Theory of the Party

Phil A. Neel

Other languages: Español, Deutsch, Română, Türkçe, Français, Português, Italiano

The prices are higher. The summers are hotter. The wind is stronger, the wage weaker, and fires kindle more easily. Tornados rove like avenging angels through the cities on the plain. Something has changed. Plagues burn deep in the blood. Every other year a great flood descends, jeweled with corpses, to turn the soil of another punished nation. Behind us lies the great carboniferous bonfire of human history. Ahead, a dimming shadow cast by our own bodies, caught and thrashing the gyre. Anyone can sense that something is very wrong — that an evil has seeped into the very soil of society — and everyone knows that the powers and principalities of this world are to blame. And yet we also all feel powerless to enact any sort of retribution. As individuals, we see no way to exert any influence over the course of events and must simply watch as they wash over us. We find ourselves disarmed and alone, faced with a dark future in which shivering horrors stalk just beyond the border of our sight, dragged inexorably forward as the chains rattle and the sounds of torment echoes back from the world to come.

But, with the right kind of eyes looking in the right places at the right times, you can maybe see the grim shadow of the future splintered by flashes of otherworldly light: blindingly bright moments in which the prospect of justice appears for a fleeting second. The precinct burns, the workers flood out of the factory, committees form in the streets and the villages, the government falls as softly as a feather, three bullet casings drop like dice — an incantation etched into each, as if to summon something greater. Perhaps you have felt it. The heart grows light. Angelic fire courses through the flesh and, for that one breathless moment, something immortal inhabits us. The blade of the meteor cuts across the stomach of a moonless sky and then we blink and it is gone: the National Guard is called in, the unions negotiate a return to work, the committees dissolve, the overthrown president is superseded by the military council, the dead CEO is replaced by a living one, and police bullets fall from the glass towers like a cold, hard rain. But the light cannot be unseen. As a result, this very defeat is itself an awakening. We realize, slowly, that the collective, expansive character of the evil that plagues us requires a collective, expansive form of retribution. Social vengeance requires a social weapon. The name for this weapon is the communist party.

As the cadence and intensity of class conflict increases, organizational questions are posed with increasing frequency. These first emerge as immediate, functional questions facing specific struggles and scaling alongside them. In the wake of any given struggle, broader questions of organization then arise, taking on both a practical and theoretical dimension. In practical terms, the question largely focuses on the activity of faithful partisans who are left without an immediate object of fidelity. They express a residual subjectivity evacuated of its mass force. In more blunt terms, these individuals are “leftovers” from a certain high tide of class conflict. At this level, the question is usually posed as an issue of what this fragmented “we” might do in the interim between upheavals. As a result, the process of inquiry itself is often weighed down with a frustrated zeal, debates mobilized in eviscerating circles of moral recrimination driven more by a spirit of self-punishment than any earnest interest in analysis.

Nonetheless, the same line of questioning soon branches into a wider web of inquiries related to “spontaneity,” the relation between structural trends (in employment, growth, geopolitics, etc.) and the likely forms of organization that will be adopted by proletarians beyond this leftover layer of partisans, and, of course, how these partisans might engage with such organizations. From here, the inquiry is elaborated and abstracted into its theoretical dimensions, becoming a “question of organization” as such. Though inextricably linked to larger theories of how capitalist society operates and what a different world should look like, this question of organization also occupies a liminal position, simultaneously abstract (as a theory of revolution) and conjunctural (as a necessary practical step in the construction of revolutionary power). On their own, each of these dimensions quickly decays: the necessarily abstract aspect becomes a mechanical determinism in which a single schema is applied in all cases (whether of the “affinity group” or the “cadre organization”); while the necessarily conjunctural aspect becomes a form of activist inaction in which the very flurry of local “organizing” activity (usually some combination of issue-based advocacy, service provision, and media work) is itself a form of disorganization hobbling the partisan project.

Unifying these divergent aspects requires forms of abstraction built from and materially linked to conjunctural moments of revolt. Any discussion of organization must therefore occur at either an entirely localized scale — discussing how these people might organize in this situation — or as the generic and syncretic collation of the multitudinous acts of organization that already populate class conflict, as experienced by participants, in an effort to think through their limits and refine our understanding of what, exactly, “organization” even means. Here, I hope to bridge these two functions, presenting a theoretical intervention that operates at a relatively high level of abstraction — informed by both careful study and on-the-ground experience within the rebellions that have shaken the world over the past fifteen years — which was initially crafted as a local intervention intended to help sharpen specific organizational projects emerging from specific social ruptures. In other words, what follows is a theory of the party designed to help catalyze concrete forms of partisan organization.

Key Principles

As we slowly emerge from the long eclipse of the global communist movement, we find ourselves in a paradoxical situation, inheriting both too much and too little. On the one hand, we are left with a rich, though largely textual, inheritance of intellect and experience built up by past generations. And yet this history is now distant enough that it proves too easily romanticized, as once-dynamic programs and polemics are frozen into schematics and the fiery passions of the era chilled to a numbing nostalgia. On the other hand, in terms of concrete experience and mentorship, the long winter of repression has left us with nothing but scattered remnants. The parties of the past were all melted down in the alembic of repression. The great minds were broken. Betrayal followed betrayal. The brave were crushed and the cowards fled. Only the dead remained pure in their silence. Our generation was therefore raised in the wilds, our communism uncultivated and feral, shaped only by the raw force of capital. As a result, we now find that any inquiry into the “question of organization” is immediately weighed down both by this overabundance of too-distant history too easily rendered into overwrought fan fictions, and by the lack of any living institutions carrying on the incendiary spirit of the partisan project.

