Crossing the Rubicon

S. Prasad

Building upon earlier analyses of insurgencies in Sudan, Sri Lanka, Kazakhstan, and elsewhere, S. Prasad argues that the 2025 protests in Turkey offer us a glimpse of the shape that the coming movements against autocracy in other countries might take. Recognizing this might allow us to anticipate the limits that similar unrest will need to overcome, including protests against Trump closer to home.

Other languages: Français, Türkçe

It is well-known that an automaton once existed, which was so constructed that it could counter any move of a chess-player with a counter-move, and thereby assure itself of victory in the match. A puppet in Turkish attire, water-pipe in mouth, sat before the chessboard, which rested on a broad table. Through a system of mirrors, the illusion was created that this table was transparent from all sides. In truth, a hunchbacked dwarf who was a master chess-player sat inside, controlling the hands of the puppet with strings. One can envision a corresponding object to this apparatus in philosophy. The puppet called “historical materialism” is always supposed to win. It can do this with no further ado against any opponent, so long as it employs the services of theology, which as everyone knows is small and ugly and must be kept out of sight. —Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History”

Despite our nostalgia, the comforts of “historical materialism” are no longer available. The worker’s movement missed its date with destiny over a century ago. It is no longer possible to have faith in a philosophical apparatus that is “always supposed to win.”

Once the system of mirrors and illusions that conceal the truth are gone, what is left is a game of chess. There is no master chess player that can always assure itself of victory in a match. But predictions, based on an appraisal of the positions of the pieces on the board, a knowledge of the rules of the game and a familiarity with its history, and an estimation of the style of play of the opponent, are possible. This is the basis of strategy.

Chess is a game of anticipation, prediction, and preparation. A chess player aims to plan several moves ahead. History resembles chess. But unlike chess, history is a game of both strategy and chance.

Ours are turbulent times. The temperature is rising along with the tide. Storms are coming. Rather than the certainty of theology, what our times might require is a science of navigation with which to sail the stormy seas. Weathering the coming storms, staying afloat and keeping our heads above water, sailing towards a horizon: these are the tasks of our times.

These tasks can be prepared for. This will require grasping the rhythm and dynamic of the historical movements unfolding today, as well as their spread and circulation, the impasses and limits that they encounter, and the contradictions that bring about their collapse, alongside the global economic and geopolitical turbulence that generates and transforms the conditions from which they emerge.

On this basis, some predictions can be made. The latter will never hold the theological certainty of “historical materialism.” But, however tenuous, they might allow us to set sail again, confident in our orientation.

Crisis of the crisis state

It has been said that there are decades when nothing happens; and there are weeks when decades happen. It will be left for historians to decide whether the first hundred days of the second Trump Administration were one or the other.

The innovations made during the course of imperialist wars tend to return, sooner or later, to the metropolitan core. This, after all, brought us canned food and the internet. The great leap forward of the Trump administration has been applying Donald Rumsfeld’s “Shock and Awe” doctrine to domestic politics. The flurry of executive orders are the heavy artillery with which Trump hopes to batter down all Chinese walls.

The opening months of this year have often been described in terms that seem to evoke the transition to a new epoch, rather than just a new administration. An essayist, writing in the pages of the New Yorker, suggested that we are witnessing the eclipse of what had been known as the “imperial presidency.” Instead, “Trump’s second Administration marks the high noon of the emergency Presidency.”1 T.J. Clark, the former situationist, has described this moment as simply “the spectacle becoming a state.”2 But as Debord reminds us, as the state becomes indistinguishable from the spectacle, “that state can no longer be led strategically.”3

There is perhaps no clearer image of the present than this: On the night of his inauguration, Trump sat at a desk, which was placed on a stage in a stadium packed with spectators, and signed executive orders in front of a live audience. This bombardment of executive orders will have deep and potentially long-lasting effects not only upon the global economy, but also on America’s moral and political standing in the world, and on the system of checks and balances behind one of humanity’s longest experiments in Republican government. Trump’s blitzkrieg has reduced nearly all of us to the status of spectators. How will it be possible to break this spell?

While there had been no shortage of writing discussing the urgency of the moment, the first hundred days of the new Trump administration saw little signs of resistance.

But then, suddenly, cracks in the spectacle began to appear. Crowds gathered to confront ICE agents during raids in San Diego, Chicago, Minneapolis, and even Martha’s Vineyards. In Los Angeles, this set off three days of riots.4 Protests began to spread to dozens of cities across the country.5 Night after night, there were demonstrations outside of courthouses and detention centers across the country. Protesters attempted to disrupt raids, blockade vans carrying detained migrants, or otherwise interrupt the machinery of mass deportations. In Newark, New Jersey, there was a riot inside a detention center. The mayor of the city had earlier been arrested there. A mayoral candidate in New York was arrested as well. The national guard was deployed in several states. Thousands, in total, were arrested.

The movement in Los Angeles, after the initial riots, has deepened, spreading to new neighborhoods and experimenting with tactics and forms of organization. But elsewhere, the movement has yet to reach a critical mass in terms of numbers or momentum. Protests are often contained to small areas of downtown and have rarely pulled in more than a few thousand participants. Most of the country is, for now, still resigned to the role of spectators.

An image of the future

What form will resistance take during the second Trump administration?

A herald from Istanbul carries the elements of a response. On May 1, 2025, thousands of protesters battled with riot police in an attempt to march on Taksim Square. Given that it was this same square that was the site of the Bloody May Day massacre in 1977, and the Gezi Park protests in 2013, the symbolism was lost on nobody.

Turkey is in the midst of the largest protest movement it has experienced since an occupation of Gezi Park in Taksim Square launched a nation-wide uprising in 2013. One of the questions raised by the current unrest is whether it is possible to reopen the vortex that was closed, in Turkey and across the globe, with the defeat of Gezi Park. In the decade since Gezi Park, Turkey has experienced a long drift towards authoritarianism. Turkey is further along in a process that many countries, including the United States, are now undergoing. A key distinction is that while Erdogan has stood over a slow drift, Trump has imposed a blitzkrieg pace.

Turkey is an image of the future. The events in Turkey offer us a glimpse of the shape that the coming movements against autocracy in other countries might take. It is already one of the clearest distillations of a trend happening around the world. This might tell us something about the economic conditions that create a context for unrest and the political moments that act as a trigger, the tactics and forms of organization that protest movements might employ, what their class composition might be, and how these movements might be shaped by the wider economic and geopolitical transformations happening.

With that in mind, the following offers an appraisal of the Turkish events. It then tries to place those events in the context of the global economic turbulence and the sequence of struggles that have been unfolding since the 2008 financial crisis. Then it places these protests in the context of the unrest spreading throughout the regions that surround Turkey, with an eye towards their shared limits and dynamic. In doing so, it attempts to ask under what conditions might a new global wave of struggles be possible?

One morning in March

It began on March 18 when the University of Istanbul annulled Ekrem İmamoğlu’s diploma. İmamoğlu had been mayor of Istanbul since 2019. He had twice defeated the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) in significant elections.6

It was presumed that the Republican People’s Party (CHP) would nominate İmamoğlu as their candidate for president. Recent polls showed İmamoğlu performing better than Recep Tayyip Erdogan in the coming elections. But the constitution of Turkey requires that presidential candidates have a college degree.

İmamoğlu was arrested the following morning. He was accused of corruption and supporting terrorism for having allegedly collaborated with the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) in local elections. CHP leader Özgür Özel declared this "a coup against our next president."7

“The move against İmamoğlu has thrust the country into political and economic turmoil,” according to the Financial Times.8 “It ignited a deep sell-off in Turkish assets that forced the central bank to sell billions of dollars of its reserves to defend the lira as it tries to cool inflation of about 40 per cent.”

On the day of his arrest, İmamoğlu received nearly 15 million votes in the CHP’s presidential primary election. This is far in excess of the actual party membership. Many non-members cast ballots in solidarity.9

A ban on public gatherings in Istanbul was declared. Riot police took up positions throughout the city. Streets were shut down and barricaded. But thousands of protesters gathered nevertheless at City Hall in Istanbul that night.

Protests began at the University of Istanbul, Imamoğlu’s former alma mater. Student protesters broke police lines, pushed through barricades, and poured into the city streets. This gave confidence to people throughout the city, who would soon join them.

