The Shifting Ground:

a Conversation on the George Floyd Rebellion

Jarrod Shanahan and Zhandarka Kurti

The murder of George Floyd catalyzed explosive social unrest of the sort not seen in this country in generations. Although things seemed to wane at a nationwide level by late June, the month of August saw a rapid resurgence of conflict, with mass looting taking place in Chicago, fierce clashes in several cities including Portland and Richmond, and a major revolt in the city of Kenosha, WI lasting three days and culminating in clashes and shootouts with the far-Right groups and local militia. In early September, Ill Will sat down with Jarrod Shanahan and Zhandarka Kurti, authors of the Brooklyn Rail piece, “Prelude to a Hot American Summer,” to discuss this summer’s second wave of social unrest.

Other languages: Italiano

Ill Will: In an effort to think through this summer’s events, some of us have begun distinguishing for ourselves between two apparently distinct faces of the movement: the “social movement”, and something that, for lack of a better term, we’ve just started calling the “real movement”. On the one hand, there is the “protest” side of things, with all of its constituted left political organizations, ritualized marches, leaders on megaphones, self-appointed police (or ‘marshalls’), etc. What we call the “social movement” is the spontaneous tendency to translate antagonism or social conflict into demands, dialogue, peaceful disobedience, consciousness raising, etc. Even where this leads, in some special cases, to more radical forms of action, such as crowd self-defense or the occasional vandalism against state property, it does so in the mode of “pressure politics” aimed at influencing policy shifts such as ‘defunding’, etc. By contrast, we use the term “real movement” as a shorthand to name all those features of rebellion that bypass representation, discourse, and dialogue, and instead pursue the antagonism with the state and capital directly, even physically, if you will. In the past month, we’ve seen people burning down car lots and parole offices, attacking and emptying big box stores, and fighting the police…and wherever this occurs we always find a marked absence of mediating bodies such as political parties, leftist groups. We also see little or no concern for sculpting messaging or making appeals to the political class. It’s not understood as a moment of ‘dialogue’, it’s not ‘politics by other means’, or a plea for junior partnership. And we see nothing resembling any sort of democratic decision making process. In other words, with the ‘real movement’ we are dealing with a non-hegemonic form of antagonism that awaits permission from no one, pays credence to no authorities beyond its own perception of what to do and what makes sense, and generally does not understand itself as engaged in an appeal to civil society or as a nascent sovereign power.

For the first two months, it felt like these two faces of conflict, these two coexistent poles of the movement were more or less totally non-communicative. This fact seemed to be recognized by the authorities, for when the police would speak of “protesters” as opposed to “looters” and rioters they made it clear they were speaking of distinct groups of people doing quite different things, linked by little more than the moment that they participate in and the occasional shared slogan. For the most part, it seems they’re not wrong. How can we make sense of this two-sidedness?

Zhandarka: Well for starters, this important distinction has to be situated within the longer trajectory of the rise of Black Lives Matter from 2014 to our present moment. During the first wave of BLM protests in 2014, we saw Black and multiracial youth confronting police, turning over police cars, attempting direct action, taking over bridges and tunnels—all of the things that we would normally associate with militant tactics and the “real movement.” This militancy was interrupted by calls for peaceful protests by so-called respectable community leaders, who were ultimately successful in recuperating the energy of street protests into piecemeal liberal reforms like body cameras. In the span of six years, a lot has happened that has ratcheted up the social tension in this country. We have seen protests against racist police violence, resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline, an anti-austerity rebellion in Puerto Rico, a wave of teacher’s strikes in Virginia, Oklahoma and Arizona, a militant anti-fascist movement, etc. And this doesn’t include the impact of the global movements, such as those in Hong Kong, France etc. The repertoire of direct action grows more militant each year, as protestors in the streets become smarter and more confident. This has been accompanied by a growing disaffection with liberal reforms, Minneapolis being a prime example. This is all to say, that young people today are experiencing a profound politicization in a very short span of time.

