What Are Militants?

Steve Wright

Preface

Nobody wants to work anymore. Everyone knows it, many are talking about it, but most are missing the point. Twitter is awash in photos of signs scrawled in black marker on printer paper and taped to doors across the country as managers and business owners bemoan their apparent inability to attract or retain workers. In the US, over 4 million people voluntarily left their jobs in August 2021 alone, and October saw over 100,000 workers from widely divergent sectors on strike. Meanwhile, an anti-work online forum has seen exponential growth in subscribers, from under 50k in October of 2019 to fully doubling in one month from 450k to nearly a million between September and October 2021.

Refusal is in the air. Workers in the US, faced with COVID’s persistent memento mori, are reevaluating how they relate to work in a more fundamental way than they have in decades. In the midst of such a reevaluation, questions about both the desired effects of political practice and about the constitutive forces of revolutionary subjectivity are once again returning to the fore as billionaires race for the stars while plural crises propagate across the planet.

The worker has been the sine qua none of revolutionary struggle for nearly two centuries. As the centrality of the worker (narrowly construed) wanes, we find ourselves again returning to theoretical traditions that have always questioned the assumption that the workplaces and the workers within will bring forth the end of class society.

As this mass defection plays out alongside a widespread romanticization of union efforts, we have yet to see a substantive reanimation of the organized labor movement nor a renewed interest in official political forms. This affords us an opportunity to reflect on the desires driving this trend and the general inability of these movements to adequately respond to them. Does this moment of refusal point toward a more general abandonment of the left’s traditional reservoirs of social and political power? What would it mean to see this generalized refusal as a repudiation of the view that control over labor-power and political representation are the twin horizons towards which political movements must advance? Where can inspiration be found if not in the meeting halls of organized labor and party politics? As workplaces and media landscapes rapidly disintegrate, reform, only to disintegrate again, the Autonomist theoretical tradition can help us better understand and intervene in the relations of production and forces of subjectivation.

Steve Wright's Storming Heaven remains one of the most influential English-language engagements with the theory and history of Italian Autonomist Marxism, a tendency that operated within and against organized labor and the party-form in Italy beginning in the 1960s. When it was released nearly twenty years ago (2002), 9/11’s world-historical impacts were just beginning to be felt, and the transformation of the world’s media landscape had only recently gotten underway. In the book, Wright provides an overview of “workerism” by examining the thought of a select number of the tendency’s main intellectual figures, including Antonio Negri, Mario Tronti and Sergio Bologna. These thinkers wanted to more directly engage a latent antagonism between workers and militants, an antagonism over the very horizon of political desire. The desire for worker control of society’s productive infrastructures and of the social product was seen by the autonomists as anemic. Instead they sought to confront the capitalist value-form as it is embedded in the finest pores and capillaries of lived existence. In practice this meant extending their analyses from theorizing the shop-floor in isolation, to understanding the role of capitalism in transforming humanity on the level of subjectivity in the streets, at home, in schools, and beyond. To that end, their analysis began from an expanded conception of the worker which included unwaged workers, students, and others who were often excluded from traditional conceptions of the “working class.” But the theorists involved would perpetually struggle to reconcile their social positions in relation to an expanded conception of the working class. As Wright carefully charts, the productive antagonism between workers and theorists is a thread that runs throughout the history of workerism.

In his new book, The Weight of the Printed Word: Text, Context, and Militancy in Operaismo Wright returns to the same historical period but with a different body of material and a new set of aims. Whereas Storming Heaven offered an historical overview of a theoretical tendency through the lens of individual thinkers, his new work analyzes the collective intellectual production of the workerist tendency as found in texts of shared or unknown authorship. Wright examines these deindividuated textual forms, the “expression and communication” of the Italian Autonomist tendency, with at least four explicit aims. First, to better understand “why and how specific documentary forms were created and used within the setting of particular struggles or campaigns.” Second, to see how these texts can illuminate the “practice of workerist militants.” Third, to provide a corrective to prior accounts of the historical period that overemphasize the contributions of individual theorists. And finally, to take a preliminary stab at outlining a “materialist and historical critique of document work within radical social movements.” However, Wright is quick to clarify that his concern is not simply with textual analysis; he wants to understand not only the author’s intended meanings and desired effects, but also the way these ideas were read, interpreted, and deployed. In a moment where mass media, social media, and electronic communications in general are driving profound shifts in thought and action across the world, it is invaluable to consider how political force is theorized, circulated, and embodied in and through media.

“What are Militants? Ceto politico and ceto operaio” The title of the book’s first chapter (excerpted below) poses a question. In answering it, Wright sets the stage for one of the book’s central themes, which concerns the tension between the “stratum” of political militants and that of the worker, and more specifically, how this tension can be traced in the anonymous and collectively written documents that have historically been neglected in other accounts of the period. Workerist theorists were centrally concerned with the production and reproduction of the revolutionary subject. For many comrades of the 70s, the central role of the intellectual was to identify the process of subjectivation within the working class, and the force of the written word in this process cannot be overstated. We don’t share these problems today, as the question of the revolutionary subject has been cast aside by popular struggles, or, all the same, it has become the unique obsession of movement-managers and reformists. In any case, we are inspired by Wright’s analysis of language and communication, of how increasingly unstable societies, then and now, can utilize novel communication technologies and strategies to catalyze unruly struggles and to subvert mainstream discourses, for better and for worse.