Collective subjectivity

On its face, the question seems obvious: what is needed is more “organization.” However, once broached, the basic definition of “organization” proves murky, disappearing in the very attempt to articulate what, exactly, is meant. Often, the question itself serves as little more than a bludgeon. The pattern is familiar: the “theorist” looks back on recent struggles, diagnoses their obvious limits, attributes these to a conscious choice by bad or at least naïve actors who have selected “horizontal” or “leaderless” forms of struggle to their own detriment, and then then prescribes “organization” as the cure-all that should have been chosen in the past and must be chosen in the future.1 In so doing, such “theorists” first fail to offer any actual image of what “organization” might have looked like in the actual situation facing the rebels, since there was obviously no revolutionary army lying in wait for the necessary commands. More importantly, in their own fanatic obsession with correct ideas, they also fail to grasp the most basic dynamic of social revolt, in which a form of collective intelligence emerges from mass action in excess of the thought of any individual participants or even programmatic groupings of political actors.

The real question is instead entirely different. As anyone who has participated in any of the major rebellions of the past fifteen years can tell you, there is never any shortage of such “theorists of organization,” or even miniature militant formations composed of correct-minded “cadre” operating in the midst of the revolt, all actively advocating for their own view of organization linked to a coherent political program. Why, then, does no one seem to be interested in what these individuals are offering? The reason is usually quite simple: they are not offering anything at all, other than the word “organization” itself, repeated ad infinitum. Though they themselves are convinced otherwise, such individuals and their so-called “organizations” usually provide no concrete tactical experience or strategic knowledge and are therefore incapable of pushing the revolt beyond its limits and building substantial forms of proletarian power. For this reason, they are quickly outmaneuvered by the collective intelligence of the rebellion itself. Even in the rare cases where they do have something to offer, they fail to organize themselves effectively enough to convince anyone to care what they have to say in the first place. In other words: they have no means of interfacing or engaging with the wider rebellion.2

This approach to the question of organization is itself a symptom of concrete tactical limits evident in the inability of rebellions to enact meaningful social change or generate forms of proletarian power that can survive in their wake. But it is also backwards, taking large-scale, programmatic organizations that emerged as the result of long decades of revolutionary struggle in earlier periods of history as a starting point for struggles today, as if such entities could be revived through sheer force of will. The actual process of organization is the exact opposite: in the midst of struggles and rebellions of various intensities, myriad forms of organization (often mischaracterized as “spontaneous” or “informal”) emerge from the tactical puzzles posed to the collective intelligence of participants and, only once this practical substrate of popular power is formed, can more “strategic” or theoretical forms of larger-scale coordination and power-building begin to take shape. In other words, those who enter into the rebellion demanding that “we get organized” presume a “we” that does not yet exist.

The question of organization must first focus on building collective subjectivity, not commanding it. The starting point of the theory of the party is therefore not a question of how “we” should get organized. Instead, the question is twofold: how can a specifically communist form of revolutionary subjectivity emerge out of the distinctly non-communist, everyday struggles of the class? And how might specific fractions of individual communist partisans produced by these struggles intervene back into these conditions in order to further elaborate this partisan subjectivity in and beyond individual struggles? The emergence of the party is as much a process of collating and learning from the collective intelligence of the class in the midst of incendiary conflicts as a propositional intervention or programmatic synthesis. Rather than looking back at recent uprisings in a purely negative sense, understanding their limits as emanating from incorrect ideas, partisan inquiry sees these failures as primarily material limits, expressed tactically, which also carry with them a propulsive, subjective force. As a result, they can be read in a positive sense as an accumulated repository of collective experimentation, albeit only actualized as such insofar as these experiments are made to inform future cycles of revolt.

The tactical vanguard and the sigil

The tactical limits that emerge to constrain any social rupture can only be overcome through action, and only action elaborates collective thought. Action is the necessary interface between the isolated thought of individuals or groups and the mass subjectivity expressed in the broader rebellion. Conventional approaches to the question of organization tend to assume that action follows from individual moral or political sentiment. These approaches are “discursive” in the sense that they presume that political action is preceded by the intellectual proposal of a certain program. In other words, the assumption is that people are convinced to adopt certain political ideas through conversation, polemic, or propaganda, and that these ideas then imply the adoption of certain strategic orientations and affiliated tactical practices. But history demonstrates the exact opposite: political positions emerge from tactical action rather than the discursive imposition of moral or ideological arguments.

Putting the program first is therefore backward and, in effect, often serves as a form of disorganization. In reality, organization emerges through the practical overcoming of material limits, trailing its intellectual, aesthetic, and ethical commitments behind. In other words, people do not join organizations, support them, or adopt their political positions, symbology, and general dispositions en masse because they agree with them. They do so because these organizations exhibit competency and strength of spirit. In military theory, this process is understood as a struggle for “competitive control” over an open field of conflict.3 Only after this concrete leadership in action has been established do people become receptive to the more abstract leadership in program and principle. Thus, even if the propositional approach possesses a theoretically insightful and practically useful program, this program will nonetheless be unable to influence the course of events so long as its adherents lack the ability to conduct the tactical interventions necessary to interface with the collective intelligence of the uprising.