Jarrod: Exactly. Whatever civic myths survived the Obama presidency are now being rapidly tossed out, including the idea that police can be made to work in the best interest of working-class Black people. In 2014 if someone tried to chant “fuck the police” at a BLM demonstration, they’d likely be scolded by fellow protesters about “not all cops,” or else accused of “putting people in danger” and so forth. Boy has that shit gone out the window. And in this rapid politicization, I have witnessed an increased permeability between the self-identified respectable side of the movement, and the folks who were taking risks, adopting militant tactics, not respecting the sanctity of private property. It seems to me that this new generation is moving in ways that suggest a blurring of the binary you set out between the real movement and the social movement.

For instance, there’s evidence that the two have overlapped considerably in the streets of places like New York and Chicago, and I’m sure other places. I was in the Loop on May 30th, the first big day of the rebellion in Chicago and I really could not believe my eyes. There was of course a traditional leftist convergence, with the endless chants which threaten “no peace,” from crowds that remain peaceful. But alongside this, was open and largely uncontested property destruction, attacks on police vehicles, confrontations between police and the crowd — all of this in broad daylight! I saw teenagers gleefully spraypainting “BLM,” “ACAB,” and “Fuck 12” on almost every conceivable surface. Having spent so many years in New York I was afraid for their safety! But the police were just completely overwhelmed, and I also noticed that none of the traditional peace police — the kind of protesters who call it “violent” to overturn a trash can and might just turn you in — were nowhere to be found. As the day wore on, it became clear that these acts of property destruction had become generalized practices — so somebody would be on the streets chanting “whose streets, our streets” like we’ve all done a million times, and then a minute later you would see them spray painting “Fuck 12” on the front of a Wells Fargo, and then they’d be right back in the march.

While the days that immediately followed May 30th saw the two poles drift further apart, with the looters and the protesters rarely sharing space, the resurgence of conflict in the 2nd half of the summer has drawn them closer together again. I’m thinking specifically about what I consider to be an important development in local politics here in Chicago, which revolved around the widespread looting on August 9th and 10th that you mentioned already, in the wake of a police shooting in Englewood. Now, a first interesting fact is that the victim did not die, and this bucks a lot of what we have traditionally understood to be the rules of the game. This time around, you had somebody who was simply wounded and who, according to the police (and you can take that with the requisite pound of salt), had been shooting at them. Yet nobody cared about the cops’ story, nor what they alleged that he did, and the fact that he was still alive didn’t stop what became 36 hours of looting and clashes in some of the most affluent neighborhoods in this city.

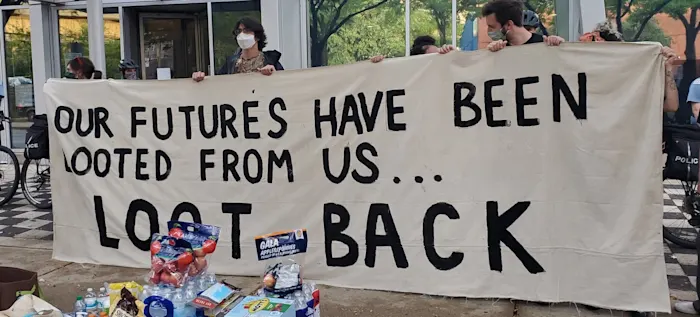

Now, this would be a classic example of how we would traditionally understand the real movement, in the terms that you use. So what happened the following night? Chicago Black Lives Matter, the standard-bearers of the social movement in a city where the figure of Saul Alinsky’s “community organizing” model still looms large, came out to do jail support for the people who had been arrested for looting. The city had been trying for months to divide the “good protesters”—peaceful, non-confrontational, amenable to working toward reforms, from the “bad protester”—the looters, the arsonists, the revolutionaries. This distinction maps fairly neatly onto the real/social movement binary you have advanced. Yet what we saw after a big night of looting, was the “good protesters” coming out to support the bad protesters! They even had a banner rejuvenating an ultra-left slogan from some years prior, “Our Future Has Been Looted, LOOT BACK.” One of their spokespeople gave a very stirring defence of looting, which she characterized as a form of reparations! It was masterful. This is not the kind of behavior that we have come to expect from the social movement side of things, who are supposed to be the foil of the ‘bad protester’ and ultimately act to deescalate militancy and steer movements toward non-violence and reform.