The day after İmamoğlu’s arrest, protests spread throughout the country, becoming more intense the following day. That evening, CHP leader Özel addressed a crowd of hundreds of thousands outside City Hall. “There are very few examples in the world of how to push back an authoritarian populist leader with peaceful demonstrations and civil protest,” Özel declared. “This will be one.”10

But as Özel spoke, riot police fired tear gas and rubber bullets into the crowd. Protesters threw projectiles and attempted several times to break through a police barricade. A climax was reached the next day. A pattern soon took shape. Protests often began during the day on university campuses, during which students would fight through police in order to gain access to the city center. Crowds would gather nightly at Istanbul's City Hall. These gatherings frequently led to clashes with the police. Tensions emerged. Students and the opposition party became two distinct poles within the movement. A journalist remarked:

In his speeches to the crowds gathered in Istanbul, Özel has repeated Erdoğan’s refrain that “whoever takes Istanbul, eventually takes Turkey.” Erdoğan was elected mayor of Istanbul in 1994 and jailed in 1998 on the charge of inciting religious hatred. Four years later, he led the AKP to a landslide general election victory. He may see his own ghost in the figure of İmamoğlu.

Erdogan held a press conference. The protests, he declared, are a “movement of violence.” Later, he added: “Those who spread terror in the streets and want to set fire to this country have nowhere to go. The path they have taken is a dead end.”

After a week, the rhythm began to slow down. The CHP called for an end to nightly protests. Some continued in certain neighborhoods in Istanbul, but they were smaller and more heavily repressed. The focus instead turned to weekly mass demonstrations, which took place every Saturday in a different city, and every Wednesday in Istanbul.

Searching for a means to sustain the momentum, the movement began to experiment with new tactics. A boycott campaign was launched. At first, it targeted businesses associated with the government. Later, this was expanded to a total economic boycott: a “buy nothing” day. Both students and opposition parties have called for widespread consumer boycotts to add economic pressure to the mass demonstrations. But momentum for the boycott movement quickly fizzled out.

A second climax was reached with the clashes around Taksim Square on May Day. Protests have continued in the time since. But the movement, for now, lacks both a clear horizon and a means of building momentum.

I. Young Turks

Leaving the twentieth century

War has returned to Europe. There is skyrocketing inflation. Tariffs and trade wars. Refugee crises and mass migration. Red scares and repression on campuses. The rise of populisms left and right. Authoritarian strongmen casting their shadows over more and more of the globe.

At twenty-five, our young century has begun to bear a strong resemblance to its predecessor. The “end of history” prophesied by Francis Fukuyama has ended. But the “end of prehistory” foreseen by Marx is nowhere visible on the horizon.

Things move in cycles. All great world-historic events happen twice, although never in the exact same way. Historical analogy can only be stretched so far. The new authoritarians are not simply a revival of fascism. What has been on the rise is something different.

The populist strongmen who flaunt their illiberalism today, such as Putin, Orban, and Miliei, have largely been ushered into the halls of power through democratic elections. Once in power, they begin pushing the limits of the rule of law. Their opening moves often tend to be popular enough that they continue to retain the support of many voters. Over time, the limits on executive power, the systems of checks and balances, are eroded but not totally overturned.

There is, of course, a spectrum. On one end, there is Russia, Belarus, or Azerbaijan. These countries maintain the semblance of republican institutions. Elections continue to happen, but the opposition is designed by the president and he decides who is allowed to run against him.11 On the other end are Brazil and South Korea. There, would-be strongmen have launched coups that failed, and elections are still to some degree competitive.

Somewhere in the middle of this spectrum is Turkey. Turkey has been described as a “competitive autocracy” or “competitive authoritarianism.” In a recent interview with the New Yorker, Jenny White paints a clear portrait of this.12 Over the past decade, Erdogan has “solidified his control by eroding Turkish democracy” through “stocking the state bureaucracy with loyalists, co-opting the news media to limit negative coverage, and cultivating state prosecutors and judges to legally punish his foes.”

But this erosion has been incomplete. As White continues,

Still, most experts have not considered Turkey an outright autocracy, because many civil freedoms remain and opposition parties contest elections — and sometimes win, as they did in municipal races across the country last year. The question now… is whether Turkey will remain a mix of democracy and autocracy or shift significantly toward the latter.

This explains the stakes of the moment and the sense of urgency. In sum, although Turkey has been drifting towards authoritarianism for years, it had not taken the sudden leap that would push the situation past the point of no return. But Turkey is one of many countries experiencing this drift. The results of the uprising, whether it succeeds or fails, will have widespread consequences.

Drift

Over the past decade, the people of Turkey had been willing to tolerate this drift towards authoritarianism as long as it corresponded with economic growth and development. But when inflation began to spiral out of control, reaching forty percent in February, the country became increasingly disillusioned with the president and the ruling party. Rising frustration has made the electoral success of an opposition party more viable. This pushed Erdogan’s authoritarianism further, reaching a point of no return.

The events in Turkey seem to suggest that the American public will only tolerate the consolidation of executive power under Trump for so long unless his project leads, quite miraculously, to an economic turnaround. But it also could indicate that there might not be mass disruptive protests until the cost of living becomes nearly unbearable, legal options seem exhausted, and the administration does something which is seen as really crossing the line, thereby generating a situation from which there is no turning back.13

Things could change if events in Turkey (or elsewhere) take a turn. As the world becomes more chaotic, and as countries that are otherwise quite different drift along similar paths, new possibilities and paths of resonance open up. A dazzling breakthrough in Turkey could provide a glimpse of effective means of resistance in a time of economic turbulence and authoritarian drift. If this image resonates widely and begins to spread, that could shift the dynamic in America.

After the 2008 financial crisis, it took some years and several experiments before Americans arrived at a means of acting together against the austerity being imposed upon them. Importantly, they drew inspiration from breakthroughs elsewhere, notably from the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt and the movement of the squares that had begun to spread through Europe.14 The uprisings in the Middle East influenced the Occupy protests in America, which in turn influenced the Gezi Park protests in Turkey. Perhaps this time, the influences might flow in the other direction.

A qualification should be made here. Uprisings tend to result not from a stagnant condition of despair and disillusionment, but from rising expectations that have been thwarted.15 The protests in Turkey are about opposing Erdogan, the ruling party, and the slide towards autocracy more than they are an expression of support for Imamoğlu and the opposition party. Still, the conditions that made the protest movement possible are related, however indirectly, to the rising expectations, hope, and sense of possibility that accompanied Imamoğlu’s rise, and that now seem foreclosed.16 Similar conditions in the United States are more difficult to imagine.17

Colossal youth

Authoritarian strongmen often face a peculiar dilemma. Their rule, at times, corresponds with a period of political stability along with economic growth and development. This leads to the growth of an educated, urban middle class. But this young middle class then feels constrained by, and becomes increasingly frustrated with, the government that had made their emergence possible.18

As time passes, growth and development give way to inflation. In the popular imagination, the government becomes increasingly associated with corruption and economic mismanagement. Disillusionment grows and spreads beyond the urban middle class. This pattern has unfolded in a number of the countries that have had massive and successful uprisings in recent years, such as Sudan, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh.

According to Helen Mackreath in the London Review of Books, “in all the demonstrations [in Turkey], a younger generation — who have lived their whole lives under one-man rule — have been leading figures.”19

During the recent uprisings in Bangladesh and Serbia, students were able to provide a measure of cohesion, organization, and direction to the unrest as it spread across the country, pulling in a wide cross section of the population. A similar turn of events might happen in Turkey.

Echoing events elsewhere, the first demonstrations in March began on university campuses in Istanbul before breaking through police lines, spreading into the streets, and then converging at central locations in the city. Student protesters broke the spell and demonstrated the courage necessary to create a context in which many other layers of society would join the demonstrations. It was only after this that nightly protests outside of City Hall in Istanbul began.

In terms of organization and initiative, students have continued to provide a counterweight to the opposition party’s prominent position at the center of the movement.20 “We’re here for a demonstration, not a rally,” has been one of the chants of young protesters, marking a distance from traditional political parties. The youthful spirit of the movement is embodied in a mixture of reverence for the nation’s past and a sneering at nostalgia that verges on punk. As Mackreath notes:

At Saraçhane in Istanbul, close to the arches of the Roman aqueduct, the youthful crowd made its presence felt. They booed a leftist singer from the 1970s off stage in a show of impatience with a certain form of nostalgia.21

“But many also held banners of Mustafa Kemal,” she adds.22

The current movement, which began on campuses, has now found its way back to the universities: “Students at many universities have launched an academic boycott, refusing — along with some of their professors — to attend classes, and instead holding mass demonstrations.”23 By the end of March, the unrest had spread to high schools.24

While students and campuses have played a central role in the unrest, the focus on these elements risks obscuring aspects of the movement’s class composition. University and high school students have been at the forefront of the protests. But alongside them have been what we might call “working youth.”25 As Taylan Ekici argues,

Since the first day of the protests in various parts of the country, another segment has emerged that is 19-20-21-22 years old, who have not studied at university but are employed or looking for a job, this youth, who have been disconnected from education as a result of the pandemic and the distribution crisis that followed, act with a destructive and aggressive spirit wherever they go, and they are just as scattered and diverse, we have to take this segment into account in every statement we make from now on.26

