The Impasses of Western Critical Thought

Maurizio Lazzarato

The following text was written at the end of the “cycle” of three recent books on war (War or Revolution, 2023; War and Money, 2023; and Global Civil War?, 2024). In it, Italian philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato attempts to clarify a series of concepts — imperialism, monopoly, and war — that were treated all too quickly in those three volumes due to the pressures of current events. The present essay may be read fruitfully alongside the positions developed more recently in “Why War?” and “Political Conditions for a New World Order.”

Other languages: Français

People all over the world are now discussing whether or not a Third World War will break out. On this question, too, we must be mentally prepared and do some analysis. We stand firmly for peace and against war. But if the imperialists insist on unleashing another war, we should not be afraid of it. Our attitude on this question is the same as our attitude towards any disturbance: first, we are against it; second, we are not afraid of it. The First World War was followed by the birth of the Soviet Union with a population of 200 million. The Second World War was followed by the emergence of the socialist camp with a combined population of 900 million. If the imperialists insist on launching a Third World War, it is certain that several hundred million more will turn to socialism, and then there will not be much room left on earth for the imperialists; it is also likely that the whole structure of imperialism will completely collapse. —Mao Zedong1

We can judge how tactless Rabocheye Dyelo2 is when, with an air of triumph, it quotes Marx’s statement: “Every step of real movement is more important than a dozen programs.” To repeat these words in a period of theoretical disorder is like wishing mourners at a funeral many happy returns of the day. —Lenin3

Mao’s declaration seems to have been written for our time. But mentally, we are in no way prepared for the reality of war, let alone for an analytic consideration of its causes, its reasons, and the possibilities it might open up. We lack the concepts and affects to do so. Western critical thought (Foucault, Hardt-Negri, Agamben, Esposito, Rancière, Deleuze-Guattari, Badiou, to cite only the most significant) has disarmed us, leaving us defenseless in the face of class confrontation and international war, realities that it could not anticipate because it did not construct the concepts and affects requisite for analyzing them, let alone intervening in them. The “theoretical disorder” produced over the course of the last fifty years is considerable. Without overestimating theory, we can nonetheless say that without it, there can be no revolutionary movement.

It is very difficult to develop, in one single article, a comprehensive critique of the failure of a project that sought to go beyond the limits of Marxism. We will limit ourselves to analyzing the profound damage caused by the absence of three key words: imperialism, monopoly, and war –— the elimination of which prevents us from understanding what has become of capital, the State, their relation to each other, and political action.4

Imperialism

The concept of imperialism has been practically evacuated from all of these theories in a more or less explicit manner. Hardt and Negri, at the turn of the millennium, clearly committed themselves to providing a theoretical consistency to this elimination, writing: “Imperialism is over. No nation will be world leader in the way modern European nations were. The United States does not, and indeed no nation-state can today, form the center of an imperialist project.”5

Empire positions itself as an alternative to modern sovereignty by inscribing a new world order that explodes the center-periphery relation on the basis of which capitalism was born and developed. If there is no longer any center, then there is no longer any periphery either. “The divisions of the three Worlds (First, Second, and Third) have been scrambled.”6

In the new supranational sovereignty, “conflict or competition among several imperialist powers has in important respects been replaced by the idea of a single power that overdetermines them all, structures them in a unitary way, and treats them under one common notion of right that is decidedly postcolonial and post-imperialist.”7 The “definitive decline of the sovereign nation-state”8 put an end to “the era of major conflicts…the history of imperialist, inter-imperialist, and anti-imperialist wars is over.”9 A global and supra-state governance brings “peace” with it, in the sense that wars are reduced to mere police procedures. We find a similar idea in Deleuze and Guattari, for whom world war among states has produced a global machine of which states are today but one subordinate part. Here too, the result is “the absolute peace of survival.”10 For neither of these duos is peace the opposite of war. It is a terrible peace, a “security” peace imposed by the global machine, but one wherein the “global civil war” of both Schmitt and Arendt is no longer relevant.

“This imperial expansion has nothing to do with imperialism, nor with those state initiatives designed for conquest, pillage, genocide, colonization, and slavery. Against such imperialisms, empire extends and consolidates the model of network power” that will be described in its horizontal multiplicity (flat ontology, to use a term that was in vogue a few years ago) by the theory of “biopower” and “control societies.”11

The United States is neither the hegemonic world power dominating the world market, nor an old imperialist force. Instead, its task will be to steer the world toward this new system, beyond States, to integrate differences rather than excluding them — for the American constitution is already imperial, “founded on the democracy of exodus, on affirmative and non-dialectical values, and on pluralism and freedom.”12

The world market is built from a “universal monetary regime” in which every national currency “tends to lose any claim to sovereignty.” Currency “is the imperial arbiter…but has neither a determinate location nor a transcendent status,” which means that empire nullifies the power of the dollar.13

The multitude is the other face of empire, made up of the contemporary proletariat, one that has become “autonomous and independent.” “Social cooperation is no longer the result of the investment of capital but rather an autonomous power” of the multitude.14 “In reality we are masters of the world” because the multitude “produces and reproduces directly all aspects of social life.”15

For Machiavelli, the project of constructing a new society from the ground up required “weapons” and “money.” “Spinoza responds: Don’t we already possess them? Don’t the necessary weapons reside precisely within the creative and prophetic power of the multitude?”16

The critique of these concepts has already been carried out by the reality of imperialism, genocide, financial monopolies, war, and civil wars; by the impotence of new movements which, without “weapons,” “money,” and “autonomy,” are losing, one by one, all — genuinely all — of the social and political rights won over the last two centuries of struggle and revolution. The multiplicity of movements has turned out to be aphasic, incoherent, and disoriented by the outbreak of war, a possibility left unconsidered in their theories and programs.

