Through the Looking Glass

Serene Richards

It is often said that the Spectacle, as the form of power proper to contemporary capitalist society, expropriates our powers of language and imagination only to return them to us as alien and hostile forces. But what in fact are these capacities, such that they could be stolen from us in the first place? When we think, imagine, and perceive, is this an individual act or event? Is it possible to think with others, to genuinely see something in common? In the following excerpt from her new book, Biopolitics as a System of Thought (Bloomsbury 2024), philosopher Serene Richards turns to medieval Arab philosophies of the imagination in order to recover a form of thinking she terms the “material intellect.” Such intellection or “phantasm” (as Averroës termed it) is bodily not mental, and moves not by ascending to universals but from particular to particular through an intermediary realm between self and world, individual and collective, using images and memories as its vehicle. Its political import, according to Richards, derives from the fact that, unlike our private thoughts or feelings, the phantasm can never become the property or claim of a specific person or individual. Although we always have our own intelligence, the “material intellect” of the phantasm is generic, meaning that it is shared and accessible to all. Mobilizing a minor lineage of thinkers from Dante and Agamben to Fernand Deligny, Pierre Legendre, and Chiara Bottici, Richards shows how the metaphysical operation of the Spectacle consists in occupying and pacifying our imaginal constitution. Yet today, as the mythic origins that once nourished the illusion of political stability wither, leaving nothing but the hollow certainties of technicity, we find ourselves delivered over once again to the abyssal community of our own imaginal life. A new opportunity therefore arises to reclaim phantasmic thought as a “conjoining” of the common and singular, to weave our use-of-self into a collectivity of thought, or what some have called a form-of-life. What Richards is after is nothing less than the philosophical basis of a destituent communism to come, the point of departure for which she claims must be located in our sensible contact with the world. As she writes, “if the stakes of our ‘sensory apprehension of thought’ are high, this is because it is living itself that is in question.”

To phantasm

What happens to a word or concept that falls out of use? Its banishment or forgetting, like the smoke we see linger long after a candle’s flame is extinguished, persists, patiently awaiting the time of its recollection or reconstitution. The word that we have in mind here and that has long ago fallen out of usage is the word “cogitare,” cogitate. Cogitare is not the same thing as “think.” When referring to the act of the intellect, medievalists use the verb “intelligere.” Cogitare is something different. As Jean-Baptiste Brenet writes, first, it is not a fact of the intellect even if it can only be effectuated in its presence. It is an operation of the soul in its body. Secondly, cogitation, unlike intellection, does not have universal notions as its object. It moves from particulars, it proceeds from the animated body’s encounters, sensations, with beings of the external world, of their traces and imprints — their images and their phantasms. Brenet sums it up thus: “I cogitate means: I phantasm.”1 Medieval Arab philosophers posed this question, inheriting the Greek dianoia and thinkers of a new psychism where the brain is not the center or site of intelligence or of reason, but became so only through images. Through the idea of fikr, possibilities and virtues were situated in this sort of intermediary realm as though the real world was in play in it. As Brenet writes: “this third middle state is composed of floating representations, neither sensed nor conceived, such that man, before being reasonable, was a cogitating animal by way of its proper phantasms."2 Averroës (Ibn Rushd, ابن رشد) develops this idea further, joining the imagination to his doctrine on the intellect. For Averroës, cogitation involves a continual movement between images and memories. Importantly:

This power of phantasms is ordered by an intellect distinguished by four extreme features: its substantial separation from bodies, its absolute uniqueness, its eternity, and the originary emptiness of its nature, since it is from the beginning pure potentiality. It is in the space opened up by this decentred, unique and omnitemporal mental power that Averroës situates the mediating work of cogitation.3

This notion of a third space, where cogitation takes place by way of the phantasms, is unknown in modernity for whom everything comes from the subject; the potential of the phantasm is erased. A forgetting then of the necessary link between the imagination and the intellect even if, though expelled from the subject, it lingers all around it, notably in dreams, where the phantasm still lurks. In De Insomniis [On Dreams], for example, Aristotle describes the dream as a kind of phantasm, belonging to the sense-perceptive part of the soul.4 Agamben refers to “Roman de la rose” to illustrate this point, an allegorical dream vision where the protagonist’s dream provides him with a certain knowledge he would not otherwise have acquired without it, just as the Mohave community, indigenous to the Colorado River, believed that knowledge of myth and skills could only be acquired in dreams. To such an extent that anything learnt in a state of being awake remained redundant unless this knowledge was also dreamt. As the anthropologist George Devereux says: “[A]fter allowing me to record his ritual curing songs, a shaman explained that this would not enable me to cure people by singing these songs, because I had not ‘potentiated’ them by learning them also in dream.”5 Devereux notes that those songs and myths that are dreamt are so long and detailed, that they would pose great difficulties to psychotherapists seeking to interpret or analyze them. This is because, as Emanuele Coccia tells us, “dreaming, in fact, means first and foremost to imagine; the image is not just a simple psychic object here, but is in effect the matter or the life from which everything is made and everything is nourished.”6 That is, it is not a matter of simple cognition to be interpreted, but of a coincidence with the medium of knowing, “we are made of the same matter as the images that give body and consistency to our desires and our fears, and we have a body which is defined by its sole capacity to be and to become what we are able to imagine.”7