Ill Will: The fact that we have seen organized leftist groups vocally defending the smashing and looting of luxury shopping districts that occurred the night prior certainly feels important and new. A sort of unilateral “communication” took place, a gesture of acknowledgement on the side of the social movement that the real movement did in fact take place—as if the protestors were saying, ‘we see you’, ‘we back that’, ‘this resonates with us’.

However, it seems to me that the separation we observed still remains. We still have the looting on one side, and the protesters on the other. It’s worth recalling that at the same time that the jail support demonstration you described was happening, looting was still taking place in other parts of the city. Moreover, in the very form through which they showed their support, we easily recognize the tactical repertoire of the protester: to show up in front of a police station with a banner, stage a rally, give a speech, make demands, hand out water bottles, etc. So there’s a separation in time and space, a tactical difference, a demographic separation—and yet, across these differences, a kind of communication or encounter at a distance still took place.

Zhandarka: I think the context of the looting is also important here. The pandemic and the growing misery in terms of unemployment and evictions in tandem with militant tactics of the BLM protests have also led to increased acceptance of looting among ordinary folks this time around. I mean who wouldn’t want some nice stuff to either wear or sell later on if your job or household income is not guaranteed anymore? I was recently in the Bronx visiting my mom and I was getting takeout from the local Chinese food joint and listening to a 19-year-old talking about the pandemic with his friend. “And they thought the looting was bad, wait until Christmas.” And why? Well because everyone is masked up and the cops can’t identify people so easily. I think ordinary people with no intentions to attend organized protests but who surely bear the daily brunt of misery exploitation and police harassment have taken advantage of this moment, and rightfully so.

Jarrod: The terrain is certainly changing, and it is forcing actors to make tough decisions. So while speakers in BLM Chicago subjectively express affinity with the bad protesters, a greater proximity between the two poles is being imposed on the movement objectively by the state’s response to it. For instance, in the wake of the controversy BLM Chicago generated by supporting “Loot Back” as a legitimate form of protest, the social movement side of things got a taste of the cost of rejecting the good and bad binary. The following weekend in the Loop, a number of local activist groups led a march in the middle of the day from Millenium Park, which was attended by a few hundred people. However, in spite of following the familiar script that we all know by heart, it was met with brutal retaliation by the police, who largely outnumbered the demonstrators. The repression was vicious, with police beating kids, liberally spraying pepper spray, yelling and snarling profanities as they donned full riot gear to attack a crowd of extremely young people. The police ultimately kettled the march and forced everyone to empty all their belongings out of their backpacks onto the sidewalk—and forfeit all of their items for good—if they wanted to avoid arrest. It was sadistic and deliberately humiliating—in other words, the way CPD treats kids in the hood. My takeaway was that CPD was saying, ‘if you don’t want to respect the good and bad protester binary then fuck it, neither will we, and we’ll treat you all like the bad ones’.

Zhandarka: Yeah, and I just want to add that it’s also a matter of staying relevant. Since 2014 there have been growing tensions present within BLM between the liberal wing, who have demanded more milquetoast reforms, and the more radlib and left groupings who advocate defunding and abolishing the police. And for all the radical rhetoric of defunding the police, BLM has to also prove it in the streets by showing up for people when they are accused or arrested for looting and they generally have to speak to the kids in the hood.

