The Production of the Dominant Dialogy

Grégoire Chamayou

The following is an excerpt from Grégoire Chamayou’s The Ungovernable Society. A Genealogy of Authoritarian Liberalism, appearing with Polity Press this spring.

Business itself, since it is engaged in a competitive struggle, is at war. —Arthur Fürer, Managing Director of Nestlé Group

Corporate Counter-Activism

Throughout the 1970s, employers’ calls for a counter-offensive continued. There was the same martial tone, the same threadbare military metaphors, the same spitefulness. In 1979, Donald Kirchhof, CEO of Castle & Cooke, maintained that what was taking place was a "direct assault on our economic system. [..] We are at war, but it is a guerrilla war [...] Let’s revitalize our corporate leadership and take the offensive, in the best tradition of American capitalism."

Business, they kept on repeating, was war. Capitalist enterprise is an institution that is continuously sparking upheavals, so it is vital for its leaders to learn to manage the conflict. Producing such conflict is part of its DNA, not only internally, with its own employees, but also externally, with the "social environment" that its operations impact on.

Faced with the challenge, new forms of know-how develop. There is a shift from a warlike rhetoric to a real strategic rethink. At the overlap between public relations, military intelligence and counter- insurgency tactics, something new was developing in this decade: the elements of a counter-activist doctrine of business.

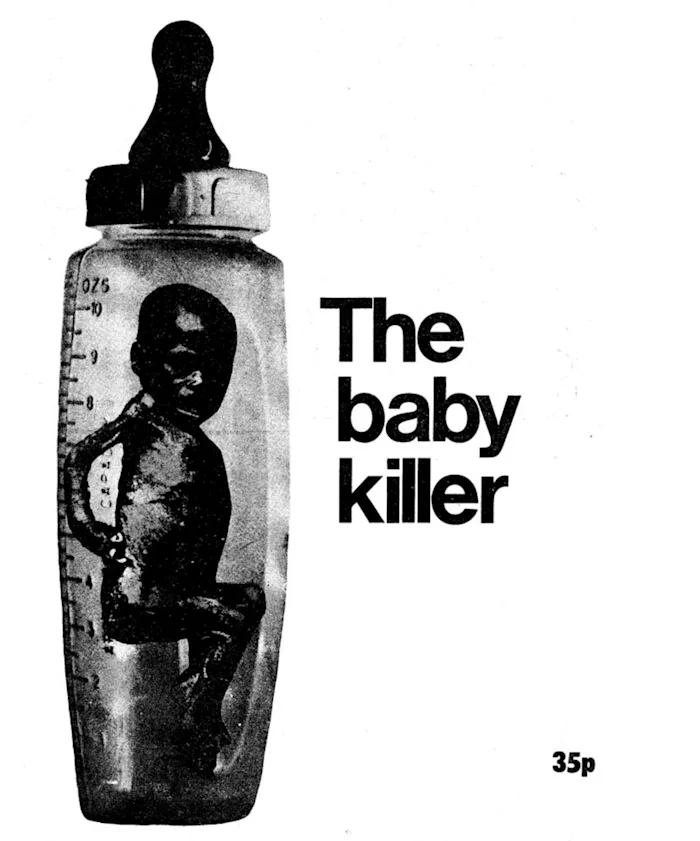

In 1974, British activists published a booklet called The Baby Killer. They denounced the health effects of the breast milk substitute marketed by Nestlé in Third World countries. Sold to populations that could often not read the instructions for use and that lacked access to drinking water, powdered milk was all too often toxic for infants. Ignoring the alerts issued by nutritionists, Nestlé conducted marketing campaigns that involved, for example, getting female representatives of the company to distribute samples; dressed in nurses’ suits, they deterred African mothers from breastfeeding.

This militant text might have remained confidential if the company’s managers had not made the mistake of overreacting. In 1974, this behemoth of agribusiness sued a Swiss group that had translated the brochure into German, thus giving a global resonance to the accusations in it. In July 1977, American activists called for a boycott of Nestlé. Four years later, more than seven hundred organizations had joined their cause worldwide.

