Pulsation, Flesh, Color

Elsa Dorlin

How can we use art to expose and confront the fantasy worlds that underpin counterculture? This is the problem posed by French feminist philosopher Elsa Dorlin, best known for her celebrated book Self-Defense. A Philosophy of Violence (an excerpt is here). The focus of Dorlin's article is a series of images produced by photographer Estelle Hanania during a 2024 exhibition at Haus am Waldsee in Berlin, which featured performances of stage plays by the French-Austrian artist and choreographer Gisèle Vienne.1 The aim of the exhibition, entitled This Causes Consciousness to Fracture, was to “trace the dreams and abysses of adolescence and counterculture.” For Dorlin, Vienne’s plays Crowd, L’Etang, and Extra Life depict “the world of discarded peoples, of damaged bodies” through which “alert and lively lives, the children in us” undergo a “crass violence” that leaves us with our lives “in smoking ruins.” This is the routinized violence of our everyday misery and oppression, the “shocks” that comprise the “ordinary fare of our lives.” In Vienne’s work, however, Dorlin perceives a movement of counter-hegemonic reversal: rather than freezing victimized bodies into static monuments, they engender a “counter-shock” that disrupts our sedentary perceptions of abject life, punching holes that “allow us to perceive the real that is usually sheathed by the dominant ideological machine of artistic representation.” For example, far from being a purely formal consideration of taste, the use of color betrays deeply historical prejudices. In this case, Dorlin argues, it becomes a terrain through which maneuvers are conducted: by blurring the inner and the outer, the high and low, Hanania and Vienne position counterviolence at the threshold between the incommunicable intimacy of the lived body and its political surface targeted by power. In this way, they enact a phenomenology of vital self-defense that calls us to seize upon the lived duration of our lives, bringing our senses into proximity with the (precarious, stubborn, and hazardous) vital irruption of the real.”

—Ill Will, August 2024.

In the style of a graphic novel, