Locked Together

David Campbell and Jarrod Shanahan

Although we are often invited to imagine power relations as stark formal contrasts between Manichean poles locked into eternal conflict, the concrete life of power is full of uneasy compromises, tentative reciprocities, and functional arrangements between subjugating forces and the subjugated. Nothing better exemplifies this fact, and the role that such ambivalent entanglements and complicities play in cementing relations of hierarchical domination more generally, than the intimate violence of incarceration. Jailers and jailed, although quite literally “locked together,” nevertheless experience a wide range of fluid dynamics in their relations to each other. For this reason, not only can ethnographic attention to such spaces help to disabuse us of overly-simple portraits of power, but there is no one better qualified to engage in such forms of situated research than inmates themselves.

David Campbell and Jarrod Shanahan both served city-time sentences at Rikers for protest activity. They spent their time, and subsequent years, closely studying these institutions, and have assembled their findings into a rich ethnographic account of a social order forged, against all odds, by some of New York City's most powerless people, in one of its most hostile settings. The result is a new book entitled City Time: On Being Sentenced to Rikers Island (out now with NYU Press).

While most people behind bars at New York City's Rikers Island penal colony are detainees awaiting the settlement of their cases, a smaller population have already been convicted of relatively minor offenses and are serving sentences deemed too short for the state prison system. These stints are called “city time,” and range from a few days to a year. They are generally served within large, open dormitories lacking privacy and sanitation. Within these spaces, incarcerated people, who disproportionately represent the lowest rungs of the city's racialized working class, reproduce an elaborate set of rules, rituals, and relationships as a means both of survival and of giving meaning to the time taken from them.