Agamben traces the notion of the phantasm to Plato’s Philebus and a dialogue between Socrates and Protachus, concerning the relation between memory, the senses, and truth. A question arises as to where, in the mind, does a painter draw up images of things said, and how does this take place? To this, Socrates answers: “When a man, after having received from the sight or from some other sense the objects of opinion and discourse, sees within himself in some way the images of these objects.”8 This artist of the mind, Agamben writes, who draws the images of things in the soul is what is called the “phantasy,” and these images or pictures are defined as phantasms. For Plato, desire and pleasure are impossible without phantasy: a corporeal pleasure, isolated from any other senses or passions, does not exist. Moreover, according to Aristotle, there can be no memory without phantasm; as such, it forms the necessary condition of both intellection and cognition. This mode of thought is foreign to us, Agamben writes, “perhaps because of our habit of stressing the rational and abstract aspect of the cognitive process,” and because of this, we “have long ceased to be amazed by the mysterious power of the internal imagination, of this restless crowd of ‘metics’ (as Freud would call them) that animates our dreams and dominates our waking moments more than we are perhaps willing to admit.”9 For Averroës, the eye is a mirror where the phantasms are reflected; as a mirror, it must first be illuminated in order for the images to be reflected — the air reflects the “water” of the eye. The eyes and sense are the mirror and water that each reflect the form of the object; in Averroës, phantasy is also speculation which can “imagine” the phantasms without objects.

As the point of union between the individual and the unique possible intellect, Averroës’ conception of the phantasm became the subject of much controversy in the thirteenth century. For Averroës, the intelligence is something that is both unique and supra-individual of which individual persons simply had the shared use. As he writes, “the possible intellect is unique and separate: incorruptible and eternal, it is nevertheless joined [copulatur] to individuals, so that each of them may concretely exercise the act of intellection through the phantasms that are located in internal sense.”10 The image (reflected in phantasy) represents our union with the supra-sensible, and is situated at the limit between the individual and the universal, corporeal and incorporeal. The material intellect described by Averroës is a power and receiver of thoughts; while there is one intellect for each human being, the material intellect is shared. We have our own intelligence, but only one shared intellect that is accessible to all. By “one” Averroës does not mean an identifiable person like God, for example, but a power, a human power to think. This power is common and not individualizable, and can only be made use of through phantasms or images. Beyond a mere mediating function, the phantasm names our common power to think, our material intellect.

This idea of a communal or collective intellect is also found in Dante’s Monarchia, which draws heavily from Averroës’ conceptualization of the material intellect. The specific power of humanity, Dante writes, is to think the potentia sive virtus intellectiva. Unlike God and the angels who think in act, the human being has the possibility of thinking, the potential or power to think, such that what is proper to man is the possible intellect. As Brenet writes, “If [for Dante] the power of human beings as such is intellectuality in potential, its essential operation can only be to activate it, and indeed to actualize it in its entirety simultaneously and all the time, without which a power would exist separate from its act.”11 In this remarkable formulation we can recognize Spinoza’s conceptualization of essence as power, as already being power, so that there is a perfect coincidence between essence and existence, potential and act. How is this feasible? For Dante, it is only feasible through the multitude: it would be impossible for a single person to entirely and simultaneously put into act this intellectual power, or even for a particular community or village; as such, it falls to the multitude. Intellection is never a private, individual affair, it can only be realized in common: this is the meaning of the phrase “people think.” There is only a multitude because each one carries within themselves a power. For this reason, Agamben writes: “I call thought the nexus that constitutes the forms of life in an inseparable context as form-of-life. I do not mean by this the individual exercise of an organ or of a psychic faculty, but rather an experience, an experimentum that has as its object the potential character of life and of human intelligence.”12 This is the experimentum crucis of Averroism: the phantasm conjoins [copulatio] the single material intellect and singular individuals.13 Thinking, for Agamben, is not simply being affected by this or that thing but also and at the same time being affected by one’s own receptivity, such that “thought is, in this sense, always use of oneself, always entails the affection that one receives insofar as one is in contact with a determinate body.”14 In this way, just as for Averroës, Dante, and Spinoza, so too for Agamben the act can never be fully separated from a power or potential: if there is thought, then a form of life can become form-of-life. The decisive point is that this experience of thought can only ever take place as common use and potential. There is a multitude because “there is in singular human beings a potential — that is, a possibility — to think.”15 Moreover, the existence of the multitude is immediately political since it renders inoperative the apparatus that divides life into specific functions, values, and uses. This apparatus — the inscription of the ontological machine — cannot comprehend the conjunction of essence and existence but can only know and govern its separability, as something not-yet to be realized, thereby condemning those it governs to absolute privation and abandonment.

