in collaboration with the young surrealist Jean Schuster, launched the journal Le 14 Juillet to address the situation. To the first issue, Mascolo contributes a short text entitled “Unconditional Refusal,” in which he writes: “I cannot, I will never accept this.”58 For Mascolo, the refusal was directly linked not only to the soldiers who deserted the French army but also to the Algerian revolutionaries who refused to speak under interrogation: “To speak like that in reality, to say no, and to justify this refusal, is to refuse to speak — I mean refuse to speak to the interrogator, and if it is authorized to make that claim, under torture.”59 Mascolo could not have more forcefully problematized the anti-fascist consensus on which the post-war political opinion rested — and of which the French Communist Party was a part. France had to get out of Algeria. The Algerian revolutionaries had the right to rebel. Indeed, their struggle was not unlike the French resistance during World War II.

In his short text, Mascolo presented a perspective that made it important to speak out, effectively forcing the intellectual to take a stand, quickly and immediately, against society, in favor of another community founded on the rejection — or the impossibility — of accepting the events. “I cannot, I will never accept this. Non possumus. This impossibility, or this powerlessness, that is our very power.”60 It was necessary to refuse the political “solution” — de Gaulle back in power — even without putting something else in its place.

In the following issue of the journal, Blanchot contributed a short text entitled “The Refusal.” “At a certain moment, when faced with public events, we know that we must refuse. Refusal is absolute, categorical. It does not discuss or voice its reasons. This is how it remains silent and solitary, even when it affirms itself, as it should, in broad daylight.”61 Blanchot refused. He said no. A “firm, unwavering, strict” no. Blanchot not only rejected de Gaulle, but politics in general. It was what he later described as “a total critique,” directed against the techno-political order of politics and the state.62

The rejection was absolute. It did not invite negotiation. It did not propose anything. For those who rejected, there was no compromise. De Gaulle was the compromise. The threat of military occupation of Paris was part of the compromise that allowed de Gaulle to appear as a solution as if he came to power naturally. He was just there. Once again, he was the savior of France. In 1958 as in 1940. Blanchot rejected this entire process. The political game. Coty, Mitterrand, de Gaulle and the military. There was no need to explain his rejection. It was absolute.

Blanchot rejected de Gaulle and the false choice between civil war or the general — the civil war was already underway in Algeria and continued after de Gaulle came to power — but he also refused to formulate a political demand, a different path, a different solution. The refusal was “silent.” In this way, there was a difference between Blanchot’s refusal and other contemporary interventions (Roland Barthes, Socialisme ou Barbarie, the Situationists, etc.) that took the form of political analyses and mobilization. Blanchot did not mobilize. The rejection was, of course, a political intervention — or, at least, an intervention in politics. Previously, Blanchot had explicitly refrained from engaging in political debate.63 Now, he had returned to the fray. Or rather, he had not. The refusal was not an engagement with politics, but a cancellation of the political — and of the logic of representation that governs politics.64

The refusal did not give rise to a political community in any traditional sense. There was no identity, no nation, no republic, not even a working class, nor a program around which the community could unite. The rejection was anonymous. It did not present a program that could be placed alongside existing ones. It did not enter into a political discussion. Rather, it withdrew. As Blanchot put it, “the refusal is accomplished neither by us or in our name, but from a very poor beginning that belongs first of all to those who cannot speak.”65 The refusal was, therefore, a mute statement. It pointed to a gap in representation and did not refer to any recognizable political subject.

In these two short texts, Blanchot and Mascolo outline a different kind of movement, a movement that rejects, that breaks with the state but also with the notion of politics as a new constitution, a revision of the law, a new law or a new government. It is a strange kind of revolutionary movement that does not recognize itself in a program or a party, that does not have a list of members, that emerges offering no promises, without the possibility of joining it. In the early 1980s, Blanchot, in dialogue with Jean-Luc Nancy, called it “the unavowable community”, a community one cannot join or affirm as a political gesture. Refusal is an antagonistic gesture that abandons both telos and arché.