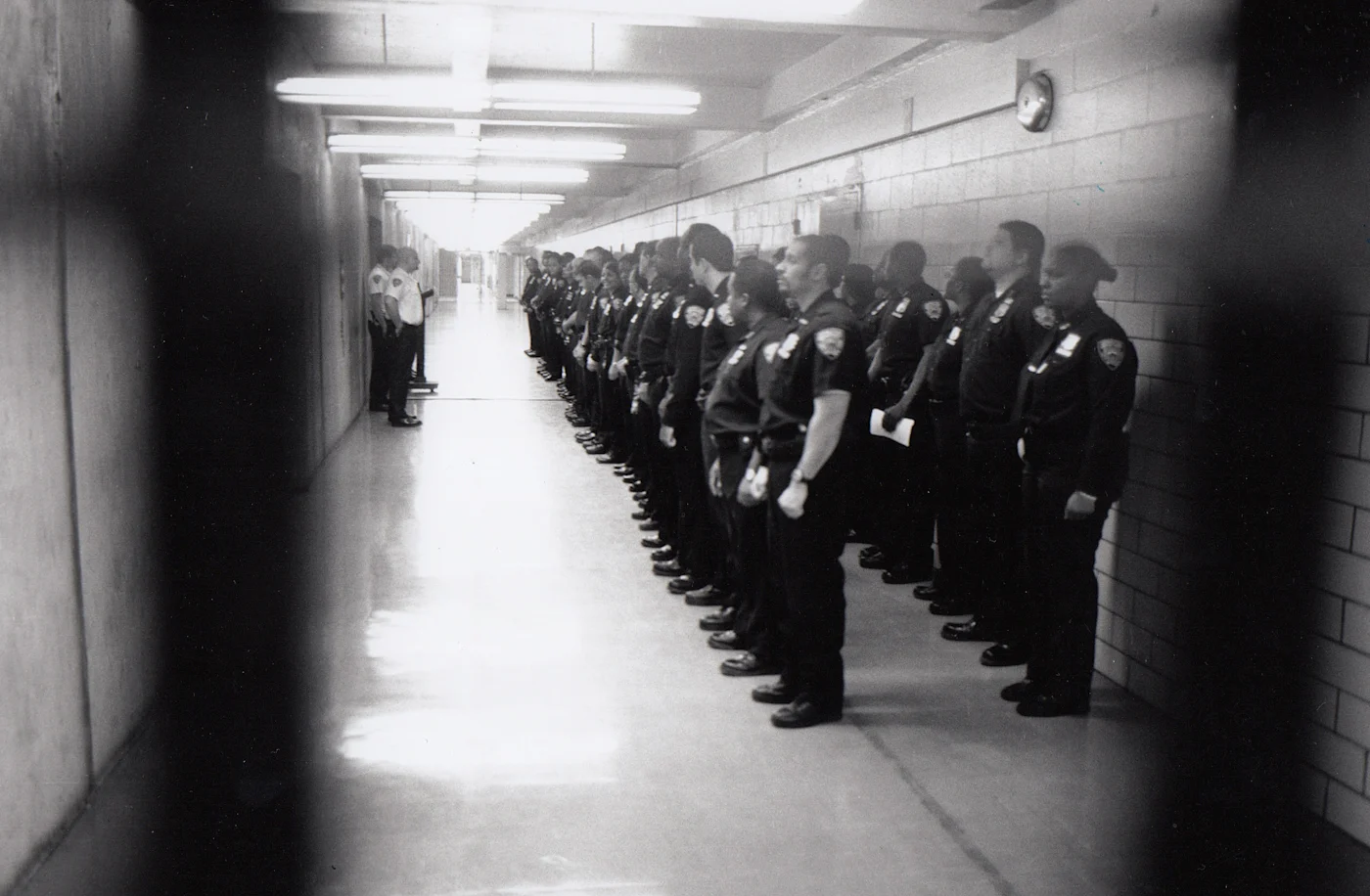

The passages excerpted below explore the contradictory relationship between city-time prisoners and their guards, who often hail from the same working-class communities of color and face each other at Rikers Island from different sides of the bars. Their daily interactions are at once antagonistic and cooperative, as each side seeks to minimize discomfort and maximize autonomy in the bleak environment where they spend their days.

For more of Jarrod’s writing, see our excerpt from his “Captives: How Rikers Island Took New York City Hostage.”

“Take that thing off your head,” the captain orders dismissively.

“Man, get the fuck outta my goddamn face,” his target shoots back without missing a beat.

On his head, he wears a ragged pair of white Hanes briefs, tied up like a durag with the elastic waistband reading “HANES” across the flesh of his forehead. He points at it, explaining, “This here is my motherfuckin’ religion.” As he calmly, steadily continues past the now-flabbergasted captain, he turns his head over a shoulder to call back, as if for added clarification, “Ain’t got time for your bullshit today!”

David and the other inmates on their way to breakfast cannot help but laugh at his brazen ploy.1 Invoking the specter of a religious discrimination lawsuit, however unlikely, was enough to make the captain drop the issue entirely, even despite the man’s humiliation of him. It is a truth any inmate learns after any significant amount of time: you have to use the institutional rules against the institution itself.

“Among themselves,” writes incarcerated author Jack Henry Abbott, “guards are human. Among themselves, the prisoners are human. Yet between these two, the relationship is not human. It is animal.”2 Put a bit less dramatically, in the words of former C-76 inmates Neville “Storm” Redd, “I have to get up day after day and look at someone every day having them tellin’ me when I can sleep, eat, or shit, and Storm don’t like people tellin’ him what to do and how to do it.”3 Despite the animosity built into their opposing subject positions, however, city-time inmates and COs are stuck with each other, and the functioning of the jail requires some degree of their cooperation. This means that within what we might call a state of low-intensity social war, some modicum of cooperation must be eked out.

The most stubborn fact of relations between COs and inmates is that underneath the uniforms that aim, quite overtly, to definitively establish and enforce their very different social roles, everyone is a human being. In undertaking their duties, COs demonstrate considerable variance in their individual personalities, levels of sympathy or antipathy toward the inmates, and enforcement of the jail’s rules (or lack thereof). But at the end of the day, with no respect to their individuality, the COs have a job to do — one that puts them at odds with the inmate. “For the custodian, control is the central interest,” writes sociologist Richard Cloward, “for the inmate, escape from material and social deprivation.”4 We can surmise that even the COs who smuggle contraband or otherwise break the law with select inmates spend most of their time enforcing the institution’s rules, in the interest of preserving the appearance of normality, especially if they are concerned with avoiding detection.

Relations between inmates and COs, therefore, assume the paradox inherent in many hierarchical institutions where people interact with each other as both human beings and representatives of the structural position they have been assigned. While these roles may be relaxed when things are going well, any slackening of the jail’s rigid inmate/CO division will not last long. When an inmate in Jarrod’s dormitory, who had been exchanging flirtations with a female CO, purchased her a sweet treat from commissary as a gift, one of Jarrod’s section mates remarked in disgust, “What kind of motherfucker goes to commissary and gets something for a CO? She got a helmet upstairs,” he continued, referring to COs’ riot gear, “and she gonna put it on and bust your head.”