Ill Will: After the rebellion in Ferguson became canalized into the more easily managed social protest paradigm, the broader Black Lives Matter struggle became ritualized, predictable, and fairly sterile for many years. In the past two months, by contrast, it feels as if we are seeing something like a double becoming. On the one hand, there’s the becoming that you were just talking about Zhana: what does it mean when protest groups like BLM feel compelled to respond to the real movement? The actions of social movement groups are rapidly outpaced by the eruption of rioting and looting. On the other hand, we have seen the global rise of a new type of confrontational frontliner culture reminiscent of the black bloc during the alter-globalization movement, with the difference that they are now mostly stripped of any explicit reference to anarchist ideology. This culture massified outside the US, first in Hong Kong, Lebanon, Chile and Iraq before finally touching down in Portland, Atlanta, Rochester, and other US cities this summer. As a result, we have seen a steady escalation of the sorts of protest tactics that young people have wanted to engage in. It’s no longer unusual to see kids showing up super geared-up with shields, lasers, respirators, helmets, goggles, armored gloves, and so on—even when it’s not really needed, just in case. There is rarely a demo you can go to today, at least in Chicago, where you don’t see someone wearing at least a half-face respirator. The meme-like circulation of these practices across the planet is starting to infect and transform the typical protest rituals we’ve come to expect. As a result, it’s important that we not continue to act as if things are as bad as they were for many years. We must be careful not to cling too tightly to fixed distinctions and expectations at the moment that we are seeing them eclipsed in practice. We should be attentive not to just ram everything that’s happening into old categories, if what we are seeing is more interesting and complicated.

Jarrod: We all know the danger of the formal organizations produced by these upsurges, and the specters of co-optation and inertia they raise. “Self-organisation,” as Théorie Communiste put it, “is the first act of the revolution; it then becomes an obstacle which the revolution has to overcome.” At the same time, there are aspects of the formally organized “social movement” that I would like to believe can benefit folks engaged in more direct methods of antagonism. It is difficult to sustain activities like looting and fighting police over a long period of time. The various BLM chapters, which have resources, social media reach, and an enduring presence in the streets, can bring continuity and coherence over time. Ideally, their function should be to loop a new generation of disaffected young people into a practical framework for social crisis and the struggles it produces. Constituted groups can of course become a fetter to the unfolding of a struggle, but at present it feels important that there be forms of collective identity having some kind of coherent body (no matter how loosely configured) and the means and ability to keep things simmering between boils. If Trump and Barr’s repression of the movement continues to intensify, or else if the movement escalates on its own terms, we may see individual people or entire segments forced underground. Some kind of connection to more respectable above-ground organizations would be an essential part of not being crushed in such a moment. And to be clear, that dynamic is already developing, with considerable street militancy occurring behind the screen of a more orthodox social movement. As long as the latter does not outright denounce the former, the possibilities for symbiosis are auspicious for advancing a protracted struggle.

Zhandarka: I agree. It’s still quite easy for the right and liberals to politically isolate looters and to divide the movement. I don’t know how much of this division can honestly be avoided, because we know that even where movement identity has been more coherent, the ideological narratives about good protester/bad protester have been an integral aspect of how counterinsurgency has unfolded. But some degree of organization could at least anticipate and respond to these divisions.

The fact that white people are looting and rioting is also important, I think. Their participation points to a shift in the terrain of whiteness today. In the past when white people have rioted it was often aimed at Black people. For instance, when Black people would move into all-white neighborhoods they were terrorized and harassed by white mobs and rioters. During the Chicago riot of 1919, mobs of whites, many of them young people, brutalized Black residents, provoking heavy clashes resulting in over three dozen deaths (23 Black and 15 white) and over 500 injuries (two-thirds of them Black). Owing to their ties to machine politics and the police, white folks were never arrested or prosecuted. In the post-war period, white mobs also firebombed the homes of Black people that were moving into white neighborhoods. In the 1960s, on a national scale, whites who supported Civil Rights or even Black power and national liberal struggles did not participate in rioting. So, the participation of white people in riots is an interesting development that complicates the narrative of good/bad protesters.