Of course, Blanchot and Mascolo’s refusal draws on, and is part of, the Euro-modernist avant-garde, and its contribution to the notion of a communist revolution. Avant-garde movements, from Dada and Surrealism to the Situationist International, expanded historical materialism’s notion of revolution, emphasizing that the socio-material transformation must necessarily be accompanied by a psychological reorganization. It was an understanding of the revolution as an open process, an experiment in which there is no plan to be followed nor a program to be realized. The revolutionary process is both material and metaphysical. It concerns man, society and nature. In retrospect, we can say that the avant-garde and experimental art formed an important, often overlooked part of the revolutionary tradition.

As Debord explained in The Society of the Spectacle, Dada and Surrealism were not only contemporaneous with, but part of, the revolutionary proletarian offensive in the years after 1917. Among other things, their contribution was to make it clear that the revolution is not simply a question of who has power, or how production is managed, but concerns the whole of human life.66 This is why the Surrealists sought to liberate le merveilleux (the marvelous) and entered into an impossible collaboration with the French Communist Party: “Rimbaud and Marx” side by side, as Breton proclaimed.67 Impossible because the Russian Revolution quickly went off the rails: the Bolsheviks seized power and did everything to keep it, including crushing the anarchist Mahkno and the striking sailors in Kronstadt, militarizing society, violently abolishing the peasantry, implementing an ecologically disastrous industrialization, and destroying one revolutionary venture after another through the Comintern and the national communist parties — the French one being exemplary. The Surrealists realized that the revolutionary venture could only take place outside the Communist Party by means of what the Situationists later, following the end of modernism, called the “art of war.” After World War II, COBRA, the Lettrist groups and the Situationists continued the anti-artistic and anti-political experiment, in which the “critique of everyday life” became an attempt to suppress art and politics as specialized activities in favor of satisfying humanity’s radical needs.

With Blanchot and Mascolo, we are dealing with a different idea of revolution, in which the revolution does not end with the establishment of a new regime.68 It is not about taking power but dissolving it. If it is a power, it is a power-dissolving power — “pouvoir sans pouvoir” (“power without power”), as Blanchot calls it.69 This idea of revolution cannot be formulated as a new constitution, it cannot manifest in the form of rights. It is the movement as a post-metaphysical community, without unity or program, in which all political subjects (the citizen, the worker, the avant-garde, the multitude) disintegrate. Revolution is not an aim to be realized but a truth to be inhabited here and now. This is what Tarì and the Invisible Committee call “destituent insurrection.”70

My proposal is to complement the many good analyses of the new cycle of protests (Tarì, the Invisible Committee, Juhl, Di Cesare, and Jeanpierre) with Blanchot and Mascolo’s attempts to inspire a movement of refusal. Doing so makes it possible to analyze the new cycle of protests without having to refer to the disappearing workers’ movement as a loss, as Endnotes tends to do. The new protests are occurring in the wake of programatism, but we do not need to hold up the different political forms and strategies of the workers’ movement as a prism through which to interpret what has taken place since 2011. In fact, as Solt argues in her “Seven Theses on Destitution,” this prevents an analysis of what is happening and reduces the revolution to a left-wing project.71 Instead, a different insurrectionary movement is now underway. Instead of thinking of the new cycle of protests as a non-movement, we need to understand it as a radically open movement. It is what Giorgio Agamben, in a lecture on movements, referring to St Paul, has spoken of as a hōs mē movement, an “as not” movement — that is, a movement that does not assert an identity.72

An important point in Blanchot’s and Mascolo’s sketches is the autonomy that they argue characterizes protests and revolts. As Carsten Juhl writes, when a protest becomes an uprising, it becomes its own substrate.73 It is immanent, that is, it builds itself, but without the prospect of redemption. It creates what the Situationists called “positive voids,” in which “everything that is done has a value in itself,” as Furio Jesi writes in his analysis of the Berlin uprising of 1919.74 Endnotes concurs in “Onward Barbarians,” emphasizing that something new happens on the streets when people suddenly come together and challenge power. In other words, protests have an autonomy — an autonomy that we risk losing when we necessarily think of dissident protest in terms of a continuum of existing (or absent) political organizations.