Through the looking glass

Ours is the age of the infinite proliferation of images. From our so-called public spaces to the devices we carry with us, in every corner of the spaces we move through and inhabit, we are everywhere saturated with disembodied images of which we might not know the context or the significance. These images mediate and saturate our thoughts, filling them with injunctions and injustices, disasters, war, poverty, and a looming extinction in the face of which we remain immobile. We circulate and exchange these same images with each other in the hopes that somewhere, somehow, someone will do something. By and large, we remain spectators of our own immobility and suffering. This is not to say that acts of sabotage and resistance to injustices do not take place. Indeed 2019 saw a massive explosion of mobilized anger. Everywhere from Baghdad to Santiago, from Paris and Harare to Beirut, Manila, and Tehran, people mobilized to bring down leaders, as in Lebanon and Iraq, elsewhere gaining assurances with promises of reform. Yet their suffering and despair remains, along with their growing disillusionment, entrenched loneliness, famine, and exhaustion. While mass impoverishment deepens, the number of new billionaires is the greatest since records began, testifying to an unprecedented transfer of wealth, a heist in broad daylight, a bonanza of the unhinged with war, misery, and impotence as its constants.

Such is the cruelty of the spectacle, “the very heart of society’s real unreality,” which ensures a “permanent presence” aimed at justifying the conditions and aims of current social relations.16 At once the dominant mode of production, it also governs our time spent outside this production process, all the while being informally part of it: under the injunction to belong and to be social, we participate in it as passive recipients of its signs and models. The spectacle presents itself as a vast inaccessible reality that can never be questioned. Its sole message is: “What appears is good; what is good appears.”17 The passive acceptance it demands is already effectively imposed through its monopoly over appearances, its manner of appearing without allowing any reply.18 There is no creative act in the spectacle; as an imposed mode of appearance, the latter is “what must be seen but can never be lived.”19 The cruelty of the spectacle ignores our relation to the image and sensibility, what Pierre Legendre describes through the trilogy body-image-world. Between the self and the world, the potency of imagination tames the void, the abyss in which we dwell. As Legendre writes: “it is not as if there were the world of things and us; rather there is a generalized theatricization of man and the world.”20 Yet with our bodily sensibilities detached from the images, and the capacity to inhabit them eternally postponed, loneliness becomes a generalized disposition. This loneliness differs in kind and in form from that fecund solitude where thought can take place and the imagination flows. As Arendt reminds us, even in solitude we will eventually need the presence, solace, of other people, since

…the only capacity of the human mind that needs neither the self nor the other nor the world in order to function safely, and which is as independent of experience as it is of thinking, is the ability of logical reasoning, whose premise is the self-evident. The elementary rules of cogent evidence, the truism that two and two equals four, cannot be perverted even under the conditions of absolute loneliness.21

A kind of strict self-evident logicality has taken hold of us, which leaves us incapable of saying anything about the world. This is the trouble with the spectacle: the expropriation of images and experience, of language and world, has left us with a cold determinism and boring causality that is neither inspiring nor comforting. To cover over the abyssal void of origins, the metaphysical tradition of the West requires the presupposition of a ground. In a short intervention entitled Before the Abyss, Jean-Luc Nancy writes that, “Since what is called ‘the death of God,’ we — Occidentals or Western-planetary civilization — are before an abyss… For the ‘God’ that ‘died’ was nothing other than the ground itself.”22 This so-called loss of ground leaves us face-to-face with the abyss that, since the beginning of the beginning, we have strived to cover over and fill with meaning in the hopes of providing answers to the “why” of life and living, filling it with stories and myths, images and emblems that would serve as our reasons for living, making life itself worth living. Nancy observes that, today, explanations are offered that, while providing a series of facts concerning this or that phenomenon, end up saying very little:

Today, for example, one can read in a magazine: why do we experience arousals [Erregnung] — joyful and sorrowful? And then, there follows a neuroscientific explanation of the brain, neurons, nerves, etc. But with this, we don’t get to arousal itself. Through this science we receive knowledge about causalities that have nothing to do with fear, joy, fun, or discontent.23

Nothing, then, to do with life and its manifold expressions, emotions, tonalities, affective possibilities and eternal contradictions. While the dominance of the sciences of ultra-modernity is new, a proximity to the abyss has characterized the human condition since long before the “death of God” in the seventeenth century. As the human being is the being without essence, answers to its “what” and “why” have always been sought and fabricated. For Legendre, this is the characteristic function of the syntagma vitam instituere, or instituting life.24 To institute, Legendre says, is “to establish, construct, in such a way that it holds up.”25 Referring to Vitruve, a well-known architect from the first century, Legendre adds a crucial caveat: it is not enough for what is constructed or built to hold up, it must also have the appearance of being upright, the appearance of solidity. In other words, Legendre says, what is held up is underpinned by a projected image — a mise en scène. Nothing captures the essential fragility of this appearance, and its disappearance, better than Magritte’s La Lunette d’approche (1963). It is not for nothing that Legendre says that all the images, mirrors, and emblems evoke the ungraspable. Yet the human being ceaselessly interrogates these ungraspable, ephemeral representations. “We fabricate,” Legendre says, “what Magritte calls the Looking Glass.” We see a window left half open:

The shutter that opens takes the landscape with it, the clouds and the sky. The looking glass discovers what lies behind the emblems, the images, the mirrors: a void, a chasm, the Abyss of human existence. It is this Abyss that we must inhabit. A reason to live begins here.26