This was one of the first boycott campaigns to be launched on such a scale. Faced with a multinational, on issues of life and death, the struggle was internationalized; consumers in the North were encouraged to act in the face of corporate actions carried out in the South. In this fight, says Bryan Knapp, "biopolitics converged with geopolitics [...] within what we might call bio-capitalism."

Nestlé managers were initially completely taken aback by a movement they did not understand. In November 1980, a Swiss executive from Nestlé landed in Washington. "Relying on what was generally being said in Vevey [at the firm’s headquarters], he was sure that the boycott involved only a tiny minority of over-excited protesters. No sooner had he landed than he spotted a bumper sticker on a car saying 'Boycott Nestlé.' He was shocked, and exclaimed: 'Ah! the bastards, the bastards!'"

Business leaders became aware of a hitherto unsuspected vulnerability. To their bitter surprise, small networks of activists could, despite the radical asymmetry in their material means, exert considerable pressure on big industrial groups. This was just the beginning: "the activist movement is approaching internationalization [...] In the future, there may be other concerted attacks against multinationals by united activist groups."

The costs of the boycott were soon felt, "not only through the hours that Nestlé bosses were forced to waste addressing it, but also because of the dejection into which it sometimes plunged them and their subordinates. It was mostly 'psychologically, emotionally,' that it affected the corporation." Nestlé "had even approached a psychoanalyst to deal with the despondency into which the controversy plunged the staff."

With its back against the wall, the firm decided to change approach. It recruited a special advisor who had already started to make a reputation for his expertise in crisis management: Rafael Pagan, a man of the hard right and a former military intelligence officer. He had been an advisor on these issues to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, and in the late 1970s became a business advisor. He joined Nestlé in January 1981 to set up a task force to fight the activists for every inch of the ground.

Members of this team, composed in part of former military men, would later be found sitting on the board of Pagan International in the mid-1980s, then at Mongoven, Duchin & Biscoe, and finally, in the 2000s, at "Stratfor." If the name of this outfit rings a bell, this may be because the hacker Jeremy Hammond exposed it in 2011, posting thousands of electronic messages that he had hacked from its servers on WikiLeaks. In the meantime, for three decades, these experts in counter-activism had been selling their services at a high price to multinationals that were about as commendable as Shell in the face of the anti-apartheid boycott, or Union Carbide, or Monsanto.

Management traditionally had two major ways of thinking about antagonism: social conflict within business and competition in the market. Internal tension with subordinates, external competition with rivals. With the eruption of an activism targeting multinationals, a third case, strange and unexpected, was now presenting itself: an external social conflict, against which traditional tactics proved inadequate. Firms which had first thought they could treat this new challenge in the same way as labour disputes eventually realized that "these new stakeholders also do not want to be managed within the corporate defined operational parameters." If those external forces over which they no longer had any hold were to be fought off, they had to adapt, by developing a completely different repertoire of countermeasures.

If the "anti-business activists" managed to keep multinationals in check, thought Rafael Pagan at the time, this was not because they were "smarter than the men and women of Nestlé," but because they, at least, "know they are in political combat, while business people – even today – do not." Business management might well be able to draw on colossal resources, but until they actively organized for political struggle, they would suffer setbacks: "I don’t think we will ever be loved or popular [...]. But we can, if we learn to think and act politically, defeat our activist critics." It was time for corporations, added his colleague Arion Pattakos, to "meet activism with activism."

In October 1985, after the boycott had ended, one of the main organizers of the campaign against Nestlé, Douglas Johnson, met one of his old opponents, Jack Mongoven, Pagan’s right arm, in São Paulo. They dined together, drank wine and spun the conversation out into the small hours. Johnson wrote a report on this interview, today preserved in the archives of the Minnesota Historical Society in Saint Paul.