The new protests take place in the dissolution of previous isms — socialism, communism, anarchism, Leninism, Maoism, etc. This is what Badiou finds so difficult to understand. Even Endnotes finds it difficult to affirm this disappearance. The new protests are anonymous, and the first thing that disappears is the self. In an atomized, late-capitalist world characterized by rapid identity fixes, individuality is, of course, immediately reintroduced. Late fascism is one desperate expression of this, but so is the marketization of protest, black bloc versus non-violent demonstrators, etc. We, therefore, start with this: the uprising is a rejection of society and commodity-based individuality. It is a dissolution of the self as individuality and as a political standpoint, as a signature. Even if people take to the streets in accordance with their identity (politics), a shift occurs once the uprising gets off the ground. It is not as an individual, class, or mass that people take to the streets. Protests are radically unstable. They dispel the familiarity of late-capitalist life and dissolve all of the identities at our disposal. This is the “poor beginning” Blanchot described, the unarticulated refusal. In this sense, the movement that takes place is a disembarkation, the beginning of a more extensive escape. In it, no one is interested in becoming “civil society’s junior partner.”74 Rather, they are turning away from the community of capital, the money economy, the state and the workers’ movement — the last two being nothing more than “a fable for dupes.”75

October 2023

Images: Göksin Sipahioglu

Notes

1. Alain Bertho, Le temps des émeutes, Bayard, 2009.↰

2. Dilip Gaonkar, “Demos Noir: Riot after Riot”, Natasha Ginwala, Gal Kirn and Niloufar Tajeri (eds.), Nights of the Dispossessed: Riots Unbound, Columbia University Press, 2021, 31.↰

3. Cf. Beverly J. Silver and Corey R. Payne, “Crises of World Hegemony and the Speeding Up of History”, Piotr Dutkiewicz, Tom Casier and Jan Scholte (eds.), Hegemony and World Order, Routledge, 2020, 17-31.↰

4. Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There no Alternative?, Zero Books, 2010.↰

5. Cf. Robin Wright, “The Story of 2019: Protests in Every Corner of the Globe”, The New Yorker, 30 December 2019. Online here.↰

6. The Danish Bordigist Carsten Juhl uses the description “underground Bildung (education)” to describe the new protests and the latent revolutionary perspective observable within them. It might be difficult to see as one protest is repressed or dies out before the next one emerges in a different place, but Juhl’s idea is that they virtually constitute the coming-into-being of a ghost-like new proletariat. Carsten Juhl, Opstandens underlag, OVO Press, 2021, 35. In many places, lockdowns did interrupt revolts that were underway, and the anti-rebellion regime that was put in place during the 00s after 9/11 was taken one step further. The interruption did, however, not last long.↰

7. There is evidently no direct causal relation between economic crises and mass protests that turn into revolts or revolutions. In the inter-war period, a whole generation of Marxists had to come to terms with the fact that “politics” does not necessarily swing to the left when the “economy” does so. Protests cannot be reduced to “economic” or “sociological” facts that can then be understood as somehow indicating causality. Indeed, it is difficult to identify the “origin” of a protest. As Walter Benjamin explained in “On the Concept of History,” insurrections short-circuit both past and present, and suspend historical continuity. Following Benjamin, Adrian Wohlleben describes this process as one in which “potentially-political” or “ante-political” life forms are mobilized and put to use in protests. Adrian Wohlleben, “Memes without End,” Ill Will, May 17, 2021. Online here.↰

8. Deutsche Bank, “An Age of Disorder”, 2020, Deutsche Bank. Online here.↰

9. Censor, Truthful Report on the Last Chances to Save Capitalism in Italy [1975]. Online here.↰

10. George Hoare, Philip Cunliffe and Alex Hochuli, The End of the End of History: Politics in the Twenty-First Century, Zero Books, 2021, 73-76.↰

11. SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute), “Trends in World Military Expenditure, SIPRI Fact Sheet, April 2021”, 2022. Online here.↰

12. Anonymous, Conspiracist Manifesto, translated by Robert Hurley, Semiotexte, 2023, 353-354. ↰

13. Jacques Wajnsztejn and C. Gzavier, La tentation insurrectioniste, Acratie, 2012, 7. Disparagingly, because within left communism, describing something as an "’ism” is the same as describing it as a style or ideology. ↰

14. Slavoj Žižek, The Year of Dreaming Dangerously, Verso, 2012, 54↰

15. Fredric Jameson, The Seeds of Time, Columbia University Press, 1994, xii.↰

16. Donatella Di Cesare, The Time of Revolt, translated by David Broder, Polity, 2022, 8.↰

17. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Declaration, Argo Navis, 2013, 4.↰

18. Des révolutionnaires syriens et syriennes en exil, “Les peuples veulent la chute des régimes,” Lundi Matin, December 14, 2018. Online here. ↰

19. For a useful analysis of the spread of tactics, see S. Prasad: “Blood, Flowers and Pool Parties”, Ill Will, January 2, 2023. Online here.↰

20. Rodrigo Nunes, Neither Vertical nor Horizontal: A Theory of Political Organisation, Verso, 2021.↰

21. Laurent Jeanpierre, In Girum. Les leçons politiques des ronds-points, La Découverte, 2019, 19.↰

22. Jeanpierre, In girum, 19.↰

23. Di Cesare, The Time of Revolt, 10.↰

24. Saul Newman, Postanarchism, Polity, 2016, 49.↰

25. Marcello Tarì, There is no Unhappy Revolution: The Communism of Destitution, Translated by R. Braude, Common Notions, 2021.↰

26. The Invisible Committee, To Our Friends, Translated by R. Hurley, Semiotexte, 2014. Online here.↰

27. Colectivo Situaciones, 19 and 20: Notes for a New Social Protagonism, Minor Compositions, 2011, 52. Translation modified.↰

28. Colectivo Situaciones, 19 and 20, 26.↰

29. Alain Badiou, The Rebirth of History: Times of Riots and Uprisings, Verso, 2012; Greece and the Re-invention of Politics [2016]; “Lessons of the Yellow Vests Movement” [2021], Verso blog. Online here.↰

30. Zygmunt Bauman, “Far Away from Solid Modernity: Interview by Eliza Kania,” R/evolutions, vol. 1, no. 1, 2013, 28.↰

31. T.J. Clark, “Capitalism Without Images,” Kevin Coleman and Daniel James (eds.), Capitalism and the Camera: Essays on Photography and Extraction, Verso, 2021, 125.↰

32. Mario Tronti, “Towards a Critique of Political Democracy” [2007], Cosmos and History, vol. 5, no. 1, 2009, 74.↰

33. Domenico Losurdo, Liberalism: A Counter-History, Translated by Gregory Elliott, Verso, 2014.↰

34. Lenin, “‘Democracy’ and Dictatorship” (1918). Online here.↰

35. Michael Denning, “Neither Capitalist, Nor American: Democracy as Social Movement,” Culture in the Age of Three Worlds, Verso, 2004, 209-226.↰

36. Etienne Balibar, We, the People of Europe? Reflections on Transnational Citizenship, Princeton University Press, 2004, 61.↰

37. Cf. Kojo Koram, Uncommon Wealth: Britain and the Aftermath of Empire, John Murray, 2022.↰

38. This was exemplary in the case of most Western Maoists of the period, who remained attached to a notion of power and a power alternative. The Situationists made progress in dissolving the idea of another form of power. They were critical of Socialists, Leninist and Maoists, but as was the case with the May ’68 movement in general, they upheld an idea of another way of running production. In the case of the Situationists, this was to be done via councils.↰

39. Stuart Hall, “Cultural Studies and its Theoretical Legacies”, Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson and Paula Treichler (eds.), Cultural Studies, Routledge, 1992, 279.↰