“The capitalist mode of production itself has run out of future,” Theorie Communiste once declared, reflecting on the Greek riots in 2008. Their analysis of the Greek events invites comparison with the dynamic composition of the movement in Turkey this year:

[If] the instances of sharper social conflicts are concentrated on the precarious youth ... [this] is because “youth” is a social construct. It is here that the link between the student movement and the riots lies, and in a totally immediate way, it is the labor contract which summarizes this link. The crisis constructs and then attacks (in the same movement) the category of “entrants” depending on the modalities of their “entrance”: educational training, precariousness (and those who are in a similar situation — the migrants). ... It is the crisis of reproduction as such that annihilates the future and constructs the youth as the subject of social protest. ... The crisis of financialized capital is not simply the setting, the canvas, the circumstance underlying the riots in Greece: it is the specific form of the capitalist mode of production running out of future, and by definition it immediately places the crisis at the level of reproduction.27

Salad days

There is a tension between organization shaped through the experience of struggle and the eternal sunshine of youth. Serbia has experienced recurring waves of protest over the last decade. But the protests that began in late 2024 have been larger and have managed to sustain their momentum for longer. “The reasons for this,” Lily Lynch argues, are due in part to “generational” factors: “the Serbian youth does not have the war trauma of the older generations, nor the cynicism of millennials who came of age in the post-Milošević era, and for whom the word ‘democracy’ connotes disappointment and Western meddling.”28

The events in Turkey appear similar. At the forefront of today’s protests are youth that remember Gezi Park but were too young to have experienced firsthand the defeat and despair that followed. A passage of time allowing for a generational passing of the torch might have been needed in order for a new period of unrest to begin in Istanbul. Remember that between the 1905 and 1917 revolutions in Russia was the famous “twelve year lull.”

Such is the beauty of youth. There are times when advances can be made only by those who are not aware of the failures of the past and have not yet themselves been humbled by experiencing the taste of their own defeat. The naiveté of a life that has not yet encountered its limits, and remains unaware of what cannot be done, forms an historical necessity.

But this green youth will not last forever. Youthful enthusiasm has its downsides. It should be noted that the revolutionary student leaders and militant organizations that stood at the forefront of the unrest in Bangladesh last year, or Chile in 2019, were shaped by over a decade of waves of unrest. Nothing in Turkey over the last decade seems comparable.

A certain amnesia might be necessary to spark collective action. But then experienced militants and militant organizations forged during previous waves of struggle can act as vectors of intensification. In this way, although the passage of time may be necessary for new waves of unrest to emerge, the memory and experience of past struggles is still needed for new movements to succeed. Although we are hesitant to write recipes for the cookbooks of the future, any recipe for success would likely require pairing these two ingredients at a certain ratio.

Geopolitics of mobilization

Revolutions often follow military defeats. Consider 1871, 1905, 1917, or 1974. This was the logic behind what was once called “revolutionary defeatism.”29 The events in Turkey emerge from nearly the opposite circumstances. Behind the backs of the protagonists of these events is a transforming regional balance of power. The unrest reflects, albeit indirectly, Turkey’s new position of geopolitical strength.

After the fall of Assad, Turkey has emerged as a kingmaker in Syria, and a dominant political force throughout the surrounding region. The Trump administration has made clear that it has little interest in criticizing allies of America for drifting away from liberal democratic norms. Trump, in fact, praised Erdogan as “a good leader” in the days after İmamoğlu’s arrest.30

Europe is in no position to leverage any criticism against Erdogan either. Now that America appears to be winding down its military commitments to its allies in Europe, the continent sees itself as increasingly reliant on Turkey, which has the second largest army in NATO. Europe has already been leaning on Turkey to contain the flow of migrants to the continent. Turkey has maintained diplomatic relations with both Kyiv and Moscow, giving it an important role in mediating negotiations (as previously during the Syrian Civil War). As CHP leader Özel declared back in March, “unfortunately, the current global context — Trump, Putin, the war in Syria — has turned Erdoğan into someone other leaders want to bargain with.”31

On the other hand, the perception that Erdogan appeared weak in his handling of the Israeli invasion of Gaza has contributed to his growing unpopularity.32 Israel’s intensification of the war in Gaza and its incursions into Syria might have exacerbated this.

For now, however, Erdogan appears to believe that he is untouchable and that he has a free hand in acting on domestic politics without the risk of foreign interference or criticism. Yet as Steven A. Cook notes in a recent article for Foreign Policy, “in his hubris, he seems to have miscalculated how Turks would react….He may not have believed that Turks would turn out en masse to oppose Imamoglu’s arrest, but that is what they have done.”33

It is still possible that Erdogan has placed the right bet. Faced with a whirlwind of economic turbulence and geopolitical turmoil, and after years of chaos resulting from wars and revolutions, world powers are anxious to maintain order. Consequently, they have an interest in supporting any leader who appears to be a guarantor of stability in a troubled region.34

Exhaustion

Erdogan seems to expect that he can simply wait out the unrest, that the movement will eventually exhaust itself and people will move on. The next presidential elections are not until 2028.35 A lot can happen before then.

There is a chance that the economic instability works out in the ruling party’s favor. Erdogan and the ruling party appear to expect that people will soon return to worrying about inflation and the dwindling value of the country’s currency, rather than about free speech and democracy.36 The economic concerns that led people into the streets might later lead them back to their homes. Perhaps the economic chaos can be contained before people return to the polls in a few years.37

The Kurdish parties were hesitant to call people into the streets. Just weeks prior to the arrest of Imamoğlu, peace talks were initiated, and are still ongoing. This puts the Kurdish parties, who are anxious not to sabotage the negotiations, in an awkward position. The major Kurdish parties, such as the DEM, have begun to mobilize for the massive weekly demonstrations organized by the CHP.

This is one of those moments where history repeats itself. World-historical events happen twice. A similar set of circumstances created the backdrop for the Gezi Park unrest. Then as now, a new round of peace talks made the Kurdish parties anxious about mobilizing their supporters for the wave of anti-government protests.38 But there is also a longer story behind this.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk founded the CHP, which has historically been the standard bearer of secular Turkish nationalism. Building the Turkish republic came at the expense of Kurdish national ambitions. Kemalist generals were at the forefront of the waves of dirty wars against Kurdish rebels.

Ultra-nationalist groups have been visibly active in recent demonstrations. But even the liberal wing of the Kemalist party has not been very sympathetic to the Kurdish cause historically. Some collaboration between the CHP and Kurdish parties, such as the DEM, has occurred more recently in local elections. This, of course, is the basis of one of the accusations leveled against Imamoğlu.

Erdogan’s gamble is aimed at dividing the Kurdish population as a voting bloc. Pulling some of the Kurdish population towards the AKP would undermine the long term viability of the CHP as an electoral party. This realignment might be necessary if Erdogan is to win elections for another term as president.39

A key limit of contemporary struggles has been their inability to overcome the reigning separations in the societies from which they emerge. Erdogan has been perceptive enough to absorb this into his own strategy for statecraft. The recent announcement, after a historic congress, that the PKK plans to disband and disarm shows that, once again, Erdogan may have placed the winning bet.

Iron maiden

Erdogan has weathered storms before. These have included Gezi Park and a 2016 coup attempt. There is no reason he could not do so again. (Although the spread of demonstrations to AKP strongholds early on has been a promising sign.)

Still, until last year, the same could have been said about the “Iron Lady” of Bangladesh, former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. Their careers mirror each other in many respects. Both were the dominant figures in their respective political scenes for most of the 21st Century. Both were seen as respected global leaders who were responsible for their country’s rising economic and political stature.

During this time, for both Hasina and Erdogan, their tenure was, at first, associated with massive economic growth and development — what had been called an “economic miracle” — and for the expansion of democratic norms and the rule of law. But this was followed by long economic downturns, rising corruption, and a drift towards authoritarianism.

Hasina too had weathered her share of storms. She survived assassination attempts, political upheavals, and waves of labor unrest. Yet until a year ago, her grip on power had seemed all but unshakeable.

Things then changed quickly. Student protests began on university campuses in Bangladesh last summer. This was just after the Student Intifada, which began in universities in New York City and then spread to college campuses across the country and then around the world.40 Protests similarly began on the campuses of prestigious universities in Dhaka, the country’s largest city, and then spread outward across the city and country. This time, however, the focus was more local. The protests were initially focused on an old labor quota that reserved a certain percentage of government jobs for the families of “freedom fighters,” people who had participated in the country’s war of liberation against Pakistan in 1971. Many saw this as a means for the ruling party to extend patronage to their supporters. Qualified students and young people felt shut out of civil service positions that promised job security and upward mobility.

The protests built momentum. Attempts to shut them down by police, security forces, and supporters of the ruling party were seen as heavy handed, drawing still more people into the streets. A state of emergency was eventually declared, the military was called into the streets, a curfew was enforced, and the internet was shut down. During this time, thousands who had participated in the protests were arrested. The country was brought to a standstill.

