Prelude to a New Civil War

Shemon & Arturo

Building off the analysis they set out in their articles this summer, Shemon and Arturo trace the mounting hostilities of our present moment back to the unfinished business of the first American Civil War and the counter-insurrection that crushed its emancipatory promise. Must the escalating violence all around us descend into a shooting war? To what extent does race continue to serve as a limit condition of our ability to imagine a free and dignified life in common in this country, beyond the dictates of the economy and the police? Must the liberation of a life in common proceed from a frontal clash, or does it look more like a decentralized processes of desertion and secession fragmenting the territory? Does revolution today look more like Reconstruction, the Free State of Jones, or neither? How does the new geography of conflict—no longer divisible into North and South, but traversing every city, every town—complicate our received image of civil war? If the rebellion this summer was a preamble to a new form of civil war, what are the vortices that allow its emancipatory potentials to deepen and expand, rather than trap itself in sacrificial black holes? While this essay attempts a first provisional sketch of the historical roots of our horizons, we hope it will serve as an invitation for others to throw out their wagers on the present.

Other languages: Français, Italiano

It was the proletarian general strike of the ex-slaves that truly put the final nail in the coffin of slavery. It is precisely this lineage of an emancipatory, liberatory, but nonetheless violent, civil war that needs to be updated for its second coming.

—Idris Robinson, “How It Might Should Be Done”

As indicated in poll after poll, op-ed after op-ed, more and more Americans are thinking about the present in terms of civil war. Why? The legacy of the U.S. Civil War is an obvious reason, but why is the specter of civil war raised so vigorously today? Why do so many people see the intensification of partisan conflict as inevitable?

This sentiment cannot be separated from the fires of the George Floyd uprising, which itself has unfolded in the context of decades of deindustrialization, the rise of mass incarceration, the 2007/8 economic crisis, escalating political tensions, the Trump presidency, and now the ravages of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has triggered a deepening of poverty and unemployment, but also anti-police riots across the country. The conjunction of all these events reveals deep splits within American society. Any strategy for revolution will have to account for the fraying and fracturing of the United States.

Since the beginning of the summer we’ve seen that Black proletarians won’t hesitate to riot in response to the murderous actions of the police. The anti-police riot coalesces into a multi-racial insurgency, which, in turn, provokes repression and counter-insurgency—and not just from the police, but also from right-wing paramilitaries, and even from moderates and liberals. The partisanship of this conflict presents itself as a choice between revolution and counter-revolution—are you for the uprising or against it? Does the ruling order deserve our respect, or not? The deepening of this fundamental tension raises the question of civil war in a concrete manner. The split—between those who are for the uprising and those who are against it—results not only in the fracturing of the unified bloc of whiteness, but fracturing among other racialized groups as well, including Black people, as was shown in the division between Black partisans of revolt and Black counterinsurgents. In the fight for life and dignity, the Black proletariat in motion splits society in a particular way, resulting in a form of civil war which is not just a matter of rhetoric or metaphor, but a real material contradiction that encapsulates the American form of class war and which is inseparable from race.

For now, civil war remains latent; it has not yet become a historical event. Still, the signs of mass polarization are visible everywhere: the politics of fear, paranoia, contempt, and hate is manifest in the everyday behaviors and opinions of large swaths of American society. It is less the fact of civil war than the threat of its potential that attracts and repels, expands and limits, inspires and frightens the collective imagination at present. Few say it in public, but in the privacy of their homes, Americans again ask themselves: are we on the eve of a civil war?

Interpretations

As the far-right sees it, they are building the forces that can intervene and put an end to the riotous behavior of the anarchists, communists, and antifa “terrorists” running amok in this country. In fact, a substantial portion of right-wingers believe that the George Floyd uprising was an early episode in a new sequence of civil war that most people have failed to acknowledge, either out of distraction or denial. Paramilitary formations like the Michigan Home Guard, the 3 Percenters and the Boogaloo Boys are some of the most militant forces on the right to take up this question. Moreover, the right-wing sees itself engaged not only in a paramilitary conflict against the radical left, but a cultural, political and economic fight to protect capitalism, national borders, law and order, and the nation-state as such from the hoards of immigrants, criminals, city dwellers and crazed leftists.