The point of view of a Marxist from the Global South, for whom “imperialism is a permanent stage of capitalism” is perhaps more interesting than a critique of the above theories and movements.17 Starting from the age-old continuity of the “dispossession” of the periphery by the center, Samir Amin, as early as 1978, anticipates — in an astonishing way — the development of the current political situation. After 1945, the configuration of imperialism changed profoundly. A “collective imperialism” emerged comprising the United States, Europe, and Japan, one driven by a hierarchical cooperation/competition at whose center we find the United States. Collective imperialism no longer develops inter-imperialist conflicts between the states of the North, but is, by contrast, at permanent war with the South because the “development of underdevelopment,” the “lumpen-development” imposed on the countries of the South, is time and again a condition of the North’s accumulation. In global capitalism, space can never be “smooth.” It is always necessarily polarized.

The theory of collective imperialism was perfected over the course of several events, and after the fall of the Berlin wall, it announced the equally confirmed prediction that American imperialism had defined the main enemies of its unbending will to unilateral hegemony: first and foremost, Russia,18 then China and, finally, Europe. While Europe pursues no autonomous strategy, the South has been strengthened by a U.S.-led globalization and is, in turn, extending its politico-economic (China) and political-territorial (Turkey, Russia) strength in competition with collective imperialism.

The foresight of a non-Western Marxism: not only did the war with the South become a reality, but Europe and Japan were obediently turned into colonies whose economies had been brought to their knees by the American ally. The collapse of the United States was spared only by their pillaging, itself guaranteed by the public monopoly of currency, the dollar, and by the private monopolies of the investment funds that stripped those countries of their wealth and savings in order to finance the enormous deficit resulting from the “American way of life.”19

The theory of collective imperialism rests on another strategic claim — a problematic one that nonetheless merits further discussion: the main contradiction lies between a center and an ever-shrinking periphery. Imperialist hierarchy, rather than disappearing in the confusion among the First, Second, and Third World, is radically polarized at the behest of the center. This claim, too, seems to be confirmed: political-economic opposition between the G7 and BRICS, a military confrontation against the proletariat of the South, illustrated by the Palestinian genocide. The points of confrontation are all between NATO, the United States, and Israel, and whomever the center considers its enemy (Russia, the Muslim proletariat, China), at least up until the recent change in presidency.

Samir Amin believes that the term “empire” gives way to a regrettable identification between imperialism and colonialism, which leads to an error for Hardt and Negri, for whom the end of the latter would determine the end of the former. The Franco-Egyptian economist provocatively asserts that, although it does not have a single colony, Switzerland is nevertheless an imperialist country because it participates in the “development of under-development,” which is the actual definition of imperialism.20

Monopoly

Deleuze and Guattari do not just reject the concept of imperialism, they also do away with another category fundamental to Samir Amin’s work (albeit one used far and wide): monopoly. They seem to ignore the teaching of Fernand Braudel, according to whom capitalism has always been dominated by monopolies, since the time of mercantile monopoly. The process of centralization has only intensified, accelerating further since the 1970s and reaching an unexpected climax in its dimensions (financial as opposed to industrial) in those very years.

In reading Foucault, Deleuze and Guattari, Negri, etc., it seems that after 1968 the process of centralization had come to a halt, or even been reversed. Emphasis was placed on power’s horizontality, on its dispersal and local micropolitical diffusion: for Deleuze, “nineteenth-century capitalism is a capitalism of concentration” while today it is “essentially dispersive.”21 The apparatuses of the school, the hospital, the factory that once were closed are now opened up, delineating a “smooth space” that is the internal twin of the smooth space of the world market. They no longer converge towards “an owner — state or private power.”22 “Power is characterized by the immanence of its field, without transcendent unification, without global centralization.”23

It is certainly Foucault, however, who, in The Birth of Biopolitics lectures, radically expunges the processes of capitalist centralization, transcendent unification, or global centralization, “cutting off the king’s head”24, thereby producing a radical and harmful political misunderstanding.

The categories of biopower and societies of control would like to introduce a new conception of power, one capable of critiquing all forms of sovereign power, all “excesses of power.” The science of concern for biopolitical governmentality is political economy, which Foucault defines as “an atheistic discipline…without God…without totality…without a Sovereign.”25 It “begins to demonstrate not only the pointlessness but also the impossibility of a sovereign point of view,” and affirms the existence of a “non-totalizable multiplicity.”26 The sovereign is eliminated by the organization of the market which determines prices not by the intervention of any authority but exclusively through the impersonality of competition.

Whether or not Foucault had any sympathies for liberalism is not important. What is important is coming to the realization that the conception of the economy’s functioning on the basis of the market and competition as an impersonal apparatus capable of determining prices by short-circuiting any monopolistic concentration of power is consistent with his vision of power.

The theories of biopolitics and societies of control (categories completely taken over by Hardt and Negri) see only the movement of horizontal, micropolitical diffusion of the accumulation of profit and power. It fails to grasp the other dynamic — the centralizing one that controls, decides, and organizes the horizontal dispersion of relations of domination and exploitation. In point of fact, diffusion is in the service of monopoly. The two movements have always coexisted. Marx already describes this in his 18th Brumaire. But it is centralization that exercises power and control over decentralization. War is a powerful instrument of truth because it forces us to see the dynamic that critical thought has dismissed.