Once again, the repression backfired. As soon as the curfew was lifted, protests started up again. More and more of the country poured into the streets. People were outraged by the scale and severity of state repression, but also used the occasion to express their own frustrations with the increasingly authoritarian government and the economic downturn.

The protest movement soon became a mass uprising. Demonstrators began calling for the fall of the regime. The armed forces were again called into the streets. But this time, soldiers refused to fire on the crowds. Fraternization with soldiers took place at the barricades. (A key moment in any revolution). Before long, as crowds pushed through police lines and marched on the presidential palace, President Hasina was forced to flee the country and resign from exile.

Crossing the Rubicon

“He has crossed the Rubicon,” a former AKP MP said. “There is no going back from here for him.”41 Soon after the arrest of Imamoğlu, a columnist for Foreign Policy charted out the possible routes that could be taken from here: “Whatever the outcome, it is not going to be pretty.”42

Erdogan could manage to hold onto power. In that case, repression will increase. It will reach a new scale, as it did after the previous crises Erdogan managed to survive. The culture wars within Turkey will escalate as a pretext for this. Foreign Policy paints a picture of this scenario:

Imamoglu will not be the only politician in legal jeopardy. And much like after the Gezi Park protests, Erdogan and his advisors will seek to further divide Turks, emphasizing who is authentically Turkish — those who support the president — and those who are not. This will only deepen Turkey’s culture wars and provide justification for ever-increasing coercion and forces against Erdogan’s opponents. Think of Erdogan’s post-failed coup purge of 2016, but worse.43

The alternative is not so simple either. The protests could escalate until Erdogan is toppled. Otherwise, the success of the movement could be measured by Imamoğlu or another opposition candidate defeating Erdogan in the polls. In either case, the country will be left with state institutions and a media landscape shaped by Erdogan, a mass party, and a large base of loyal constituents. The results of a successful uprising (or even electoral reform) could be chaotic:

If Erdogan leaves — and here I am reserving judgment about how the Turkish president might go — the victors will have to contend with political and social institutions that have been bent, shaped, and leveraged to aggrandize the power of Erdogan, the AKP, and the extensive list of constituents who benefited greatly from the Turkish state over the last two decades and have much to lose. Even if Erdogan were out of the picture, they would try to use the levers of power to defend themselves and undermine a transition. At the very least, it will be messy. There is a decent chance such a moment could turn violent, however. Since 2016, Erdogan and the AKP have been arming cadres of loyalists.

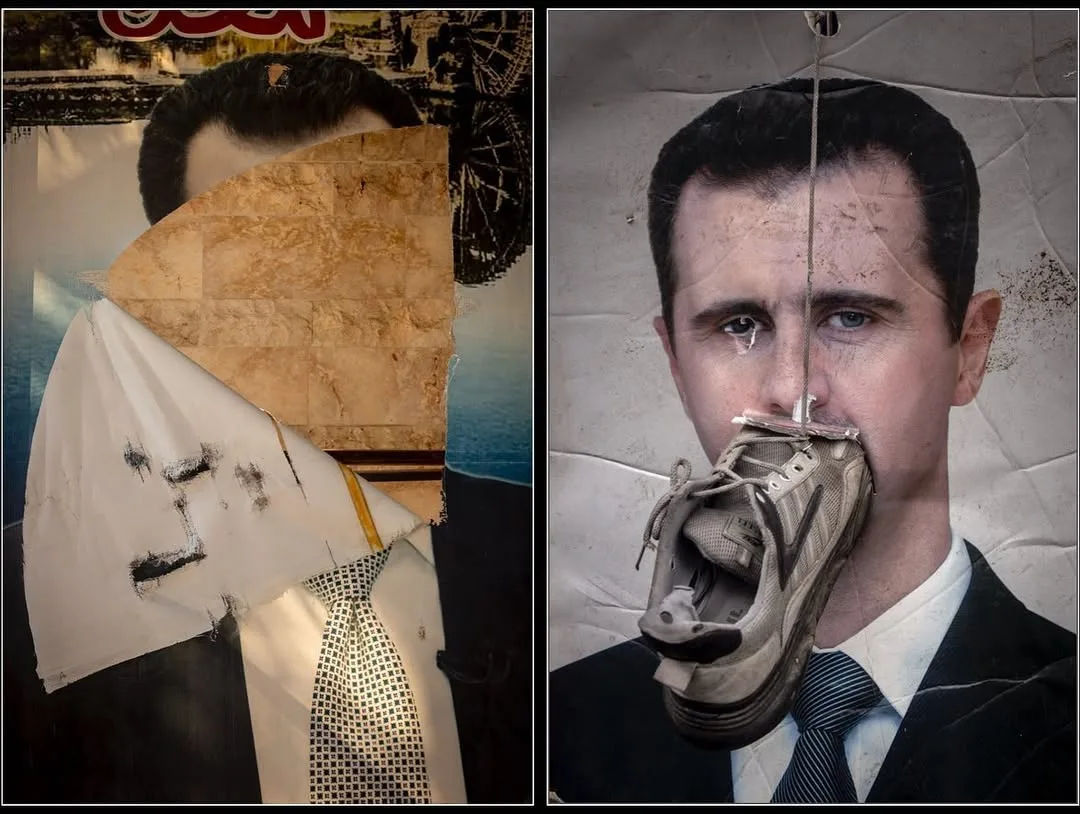

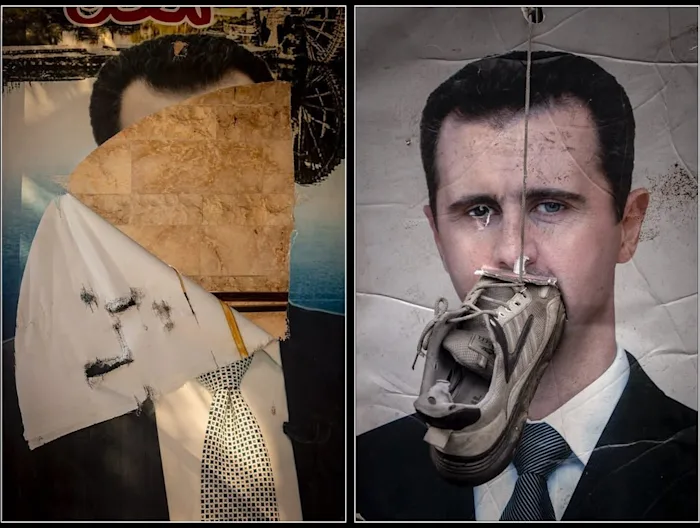

The latter conjures nightmare images of the civil war that dragged on for over a decade in neighboring Syria. But even recent uprisings in the that did not lead to prolonged civil wars nonetheless resulted in an increased political instability:

And therein lies the problem for Turks and others who… have dared to imagine what life after Erdogan may look like. The Turkish president’s departure may not necessarily augur better days. Indeed, things can always get worse. Just consider, for example, the chaos that Egypt plunged into after Hosni Mubarak’s ignominious end. With all the excitement among Turks and others about this “now or never” moment, Turkey is likely entering a period of sustained political and social instability — whether Erdogan remains in power or not.

There are plenty of reasons to be cautious. The last decade and a half of mass protests have provided ample examples of just how much chaos an uprising, whether successful or not, can unleash, particularly in the Middle East.

But Egypt and Syria are not the only possible paths. Revolutions in South Asia in recent years that shared many similarities to the uprisings of the Arab Spring led to remarkably different results.

A mass uprising toppled the Rajapaksa regime in Sri Lanka in the summer of 2022.44 As protesters stormed the presidential palace, Gotabaya Rajapaksa was forced to flee the country and resign from exile. After some weeks of uncertainty, parliament appointed the former prime minister of the old regime to lead a new government. Order was soon restored in the streets. The occupied government buildings and the encampments that resembled Egypt’s Tahrir Square were soon cleared by the army and police.

This outcome might not have been what Sri Lankan revolutionaries aspired to. But it was not a descent into chaos. Nor did it lead to a dictatorship. There was no military coup or civil war. And, more recently, a Marxist was elected president.

When protests began in Bangladesh last summer, similar concerns could have been raised about the fate of that country as are now being raised about Turkey. The political and social institutions of the country had been shaped by the time Hasina had been in power as much as the ones in Turkey have been shaped by Erdogan. The ruling party had a large and loyal base of supporters that benefited from patronage networks. The demands of the movement itself were a direct assault on the ruling party’s clientelism. These constituents had something to lose, and it was reasonable to assume they would defend it.

The situation got violent. Supporters of the ruling party attacked protesters. Police and paramilitaries fired onto the crowds. A state of emergency was declared. Martial law went into effect. The internet was shut down. There was sweeping repression and waves of arrests.