Former Rikers CO Robin K. Miller recounts how the “newly hired correction officers are brainwashed and abusive seeds are planted by academy instructors, programming them to believe that a Rikers Island prisoner…is an animal, the enemy, [a] scumbag, and extremely dangerous.”5 COs are instructed in the basic arguments from books like Games Criminals Play, which instill within the recruit a sense that every overture from an inmate, ranging from social familiarity to a request for basic assistance, could be part of a complex con designed to seduce the CO into a life of crime. More broadly, CO culture is steeped in an us-versus-them mentality, which enforces solidarity among COs, lest one be considered an “inmate lover” — a term of derision concerningly similar to a segregationist invective against whites who dared cross the color line.6 This has a socially cohesive function for the CO workforce, but also helps COs dissociate from the injustices they witness, by recourse to, in the words of John Irwin, “the readily available theory that prisoners deserve their fate.”7

It would, however, be impossible for COs to go about their daily business in overt conflict with the inmates, just as it would be for the inmates to be in constant upheaval against the COs. Thus, some kind of uneasy peace is required. In practical terms, the easiest way for COs to keep a lid on the dormitory is to deputize the lion’s share of enforcing compliance to its most powerful inmates, the big homies and shotcallers. C. René West recounts how this power arrangement is called “running the dorm,” a term both of us encountered numerous times during our sentences. West reasons that it is impossible for COs to disrupt the de facto prisoner power structure, because they don’t spend enough time in the dormitory, and anyway, the prisoners in power are willing to back up their rules with violent force that inspires fear. “I try to do my job fairly,” West writes, “but the bottom line is I am going home and I can’t change anything in one day.”8

City time cannot be structured by brute force alone. This means the guard must work with the prisoner to make the institution function, and therefore must engage in reciprocity, making “deals” or “trades” with prisoners, and observing de facto protocols. Early prison ethnographer Gresham Sykes argues, “Despite the guns and the surveillance, the searches and the precautions of the custodians, the actual behavior of the inmate population differs markedly from that which is called for by official commands and decrees... Far from being omnipotent rulers who have crushed all signs of rebellion against their regime, the custodians are engaged in a continuous struggle to maintain order — and it is a struggle in which custodians fail.”9

Experienced COs know that recognizing the authority of a small inmate elite is bound up in their helping to keep other inmates in line, and enforcing the sustained order of the cell block or dormitory house. Smart COs even take an active role in shaping these dynamics, by choosing who they recognize as worthy of inhabiting them, through the institutional recognition that is often essential for their success. The end result of structural accommodation is a hierarchized and divided body of inmates characterized by privileged actors breaking the rules in exchange for enforcing docility and order where it matters.10 This arrangement can be quite explicit. Recall, a decade before David served his city time in C-74, the facility was made notorious by the disclosure of “The Program,” a systematic and organized extortion racket run through the cooperative effort of powerful adolescent prisoners and COs, resulting in the death of at least one young man.11 Shortly after David’s time, the disclosure of a similar arrangement at Rikers, dubbed the “World Tour,” revealed that little had changed despite considerable scrutiny of the deadly practice of CO-sanctioned prisoner violence.12

David was incarcerated with a man called Ra during one of Mod 4’s neutral and nonhierarchical periods. Ra was addicted to crack and homeless on the outside, but enjoyed some status in jail because he was so familiar with it. He had been coming to Rikers on and off for decades, and had served a couple of years’ time upstate, too. Though a big guy with a booming voice, he did not impose himself on others — he was generally pleasant to be around, could take a joke, and cleaned the place regularly for free. Yet he was also the kind of guy who wanted to avoid rocking the boat at all costs; more than anything, he craved stability. The COs seized on this as a chance to divide and conquer the inmates. When one highly combative new arrival once lost his temper at a CO and shouted “Suck my dick!” at him, Ra swooped in, raising his hands in the air, palms out, shouting, “No, no no.” Ra remained on the CO’s side, even after the CO began casually threatening to bring down a punishing search on the house — a threat everyone knew he was good for. In turn, Ra apologized and told the CO he would talk to the new guy. The next day, a search team did appear, but they only trashed the new guy’s bed.