-Gabriel Piper November 2021

Our time is the time of militants. -Danilo Montoldi1 The truth of theory lies in commitment. -Raniero Panzieri2

Members of a self-defined anti-capitalist movement’s ceto politico or "political stratum" are recruited from a variety of social backgrounds, play a range of roles, and are designated in different ways.3 While the size and weight of this stratum have fluctuated with the vagaries of conflict within capitalist social relations, its generation and reproduction has nonetheless been intrinsic to those very social relations. In the period under consideration here, "militant" was the most common term used to denote an individual member of the Italian left’s ceto politico, although "activist" and "cadre" were also used: sometimes as synonyms, other times not.4 Amongst the accoutrements associated with their role, the membership card of an organization typically held considerable importance.5 Even in its absence, what bound together the components of this stratum from the subjective point of view was a vocation, a calling: "making of politics a life choice."6 As Negri put it,

It is difficult to convey what life as a militant meant not only for twenty-year-old workers and students but also for a man of thirty, thirty-five. Not only did it demand a total commitment in terms of time, a risky and exciting adventure, it also demanded an effort of self-transformation, in terms of rationality, affect, theory and politics. There was the work of agitation: understanding what had transpired, translating it into common language, disseminating judgement on the events, and all this in a continuum of news and testimonies and group reflection, receiving and bringing back knowledge and decisions.7

Montaldi once wrote of those militants he interviewed in the 1960s that they “often see politics as ‘something dirty’,” while adding that “for all [of them], politics is something that requires commitment as a group as well as an individual.”8 This shared undertaking was to be instantiated by “organizing the collective capacity to act” lying latent within the broader movement.9 The quest to identify such potentiality, searching for “the grand in the minute” that might gesture towards a shared project able to spring forth from within – yet also reach beyond – the here-and-now, meant that militants were typically “somewhat ‘outside’, outside the daily behavior of others, and often ‘set apart’ [un isolato].”10 In the words of Augusto Illuminati, “for the revolutionary, the present is charged with the future,” while for Gigi Roggero, revolutionaries “act within and against history; they do not follow the spirit of the times, but rather assault it.”11

What has frequently divided militants, both between and within their rival groupings, are disagreements as to how that task of “organizing the collective capacity to act” might best be realised. At the same time, according to Montaldi, seeing as these individuals “are a part of the class that is disposed towards organizing the whole,” it followed that even in the absence of shared organizational identities such militants “represent ‘the party’ within the class.”12 All told, the relation between class, movement and militants has always been a complex one: in the words of the Askatasuna Social Centre in Turin,

Militants form themselves in movements, and movements form and select militants. This is a spiral process that is not given once and for always, but one that must be continually cultivated, nourished and strengthened.13

As Gerd-Rainer Horn has made clear, this reciprocity between militants and movements was never so acute, nor the level of engagement so intense, as during the decade or so that followed the (global) events of 1968.14 This was true above all for Italy where, as Negri has indicated, a distinctive feature of the local radical ceto politico in this period lay in its ability to reproduce itself in a sustained and extended manner:

[T]he absolutely exceptional thing, above all in comparison to other European movements, is continuity, and this can be explained only if we address that period of formation. The continuity, this movement that produces a ’68 that lasts for ten years, can arise only because there is already a wealth of cadre, a social consistency in the movement that permits reproduction. There is a political subject that reproduces itself and has the capacity to do so, and capacity means a whole bundle of things. This isn’t a movement that arises on the basis of four intelligent people, it’s a movement that has the capacity to reproduce itself in terms of money, the production of propaganda materials, of formation and information, from leaflets to radio, therefore.15

To the extent that a movement generates its own institutions, the ceto politico provides the milieu from which their staff can be drawn. In movements that do not (or no longer) seek to overturn the dominant social relations, the ceto politico typically subordinates its organizing role to that of representing particular interests, whether within the formal political arena or on the industrial front or through the various special interest groups that frequently populate the public sphere. In this context, competition over access to resources predicated upon that representative function – what Weber once termed living ‘off’ politics as opposed to living ‘for’ politics – can be every bit as fierce as any ideological tussle.16 In movements that on the contrary aim to contest the constituted order, the ceto politico’s role is as indispensable as it is laden with ambiguity:

[I]n considering the movement, we can’t forget that it is also a specific social layer, a ceto politico (to use that horrible term) that posits itself as the relatively stable expression of social antagonism, as its memory, as the bearer of social values expressed by class behaviors. Although the movement, in this second sense, is something different from the class movement proper, one can’t understand the latter by overlooking the former. The political practices, the analytical and organizational instruments of the movement’s ceto politico play a notable role in the general evolution of struggles.

The movement’s ceto politico oscillates between its various roles, therefore, in a manner that is hard to unravel. It can pose itself simultaneously or alternatively as a minority agent for class self-organization, or as a simple appendage to traditional organizations and rules; as a movement of self-awareness, or as the bureaucratic and authoritarian direction of struggles.17

When, as would be the case in the era of ‘realized socialism’, a party’s rise to power proves to be at the expense of class autonomy, the collective body of militants will also be destroyed in the process: either literally, through the purges inherent to such regimes, or else by its mutation into something alien, as one component of a new dominant class. For as Franco Milanesi has argued forcefully,

practical work stops at the point where power begins...the militant can stay in a party and make it an instrument of force and transformation, but there is no longer a place for him or her in a party that has become a state.18

The reality that members of an anti-capitalist movement’s ceto politico may have quite disparate social origins has inspired a number of lively, even divisive debates over the last century or so.19 Throughout all the twists and turns of those polemics, a constant reference point has remained the strategic importance of individuals who have become militants not only due to some sense of vocation, but also as a result of their subjective experiences as proletarians. A key instance in the mid-1960s of this ceto operaio, as some Italian revolutionaries would later call this social layer within the working class, was the phenomenon that Alquati then termed ‘factory communists.’ These were cadres who continued to organize workplace struggles, even as many of them chose to abandon the Partito Comunista Italiano (pci).20 Indeed, the ceto operaio within Italy’s workplaces would be massively extended as a consequence of the heightened class conflict that marked the end of the decade – leading, as Alberto Magnaghi once noted, to

The construction in three years, from ’67 to ’69, of a workers’ ceto politico that went from a few old-timers in the factory commissions to around one hundred thousand worker cadres, able throughout Italy to re-govern a production cycle and to speak of political programs.21

Anticipating this “new muster of the Italian working class’ revolutionary militants” in the pages of Classe Operaia, Alquati had argued in 1965 that recent struggles had seen ‘an important modification in the figure of the working class militant’:

It is important to address this new figure of the militant, clarifying its ambiguities, its transitory characteristics, its dangers, but also the wholly positive function in the current situation of the new militants. These must be considered as part of the working class, seeing as: they are definable precisely on the basis of actions that unfold within workers’ struggles; they already express, at a potentially subjective level, the action of creation, connection and discovery of the mechanisms of the unification and selection of movements of workers’ struggle. Therefore the content of this new figure of the militant is not merely ‘organizational’: it entails a capacity that expresses itself in relation to workers’ struggle.. these militants are an unknown and uncontrollable force. If they remain isolated, they will ebb [rifluiscono], and it will be a long time before the tide turns again. If organized, they can provide the first step towards a new leap in the political struggle.22

Throughout the history of twentieth-century anti-capitalist movements, the relationship between those militants formed directly within clashes in the factory or community and the radical ceto politico as a whole has proved a difficult and even vexing one. Writing in the 1990s, Alquati insists that the term ‘militants’ not be confused with, for example, ‘the members of the sects and of the historic organizations as such’. Instead, they should be defined by what they ‘did and how they operated, rather than by their location’, and so be best understood as ‘the nerve center of so-called subjective class forces’.23 Addressing the question from a different angle, Negri has pointed out that Augusto Finzi and others amongst the first generation of autonomist industry militants had been guided in their political engagement by an assessment of their immediate circumstances within a given class composition, rather than in response to the direction of some external political organization:

Whereas in the parties or groups a cadre was a militant who maintained contact with the party structure and officiated the interpretation of the political line in the name of the center, in Autonomia a cadre was normally a worker who, along with their workmates [compagni], expressed the political line from below, from within the workplace.24

Things would become more complex as time went on, and new groupings sprang up within Autonomia that did indeed, in certain important ways, more resemble the traditional political sects of the far left.25 What happened in such circumstances when the goals and aspirations of the ceto operaio threatened to diverge from those of the ceto politico as a whole?26 In the specific case of Italy in the late 1970s, questions like this would lead Sergio Bologna to warn that the “workerist political class” within Autonomia Operaia had to bear responsibility for “reproducing leadership elites that are elites of revolutionary bourgeois, of having suffocated — like their illustrious predecessors — the working class direction of organization and the movement.”27 A few years later, Bologna would take this line of argument still further, noting the post-1968 “formation — through the struggles in the universities — of a ceto politico that identified with its own function of revolutionary vanguard and aspired, according to a model oft-repeated in history, to assume the command, the political direction of the class movements,” before wondering whether “the failure of that ceto politico must be considered a stroke of luck or a misfortune for the Italian working class, the loss of a precious social ally or the eclipse of a dangerous new boss.”28

[In t]he constitution and development of the workerist component of this ceto politico, and its encounter with the ceto operaio of the 1960s and 1970s — a process that was further entangled, like all radical currents at the time, with a wider mood of social unrest and revolt dominated by youth29 — ...documents would once again play an indispensable role. Briefly examining a piece of early 1980s satire may prove useful. A snapshot of the ‘Trontian amongst the thorns,’ published in the mainstream weekly L’Espresso as a sidebar to a feature article on Mario Tronti, provides one outline of the sundry ways in which a workerist political militant might seek to influence the world around him.30 Smitten with Tronti’s essays back in his teenage years, this individual had subsequently been inspired to collect, “not without some effort, the complete runs of Quaderni Rossi and Classe Operaia, which he studied with religious application.” Soon he could be heard irritating other members of his Communist youth cell through a series of “crazed interventions, all ‘wages’ and ‘mass worker,’ paralyzing them every so often with a ‘political class composition’ that he casts off as if it was nothing.” Somewhat diffident before the student movement of the late 1960s, he found himself re-energized by the Hot Autumn of 1969, during which “he cyclostyled all 300 pages of Operai e capitale and distributed them, at a militant price, outside the university entrance.”31 Atonement for a brief interlude in Potere Operaio was granted after “a letter of penitence and abjuration” secured his readmission to the PCI, where he continued to circulate Tronti’s pronouncements in cyclostyled form: everything from the pamphlet Autonomia del politico, up to and including “Mario’s conversations.” At last count, “he is studying the seventeenth century. If he is still cyclostyling, now it is ‘Mario’s’ lessons at the University of Siena. He awaits the latest essays with trepidation. His future is uncertain.”

The humor may be laid on rather thickly, but none of that obscures the absolutely central place of documents for this portrait of one workerist’s political engagement and identity. More generally, we can note that with three daily newspapers, more than a dozen publishing houses, and hundreds of periodicals both regular and irregular to draw upon, members of the ceto politico within Italy’s far left relied heavily upon the printed word in their efforts to communicate amongst themselves and with others.32 To quote a former leader of Avanguardia Operaia,

It was a period not only of radicalization leftwards, but also the formation of tens of thousands of political and movement cadres. It was probably one of the happiest times for the Italian left as a whole: that type of cadres, of militants, was the best that the Italian left had produced (even compared to other moments in history), in terms of quality, collective sense of participation, democratic ethos [democratismo] and civility in relations — all things that were then being extinguished within the PCI... There was a great quantity then of newspapers big and small, reviews, pamphlets, books: a great quantity of publishing firms small, medium and big – including some really important ones: think of Feltrinelli, which produced loads of materials. There was just an embarrassment of choices. Bear in mind that the organizations of the New Left were strongly militant, comrades were active in terms of political action, party meetings, propaganda initiatives; they participated in political-theoretical education; they bought the party publication; if they read it, they discussed it, and naturally they also bought other things: books, newspapers. They didn’t just read things from their own party, so we can say that their knowledge was rather broad. They read everything, within reason.33

It is on the nature of these things that were created and read by the ceto politico that [the present book is focused.]

Excerpted with permission from Steve Wright, The Weight of the Printed Word - Text, Context, and Militancy in Operaismo, out now in Brill’s "Historical Materialism" series.