Samir Amin emphasizes change within continuity. Just as imperialism has a new configuration, so too has monopoly changed since 1973-1975 (as Baran and Sweezy describe). In this respect, he speaks of “generalized monopoly,” since every productive element diffused over the land and the planet are controlled and captured by monopolies. There is no room left for any kind of autonomous, independent enterprise. Consider the example of agriculture: “independent” farmers are actually dependent upon monopolies both downstream and upstream from their production. Upstream, they depend on monopolies for seed, credit, the type of production, etc.; downstream, the sale of products rests in the hands of distribution monopolies that determine prices. Contrary to the claims of biopolitics, the market does not set prices in an immanent manner. For each sector — energy, food, financial assets, etc. — prices are fixed by a small number of companies that, right after the pandemic, provoked an inflation of profits on a global scale. Prices are not a function of “supply and demand,” but of annuity speculation (see Amsterdam’s gas “market” wherein speculative derivatives are operative, which, on August 26, 2022, multiplied prices by ten when faced with minimal changes in real demand).

Samir Amin thus reconstructs a new stage in the development of the centralization of production. But since the 2008 crisis, a new monopolistic centralization developed — one unimaginable for industrial monopoly. A very small number of pension and investment funds, which gather American, European, and global savings accounts and invest them in either American debt or financial assets (also American), now hold the astronomical sum of $55 trillion, a mass whose meaning and function we will see soon.

While sovereign power exercises the right to “make die and let live,” the eradication of the sovereign opens, according to Foucault, onto a positive administration that exercises a new right, one of “making live and letting die,” a technique of “administering life” capable of making it “proliferate.” This new dimension of power leads us, in a certain sense, out of capitalism, or at least out of the effects that it produced in the 19th century. Our problem would no longer be the production of profit — a production that simultaneously creates the wealth of some and the misery of a great many others. Today, the problem is less profit than it is “too much power” exercised over bodies, an excess of domination over subjectivity. What we must defend ourselves from “are the effects of power as such. For example, the medical profession is criticized not primarily because it is a profit-making enterprise but because it exercises an uncontrolled power over people’s bodies, their health, and their life and death.”27

It is precisely in relation to medicine as a biopolitical action par excellence that we can observe the inadequacy of the French philosopher’s new categories. Recently, Luigi Mangione was accused of shooting down Brian Thompson, the CEO of United Healthcare (UHC), shifting the debate over private insurance — a war-horse against the welfare state (championed in France by a close collaborator of Foucault, François Ewald) — back to center stage. By taking charge of the forces of life, biopower would aim to “make them grow and order them, rather than… impede them, make them submit, or destroy them.”28 Instead of all this, in the United States, health insurance companies have as their one and only objective the profit that they literally generate on the backs of policyholders whose necessary care they deny. Indeed, in 2023, United Healthcare generated twenty two billion dollars in profits, which was extorted from patients, doctors, and nurses and transferred into the shareholders’ pockets. Mangione has become a national hero (people are raising money for his defense, mobilizing outside the courthouse, defending him on social media) because American citizens, if they have any money, pay dearly for an extremely poor quality service. If they don’t have any money, they simply do not receive any care. The United States is ranked 46th in terms of life expectancy, with healthcare spending twice those of Europe, the entirety of which is converted into annuities. The decisive factor, however, is the role played by the financial monopoly over retirement funds, which hold between 20% and 25% of the top ten insurance companies. The primary shareholders of United Healthcare are asset management giants Vanguard (9% stake), BlackRock (8%), and Fidelity (5.2%).

It is monopolies that determine prices, not the market, in the same way that they decide on the coverage policies for the “insured.” Deleuze’s description of the hospital as a once closed structure that opens up and consequently changes its method of care (“neighborhood clinics, outpatient clinics, and at home care”) does not grasp the financial aspect of the problem, which is the only real problem that matters to capitalist greed, and in view of which this new method of treatment is ultimately designed to reduce costs.29

While Foucault was describing his biopolitics (1978-1979) and new modes of the exercise of power on the subject, capitalism and the (Anglo-American) State had been reorganizing themselves for over a decade to put old-fashioned profit back at the center of their politics, again and again guaranteed — always and in every case — by economic monopoly, the monopoly over executive power, the monopoly over the use of military force, and certainly not by the ordo-liberal or neoliberal market.

The nullification of sovereign monopoly action, the negation of the centralization and verticality of power, have equally pernicious consequences for the concept of power because it becomes radically pacified. Foucault writes that “what defines a relationship of power is that it is a mode of action which does not act directly and immediately on others. Instead, it acts upon their actions: an action upon an action, on existing actions or on those which may arise in the present or the future”30 while “a relationship of violence acts upon a body or upon things; it forces, it bends, it breaks on the wheel, it destroys, or it closes the door on all possibilities.”31 It is extremely dangerous and irresponsible to reduce power to affect, to the “power of affecting” and “being affected” (Deleuze). In this way, physical violence is eliminated alongside the destruction of things and persons, which is nonetheless in the midst of proliferating like a mortal metastasis over the entire planet. The monopoly of physical violence finds the highest expression of “right to make die” in the ongoing genocide, which has never been shaken by the biopower of “making live.” Foucault does allow for this possibility, but not for the right reasons: “If genocide is indeed the dream of modern powers, this is not because of a recent return from the ancient right to kill; it is because power is situated and exercised at the level of life, the species, the race, and the large-scale phenomena of population.”32 The foundation of war, civil war, predation, domination and genocide, and contemporary race wars rests, today as for yesterday, on the thirst for profit and the will to power of collective imperialism. The truth of power is given in the regime of war that destroys the welfare state and its capacity to “make live,” privatizes it, and directs its spending toward weapons for the well-being of Western shareholders.