This may sound self-serving, but Ray and I were the strategists. We are very different; I come out of political campaigns, and he out of the army [...] The very first day, we were filling up the room with analysis, Ray left the room, and I just wrote up on the wall the nine principles of Clausewitz. I had studied him in college, and found him always useful in developing political campaigns. [...] Ray came into the room, looked at me and asked if I had gone to the War College; I said no, I’d never been in the Army. And he said, but you know those are the principles of Clausewitz. That’s part of how we discovered how well we could work together and complement one another. Sun Tzu’s work was very important to how we developed our campaign. The difference for you was in the early years, while you all developed strategy, you were up against people in Switzerland who had no idea of strategy, and never developed one.

"It was like planning for a major combat mission," he still remembers. "We looked at all of the important conditions: our strengths and vulnerabilities, your strengths and weaknesses, including your base of support." This was an application to the activist question of the "SWOT" model (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats), a market analysis method based on the cross-examination of the strengths and weaknesses of the organization and its rivals, as well as the opportunities and threats in the environment. The anti-activist know-how that was pieced together in this way borrowed from several sources: the hybridization of military strategy, party strategy and market strategy.

As Mongoven said to the activist Douglas Johnson, "your weakness was resources, your strength was lots of committed people. Our strength was resources; our weakness was people. So we had to design tactics to upset your strengths. A lot of time we adopted tactics, not because they directly helped our strategy, but because they could disperse your efforts."

How is it that small, poorly funded militant groups, overworked and always on the verge of burnout, could represent a menace for economic empires with incomparable resources? The answer of these analysts was that their trump card, with its many knock-on effects, lay in their "ability to mobilize legitimacy" — something that the firms on the other side cruelly lacked. "Your legitimacy, and your strength, came from others: from the churches, from the teachers, from a small group of scientists, from some health organizations. What we did was identify targets and develop tactics to deprive you of their support or legitimacy, so then we could deal with you on our terms." This meant breaching the adversary’s defences so as to deprive him one by one of his "blocks of credibility."

Throughout the many campaigns they conducted, Pagan and his colleagues developed a typology of activists. This simplistic scheme allowed them, at each new confrontation, to place their opponents in small stereotypical psycho-tactical boxes. Another member of the gang, Ronald Duchin, set out this house typology one day at a congress of the American Association of cattle farmers, and his intervention was then printed in the organization’s bulletin: "I am also a cattleman," he began as a captatio benevolentiae. "My wife and I run a good-sized Limousin and Charolais cow and calf operation in the Kentucky Bluegrass [...] one way or another we all are activists. However, the activists we are concerned about here are the ones who want to change the way your industry does business." Take the case of the BST growth hormone (bovine somatotropin) produced by Monsanto: "Most of you know it very well. So do I because we work for Monsanto on the issue [...] BST is a synthetic hormone produced by biotechnology. It has been shown to increase milk production in dairy cows by 10 to 25 percent. Yet it is under attack by a plethora of public interest groups."

But who are these groups? If you want to defeat them, you need to know them. But this is not complicated: they fall, invariably, into four main categories:

The radicals. These want to change the system, they have underlying socio-economic/political motives, are hostile to enterprise as such, and may be extremist or violent. With them, there is nothing to be done.

The opportunists. These offer visibility, power, followers and, perhaps, even employment. The key to dealing with opportunists is to provide them with at least the perception of a partial victory.

The idealists. These people are usually naive and altruistic. They apply an ethical and moral standard. The problem with them is that they are sincere, and, as a result, very credible. Except they are also very credulous. If it can be shown that their opposition to an industry or its products causes harm to others and cannot be ethically justified, they are forced to change their position.

The realists. These are a godsend. They can live with trade-offs; they are willing to work within the system and want to work within the system. They are not interested in radical change, but are pragmatic.

Faced with protest, the way forward is always the same: to negotiate with the realists, knowing that in most issues, it is the solution agreed upon by the realists which is accepted, especially when business participates in the decision-making process. Also, the idealists need to be re-educated into realists — an educational process, according to Duchin, which requires great sensitivity and understanding from the educator. If you can manage to work with the realists and re-educate the idealists, they will switch over to your position. Once these critics of conscience have been turned, the radicals will lose the broad credibility that the support of these moral authorities had conferred on them. Without support from the realists and the idealists the positions of radicals and opportunists are seen to be shallow and self-serving. At this point you will always be able to count on the opportunists to accept the final compromise. The premise is that the "radicals" derive their strength only by drawing closer to more moderate blocks. Without this link, they are negligible. Radicals isolated in their niche of radicalism are harmless, and pose no threat: a bit of minority folklore without any impact. Such, then, is the general strategy: to cooperate with the realists, to converse with the idealists so as to convert them into realists, to isolate the radicals and to gobble up the opportunists.

In Nestlé’s boycott, the activists’ medium-term goal was to impose a "code of conduct" on firms in the sector. Rather than rejecting this prospect, Pagan made it his own and engaged in endless negotiations on the terms of the code. It was a matter of formally embracing the principle so as to better sabotage the content. Faced with what he decided was an ethical critique of multinationals, Pagan believed that rejecting the lexicon of social responsibility was no longer a viable strategy: "The choice for industry is no longer whether it will be 'responsible,' but how. Are we going to act according to our own or to a negotiated agenda, or are we going to be dictated to?"

This tactic of acquiescence had the advantage of giving new luster to the firm’s brand, a veneer of credibility, while plunging protesters into tedious talks. This meant forcing activists to engage in long palavers. Shifting "the debate into the field of interpretations had been a deliberate strategy": busying the opposing leaders with matters other than boycotting Nestlé, and exhausting them in endless meetings — all this in order to divert the movement from the vital task of building up a deeply-rooted protest. This was a new tactic, based on dialogue.

The production of the dominant dialogy

At the same time, Socrates, our use of rhetoric should be like our use of any other sort of exercise. —Plato

It is not part of the official CSR ("corporate social responsibility") story as it is taught in business schools, but one of the first publications on the theme of the "social responsibilities of management" was sponsored, in 1950, by the great theorist of "public relations," Edward Bernays, the author of the famous work Propaganda.

A few decades later, however, his heirs saw that the public had learned to be wary of "defensive advertising" and forms of communication inherited from "partisan propaganda." Taking note of the wear and tear that the old formulae had sustained, the "mad men" made their self-criticism: "the Bernays paradigm defined the public relations role [...] as the 'engineering of consent' among a malleable public. [...] Translated into unscrupulous communication practices, such a paradigm now looks both ethically untenable and ineffective, as the public has learned to receive this type of PR effort with suspicion." The old propaganda no longer worked as well as before, and something else was needed. Advertising, of course, would not disappear, but an effort would be made to add other, subtler ways of bamboozling people.

The goal was to regain control of an order of expression that was out of control. But what would be the alternative, or rather the necessary complement to the old model? The new keyword was dialogue. New "public relations dialogues" praised "dialogic communication as a theoretical framework to guide relationship building between organizations and publics." Instead of propaganda, they recommended participation; instead of the vertical, the horizontal; instead of the unilateral, the reciprocal; instead of the symmetric, the asymmetrical. In the early 1980s, managerial ideologues, adopting a philosophical pose, sang the praises of dialogic reason, "ethical" in essence. And Habermas came along at just the right time — his "distinction between monological and dialogical rationality" fitted in nicely with this new approach. In this model, transmitter and receiver swap places to become, in a beautiful communicative symmetry, "equal participants in a communication process that seeks mutual understanding." Now the time of "ethical communication" had come, of "communication" as "conversation" or "neutral dialogue" as "a precondition of legitimacy in any corporate initiative." The time of overarching truths was over, promised these devotees of communication, these new converts to a respectable postmodernism: intersubjective agreement must now be co-constructed through a dialogue between stakeholders.

According to one management manual: "Philosophers have agreed that dialogue can enhance the ethics of communication because it reinforces the dignity and respect of both parties. [...] The philosophical notion of dialogos can be traced to Plato’s rejection of sophism as mere rhetoric, in which monologue was the style." Plato contrasted "sophism," we learned from our business philosophers (who got themselves into something of a tangle in the process) with the "dialogue where participants treated each other as means rather than ends [sic], and did not engage in a war of words." Philosophers are always good for soundbites. Still, you need to take the trouble (or pleasure) of actually reading them before quoting them, which might perhaps stop you mixing everything up (sophism and sophistry, Plato and Kant, means and ends, etc.). Not to mention that the said philosophers were far from being as angelic as people would like us to believe when it came to the practice of dialogue — starting with that pugnacious, corrosive, implacable dialoguer Socrates, who harried his opponent mercilessly.

Anyway, the contrast was seized on: there was monologue, an old idol that communicators now seemed to be trampling in the dust, with all its manipulation, pretense, dogmatism, insincerity and mistrust; and, on the other side, there was dialogue, with its concern for others, authenticity, open-mindedness, frankness, and trust. Instead of one-way persuasion, that detestable practice of the past, people now preferred reciprocal listening, mutual understanding, relational, empathetic communication based on consensus, the "co-creation of a shared understanding" between "stakeholders," horizontality, "recognition," the relationship to the other, and so on, ad nauseam. "Enough! Enough! I can’t bear it any longer. Bad air! Bad air! This workshop where ideals are fabricated — it seems to me just to stink of lies."

Except that there are two sides to the coin of these celebrations of dialogue, not one. Heads is ethics; tails is strategy. For a full view of the situation, we need to set the ethico-philosophical gloop against its double, namely the strategy of dialogue theorized at the same time by the experts of corporate counter-activism. Some quote Habermas, while others refer to Clausewitz, but it makes no difference: both — the philosophical version and the secret agent version — are the complementary faces of the same set of practices.

During their counter-campaign in the service of Nestlé, Pagan and his colleagues were convinced that "the resolution of the boycott would come about through long-term dialogue and one-on-one discussions with the critics." "For them, the dialogue was not a way to open up to others, it was a strategy, [...] another way of conducting the fight." On their side there was no dialogue, no willingness to negotiate: the discussion was aimed only at convincing "sensible" people that the firm was sincere and making them withdraw from the campaign. The purpose of this kind of discussion was not to "exchange" ideas but "to convince people of your point of view and motivate them to act for you."

Whereas traditional public relations sought to drown their opponents’ discourse under a torrent of justificatory advertising, this new tactic was based on the observation that "destruction of the adversary simply isn’t possible in an age in which anti-establishment dissidents command at least as much and sometimes more public attention and support than the corporations they attack." So you have to play your cards more carefully. "When an emerging issue threatens to become critical, the issue manager doesn’t instinctively 'put up his dukes' to fight the invader [...] Rather, he or she reaches out to leadership of adversarial groups and philosophies to explore rationally with them the possibility that they have interests in common which can be eliminated from the adversarial agenda."

Updating the theory of the production of the dominant ideology would these days involve a critique of the dominant dialogy. What are the virtues of dialogue as a strategy of power? We have already begun to glimpse some of them. Let us complete the inventory here.

1) The function of intelligence. Dialoguing with opponents makes it possible to identify the perils that crop up as soon as possible, to identify "potentially controversial issues before they reach the public arena." It is essential to find out what the opponent has in mind, not only to learn what his plans are, but to understand how he thinks.

Keep your friends close to you, but your enemies even closer — good fatherly advice. Try to establish channels of communication with the enemy’s groups, including those that "may even seem destructive — at least in the short run."