But this pushed things too far. The repression mobilized more and more people and made the regime increasingly unpopular. The armed forces sided with the crowds. The prime minister had to flee the country.

The ruling party and the military were both unwilling to risk civil war or the scale of bloodshed that repression would have required at this point. In the time since the uprising, there have been efforts by supporters of the old regime to stir up chaos and undermine the transitional government. But these have so far been ineffective and contained.

Bangladesh was able to learn the lessons of the revolution in Egypt. After the fall of the regime, the military announced that it would form a transitional government, a move that was blocked by the revolutionary students. The revolutionaries then appointed the cabinet of a temporary government instead.

Often, after an uprising brings down the government, there is a rush to hold new elections.45 This ensures that the deck is reshuffled without the institutions of power changing and that revolutionaries do not have the time to spread their ideas and form their own parties.

Before calling elections, the revolutionaries in Bangladesh set about remaking the existing political institutions, purging them of any vestiges of the old regime. This process has involved both using the power of the transitional government and direct action protests. This created time for new parties to be formed.46

It is too soon to evaluate the results of this process. It is possible that the next elections, which would be the first after the uprising, will not be dominated by parties of the past. Unfortunately, this is not the most likely outcome.

Every revolution has its moments of chaos or reaction. The fall of the Hasina government was followed by the spread of sectarian and antisocial violence. How widespread this was is subject to debate. The revolution has also given a new lease on life to militant Islamist parties.

The future of the revolution in Bangladesh is still uncertain. But it has so far avoided the fates of the Arab Spring countries. There has not been a military coup or civil war, and Islamists have not come to power. The country has not plunged into chaos, nor has it returned to autocracy.

Bangladesh and Sri Lanka illustrated that the results of a revolution can not be known in advance. It is possible, in some circumstances, to navigate through the stormy seas without crushing into the reefs on which the revolutions of the Arab Spring were shipwrecked. But the revolutions in South Asia will almost certainly encounter new limits and impasses. It will be the task of the next wave of revolutions to find a way beyond these.

Defeating the deep state

The theory of the state is the reef on which the revolutions of our century have been shipwrecked. The dual state has been a key challenge for uprisings throughout the world. Revolutions manage to bring down the government; but then the military either seizes power in a coup or sets limits on what the new government is capable of doing. This leads to a continuity between the old regime and what replaces it.47

Turkey has a certain advantage over Bangladesh or Egypt. In the latter countries, the armed forces function as a state-within-a-state, and are capable of acting as an autonomous political force. The military controls a substantial portion of the economy as well.

The armed forces in Turkey have a similar history of acting as an independent force in public life. The military has seen itself as the guarantor of secular Turkish nationalism, Kamal Ataturk's legacy. “The country’s powerful generals were the ultimate Kemalists,” Christopher de Bellaigue wrote in the New York Review of Books in the aftermath of Gezi Park:

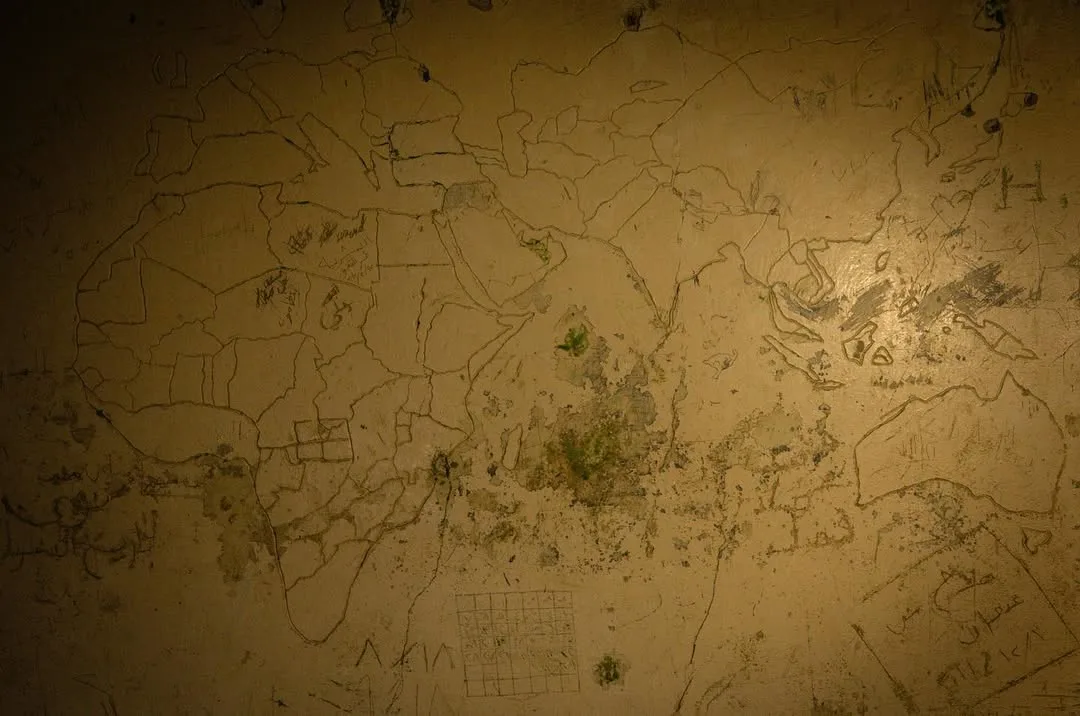

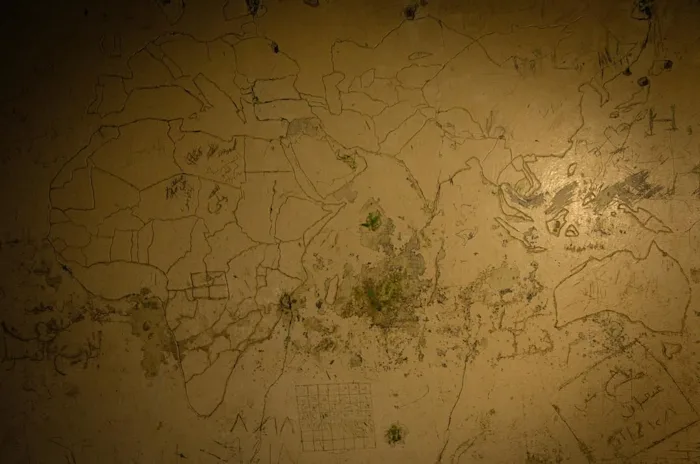

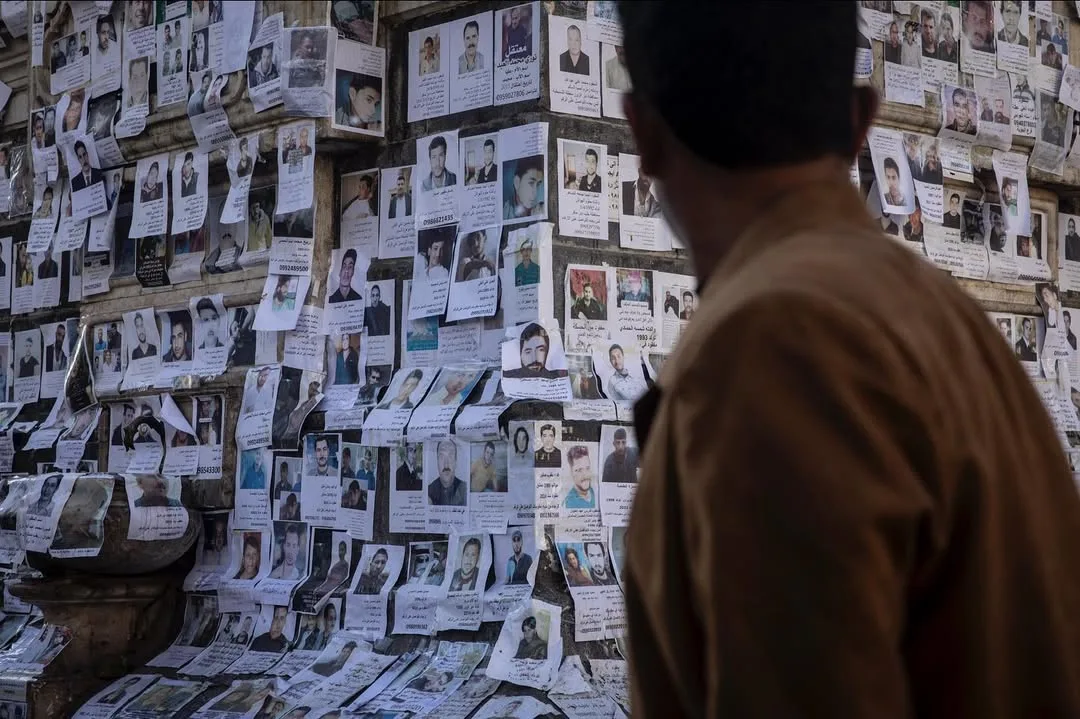

They kept the elected politicians to heel by using the threat of a military coup. (The army overthrew four governments between 1950 and 1997.) All the while, a dirty war against Kurdish rebels fostered a sense of beleaguerment that excused human rights abuses. Torture, miscarriages of justice, state-sponsored assassinations—Turkey was a leader in all.48