On another occasion, an inmate’s expensive new sneakers disappeared after a search. He began filing grievance after grievance and complaining to any captain or dep who would listen, until Ra came back to the dorm one day and announced to everyone that he had just passed the security captain, who oversaw searches, in the hall. “If you don’t cut it out with them shoes, he said they coming back with a search and they takin’ everybody’s shoes.” One of David’s neighbors later grumbled some biting criticism of Ra: “If we was back in slavery times, Ra’d be one of them niggas helpin’ them chase other niggas down and shit.” None of this stopped Ra from adhering, at least in his mind, to some version of the inmate ethos of not snitching. Even this favored the institution; he and David once had a heated discussion about whether calling 311 to file a complaint about the conditions in the jail constituted snitching, with David arguing that you cannot “snitch” on a CO or jail in which you are captive, and Ra adopting the common CO position that this behavior made the inmate a snitch.

But CO cooperation with select inmates is not simply due to a divide-and-rule strategy. In practical terms, there are many times when the COs themselves are unable to function without the knowledge of those in their custody. The most obvious example is labor: during David’s time, a large-scale inmate strike left COs pushing mops, brooms, and food carts because there were no inmate-workers to do it. COs who are unfamiliar with a certain housing unit’s schedule will often ask the inmates what time a given event, like chow or yard, usually occurs. In Mod 4, the electrical wiring for the overhead lighting, controlled from a single light switch panel located in the Bubble, was hopelessly convoluted and counterintuitive. At lights out, COs unfamiliar with the house would try one switch after another. The lights would go on and off on each side, giving rise to shouts, jeers, and grumblings like, “These motherfuckers stupid.”

The CO often ended up asking an inmate to enter the Bubble and demonstrate how the control panel worked.

To maintain the balance of power in their favor, and to keep the whole operation cloaked in deniability, it is important to COs that they not seem deferential to the inmates. Preferential treatment is most covert when it assumes the form of selective enforcement of the rules, rather than the overt granting of special privileges. When COs see something they know to be a violation of the rules, they have the choice to take action or to act as if they have not seen it. COs are largely strategic in how they make this decision, and favoring certain inmates is part of the calculation. This pragmatic, relational approach to running carceral facilities has been dubbed “reciprocity.”

Reciprocity amounts to the generous use of discretion, creating a constant state of negotiation that asserts the authority of the COs more so than the written rules, especially when the two contradict.13 “In the authority to choose how to enforce security,” write scholars David Correia and Tyler Wall, “is an authority to make law itself.”14 Interestingly, one 1998 study of six long-term prisons in the Northeast discovered that COs were unlikely, if given multiple-choice questions, to describe their management of the jail in this way, but when they were asked open-ended questions, typically described some form of regular reciprocity as part of their approach.15

An incident from one of Jarrod’s dormitory houses is instructive on this account. Inmates smoked all day in 10-Upper, which stank of the unmistakable odor of Bible paper in a way the COs could not have missed. Given that the house was otherwise quiet, and enforcing smoking rules was largely a losing battle, the COs tolerated it as long as it did not become so blatant as to make them obviously complicit. Among themselves, inmates enforced basic rules: blowing the smoke out windows, not smoking too much at once, and masking the scent with homemade air fresheners. Inmates who were serious about their smoking habit took these rules seriously, as they enabled the daily enjoyment of one of the small pleasures of city time. And it was in everyone’s interest to avoid a shakedown, if for no other reason than to avoid the indignity and chaos they bring.

One day, a section of heavy smokers broke from the unspoken pact that kept everyone smoking in peace, and created a great stink. The B officer, responsible for patrolling the dormitory, visited their section and told them, almost apologetically, to keep the smoking to a minimum.

They ignored her and kept at it. Shortly thereafter, perhaps by coincidence but likely not, a captain came through and ordered them to stop smoking. Dissatisfied with their response, she stormed out. Several minutes later, like clockwork, the men heard, “On your stomachs, eyes on the window, and dream of home.” An armored probe team proceeded immediately to the section of smokers, and dumped all of their buckets and bedding into a big pile right in the middle of Broadway. The team insulted and berated the men, and confiscated a pair of boots that were the only shoes one man in the offending section had.