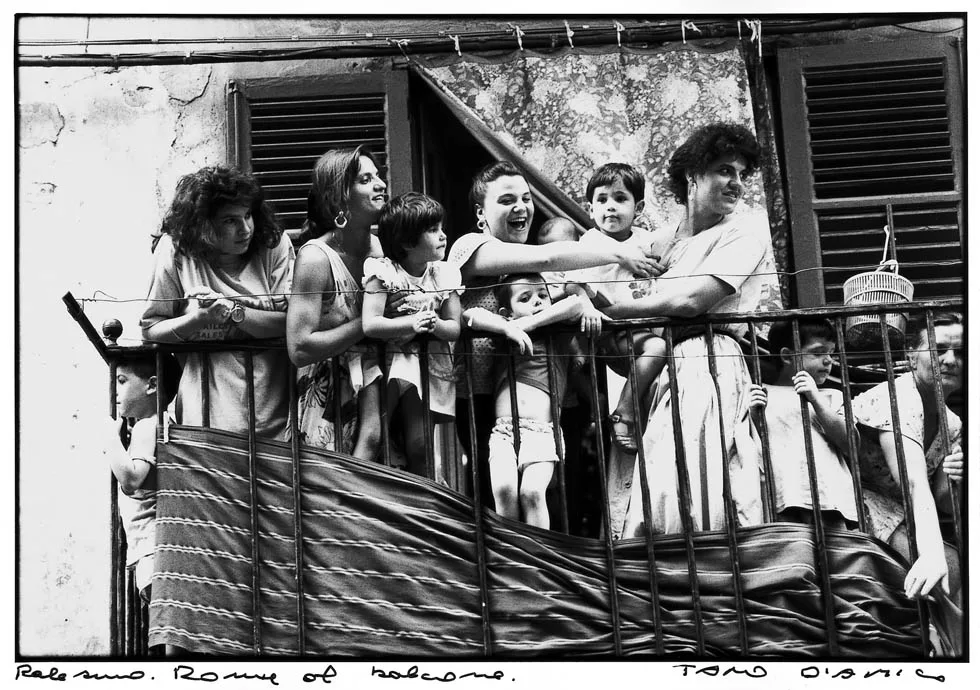

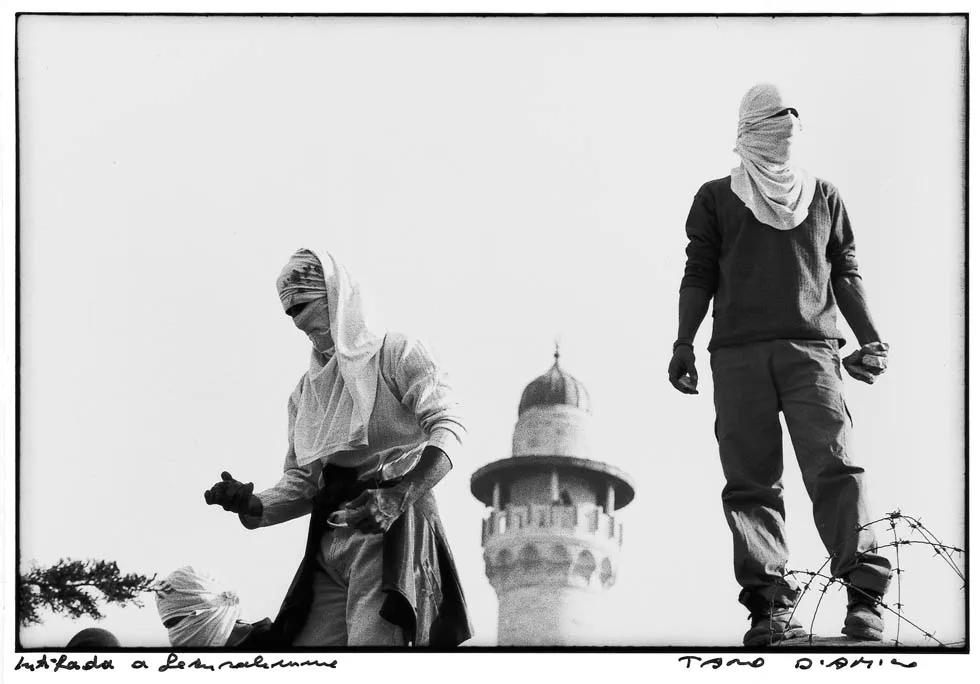

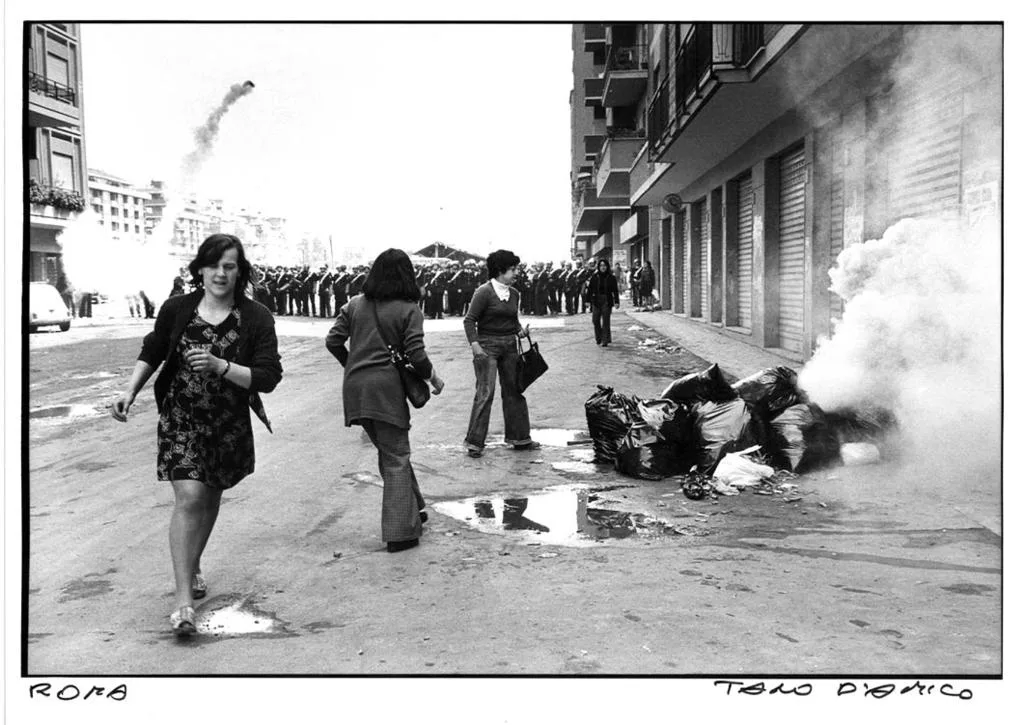

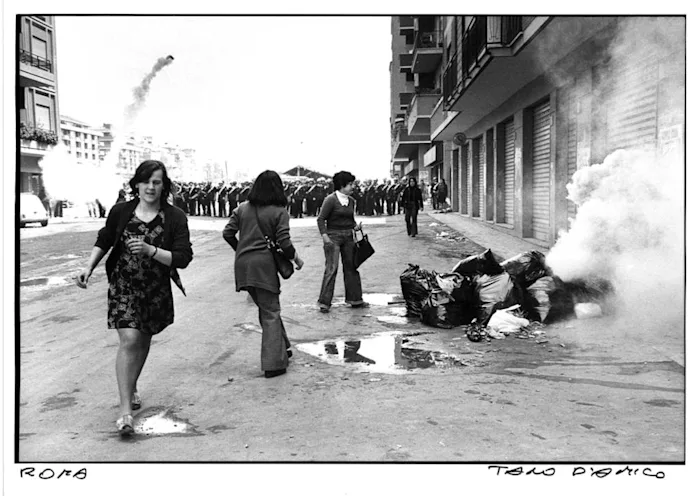

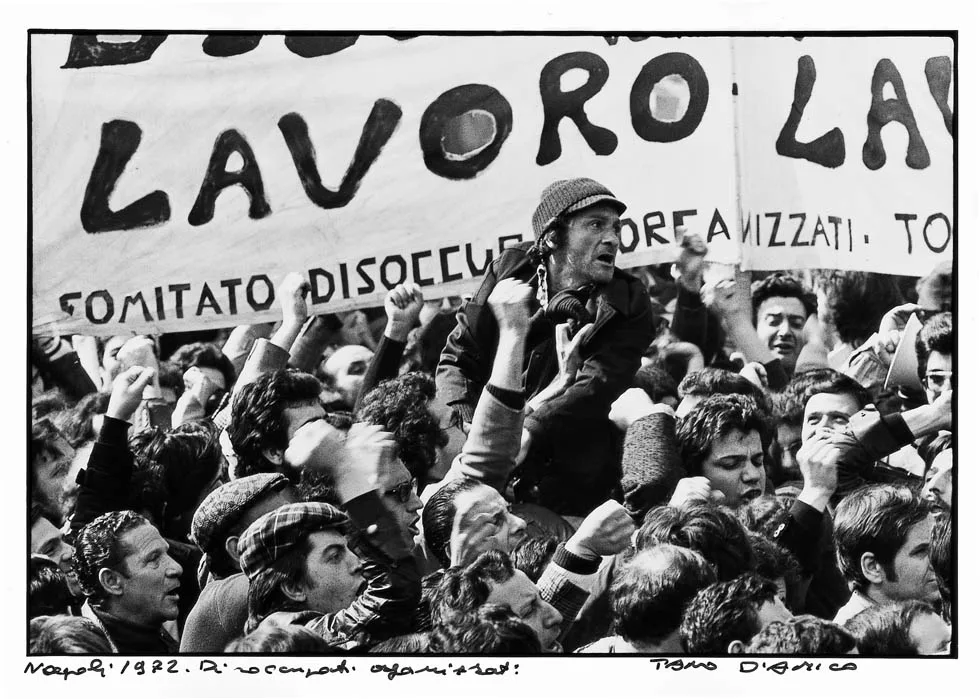

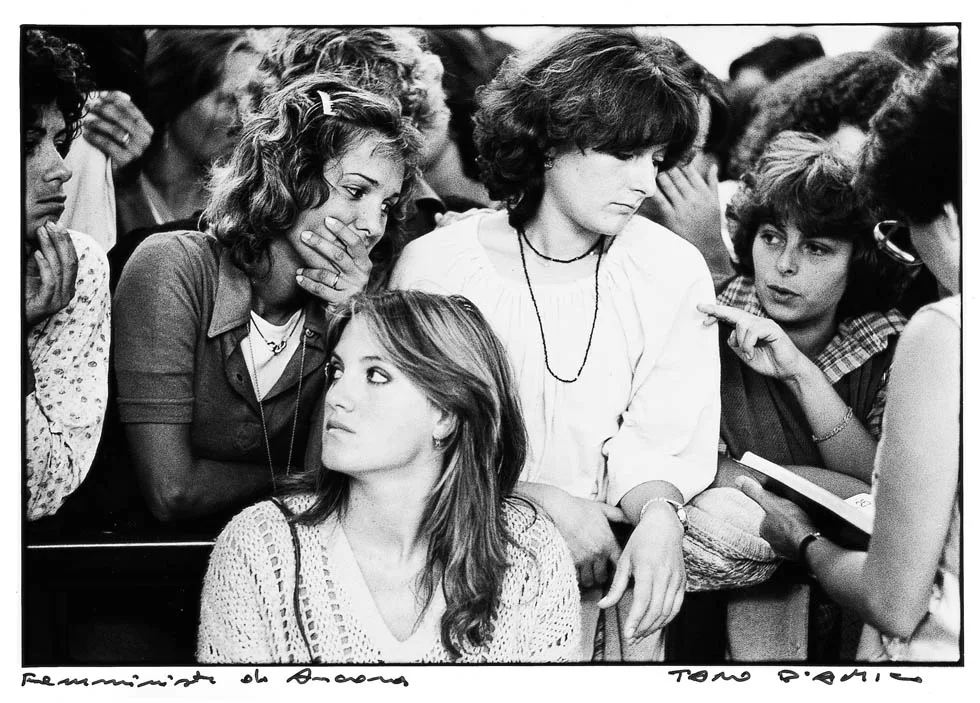

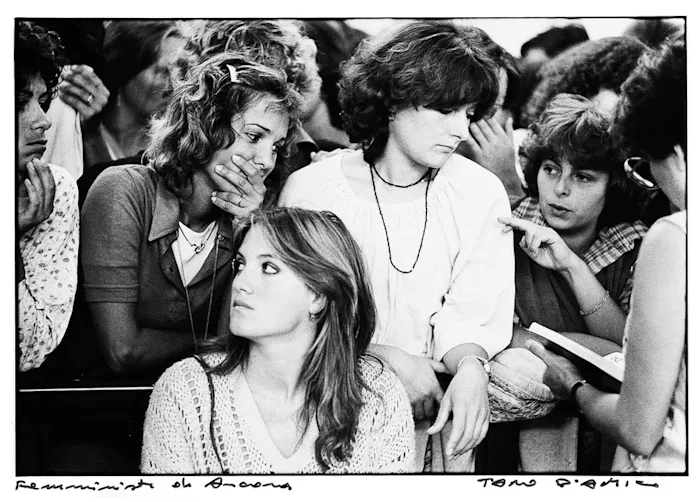

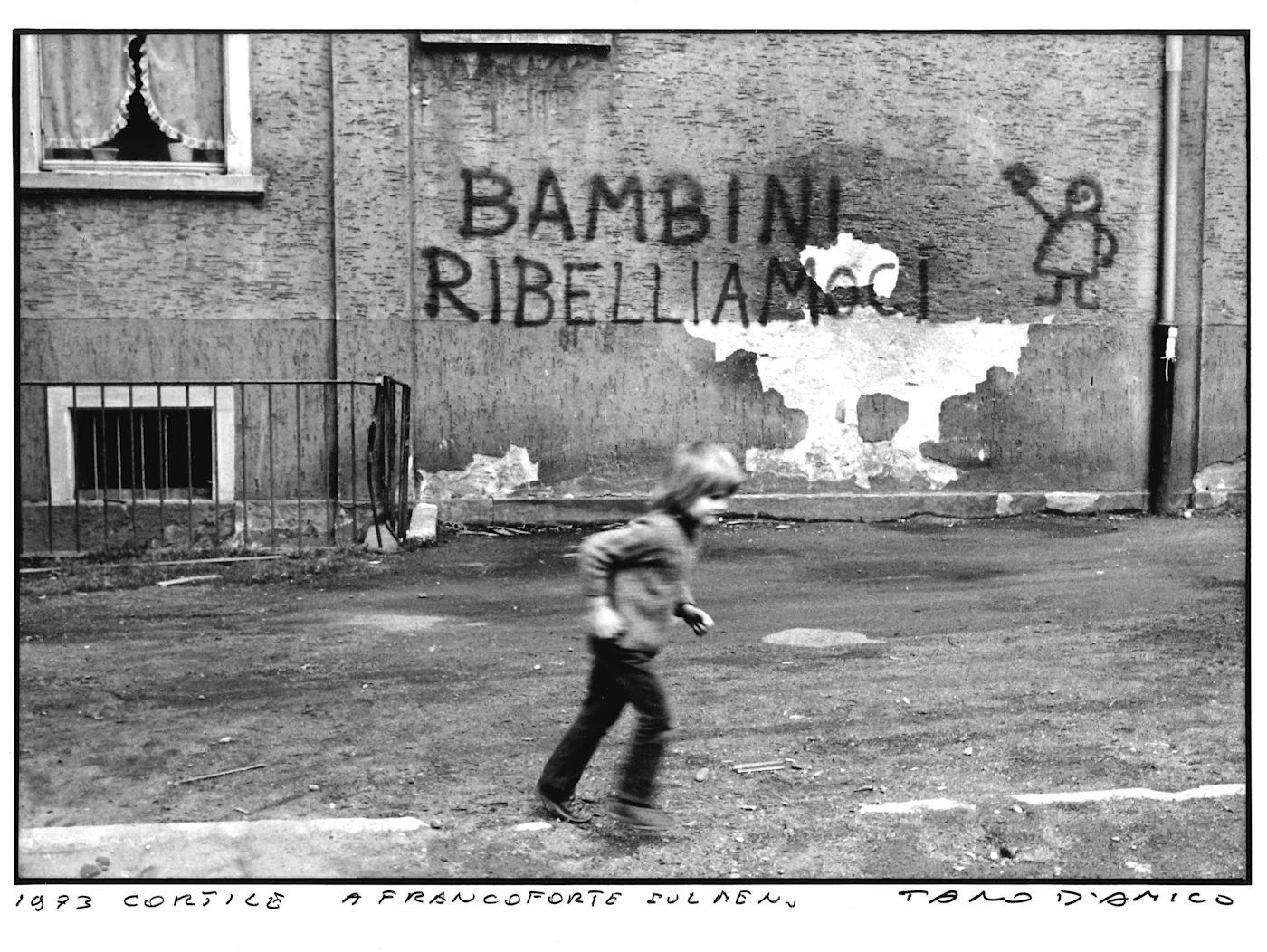

Images: Tano D'Amico

Notes

1. Danilo Montaldi, Militanti politici di base [Autobiographies of political militants], Einaudi, 1971, 393. ↰

2. Panzieri to Asor Rosa, 10 May 1962. ↰

3. As I have argued elsewhere, "Like all political ensembles, whatever their creed, Autonomia possessed its own ceto politico: a multi-layered stratum of activists committed to the movement’s continuity through the ups and downs of its daily routine. Such layers were constituted around different, yet often interpenetrating axes: class location, ideology, shared experience, personal and group loyalty. As the movement waxed and waned across the decade, so too would the various fortunes of different layers and aggregations within this stratum." Steve Wright, "A Party of Autonomy?," in Resistance in Practice: The Philosophy of Antonio Negri, Vol. 1, Pluto, 75. ↰