By contrast, the left generally avoids the question of civil war all together, which is its own way of relating to the matter—by fear and dread. Except for a tiny minority (e.g., Robert Evans’ “It Could Happen Here,” Kali Akuno, and the Revolutionary Abolitionist Movement), most on the left do not conceive of the present moment in terms of civil war, because the potential dangers are too much to bear. Since the overwhelming majority of guns are in the hands of right-wingers, many leftists worry that a civil war will inevitably lead to a massacre of the most oppressed. While one part of the left believes that they can prevent a civil war with a Biden presidency, another part is hoping that the riots will open up the possibility of revolution and that we can skip over a civil war. Meanwhile, the far right continues gunning down protestors and running them over with cars. It is no surprise that some leftists have had enough and are also coming to protests armed. The upcoming 2020 presidential election will only exacerbate these tensions, regardless of which candidate wins.

There is no imaginable scenario in which an electoral or policy fix succeeds in resolving the contradictions of the capitalist economy, the long crisis of U.S. capitalism, the devastation wrought by the pandemic, the persistence of racist police violence, and the heightening of political tensions. Now that another right-wing Supreme Court Justice is on the bench, avenues of legal change at the level of the Supreme Court are closed. The rollback of the gains of the 1960s is complete. This will lead to greater division and instability. Even if Biden wins the election, the far right will be inflamed, many of whom continue to view him as a Marxist Abolitionist—a hilarious mis-analysis reminiscent of the kind of thinking Southerners engaged in toward Abe Lincoln.

The Structure of Revolution in the u.s.

If the specter of civil war haunts the American psyche, this is because the U.S. Civil War was by far the most revolutionary, most violent, most divisive event in American history. However, because the concepts of revolution and civil war are often framed in opposition to each other, we forget that a social revolution did indeed take place. Black and white proletarians, temporarily united, carried out a revolution to overthrow slavery and then, during the Reconstruction period, undertook an even longer struggle to build an interracial democracy. As newly freed people struggled with former plantation owners, whites and Blacks created something akin to a commune in the Free State of Jones in Mississippi, while freed people took control of their destiny on the Sea Islands. At the same time, this revolutionary current triggered a simultaneous counter-revolution that played out over the course of the Reconstruction era, ultimately leading to the defeat of any semblance of interracial democracy.

While it is not remembered in this way, the American Civil War was just as revolutionary as the 1871 Paris Commune, the 1917 Russian Revolution, or the 1949 Chinese Revolution. Rather than socialism, anarchism, or national liberation, however, the synthesis of race and class revealed a uniquely American version of revolution, marked by the three-fold dynamic of civil war, abolition, and reconstruction. This emancipatory tradition is itself rooted in centuries of slave revolts, marronage, and everyday resistance to slavery.

Those looking for a European style anarchist or communist revolution will not find it in here. We are a country that has never come close to a revolution along these lines. However, we have had a revolution in the form of a civil war against capitalist slavery and white supremacy. Why was there never a communist or anarchist revolution in the U.S.? In our view, the answer to that question lies in the history of white racial domination in the U.S. While this conclusion might sound simplistic, it is derived from a profoundly complex analysis of US history. Revolutionary movements have consistently failed to overcome the white dominated racial order that defines the U.S. class structure, and for that reason the structure of class conflict in the United States continues to center around race.

While slavery was defeated, Black liberation was not complete. The defeat of chattel slavery heralded a century of Jim Crow legislation, while the fundamental social questions that the Civil War had raised—land, housing, education, healthcare—continued to be denied to masses of Black people. While the Civil Rights movement managed to remove many legal barriers, this only allowed the rise of a Black middle class compatible with the needs of capitalism and the state, leaving everyone else to fend for themselves.

The American Civil War remains unfinished. The fact that its specter has arisen again is no coincidence: race continues to mediate class, not only at the phenomenological level, but in the specific organization of class society. This tension is inherent to America.

What if instead of avoiding this contradiction, we engaged with it and studied it? Much of the radical left recognizes that race is central and constitutive of capitalism, but as soon as this is applied to class struggle and revolution, race fades away and dogma comes to the front. But if we see race as central to revolutionary struggle in this country, this changes the form that both take. In the spirit of Fanon, we have to “stretch” our analysis of class in order to make sense of the dynamics of race. When we do so, we can see that in the case of the United States, the demographic dominance of whites and their racism has shaped the contours of class conflict. Revolution, decolonization, abolition and Black liberation have appeared in the form of civil war precisely because of the specific configuration of class and race in this country.