Ill Will: I wonder if we can relate these two points somehow. In terms of this distinction between ‘good’ and ‘bad protesters’, not only has there been a becoming or a shift within leftist groups (as we have noted already), but it also feels like we are also seeing the beginnings of a form of policing that doesn’t recognize this difference. You mentioned the bloody repression of the demo in Millenium Park, but this felt equally true in Portland and Kenosha. For their part, Chicago police were given good reason to question the so-called innocence and good will of the Left during the demonstration at the Columbus statue in Chicago back in July, which resulted in them getting smashed by hundreds of cans of LaCroix that appeared without warning out of nowhere. Since then, when shields come or umbrellas are pulled out at demonstrations, Chicago police now have a memory of this betrayal. I’m reminded of an anecdote that used to come up often in the Race Traitor journal back in the 1990’s: when a white man would get pulled over by a cop, there’s a presumptive loyalty based on skin color, a sort of tacit psychological assumption on the part of the police officer that, ‘I’m encountering a white ally here’. The point of the anecdote, of course, was to encourage white people to destitute this presumption of innocence, by fighting the police alongside their Black brothers and sisters. Yet this sort of presumption of innocence surrounded the activist Left in Chicago for years: for the most part, police knew they needn’t worry about things getting out of hand, that organizers would internally govern any unruly elements in the crowd. After the Columbus Statue action on July 17th, however, the police are now forced to approach the Left like a jilted lover: ‘we used to trust you…now you’re no better than the hood kids’. This fact, combined with the second wave of looting, has meant that they are increasingly acting in ways that suppress in practice any distinction between the social movement and the real movement. On the one hand, this should worry us, as it implies a form of counterinsurgency geared toward open violence, including the use of guns and so forth; at the same time, it also has the potential to shatter illusions that the Left carefully guarded and reproduced for years. Can we speak of a “treason to Leftism” here?

Jarrod: My line right now is most of us who have been around movements know all the bullshit you can expect from the radical liberals, the hucksters, the fake revolutionary non-profits, and all the rest. Fine. Instead of resting on that analysis, though, I say let’s pay attention to where it is not happening. Most of these actors are not static entities, and we are living in a moment that will leave only the most inveterate partisan untransformed.

Zhandarka: Let’s not forget that soft counterinsurgency is a liberal invention. In all these liberal bastions like Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York it’s been democratic mayors who have unleashed the police on protestors. Chicago is an interesting case because it has been the mecca of Black politics since the early 20th century.

Jarrod: Well, they are the hardest hitting counterinsurgents in the room. I mean, that’s where today’s soft counterinsurgency comes from, dating back to the 1960’s. Large Democratic cities like New York, which saw a large influx of Black workers during the Great Migration, learned during the 1960’s that force alone could not contain the urban rebellion, and thanks to some of their own money, and a lot of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society funding, were able to construct bulwarks against insurrection within the left. A lot of the non-profit and hyperlocal political machine apparatus that we know today dates back to that period. And a lot of these young people we see in these left-liberal nonprofits are supposed to be the next Obama; many local groups are hooked right up to the same Ford Foundation-funded machine that produced the first Obama. For the time being, some of these young people seem to be bucking this role in a very public way.

Zhandarka: Today’s young generation has far fewer illusions to shake off. Whereas previously there was more hope for reforming the police, especially when Obama was Commander in Chief, today that hope has dissipated. Younger people today understand that police routinely violate Black people and that is part of their job. Yet, there is still a significant large segment of the Black liberal class who thinks we just need to reform the police. But I mean what will Biden and Kamala do? Young people are watching BLM unfold, and seeing that in 2020 the Democrats’ answer to police violence is to elect two people who have supported the ramping up of policing and mass incarceration. It’s a total slap in the face. I think, as happened with Black Power in the 1960s and 1970s, this new generation is seeing that representation is not power.

Ill Will: Absolutely. The emancipatory struggle in America is rapidly shedding the weight of its democratic baggage. It’s letting go of the hindrances that still tethered it during Occupy. Discursive practices are either falling by the wayside, or merging with memes and shitposts and becoming just much more fluid. This has opened the field for a much more combative repertoire of what people consider interesting and productive. The young generation—particularly lower class kids—would rather riot and throw things at police than sit around in a general assembly awaiting their turn to talk. That’s largely a good thing. One downside of it, however, is that we lack any symbolic framework through which to talk across racial lines about what it means that white folks are showing up in this fight alongside Black people, and demonstrating their practical rejection of white supremacy through their willingness to endure police violence to advance the antagonism. We lack the means to speak in positive terms about what it would look like to live in a shared and mutually empowering world together, without policing one another. So it feels like even though gesturally (i.e. in terms of practices) there are innovations happening every single week, the situation remains symbolically frozen.