Moreover, these programs should themselves be seen as living articulations of their political moment. Even their most expansive structural analysis expresses a form of collective intelligence localized to a particular time and place. As a result, they are not only provisional, but also must be appended to and follow from action. This process then reshapes these positions themselves and generates novel forms of political thought. Politics thereby spreads and elaborates itself through this tactical interface. By committing brave acts that break through the tactical limits of any given struggle, the symbology of any given group of partisans can take on an additional memetic force, becoming what I refer to as a sigil: a flexible, symbolic form that compresses and broadcasts a certain dimension of the rebellion’s collective intelligence in a simplified visual grammar and, in so doing, taps into a more expansive form of subjectivity (the historical party, explored below).4 In their most rudimentary form, sigils operate at the aesthetic level: things like the yellow vest or yellow helmet from the struggles of the late 2010s. In their more elaborate form, they encompass certain tactical practices or organizational dispositions as transmitted through a name and a package of minimal practices: workplace councils, neighborhood resistance committees, public square occupations, etc. The sigil renders tactics into broadly replicable forms and offers a minimal passage through which the uninitiated (i.e. that section of the population normally deemed “apolitical”) are able to enter into the moment of rupture. The sigil therefore opens action to a broader social base of participants regardless of whether they adhere to any discursive or programmatic points of unity.

The sigil thereby draws a preliminary form of collective subjectivity up from the surging tide of history. It simultaneously summons a partisan force out of the class through its seemingly occult power and, as a practical waypoint orienting concrete tactics, also structures this amorphous subjectivity into minimal forms of organization. Although memetic, the sigil is not primarily aesthetic and does not rely on any particular technical medium for its propagation. Sigils only emerge through tactical example. Political dispositions then trail behind the sigil, serving as the messy, mostly subconscious articulation of these radical acts after the fact. Someone wearing a yellow helmet smashes the windows of parliament; the package of political sentiments and political conflicts associated with this symbolic act — in this case, rightwing localism in Hong Kong — can then be spread further through memetic replication, allowing the associated symbols and practices to more easily hegemonize the aesthetic and tactical space of the rebellion, further reinforcing the charisma of their affiliated political positions.5

Subsistence struggles

An equally important distinction is that between the partisan project, which can only be constructed in and through larger-scale social ruptures, and more constrained forms of struggle visible in the continual simmer of class conflict.6 All communist organizing must, of necessity, orient itself around the struggles over subsistence that continually emerge across the class, generated by the contradictory dynamics of capitalist society. Even though more expansive political events exceed these struggles — and this excess is the real site at which a subjective force emerges (see below) — initial conflicts over the terms and the enforcement of subsistence nonetheless lie at the origin of these events. Similarly, these subsistence struggles structure the field in which organization must persist between specific uprisings. All communist organizing must, therefore, be continually capable of translating itself into concrete class interests by taking on practical functions in relation to both the specific terms of subsistence at any given moment and the specific methods through which subsistence is imposed on the class.

However, communists must also confront subsistence struggles as a limit to be overcome. Since the demands and grievances expressed by such struggles are imposed interests emanating from identities that are, ultimately, constructed by capital (as is visible in racist opposition to migrant labor, for example), doing nothing but defending material well-being (i.e. fighting for real gains for the working class) ultimately strips a communist organization of its fidelity to the larger communist project. The incendiary pulse of any given struggle is bled out through the thousand small cuts of compromise. In fact, “victory” in any given subsistence struggle is often itself a defeat: the murdering cop is sent to trial (perhaps even found guilty), the wage increase is won, the environmentally destructive development project is cancelled, the controversial law is retracted, the president steps down (and power passes to the “transitional” government). By far the best way to defeat a communist movement is for the party of order to concede real gains within subsistence struggles and consolidate these gains under its own banner.

Broadly defined, subsistence struggles are those focused on concrete issues of survival under capitalism. Although these operate along multiple dimensions, they may be loosely divided into struggles over the terms of subsistence, and struggles over the imposition of these terms on the population. The former tend to focus on relatively narrow distributional issues of access to social resources while the latter tend to focus on the broader issues of survival and dignity that arise through the apportioning of these resources.

The first category, struggles over the terms of subsistence, is almost always centered in some way on the price level. These can be further subdivided into struggles over general commodity prices (the cost of living, especially rent), struggles over the price of labor-power (wages, pensions, and other employment benefits), or struggles over the pricing of services and resources funneled through the state (welfare, infrastructure, education). Institutional differences between localities ensure that certain issues (such as healthcare) may lie on one side or the other, or span both. Sudden price spikes or reapportionments of social goods can certainly trigger large-scale protests, and long-run inflation and corruption can increase the frequency of subsistence struggles. However, as a rule, these struggles are more easily recuperated into the policy sphere, and only take on a radical edge in extreme conditions or when partisan organizations exist to push them in this direction. For this reason, their political expression tends toward a simple populism focused on the restoration of stable price levels, presumed to have been distorted by extraneous interventions (by some fraction of rentier elites) into the otherwise efficient functioning of the market.

The second category, struggles over the imposition of these terms of subsistence on the population, focuses on raw survival and dignity in life and work. The most obvious are the recurrent, smaller-scale protests against police murders of the poor in a given neighborhood (at least those that are not yet mass uprisings), abolitionist struggles against incarceration, purely local protests against deportations, etc. But these sorts of struggles also intercut the others. In the workplace, for example, struggles over the terms of subsistence are often motivated less by their immediate goal (of, say, increased wages) than by opposition to authoritarian managers, or differential treatment by race or migration status within the company. Such conflicts are often the most incendiary issues on the shopfloor, as anyone who has organized any workplace knows. Similarly, when struggles over the terms of subsistence are met with police violence, they also immediately become struggles against the very imposition of these terms on the population. These struggles are therefore broader than those of the first type, quickly taking on more overtly political characteristics and often expressing themselves as struggles against domination as such.