The rising power of Erdogan’s “post-Islamist” AKP led inevitably to tensions with the secular nationalists, concentrated in the armed forces. Erdogan clashed with and eventually managed to tame the Kamalist generals during his first decade in power. De Bellaigue continues:

[T]he AKP pushed through important pro-democracy reforms. Torture and extrajudicial executions declined. The dirty war lost intensity as Kurds were granted some cultural rights, and Kurdish nationalists, long denied parliamentary representation, became a voluble presence in the Ankara assembly. All the while, the army was being stripped of its political authority, a process that concluded…. [in August, 2013] with the jailing of dozens of retired officers, including a former chief of the general staff, on charges of plotting against the government…

It was widely expected the armed forces would regain the initiative and manage to reassert control over the country. But Erdogan managed to get the best of them: “The army fought several unsuccessful rearguard actions, including a threat—empty, as it turned out—to launch a coup in 2007, but the secular rebellion that some had anticipated didn’t happen.”49

During the Gezi Park uprising, rumors spread that the army intended to intervene on the side of the protests. This did not pan out.

The failed military coup of 2016, and the wave of repression that followed, was the final nail in the coffin. The Kemalist generals were defeated; the deep state was overcome. The threat of a coup would no longer be an effective means of keeping politicians in check.

There is a certain irony here. An expansion of the rule of law and of democratic norms and freedoms was required for Erdogan to stay in power early on. It was necessary for Erdogan to take on the deep state. But this is what made the authoritarian drift possible later on.

Uprisings in Turkey might have a longer path to success. The reigning-in of the armed forces might be one reason for this. The intervention of the armed forces was a decisive turning point in forcing the leaders of the old regimes to resign in Egypt, Sudan, and Bangladesh. The armed forces having an independence of action made this possible.

But if Erdogan ever falls, the dismantling of the armed forces as an autonomous force may turn out to be the biggest gift that he could have bestowed on his successors. The revolution in Turkey, whenever it comes, might have more breathing room. It might not take place within the constraints imposed by the armed forces or under the threat of a military coup.

Perhaps this is the secret of the authoritarian drift. By defeating the deep state, the autocrats of today might be accomplishing the tasks that the revolutions of our century have so far turned away from. These strongmen, then, might be preparing the way for the proletarian revolution, thereby, perhaps, digging their own grave.

Organized noise

Alluding to Goethe’s Sorcerer's Apprentice, Marx once compared bourgeois society to a “sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells.”50

Among bourgeois parties today, a similar anxiety has caught hold. The struggle against democratic backsliding seems to require that broad masses of the people are mobilized into the streets and that the normal everyday functioning of society and the economy is brought to a halt. But the weapons with which competitive authoritarianism is felled to the ground could be turned against bourgeois society itself. “[N]ot only has the bourgeoisie forged the weapons that bring death to itself; it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons — the modern working class — the proletarians.”

Protests are only effective by being disruptive. In order to accomplish anything, this disruption must spread. As struggles become more intense, new groups of people are pulled in, and new tactics emerge. But as struggles escalate and generalize, their aims often change. Once enough momentum is built, whatever initial demands set the struggle in motion are stripped away. What is left is the universal demand: the fall of the government.

If the only aim of the movement was the release of Imamoğlu and the possibility of the CHP competing in elections, this would still require pushing forward and leaping into the unknown. But this comes with a risk, namely, that the protest movement might spiral out of control and no longer be led by the opposition party (or anyone else, for that matter). This is a real risk with potentially significant consequences, Brazil in 2013 has shown.51

Still, it is obvious to everyone that the movement in the streets wants something more than this. The current protests are against Erdogan more than they are for Imamoğlu. But the arrest of Imamoğlu, the popular mayor of Istanbul and CHP candidate for president, sparked the unrest. The CHP has thus been at the forefront of demonstrations and a leading voice of the movement, as well as one of the most organized forces within it.

The CHP was pushed into this role. Protests began on university campuses. Students pushed through police barricades and marched into the city. It was only after this that protests outside of Istanbul’s City Hall began happening night after night. This set the stage for the CHP. Student protesters dragged the opposition party behind them each step of the way.

Once it entered the stage, the opposition party accepted the role assigned to it. Party leader Özgür Özel, in particular, rose to the occasion and played his part well, with a vigor and passion that is almost surprising. “After Mr. Imamoglu’s arrest,” Özel, according to The New York Times, “took up residence in a room in City Hall with a small bed to coordinate the party’s response, delivering fiery nightly speeches to the protesters.”52 Özel read the room, and saw the writing on the wall. The rhetoric of his speeches has captured the urgency of the moment and the dramatic mood in the streets.

That the opposition party took on this role is understandable, but it comes with certain risks. Parliamentary parties are often anxious about letting the genie out of the bottle, unleashing a force that might not be easily contained. These parties tend to view disruptive activity with distrust unless it is contained within their own patronage networks. (Even this can quite quickly spiral out of control, as recent events in Haiti have shown.53) Their attitude recalls Goethe: The spirits that I summoned / I now cannot rid myself of again.

This is a key distinction from Gezi Park and the movement of the squares. As a journalist noted at the time of the 2013 protests in Turkey: “Thus far, no opposition party has sought to claim the protests as its own. There have been no party flags, no party slogans and no prominent party functionaries to be seen.”54 In the time since the defeats of 2013, movements have become more political. The movement of squares led to the generation of a number of new parties, and traditional left and liberal parties have oriented more towards social movements.55

It could be said that anti-autocratic protests lend themselves more to the active participation of political parties than anti-austerity movements. There are two sides to this. The commitment of opposition parties might contribute to mass mobilizations earlier on; but this puts those parties in a position to act as brakes on the intensification of the movement.

Following just over a week of protests, the opposition party announced that the nightly protest outside of Istanbul’s City Hall would end. Instead the CHP called on the country to join a boycott of companies that were aligned with the government. But pressure from below once again pushed the party to go further. The protests would continue, the CHP announced, now with an emphasis on weekly mass demonstrations.

Is it possible to prevent an uprising from becoming absorbed into conflict between two factions of the Party of Order? This might require an orientation towards the spread and escalation of disruptive tactics, and an effort to defend the space opened up by this disruption and the potentials contained within it; in short, a party of disruption.

This is, in part, a matter of organization. For struggles to break through their present impasses, Idris Robinson has argued, a “paradoxical ordering of disorder” will be necessary. In a nod to Pharoahe Monche, he calls this an Organized Konfusion. An older term for this would be “the party of insurrection.” According to Robinson, “insurrection will involve precise coordination from within the constellation of riots.”56 Yet, even short of an insurrection, mass struggles require some degree of coordination. We might call the forms of organization proper to the coordination of spontaneity Organized Noise.

The success of an uprising requires the spread of disruption. New forms of organization often emerge from within these movements as a means to coordinate the spread and intensification of disruptive tactics. These can range from open and casual to more formal structures. During the Gezi Park protests, there were open assemblies and various working groups. The occupation itself was a space that made many forms of self-organization and coordination possible.

The July Revolution in Bangladesh was led by a coordinating committee of student representatives from across the country. The movement was able to maintain the initiative and set its own rhythm. But it was able to adjust its pace when confronted by changing circumstances. This made it possible to make intentional decisions to shift tactics and slogans as needed and to articulate a clear perspective even as the unrest spread far beyond the student milieu.

During the unrest in Bangladesh, the opposition parties were kept at a distance. This is related to the different circumstances that sparked the unrest. The initial concerns were about student frustrations with a job quota system, rather than the arrest of an opposition politician. But the militant organizations that emerged from within the movement that were able to take initiative and articulate clear positions made it much more difficult for any opposition party to position itself at the forefront.

The dynamic in Serbia has been similar, according to Lily Lynch:

The students have been careful to avoid association with Serbia’s official opposition, which is itself tainted by venality and easily smeared by pro-government media. Their aim is not simply to swap one patronage network for another. It is to transform the entire political culture. As one protest sign put it: “This is not a revolution but an exorcism.”57

Riot, strike, boycott

A massive economic boycott has been launched in Turkey as part of the protest movement. Boycott campaigns emerge again and again during moments of social contestation. There is a commonsense perspective — call it the spontaneous ideology of anti-autocratic movements, if you like — that boycotts are particularly effective because of the economic pressure that they are able to cause. The boycott campaign in Turkey offers an opportunity to test this hypothesis.