Who is sovereign? Profit and strategy

The concept of “collective imperialism” allows us to analyze the nature of the contemporary state and its relationship with capitalism (financialized monopoly). The new imperialism gives way to a differentiation among states. While some are strengthening their sovereignty, economic power, and military power, dominating “vast spaces” (the United States, Russia, China), others, like the European States, have a more than limited sovereignty, subordinate in every respect to the unelected European Commission which, in turn, takes direct orders from the center, the United States. Even though they make extensive use of the theory of unequal exchange and dependence (particularly Samir Amin’s version) without ever using the concept of collective imperialism, Deleuze and Guattari still differentiate states on the basis of the concept of the nation-state, hence the weakness of the totality of their theoretical framework. By contrast, Hardt and Negri proclaim the end of the Nation-State, while nevertheless announcing a different, major theoretical weakness — an imperial sovereignty that has never existed. What has prevailed since the fall of the Berlin Wall is the unilateral sovereignty of the United States over states of limited sovereignty.

The limitations of the conception of the State that we find in Deleuze and Guattari and Hardt and Negri (Foucault has “cut off the king’s head”) reside in their concept of capital as a cosmopolitan force that constantly tends to exceed its own limits and eschew the borders of the nation-state. Capital is “a force that knows only immanent limits,” but all it takes is war (a political decision) to sabotage a pipeline like Nord Stream 2, leaving an entire (European) economy teetering. All it takes is the collective imperialism to impose sanctions or tariffs (another political decision) for an entire population to go hungry or wither away (Iraq, Cuba, Syria, etc.). All it takes is the American government to decide that certain technologies ought not be sent to China for the immanent logic of the market to be reduced to silence. The global market reveals that capital’s limits are not immanent to its “mode of production” but are entirely political. The Chinese state seems to be able to politically control the most deterritorialized and most abstract form of capital, finance, by preventing foreign capital from entering and pillaging the country. But already in the Trente Glorieuses, the “cosmopolitan” power of finance was subject to the political power of nation-states. If it has been liberated from those constraints, this is due solely to an entirely political will that has put it back at the center of the economy — not by its own essence, and not by its intrinsic vocation to exceed any and all limits.

The “ontological” separation of the state and capital was further exacerbated by Hardt and Negri, for whom imperialism and the state hinder the development of capital — whence the necessity of empire: “the transcendence of modern sovereignty thus conflicts with the immanence of capital.”33 Both, albeit in a different manner, seem to oppose the smooth space of production and trade to the striated space of state-based sovereignties. In reality, the dynamic of capital is inconceivable without the state; the two are not opposed as transcendence is to immanence; “gentle trade” does not eliminate war; and exchange and the market cannot function without law. There is no “mode of production” with its economic laws with sovereignty then instrumentally intervening to either promote or block an autonomous accumulation. State and capital have always constituted a common machine whose coordination/competition has only deepened since the First World War.

If the economy has not “cut off the king’s head,” as Foucault believes, then we must ask: who, today, is sovereign? Let us attempt to explore the relation that is being established between state and capital by testing the theory presented in Agamben’s Homo Sacer, which attempts to combine Foucault’s biopolitics with Schmitt’s theory of the state of exception. If it is true that the sovereign is the one who decides on the state of exception, then we must problematize the definition of sovereign and state of exception which, since the First World War, no longer seem to correspond to the realities conceptualized by Schmitt and Agamben.

The state of exception can no longer be limited to the definition that Agamben provides for it: a situation wherein the sovereign suspends the juridical norm in order to reconfigure the system of law. Already in the Weimar Republic, the state of exception could only include and have as its cause capitalist development, the irruption of the masses into politics and the possibility of revolution that they introduced, class struggle and the crises of the state that stemmed from it, the imperialist battle for colonial plunder: the state of exception concerns the suspension of all norms (productive, juridical, political) as a necessary condition for the definition of a new world order, and not “emergencies” such as the pandemic. The decision must bear on an at once political, statist, economic, and military reality that clearly goes beyond the competencies and functions of the state whose death Schmitt deplored — the state beyond parties, the state separated from “society,” the state independent of the economy, the state as the arbiter of class struggle. The state is but one player in this new dimension of sovereignty. This has become increasingly clear over the last century.

The notion of the nomos of the Earth is better able to grasp the contemporary reality of the state of exception because it takes into account the global dimension and the center/periphery division that is the foundation of capitalist domination — a situation quite different from the state of emergency internal to nation-states. The triptych that Schmitt places at the origin of all order is perhaps even more precise: take, divide, produce. “Taking” (war, wars of conquest, wars of submission and the state military system that makes them possible); “dividing” (law, private property), and “producing” (economic force) are directly imbricated with one another. From a Marxist point of view, we can consider the state of exception as an ongoing moment of “primitive accumulation.”

Schmitt’s sovereign, as taken up by Agamben, “creates and guarantees the situation that the law needs for its own validity” through the state of exception.34 In fact, the situation of the state of exception in which we find ourselves was prepared long ago by American imperialism in order to found a new order in which its hegemony could be reproduced; yet this sovereign does not even remotely resemble the one that produces the biopolitical body in Agamben’s theory, and its aim is not to guarantee law but to establish a new world order.

To be clearer still: who is the sovereign that decides on the situation of war into which we are presently being plunged — a situation indispensable for the reconfiguration of a new and chimerical American century? Certainly not the Schmittian or Agambenian State! The “sovereign” is constituted by a series of power centers which, by coordinating with each other, by confronting each other, even by opposing one another, make “existential” decisions (decisions concerning life and death) for the USA: the federal State where elected officials matter just as much as deep state officials; the Federal Reserve, which controls the dollar (the most important “product” of Yankee imperialism); industrial monopolies and American financiers who manage considerable liquidities (with the war, we discover that finance, as money, has a nationality!); the Pentagon, without whose force there would be no political and monetary order; Wall Street, who holds the purse (i.e., the predation) strings; different foundations (each one more reactionary than the other); weapons, real estate, and financial lobbies, among which the Zionist lobby is indispensable for the continued destabilization of the Middle East. It is only in this shock/coordination that the “decision” can emerge, a decision that is no longer the exclusive monopoly of the State. The State lamented by Schmitt and recovered by Agamben has not existed since at least the First World War.

The sovereign — still according to Schmitt and taken back up by Agamben — not only creates and guarantees the state of exception but also “definitively decides on normality,” that is, on the moment when the situation can be considered as sufficiently normalized, a condition for the establishment of new norms, new relations of power, and a new world order. The American sovereign itself does not decide over any “normality” because its strategy is permanent destabilization, the chaos that sows seeds of division, the condition sine qua non of its reign. The normal situation has become the continuous promotion of global civil war. The Middle East is the testing site for a destabilizing Yankee normality (Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, Syria) — a normality that the war with Russia has now also established in Europe.

Who decides when the war with Russia will end? The “sovereign.” It is precisely in relation to this question that we can grasp the multiplicity that constitutes it. A bitter political contest is raging between different centers of power over choosing the best solution for responding to the different strategies pursued by different interest groups that now confront each other within the state, finance, and the Federal Reserve.

More generally, we can assert that it is not possible to conceive of a “mode of production” separate from the state. There is no capital without the state; the latter’s sovereign and military dimension is constitutive of production. Further, the new post-Schmittian sovereignty does not exist without capital: how can American capitalist accumulation, with its abyssal deficit, reproduce itself without the state’s power over the dollar, without the exercise of the monopoly of violence that backs it up? Can the state, in its own turn, survive without its financial capacity to capture value all around the world? If not, then how else could it continue to finance its armies and 800 military bases, jihadists, coup d’états (Ukraine), and the corruption of elite “compradores”?

Deleuze and Guattari define the immanent dynamic of capital as an axiomatic. I think it would be fair to consider profit and annuity as the result of a strategy in which subjective (political, economic, military, statist, social, religious, etc.) forces all take part. The current war and its relationship with the economy shows us — or whoever proves willing to see it — the reality of this strategy. The sovereign, to adopt Schmitt’s definition, is the one who decides on the strategy, a strategy of which war and the state of exception are moments.

War and civil war

The birth or development of capitalism is inseparable from war, civil war, the use of force and physical violence against things and persons. Critical thought has adopted the bad habit of separating the political from the military and the economic from war. Rancière’s philosophy and politics are exemplary in this regard, for there is no trace left of the use of force and civil war on either side of the barricade. In Rancière, too, we only ever find the “police,” never war or civil war.

For critical thought, the democracy of old is founded on the “division of the sensible” (Rancière) or “the agonism between lettered men” (Foucault, Deleuze), an exemplary domestication of civil war (Nicole Loraux) that democratic institutions must themselves continuously ward off because they are constantly threatened by its activation.

War, and not the market (Foucault), constitutes the truth of our present or, to put it differently, the truth of capitalism is indeed the global market where capital, the state, and war act in concert. Can we conceive of the power of the United States, which oversees and perturbs global relations, without the Pentagon? Without the most powerful army in the history of humanity? Their economic and political strength immediately implies war, which they have waged without interruption since 1945. Chairman Mao claimed that there was no insurmountable wall in China between the civil and the military. The passage between one and the other was always possible and could be carried out quite brutally: the rapidity with which the ruling classes, media, and the politicians of a Europe founded on peace have moved to war simply indicates that war is contemporary with politics, albeit in different ways at the center of collective imperialism and among its vassals.

Since the 20th century, war has become more than just a means of resolving conflicts between states and classes. It also has had a direct economic function, for it plays the same role that the great inventions (the steam engine, railways, automobiles) once did. Arms expenditures have become a permanent element in the stimulation and control of economic cycles (Kalecki). The United States was only able to exit the 1929 crisis thanks to the Second World War. And the exceptional growth rate and rate of profit after the war were the results of Europe’s reconstruction following the enormous destruction of two world wars.

Real demand cannot be reduced to welfare spending alone, for the politically important component is military expenditures. It is for this reason that James O’Connor, in the 1970s, spoke not of welfare but of warfare/welfare:

In sum, both welfare spending and warfare spending have a twofold nature: The function of the welfare system is not only to control the surplus population politically but also to expand demand and domestic markets. And the warfare system not only keeps foreign rivals at bay and inhibits the development of world revolution (thus keeping labor power, raw materials, and markets in the capitalist orbit), but also helps stave off domestic economic stagnation. Thus we describe the national government as the warfare-welfare state.35

The concept upon which to construct others in order to account for current events seems to be that of “warfare/welfare,” a concept that enables us to understand the simultaneity and reversibility of the civil and the military.

The army does not just have a military function but also a “civil” function. The passage from one dimension to the other does not present a problem. Since the Second World War, the Pentagon has organized “big science” and is the beating heart of technological and scientific research and development, well beyond GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, and Microsoft). All of our technologies have a military origin, digital networks in particular.

We are thus calling not just Clausewitz’s famous phrase into question (“war is the continuation of politics by other means”), but also its inversion, put forth by Foucault and Deleuze/Guattari (“politics is the continuation of war by others means”), wherein war and politics, war and economy, succeed one another chronologically.36 Politics and war are inseparable. The division of the two concepts was true in the epoch wherein the Prussian general was writing (the 19th century), but it is no longer so today.

If critical thought treats war circumstantially, never considering it as a structural condition of capitalism, it by contrast completely ignores civil war. The exception is Foucault who, for a few years, between 1971 and 1975, attempted to make it the very model for relations of power. Not only did he quickly abandon that project for the sake of the governmentality of biopower and, later, processes of subjectification, but people never really understood what civil war he was talking about.

In the book wherein he introduces the concept of civil war, 1973’s The Punitive Society, Foucault asserts that the courses that make up the book focus on French society between 1823 and 1848. Curiously, but consistent with his theory, he says not one word about the actual European civil war that broke out in 1848. He seems to be ignorant of the fact that, precisely in this period, between 1830 and 1848, everything broke down in Europe, as Schmitt, by contrast, would note, both on the political level (masses — the “proletarian lion,” as Tronti would put it — exploded into a global struggle, never to leave it again) and on the theoretical level. In Germany, following Hegel’s death in 1831, the torch of critique (Feuerbach, the Left Hegelians, Stirner, etc.) of Western foundations (capitalism, the state, Christianity, philosophy) was ignited. From it would be born Marxism, which would guide the victorious revolutions of the 20th century. Foucault not only avoids a consideration of the most important civil war of the 19th century, the Paris Commune, but also of the European civil wars that have characterized the two world wars, just as he seems to ignore the global civil wars unleashed by the Soviet revolution, which completely reconfigured the globe at the political, economic, and military levels. Of what civil war does he speak, then, between 1971 and 1975? Between whom and whom? It’s impossible to say. In the end, he abandons the concept.

The relation of inclusive exclusion exercised by Agamben’s conception of sovereign power, like the “division of the sensible” in Rancière, functions on the same principle as the one with which Foucault considers the division between reason/madness, normal/abnormal, pathological/healthy, etc. They name relations of power on which it is impossible to base a radical rupture with the present, unlike class struggle which determines a break from which two camps emerge that can designate one another as the enemy.

Deleuze and Guattari’s claim that if the micropolitical dimension does not pass into the macropolitical then it does not “exist,” in the sense that it has no effectivity, is fully realized with war and concerns their own theory, for neither macropolitics nor this passage are ever properly defined. In the macropolitical regime of capitalism, characterized by more or less overt class struggle, the “and…and” is in no way feasible.

Foucault’s suicidal teaching to the new movements, who were eager to accept it with an irresponsible disregard, already promoted, in 1978, the current political disaster that separates the two dimensions: “turn away from all projects that claim to be global or radical,” and, in contrast, prefer “even these partial transformations” which “concern our ways of being and thinking, relations to authority, relations between the sexes, the way in which we perceive insanity or illness.”37

If we eliminate this global and radical dimension (the world market) where politics, economics, and war constitute the truth of the balance of power, we arrive at the contemporary political impotence where we lose even the possibility of a micropolitics or microphysics of power. Marx, avoiding the current theoretical blindness, considers that acting (transforming subjectivity’s relation to itself) and doing (transforming the world’s balance of power) are moments of the same revolutionary practice: “The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-changing can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice.”38

Alain Badiou thinks that the limitations of the revolutions of the 20th century lie in the conditions that produced them — wars. It is war that imposes the form of politics and organization. So, out with war and civil war, which also require military action; however, he never explains through what strategies one would be able to pursue the same objectives of 20th century revolutions.

In his conception of politics, “it is not the balance of power that counts.” Badiou rejects all concepts that have best served [fait la fortune des] revolutions (strategy, tactics, offensive, defensive, mobilization, etc.). According to him, we must even question the relevance of the concept of “antagonism.” “What is a radical politics…that maintains and practices justice and equality, and which nevertheless presupposes the time of peace, and does not wait in vain for some cataclysm?”39 We will never know.

Western critical thought as a whole failed to understand the strategy of capital and the (Anglo-American) state in the 1970s and thus embarked on blind alleys. Negri claims that Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus translates 1968. But already at the end of the 1960s, a counter-revolution had broken out that easily thwarted that “strange revolution.” In 1980, the year of the book’s publication, both the proletariat and the balance of power were profoundly altered. Foucault, in 1978, theorized a “indefinitely open history” and an “apparently endless destabilization of mechanisms of power,” which is exactly the opposite of what has happened.40 Negri’s “Spinoza” declares, despite its defeat, the “ontological”41 continuation of the revolution — a continuation through which the weakest, most disorganized and disoriented proletariat in the history of capitalism is elevated to the expression of an irreversible power. In 1979, ten years after its commencement, the first phase of the counter-revolution, that of direct confrontation [choc frontal], was brought to a close by the Fed’s speculative hike in interest rates, thus sanctioning the defeat of the revolution and celebrating the political strategy of the financialization of the American economy on the basis of “massive debt,” an approach that Paul Sweezy alone has fully understood among Marxists and critical thinkers.

