Breaking the Waves

Nicolò Molinari

What form should revolutionary organization take today, now that its longstanding models are in crisis? What conversations do we need to be having at an international level, in order to develop a shared strategic orientation toward insurrection? Surveying recent movements in France and in Atlanta, Nicolò Molinari traces the contours of our current cycle of struggle.

Other languages: Deutsch, Français, Español, Italiano

In a recent text, Temps critiques1 reflects on how the intergenerational composition that was lacking in the Gilets jaunes movement began to make its appearance in the gestating movement against pension reform in France. The authors describe what they call an alliage2 of circumstance produced by the temporary fusion of different social fragments, a category that recalls what Endnotes has referred to as the "problem of composition" in recent movements.3 Young people of all kinds have given a new impetus to the struggle, resulting in a powerful surge of the cortège de tête in the dynamics of confrontation with the police, and causing the unions to lose control over the squares. At the same time, the youth have redefined the role of school and university occupations, transforming them into organizational bases for actions that then spread across the cities. In this way, occupations take on a different meaning than during past movements: instead of being understood as a reclamation or reappropriation of educational institutions, students are reworking the classical practice in their repertoire into a new form capable of composing with the movement against pension reform. It is in this sense that we must speak of an alliage taking place, which faces off against the concentrated powers of Macron’s State as well as the decentralized power of the economy.

The conflictual shape of the March mobilization in France, which tended to favor direct actions and blockades, is linked both to this compositional configuration of the various subjectivities involved within it, and to Macron’s moves. The rhythm of the movement developed in response to Macron’s “coup,” which, by circumventing all the usual institutional oppositions such as unions and parties, meant that the only opposition that remained possible was a direct and unmediated one. It is here that the youth and all those more "radical" components of the movement have found space to shake up the mobilization by assigning greater centrality to a repertoire of practices made up of roadblocks, pickets, black blocs, wild demonstrations, etc.

A text appearing in Lundi matin4 on April 11th identified three moments of mobilization: the first (when the reforms were still being debated by the government) centered around the construction of a united mobilization by the unions, the second around the combination of strikes, blockades, and pickets in key sectors of the economy, and finally, following the forced passage of the pension reform, we saw the autonomous and widespread proliferation of nighttime rioting and the blockading of circulatory flows. According to the authors, it was only during this third phase that the possibility emerged for the mobilization to leap out of the reactive pattern it had adopted with respect to the government’s moves, to leap over the shoals of republican democracy and mediated forms of organization like unions or parties, and began experimenting with novel configurations.

In the face of the historic inefficacy of the union strikes (even when these became "general"), the practice of the blockade has taken on greater centrality. These blockades — which ranged from arterial roads to strategically targeted locations such as bus depots, refineries, and waste sorting centers — tended to decentralize the conflict, interrupting the military dynamic of direct confrontation with police. This was especially true when they cropped up unexpectedly in various parts of the city, paralyzing commerce. This form opened up a different rhythm for a movement that had been fully controlled by the inter-union assembly at the outset.

Space and place

As these texts indicate, the organization of combative blocs and actions has been most advanced where the mobilization has developed forms of coordination that operate outside the syndicalist framework, while remaining in direct relationship with the most determined bases within the unions. What became known as “Operation Ghost Town” [Ville morte], a series of paralyzing blockades that occurred in Rennes, Nantes, and Lyon, attests to the emergence of an autonomous trajectory within the mobilization capable of composing a revolutionary subjectivity that crystallizes into an antagonism to the state, while skirting the mediations of the union. The challenge of this new subjectivity lies in the need to continually reinvent its capacity for mobilization, coordination, and intervention within its blocs without allowing its tactics and strategy to harden and calcify, which makes it more predictable for the police, causing a loss of strategic advantage for the movement.

Meeting this challenge requires that struggles develop a territorial basis — be it at a neighborhood level, throughout a town or city, or even across a region — allowing them both to disrupt circulatory flows, while preventing the police from regaining control over its infrastructure and the flows that pass through it. For the level of coordination to reach a certain level of efficacy, a territorial dimension will always become essential. In the movement against pension reforms, for example, although the formation of conflictual spaces has been limited to student occupations and blockades, even beyond their purely operational function, these can also become meeting places capable of gathering together a range of different subjectivities, contributing to the construction of an an ethical and practical “we.” To date, the most advanced example of this simultaneous combination of conflictual forms capable of disrupting the circulatory infrastructure, and the placemaking impulse that creates an outside, was the roundabout occupations during the first three months of the Gilet jaunes uprising.

The creation of places belongs to the basic grammar of all recent movements, from the Movement of the Squares in Europe to the 2020 George Floyd uprising in the USA. In the wake of the American Occupy movement some comrades invoked the category of the “insurrectionary commune” in an effort to theorize how these places opened up by struggle experimented with forms of social reproduction outside the circuits of capital.5 Similarly, in 2020, autonomous zones were hatched from Seattle to Atlanta, attempting to give life to territories free of police presence.6 Although neither were without numerous difficulties, these experiences clearly show that the control and function of policing is not exclusive to the police, since the counterinsurgent role is often assumed by components of the movement.

Whether one considers these recent movements from a Marxist perspective (e.g. communization theory) or an ethical one, the creation of places in secession from, and in opposition to, governmental or capitalist control of territory constitutes the element through which different subjectivities build the common ground of their existence, and the possibility of duration. The decline of programmatic politics, as well as those built around social representations seeking integration into the spaces of the classical political sphere, leaves a void that is gradually being filled by the construction of new non-sovereign territorialities. The decline of demands-based politics paves the way for a new political geography in which what is at stake is the creation of new forms-of-life, places that are ethical before being physical, a fabric of mobile and unobjectifiable relations.

The point is not that physical places have become the primary stake in contemporary movements, but merely that their material and strategic infrastructure depends upon them. If we understand the term “autonomous zone” to refer to an area that is no longer dependent upon the region around it, well, such a thing doesn’t really exist. Neither is it merely a question of implementing a formal administrative model, as if “self-management” or the practice of gift-giving needed to automatically characterize the anti-capitalist orientation. Still less is it a matter of sovereignty and independence, of substituting State sovereignty with some other State-like sovereignty, particularly given the other equally terrible forms that can often be generated in these kind of attempts.7 In truth, “autonomy” as a strategic and revolutionary question is not primarily about self-administration or self-sovereignty, but is a tension or problem that emerges only within the dynamic space of an ongoing conflict: a struggle remains “autonomous” so long as it retains its capacity to continuously regenerate offensive and antagonistic forms.8 From this point of view, spaces in which we can develop alternative forms of organization and social reproduction are obviously helpful, but their emergence should not be understood as the end-point or culmination of struggle.