Then and Now

Although the structure of revolution in the U.S. is determined by the dynamics of the First Civil War, it is a mistake to superimpose the past on the present. The United States is very different than it was in the 19th century. The first civil war had a rising bourgeoisie in the Republican Party and the North. They were riding the expansion of capitalism, carrying them well into the 20th century. There is no foreseeable dynamic paralleling that process today. The American bourgeoisie and capitalism are in severe crisis. The pandemic has triggered a new recession and a deepening of the downward economic trends that began during the 2007/8 crisis. There was no V shaped recovery then and there will be none now. Furthermore, the Democratic Party is continuing its course of neoliberalism, and Biden has denied every plank of the popular social movements: universal healthcare, the Green New Deal, and #Defund.

During and after the first American Civil War, the Federal Government provided the troops and material resources that defended Black people during Reconstruction. This certainly closed many radical horizons, but at the same time, was the only strategy free Black people could pursue. As long as masses of poor whites were not willing to fight alongside free Black people, the Federal Government was the devil Black people had to make alliances with. The legacy of Reconstruction has left behind it a powerful “Black” social democratic tradition rooted in mass movements, one which needs to be overcome. The only way masses of Black people can overcome this tradition is by seeing a new horizon open up through multi-racial insurrectionary struggle. This can simultaneously solve the race, the state, and the political economic question.

The first civil war was a contest between two distinct regions of the United States which both had industrial and food producing capacities. A modern day civil war would have a radically different geography. It would not be North versus South. It would be a conflict within each metropolis, each city, each town, each suburb, in each state and region. Of course, an intense polarization is to be expected in places like Portland and Seattle, where political conflict has been particularly pronounced of late. But conflicts will also emerge in smaller cities, towns, and suburbs with very little recent history of rebellion, as we already saw during the George Floyd uprising. Smaller cities like Kenosha, Rochester, Lancaster, have a larger concentration of racist whites and smaller sized police departments, making them some of the most volatile sites of potential civil war. Whereas in big cities people of color are a larger section of society, and racist whites tend to hide behind the police, in the small cities and suburbs BIPOC can find themselves surrounded by a sea of whites who are often ready to engage in extra-legal action in defense of capitalism and the state. These geographies are less likely to have gone through the civil rights revolution that transformed the bureaucracy, police forces, and governance of larger cities. Furthermore, in smaller cities, towns and suburbs, whites have experienced a collapse of white privilege, often resulting in deaths of despair. This growing immiseration is ripe for recruitment into the far-right, which blames immigrants and urban people of color for the downfall of society. A revolutionary strategy for civil war will have to split the white proletariat in these areas and win over a section of them to a revolutionary program for taking over the necessary means of production.

Let’s not have any illusions about it: the political and demographic divisions that pit cities, towns, suburbs, and the countryside against each other would be profoundly difficult to navigate in a civil war scenario. In this context, a revolutionary movement would have to win over the workers who are in the food and manufacturing industries. Many of these workers are not located in big cities, where people tend to work in retail, service, and logistical sectors, but in smaller cities, towns, suburbs and in the countryside. While these territories tend to be predominantly white, there are a significant number of people of color concentrated in agricultural and manufacturing workforces in these places. The labor force of the large farms where most food is produced in this country, for example, is largely made up of Latinx workers. These workers would be crucial in connecting gentrified cities to a process of socially coordinated production. The revolution cannot succeed by only taking over city squares, condos. bank headquarters, etc.

The classic relationship between city and countryside was the exchange of industrial goods for food. As cities have become bastions of real estate, finance, tourism, and other useless commodities, they can no longer participate in that relationship. The remaining industrial base surrounding the cities in suburbs and other spaces most likely do not produce all the exact goods that farms need. For a revolution to succeed, we would have to coordinate production on an international level between the international proletariat and the vast proletariat in the United States.

As the geography of revolutionary struggle spreads beyond major cities, what will link these vast territories together? Will it be organizations, social media, cars, crisis, or the rising tide of mass struggles? It will probably take a combination of all these forces and elements in new and creative ways weaving strong and lengthy threads that cover hundreds of miles. The vast size of this country certainly plays a powerful political role in keeping proletarians separate from one another. Is it possible for militants to use cars and the highway system in order to coordinate and organize the forces of insurrection on a regional and national level?