Unlike struggles over the terms of subsistence, which can often be very roughly predicted by movements in policies and price levels, struggles against the imposition of these terms on the population are extremely difficult to forecast. Beyond the general insight that such struggles will ignite most easily in certain areas and among populations subject to extreme abjection, and that they will spread most effectively when a particular case is widely publicized, it is difficult to say, for example, when any given police killing will lead to a protest, and effectively impossible to say when it might spark a widespread revolt that then exceeds its initial bounds. As a rule, however, these struggles are more difficult to recuperate via existing institutions and are more easily propagated, since their very suppression sparks further revolts.

Particular confluences of subsistence struggles serve as the grounds from which mass uprisings emerge, which will then exceed these initial bounds and thereby cease to merely express these underlying subsistence struggles. Though both modes of subsistence struggle play their roles here, it is usually the second type that acts as the immediate trigger. The ongoing protests in Indonesia are a good example: the steady simmer of struggles over the terms of subsistence (cost of living, state apportionment of resources, access to employment, etc.) provided the set of basic grievances for an initially limited set of protests. These then exploded into a mass-scale youth uprising after the police brazenly murdered a delivery rider and then violently suppressed further protests, resulting in still more deaths. Nonetheless, even aggressive struggles against the imposition of the terms of subsistence nonetheless exist within the same limits of any subsistence struggle, expressing concrete interests that can then be co-opted by the party of order.7

Ecumenical and experimental

Any claim by any party to possess the one true path to revolution is obviously laughable. Revolutions are not monoculture, either in theory or in practice. The one thing that should unify communists, then, is a strict opposition to sectarianism and any pretensions to certainty. Our practice must be ecumenical and experimental from the very beginning, cultivating, collating, and catalyzing differences that are then put into constant conversation with one another. Only by folding heterogeneous approaches into our efforts can we expect to generate novel solutions to the myriad intellectual and tactical limits that confront any revolutionary process. This requires maintaining a posture of openness toward apolitical or antipolitical currents, as well as to those whose stylistic or tonal expression of politics differs from our own, rather than clunkily transmuting such aesthetic differences into allegedly political critiques.

At the same time, ecumenicism is not equivalent to eclecticism. And experimentalism is not the same as romanticizing novelty. The point is not to simply “borrow what’s useful” from any given source to create a happy patchwork of radical ideas, nor to obsess over some “new” tactic or disposition in the struggle (almost always an old one, in fact), but instead to draw out and integrate fragmentary truths into a multitudinous but nonetheless coherent communist idea broadly shared by all partisans, each elaborating the same basic project in myriad dimensions. Communism coheres through the very diversity of expressions that compose it. But this diversity requires, as its grounds, that these expressions nonetheless circulate around a certain set of minimal conditions, much as a pendulum oscillates around a distinct (but also virtual or emergent) center of gravity. Simplified as much as possible, these conditions might be summarized as: the belief that the goal of such a project is the creation of a planetary society operating according to principles of deliberation, non-domination, and free association, using the vast (scientific, productive, spiritual, cultural, etc.) capacities of the human species to rehabilitate its metabolism with the non-human world.

These minimal conditions then unfold into a series of further questions and conclusions to be elaborated through the partisan project itself. By definition, any society operating according to these principles must abolish the indirect or occluded domination embedded in value as a social form (including money, markets, wages, etc.) and in the forms of legal and illegal identity that follow from it (i.e. one’s status as a “citizen” of a “country” with differential rights), as well as direct forms of domination expressed in the state, in mandatory inclusion within authoritarian family units, in patriarchal or xenophobic customary practices, etc. Similarly, since it entails a phase transition between fundamentally different forms of social organization, communism must emerge from a revolutionary break with the old world and cannot be slowly approached through the evolutionary means of gradual reform and development of the productive forces. From this follows perhaps the most important dividing line: that which separates communists from all those who fear, dismiss, or treat as infantile the riotous behavior of the crowd in the moment of the uprising, preferring either orderly and “peaceful” protest tactics or some mythic form of militant discipline, as if insurrections were surgical military operations rather than messy, mass uprisings.

On the surface, this appears to pose a paradox: if we take unity to be the synonym of sameness and therefore the polar opposite of diversity or difference, these conditions would take on an exclusionary character contrary to the spirit of ecumenicism. But what is proposed here is not a strict or supervening unity that overrides and homogenizes subsidiary elements, but merely a requisite measure of coherence. While these minimal conditions must be enforced in order to ensure an ecumenical environment that allows for the proliferation of truly communist ideas, this process of restriction is simultaneously generative. Without such enforcement, non-communist “radical” or “leftist” ideas that hew more closely to the common sense of popular ideology will quickly wash out any communist content. Though it will be important to remain in conversation with these vaguely “socialist,” “abolitionist,” or “activist” currents — since their own contradictions tend to lead a minority of more intelligent participants toward communism — it is even more important to remain distinct from them, refusing to liquidate the communist project into this lukewarm radical liberalism. This then enables us to establish the foundation for our own experimentation, allowing communist partisans to attempt different forms of intervention and engagement and then collate the results in a clear-headed fashion.