Territorial struggles

The George Floyd uprising in 2020, or the Gilets jaunes in 2018-2019 were moments of massive mobilization, insurrections that mark moments of rupture. They were not the result of a transcrescence of social struggles, nor did they represent the fulfillment of some program. Still, on a subjective level, they produced the kind of biographical rupture that often can make a return to an everyday life devoid of such intense moments of struggle even more unbearable. For those moved by a revolutionary ethical tension, it can be difficult to accept that one must wait for the next unforeseen uprising, in order to hurl oneself into it. In response, organizational questions tend to arise: how can we learn from these insurgencies, and at the same time move through moments of reflux?9

Hugh Farrell identifies in territorial struggles a form that conflict can take during phases of great reflux and general reaction, and which have certain characteristics in common with contemporary mass uprisings.10 Looking telescopically at the past decade, we see how, in different parts of the Western world, territorial struggles managed to agglutinate disparate subjectivities around an instance of defending a territory, along with a renewed impetus to inhabit and constitute it anew. This is true of the No-TAV struggle in the Susa Valley, the ZAD at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, in the NoDAPL struggle in North Dakota, as well as more recent conflicts, such as those against the mega-reservoirs like the one in Sainte-Soline, or the movement to Stop Cop City in Atlanta.

Since it is the territory that constitutes the vectors around which the struggle is articulated, the compositional processes they initiate also reflect this fact. This is why the “territorial element” in question is both physical — involving specific places that one would like to defend, or mega-projects one wishes to block — as well as affective, entailing a process of continuous redefinition and transformation generated by those who inhabit it.11 For example, the movement known as Les Soulèvements de la Terre (“Earth Uprisings”) has sought to weave a composition between different subjectivities that is, in some respects, similar to the movement against pension reform described above. In this case, the compositional fabric includes farmers, rural inhabitants, "ZADists," and the "climate generation," all of whom have been brought together by a series of territorial struggles scattered across France — the most infamous episode of which occurred against the mega-reservoir in Sainte-Soline.

A territorial element has also been on display in the struggle in Atlanta, which has gathered around the slogan "Stop Cop City / Defend the Forest." Since the contested site is not located in a rural area but is a forest within Atlanta (itself a city within a forest), the composition in this case has mainly articulated itself between various local youth subcultures, which are extremely vibrant (Weeks of Action are often punctuated by music festivals), who are joined by anarchist, and environmentalist elements from across the country, as well as local political groups such as community organizers, abolitionist associations (which try to give political continuity to the riots of the 2010s and 2020s), and religious communities.

The grammar of struggle in Atlanta and Sainte-Soline is unlike most leftist climate movements, which tend to favor mainly peaceful marches and symbolic actions aimed at cultivating "awareness" about the climate crisis. A strategic horizon that prioritizes making demands of the various institutions, while renouncing the possibility of originating alternative forms-of-life, amounts to a dangerous appeal to the sovereign horror of a “climate leviathan,” the same sort promoted by the green pseudo-Leninist Andreas Malm.

It’s worth noting that, whereas in "non-movements" such as the Gilets jaunes or the 2023 pension reform struggles the compositional process emerged independently of any explicit intention on the part of its individual segments, in Atlanta or Sainte Soline a strategy of composition has been explicitly and intentionally adopted (albeit only by a portion of the components) and advanced by certain pre-existing political networks. Such a strategy aims, through the cooperation of diverse groups, to articulate shared goals and to assemble or “compose” actions that escalate and intensify the antagonism. Although this process might at times take on the appearance of an alliage or fusion of diverse groups, it ultimately seeks to preserve their differences throughout the process of struggle itself, albeit without succumbing to the sclerotic tendency to prioritize reflections on identity over the victory of the struggle itself.

Unlike mass uprisings, territorial struggles are not simply ethical urgencies of refusal, but instead embody the threshold between the ethical and the political. In this, they raise pertinent organizational and strategic questions for anyone who questions how a struggle can become revolutionary.12 How are we to avoid the pitfalls of a Leninist avant-gardism, without succumbing to the opposite danger of the Bordigist spectator who merely interprets movements externally from the sidelines? How can we arrive at a logic wherein participants not only recognize themselves as integral parts of a spontaneous process in which an emergent strategy is developing, but feel authorized to introduce gestures that modify its basic platforms and processes, without attempting to control these gestures or their trajectories, and allowing them to be reproduced by others?

As a recent text13 on the cortège de tête reminds us, even numerically small subjectivities occasionally succeed in introducing tactics that have the power to modify and even destabilize the entire strategic plan of a struggle. Sometimes, destabilization is just what is needed to prevent a movement from crystallizing or stalling in the face of an impasse, and contributes to strengthening its conflictual bearing, broadening its tactical horizons, and nourishing its creative capacities.

In some ways, this is the wager of Adrian Wohlleben's essay, “Memes without End”14: by introducing gestures that spread and multiply beyond the subjectivities that initiate them, small groups can intervene in specific social movements and displace them out of their internally fixed conditions, thereby expanding their horizon for radical transformation. In order to push struggles or militant groups beyond their reformist or martyrological impasses, it is decisive to prevent the sedimentation of tactics, to subvert any exclusive control over practices, and work against the centralization of strategy.

Impasse

The impasse confronted by many recent struggles, particularly those of Earth Uprisings, seems to be very similar to that confronted by the pension reform mobilization: the crystallization of an antagonism that lodges the struggle in a substantial dialectic with the state. The stabilization of such a dialectic risks two sorts of impasse situations: first, a recuperation, depotentiation, or deescalation of the conflict, including the possibility of winning some concessions or a partial victory, as in the case of the ZAD15; second, a symmetrical conflict, which may then result, in the immediate term, in a highly militarized direct confrontation.