The seductive abyss draws us into its emptiness, an abyss that we are compelled to gaze into, manipulate, and make our own. From images to myths, emblems, and slogans, the collectivity of thought fills the void and renders it meaningful. Gods in mirrors reflecting what we wish to see, a final answer to the “pourquoi?” being too tempting to forego. And so we go setting beginning after beginning, foundation after foundation. That we dwell in the dogmatic has long been forgotten; technicity, having shunned the mythologemes characteristic of the foundation and ground, now proffers its certainties as origins. That the enigmatic always plays a role in our encounters is denied shows, Legendre argues, that the aim is no longer “an analysis of the human condition, but the legal realization of the government of subjects.”27 As Fred Moten and Stefano Harney write in The Undercommons:

Governance is an instrumentalization of policy, a set of protocols of deputization, where one simultaneously auctions and bids on oneself, where the public and the private submit themselves to post-Fordist production. Governance is the harvesting of the means of social reproduction but it appears as the acts of will, and therefore as the death drive, of the harvested.28

Our modern culture has forgotten its imaginal constitution, and yet the uncertain persists as the shadow of language and the unthought: phantasms and dreams that we are incapable of interpreting — but precisely for this reason tell us something — all this necessarily accompanies our discursive, textual, and evidential certainties. While metaphysics has been preoccupied with the presupposition of foundations as conceptual truths, by inadvertently shutting out the imaginal as their very condition of possibility, it brings forth, conjures up, the possibility of its own foreclosure. From the beginning, what has been in question for us is how to “metabolize” that which for the human condition is precisely impossible to assume, assimilate or represent, i.e., the abyss, and our shared relation to nothingness.29 If there is to be a universal law that could be said to bind societies the world over, it lies in our shared dependence upon the sensible for crafting an art of living, for the organization of social life, from government to officio and form-of-life. This law, Legendre tells us, stems from our encounter with the abyss — the lack of ground or foundation that irreparably envelops all human beings. It is only through the experience of the sensible that any sense as such can subsequently emerge, be thought, or constructed and reconstructed anew. If the stakes of our “sensory apprehension of thought” are high, this is because it is living itself that is in question. This anthropology of the sensible, as Coccia has called it, is not merely a question of cognitively intuiting the meaning of images put forth before us as living beings with so-called sensory faculties. Rather, “the image and the sensible give body to activities of the spirit and give life to man’s own body.”30 It is an exercise in proximity, relation, perception of and to the image, that brings the spirit to life. The human being can only live through this mediation. More than a faculty, what is in question is the imaginalis, which, as Chiara Bottici explains, is an adjective “used to characterize a mundus, a world in itself. It is within this intermediate world — neither material, like the world of pure sensibility, nor immaterial, like that of the intellect” that the imaginal operates.31 Moreover, “the imaginal comes before the distinction between ‘real’ and ‘fictitious.’”32 More than representation or mirroring, reality and unreality, the imaginal is always an act of creation. In the spectacle, the trilogy image-body-world is effaced. The image is isolated; the body, as the site of politics, can only receive the image in its representative form, without reply and without world, a stunting of the act of creation. Our present condition is a testament to the consequences of the trilogy’s apparent dissolution, a ceaseless confrontation with images that can only be seen, exchanged, and presented but not lived. Yet despite itself, the imaginal persists, irrespective of our willingness to perceive it or not. This is the quality of the objective unconscious that Coccia alludes to, akin to a medial space that exists externally to us.