Theory of the Party

When we speak of communist organization, we are not speaking of organization in general. Though various theories of organization as such — drawn from cybernetics, biology, or even examples of the coordinating structures used in corporate or military settings — will obviously be informative, they also lack a necessarily transcendent feature: the partisan orientation toward an idea. Partisanship requires a theory not simply of organization but of party organization specifically. Moreover, for communists, it is a question that can only be formulated through a “theory” of the party elaborated in practice: continually constructed from the practical lessons learned in long histories of class conflict, and always fed back into this conflict to be tested and further refined. Though this theory might, at any given moment, be collated and articulated by specific thinkers, it ultimately expresses a collective inheritance continually relearned and reinvented through the action of the class.

The historical party (invariant)

At a high level of abstraction, we can break the theory of the party up into three distinct, yet interrelated concepts. The first of these, the historical party, is also the broadest, encompassing the sum of the seemingly spontaneous forms of mass-scale unrest continually reemerging from struggles over the terms of subsistence. It is spoken of in the singular: there is a single historical party roiling beneath capitalist society in all locales and eras, though it only becomes visible in its upwelling. Marx also refers to this as the “party of anarchy,” since it is treated as such by the “party of order” that tries to suppress it, and by the “anti-party” that tries to foreclose it entirely.8 This party is always at least dimly traceable in the simmer of subsistence struggles. However, subsistence struggles on their own do not express a communist content, and do not “naturally” take on a partisan character. Just the opposite: subsistence struggles tend to express the determinate interests of socially sculpted identities and, as a result, their most probable path is to develop relatively limited, representative demands that, even if expressed via “grassroots social movements,” operate entirely within the realm of conventional politics: petitioning existing powers for reform, appealing to public sentiment, and even asserting the insular interests of one segment of the class against others.

Subsistence struggles on their own are best understood as expressive forms of political consciousness, in which “subjectivity” is reduced to the mere representation of social place. By contrast, the emancipatory horizon visible in the motion of the historical party emerges only in excess of representation, though it also necessarily emerges from a specific social location (i.e., from the distinct conflicts and arrangements of power peculiar to that place). Revolutionary subjectivity is the elaboration of a practical universality in tension with its own conditions of emergence.9 Thus, the existence of the historical party is most apparent when subsistence struggles reach a certain intensity, at which point they take on a self-reflexive character that overspills the bounds of their initial grievances. In conventional terms, this is the point at which singular struggles become multifarious “mass” uprisings. These excessive social ruptures can then also become political singularities, or what political philosopher Alain Badiou refers to as “events,” which warp the fabric of what seems possible in a given locale and thereby reshuffle the coordinates of the political landscape in their wake.10

On its own, the historical party is a not-quite-subjective force. Though it certainly generates forms of “class consciousness,” the historical party itself operates at a level best described as the subconsciousness of the class. It therefore often seems inchoate, inscrutable, and reactive. Moreover, the intensity of any given reaction is often extremely difficult to predict. For example, police killings happen all the time, but only certain cases — in essence identical to any others — spawn mass uprisings. Nonetheless, the motion of the historical party is also obviously connected to long-run structural trends in a given locale and in capitalist society as a whole. In fact, we can even think of it as being propelled forward by the inherent tension between socially extant identities (the anti-emancipatory “political consciousness” of subsistence struggles and social movements) and their excessive over-expression in the event.

This accounts for the ebbs and flows of the historical party, which are determined by the confluence of these objective trends and their subjective elaboration in class conflict, and also for its invariance. The fundamental laws of capitalist society do not change, and crisis and class struggle are the means through which this society reproduces itself. For this reason, subsistence struggles will always arise and, thrown together at a certain rate and intensity, will always tend to overspill their own bounds, generating political events in which the historical party becomes visible. Through its conflict with the extant world, the historical party then projects forward an image of communism in the negative.

This image is invariant in two senses. First, since the basic social logic of capitalist society is unchanging, the minimal conditions for its destruction also remain the same. We can think of this as a “theoretical” or “structural” invariance. Second, the process through which revolutionary subjectivity takes shape is also invariant, in that communists will always confront the same central conundrums and be met with similar responses by the forces of social order, resulting in a strategic field that is, in fundamental ways, identical to that faced by revolutionary forces in the past. We can think of this as a “practical” or “subjective” invariance.

The dispossession at the root of proletarian existence, and made apparent in everyday subsistence struggles, along with the possibility of proletarian power made apparent in the political excess of the event, thereby come together to create a potential, virtual, or spectral image of communism that is always visible to certain participants and not others, due to some combination of circumstance and temperament. By tracing out the limits of any given struggle, these participants find themselves elaborating a larger pattern, principle, or truth: the invariant idea of communism. For this same reason, events open directly into a certain dimension of the absolute, linking together uprisings from vastly different times and places into the same eternity which is itself a reflection in the present of the potential communist future.

The formal party (ephemeral)

Formal parties represent attempts to elaborate this pattern in and beyond events, etching that invariant idea into the ephemeral matter of self-aware assemblies of individuals. Formal parties are spoken of in the plural: there are always multiple formal parties operating simultaneously, each pathfinding according to its own method of dead reckoning and thereby elaborating the pattern or principle in distinct directions that often pull against one another.

No single formal party can ever be said to operate as “the vanguard” of the class as a whole. Nonetheless, just as cresting waves represent a deeper fluid motion beneath, the historical party will always generate its own advance detachments. Any formal party therefore has the potential to serve as one of many vanguards of the historical party. These vanguards often operate along different dimensions: some formal parties express a more advanced and comprehensive theoretical understanding, while others express more refined tactical knowledge, or simply allow their spirit to shine brightly in battle, each brave act igniting a new signal fire to draw the class into its fated combat.