After they left, the smokers left the pile of bedding and commissary untouched for hours, in one final act of defiance. The other inmates in the back half of the dorm began to politely request that the mess be cleaned up, but the stubborn smokers refused. In response, an overwhelming and vocal consensus emerged that they should clean it up, since their section had brought the raid on itself by flaunting their de facto privileges and refusing to cooperate with the COs. The renegade smokers were forced to comply.

“The assertion that the ends of police violence are always identical or even connected to those of general law is entirely untrue,” critical theorist Walter Benjamin observed in the early twentieth century. “Rather, the ‘law’ of the police really marks the point at which the state, whether from impotence or because of the immanent connections within any legal system, can no longer guarantee through the legal system the empirical ends that it desires at any price to attain.”16 The violent actions of the police, therefore, do not simply refer back to any written general statute but constitute, in a creative and productive sense, the realization of the extralegal violence at the core of law itself. An adage among New York cops, dating to the nineteenth century, puts it more bluntly: “There is more law in the end of a policeman’s nightstick than in a decision of the Supreme Court.”17 These words are doubly true of the CO, who polices a population lacking even the flimsiest claims to due process. COs’ discretionary power is immense, and can furnish the final word on most questions, with no serious possibility for appeal. But it is not absolute.

In a 1985 study of five prisons, sociologist John R. Hepburn found considerable variance within individual workforces in how guards practiced power. Guards were likely to refer to their legal authority as a source of power, although it is unlikely many prisoners followed their orders for this reason alone. But guards also responded in large numbers indicating that they believed their power to also rest on the reputation they cultivated among prisoners for their competence, judgment, and treatment of them.18 David and Jarrod found this to be true of Rikers; COs who had a reputation for cutting inmates slack, or at least not going out of their way to give anyone a hard time, were respected, and in turn, their jobs were made easier.

David developed a rapport with the CO who served as his supervisor in C-74’s kitchen, who not only turned a blind eye to the extra food and spices David pilfered daily; he also allowed David to go to the yard while he was on the clock, sometimes offered him things like better food, and often paid David overtime no matter how many hours he actually worked (or didn’t). When David expressed his desire to quit his job to focus on writing and translation, his supervisor not only permitted him to quietly stop showing up to work (inmates are required to work, and therefore not technically allowed to quit); he even kept David on the payroll. When wages were slashed in August 2020, he began paying David overtime wages every week to make up the difference, even though David still was not actually working. This rapport and arrangement were due at least in part to David’s criminal case, to which his supervisor was sympathetic. At the same time, it served to ensure that David would not rock the boat at work by flouting any institutional rules too brazenly.

This sort of arrangement was not uncommon and usually seemed to exist as a sort of favor-giving from the CO to the inmate, sometimes with the expectation of reciprocity. David’s supervisor did ask David to snitch once, but kept the same arrangement even after David refused. Other COs developed more complex relationships with inmates, and might go so far as to buy them food from “the street” or even packs of real cigarettes, alcohol, and weed. Whether these things were given freely or with the expectation of pay was often unclear. (Payment, in cases like these, would be handled through outside intermediaries, not made in commissary products.) All of these things, even a slice of pizza, could be sold inside for enormous profit. Sometimes these relationships were based on gang affiliation; there were always rumored to be members of the Bloods, Crips, and Latin Kings on staff at Rikers, including very specific allegations about individual officers. Sometimes, though, favors were simply based on friendship, or something approaching it.

Other examples of “cool COs” include those who would assuage an inmate’s psychological pain by telling him he “didn’t belong here” or “shouldn’t be here.” Others engaged in various forms of play with the inmates, such as chess, trash talking the institution, performing impressions, joining jailhouse gossip, or sitting down in the day room to watch TV. One cool CO could often be found playing Xbox with the inmates in his dorm. That same CO often brought up the fact that he had been incarcerated for six months in Atlanta’s Fulton County Jail on charges that were eventually dropped, further burnishing his cool-CO credentials.

Some COs would try to relate to inmates in terms of racial or ethnic solidarity. One Black CO in C-76 sported a pin in the shape of a Black Power fist on the front of his uniform. A Black female captain once launched into a tirade against the 12-Lower Crips because they had been turning away too many new arrivals at the gate, declaring, seemingly without any sense of irony, how she hated to see “Black and brown people oppressing other Black and brown people.” Another captain, this one white and male, seemed to surprise an inmate of color with his candid and relatable demeanor. The inmate asked, “Captain, are you Spanish?”