40. John Clegg and Aaron Benanav, “Crisis and Immiseration: Critical Theory Today”, in: Werner Bonefeld et al. (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Sage, 2018, 1636.↰

41. Amadeo Bordiga, Strutture economica e sociale della Russia d’oggi, Edizioni il programma communista, 1976.↰

42. Loren Goldner, “The Historical Moment That Produced Us: Global Revolution or Recomposition of Capital”, Insurgent Notes, no. 1, 2010. Online here.↰

43. Théorie communiste, “Prolétariat et capital. Une trop brève idylle?”, Théorie communiste, no. 19, 2004, 5-60.↰

44. Théorie communiste, “Prolétariat et capital,” 51.↰

45. Robert Brenner, The Economics of Global Turbulence: The Advanced Capitalist Economies from Long Boom to Long Downturn, 1945–2005, Verso, 2006; Ernst Mandel, Late Capitalism, New Left Books, 1975.↰

46. Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, Michael Joseph, 1994.↰

47. “Far from Reims” refers to Didier Eribon’s book Retour à Reims, in which Eribon, now a Paris-based professor of philosophy, returns to Reims, where he grew up. He describes how his working-class family have become supporters of Front National (Rassemblement National). Eribon’s story takes on the form of a melancholic analysis of this shift, in which workers who used to vote for the French Communist Party have ended up supporting Le Pen. However, this shift can also be seen as a form of continuity, because from 1944 onwards, the PCF did its best to support the notion of the nation — and in May ’68 not only distanced itself from, but critiqued the revolt, and did its best to discredit it (including engaging in the antisemitic slandering of Daniel Cohn-Bendit). ↰

48. Joshua Clover, Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings, Verso, 2016, 28.↰

49. Asef Bayat, Revolution without Revolutionaries: Making Sense of the Arab Spring, Stanford University Press, 2017; Endnotes, “Onward Barbarians,” Endnotes, 2021. Online here. Comparing the 2011 revolution to the Iranian Revolution, Bayat writes: “I find the speed, spread, and intensity of the recent revolutions extraordinarily unparalleled, while their lack of ideology, lax coordination, and absence of any galvanizing leadership and intellectual precepts have almost no precedent. […] Indeed, it remains a question if what emerged during the Arab Spring were in fact revolutions in the sense of their twentieth-century counterparts.” Bayat, Revolution without Revolutionaries, 2.↰

50. Susan Watkins, “Oppositions”, New Left Review, no. 98, 2016, 27.↰

51. Veronica Gago, Feminist International, Verso, 2020, 12.↰

52. Kiersten Solt, “Seven Theses on Destitution (After Endnotes), lll Will, February 12, 2021. Online here.↰

53. Cf. Karl Heinz Roth, Die ‘andere’ Arbeiterbewegung und die Entwicklung der kapitalistischen Repression von 1880 bis zur Gegenwart: Ein Beitrag zum Neuverständnis der Klassengeschichte in Deutschland, Trikont, 1974.↰

54. Judith Butler, Notes Towards a Performative Theory of Assembly, Harvard University Press, 2015, 58. For an extended commentary on this text, see Mikkel Bolt-Rasmussen, “Violence and Other Non-Political Actions in the New Cycle of Revolt,” Mute Magazine, April 4, 2021. Online here.↰

55. From his “Critique of Violence” in 1921 to “On the Concept of History” in 1940, Benjamin stressed that the workers’ movement was opposed to the revolution, and that, as Bini Adamczak writes, communism constitutes a kind of “inner defeat.” Cf. Bini Adamczak, Gestern Morgen. Über die Einsamkeit kommunistischer Gespenster und die Rekonstruktion der Zukunft, Assemblage, 2011.↰

56. In other words, communism not as a political identity authors should affirm, but as a particular mode of communion or being-together in the reading of literature.↰

57. For a presentation of the texts, see Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, “An Affirmation That is Entirely Other,” South Atlantic Quarterly (122:1), 19-31. For a detailed (albeit pro-de Gaulle) account of the events, see Odile Rudelle, Mai 58. De Gaulle et la République, Plon, 1988.↰