The contemporary situation, beyond the impasses of critical thought, once again presents itself as a possible Leninist moment. It is still war that acts as a “mighty accelerator”42 of conflicts and potential ruptures. But Mao’s confidence in the revolutionary outcome of the world wars that the imperialists insist on waging according to their strategy is incomprehensible to Western critical thought, which lacks the “lucidity,” obstinacy, determination, and class hatred of the enemy, and is therefore devoid of any strategy.

Translated by Eric Aldieri

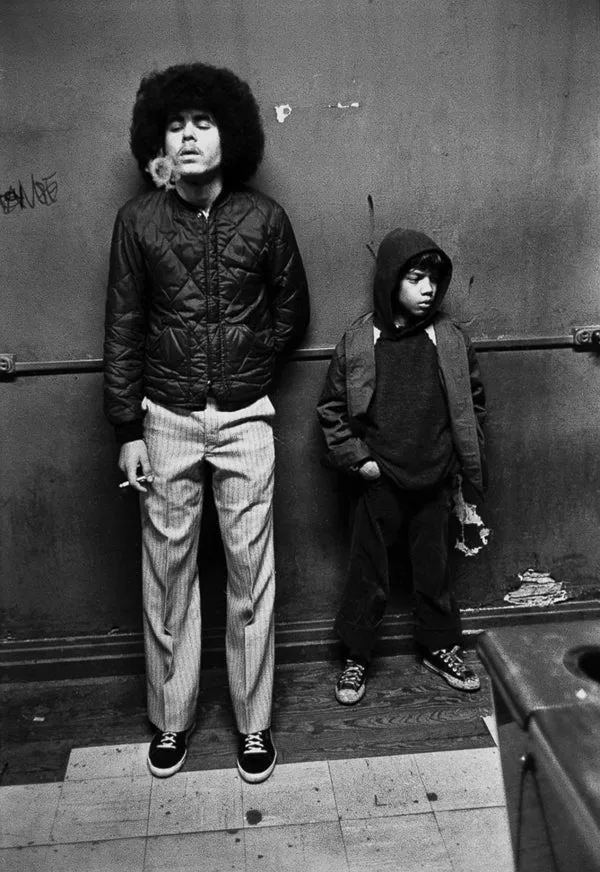

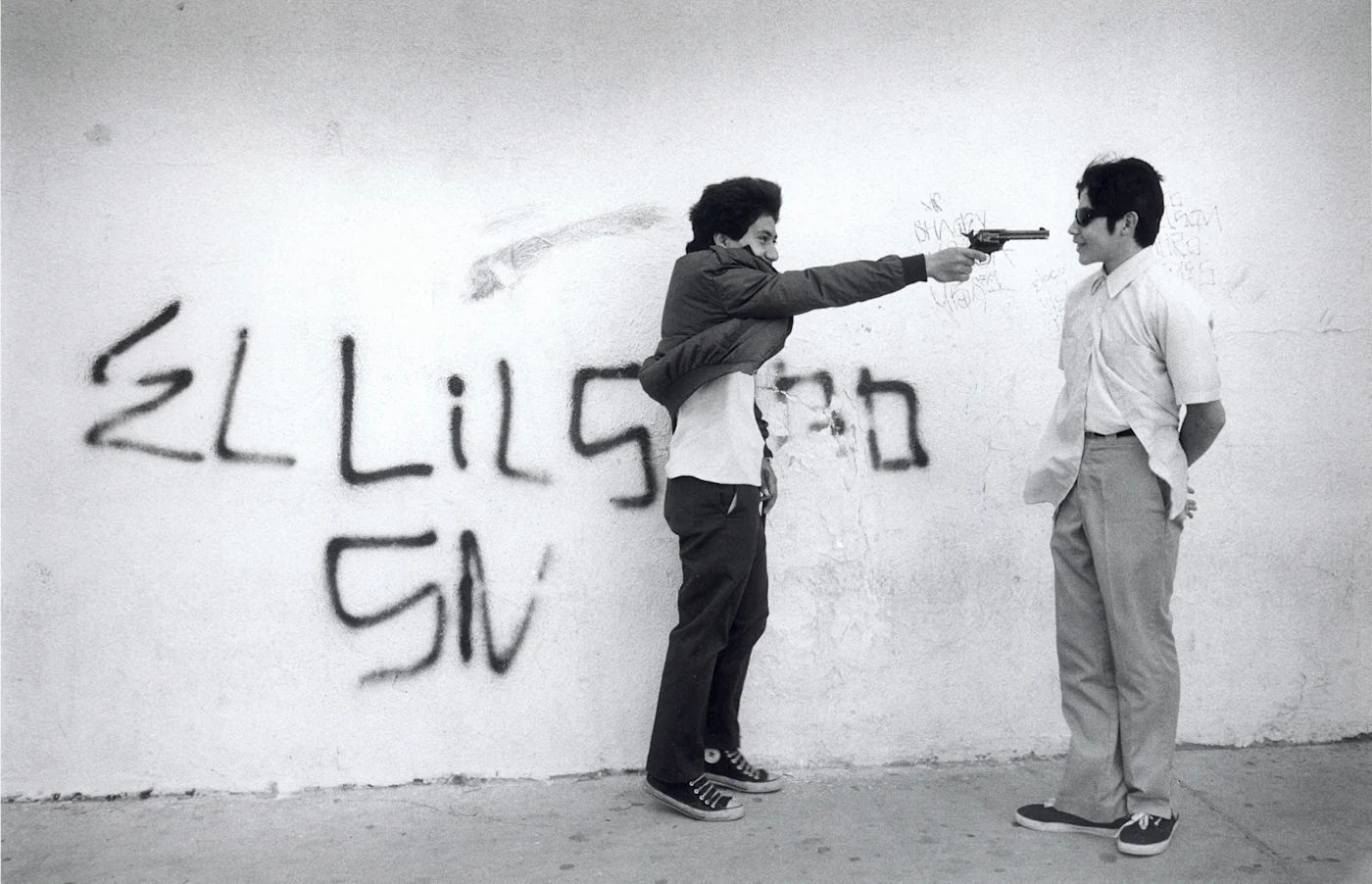

Images: Stephen Shames

Notes

1. Mao Zedong, “On the Correct Handling of Contradictions among the People.” Online here.↰

2. La Cause ouvrière, a Russian socialist newspaper (1899-1902) and fashionable voice of the social-democratic right, known by the name “economists” which joined hands with the Mensheviks in the 1903 Congress.↰

3. V.I. Lenin, What Is to Be Done?, trans. Joe Fineberg and George Hannah, Lenin Internet Archive (1999). Online here.↰

4. These three categories are absent in every postmodern definition of capitalism (cognitive, semiotic, biopolitical, neural, platform, reproductive, etc.), definitions which are based in Eurocentric points of view. They are thus not of much use for understanding what is happening.↰

5. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire, Harvard University Press, 2000, xii-xiv.↰

6. Hardt and Negri, Empire, xiii.↰

7. Hardt and Negri, Empire, 9.↰

8. Hardt and Negri, Empire, 13.↰

9. Hardt and Negri, Empire, 189.↰

10. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi, University of Minnesota Press, 1987, 467.↰

11. Hardt and Negri, Empire, 166-7. [Translation modified].↰

12. Hardt and Negri, Empire, 380.↰

13. Hardt and Negri, Empire, 346.↰

14. Hardt and Negri, Empire, 366. [Translation modified].↰

15. Hardt and Negri, Empire, 258.↰

16. Hardt and Negri, Empire, 65.↰

17. See Samir Amin, “Capitalism, Imperialism, Globalization” in The Political Economy of Imperialism, ed. R.M. Chilcote, Springer, 1999, 157-168.↰

18. Since the Clinton presidency (the 1990s), the expansion of NATO against Russia has been resolute, pursued by every president (Obama, in the interregnum preceding Trump’s inauguration, for example, put missiles in Poland), against the advice of about fifty high-ranking civil servants who had conceived and organized the containment of the Soviet Union. Thirty years ago, in a letter to Clinton, they foresaw the abandonment of NATO’s expansion because they foresaw what’s now right under our eyes — the war in Europe.↰