The Latinx Proletariat

Whereas the first civil war was basically a Black and white affair, the second civil war would be much more complex. The greatest demographic difference between the first civil war and the second civil war is the growth of the Latinx proletariat. As of today, Latinx people account for 18.5% of the population, and there are more Latinx people in the country than there are Black people. To the extent that Latinx proletarians make up a disproportionate part of the agriculture sector, what they do in a revolutionary crisis will be decisive, since they have the potential to counterbalance the racism of the mostly white countryside. The Latinx proletariat could play a vital role in jump starting a revolutionary form of social reproduction because they are in exactly those industries which will be needed to feed the revolution.

Masses of proletarians from Latin America have migrated to the so-called United States and have become a cheap labor force for American capitalism, working in the lowest paying jobs. They are hunted by ICE and under the constant threat of deportation. The abolitionist framework of the uprising is ripe for resisting ICE and other apparatuses of deportation. Antagonism with ICE has been a feature of the overall uprising, as we’ve seen in California and Oregon. Even before the eruption of the George Floyd uprising, undocumented prisoners were already protesting in response to poor sanitary conditions in ICE detention centers.

Yet, at the same time that they occupy a highly precarious position within the US class structure, Latinx proletarians are simultaneously wooed by whiteness and can display strong anti-Black tendencies. No one wants to be Black in America. Every immigrant is taught all kinds of anti-Black garbage. Much of the immigrant rights movement and their emphasis on immigrants being good, law abiding, hard workers easily slips into anti-Blackness.

Like all sections of the working class, the Latinx proletariat has many contradictory tendencies. The term “Latinx” itself is a loose and fairly broad term, one which fails to capture the internal dynamics and contradictions of any community that might be defined as such. Alongside divisions of gender and class, national divisions result in fairly different political and economic relationships to capital and the state. Another important contradiction is how Latinx US citizens view undocumented immigrants. There is a sizable portion with papers who view undocumented immigrants as criminals who skipped the line. These and other contradictions will have to be worked out in the process of mass revolutionary activity.

While much of our analysis focuses on Black and white relations within the proletariat, it is undeniable that the Latinx proletariat would be a decisive force in a civil war scenario, particularly because so many Latinx workers currently work in some of the most important industries in the country, especially farms and food processing centers. While we are inspired by the fact that a layer of Latinx proletarians participated and fought alongside Black and white proletarians in the George Floyd Uprising, the continuation of this shared struggle and the deepening of their reciprocity is not at all guaranteed. To begin with an assumption that darker skin color automatically translates into political unity is a gross simplification. Nor does shared oppression always mean unity. Like all proletarians, the Latinx proletariat is faced with a choice: join the uprising, abstain from the uprising, or attack the uprising. This choice will inevitably be framed in terms of whiteness, solidarity with Black liberation, citizenship, borders, and work. How the Black movement navigates each of these specific fields of struggle will have a powerful influence on what Latinx proletarians decide to do.

The Social Revolution

How does crisis impact the development of a revolutionary movement? Is the present escalation of political tensions doomed to become a proxy war for different factions of the bourgeoisie, or a shootout between giant armies? Or can we transform the current crisis into a revolutionary war to overthrow capitalism? How will things change when tens of millions do not have enough income, food to eat, and money for rent? What is the relationship between civil war and revolution?

In the course of its struggle against the ruling class, any revolutionary movement is forced to defend itself against the state and the forces of counter-revolution that seek to protect ruling class society. Any attempts to challenge power will always be met with repression and violence, which must be countered in order to further intensify and expand the revolutionary struggle. As we can see today and throughout history, the tension between revolution and counter-revolution gives rise to a latent civil war which risks eventually exploding into open shooting war. The question is how to engage with these polarizing dynamics in a manner that topples capital and the state and expands the realm of mass participation in the social revolution.