4. Activist/militant/cadre: Montaldi (1971) tends to use the first two interchangeably; for Augusto Illuminati, militancy came to be supplanted by "activism" with the rise of what others have called ‘new social movements’, above all in the period of "post-Fordism." The word "activist" appears more than thirty times in the essays from the 1960s that make up Alquati’s book Sulla fiat, the word "militant" more than forty times, and the word "cadre" more than 100 times (although perhaps because much of Alquati’s attention in the second half of his book is precisely upon current and former pci cadres as a specific layer amongst militants). Whatever nomenclature is most correct, what has remained constant is the function of the ceto politico within a movement’s nervous system. For their part, the authors of Futuro Anteriore seek to distinguish cadres (understood as a particular layer whose specific function it is to bring to bear a political "line" developed elsewhere) from those militants who are able to be "more autonomous" and creative in their political work. Finally, in a recent interview, Giorgio Ferrari has wanted to emphasise that in the 1970s, the word "militant" had not yet become "a synonym for hardness, rigidity or even violence." See Augusto Illuminati, Del comune. Cronache del general intellect, Manifesto libri, 2003, 19; Franco Milanesi, Militanti. Un’antropologia politica del novecento, Edizioni Punto Rosso, 2010; for Bologna’s comments, see Patrick Cuninghame, Autonomia: A Movement of Refusal: Social Movements and Social Conflict in Italy in the 1970s, PhD thesis, Middlesex University, 2002. Available here; Giorgio Ferrari and Gangi, ‘La parola alla radio’, Zapruder 34, May–August, 2014, 130. ↰

5. "The twentieth century political militant is configured according to groups, with all the problematics (relationship between party and masses, between leaders and members, between organizational systems and subjective liberties) that mark such a history." Milanesi (2010), 24. ↰

6. Milanesi 2010, 27. See also Illuminati, 2003. The author discusses the question of "calling" in terms of both Weber and (via Agamben) of St. Paul. ↰

7. Antonio Negri, Storia di un comunista, Ponte alle Grazie, 273. ↰

8. Montaldi (1971), xvi. ↰

9. Rodrigo Nunes, ‘It Takes Organizers to Make a Revolution’, Viewpoint Magazine, November 2017. Milanesi identifies "the 'essential' characteristics of militancy’ as a) the centrality of choice as a subjective option capable of having a bearing on events; b) politics as constant, total commitment, involving one’s whole life and all its expressions on both the public and private fronts [fino a comprendere in essa dimensione pubblica e privata]; c) the central function of 'ideology' as the motivational theoretical cornerstone of activity; d) the 'lavish' [dispendioso] nature of this politics; e) the centrality of certain theoretical-political nodes, albeit bearing a range of connotations: equality, justice, sociality; f) actions undertaken according to a horizontal conception of politics – that is, as potentiality [potenza] rather than as power [potere]; g) a marked contrast/distinction [contrasto sostanziale] between militant subjectivity and institutions; h) an alternative anthropology and value system to those of the bourgeoisie; i) a projection of praxis as the preliminary definition of a historical and anthropological perspective." The discussion in D’Arcy’s Languages of the Unheard: Why Militant Protest is Good for Democracy (2014) is also informative, although it focuses less upon militants as a layer within a movement, and more upon militancy as a distinctive tone of struggle. ↰

10. Montaldi (1971), xviii. On Montaldi’s notion that "political rank-and-file militants" often find themselves somewhat "at variance with their own historical time," see the discussion in Gallerano 2007, p. 64. Writing about British mining communities of a century ago, Stuart Macintyre similarly notes the existence of an "earnest minority, made up of a variety of trade union and labor activists and a sprinkling of Marxists [who] were at once representatives of and strangers in their own society" – Stuart Macintyre, A Proletarian Science: Marxism in Britain 1917–1933, Cambridge, 1980, 39. ↰

11. Illuminati (2003), 17; Gigi Roggero, Elogio della militanza. Note su soggettività e composizione di classe, Derive Approdi, 2016, 211. At the same time, the former tells us, this is – again not unlike St. Paul – a "refusal to reconcile oneself" with the times in which one lives. ↰

12. Montaldi (1971) xii. While Montaldi speaks of "political rank-and-file militants" here, I believe he is referring specifically to the ceto operaio – about which, more below. Montaldi adds "they are not a social stratum," a point which may well be true, but only so long as they do not consolidate into a ceto politico in their own right. ↰

13. Centro sociale Askatasuna, A sarà düra. Storie di vita e di militanza no tav, Derive Approdi, 2012, 35. ↰

14. "New left activism [of the previous decade], though generally decidedly more pronounced than equivalent engagement in the old left, rarely approached the near-full-time commitment demanded of most far left members." Gerd-Rainer, The Spirit of ’68: Rebellion in Western Europe and North America, 1956–1976, Oxford UP, 2007, 162. ↰

15. Antonio Negri, "Intervista a Toni Negri – 13 luglio 2000," now in the CD-Rom accompanying Guido Borio, Francesca Pozzi, and Gigi Roggero, Futuro anteriore. Dai “Quaderni Rossi” ai movimenti globali: ricchezze e limiti dell’operaismo italiano, Derive Approdi, 2000, 10. ↰

16. For a relevant discussion in terms of the US union movement, see Immanuel Ness, Trade Unions and the Betrayal of the Unemployed: Labor Conflicts During the 1990s, Routledge, 1998, Chapter 1. ↰