58. Dionys Mascolo, “Refus inconditionnel,” La révolution par l’amitié, La fabrique, 2022, 28.↰

59. Mascolo, “Refus inconditionnel,” 29.↰

60. Mascolo, “Refus inconditionnel,” 28. Non possumus is Latin for ‘We cannot.’↰

61. Maurice Blanchot: “Refusal” in Political Writings, 1953-1993, Fordham University Press, 2010, 7. ↰

62. Maurice Blanchot: “[Blanchot to Jean-Paul Sartre]” (1960), in Political Writings, 37.↰

63. As is well known, in the 1930s Blanchot was part of the French Far Right, writing a series of explicitly nationalist articles in different journals, including Combat. In 1940, he abandoned these links and refrained from participating in any kind of public political discussion. When he returned in 1958, it was, in the words of Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, as “a kind of communist.” Lacoue-Labarthe describes Blanchot’s movement from French fascism to “a kind of communism” as a “conversion.” Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, Agonie terminée, agonie interminable. Sur Maurice Blanchot (Paris: Galilée, 2011), 16. ↰

64. At this moment, Blanchot was also using the notion of refusal in his analyses of contemporary literature. In 1959, he published a text on Yves Bonnefoy, titled “The Great Refusal,”, in which he discussed how the poet broke with a Hegelian dialectics that makes subject and object identical, and argued that poetry is a “relation with the obscure and unknown.” Maurice Blanchot, “The Great Refusal,” in The Infinite Conversation, University of Minnesota Press, 1993, 47.↰

65. Maurice Blanchot, “Refusal,” 7.↰

66. Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, Zone Books, 1995, 136.↰

67. André Breton phrased it thus in the presentation he was not allowed to give at the International Congress of Writers in Defense of Culture. ↰

68. Perry Anderson defines revolution as: “The political overthrow from below of one state order, and its replacement by another. [..] A revolution is an episode of convulsive political transformation, compressed in time and concentrated in target, that has a determinate beginning—when the old state apparatus is still intact—and a finite end, when that apparatus is decisively broken and a new one erected in its stead.” It is precisely such an understanding of revolution Blanchot and Mascolo are trying to move beyond. Perry Anderson, “Modernity and Revolution”, New Left Review, no. 144, 1984, 112.↰

69. Maurice Blanchot, “Literature and the Right to Death” (1949), in The Work of Fire, Stanford University Press, 1995, 331.↰

70. Marcello Tarì, There is no Unhappy Revolution; The Invisible Committee, Now, Translated by R. Hurley, Semiotexte, 2017. See also the articles in the special issue of South Atlantic Quarterly edited by Kieran Aarons and Idris Robinson, entitled “Destituent Power” (Vol. 122, Issue 1), 2023.↰

71. Solt, “Seven Theses on Destitution.”↰

72. The movement has to remain open, always coming. In his 2005 lecture “Movement,” Agamben objects to a Schmittian understanding of movements as the political medium in which the people take on a political form. The task is to conceive of a movement that does not split the people in two: bios and zoe. Agamben does not refer to Paul in his lecture, but Paul’s understanding of the call is evidently the model for a different understanding of a movement that is not a movement. See Giorgio Agamben, “On Movements,” online here.↰

73. Carsten Juhl, Opstandens underlag, 11.↰

74. Raoul Vaneigem and Attila Kotányi, “Basic Program of the Bureau of Unitary Urbanism” [1961], cddc (online here); Furio Jesi, Spartakus: The Symbology of Revolt, Translated by A. Toscano, Seagull, 2014, 46. Online here.↰

75. “Civil society’s junior partner” is Frank B. Wilderson’s term for movements that do not question anti-Black violence in the attempt to oppose present powers. Frank B. Wilderson III, “The Prison Slave as Hegemony’s (Silent) Scandal”, 2003,” Social Justice, vol. 30, no. 2, 2003, 18-27. Online here.↰

76. The Invisible Committee, Now, 72.↰