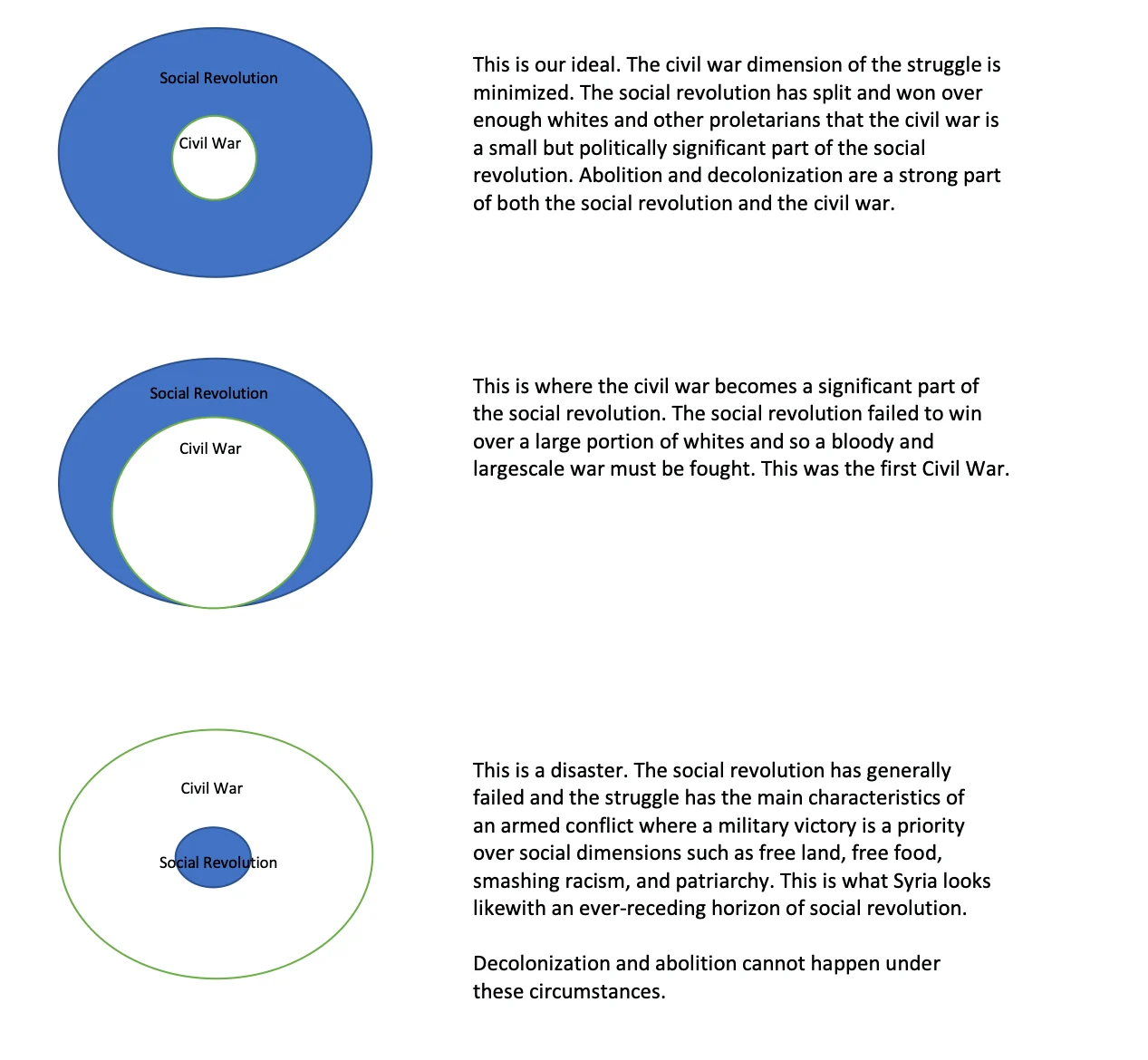

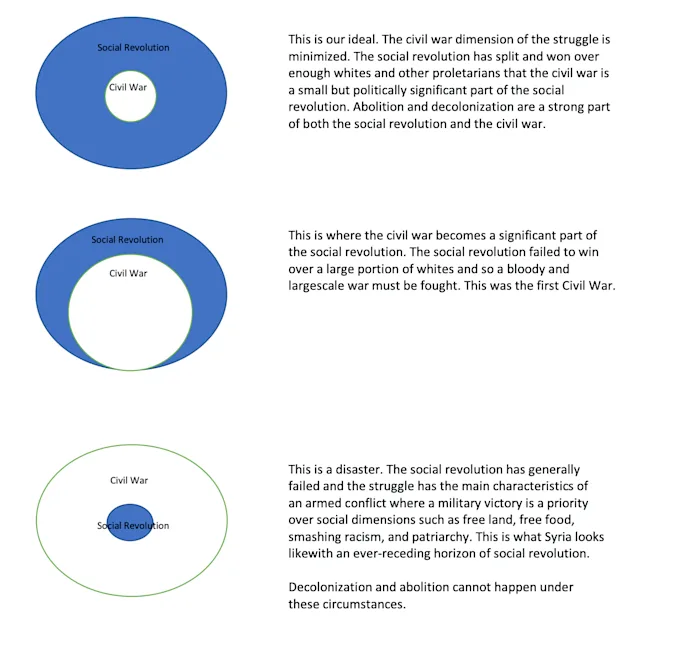

Social revolution, while inseparable from the civil war, is its own distinct process. The shape that social revolution takes is determined by the methods by which proletarians fight, their selection of targets, and their political imagination. Concretely, this means smashing commodity relations by taking over the necessary institutions and sites of production and creating a classless system of social reproduction for everyone involved, and in which wealth is no longer indexed to labor time. The social revolution entails not only the mass self-activity of the proletariat in its struggle to take over the infrastructure of society, but also the manner in which it captures people’s imagination and wins over the overwhelming majority of people to the the end goal it imagines for itself: the end of capitalism. By involving as many people as possible in the process of taking over society, the social revolution reduces the scope and scale of a potential civil war. In this manner, the fate of the civil war and social revolution are inversely linked.

While the U.S. Civil War entailed a revolt of property (in the shape of Black humans) against the slave power, today the revolutionary subject is a proletariat hunted by police, and facing the grossest inequality in generations, which will have to confront the spectacle of a fully commodified society. That the preamble to what might become the second civil war started with an anti-cop uprising makes sense in a moment where the state’s social welfare services have retreated, while its repressive apparatus has ballooned in the last fifty years. At the same time, many participants also came out during the uprising because of the economic effects of the pandemic, their hatred of Donald Trump, and because it gave them a way to finally fight back against this system. These and other grievances were all poured into the container of the George Floyd uprising. The container cannot hold all these issues, and that is why things will continue to explode. How the container explodes matters. In one version the demands of Black liberation will be forgotten or watered down—abolishing the police, prisons, jails, and the rest of the carceral apparatus will be sidelined. In the second version all movements carry forth an abolitionist perspective and there is a deepening of the process of social revolution. In this version, abolition