2) A function of confinement. Without his actually being asked for anything, one Nestlé executive in the early 1980s wrote a set of rules of conduct for activists, including this: "Contacting the targeted corporation and attempting to establish a dialogue [...] before mounting a public media campaign." The main advantage of this tactic of "non-governmental, intergroup resolution of emerging policy issues" was of a topographic order: relocating confrontation in a private forum, confining it far away from "public space." In doing so, activists were deprived of their main resource, namely the publicizing of the problems; their leaders were also freed from the social constraints which generally prevented them from overly compromising themselves in broad daylight. In circumstances where "leaders [...] are not too eager for the people to take the upper hand," wrote Montesquieu, "those who have wisdom and authority intervene."

3) A function of diversion. Chuck opponents a bone to gnaw on so as to divert them from offensive tasks. When, in the late 1980s, Pagan tried to break the boycott against South Africa, he stressed this point: "A key aspect of this strategy is to ensure that the Shell companies can counter that unbalanced situation by establishing their own meaningful dialogue with these crucial church groups so that churches perceive their anti-apartheid options in a more positive, creative sense than simply joining the Shell U.S. boycott." It was all quite clear: "To engage the ecumenical institution, churches and critical spokespersons in post-apartheid planning should deflect their attention away from boycott and disinvestment efforts."

4) A function of co-optation. But dialogue, if properly conducted, means above all that you can co-opt certain of the opponents’ "pressure groups." In "the classic corporate co-optation strategy," writes Bart Mongoven, corporations "seek out the loudest organization that can be identified as realistic. They sit down and offer the power, glory, and money of solving the problem to the loud realist. When the loud realist accepts, it convinces the public that the larger issue is resolved. The entire activist movement, therefore, get swallowed up (mostly involuntarily) by the single deal. Anyone who says the issue isn’t resolved looks radical or lacking credibility."

Activists often have an exaggerated picture of their opponents, say our experts; thus, it is not difficult to surprise them by presenting them with a completely different face from the one they expect.

Adopt a humble, open, listening attitude. Coax them by speaking their language, flatter them by treating them as a responsible organization, grant them recognition, dangle before them the image of a "constructive" action poles apart from "negative" or "sterile" opposition. Among the psychological manipulation techniques that Pagan advocates in order to turn the moderate detractors, there is this one: transmit to them sensitive documents that could harm — but not too much — the company if they were divulged, making them promise to keep them to themselves. In his experience, he says, such a pledge of confidence "was never betrayed."

5) A function of discrediting. One important point: these dialogues, thought to be a way of lobbying opponents, are selective. At the same time as they are working to include some groups, they also attempt to exclude others. Stressing "consensus" as the goal of "dialogue," the point is to discredit any dissensual policy, implicitly labelling "groups who do not engage in consensus-oriented direct discussions with industry as 'confrontational,' 'incapable of dialogue' and ultimately as 'unworthy' of participating in democratic decision-making processes." This means drawing a line of demarcation between those who are willing to dialogue and the rest — making some your satellites and discrediting others. They can be repressed all the more easily when they have been presented as being outside the logos.

6) A function of legitimation. By dialoguing with NGOs that enjoy a great aura of respectability, firms additionally benefit from "image transfers." Big companies relatively devoid of reputational capital can hope to acquire this from their detractors, especially as the latter are in a completely different position, one which favors synergies: low economic capital but a high degree of the power to bestow symbolic approval. On the basis of this asymmetry, relations of cross-co-optation can be created. From dialogue, people will move onto collaboration and partnership, the objective being to form coalitions under corporate dominance.

Thus "new corporate strategies to deal with turbulence created by critics" are developed. Over and above the reactive maneuvers aimed at the immediate management of overt crises, it will increasingly be a matter of anticipating, of developing a "systematic and proactive approach to criticism."

Excerpted from Grégoire Chamayou, The Ungovernable Society. A Genealogy of Authoritarian Neoliberalism, translated by Andrew Brown.

Footnotes and references have been omitted from this online edition, but can be found in the print version.