Jarrod: It is not an insignificant fact that the two comrades who were murdered in Kenosha were white. It seems particularly offensive to a lot of these right-wing militia types to see white people in the streets putting their lives on the line in the name of Black life. And a lot of them have joined up with this movement. Maybe I’m a pessimist here, but I do not think that people are willing to lay down their lives for a cause that they do not see as their own. What this means is that these white people are not showing up as “allies”, they are partisans participating in a generalized rebellion against life in the United States. Certainly, the treatment of Black people by police is one of the nastiest features of American life, and we have to understand it as the low bar by which most lives are devalued. Accordingly, this is a moment when the high walls between the so-called races are being chipped away in the streets. Sadly enough, in such a moment, we see that the walls between the races are heavily policed, and not just by the right.

Zhandarka: Americans live a very segregated and atomized existence. For this reason, it has been amazing to see this multiracial explosion in the streets. It is an important development that so many young white people are drawn to anti-racism and marching in the streets. At the same time, many white people still see police violence as an issue that affects only Black people. Of course, Black people are getting killed. Yet policing is also a societal issue, an issue that touches the core of our humanity. As long as white youths don’t see their lives as also being messed up by this bigger system, the struggles won’t gel. I think about the countless economically devastated rural places where young whites face poverty and all the problems that come with it, but don’t have the language to make sense of their own misery and how it is connected—in spite of important differences—to that of Black people, and how the system functions as a whole. But part of me is optimistic. If there was a time to connect things it would be now. We are seeing that Covid continues to rage on, we’ve seen news of states running out of unemployment money, more and more young people are being kicked out of the shitty low paying jobs including restaurant industry, retail.

Ill Will: Amidst this ramping up of “citizen defection” from progressive politics, and the propagation of a frontliner culture that is breaking-away from the fetish of democratic proceduralism, identitarian leadership, citizenly dialogue or ‘demands’—at the same time, we are seeing Trump and the far-Right attempting to provoke these radicalizing social movements into ballistic confrontations. Their assumption is presumably that the Left will not be ready for, nor able to stomach such a confrontation, which is almost certainly true. How do we intensify the defection within the Left, while at the same time holding the window open for people to join in who are not classically part of it? How can we ensure that the struggle remains joinable by the kinds of people who don’t have any advanced knowledge of guns or the capacity for armed struggle?

Jarrod: I think this is the challenge that we need to meet in response to the increase in armed Right-wing violence and state repression. Of course people should defend themselves, and it may come to a time where we need armed self-defence at our demos in places like Chicago the way it exists already in the Pacific Northwest. But this is not the same thing as saying we need to match the right, tit-for-tat in piling up firearms and preparing for some kind of war, which a lot of smart folks have pointed out in the last week or so, would really be between two very small groups of comparatively young and adventurous people. I do not think that is the horizon that we should aim for, and to avoid it, the onus is on us to clarify not just what we are against, but what we are for—the world we want to build, and how we see ourselves as getting there from this present calamity.

Zhandarka: To bring it back to this moment. Even if a vaccine is developed that doesn’t mean that things will go back to normal. So, we need to take advantage of the opening this moment has provided to connect struggles and clarify our position. How do we make connections between the struggle against police violence and the crisis that COVID has laid bare? The brewing rebellion is a great start! But also millions of Americans are silently suffering through this global pandemic. And we have yet to see major resistance in workplaces or schools. Most Americans have generally accepted the pandemic and rearranged their lives to accommodate it. A majority of people are going to work and school wearing masks and wondering “am I going to die today?” But this accommodation may not last. People may get fed up, all sorts of things can happen. So, we need to make connections across the different crises that are making themselves evident in American life but we also need to stand for something. And I think there is a hesitancy to say what “we” are for, and I believe that is a grave mistake. The Right wing and the liberals all stand for something, and that is a return to more deaths and more misery. For the past decade, “we” have been finding each other in the streets, in protests, in organizations that have fallen apart for various reasons. This is all good and we should tighten these bonds, squash the beef between these small milieus that existed in the past. But we also need to have the language, the political language to help young people participating in these protests make sense of the world and the vision of the future. We have to develop a way of talking about the idea of life we want to embrace.

-September, 2020