Turning our gaze toward ourselves, toward our subjectivity, we face the risk of solidifying our participation in the movement into a form of alienated militancy that produces a separation between us and what Bordiga would call “the historical party,”16 or what we can also call the real movement. This separation (the Bolshevik one), which sees a vanguard at the head of a movement and organizing it, and which served as an important tactical and strategic formula throughout the twentieth century, finds its echo in all those movement strategies today that aim at constructing counterpowers and counter-subjects, without realizing that the power it seeks to oppose has no specific consistency, and is in important respects "anarchic."17

Moreover, these analyses overlook the entirely decisive fact that the uprisings of our time exhibit a total absence of any mass political Subject capable of centralizing the conflict, which has been replaced by a fragmentation of mass subjectivities, and resulting in conflicts that are riven by a series of ethical tensions that can find no ideological, discursive, or programmatic common ground. From Hong Kong to Chile and the Gilets jaunes, the revolutionary "we" has collapsed into an experiential and ethical “us” that possesses no common language. Yet, precisely for this reason, it makes itself unavailable to the traditional modes of recuperation proper to classical politics. Anyone who seeks to imagine how the conflicts in our epoch could become genuine revolutions must wrestle with these realities, while abandoning nostalgia for (often mystified) past eras in which a mass subject formed the engine of struggles. We live in an epoch in which class finds no sociological or political unity, but only an ethical and subjective one, forged in and through the moment of the uprising. Class is traversed by a series of vectors that make it socially fragmented, of which "identity politics" constitutes only a symptomatic form.

Rather than artificially re-enacting new social or political unities, any revolutionary struggle must come to terms with this social fragmentation and the anarchic nature of contemporary power. Unlike the fantasy of a “constituent” or “counter-power,” the destituent option is the only one capable of proposing a revolutionary strategy amidst a reality in which the illusions of formal political representation are collapsing into simulacra. Under such conditions, an antagonism that is content to mirror the simulacra of its enemies can only run amok.18

Capital, having autonomized itself and entered its phase of real domination, no longer articulates itself according to a set of abstract or hegemonic principles. It possesses no other regulative principle aside from its own survival and reproduction, which will take place through violent repression if necessary. For this reason, it has no qualms about revealing its terrible brutality, by crushing whatever threat it manages to recognize. The dialectical relationship between capital and labor, dear to so many Marxists, is continuously broken by capital itself. Whether out of a nostalgia for some lost democratic horizon or otherwise, to think of reconstituting it by means of struggle is a losing wager, as the impasses in which the alter-globalization movement and the entire post-workerist proposal of Negri and Hardt have shown. How could we not see, in the police repression of Seattle 1999 or Genoa 2001, the specter of an easily fought and won civil war? While “Tute Bianche” [White Overalls] were battling simulacra on a purely symbolic level, the other side crushed the movement in violence and fear.

Similarly, one could read the murderous violence expressed by the police against protesters in Sainte-Soline on March 25 in this way. Whenever an antagonist force publicly raises the bar of the conflict and directs it to a highly symbolic level, it makes itself clear and legible to the repression, which has no particular difficulty in organizing itself and mobilizing any necessary means capable of crushing its forces. The question of violence must then disentangle itself from a double specular naiveté: on the one hand, from a non-violent victimhood that believes it can alter force relations solely through intervening at the discursive or cultural level through the denunciation of state violence; on the other hand, a reappropriation of violence that attempts to mount a symmetrical campaign of force against the State, which risks channeling the generative and inventive potentialities of the conflict into a confrontation between two established fronts, where one is entirely militarily dominant.

Destitution

Unlike symmetrical and dialectical models of confrontation, which oppose forms of government only in order to propose alternative ones, destitution is a form of conspiracy that aims to deactivate and disable the apparatuses that govern the life and conduct of the neoliberal subject, both territorially as well as subjectively. Therefore, a revolutionary (destituent) subjectivity in the current era empties power, while denying itself an identity or other forms of subjectification.

Destitution represents the opaque art of overturning the anarchy of power, in the direction of real anarchy, understood as a life that does not need legitimacy, rooted in the free play and exchange between forms-of-life. One way to do this, according to the Invisible Committee, is to expose the anarchy of power through actions that exhibit its groundlessness: this does not mean denouncing its violence in order to ellicit a democratic scandal, but rather striking at it in ways that show its true nature as devoid of any abstract legitimacy (a social contract, democracy, equality, nation, order, etc...). In the same way, a destituent gesture does not require legitimacy, since it anchors its expression instead within a sensible and evident truth and reality that does not require discursive signification. Such gestures force the police to display themselves as what they are: a criminal gang like any other, fighting for control over a territory.

If a destituent gesture forces power to return to Earth and show itself in its materiality, only to then be followed by a constituent process (of a strategy and a subject), it will likely send the conflict into a headlong crash with the forces of order, a tragic war that will be played out through a symmetrical confrontation in which the counterrevolutionary forces (the police) will direct all their overwhelming military might toward winning the battle.19 This is what happens to every movement that, upon hitting an impasse in its antagonism to the state, either enters into decline, or finds a core motivated to continually raise the bar of the clash until it becomes tragically military, closing any revolutionary glimmer, fossilizing the civil war into two consolidated fronts, with an adversary that, in addition to a military advantage, often also has the privilege of choosing on which ground the battle is to be waged.

We see these truths on display in the current cycle of struggles in France: on the one hand, the innovative capacity of the irruption to initiate a new compositional subjectivity, a capacity which, to the extent that it succeeds both in escaping a dialectical logic with the state and in continually reinventing itself in practical and rhythmic terms (i.e., in the temporal choice of actions), must itself be considered destituent. Similarly, if Earth Uprisings has displayed a great capacity to checkmate and debunk the police, this is due in large part to the innovative force that the new composition was able to produce. Yet this ability to produce new unexpected forms seems to have been reduced on the occasion of March 25, where the composition was instead rather consolidated and the strategy adopted similar to that of the previous date. The result was a series of choices that had become predictable by the police, who opted to await the arrival of the demonstration and initiate a "siege" dynamic allowing them to deliver a brutal attack on the crowd. The ensuing analyses of tactical errors in this case are certainly valid20; but to be able to break the impasse of March 25 will require a reformulation of the overall strategic hypothesis that led to the automatization and hardening of organizational capacity, preventing the movement from improvising and disorienting the other side, as during the previous October.

One hypothesis could be to aim for a broadening of the compositional process: in this regard, efforts to extend the reservoir struggle to an international plane have led, on the one hand, to raising the bar of the expectation for confrontation (an opportunity that the police did not fail to seize), and on the other hand, it can make it difficult to reformulate the tactical organization of the demonstration. When we look back historically, however, international meet-ups and campaigns to quantitatively grow a struggle have rarely succeeded in generating a qualitative leap; if anything, they often announce the descent and decline of the reality of struggles. By contrast, our hypothesis is that the strengthening and deepening of a struggle arises rather from the intensification of its compositional relations, or perhaps from their alternating decomposition and recomposition, which can produce new and unforeseen forms of improvisation.