is not a set of reforms to defund the police, prisons, and military. Revolutionary abolition is a class war on all portions of society that seek to monitor, discipline, and control proletarian life. Abolition cannot happen without a social revolution that destroys capitalism and the state. This connnection is not hard to imagine, as police continue to evict people from homes, protect grocery stores and warehouses from hungry proletarians, and murder Black proletarian and other working class people. However, the official BLM groups have not grasped this class dynamic at all, and generally try to contain the movement into an ethnic patronage system.

The actual uprising, where strikes, riots, the takeover of hotels, and the creation of autonomous zones occurred — this is the way forward. In this sense, the embryo of revolution already exists in the present, and our task is to connect with it and to engage in forms of direct action that can help it grow in a more strategic direction. Either these struggles will spread into new forms of mass action such as general strikes, blockades, seizure of means of production, etc., or the movement will become isolated and will be defeated. We feel that ultra-left communists and anarchists can play an important role in this process, even if the broader movement will most likely not understand itself in terms of anarchism or communism. Instead, it is more likely that a revolutionary movement will see itself as finishing the civil war , under the resurrected banner of abolition.

“We Don’t Have the Guns, We’re Not Ready”

The U.S. is the most heavily armed society on earth. The number of firearms owned by private citizens overwhelmingly exceeds those owned by the police and military. This passion for firearms stems from the legacy of settler-colonialism and slavery on which this nation was founded. Today, the majority of guns are not in the hands of people we would consider friends or comrades. This is a difficult fact. On paper, a shootout would result in a quick defeat of our side. But the success of revolutionary movements cannot be tallied by a simple accounting of who has the most guns. If that were the case, the Vietnamese would have never defeated the U.S. military, nor would the slaves in Haiti have stood a chance against Napoleon’s army. No dictatorship would have ever been overthrown in history. And yet it is undeniable that these things have happened and continue to happen.