These parties usually emerge from the self-reflexive excess of the event, though they can also appear in intervallic periods in weak forms, particularly when the overall level of partisan subjectivity is high. At root, a formal party comes into being whenever groups of individuals come together to self-consciously expand, intensify, and further universalize an event. Formal parties also often outlive the upsurge of the historical party and, in the intervallic period between social ruptures, may attempt to elaborate the collective truth unveiled by the event, prepare for future uprisings, or (if they have the capacity) intervene back into prevailing conditions to make the emergence of future events more likely and to ensure that they have a higher probability of overcoming earlier limits. In this sense, formal parties express a weak or partial form of subjectivity, or, more accurately, the initial, stuttering process through which a revolutionary subject is gestated.

The vast majority of formal parties are small and practically oriented groupings that have a “tactical” or practical character, commonly emerging out of makeshift functional collectives formed in the midst of some struggle: an organizing committee in a strike wave, the shared kitchen in an occupation, groups of frontliners engaging in riotous confrontations with police, study and research collectives formed to better understand the struggle, or various neighborhood councils that invariably emerge in the midst of an insurrection. But formal parties can also be larger, more explicitly political, and even “strategic” in their orientation, so long as they retain this partisan aspect. Tactical groups that do not dissolve will tend in this direction. As a result, they may even evolve into nominal “communist parties,” each expressed as the communist party of some location and often contrasted to other, overlapping “communist parties.” None, however, is the communist party as such.

Though it sounds like a riddle, formal parties exist whether they acknowledge themselves to exist or not. That is to say, formal parties also describe “informal” groupings that may not think of themselves as coherent “organizations.” For example: groups of friends who come together every night in the midst of the struggle, sub-cultures that participate in the uprising and are subsequently riven by its aftermath, and of course the various “affinity groups” and “informal organizations” that ironically tend to have some of the more rigorous forms of discipline and refined command structures. Regardless of their supposed “informality,” these groups in fact operate according to formalities of custom, charisma, and simple functional inertia.

The difference between “informal” and “formal” groups is not actually whether or not they are formal parties (both are), but the degree to which this formality is an explicit and self-avowed feature of the organization. Similarly, their partisan aspect — the commitment to elaborating the collective truth of the event in general and overcoming the limits of any given event — has nothing to do with their programmatic statements. Formal parties are instead tested, and lose or retain their status as partisan organizations, when confronted with new political events. Such events demonstrate whether that party has retained its fidelity to the communist project, by creating the conditions in which its attitude and behavior can be tested against the “anarchy” unleashed by any given uprising. Does it engage with the new revolt at all? If so, does its form of engagement tend to divert that revolt toward more conservative paths? Or does it serve a practical function helping to push that revolt beyond its limits?

If found to be lacking, the former formal party is reduced: no longer a party at all, but instead a mere organization or, even worse, an operational organ of the party of order, or anti-party. This is one of the reasons that the formal party is always ephemeral. As functional and often happenstance groups, formal parties often self-liquidate when no longer needed, or else change shape, evolving from tightly-knit tactical groups in the midst of an uprising into a more amorphous social scene in its aftermath. Meanwhile, larger organizations often retain the appearance of being a formal party only to completely fail the test of the event itself, at which point they retreat into obscurity, washed away by the tides of history or hardened into nothing but a cultish sect that serves no practical function. By this same logic, preexisting organizations may suddenly take on partisan functions and thereby become formal parties, whether they were explicitly political before the uprising (abolitionist groups, unions, mutual aid societies) or were only marginally political (football ultras, churches, disaster relief organizations).

The “shedding” of ossified formal parties is itself productive, however, since future formal parties then emerge through their opposition to these ossified organs and, in so doing, express more advanced forms of subjectivity. For this reason, freshly liquidated and ossified formal parties form something like the soil structure out of which more complex forms of political life can emerge. Understanding this complexity then requires making more granular distinctions between different forms of organization as such (in particular, the apolitical and pre-political organizations most likely to take on partisan characteristics in the midst of an event, or most useful for partisans to interface with) and between different species of formal party: the purely tactical and happenstance, the “informal” militant group, the “formal” militant group, the radical union, the self-defense militia, the ostensible “people’s army,” the nominal “communist party,” etc.

The atomic form of partisan organization is what I call the “communist conclave.” Communists are produced in the midst of political events, and often emerge alone or, at best, in very small groups. Similarly, communists often find one another in the midst of struggles and begin coordinating in an informal fashion. These small groups of communists can be referred to as “conclaves,” given their private and somewhat ritualistic character, and of course the fact that they are organized in fidelity to a transcendent project. Anywhere that two or three gather as communists there exists a conclave, regardless of whether it thinks of itself as such. Conclaves operate primarily through affinity. Some then elaborate this affinity into more formal divisions of labor or into larger, informal subcultures. Often, conclaves serve as the seed for more elaborate formal parties.

Even when formal partisan projects emerge, however, conclaves persist within and across them. These links of informal affinity are themselves important formal parties. They serve to span the divide between partisan and non-partisan organizations, to more densely integrate formal partisan projects, and to provide resilience and redundancy when formal organizations strain and splinter. In other words, minor formal parties will always exist within the body of more complex formal parties. Informality and formality, spontaneity and mediation, opacity and transparency are not opposed. Neither can be privileged over the other, nor be eliminated in its entirety. Secretive conclaves will (must and should) exist within formal communist organizations with transparent membership, and even more secretive conclaves will exist within the conclave.