Until March of 2023, the movement in Atlanta was able to maintain the initiative through a series of moves that almost always caught the police off guard. This is certainly because the movement's internal dynamics are extremely opaque, especially to the police, who are still groping in the dark after a radical leadership responsible for the most destructive actions, but also because every week of action has been different and highly improvised. During the "week of action" in March 2023, this advantage led the movement to raise the bar to a point that makes it difficult to imagine more incisive forms of direct action21; at the same time, the police were compelled to respond through a random roundup of bodies who were given the heavy charge of “domestic terrorism.” When, almost a month later, the city of Atlanta decided to strike a blow at the project, initiating the cutting of part of the forest and militarizing its surroundings, the movement avoided falling into the trap of reacting to the city’s move (which would have meant laying siege to the construction site); at the same time, attempts to attack elsewhere by decentralizing the conflict do not yet seem to have found effective forms, despite the good intuition (numerous actions "sanctioning" the realities involved in the Cop City project have been taken place all over the United States). At this point, the only available strategy is to push for exploding internal contradictions in the city's Democratic-led government through ever-increasing pressure on the mayor, exploiting the broad consensus enjoyed by the movement; however, this may shift the axis of the struggle beyond the capabilities of the movement itself. As some people who have long been active in the mobilization recognize, what could bring new life into the struggle is the involvement in the compositional process of new subjectivities, as has timidly happened in the case of the students who have occupied certain University buildings in Atlanta, or through the experimentation with practical forms that are able to bring about a qualitative leap from support to engagement by "citizens" hostile to the project.

When a movement can no longer defend itself (or attack), having exhausted its tactical resources, there is a risk of sliding back into political dynamics. Strategy begins to decline into representative forms of politics, tactical choices fall increasingly into performative forms aimed at intervening on a public and media level. What is happening in Atlanta, or in France (especially what recently happened in Val Maurienne), risks following similar trajectories to those previously observed in Italy’s No-TAV movement. The latter, facing its decline, began seeking refuge in representative politics, whether by trying to use "democracy," or simply by falling back on stunt activism in search of media coverage. In these moments, the “strategy of composition” no longer opens onto a revolutionary trajectory; instead, groups fall back into increasingly identitarian dynamics, and the more political ones begin to focus on building consensus and strengthening their position in the public eye, “capitalizing” the struggle. The strongly ethical-political tension at the base of the struggle gradually becomes replaced by a public-political dynamic. When politics become public the movement not only exposes itself to repression, it also risks losing its capacity to improvise and remain unpredictable.

A strategy of composition can "uncover" the revolutionary possibilities of a struggle only if it continues to remain open while pursuing a destituent trajectory: this means, on the one hand, maintaining an orientation of escape from any dialectical dynamic with power, and, on the other hand, subjecting the forms generated by the compositional process to continuous recombination and rupture. A recombination might take place, as in the case of the pension reform mobilization, through the irruption of a new protagonism that is difficult for power to decipher; or, in the case where the growing to accommodate new components in a struggle becomes difficult, by attempting to discover new configurations of encounter and contact between the subjectivities that compose it, while seeking out ways to desubjectivize itself so as to prevent a process of subjectivization from crystallizing.

Where no new forms or rhythmicity can be found, in cases where the capacities for experimentation have been exhausted, then we must learn to recognize when it has already begun its decline, at which point any voluntaristic attempt to revive it will only result in a form of sacrificial militantism, mirroring the power it seeks to combat. From a broader strategic point of view, such a sacrificial will can also result in a loss of the lessons that the struggle otherwise had to teach and transmit, the logistical, organizational and practical capacities that might otherwise constitute a key asset for a new phase of the conflict down the road.

In a word, the revolutionary possibilities of any given struggle depend upon its ability to create and sustain destituent power, through a process of negation and autonegation that regenerates itself through continuous experimentation and improvisation. Revolution is an alchemical art: it’s about casting gold, steel, and blood, generating new alloys, combining new strategies, in an endless heterogenesis.