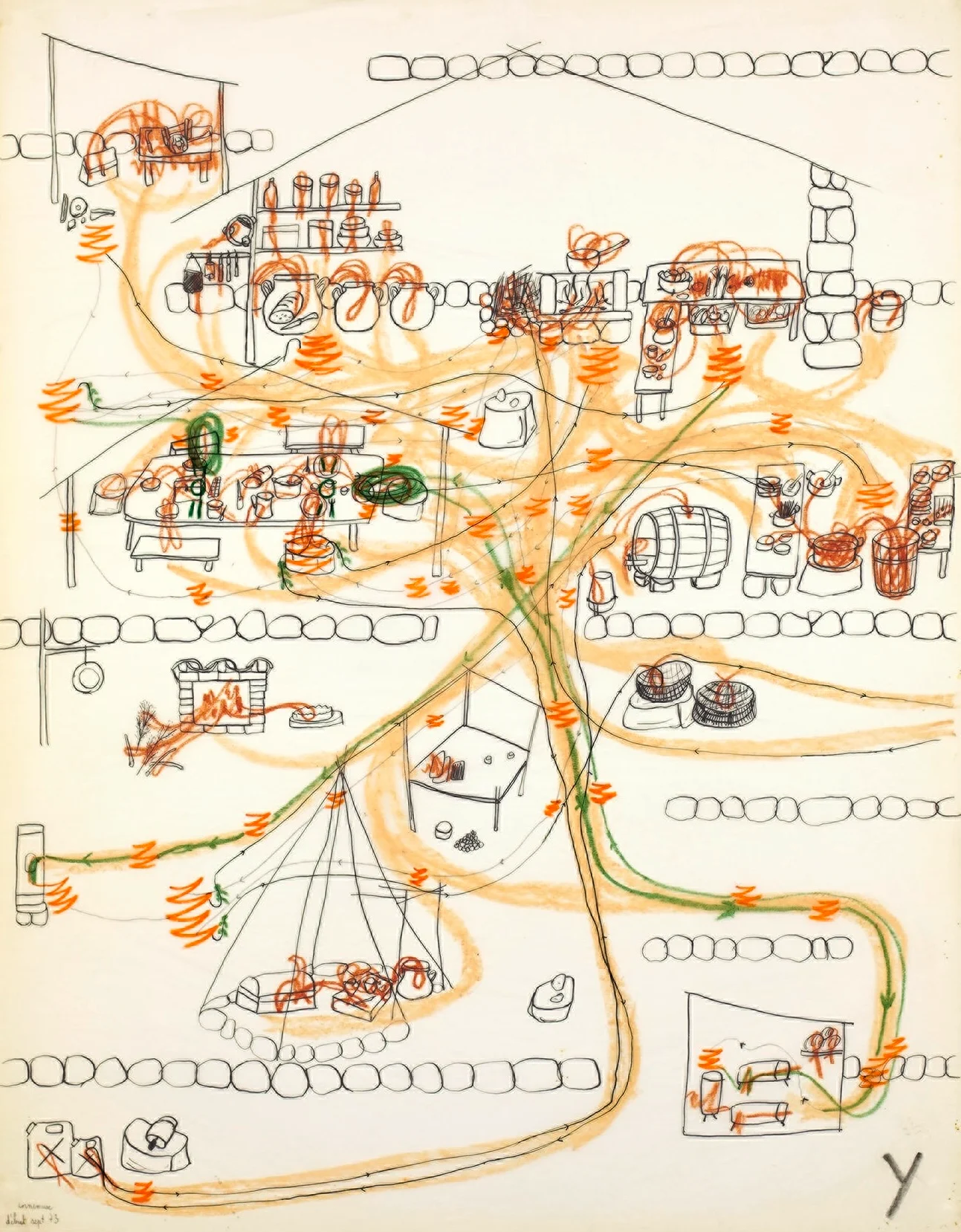

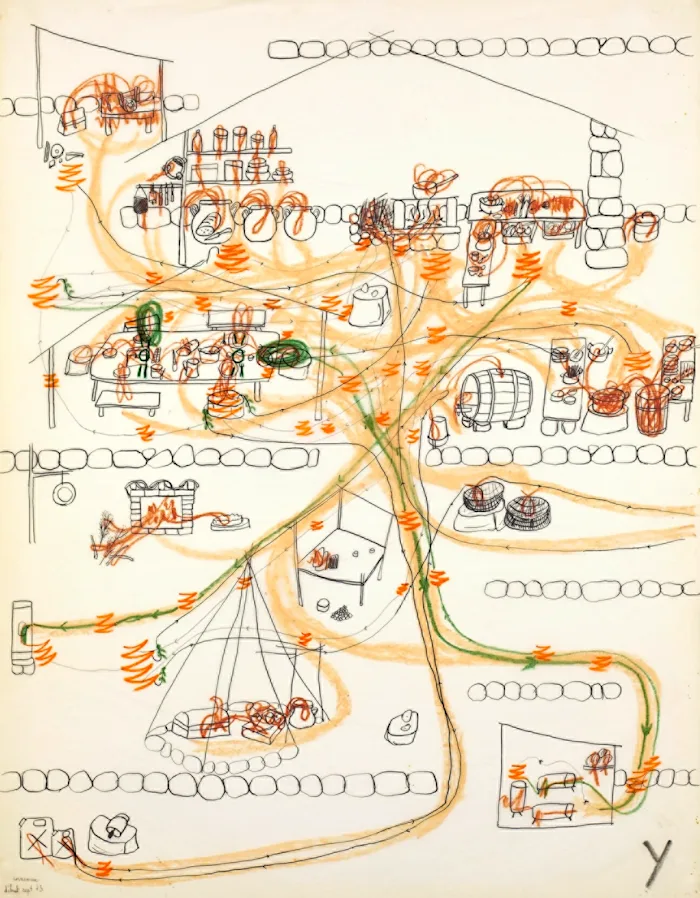

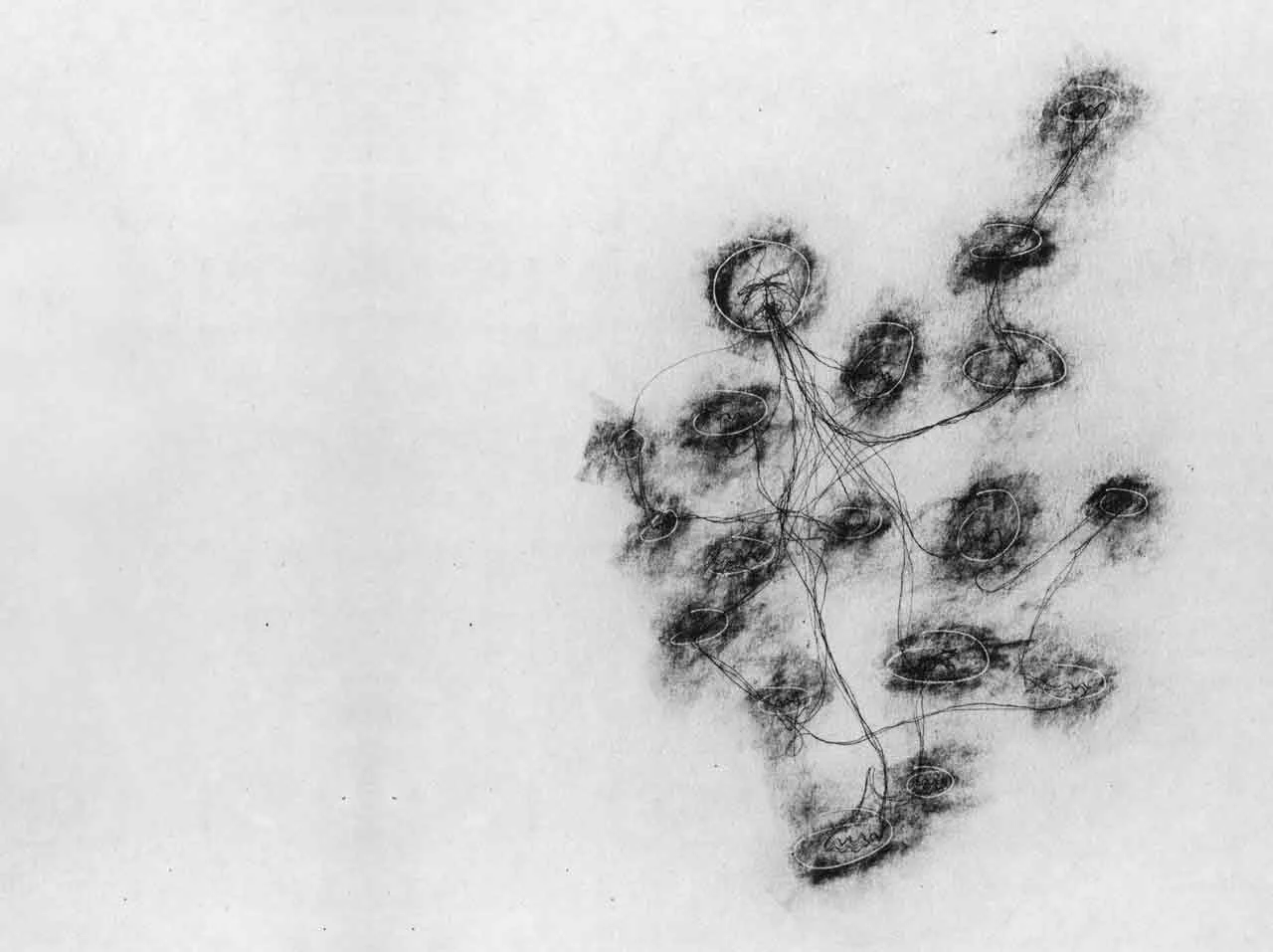

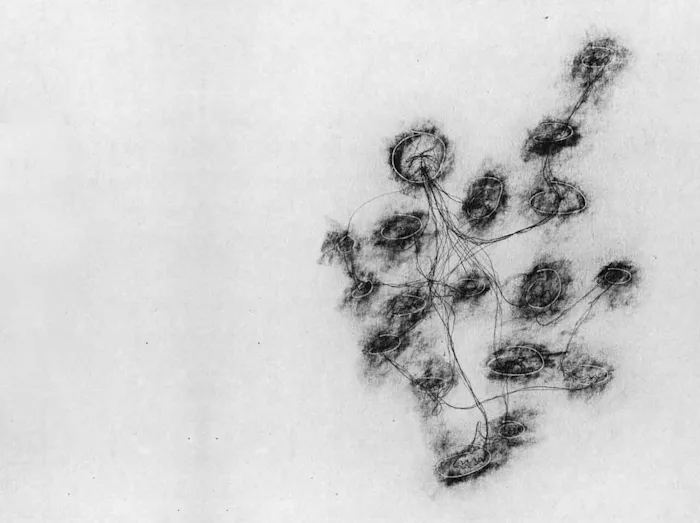

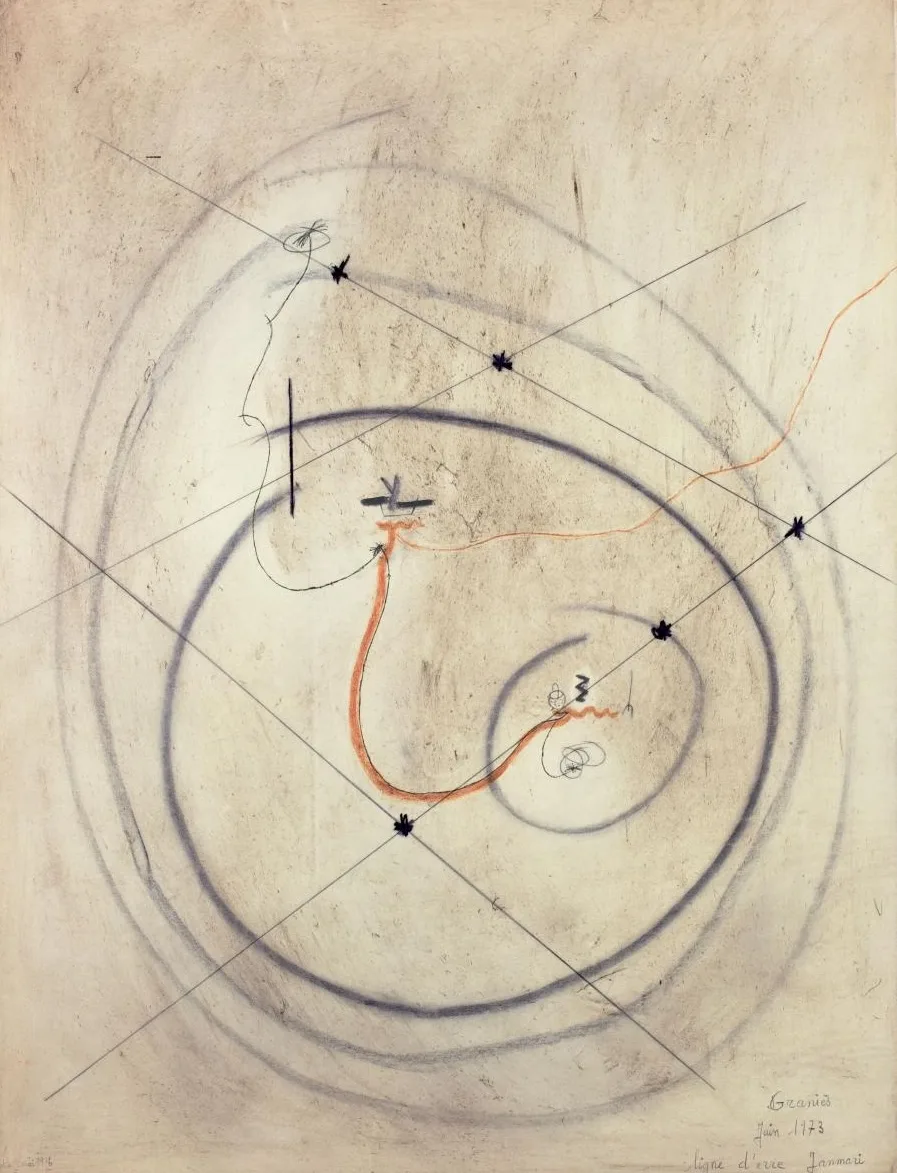

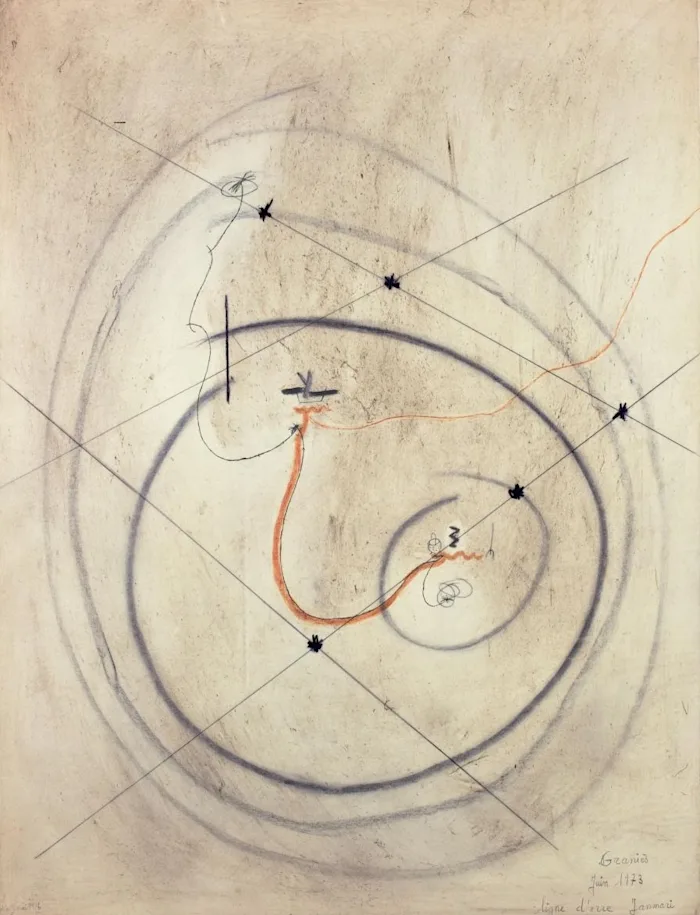

What fills the abyss is not permanent, though it has the appearance of holding up; it can be imagined and made otherwise. There is no reason why this world might not be other than it is. This affirmation should not be mistaken for a return to an ideal past, but rather as a reminder of the impermanence and fragility that envelops us. Clouded by the apparently unshakeable solidity of the institutions that dominate and exploit us, we forget that enigma and the uncertain are always already present here and now. The leap of faith required to construct an unknown horizon is already taken in treading the familiar path, that is, in our familiar world that is itself structurally underpinned by instability and fragility. The void, the abyss, is always shared in common, and in whose void we continually glance even if we do not speak of it out loud. When Fernand Deligny wrote about his experiences working with autistic children, who were believed to exist entirely outside of language and symbolic reference, a lesson emerged from our eternal concern with the “why?” The cartographic drawings of the Lignes d’erre, or lines of errancy, attest to an altogether different relation to the world, a mode of existence specific to the singularity and