Theory, tactical invention, and camaraderie are forged in these dark, intimate spaces before being elaborated in more open venues through transparent discussion, debate, and experimentation. While a conclave may be visible from the outside, it remains a relatively opaque institution. On the one hand, this always poses a threat to the larger organization, insofar as it enables backroom scheming and secretive power-grabs. On the other hand, this privacy is precisely what allows the conclave to be experimental and creative. More complex formal parties must be designed to simultaneously guard against and accommodate the persistence of relatively opaque formal parties within it, and, ideally, to draw on these organs as a source of vitality. Though these conclaves can potentially be integrated into open caucuses or factions within larger organizations, they are not synonymous with them, and are often aligned through happenstance factors (such as shared experience in a struggle) rather than theoretical agreement. They therefore precede this more public caucus work, and a single caucus likely includes multiple conclaves.

The communist party (eternal)

The communist party emerges through the interplay of the historical party and the many formal parties that it generates, encompassing and exceeding both. Eventually, some combination of structural factors causes increased turbulence within the historical party. Meanwhile, the weak or partial subjective force of various formal parties, yoked together by will or circumstance, is eventually able to intervene back into surrounding conditions to further vitalize the historical party that birthed them. The result is an emergent form of organization operating at an entirely different scale than that of either the happenstance upsurges of the historical party or the makeshift, tactical, and largely localized (even if large-scale) activities of the formal parties. The communist party is singular, but multitudinous.

As an expansive environment of increasingly organized partisanship, the communist party is never the name for any particular, official “Communist Party” operating anywhere in the world. Though these many “uppercase” communist parties are often important elements of the “lowercase” communist party, it cannot be reduced to them. Moreover, it is always a major strategic error to attempt to subordinate the communist party as such to the interests of a singular Communist Party (even if this Communist Party has come to represent some local revolutionary upsurge). The communist party is perhaps best thought of as a form of “meta-organization” that both further enables the elaboration of formal parties and further stimulates the vitality of the historical party surging beneath. It is therefore possible to speak of the communist party as a partisan “ecosystem” of sorts, insofar as the interplay of the historical party and the many formal parties rooted in it literally create a partisan territory that then, as medium for subsequent organization, poses its own emergent constraints and incentives.

But this image of the party as “ecosystem” is, in fact, ideological. After all, the ecosystem metaphor is favored in liberal political philosophy because of its allegedly “horizontal” logic, which seems to replicate the (also allegedly “horizontal”) operations of the market. And, in this case, it simply does not capture the entire picture: the communist party is not an ecosystem of struggle blindly sprawling forward in history. It is instead the point at which the weak subjectivity visible in the formal party sublates into a strong subjectivity adequate to the task of revolution. This revolutionary subjectivity necessarily spans individual organizations and is itself organized, intentional, relatively self-aware (though this depends on one’s position within it), and unevenly distributed in its geography and demographics.

The communist party has, traditionally, also been described in the overly loose language of an “international communist movement,” and in the overly narrow language of any given “international,” which is then assigned some ordinal status in the historical sequence. Ultimately, it is best seen as lying somewhere between the amorphousness of an ecosystem or movement and the rigid chapter-like structure of various iterations of the formal, federative internationals. But it is also more expansive than either insofar as its real organizational capacities lie outside of either the broad “communist movement” or the narrow federations of “Communist Parties,” measured instead by their relation to the specific counciliar or deliberative associations that emerge from the class in the midst of an insurrection, and which then begin taking communist measures whether bidden to do so or not, thereby forming the communes that (if they survive) come to serve as the heartland and engine of the revolutionary sequence. Communes can only emerge, however, when the circuit between formal parties and the historical party is well-established, creating a subjective environment in which deliberative, expropriative, and transformative forms of free association become an organic outgrowth of class activity.

Like the event, the communist party can emerge, fall into eclipse, and then reemerge at a later time — but it is always the same communist party, tied with a red thread to its earlier instantiations. Its extensive (geographic, demographic) and intensive (organizational, theoretical, spiritual) growth is itself the wave of revolution that initiates the process of communist construction. Similarly, like the formal party, the communist party can appear to ossify, to fall into disrepair, and to abandon its fidelity to the communist project, as when the social democratic parties of the Second International devolved into reformist statecraft and warmaking. In such a situation, however, the communist party is not actually ossifying but is instead being eclipsed. Such an eclipse can be caused by any number of factors, but it is always signaled by the failure of the formal parties that once composed the communist party to retain their fidelity to the communist project. For this reason, the explosive reemergence of the communist party is often elaborated against these ossified remnants, as when the Third International emerged from a series of mutinies, insurrections, and revolutions that initially sought to emulate the party-building of the Second International and was forced, in the end, to elaborate itself in opposition to this very inheritance.

The communist party has long been in a period of eclipse and, though signs point to its reemergence, it cannot yet be said to exist in any substantial form. Again: the party as such is not merely the sum of “leftist” activity at any given moment, but instead a form of supra-subjectivity that subsists only in the incendiary confrontation with the prevailing social world, serving as the passage through which communism can be elaborated as a practical reality. Rather than the senseless aggregation of many minor interests into a complex system, then, the communist party represents the materialized flourishing of human reason necessary for the species to self-consciously administer its own social structure, which is simultaneously its social metabolism with the non-human world.11 This is why we can speak of the communist party as the social brain of the partisan project, and even as the gestation chamber of communist society itself.