June 2023

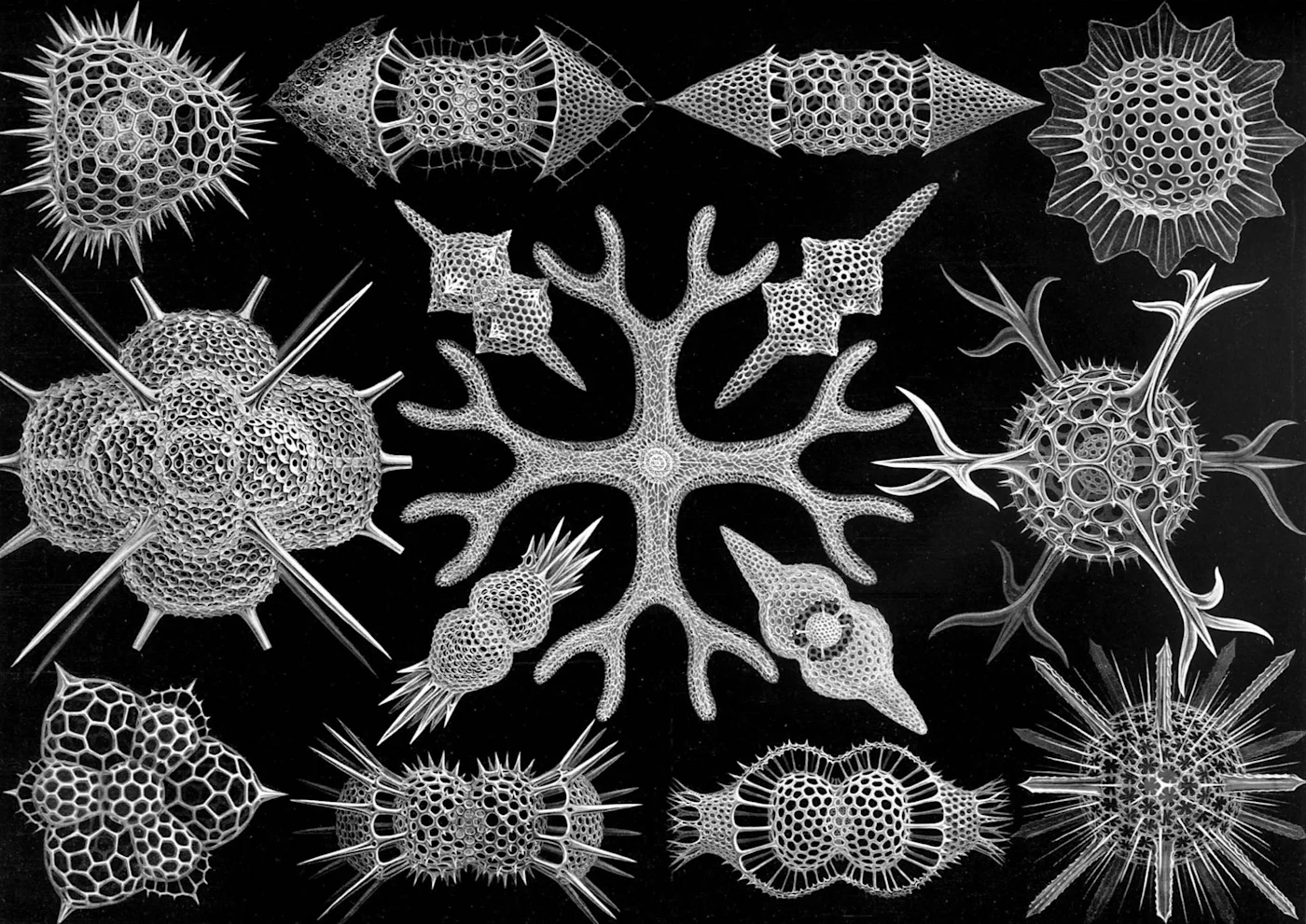

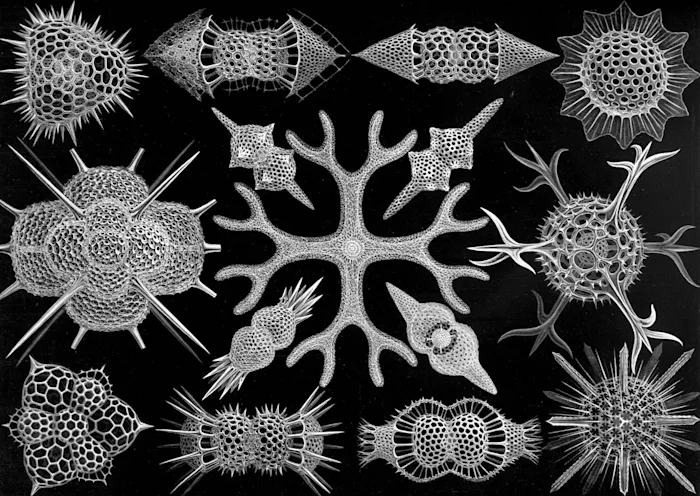

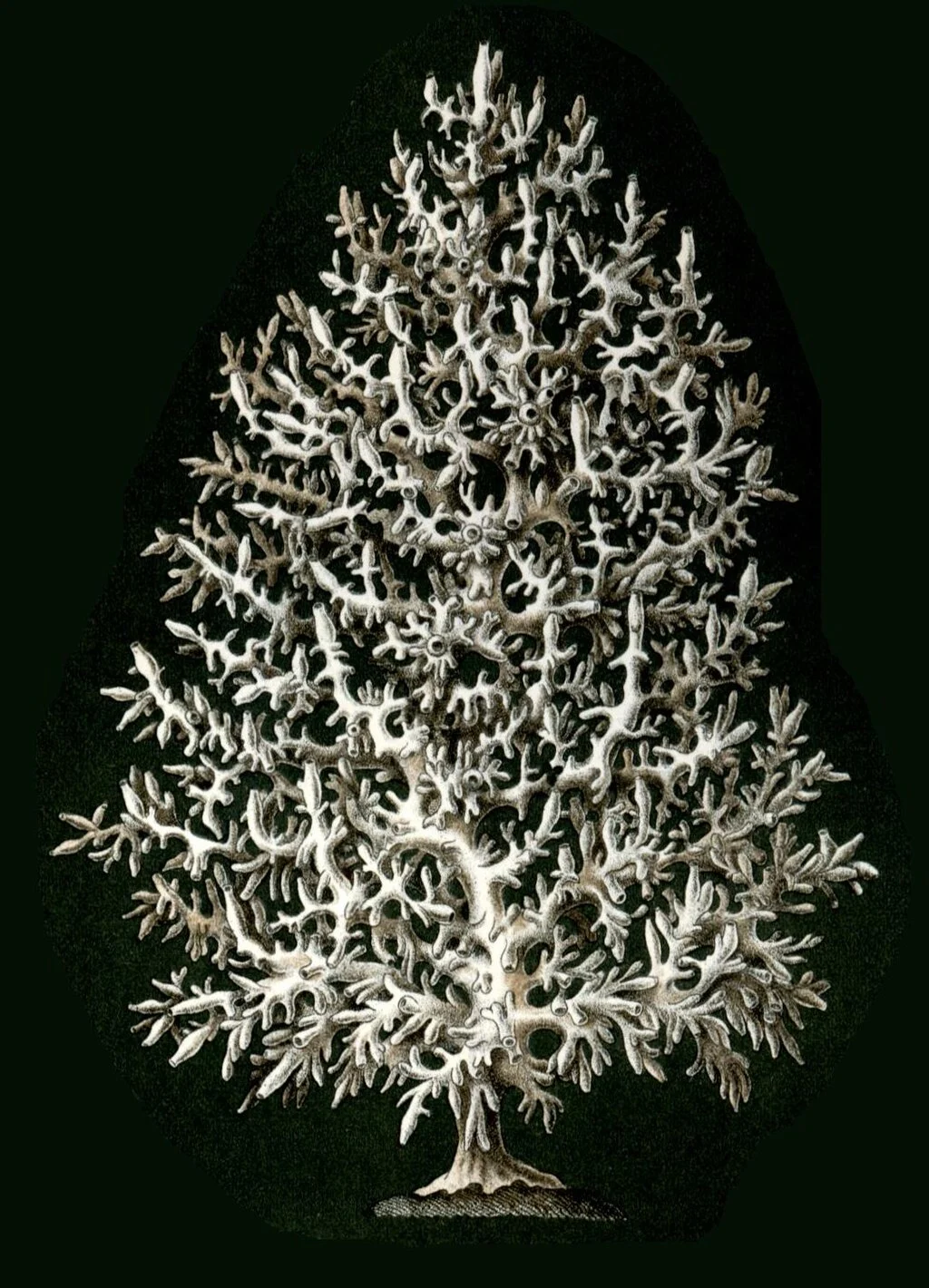

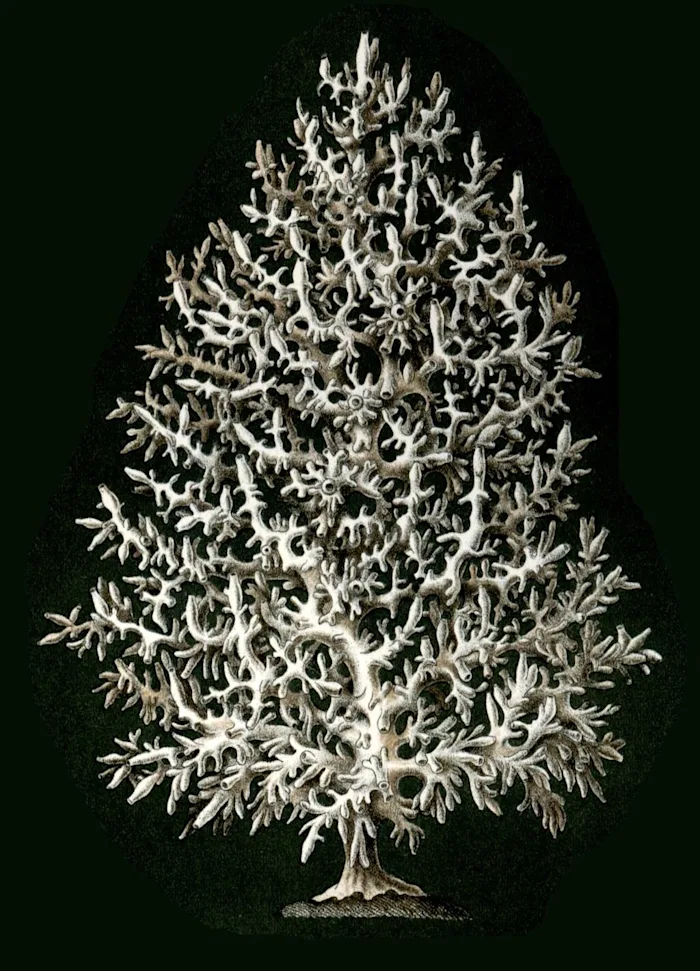