context of each person living in common with one another. The tracings do not denote a history of the majority, nor a territory, but rather a cartography of life engendered in living. Going beyond the name, the traces exude life, the gestures of daily life. For Deligny, this makes possible a common space for those who speak and those who either do not speak or no longer speak, testifying to the uncertainty of our contemporary representations, its ground always in a process of dissolution. “What does Lacan say?” Deligny asks, “That the one who would take the door as something real would carry it under his arm in order to produce air currents in the desert.”33 It will be for us to see that while the door appears to be closed, it can be picked up and put to a different use, to generate drafts in the desert, to pull apart all that appears as immovable, as a protective screen. To learn to live again, although this time “without why,” without telos, goal or aim.34

Biopolitics as a System of Thought is out now with Bloomsbury. A recent interview with the author can be found here.

Images: Fernand Deligny, Jacques Lin, Le réseau d’accueil d’enfants autistes, et al.

Notes

1. Jean-Baptiste Brenet, Je fantasme: Averroès et l’espace potentiel, Éditions Verdier, 2017, 10.↰

2. Brenet, Je fantasme, 11.↰

3. Brenet, Je fantasme, 12.↰

4. Aristotle, De Insomniis, in The Parva Naturalia, ed. J. I. Beare, The Clarendon Press, 1908, 459a, 94.↰

