Life of Militancy: Japan’s Long ’68

Sabu Kohso

The sequence of revolutionary antagonism that shook Japanese society throughout the 1960s has been subject to a radical oblivion. This is true not only outside Japan, where the entire adventure remains largely unknown, but also within, as the turbulent ‘60s and ‘70s gave way to the pacified ambience of late-capitalist conformism that permeates it today. In a sweeping article — the first in a series we plan to publish on revolutionary struggle in Japan — Sabu Kohso sketches a panoramic portrait of Japan’s “long 1968,” an event that continues to configure the horizons of political struggle in the country today. Tracing its rise and decline, Kohso highlights not only the ferocity and creativity of its participants, which caught everyone by surprise, but also the objective limits into which they repeatedly crashed, the subjectivizing traps that these obstacles engendered, and the painful sectarian divisions that gradually eroded the movement from within. If it is true, as Kohso argues, that the weaknesses of Japan’s contemporary left are a direct result of its efforts to overcome the limitations of the revolutionary wave that preceded it, then the recovery of this memory is of more than merely historical value, becoming a matter of strategic urgency. If “overcoming” the long '68 came at the expense of abandoning its militant and revolutionary horizons, then the collective recovery of this memory might serve to initiate a debate over what is missing in the current configuration of forces, not only within Japan, but also at a global level.

Other languages: Español, Ελληνικά

What we call Japan’s “long ‘68” was a period of mass insurgency that passed through multiple phases between its rise and decline over the course of roughly a decade. Its origins can be found in the 1960 movement to thwart the revision of the US-Japan Security Treaty (otherwise known as Ampo), which resulted in the largest uprising in Japan’s postwar history. This impetus sparked varied forms of resistance, accelerating toward another peak in the late 1960s. The whole series of events shook the regime to its core, setting the stage for a wide range of subsequent social processes.

Looking back on this experience, however, a significant discontinuity separates the rebellious ethos of the 1960s from the pacified atmosphere that pervades Japan today. Certainly, resistance still continues: small enclaves of groupuscules and communities continue to push for a break from the status quo, and desperate oppositions still crop up sporadically in the form of riots by the socially excluded, and solitary acts of rebellion.1 On the whole, however, today’s social and political movements are primarily legalist, while anything resembling a militant mass movement is entirely absent.

The long ‘68 was the embodiment of revolutionary struggle, yet the word “revolution'' is no longer spoken, as if it had become taboo. Japanese society turns a blind eye to the radical movements of the 1960s, while populist thinkers uniformly deny the significance of these earlier rebellions. This negative reception can, at least in part, be explained as the reaction of younger generations against the authoritarian and vanguardist tendencies of the new left sects, and in particular against the dreadful internal conflict (uchigeba) that broke out among some of them. But these sectarianism traits are by no means sufficient to grasp the long ‘68 in its full scope. As we shall see below, although the intervention made by these sects was significant, it is only one part of the story. A broad range of non-sectarian and anti-authoritarian movements were also active during the years of contestation. In this respect, the experience of the long ‘68 presents us with the full range of what was possible as a revolutionary project at that historical juncture, only within the insular territory of Japan.

Since the early 1980s, a pacification of the populace that began as a reaction to the long ‘68 has also included other social transformations. These include a bubble economy that contributed to a harsher class bifurcation, neoliberal reforms that damaged social wealth and interconnectivity, and the 2011 Fukushima Nuclear Disaster, which continues to bolster national conformism even today. These forces have created a public mentality that is quick to judge any acts of autonomous empowerment that activists pursue outside and against the social order through the moralist norms of legality and pacifism. This social conformism is rooted in a pervading perception that tacitly conflates the ethical extension of power with the moral vice of violence.

In stark contrast, the long ‘68 was a concentrated attempt by various sectors of people to dismantle Japan’s postwar regime. It was a moment of collective awareness about the nature of power by which they had been ruled. Only fifteen years had passed since the end of World War II, and the people still retained vivid memories of the great violence imposed on them: the fascist regime of the Japanese Empire and its atrocities, as well as the apocalyptic destruction unleashed by American firebombings and nuclear attacks. There was also a solid recognition of the way the postwar regime had been constituted, namely, through the US/Japan military pact. After the surrender, the Japanese archipelago became a frontline base for American expansionism. The long ‘68 overlapped the escalating years of the Vietnam War, while nurturing varied movements against these dual powers. The impetus hit its limit in the early 1970s, which was the limit of a local struggle fighting against the global apparatus of war.

The pacification of the Japanese populace was accompanied by a decline in mass militancy and the loss of global perspective among the public. Yet we believe that the long ‘68 never really disappeared: it lives on somewhere in collective memory as a pool of experience that could awaken repressed desires of the people to change their society and the world that shapes it. At the right moment, this memory could function as a critical call for a new alliance of the masses and another wave of rebellion.

The following text focuses on the shift in the form of agency that Japan’s popular struggles passed through between the long ‘68 and today, namely, from revolutionaries to activists. We shall trace this change by tracking the interaction between four mutating elements: language (from commanding discourse to self-organizing enunciation), organization (from authoritarian party to horizontalist groupuscule), subjectivation (from self-negating petit bourgeoisie to self-affirming precariat), and militancy (from centralized force to autonomous empowerment). We shall consider not only how these shifts came about, but what was both gained and lost in the process. In the final instance, we are convinced of one thing only: the political ontology that grounded the leading idea of revolution (or of changing the world) during the long ‘68 has today become obsolete, while a new one is still waiting to be articulated.

The Early 1960s

The urban uprisings that erupted in countries across the world, and which are loosely associated with the year ‘68, were marked by varying temporalities, peaks and extensions. In Japan’s case, however, it is useful to see the entire decade of the 1960s as one long ‘68, i.e., as a single process with two peaks punctuated by uprisings of very different character, which began with the 1960 uprising against the renewal of Ampo and ended with the 1970 uprising against its extension.2 It was this timeframe that formed the shared horizon among participants in the late 1960’s struggles, all of whom trained their eyes upon the uprising to come in the 1970’s. As they saw it, the 1960 uprising formed both the model to follow and the limit to overcome.

Let us begin by examining the 1960 uprising, the first peak of the long ‘68.

“Ampo” was the 1951 defense pact designed to obligate Japan, in cooperation with America’s military intervention. In addition to providing its territory for use by military bases, Japan also produced various weapons parts during the wars in Korea and Vietnam. This subservience helped the nation quickly recover from the ruins of war and move toward a consumerist, mediatized society. In this way, the long ‘68 coincided with a decade of extreme social change marked by what the government referred to glowingly as “high economic growth.” Community-based socialities of yesteryear were shattered by industrialization and development: peasants who had lost their means of subsistence increasingly sought work in cities, while university students saw their status transformed from that of national elites to consumers in mass society like any other.

In much the same way, the nature of uprisings likewise changed over the course of the long ‘68. During this period, we see a shift from national mobilizations against the US hegemony and the Japanese government as its puppet in 1960 to mass uprisings against these same powers during the escalation of the Vietnam war leading up to 1968. While the 1960’s mobilization against Ampo was driven by a nationalist impetus toward independence from America, the late 1960s’ struggles aspired to global revolution against imperialism and Stalinism. In this significant transformation we see a passage from a concentrated, molar event to a reverberation among decentered, molecular events. These polarizations of struggle were born out of the interaction between an insurgent mass corporeality and revolutionary groups, reverberating and conflicting in “schismogenetic processes” since the birth of the first new left sect, i.e., the Communist League, otherwise known as Bund.3

Bund was established in 1958 by young members of the Japan Communist Party (JCP) who were active in the All-Japan Federation of Students' Self-Governing Associations (Zengakuren) who left the party after objecting to its conversion to parliamentarism in 1955, combined with the Soviet intervention following the uprising in Hungary the following year. In 1960, the National Council for Preventing the Revision of Ampo was assembled by a coalition of the JCP, the Japan Socialist Party (JSP), the General Council of Trade Unions (Sōhyō), and Zengakuren, among many other organizations. Above all, increasing numbers of the general public joined the street protest. Under the leadership of Bund, Zengakuren succeeded in spearheading the movement, overpowering the JCP; yet at the climax of the protests, the movement itself was overwhelmed by the masses, who spontaneously broke into and occupied the National Parliament Building in Tokyo. The uncontrollable energy of the insurrectionary crowds shocked the Bund members, who had trusted in their capacity to steer the herd.4

After this experience, the Tokyo Bund split into three factions, which reflected divergent assessments of the event. The rupture triggered a schismogenetic process within the new left, from which several sects and groupuscules would appear.

It was also in 1956 that another early new left organization, the Revolutionary Communist League (Kakukyōdō), was established by Trotskyist intellectuals. By contrast with the action-oriented current of Bund, Kakukyōdō was smaller and more reserved, yet determined to create a Leninist-style synthetic party organization. With the tripartite disassembly of Bund, Kakukyōdō absorbed two of the three divergent factions and became the biggest sect. However, in 1963, Kakukyōdō itself split in half, resulting in the Core Faction (Chūkaku-ha) and the Revolutionary Marxist Faction (Kakumaru-ha). This bifurcation would inaugurate the harshest phase of uchigeba in the 1970s.

When we consider Japan’s new left sects, the problematic nature of their discursive practice always stands out. As the years go by, we increasingly sense the gulf between what they said and what they did, between the grand objectives they maintained and the ephemeral situation they grappled with. Herein lies the experience that we want to grasp.

Notwithstanding their ideological diversity, the new left sects equally stood in opposition to the JCP, which maintained its hegemony over labor unions and popular social movements. This minor position led them to doggedly compete against one another in search of a unique idea and program for the revolution — a revolutionary party — a task the JCP had failed to fulfill. The schismogenesis of these sects developed in lockstep with their theoretical production toward this objective. Thus, they adopted Marxist theories of all sorts, developing them in their own ways, including phases focused on alienation, reification, technique and globality, all of them based on political and economic theorizations drawn from Das Kapital (especially those of Kōzō Uno). These theories are valuable in their own rights; however, the way the new left sects adopted them was exclusively for creating a grand teleology from which to deduce party objectives and mobilize workers and students to realize them. In this way, the desire to transform the world, society, and life that surely nurtured the will to revolt of heterogeneous antagonists was unequivocally captured by doctrinal slogans, rather than creating a collective enunciation for their empowerment using theories only as a regulative guideline.

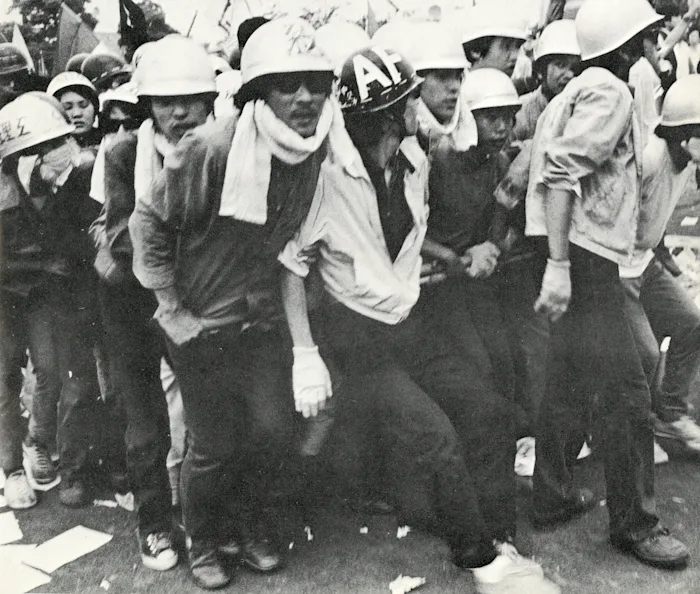

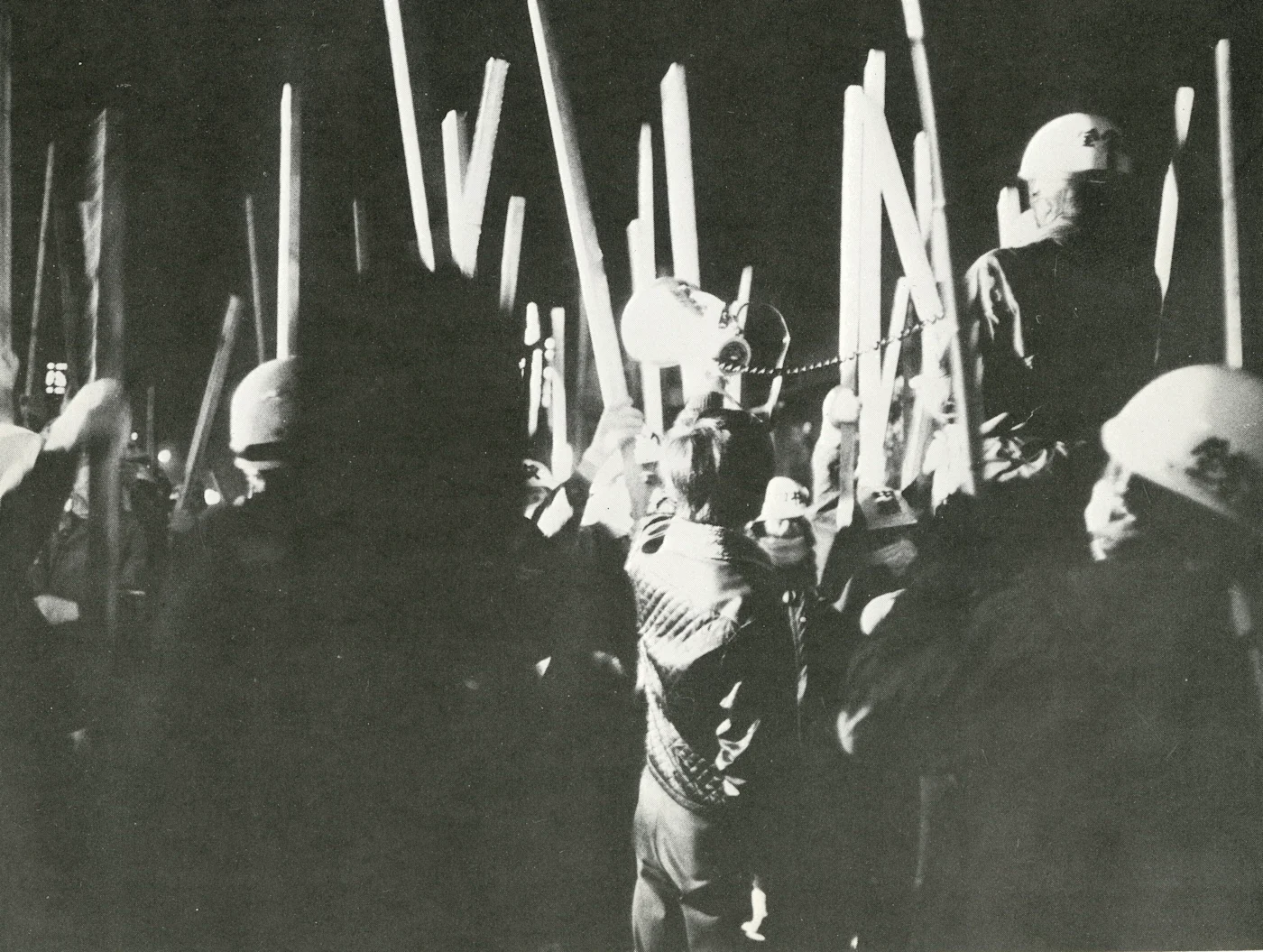

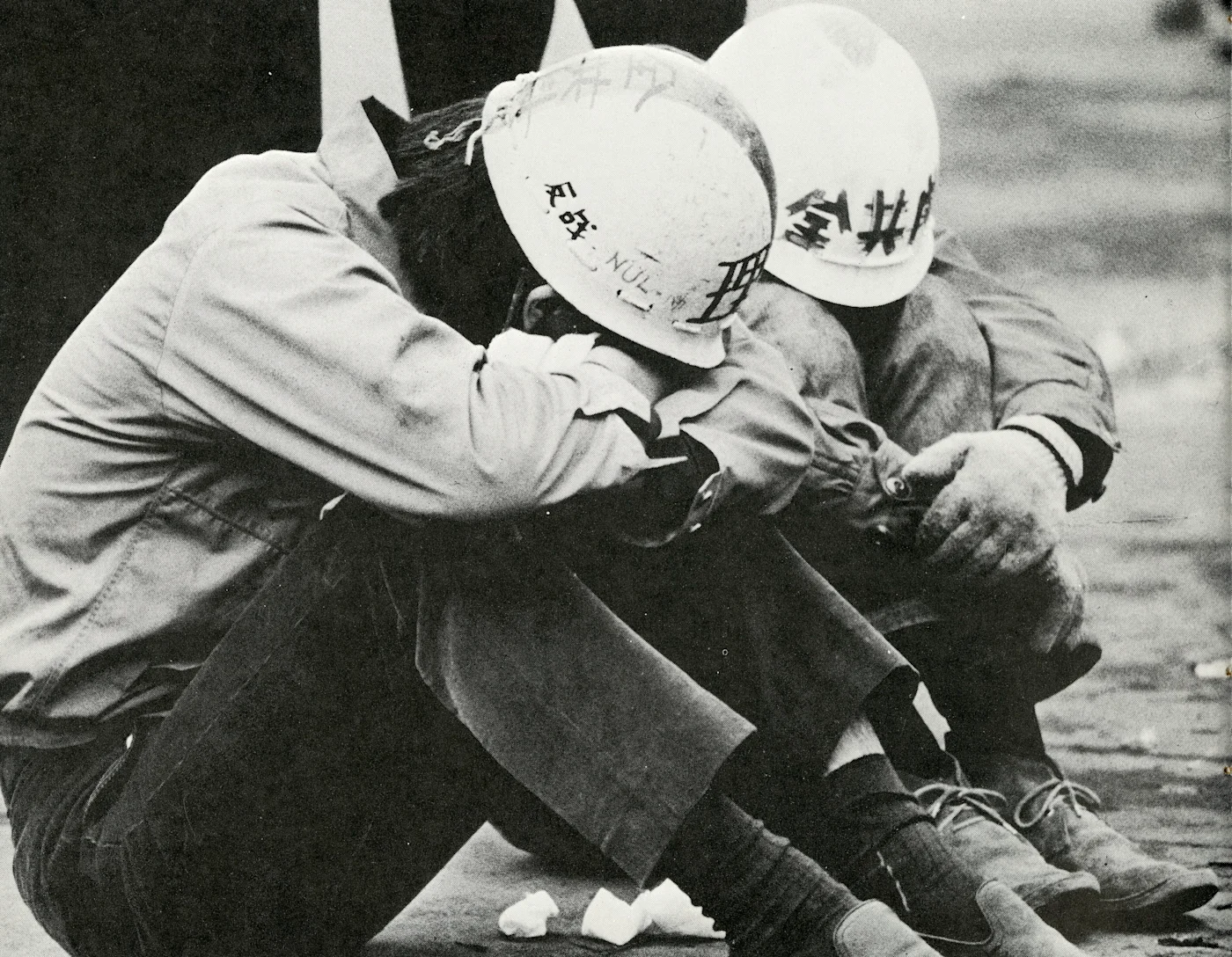

Nevertheless, the capacity of new left sects to mobilize workers and students for actions was undoubtedly remarkable. The long ‘68 was visibly the age of Marxist ideologies, which boasted the spectacle of serried ranks of fighters in color-coded helmets clashing with riot police more or less everywhere. But there was another, less visible, yet arguably more crucial impetus, namely, the non-sectarian, anti-vanguardist current. In many ways, it was the interaction between sectarians and non-sectarians that ultimately gave Japan’s long ‘68 its distinctive character. As we shall see, this interaction embodied an asymmetric relationship between two different modes of power, militarism and militancy, which nurtured a singular impetus of rebellion.

The year 1960 witnessed another momentous uprising: the labor dispute at the Miike Mine in Northern Kyushu. A massive layoff took place in the coal mining industry, which had fed the backbone of Japan’s modernization, but which was now in downturn following the shift of industrial structure from coal to oil. Although the dispute took place in an industry that was evidently in decline, the miners’ struggle successfully attracted forces from across the left to its cause, which was referred to in heady terms as the confrontation between total labor and total capital.

It was this struggle that developed the tactical repertoire that would become the model for anti-vanguardist, anti-authoritarian radicalism, as distinct from modus operandi of the new left. If the 1960 anti-Ampo movement mobilized the urban masses of Japanese civil society, the constituency of the miners’ strike was a multi-ethnic proletariat that included not only Japanese but also Okinawans and Koreans. The communities of miners thus became an exchange base for a trans-East Asiatic underclass, who lived in the shadow of Japanese prosperity. Organizations of the miners’ struggle were closely tied to their everyday lives and communities. This was an instance wherein the rise and decline of the movement set the terms for the survival or demise of the community as such.

The Miike struggle ended in a series of melees, partly caused by the hierarchical division between permanent workers and temporary workers. In an effort to overcome this defeat, a group of workers at the Taishō Mine around the poet and theorist Gan Tanigawa organized an anarchic groupuscule called the Taishō Action Troupe within the official coal miners’ union affiliated with Sōhyō.5 Employing affinity-based organizing and elusive tactics of disruption, the group escalated the dispute over wages beyond the point of compromise sought by the official unions, and ultimately created an autonomous community of unemployed workers in a coal mining mountain that was in the process of being gradually abandoned. For many revolutionaries who had felt defeated by the 1960 anti-Ampo wave, this struggle provided them with an inspiring new model of organizing that would continue into the late 1960s.

Tanigawa also co-founded Circle Village, a zine collecting the voices of miners’ communities — not only of the workers but also their families — across Northern Kyushu, along with feminist authors Kazue Morisaki and Michiko Ishimure, who would play crucial roles in struggles for women’s liberation and the anti-pollution movement in subsequent years.6 The zine was part of the broader Circle Movement project, which aimed to create common ground among heterogeneous workers across Japan by facilitating their exchanges through cultural production. In these various ways, this discursive practice contrasted starkly with that of the new left sects: rather than commanding slogans designed to induce unilateral mobilization, it produced a genuine collective enunciation for self-empowerment and autonomy.

Meanwhile, militant individuals and groups across Japan synched up with the miners’ struggle. Numerous affinity groups initiated direct actions and publication projects, including the sabotage of a Tokyo bank that served the mining industries in Kyushu (by the Tokyo Action Front) and the dissemination of information (by Revolt Co.) on minority struggles and revolutions in the Third World. Such practices created transversal connections between various movements stretching from Kyushu to Tokyo and East Asia and beyond, trespassing the national territory of Japan.

Militarism and Militancy

During the years 1967, 1968, and 1969, alongside the rise of anti-Vietnam War movements, the struggles of students, workers, farmers, artists and citizens gave birth to an unprecedented oppositional impetus against the postwar regime of Japan, which the new left sects branded as “Japanese Imperialism.” A gigantic reverberation among popular movements — including the Sanrizuka farmers’ movement against the construction of Narita Airport, the Okinawan people’s opposition to the US military bases, the wildcat strike by National Railroad workers, students in occupied universities, and an assembly of various anti-Vietnam War initiatives — contributed to a multilateral insurrectional process. Small to large riots were taking place across the metropolis.

One aspect that conspicuously distinguished the tumult of the late 1960s from that of 1960 was an intentional radicalization of power, which took two different directions. In many instances, it contributed to an uptick of militarism among new left sects, at the level of both weapons and organizational form, as these groups sought to ready themselves to confront the state and take power. On the other hand, there was an effort to empower militancy to nurture the autonomy of life, community, and struggle, which was observed among local struggles such as the miners’ communities and the farmers’ community in Sanrizuka.

The name Sanrizuka is known internationally, as it has often been associated with more recent land-based struggles outside Japan such as the ZAD at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, among others.7 The peak of the farmers’ efforts to disrupt the state’s construction of Narita Airport lasted from 1966 to 1978. By 1967, the farmers were determined to cut ties with the JCP and collaborate with new left sects instead. Their collaboration thus created a singular movement grounded in a concrete relation to the farmers’ community, which was able to develop creative tactics with a wide range of intensity. The principal agent of the struggle was always farmers, who were self-organized according to the composition of their community: affinity groups of elders, youths, mothers, children, and so forth.8 While the main troupes of the new left sects intervened during synchronized actions from outside, some new left activists abandoned the city and took up residence within the community. During the moments of critical confrontation, the farmers’ community became a camp for all kinds of radical groups and activists.

The decisive point is that we see here a militant community with the capacity to accommodate multiple, otherwise diverging or conflicting groups in such a way that they were able to fight side-by-side. These were capacities that the militarist sects themselves could never conceive.9 As we see it, militarism forges hordes of workers, students, and others (war machine) into a hierarchical organization through a disciplinary normalization of language, behavior, body, and relation, in order to confront state power as its symmetric opponent. By contrast, militancy reflects an ethical measure of power directed instead toward the enrichment and intensification of autonomy. The latter tends to confront state power asymmetrically by weaponizing the lifeworld in its full sense: corporeality, reproduction, and communality. This asymmetricity can encompass a spectrum of forms of power within it, from conflictual initiatives to more hospitable sensibilities.10

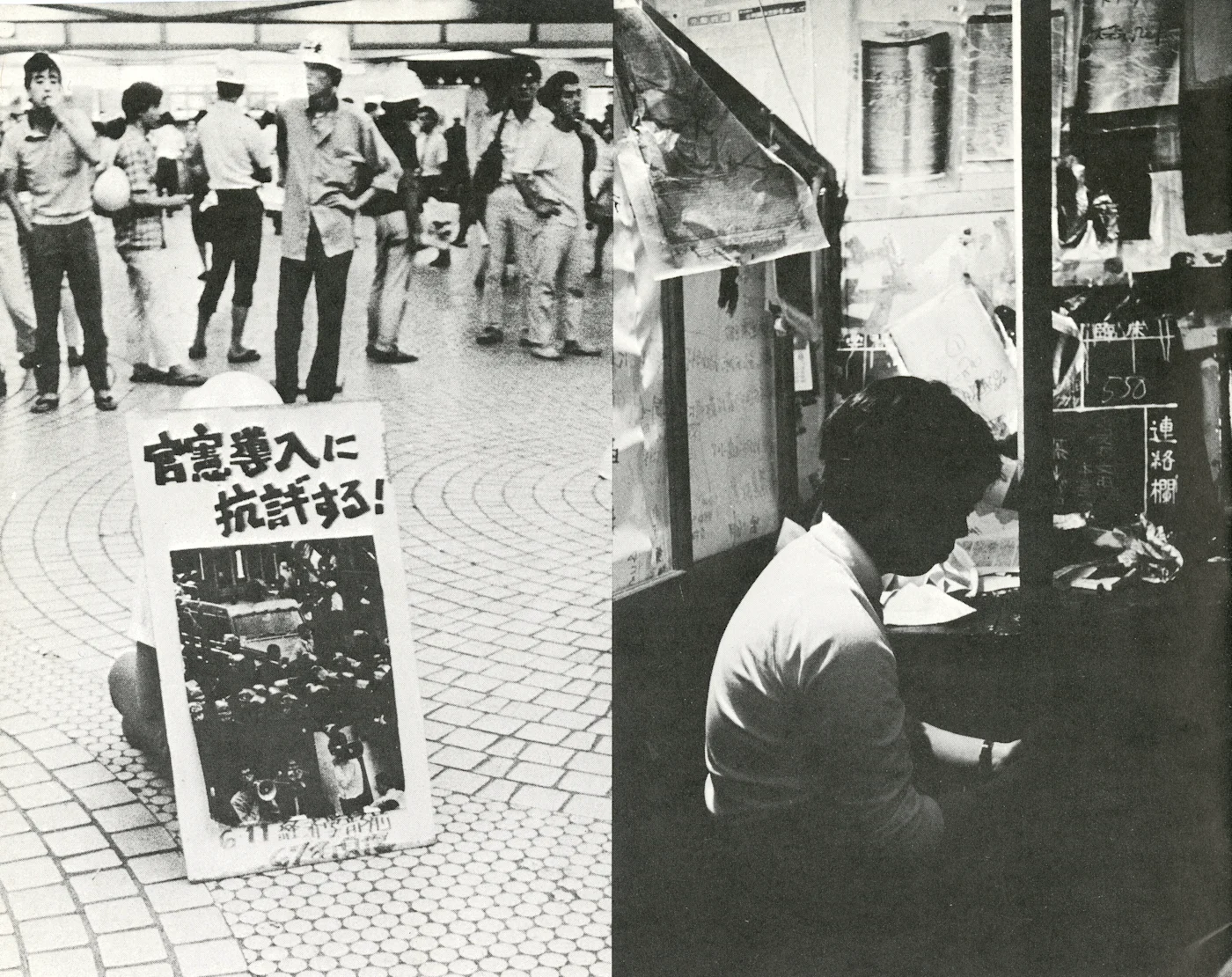

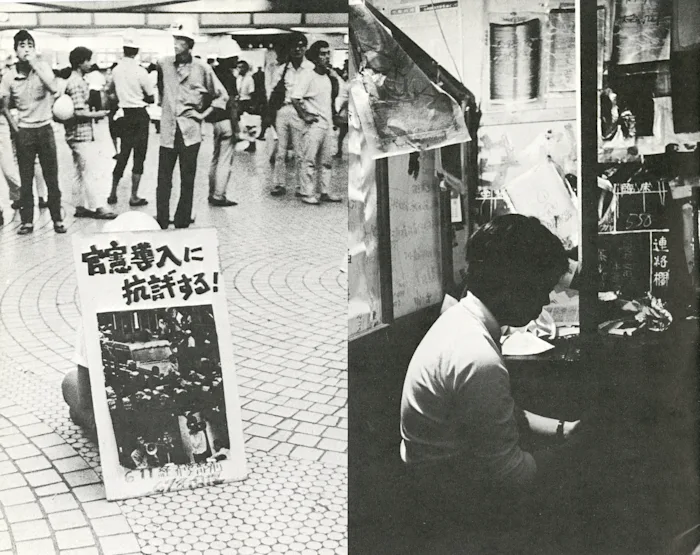

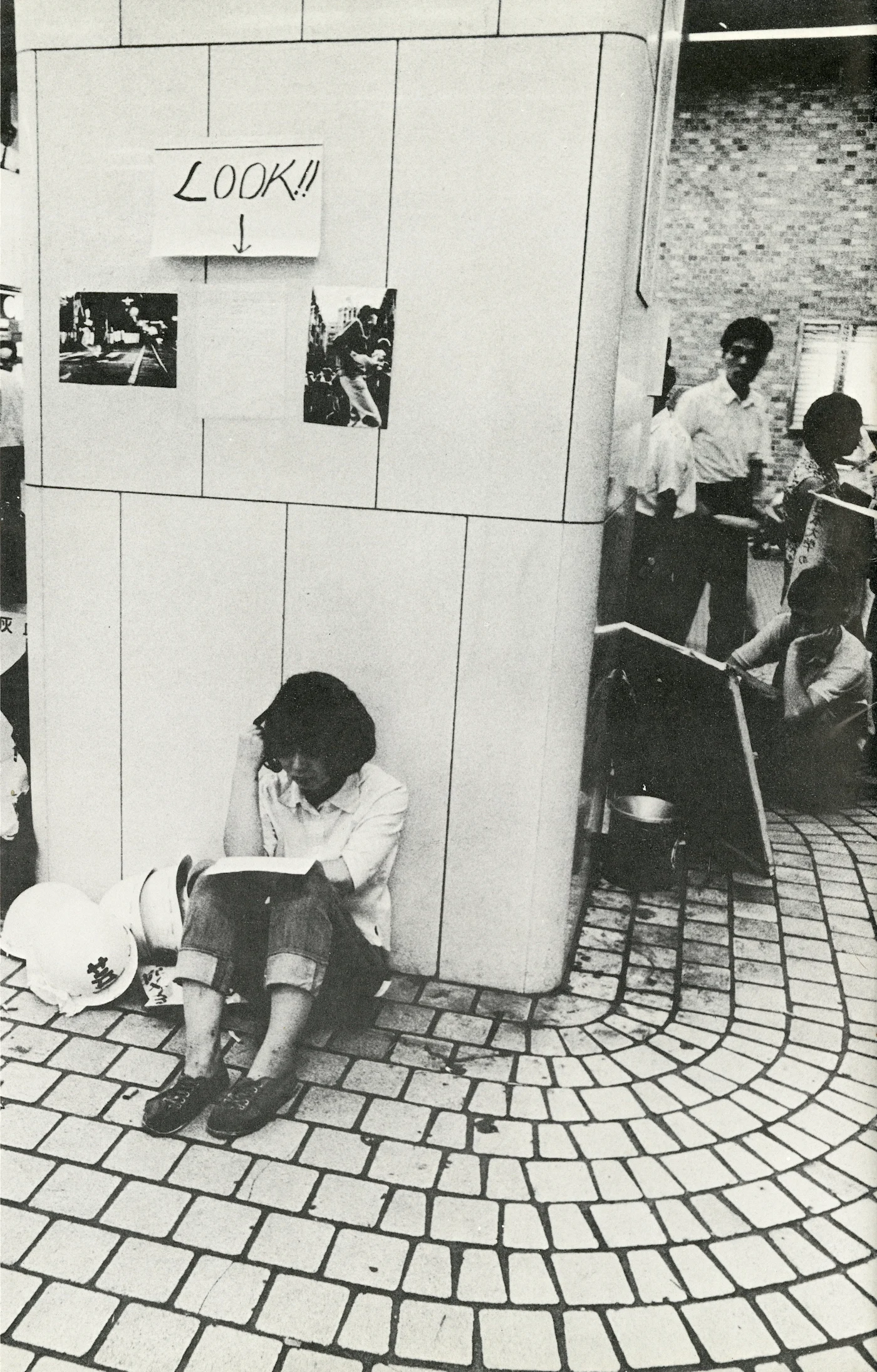

This power of militancy was observed in student organizations as well. As we have seen, the 1960’s anti-Ampo uprising was spearheaded by Zengakuren, which was a national association of representative committees with formal chapters in many universities. By providing students with space and a budget for extracurricular activities, it quickly became the main stage for a turf war among new left sects, as well as the Democratic Youth League (Minsei), the youth organization of JCP. By the mid 1960s, Zengakuren chapters in each university were subsumed under the domination of a particular new left sect, or Minsei. In response, a new association of students — the All-Campus Joint Struggle Committee (Zenkyōtō) — was created, inspired by the Taishō Action Troupe, which formed an anarchic and decentralized network for students’ autonomous organizing and action. Professing to be non-sectarian, it was independent of any new left sects, yet open to their participation.11 It opposed tuition hikes, administrative corruption, and the role of higher education in the reproduction of class hierarchy. Throughout 1968 and 1969, the Zenkyōtō movement spread spontaneously across the nation and carried out occupations and barricade strikes in many universities as well as some high schools. Occupied universities and high schools then became the bases for various street actions, as well as students’ self-organized lectures and events.

As student struggles targeted the role of the university in the reproduction of class, it nurtured a self-critique (jiko-hihan) of their intellectual/petit bourgeois status vis-à-vis the proletariat. However, this self-critique also included a vision of their own liberation, that is, with the attempt to dismantle an education system that valorizes human ability mono-dimensionally. The slogan “dismantle the university” thus synchronized with “dismantle the self.” As such, the Zenkyōtō movement incorporated a radical critique of power/knowledge in higher education, and in society writ large.

All these events of the long ‘68 developed alongside an increasing permeation of mass media — the advent of the society of spectacle. As street events and media events began to synchronize, media events started to absorb street events, to the extent that no action was effective if it was not circulated as a media spectacle. At the same time, as the gravity of cultural politics continued to grow, it led to the creation of radical artistic movements — theater, dance, cinema, music, and visual arts. In the arts, the most outstanding tendency was a return to the body and its eroticism — as if “the real” that had been lost could be revived only through the spectacle. The erotic symbolism of themes such as sex, violence, and crime permeated rebelliousness in counterculture. In the vanguardist sector of arts, the passion for violence was especially fetishized in cinematic and literary forms.12 This tendency to encourage intensifying confrontation with state power began in the late 1960s, but its negative effect would not truly be felt until the 1970s.

Uchigeba and Decentralization

For all the radical groups who coordinated to make it possible, the aim of the 1970 anti-Ampo uprising was to disrupt and dislodge the treaty, thereby overcoming the limitations of the 1960 uprising. If it fell short of expectations, this failure was attributable to the character of late 1960s insurgency more broadly, which drew its impetus from a reverberation among heterogeneous forces that never quite fused into a unified movement, as it previously had. As the momentum dwindled following the disappointing outcome, the insurgent impetus was captured by the demand for an armed uprising on the part of the militarized sects.13 During the same period, a few sects began to intensify their reciprocal uchigeba, resulting in a protracted intra-sectarian war that would last for several decades (continuing until the early 2000s), and resulting in more than a hundred deaths and thousands of heavy injuries.

The most intense conflict erupted between Chūkaku-ha and Kakumaru-ha, former comrades in Kakukyōdō. While the two shared a faith in vanguardist mass mobilization, the former emphasized militant action against the state, while the latter prioritized the consolidation, protection, and expansion of the party organization. Their conflict was the worst embodiment of Bateson’s notion of “symmetric schismogenesis” which, in contrast to “complementary schismogenesis” (which creates submission), invites limitless competition. As such, they fueled an endless contestation to be one and only Party.

Japan’s Red Army Faction appeared in 1969 through a factional split within Bund in the Kansai area. Owing to their explicit emphasis on armed uprising, they soon became the primary target of a state crackdown. In the interest of survival, they formed the United Red Army (URA) with another militarist group, the Revolutionary Left Faction of the Japan Communist Party.14 This was an odd couple between two divergent tendencies, the first internationalist and Trotskyist in leaning, the second more nationalist and Maoist. In an infamous episode, the URA ended up killing fourteen of its members during military training, in the form of disciplinary interrogation. In 1971, the group met its end in a gunfight with police.15 This event marked the beginning of the end of party politics in Japan’s revolutionary movement.

Once the university struggle led by Zenkyōtō had come to a close, following the crushing of the occupations by police forces, the student radicals who had participated in them were faced with a choice: do we give up the struggle and return to “normal life,” or do we abandon our academic careers and dedicate our lives for revolution? Among those who chose the latter, their subjectivation followed a particular process of self-dismantling and reassembling that began with self-negation (jiko-hitei) as an extension of self-critique (jiko-hihan). After deserting their universities and high schools, former students would become farmers, workers, or soldiers in various sites of popular struggle, including Sanrizuka, the day-laborers’ ghettos (yoseba) such as Sanya in Tokyo and Kamagasaki in Osaka (more on this subject later), the struggle in Okinawa over the reversion of their territory from US to Japan or else in the direction of independence, or the guerrillas fighting against American imperialism abroad. In short, it marked a decentralized diffusion of the insurgent mass corporeality of the long ‘68 into the world.

Amidst this protracted process of diffusion, several ultra-militant groups appeared who strove for a maximal intensity of engagement. Two groups in particular — the Japan Red Army (Nihon Sekigun) and the East Asia Anti-Japan Armed Front (Higashi Ajia Hannichi Busō Sensen) — challenged the limits of national revolution, as it were, by deterritorializing it. Thereby they became explicitly anti-Japan in different vectors, both from within and from without.

Although loosely associated with the Red Army Faction (mostly through personal acquaintance), Nihon Sekigun was itself a strictly independent group of internationalist revolutionaries who left Japan and joined the global guerrilla war campaign against the capitalist bloc (including Japan) led by American imperialism in collaboration with the PFLP.16

Higashi Ajia Hannichi Busō Sensen was an association of anarchist-leaning affinity groups (Wolf, Fangs of the Earth, and Scorpion) that engaged in successive bombing attacks against various targets in Japan, include large corporations implicated in Japanese imperialism and state monuments celebrating Japanese colonialism and the emperor. These attacks were carried out in the name of the Ainu people, Koreans, Chinese, as well as day-laborers in Japan. These affinity groups aimed to expose the colonialist history of the Japanese empire and while attacking its historical present from within.17 They enacted the self-negation (jiko-hitei) of being Japanese in its most extreme form. On their reading, the limit of the long ‘68 lay in the contradiction between being Japanese and being an agent of revolution, given the counter-revolutionary nature of Japan’s colonialist expansion.

The experiences of these two groups have never been subjected to full scrutiny.18 Most have opted to steer clear due to the difficulty of detaching their achievements from the tragedies involved in their actions. After the armed groups’ disappearance following the state crackdown and the imprisonment of their members, there came a long hiatus in revolutionary struggle. This would eventually spell the end of the new left’s revolutionary politics. But the militant impetus quietly survived in the struggles of resistant communities, as well as in small milieus of anti-capitalists and anti-fascists.

The Global '68

The global '68 was a singular event, yet, at the same time, we believe it was the beginning of a cycle of global uprisings. A new planetary force arose, cutting across the world order in multiple trajectories. Evidently it was an effect of one and the same densification of planetary interconnectivity of the capitalist-state’s mode of development over the earth. On the one hand, so-called globalization had been accelerating environmental degradation and intensifying the unevenness of development since the colonial era. At the same time, the concomitant permeation of trade and media networks came to allow the acceleration of civilian interactions through personal travel as well as information exchange — and this latter included interaction among the popular struggles of distant places. In the dark prospect of the future, global interconnectivity nevertheless materialized a new path toward a synchronicity of popular struggles, distinguishing itself from the international unification of socialist states.

The struggles waged by the new left sects followed internationalism in the world order, in which the idea of revolution was to liberate the oppressed (proletariat) by taking over and changing the political, social, and economic institutions of the nation-state in a socialist direction, on the assumption that a unification of socialist nation-states could create a communist world. But the historic rallying cry — “Workers of the World Unite!” — had been betrayed, during the Second International and at the outbreak of WWI in 1914, when the socialist and social democratic parties lined up to support their nations’ wars. Ever since, we have been ensnared within the same barriers of an internationalism of nation-states, the new left sects being no exception to this pattern.

The global ‘68 embodied the limit of a politics of world order — be it nationalism or internationalism. At the same time, there was an opening to a still unknown politics of the Earth. In this sense, the global ‘68 was a watershed moment, a shift from one idea of revolution to another: from “changing the world by taking power” to “changing the world without taking power,” from a synthesis of nation-states to an association of autonomous zones, from national subjectivity to the subjectivation of planetary inhabitants. This shift of political ontology is still underway, still incomplete. Either for the moment or indefinitely, we are caught in the middle, oscillating in between.

A cycle of global uprisings is an event, not a method. It cannot be planned any way we like. It happens only when the conditions for the reverberation of struggles are ripe. For some time now, we have witnessed a reverberation of uprisings from one place to another, simultaneous or in succession, on a global scale. But there have been lost instances of continuity, too. One thinks here not only of Japan but also of Korea, where one of the largest insurrections in recent history took place in 1980. Thanks to the sacrifice of many participants, the Gwangju Uprising marked the beginning of the end of dictatorial governance in Korea, the latter having been initially nurtured by Japanese imperialism, before being revived by American imperialism. Unfortunately, the uprising found no substantial reverberation in Japan.

At this time, Japan was in the initial stage of the 1980’s bubble economy. In the discussions around postmodernism that emerged in Western academia during this period, the country became the model of a non-Western contemporary capitalist society (one thinks of Alexandre Kojève’s remarks on “post-historical society”, or Roland Barthes’s on the “empire of signs” turning around a void.)19 As if acting-out these prognostic projections, Japanese society unabashedly embraced the desire to enjoy commodity culture, casting aside any collective desire for change, resulting in an atmosphere that would depart, as far as possible, from the ethical culture of the new left. Desire was reduced to the taste in food, fashion, and arts. A culture that is sheerly aestheticized — and no longer ethico-aesthetical — became the token of Japanese exceptionalism. The people seemed to be largely mobilized by the soft nationalism promulgated by consumerism and the media. It was precisely this climate that brought the long ‘68 to a close, while preventing any synchronic uprisings from rising in Japan.

Inhabitants’ Resistance

Beginning with the 1970s, Japanese society was materially transformed by massive development. Nationwide infrastructure, transportation and media networks were reconstructed and expanded through state initiatives.20 The privatization of the public sector (including the National Railways [Kokutetsu]) debilitated the political power of working populations, while university reforms deprived students of their bases of autonomous activity.

Alongside the national mobilization by consumerism and the media, however, another less visible situation was developing. During the 1980s and 1990s, a broad precarization of work put an end to the promise of lifelong employment made to the nation by the postwar regime. The average university student turned out to be a part-time informal worker who no longer needed to practice voluntary self-negation (jiko-hitei) to enter the proletariat. All in all, the nation became polarized between those who enjoy visibility and a voice (Japanese citizens) and those who don’t (day-laborers, sex workers, immigrants, the houseless, and other social outcasts).

Meanwhile, as in other parts of the world, so-called “molecular revolution” came to center stage with the rise of reproductive, environmental, and minoritarian struggles. Lurking behind this development were broad planetary crises of life and its reproduction, which the politics of the nation-state were no longer equipped to handle. It is here that the importance of the militant community movements must be situated, as they carry the problem of militancy, albeit in an atomized manner, through the shift of political climates that separates the long ‘68 from today.

In the 1970s and 1980s, as industrial pollution and excessive development intensified, Japan witnessed the increasing appearance of so called “inhabitants’ movements” (jyumin undō), i.e., groups of people who, in order to protect their lives and communities from threats of eviction, industrial pollution, and nuclear hazard, actively resist the capitalist state’s mode of development. Be they nomadic or sedentary, inhabitants are those who belong to the Earth, as opposed to residents who belong to civil society. Belonging to the Earth entails creating a singular rapport with a place (topos) by means of a collective project. Such a singularization of the environment forms a necessary condition for nurturing militancy in our current era. The richness of place-based militancy is exemplified today in the struggles of Chiapas, La ZAD, Rojava, as well as the movement to Stop Cop City in Atlanta.

In what remains, I would like to briefly highlight three inhabitants’ struggles — those of migrant workers, fishing town dwellers, and urban precariats — each of which displays the power of militant community movements in different modes and intensities.

(i) In major industrial cities in postwar Japan, there are ghettos called yoseba (“gathering place”), which are populated by day laborers. These include Sanya in Tokyo, Kotobuki-cho in Yokohama, Sasajima in Nagoya, and Kamagasaki in Osaka. In these yoseba, the most precarious stratum of the working population lives under the harshest of conditions. Violent oppression by labor brokers (mostly yakuza) and police is common. Given the severity of life, their struggles are always intense. Since the 1960s, spontaneous rioting has occurred regularly, the most recent episode of which took place in Kamagasaki in 2008. Although most of the Japanese left had made a habit of ignoring the lived struggle of day-laborers in yoseba, a decentralized group of revolutionaries intervened there during the 1970s and 1980s. These engagements inaugurated a tradition of radical underclass movements. Militant actions were carried out against the police-yakuza coalition, public spaces were occupied to shelter the houseless and organize support for the inhabitants such as health care and cookouts, festivals of underclass entertainment were convened, and so forth.21 Those who intervened in yoseba struggles believed that the existence of day-laborers formed the crux of the revolutionary impetus during this period. One of them, a theorist named Shūji Funamoto (1945–75), emphasized that these “fluid underclass workers” conceptualize militant power in a way that reflects their precarious social status, which ensured that their mobile, invisible but substantial solidarity networks stretched across the Japanese archipelago and beyond.22

(ii) In the history of industrial pollution, the mercury poisoning at Minamata is widely considered to be among the worst instances in Japan. Minamata is a fishing town on the Shiranui Sea, located in the southwest of the mining area in northern Kyushu. The pollution was inflicted by a state-backed chemical industry, the Chisso Corporation, that released methylmercury into the sea from 1932 to 1968. Poisoning by methylmercury damages the central nervous systems of all mammals; the effects are long-term and often fatal. The disease spreads widely across the oceanic area, moving through food chains from fish to animals and humans. For decades, both Chisso and the government ignored and denied the damage wreaked by the poisoning. Consequently, victims initiated struggles along various fronts, from medical research, court battles, victim care, and street protests. The rage felt by these victims, many of whom were incapacitated and unable to express it, was intense.23 Over the course of the long battle that ensued, the ultimate expression of protest was the presence of victims’ own mutated and dying bodies, wearing signs imprinted with the character 呪 curse.

(iii) In the early 1990s, the activist scene came to consolidate its existential ground, that is, as a collective “self-affirmation” (jiko-kōtei) of precarious existence. This was epitomized by a Tokyo-based group calling themselves the Alliance of Good-for-Nothings (Dame-ren), that would become a model for the larger community movement active today, Amateur Riot, that is in the midst of developing an East Asian network of anti-work movements.24 Their activities were based upon what they called “commingling” (kōryu), i.e., gathering and talking. The subjects were basically their life problems: difficulties in conforming to the workplace or school, poverty, depression, mundanity, substance abuse, and so on. Importantly, their effort to tackle these serious problems led them to develop a style of collective enunciation rich in humor and full of laughter. As an extension of commingling, they began to live in the same neighborhood, run a daycare center for those who have kids, and manage a bar-cum-social center. They experimented with a new way of life for the poor, a way good-for-nothings could survive. Though the group itself did nothing resembling a leftist movement, most of the members also participated in more radical projects and protests. After all, their jiko-kōtei was nurtured by the desire to transform their negative status in society into an affirmative power.

These inhabitants’ struggles developed a broad horizon of autonomous projects in the post-new left climate. In the course of this process, the principal agent of antagonism shifted: “activists” gradually replaced “revolutionaries,” being compelled more by their proclivities toward horizontalist principles such as equality, mutual aid, and the commons, or their sensibility for cohabitation, than by the will to revolt. This transformation pointed toward a return of all that the new left sects had suppressed and made invisible in their politics and discourse: care for the existence of comrades. As such, it entailed a change in the modes of subjectivation and organization from authoritarian to anti-authoritarian, sectarian to non-sectarian, revolutionary cells to activist collectives.

When we consider this shift from the will to revolt to a sensitivity for cohabitation, it becomes clear that the creation of a radical movement would necessitate both components. However, in the experience of Japan so far, one supplanted the other. Therefore, militant anti-authoritarian movements have not grown to be a substantial current as they have elsewhere. That is to say, the impetus to “change the world without taking power” has not materialized in a political movement. One of the reasons for this — an internal cause — is that the activist subjectivation was accompanied by an unwavering suspicion toward that of the new left revolutionaries, particularly given the way their collective will to revolt had been fashioned into an authoritarian militarist apparatus. As a result, the sensibility for cohabitation has tended either to momentarily bracket or permanently exclude the will to revolt itself. What is repressed in Japan’s oppositional struggle has switched sides, from sensibility to the will.

Oblivion of the Original Violence

After the end of the long ‘68, there were a select few moments in which Japanese struggles reverberated in sync with the cycles of global uprisings: the anti-nuclear movement after Chernobyl in 1986, the anti-globalization movement beginning in the late 1990s, the movement against the US war in Iraq in 2003, the uprisings after the Arab Spring in 2010, and recent protests against police violence after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, as well as the mistreatment of immigrants by the state. During these moments, the horizon of Japanese struggles opened itself up to the planetary impetus, as brief returns of its long ‘68.

The Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011 coincided with the global uprisings initiated by the Arab Spring. The two planetary catastrophes in different ontological registers encouraged Japanese activists to play a dual role: to protect the reproduction of the populace from radiation, and to protest the government and the Tokyo Electric Power Company. For two years, these projects exerted powerful effects. They accomplished the largest mobilization of indignation since the long ‘68, and prevented the government from restarting the nuclear plants for roughly two years. Eventually, however, an overwhelming sense of crises under the unending nuclear disaster enabled the return of conformism — “solving problems as a nation” — and the protests came under the control of JCP-related movements, which, in collaboration with police, and for the sake of their electoral campaigns, preclude all degrees of militant tactics by violently excluding anti-authoritarian radicals. In other words, a permeating conformism prioritizing social order encouraged the liberal parliamentalist movements to obstruct the activists’ attempts to empower the crowd on the street. Their interference became another factor — an external cause — preventing militant anti-authoritarian movements from becoming a substantial current. All in all, however, the imposition of legalism/pacifism has always been the modus operandi of the postwar status quo, from the right and from the left.

The coerced pacification of the populace originated, in the first place, in the constitution of the postwar regime itself, as the embodiment of the interests of both the US occupation forces and the Japanese ruling elites. The implicit groundwork that made the postwar regime possible lay in its oblivion of the original violence carried out consensually between the US and Japan, including Japan’s war crimes against the peoples of the Asia-Pacific Region and America’s nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In order for the two states to establish the defense pact against their common enemies on the Asian Continent, this double forgetting was institutionally imposed upon the populace by means of the constitution. Article One, which reinstates the throne of emperor as a national symbol, normalized the exemption of the Emperor’s war crimes; in consequence, the violence enacted by innumerable Japanese, including commoners, against the Asia-Pacific peoples went largely unquestioned. The principle of peace in Article Nine, which renounces the use of military force other than for self-defense, internalized an acceptance of the American violence against the Japanese, which was considered an inevitable tragedy, one that had already happened, and must be accepted as destiny.25

In the political context of the cold war, as the long-stretched islands of the Japanese archipelago were transformed into an advanced base for US military operations, Japan’s social stability became geopolitically vital. In this context, the pacification of Japan functioned in a paradoxical yet entirely fitting manner: while providing the Japanese nation with the exceptional gift of economic flourishing in a war-free enclave, it has simultaneously acted as a crux of US military apparatuses throughout America’s wars in Korea and Vietnam, and up until its recent tension with China.26

During the long ‘68, if there was a common desire that drove all the divergent and conflictual revolutionary groups, it was to undo the pacification made possible by this constitutive oblivion. At the time, there was a desperate sense that this undoing was the only way to change a society domesticated by, and subservient to, the global apparatus of war. The interaction between vanguardist militarism and empowering militancy took place on the common horizon of this desire. Although their violence against the state was comparatively minuscule relative to the great violence of the combined empires against the people, they effectively transformed their desire to dismantle the postwar regime into a collective will to revolt.

Amidst the bubble economy that accompanied the high economic growth, the closure of the long ‘68 was marked by a tendency to lose sight of the constitutive oblivion imposed by the dual powers.

The general mindset of the public learned to ignore the globality of the political horizon — the US, with Japan as its ideal client state, its well-behaved vassal — under which it had been made to exist. In such a context, while the history of the long ‘68 was buried in the national unconscious like a bad dream, the sense of affirmative subjectivation of popular struggle disappeared, replaced by a pervasive legalism in which empowering militancy with suicidal militarism were conflated and identified indiscriminately, as a single criminal act of terror. The pacified atmosphere of society was thus grounded upon a philosophical confusion of the ethical judgment of power with the moral judgment of violence.

Japanese society today rests upon an organic yet rigidly unshakeable regime of conformity. As such, rather than being recognized as a movement, any act that challenges it will be dismissed as pure crime. On the other hand, we have also seen that this society itself — as an assemblage of heterogeneous crowds — has moments in which it affirmatively opens itself up to newly emerging forces that allow it recompose itself differently, no matter how desperately the governance of capitalist-state seeks to confine it within the territorial mold of an insular nation.27 In such a climate, our task today is to recreate a culture of militancy that combines a sensibility for cohabitation with the will to revolt. Only then can the repressed experience of the long ‘68 be resurrected on a new horizon.

Images: Masami Arai, from 谺 [Echoes], 1970.

Notes

1. In January 2022, in Okinawa City, four hundred youths attacked the Okinawa Police Station. The event was provoked by police brutality. A 17-year-old high school student was harassed by a police officer while riding a motorbike, and had his right eyeball ruptured. Enraged by the failure of acknowledgement and compensation by the police, young people rose up. (More info here) In this event we sensed the inspiration of the 2020 George Floyd Uprising in the USA, but also the 1970 riot against the US military presence in Koza City, Okinawa. Unfortunately, there has not yet been any ensuing movement to build upon this impetus. In July 2022, former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was shot to death by Tetsuya Yamagami, whose family had been ruined by the religious cult of the Unification Church, which was known for its anti-communist activities and its collusion with Abe and other figureheads of the Liberal Democratic Party. Yamagami was arrested at the site. (More info here.) Soon after this act, the film director and a former Japan Red Army fighter, Masao Adachi, made a narrative movie “Revolution +1” (2022, 80 minutes) as a political intervention (online here). We will return to the Japan Red Army later in this article.↰

2. The periodization of “Japan’s long ‘68” was inspired by “Revolution and Retrospection,” Gavin Walker’s preface to The Red Years — Theory, Politics and Aesthetics in the Japanese ‘68 (Verso, 2020): “the ‘red years,’ the Japan of the long ’68 — and we might call it the longest ‘68 on earth, stretching from 1960–73, or even polemically from 1955–73.”↰

3. To illustrate this development, the concept of “schismogenesis” coined by Gregory Bateson is of use. The anthropologist developed the term in the 1930s, in reference to the social formation among Iatmul people in New Guinea. He conducted ethnographical observations on the differentiation of dress, behavior and emotional expression among groups of women and groups of men. He categorized two forms of differentiation: (A) complementary schismogenesis and (B) symmetrical schismogenesis. The former, frequently observed between men and women, tends to create submission. The latter, mostly observed among men, tends to invite endless competition. (He also identifies a third option to avoid these situations: “reciprocity,” a balancing by exchange of roles and “plateau of intensity” as the way of defying climax observed in Balinese culture.) The differentiation in either case is detected in various dimensions of sociality — individuals, classes, genders, generations, cultures and nation-states —in which both sides dissimilate each other, striving to become everything the opponent is not. See Gregory Bateson, Naven, Stanford University Press, 1958, 171,197; and Steps to an Ecology of Mind, The University of Chicago Press, 1972, 61, 72. The concept “plateau of intensity” was later adopted by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their A Thousand Plateaus — Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated by Brian Massumi, University of Minnesota Press, 1987. See also David Graeber and David Wenglow, The Dawn of Everything, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021, 56, 58.↰

4. In his On Insurrection [Hanran Ron] Hiroshi Nagasaki, a key member of Bund’s Tokyo University cell during the 1960’s anti-Ampo struggle, developed a theory of revolutionary politics rooted in the bitter experience of Bund. Casting doubt on the historical necessity of revolution, Nagasaki insists on the importance of the event of the spontaneous uprising. It was this position that bridged the two peaks of rebellion during the long ‘68, from the political movement for national empowerment in 1960 to the anarchic rebellion of heterogeneous forces in the late 1960s. See Hiroshi Nagasaki, On Insurrection, Gōdō Shuppan, 1969.↰

5. Gan Tanigawa (1923~1995) was an influential poet and political organizer of the early ‘60s. He played a leading role in creating a connection between the 60’s anti-Ampo and the coal miners’ struggles. In his 1956 text “The Origin that Exists” [Genten ga sonzaisuru], he stresses that the epicenter of energy to change society and the world exists in village communities, since “the pre-proletariat” who reside there are the true agents of revolutionary struggle. This position was later criticized as a romanticist retroversion by several far-left ideologues of the late ‘60s. But his thought and practice continues to be admired by many today. ↰

6. Kazue Morisaki (1927~2022) was a poet and author. She was involved in Circle Village and Taisho Miners’ Struggle with Tanigawa. She wrote many books, documenting coal miners’ communities and local women’s lives, contributing a great deal to the women’s liberation movement. Michiko Ishimure (1927~2018) was also part of Circle Village with Tanigawa and Morisaki. Thereafter, she came to be engaged in the struggle against the Chisso Corporation on behalf of mercury poisoning victims in her native town of Minamata, a fishing village in Kumamoto Prefecture, Kyushu. The site is internationally known for its high incidence of mercury poisoning, whcih consequently is known as Minamata Disease in Japan. ↰

7. For instance, see Kristin Ross’ writings on La ZAD, No-TAV and Les Soulèvements de la Terre in La forme-Commune – La lutte comme manière d’habiter, La Fabrique Editions, 2023. ↰

8. See the well-known documentary series by Shinsuke Ogawa and his production team Sanrizuka—Heta Village (1973). ↰

9. To be clear, however, the farmers’ movement itself experienced internal conflict later in the early 1980s. For example, see William Andrews, “Sanrizuka: The Struggle to Stop Narita Airport” (online here); and David E. Apter and Nagayo Sawa, Against the State. Politics and Social Protest in Japan, Harvard University Press, 1984. ↰

10. To pursue the problematic around militarism and militancy further would lead us to a series of binaries related to both “language” (commanding discourse versus collective enunciation) and “organization” (the party for mass mobilization versus the groupuscule for networking of communities and affinity groups). These oppositions ultimately concern a pair of concepts that Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari articulated as “molar” (a tendency toward concentration, centralization, and totalization) and “molecular” (dispersion, decentralization, and singularization). Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus – Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated by Brian Massumi, University of Minnesota Press, 1987.↰

11. The new left sects also participated in the campaigns of Zenkyōtō, with the exception of Kakumaru-ha, which kept its distance from them, and Minsei, which obstructed them.↰

12. This tendency was observed not only among politically leftist artists (e.g.., the movie directors Nagisa Oshima and Koji Wakamatsu), but also the fascist novelist Yukio Mishima, who committed harakiri suicide at the climax of his highly performative coup attempt in 1970. See Jonathan Watts, “Dead writer's knife is in Japan's heart,” The Guardian, 24 November 2000 (online here).↰

13. The desperate situation was most explicitly expressed by the slogan of the Red Army Faction, “pre-stage armed uprising,” which encouraged all militants to take up arms such as guns and bombs and create a revolutionary situation here and now, instead of waiting for it. ↰

14. Although they had no direct connection with the JCP at the time, they used this name to stress their authenticity as a true communist party in Japan. ↰

15. See the film: “United Red Army” (2007), directed by Koji Wakamatsu. The narrative allegedly follows the event faithfully, by contrast with the dramatization observed in other films or novels.↰

16. See the film: “Red Army/PFLP Declaration of World War” (1971), directed by Masao Adachi.↰

17. See the film: “Looking for the Wolf” (2018), directed by Kim Mirye. ↰

18. There is an epilogue of solidarity between these two groups. In 1977, Nihon Sekigun hijacked a Japan Airline flight 472, after taking off from Dhaka. In exchange for hostages, they demanded the release of nine imprisoned members of the ultra-militant groups, including two from Higashi Ajia Hannnichi Busō Sensen (HAHBS). This attempt succeeded and six were freed in Algeria. They joined Nihon Sekigun in their global operations. Since then, three of them, including Yukiko Ekita from HAHBS, were arrested in different places, and sent back to Japan. Ekita was released from a Japanese prison in 2017. More info is online here.↰

19. See Postmodernism and Japan, edited by Masao Miyoshi and H.D. Harootunian, Duke University Press, 1989. Alexandre Kojève, Introduction to the Reading of Hegel – Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit, translated by James H. Nichols, JR., Cornell University Press, 1969; Roland Barthes, Empire of Signs, translated by Richard Howard, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1982.↰

20. The project was called “Remodeling the Japanese Archipelago,” initiated by the Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka in 1972. ↰

21. See the film: “Yama – Attack to Attack” (1985), directed by Mitsuo Sato and Kyoichi Yamaoka. ↰

22. Shūji Fumanoto, Do not Die by the Roadside in Silence [Damatte Notare Jinuna], (Renga Shobō Shinsha, 1985, 168 and 169).↰

23. The complexity of their struggles against pollution, industry, and state are meticulously described in Michiko Ishimure’s novel Paradise in the Sea of Sorrow: Our Minamata Disease, (The University of Michigan, 2003). Ishimure was also a participant in the coal miners’ struggles.↰

24. For more info, see here, here, and here.↰

25. The notion of peace involves ambiguous elements: although military actions are permitted only for self-defense, Japan nevertheless maintains substantial military forces (the 8th largest in the world) and continues to expand them. Furthermore, the interpretation of defense acts has changed, leading to an expansion of their range. This shift would make Japan America's collaborator, rather than simply its lapdog. Unsurprisingly, debates around its interpretation became a major dividing line in parliament, and demarcated Japan’s political horizons. An ambiguous pacifism has been the political stronghold of the liberal camp, which is designed as protection against the right wing’s attempts to officially declare a remilitarized nation-state of Japan. On either side, what is certain is that Japan will continue to increase its defense budget and sustain its military pact with the USA.↰

26. At this moment, militarization is going on in the Nansei Islands as a joint project of the US Military Forces and the Japanese Defense Forces. For more info, see here.↰

27. One of the emerging forces observed in increasing numbers are immigrant workers and students from East Asian countries, permitting frequent exchanges among the activists therefrom in Tokyo. This phenomenon reminds us of the role Tokyo had played as a gathering place for Asian revolutionaries in the early 20th century.↰