The captain replied, “No, I’m white, but I’m Eminem white, not Donald Trump white.”

Cool COs engage in routine rule breaking. For example, the door between the changing area and waiting area for inmates receiving visitors at C-76 was supposed to be kept closed, with the inmates penned into a narrow hallway awaiting their visit. The main CO who oversaw this area during Jarrod’s time, however, liked to socialize with the inmates and kept the door open, allowing them to mill around the much larger intake area freely, cracking jokes, and reading the uncensored versions of the New York tabloids. On one occasion, as a captain passed through, the CO silently gestured for inmates to step back into their designated area and shut the door. Understanding at once what they were being asked to do, they all complied, right in time for the captain to observe that everything was being done by the book.

Just as cool COs quickly get a good reputation, inmates remember when COs needlessly give them trouble. These COs are often called “herbs” or “bozos,” New York slang for an uncool person. When Jarrod was in the pens awaiting release, the overseeing CO left the cell open during this basic routine of processing inmates’ paperwork. A captain walked in and commanded a waiting inmate to move his foot, which protruded by several inches, back into the cell. As he walked away the inmate remarked, “It’s two inches; Go Go Gadget had to say something. He knows he’s a bozo!” Another rejoined, “That nigga came into 7-Main, a guy in a knee brace asked him a question, and he ignored the questions and asked ‘do you have a permit for that knee brace?’” When the answer was no, “Go Go Gadget” had taken it away.

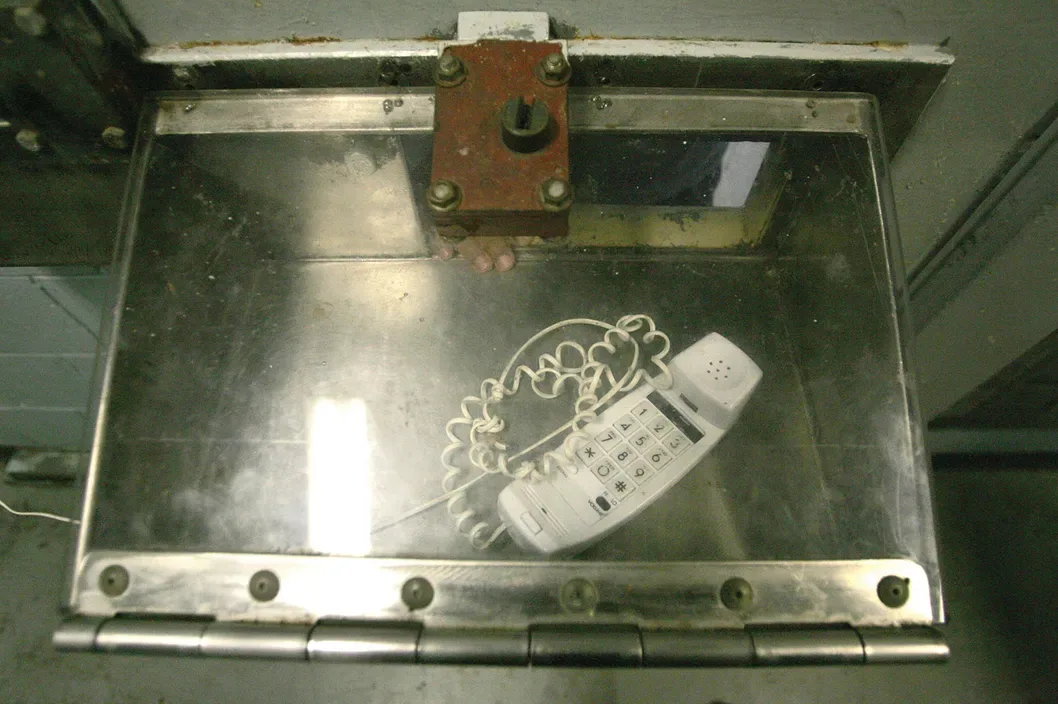

Herb COs have a much harder time of it than the cool ones. One CO, a white man with a heavy lisp named Festa, often had his speech impediment mocked by the inmates, many of whom referred to him as “Festa the Molesta.” As he made his rounds doing the start-of-shift head count, inmates would sometimes call out things like, “Yo Festa! Say ‘spaghetti’!” On one occasion, an inmate did not understand that Festa was directing him to reach into the immobile metal tray set in the wall separating the Bubble from the dorm, because Festa could not think of the word for it, and referred to it as “the…thing.” When the inmate finally figured out what he meant, he scowled and asked, “Why didn’t you just say the drawer?” Festa answered glibly that it was “more of a slot than a drawer,” to which the inmate responded, exaggerating Festa’s speech, “Well, why didn’t you say ‘schthlot,’ then?” Though cruel, these interactions presented a rare opportunity for the inmates to get the upper hand, even if momentarily. By extension, the practice of giving (often demeaning) nicknames to COs was a constant source of empowerment and comedic relief.