5. George Devereux, “Dream Learning and Individual Ritual Differences in Mohave Shamanism,” American Anthropologist, New Series 59, no.6 (December 1957): 1036.↰

6. Emanuele Coccia, Sensible Life: A Micro-ontology of the Image, trans. Scott Alan Stuart, Fordham University Press, 2016, 65.↰

7. Emmanuel Coccia, Sensible Life. A Micro-ontology of the Image, translated by Scott Alan Stuart, Fordham, 2016, 65–66.↰

8. Giorgio Agamben, Stanzas. Word and Phantasm in Western Culture, translated by Ronald Martinez, Minnesota, 1993, 73.↰

9. Agamben, Stanzas, 77.↰

10. Agamben, Stanzas, 83.↰

11. Brenet, Je fantasme, 83.↰

12. Agamben, Means Without End, translated by Vincenzo Binetti and Cesare Casarino, Minnesota, 2000, 9.↰

13. Agamben, “Intelletto d’amore,” in Intellect d’amour, ed. Giorgio Agamben and Jean-Baptiste Brenet, Éditions Verdier, 2018, 25.↰

14. Agamben, Use of Bodies, 210.↰

15. Agamben, Use of Bodies, 212.↰

16. Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, Zone Books, 13.↰

17. Debord, Society of the Spectacle, 15.↰

18. Debord, Society of the Spectacle, 4.↰

19. Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, “The Premonition of Guy Debord.” Online here.↰

20. Pierre Legendre, “The Dogmatic Value of Aesthetics,” Parallax 14, no. 4 (2008): 10–17, 11.↰

21. Hannah Arendt, “Ideology and Terror: A Novel Form of Government,” The Review of Politics 15, no. 3 (July 1953): 303–27, 325–6.↰

22. Jean-Luc Nancy, Before the Abyss, April 2021. Online here.↰

23. Nancy, Before the Abyss.↰