17. Guido Giovannetti, "Il movimento e le leggi della guerra," Collegamenti 8, June: 5–9, 1980, 7. While holding – in a statement that echoes both Montaldi and Alquati, that "[m]ilitants are the link that structures the movement, that gives it form, potentiality and organisation," the Askatasuna social centre has argued that they can nonetheless refuse to constitute themselves as a ceto politico, and thus avoid the latter’s immanent potentiality to subordinate struggles to its own ends – See Centro sociale Askatasuna (2012), 23. Roggero identifies another danger of the current period, wherein "[t]he measure of discourse ceases to be the materiality of processes of struggle, of organisation and relations of force, and becomes instead the militant community itself." See Roggero (2016) 12, 206. ↰

18. Milanesi (2010), 81–2. For a discussion of the process through which a new dominant class emerged after 1917 from the ceto politico of the Russian revolutionary movement, see David Camfield, "From Revolution to Modernising Counter-Revolution in Russia, 1917–1928," Historical Materialism 28(2): 107–39, 2020. ↰

19. Marshall Shatz has explored the views of Jan Waclaw Machajski, who denounced the early twentieth-century radical intelligentsia for its aspirations to dominate the labour movement of Imperial Russia. See his Jan Waclaw Machajski: A Radical Critic of the Russian Intelligentsia and Socialism, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1989.↰

20. Romano Alquati, Sulla fiat e altri scritti, Feltrinelli, 1975, 19, 290, and 227, where he noted ‘a growing outpouring [travaso] of cadres from the party to the union, a phenomenon that became accentuated in 1964’. ↰

21. In Aldo Grandi, Insurezzione armata, Rizzoli, 2005, 204–5. While Magnaghi uses "ceto politico," I would argue that he is using the term to refer to a phenomenon more analogous to what is here designated as the "ceto operaio." ↰

22. Alquati (1975), 226, 227, emphasis in the original. ↰

23. Romano Alquatio, "Su Montaldi, (Panzieri, io) e la conricerca," in Camminando per realizzare un sogno commune, Turin: Velleità Alternative, 1994, 192. ↰

24. Negri (2015), 461. As will be seen, the independence of the likes of Finzi would be one of the defining attributes of the circle active in Porto Marghera. Interrogated by a judge concerning the post-1968 revolutionary groups in general, and Potere Operaio in particular, Negri would assert that "the function of the leader and of the boss [capo] was negated by the theory and ethical sensibilities of the militants of these organisations." See Collettivo editoriale, Il processo all’autonomia operaia, 10/16, 1979, 58. Such a statement seems to superimpose the culture of the later 1970s – by which point, within and around Autonomia, "words like secretary, leader, branch secretary, had no place – the only term used was 'militant' or 'comrade’ upon the earlier part of the decade, a period characterized on the contrary by Bologna as "the Golden Age of ultra-Leninism." See Roberto Faure, "Achtung autonomi," in Gli anni del 68. Voci e carte dall’Archivio dei Movimenti, ed. Galletta et al., Il Cannetto Editore, 250. And Sergio Bologna, "Rapporto società-fabbrica come categoria storica," Primo Maggio 1, 1974 (Available in English on Libcom). ↰

25. Wright (2005). ↰

26. In moments where the ceto politico’s capacity to act is severely hampered — for example, by state repression — the distance between these two layers may become extreme. For an informative study of the disconnect between ‘workers’ opposition’ in the factory and formal leftist political resistance to fascism, and how this played itself out as the Nazi regime consolidated its power, see Tim Mason, "The Workers’ Opposition in Germany," History Workshop Journal 9, 1979. Similar disjunctures are explored in the Soviet Union of the 1920s by Pirani 2008. For his part, Tronti would argue in the 1971 postscript to Operai e capitale that such a disconnect should not always be considered an impediment to class autonomy: "the American class-struggles are more serious than European ones in that they obtain more results with less ideology...The smaller the contribution of leftist culture, the more the class pregnancy of a given social reality comes forward." See Mario Tronti, "Postscript of Problems," 1971. Available here. ↰

27. Sergio Bologna, "Amo il rosso e il nero, odio il rosa e il viola," in La tribù delle talpe, edited by Sergio Bologna, Feltrinelli, 1978, 155. ↰

28. Sergio Bologna, 1981a, "Per una 'società degli storici militanti’," in Sergio Bologna et al., Dieci interventi sulla storia sociale, Rosenberg & Sellier, 1981, 15. ↰

29. There are many studies that address the convergence between youth culture and postwar radicalism. Two of the best are Horn (2007) and Diego Giachetti, Un sessantotto e tre conflitti. Generazione, genere, classe, Pisa: BFS, 2008. ↰

30. Stefania Rossini, "Le front populaire," L’Espresso 17, February 1980, 71. On a more serious and perhaps controversial note, Cazzaniga argues that Quaderni rossi and Classe Operaia were also fundamental for "the composition of the left’s ceto politico e sindacale over the last twenty years, with particular reference today to the Pds and Rifondazione Comunista." See Gian Mario Cazzaniga, 1995, "Intervento," in S. D’Albergo et al., Ripensando Panzieri trent’anni dopo, Pisa: BFS, 1995, 162. For an excellent account that places Tronti’s writings of the 1960s in context, see the preface and introductory chapter in Andrew Anastasi, The Weapon of Organization: Mario Tronti’s Political Revolution in Marxism, Common Notions, 2020. ↰

31. "Militant price" was often a euphemism for donation. ↰

32. Diego Giachetti, "L’area della rivoluzione nell’Italia degli anni Settanta," 2013. Available here.↰

33. Luigi Vinci, in Roberto Niccolai (ed.) Quando la Cina era vicina. La rivoluzione culturale e la sinistra extraparlamentare italiana negli anni ’60 e ’70, BFS, 1998, 63. Interesting insights into the range of audiences within the Italian left and labour movement that read the workerist review Primo Maggio during the 1970s can be found in Cesare Bermani and Bruno Cartosio, “'Piccola storia' di una rivista," in La rivista "Primo Maggio" (1973–1989), edited by Cesare Bermani, Derive Approdi, 2010, 47–50. ↰