City Time: On Being Sentenced to Rikers Island is out January 7th 2025 with NYU Press.

Notes

1. From the Introduction: We are aware of the recent movement toward “humanizing language,” which trades loaded terms like “convict” for softer designations like “incarcerated person,” “resident,” or even “person with justice system involvement.” While this language poses the risk of inadvertently obscuring violent or uneven power relationships—as when police murders are euphemistically rechristened “officer-involved shootings,” or when Jarrod’s minimum-wage grocery-bagging job earned him the lofty title of “associate” — we nonetheless understand and applaud the imperative to humanize incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people, and have used this language wherever possible. We realize, then, that readers who prefer human-centered language may be disappointed to see that we generally refer to the incarcerated men we encountered during city time as “inmates.” Our reason is simple: this is how the men serving city time refer to themselves and each other, with near universality. Though we sometimes opt for “prisoner” or “incarcerated person” (and generally eschew “inmate” in favor of these terms in our other writings on incarcerated life), it felt both disingenuous and inaccurate to avoid the term “inmate” here, as it is, for better or worse, the language preferred by the vast majority of city-time prisoners we encountered.↰

2. Jack Henry Abbott, In the Belly of the Beast: Letters from Prison, Vintage, 1981, 60.↰

3. Neville “Storm” Redd, “Confused Anger,” in 7-Upper: Writing from Rikers Island, EMTC, through the Fortune Society, New York Writers Coalition Press, 2013, 35.↰

4. Richard Cloward, “Social Control in the Prison,” in Theoretical Studies in Social Organization of the Prison, ed. Social Science Research Council, Social Science Research Council, 1960, 22.↰

5. Miller, Inside the Dark Underbelly, 22. The term “brainwashing” appears fairly frequently in firsthand accounts from former COs, such as the Road to Legacy Podcast episode cited in chapter 2, “Rikers Island: Life and Experience of Two Retired Correction Officers,” and in the comments section of the DOC’s LinkedIn page.↰

6. Miller, Inside the Dark Underbelly, 26. ↰

7. John Irwin, Prisons in Turmoil, Little, Brown, 1980, 127–28. ↰

8. West, Caught in the Struggle, 105.↰

9. Sykes, The Society of Captives, 42, 55–57.↰

10. Cloward, “Social Control,” 32–45.↰

11. Brad Hamilton, “Brutal System of Teen Beatings Continues at Rikers Island’s RNDC Prison,” New York Post, May 6, 2012. Online here.↰

12. Stephen Rex Brown, “Rikers Island Correction Officers Run ‘World Tour’ Program Using Inmate Enforcers: Suit,” New York Daily News, November 16, 2020. Online here.↰

13. Denise L. Jenne and Robert C. Kersting, “Gender, Power, and Reciprocity in the Correctional Setting,” Prison Journal 78, no. 2 (1998): 166–85.↰

14. Alison Liebling, “Prison Officers, Policing, and the Use of Discretion,” Theoretical Criminology 4, no. 3 (2000): 333–59.↰

15. David Correia and Tyler Wall, Police: A Field Guide, Verso, 2018, 184.↰

16. Walter Benjamin, “Critique of Violence,” in Selected Writings. Vol. 1, 1913–1926, ed. Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings, Harvard University Press, 1996, 243.↰

17. Luc Sante, Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York, Vintage, 1992, 247.↰

18. John R. Hepburn, “The Exercise of Power in Coercive Organizations: A Study of Prison Guards,” Criminology 23, no. 1 (1985): 146–54. These results, as Hepburn indicates, largely square with Lucien Lombardo’s earlier study of COs at New York’s Auburn State Prison, Guards Imprisoned: Correctional Officers at Work, Elsevier, 1978.↰