Struggles often pass through a sequence of “rhythmic markers” that serve as pivots or turning points catalyzing new energies.58 Often this occurs when a new social group enters the stage, or when a new leading tactic emerges. As movements unfold, they reach impasses. This happens when a tactic exhausts its disruptive potential. Disruptive tactics then need to spread to new layers of society or new tactics to emerge. For this to happen, experiments need to take place.

During the Student Intifada, for example, encampments were followed by building occupations. But mass struggles that have become revolutionary often pass through a number of tactical pivots. The 2019 uprising in Sudan passed through at least four: rioting, mass nonviolence, occupation of public space, and a general strike.59

The boycott campaign could be seen as the Second Act of the movement in Turkey. Its aim is to put economic pressure behind the mass demonstrations against the government. Yet, consistent with existing patterns within the protests, there are actually several overlapping boycotts having their origins in different layers of the movement. As a professor in Istanbul explains: “There seems to be a double process: one organised by the CHP opposition party and the other more spontaneous, led by civil society.”60

Student protesters launched a call for a total “buy nothing” consumer boycott. This runs parallel to a more targeted campaign launched by the opposition party directed at businesses associated with the government and ruling party. A website that was launched to coordinate the boycott lists the names and logos of twenty companies. Among these are a popular coffee chain, an online bookstore, a tour company owned by the tourism minister, and a number of television states and pro-government media outlets.

The call for a boycott was first announced by CHP leader Özel on March 23 as he addressed a crowd of hundreds of thousands outside Istanbul’s City Hall. This was followed by a post on social media İmamoğlu made from prison. “The idea then snowballed,” the Financial Times notes.61 Soon, spontaneous initiatives, such as a concert boycott began to emerge that originated neither from the student movement nor the opposition party.

The boycott has been described by Turkey’s trade minister as “economic sabotage.” The interior minister called it “an assassination attempt on our national economy.” It might seem surprising that it has struck such a nerve. But as the Financial Times notes: “with Turkey’s economy halfway through a tough three-year stabilisation programme and inflation still running at thirty-nine percent in February, the government’s response shows it is taking the boycott seriously.”62

The view on the ground appears less spectacular. On the first “buy nothing” day, the results were ambiguous at best. A journalist in Istanbul reported: “On a drizzly Wednesday morning, the first day that financial markets and most shops reopened after the Eid holidays, there were limited signs in the middle-class Istanbul neighborhood of Üsküdar that either the opposition or student boycotts had much effect.” The boycott, according to one account, “quickly fizzled out.”63

Boycotts are not always ineffective. There is a reason that calls for boycotts often emerge during movements. Disruptive activity is key to having the power and leverage to put forward demands. This is a shared intuition of nearly all movements today and often the point of departure for the discussion of tactics within them. Calls for boycotts resonate because they tap into this shared intuition. But often the result is only a spectacular representation of disruptive activity.

Within the present sequence of struggles, the turn towards boycotts might be thought of as comparable to strikes. The general strike in Sudan in June 2019 confirmed that the revolution had widespread support. But this alone was not enough to dislodge the military council that had come to power after the fall of the Omar al-Bashir regime. Elsewhere, such as in Kazakhstan, strike waves have provided a means to keep the embers of unrest burning after street protests died down.64 This is one way that the mood produced by an uprising circulates through different geographies and layers of society.

The consumer boycott in Turkey is similar. It offers a means of gauging mass support for the protest movement among the wider population, and of involving more people in an activity with lower risk than demonstrations, many of which lead to confrontations with the police. At the same time, it offers a means to keep the movement going during a lull in street protests.

Nevertheless, there are key differences. Strike waves during an uprising can, at times, exert real leverage on the regime. This is what happened during the strikes in the Mahalla textile factories during the Egyptian Revolution.65 (As Théorie Communiste has argued, penetrating the “glass floor” that leads into the hidden abode of production might be a necessary step in this sequence of struggles. In a word: the leap from riots to strikes.66)

Consumer boycotts, in our century, have not been able to discover the leverage necessary to create a decisive turn in the course of events. Historically, the most effective boycotts tend to resemble mass strikes or uprisings. In his memoirs, Charles Denby recounts:

A lot of tension was building up, and nobody knew where or when it would break. And on December 5, 1955, there wasn’t a soul who thought that when a working woman, a seamstress named Rosa Parks, refused to give up her seat to a white man on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, that the break had come. Each concrete act took everyone by complete surprise, from the refusal by Mrs. Parks to give up her seat to a white man, to the response to her arrest and court appearance, to the mass demonstrations led by the then unknown Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Black community running their own transportation system. It became Revolution, a word none of us ever used referring to an action defying the segregated conditions of life in the South. That mass action of revolt was the Montgomery Bus Boycott…67

A few months after the Montgomery boycott, C.L.R. James was visited in London by Dr. Martin Luther King. The following day, James wrote a letter to his comrades in Detroit describing the boycott as “one of the most astonishing events in the history of human struggle.” James described the boycott, in another letter, as “a technique of revolutionary struggle characteristic of our age,” noting “the tremendous boldness, the strategic grasp and the tactical inventiveness, all of these fundamentally revolutionary, with which they handled it.”68

In their 1958 manifesto Facing Reality, C.L.R. James, Grace Lee Boggs, and Cornelius Castoriadis described the Montgomery Bus Boycott, as one of the pivotal events heralding a new era of revolutions, alongside the Hungarian Revolution and the liberation of Ghana.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott gained national attention by disrupting everyday life in the city. As this disruption spread, it called everyday life into question. In order to sustain this disruption, the community had to examine their own lives and begin to reorganize them differently.

This was a matter of organization, leadership, and preparation. But, more than that, it is a matter of composition. The success of this tactic reflects a particular composition. Its near unanimous participation was possible due to the conditions of Black life in a segregated city in the American south. Such conditions might not be replicable.

Here is the challenge: if the aim of the boycott campaign is to add new pressure and help sustain the movement through a lull in street protests, then its success would only be possible if new tactics, energy, and determination emerge in the streets. Whether and how this will happen remains unclear.

Beginning again at the beginning

The wave that stretched from Tahrir to Taksim was described at the time by one notable French philosopher as nothing less than the “rebirth of history.” For Alain Badiou, the occupation of the squares held a special significance.

On the one hand, Badiou claimed that “what is happening has all the features of what one should call movement communism – and in a very pure form, perhaps the purest since the Paris Commune.” The experiments with forms of living not mediated by money or divided by the resigning separations of our society, the efforts to nourish and care for one another outside of the cash nexus and without reference to pre-existing identities: this was the “movement communism” of the occupations. On the other hand, pushing “beyond a certain threshold of determination, obstinacy and courage” in taking the square created an event in which “all of a sudden, hundreds of thousands of rebels can represent a nation of eighty million.”69 The act of taking the square heralded the creation of a new people. The people of the country were represented by who was in the square. This, however miraculous it sounds, does capture something about how these movements were experienced.

We might call this a synecdoche theory of revolution.70 In a synecdoche, a part stands in for the whole. Here, the square stands in for the country. The people assembled there represent the people of the entire country. Their activity in the square represents the revolution.

People from all walks of life participated in these uprisings. In each country, it began to look as if the entire country, in all of its specificity, was present in the square. This became a source of the movement’s strength. But also posed a real set of challenges.

This thread ran through nearly all of the coverage of the Gezi Park protests. An article in the Atlantic, for example, describes how protests that were initially “smallish and contained” were met with “extraordinary violence by police” after which “it quickly spiraled into a wider movement”:

After violence broke out Friday, outrage brought out Istanbulians from all ages and all sides of the political spectrum onto the streets. On Taksim Sunday, all of Turkey was represented: the young and the old, the secular and the religious, the soccer hooligans and the blind, anarchists, communists, nationalists, Kurds, gays, feminists, and students.71

Der Spiegel painted a similar picture:

Demonstrations… are drawing more than students and intellectuals. Families with children, women in headscarves, men in suits, hipsters in sneakers, pharmacists, tea-house proprietors — all are taking to the streets to register their displeasure…Kemalists and communists have demonstrated side-by-side with liberals and secularists.72

A journalist interviewed by The Guardian stressed that “that one of the main achievements of the protest movement was to shatter the narrow identities imposed by state discourse”:

Gezi brought down the walls between conservative Muslims and secularists, nationalist Turks and Kurds, Alevis and Sunnis, men and women. Everybody started talking.73

But as the euphoria of the moment passes and the dust settles, we have to return to these moments and face with sober senses their actual conditions. It was possible at the time to view the movement of the squares as a new model for revolution in our century. This intuition was not entirely wrong. The successful uprisings that have happened in the decade since have often adhered to this model.74 However, with the benefit of hindsight, it becomes clearer what some of the prominent narratives at the time, whether those of journalists or communist philosophers, seem to have missed.