24. For a detailed exposition of this phrase and how it relates to Legendre’s work more broadly, see Peter Goodrich and Serene Richards, “L’Empreinte juridique,” in Introductions à l’Oeuvre de Pierre Legendre, ed. Katrin Becker and Pierre Musso, Éditions Manucius, 2023.↰

25. Pierre Legendre, L’Inexploré: Conférence à l’École nationale des chartes, Ars Dogmatica Éditions, 2020, 1.↰

26. Pierre Legendre, Fabrique de l’Homme Occidental, Éditions Mille et une Nuits, 1997, 12.↰

27. Pierre Legendre, “The Masters of Law: A Study of the Dogmatic Function,” in Law and the Unconscious: A Legendre Reader, ed. Peter Goodrich, translated by Peter Goodrich with Alain Pottage and Anton Schütz, Palgrave Macmillan, 1997, 107.↰

28. Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study, Minor Compositions, 2013, 80.↰

29. Pierre Legendre, Dieu au Miroir: Étude sur l’institution des images, Fayard, 1994, 121.↰

30. Coccia, Sensible Life, 5.↰

31. Chiara Bottici, Imaginal Politics: Images Beyond Imagination and the Imaginary, Columbia University Press, 2014, 55.↰

32. Bottici, Imaginal Politics, 56.↰

33. Fernand Deligny, The Arachnean and Other Texts, translated by Drew S. Burk and Catherine Porter, Univocal, 2015, 209.↰

34. Reiner Schürmann, “‘What Must I Do?’ at the End of Metaphysics: Ethical Norms and the Hypothesis of a Historical Closure,” republished in Tomorrow the Manifold. Essays on Foucault, Anarchy, and the Singularization to Come, edited by Malte Fabian Rauch and Nicolas Schneider, Diaphanes, 2019. ↰