The communist party is therefore eternal, in the sense that it is the larval form of an immortal body: the bloom of reason and passion across a self-aware species consciously coordinating its own activity as a geospheric system.12 In other words, the communist party is the only weapon capable of truly destroying class society — nullifying the eons-old struggle between simple egalitarianism and social domination by subsuming both under a higher principle of prosperity — and is also, through this very destruction, the vehicle through which the truth unveiled by the historical party and elaborated by the multitude of formal parties blossoms into an entirely new era of material existence underpinning a rational social metabolism at the planetary scale.

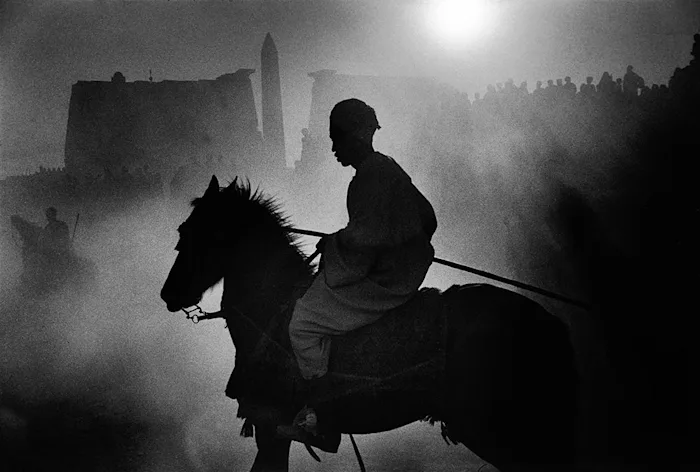

Images: René Burri

Notes

1. For a similar critique of this approach, applied to a concrete example, see: Jasper Bernes, “What Was to Be Done? Protest and Revolution in the 2010s,” The Brooklyn Rail, June 2024. Online here.↰

2. Perhaps more telling is the question of why, even when these individuals and their affiliated organizations have ostensibly “gained power” through elections in the wake of the revolt (as in the cases of Syriza, Podemos, or the Boric government in Chile), they have then completely failed to enact any meaningful social change. In fact, the diversion of popular revolt into electoral campaigns has almost universally served as a suppressive force, helping to disintegrate the meager forms of proletarian power that were emerging outside the institutional sphere. This occurs regardless of political predilection, or the intent of any individual leaders. ↰

3. For an overview of the idea, see: David Kilcullen, Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerrilla, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015, p.124-127↰

4. The concept of the “sigil” is an elaboration of the “meme with force” developed by Paul Torino and Adrian Wohlleben in their article “Memes with Force: Lessons from the Yellow Vests” (Mute Magazine, February 26, 2019; online here), and further expanded in Adrian Wohlleben, “Memes without End,” Ill Will, May 17, 2021 (online here).↰

5. The use of an example drawn from the right is not coincidental here, as right wing organizations have proven particularly adept at deploying this logic over the past several decades. One reason for the ascent of the right is precisely because this sort of leadership is often refused outright by those on “the left,” who treat it as an inherently authoritarian imposition on the spontaneous momentum of the class, rather than a self-reflexive dynamic produced through that very momentum. The fleeting moment is thereby lost, and the sigils are left to burn out on their own. I explore the ramifications of this problem for politics in the US in Hinterland: America’s New Landscape of Class and Conflict (Reaktion, 2018) and examine the same conundrum in Hong Kong in Chapters 6 and 7 of Hellworld: The Human Species and the Planetary Factory (Brill, 2025).↰

6. The partisan project refers to ongoing attempts to organize some form of collective revolutionary subjectivity oriented toward communist ends. In other words, it references both the past and the future of the struggle to emancipate humanity from the historic fetters of class society and inaugurate a communist future. It is therefore loosely synonymous with “communist organizing” or the “communist movement.”↰

7. Even within mass political uprisings that exceed the bounds of subsistence expressed in the form of concrete interests, a tension nonetheless persists between this excess and its expressive grounds. Exploiting this tension in favor of the expressive is how these political ruptures are suppressed and reabsorbed into the status quo.↰

8. Marx speaks of the “party of Anarchy” and “party of Order” in a set of articles written for the Neue Rheinische Zeitung in 1850, which would later be compiled into a book, Class Struggles in France: 1848-1850, by Engels in 1895 (online here). In this book version, the terms appear in Chapter 3. The same terms reappear in subsequent works, such as the 1852 Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. The “anti-party” is my own addition, introduced in Hinterland (selections available here). ↰

9. This theoretical framework is drawn from the work of political philosopher Michael Neocosmos. See his Thinking Freedom in Africa: Toward a Theory of Emancipatory Politics, Wits University Press, 2016.↰

10. Nonetheless, the simultaneously universal and aleatory nature of the event also means that this reshuffling of coordinates remains difficult to describe. For example, it is clear to basically any observer that “everything has changed” after the George Floyd rebellion, and yet all of us would be hard-pressed to explain exactly how things have changed, or to point to any single case.↰

11. For further elaboration on this idea, see: Phil A. Neel and Nick Chavez, “Forest and Factory: The Science and Fiction of Communism,” Endnotes, 2023. Online here.↰

12. More rigorously: the self-actualization of the “species” as subject, beyond its status as an apparent biological fact which in fact expresses the material unity of human productive activity in capitalist society. This is the realization, in practice, of what Soviet geologist Vladimir Vernadsky (popularizer of the term “biosphere”) once speculatively referred to as the “noosphere.” The idea is explored in more detail in Neel, Hellworld, Chapter 2.↰