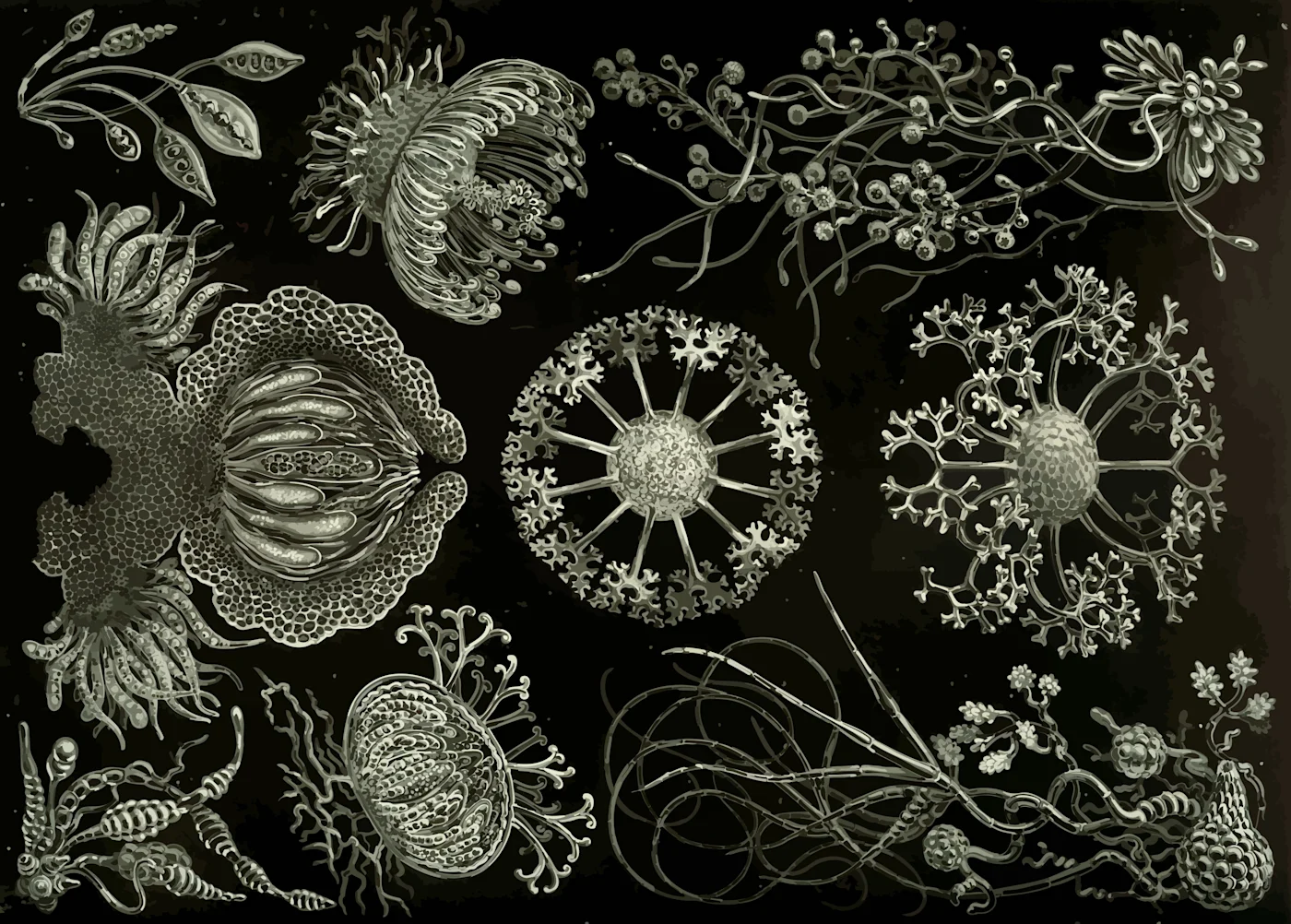

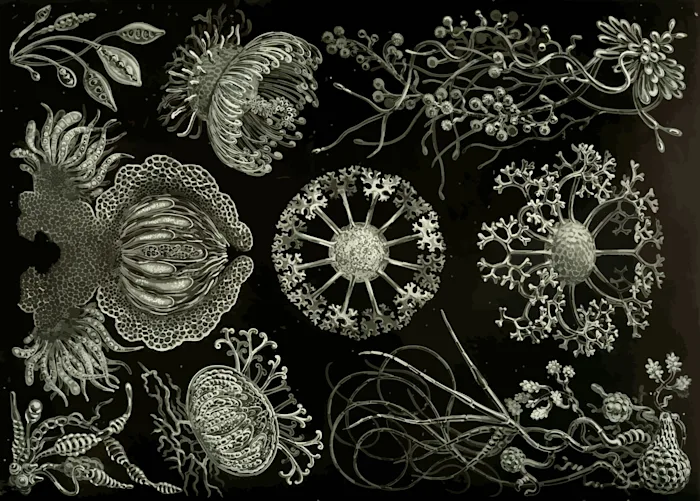

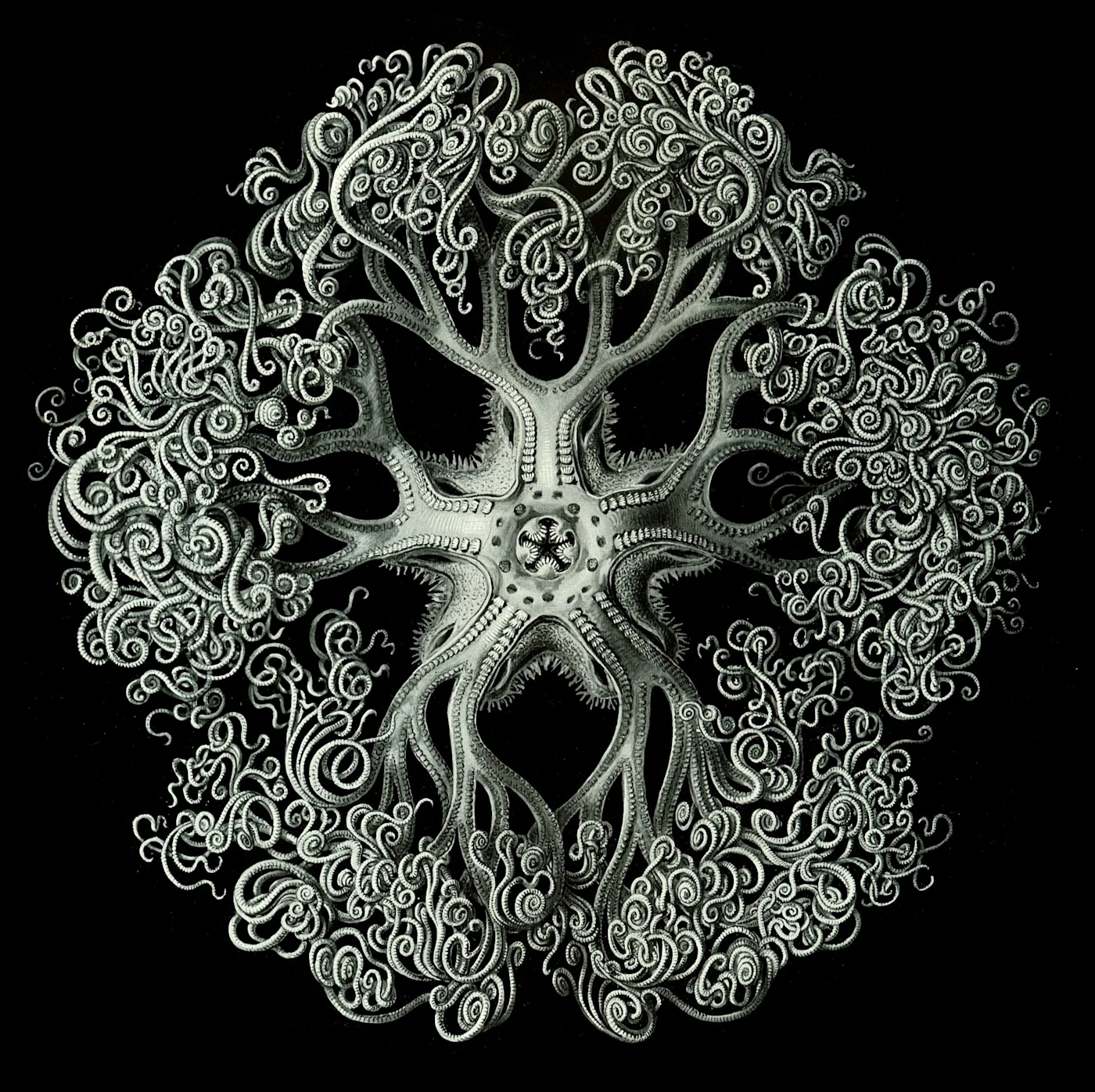

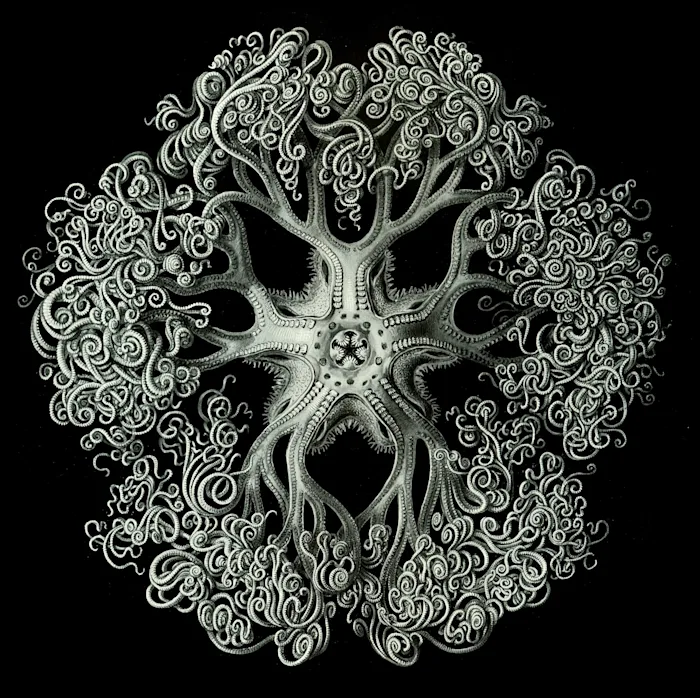

Images: Ernst Haeckel

Notes

1. Temps critiques, “La protestation en cours sur les retraites. Du refus à la révolte?” Lundi matin #377, April 4, 2023. Online here.↰