First, there is the problem of leverage. Tahrir and Taksim were at the center of gravity of those uprisings, exerting a centripetal pull on everything else. But synecdochal narratives tend to miss the real stakes of the activity happening outside of the squares. During the revolution in Egypt, this included the unrest in Suez and Alexandria and the strikes in Malhalla. It was, arguably, the strike wave which coincided with the occupations and riots that gave the uprising enough leverage to topple Mubarak.75

Then there is the “composition problem.” This rears its face in two ways. The reigning separations of society tend to reemerge inside of protest movements. This experience was particularly painful for the movements of 2011-2013, as these movements had imagined themselves as already outside of the determinations of the surrounding society. And the very form of the movements, the occupation of the squares, meant different class factions having to try to find a way to live together in close quarters.76

Turkey was confronted with the division between town and country. (This is the other face of the “composition problem.”) While Istanbul burned, it seemed that the entire country was in Gezi Park or the thousands of similar demonstrations that swept across the country. The government seemed to have lost all legitimacy.77 But it was not that simple.

The whole country was not in the square. A majority stayed home. Much of the country, perhaps a “silent majority,” continued to support Erdogan and his party’s vision for the future of the country.78 In June 2013, as teargas and smoke still hung in the air, hundreds of thousands marched in support of the government. Erdogan then won the next election.

This sequence recalls the aftermath of the May 1968 events in Paris. Hundreds of thousands marched in June demonstrations supporting President de Gaulle, who then won the following election. The key difference is that the May unrest triggered a wildcat general strike which led to a massive reform package.

As mentioned earlier, the Gezi Park days were confronted by another separation. Erdogan had initiated peace talks with the PKK in 2011. The Kurdish parties were hesitant to join anti-government demonstrations at a time when that might jeopardize the peace process. But the Kurdish question was still present as a dividing line within the demonstrations.

Insurgents and the state both tend to learn from the success and failure of unrest. Tahrir and Taksim are shut down today at the first signs of unrest. For years, even Zuccotti Park in Manhattan was closed any time protests happened nearby. Governments never want to run the risk of facing a similar wave of unrest. For similar reasons, attempts are made to retake Tahrir Square and Gezi Park any time the opportunity presents itself.

But lightning rarely strikes twice. New movements often coincide with the emergence of new tactics that seem capable of navigating around old impasses. In the decade since Gezi, Occupy-style encampments have played a central role in the fall of several governments.79 But these often happen in countries that did not experience the initial wave of the movement of squares. For countries that did, the next uprisings tended to place the emphasis on more mobile and diffuse tactics.80

On May 1, thousands of protesters made an effort to storm Taksim Square. This is significant. The question today is whether it is possible to reopen the vortex that closed with Gezi Park and the defeats of 2013. Revolution, as Walter Benjamin reminds us, is a matter of redemption of the dead and of past defeats.

As Marx once wrote to Ruge: “your theme is still not exhausted, I want to add the finale, and when everything is at an end, give me your hand, so that we may begin again from the beginning.”81 But beginning again is not starting over.

The world has changed over the last decade. The unrest in Turkey is taking place under new conditions. At the time of Gezi Park, Erdogan was mostly associated with his accomplishments — a booming economy and securing civilian control over the military — which had positioned Turkey as a rising global power. But now the government in Turkey is more associated with corruption, democratic backsliding, economic chaos, and rising inflation.

The present movement cannot recreate Gezi Park. Although it might need to capture some of Gezi’s intensity. As a journalist wrote at the time:

Walking among the police stations set ablaze and the burned-out shells of buses and cars in the heart of Istanbul Sunday morning, one could only gasp and wonder, "Are we in Turkey?" Locals said they didn't recognize their city….82

But more than this, it will need to try to find a way beyond the limits that the last uprising encountered. There are promising signs. Protests have spread beyond Istanbul and into AKP strongholds. (The protests there have tended to place more of an emphasis on class demands.) Some members of Kurdish parties have begun to join the large weekly demonstrations. The invisible barriers that separate society, and prevent the spread of mass protests, have not yet collapsed. But fissures within them are beginning to appear.

In order for the uprising to succeed, it might need to have found some adequate form of leverage and a means of overcoming or suspending the divisions within the movement that have already begun to reemerge.

Credit in the straight world

The rising inflation in Turkey is related to economic policies that the Financial Times has characterized as “unorthodox.”83 In an effort to maintain relatively high growth rates, Turkey has refused to raise interest rates. In doing so, Turkey has gone against the grain of the policies of most central banks in the capitalist world. This has led to spiraling inflation. Inflation reached almost forty percent in February, the month before the uprising began.

Rising inflation has led to an increase in inequality. Inflation and inequality are often, but not always, related. There was considerable inflation in America during the pandemic and the years that followed. But real wages in the United States were rising at a faster rate than inflation. This pattern only held for so long. Anxiety about inflation and the perception that it had grown out of control contributed to the incumbent Democratic Party losing the 2024 elections.

The winds of turbulence have swept over the globe. The resulting chaos has been combined and uneven. Inflation has grown much faster in some countries than in others. This has, in part, been a result of the regional wars and the uneven distribution of their effects. But where inflation and the rising cost of living has led to unrest, protesters have tended to blame their own country’s rulers for their economic woes. This is understandable. Often in these situations, rampant inflation and the rising cost of living have been exacerbated by policies that, at the very least, could be characterized as “unorthodox.” Sri Lanka is an example of this.

Following the pandemic, economic and geopolitical instability have created a global situation that is volatile but uneven. The same conditions which make protests more likely to break out in some countries also make that unrest less likely to spread. For now this has meant a combined and uneven accumulation of chaos. But it is unclear how long this volatile equilibrium can last.

The center cannot hold. Globalization is unraveling. The breaking down of the neoliberal order finds its reflection in the emergence of various populisms. But these also act as an accelerant.

The authoritarian strongmen and populist parties rising to power in more and more countries are increasingly willing to experiment with economic unorthodoxies. Erdogan’s refusal to raise interest rates is an example of this, as is Brexit. But Trump’s second term will almost certainly accelerate this process, both locally and worldwide.

After the late 2007 financial meltdown, it required an immense, globally coordinated response to bail out the sinking ship of the global capitalist economy. The end of a shared neoliberal common sense, the unraveling of globalization, and the rise of various populisms, all within an increasingly multi-polar world, might mean that a similar scale of coordination will not be possible the next time that global markets experience an immense shock.

This could mean that the next shock to the system will be followed by a longer, deeper economic downturn. It may become harder to simply keep the ship above water. Conditions in which unrest might break out and then generalize could become much more widespread. This is what might finally break the holding pattern that struggles have been stuck for the last decade.84

After the arrest of the mayor of Istanbul on March 19, the markets in Turkey were thrown into chaos. There were worries of a run on the banks. The value of Turkish currency began to plunge. Foreign investors pulled out an estimated sixteen billion dollars in a matter of days. The central bank nearly emptied its coffers in an attempt to stabilize the market. This intervention has, so far, managed to stabilize the situation, although it is clearly still rather precarious.

Not long ago, governments spanning the globe and across the political spectrum appeared to be simply the technocratic managers of the economy. Management had superseded politics. In those circumstances, the events in Turkey would have been shocking. It would have been simply inconceivable that any government, let alone the government of a country in NATO with an economy that was among the twenty largest in the world, would run the risk of economic chaos for the sake of a political wager.

But clearly the winds have changed direction. Politics are back in the driver’s seat. Ideas, however incoherent, can become a real material force, as the new populists attempt to test the limits of the absolute domination of capital.

II. Gates of the West

Wave

Gezi Park was one of the final climaxes in a global wave of struggles. From late 2010 through the end of 2013, mass protests seemed to be taking place in every corner of the globe. But by the time that the wave had washed over Turkey, the global tide had already begun to turn. The escalating civil war in Syria and the military coup in Egypt were two of the key turning points.

A second global wave washed across the surface of the Earth from late 2018 through 2020. The Protester was named “Person of the Year” in 2019 by Time magazine. Some countries, such France, Iran, and the United States, had experienced a steady rhythm, perhaps a rising tide, of protests movements, growing larger and more intense, in years between these two moments. In certain regions, unrest leaped from country to country, with each new uprising learning from and building off of the experience of the previous one.

But elsewhere, despair after the defeat of 2010-2013 set in. This despair hung in the air over the country as if it were a dark cloud. In Brazil, Russia, Turkey, and elsewhere, the rise of authoritarian populism, the effectiveness of repression, and the confusion that was left in its wake contributed to a prevailing sense that nothing was possible. No new protests of any scale would emerge, even during the Year of the Protester. Much of the Gezi Park generation instead simply left the country. But after a long winter, the thaw seems to have begun.

Rising tide