19. (Quoted in English in the original —trans.)↰

20. Debt, presented as an aid to the development of Southern countries, has been at the heart of the production of under-development, for it has only increased their indebtedness and forced them to sell mineral rights, infrastructure (ports, communication networks, highways, etc.) and public enterprises in order to procure the money necessary to pay back those debts.↰

21. Gilles Deleuze, “Postscript on the Societies of Control” October 59 (Winter 1992), 6.↰

22. Deleuze, “Postscript,” 6.↰

23. Gilles Deleuze, Foucault, trans. Seán Hand, University of Minnesota Press, 1988, 27 [translation modified].↰

24. Michel Foucault, Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976, trans. David Macey, Picador, 2003, 59. [Translation modified].↰

25. Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978-1979, trans. Graham Burchell, Palgrave, 2008, 282. [Translation modified].↰

26. Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics, 282.↰

27. Michel Foucault, “The Subject and Power” in Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics, ed. Hubert Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow, The University of Chicago Press, 1983, 208-226.↰

28. Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, trans. Robert Hurley, 136-137.↰

29. Deleuze, “Postscript on the Societies of Control,” 4. [Translation modified].↰

30. Foucault, “The Subject and Power,” Critical Inquiry 8, no. 4 (1982), 789.↰

31. Foucault, “The Subject and Power,” 789.↰

32. Foucault, History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, 137.↰

33. Hardt and Negri, Empire, 327.↰

34. Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen, Stanford University Press, 1998, 18.↰

35. James O’Connor, The Fiscal Crisis of the State, St. Martin’s Press, 1973, 150-151.↰

36. Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 421.↰

37. Michel Foucault, “What Is Enlightenment?” in The Foucault Reader, ed. Paul Rabinow, Pantheon Books, 1984, 46-47.↰

38. Karl Marx, “Theses on Feuerbach.” Online here.↰

39. Alain Badiou, Peut-on penser la politique?, Seuil, 1985, 106.↰

40. Michel Foucault, “The Analytic Philosophy of Politics” (delivered in Tokyo in 1978), 18. Online here. ↰

41. Hardt and Negri, Empire, 66.↰

42. V.I. Lenin, “Letters From Afar, First Letter: The First Stage of the First Revolution,” Pravda Nos. 14 and 15 (1917). Online here.↰