Revolutions are not shootouts between good guys and bad guys. A successful revolution will not come from a vanguard of armed revolutionaries but from millions of everyday people engaging in riots, strikes, occupations, and other forms of mass struggle. We will not all of a sudden buy more guns than the right. Instead, it is the political divisions the movement can cause in society that can radically change the mathematics on guns. This means splitting the white population, yes, but most importantly, it means splitting the National Guard and the armed forces, and winning a section of them to the side of the revolution. Not only will these forces have the guns, but they will know how to use them and know how to train others. To this end, we should exploit openings within the rank and file of the military. During the Vietnam war, soldiers—Black soldiers in particular—rebelled against their officers. More recently, during the uprising this summer, National Guard units refused orders to attack protesters and instead put down their weapons. Moments like these need to be engaged with and taken seriously. Building alliances among rank and file soldiers can destabilize the repressive power of the state and will be crucial in determining the outcome of a revolutionary conflict.

While taking over the crucial means of production needed to feed, clothe, and care for everyone, it will also be necessary to defend these units of production from the forces of counter-revolution, which of course includes the police, but also a hardcore of racist civilizans who will defend capitalism to the end. This racist core must be overcome and destroyed in the process of a social revolution that splits the military, splits white society. In this sense there will be a need for guns, but the balance of forces does not rest on who has more guns. If the latter should not be a basis for political decisions, this is because that kind of math can only lead to one conclusion: we do not have many guns, so we should cool it. On the contrary, the balance of forces will be fundamentally decided by the mass character of our movement, our ability to seize key points of production, and our ability to project the most emancipatory set of politics we can imagine. Defending the gains of the revolution will require some proletarians to organize as armed groupings. Armed security forces have been a feature of the George Floyd uprising, so this is already happening to an extent. But if these groupings become specialized armed groupings, they risk isolating themselves and instituting a new form of social control, and in the worse case scenario, they risk becoming a “revolutionary” police force, a “people’s” army,” and a “worker’s state.” This would lead to the demise of any revolutionary process. If the armed struggle becomes a militaristic struggle of one conventional force against another, the insurgents will only become a new kind of state, a new ruling class, a new phase of capitalism.

Conclusion

The history that sheds the most light on the current moment is the era of the Civil War. This history powerfully informs the trajectory of the present. The Civil War, abolition, and Reconstruction are the unfinished business of this land. This is ‘Amerikkka’—our destiny has always been civil war. Revolutions in general are inseparable from civil wars and we see no reason why that will be any different in the future. To run away from the impending civil war is to run towards liberalism and social democracy, i.e., towards white supremacy. We have no illusions that most will balk at what we say, but just like the first civil war, you do not have a choice. The structure of race and class in the United States makes civil war an inevitable aspect of any revolutionary movement. The more aware we are of this phenomenon, the better we can navigate it and connect it to a process of social revolution. At this point, however, it is the far right that is determining the terms of this protracted conflict. A Biden Presidency will not change this fundamental dynamic. Whether or not the far left will develop a coherent strategy of escalation of its own is still unclear. Luckily, a full-blown civil war will not happen tomorrow. There is still some time to prepare.

Many will say that civil war isn’t on the table because nowhere among the ruling classes do we see a serious or large faction pushing for this. At the current moment this is correct. The divisions have appeared on the ground first. But this would be no different from the first civil war. It was the self-activity of slaves running away, abolitionists partaking in decisive direct actions, and the broader issue of the expansion of slave territories that drove the dynamic. Not until late in the game did the respective ruling classes finally accept the reality of civil war. In this sense, to seek the roots of the second civil war at the level of the bourgeoisie is a mistake. The seeds of the Second Civil War will grow from the ground upwards, as they did the first time around. In fact, the bourgeoisie will likely be the last class to accept that revolution and civil war are upon us. This is because it has the most to lose.

Our fundamental belief is that for any proletarian revolution to take place in the US, white supremacy and the racial order have to be thoroughly defeated. This struggle threatens to spark a civil war splitting all of society. It remains to be determined whether whites killing each other over Black Lives Matter has begun to change minds. Where the question of race is concerned, Black proletarians don’t necessarily trust either white proletarians or non-Black proletarians of color. Only by intensifying and deepening the dynamic process that tethers the question of revolution unavoidably to that of civil war can the contradictions surrounding race be settled once and for all.

We have spelled out in broad terms the strategies that may minimize the civil war and expand the social revolution. Large sections of the proletariat would have to develop an organized response to the crisis of capitalism: this will largely depend on our ability to seize, defend, and transform the industries that are necessary for social reproduction. The exact details of how this will be done can only be answered by proletarians acting and thinking on the ground and on their own initiative.