2. A literal translation would be "alloy-ance," a neologism formed by “alloy” (amalgamation of metals) and “alliance.”↰

3. See Endnotes, “Onward barbarians!” Online here.↰

4. Anonymous, “Sortir de l’antagonisme d’état,” lundimatin #378, April 11,l 2023. Online here.↰

5. Joshua Clover, Riot. Strike. Riot, Verso, 2016. The author refers in particular to the Oakland Commune.↰

6. The following two texts clearly trace trajectories in two significant experiences during the 2020s in the United States in Atlanta and in Seattle. Anonymous, “At the Wendys,” Ill Will, November 9, 2020 (online here), and Anonymous, “Get in the Zone. A Report from the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone in Seattle,” Its Going Down, June 9, 2020 (online here). ↰

7. On the relationship between administration and sovereignty, and how the Zapatista experience succeeds in breaking out of certain shoals of Western radical thought, see Jerôme Baschet, “Zapatista Autonomy. A Destituent Experiment?” Ill Will, September 7, 2022. Online here.↰

8. On this use of the term “autonomy” see Adrian Wohlleben, Autonomy in Conflict, in The Reservoir, Vol. 1. Online here.↰

9. From a subjective perspective, the emptiness left by the end of an uprising is often ethical and affective, first and foremost. This stands in contrast with other more nostalgic arguments indexed to the labor movement, which tend to highlight the political void left in its wake, and the absence of a reliable political Subject. See, for example, Maurizio Lazzarato, “The Class Struggle in France,” Ill Will, April 14, 2023 (online here), or more generally, his book Guerra o rivoluzione, Derive Approdi, 2022.↰

10. Hugh Farrell, “The Strategy of Composition,” Ill Will, January 14 2023. Online here.↰

11. In a recent text entitled “Tragic Theses,” the author argues that territorial struggles offer an example of an effort to overcome or undermine the separation between species, between the human and the nonhuman, by breaking down the processes of humanization and dehumanization that underlie the processes of Capital valorization. This hypothesis would seem to find confirmation in the slogans many of these movements tend to adopt — "We are the valley that defends itself" (No-TAV), or even the very name "Earth uprisings" — which point to a place, a territory, rather than to a Subject producing the agency within them. See Anonymous, “Tragic Theses,” Decompositions, March 9 2023. Online here.↰

12. It should be said that Earth Uprisings is actually something more than a territorial struggle; in fact, the entire organizational effort of its network has, in many respects, reflected an attempt at overcoming the limits of a specific and localized territorial struggle. In this piece, my focus is only on the specific case of the struggle against the mega-reservoirs in Sainte-Soline.↰

13. See Anonymous, “Pour ceux qui bougent (en 2023): 2016 dans le rétroviseur,” Lundimatin, February 14, 2023. Online here.↰

14. Adrian Wohlleben, “Memes without End,” Ill Will, May 16, 2021. Online here. ↰

15. On the complexity of this case, see Anonymous,“Victory and its Consequences,” in Liaisons Vol. 2. Online here. ↰

16. Bordiga scholars will hopefully forgive me this gross oversimplification of the distinction between historical and formal parties.↰

17. This expression is taken from Katherine Nelson, “The Anarchy of Power,” South Atlantic Quarterly, 122-1, January 2023. Following Reiner Schürmann, Nelson argues that the crisis of modernity brought with it the decline of metaphysical frameworks on which forms of power were built in the modern era. Nihilism has brought these frameworks out into the open, which, once unveiled, can only begin an inexorable decline. As a result, the matrix of our age is essentially nihilistic and anarchic. In the face of this decay, power no longer seeks a set of universal or totalizing justifications, as it tried to do throughout the history of Western modernity, but now redefines itself as pure force, violent domination. Michele Garau has reached similar conclusions in his recent work on Jacques Camatte (See Garau, “The Community of Capital,” Ill Will, April 23 2022. Online here). According to Garau, rights and all forms of the liberal state enter into crisis in the mid-twentieth century. The representations with which Capital had equipped itself to fill the vacuum created by the destruction of the communitarian ties that preceded it no longer represent a cohesive element, since economic relations have penetrated social relations and capital has become immanent to society itself, to the "social," and no longer need to produce a series of externalizations or transcendences of an institutional or value type that serve as the glue for a population of separated individuals. These are the theses that Jacques Camatte developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s and which, as Garau notes, were taken up by Negri himself in his 1972 text Crisi dello stato piano, in which the author defines bourgeois freedoms and the nation-state as no longer “parvences,” but double “parvences”: power is now random and arbitrary; money, having become total representation, becomes the form of domination of the social world and, losing all social reason for being, is based exclusively on class violence. The state then assumes a role that is no longer one of mediation, but of providing the political basis of domination for Capital.↰

18. Contrary to those who believe that the destituent hypothesis simply represents a proposal for further revolt and suspensions of historical time, the idea of a destituent power was in fact formulated by Agamben and the Invisible Committee precisely in an effort to chart a revolutionary trajectory that does not leave itself shipwrecked on the same rocks that have long turned modern revolutions into counterrevolutions.↰

19. In “The Anarchy of Power,” Nelson highlights some limits related to the translation of a destituent power into a counterpower: “A politics that refuses any claim to legitimacy can indeed, as the Invisible Committee writes, force the government to ‘lower itself to the level of the insurgents, who can no longer be “monsters,” “criminals,” or “terrorists,” but simply enemies,’ it may ‘force the police to be nothing more henceforth than a gang, and the justice system a criminal association.’ However, this runs the risk that the ensuing struggle will become a battle “to the death” between factions. In such cases, a short-circuited destitution becomes the broken metonym of meaningful political existence — producing casualties of an anarchic epoch. To be clear, such a deadly identification of what one is or what we are with what is to be done, of being and praxis, is not at all illustrative of destitution — yet it is the risk, I contend, that destituent politics uniquely and intrinsically harbors.”↰

20. See Les Soulèvements de la Terre, “To Those Who Marched at Sainte Soline,” Ill Will, April 24 2023. Online here.↰

21. An entire construction site was set on fire, as shown here. ↰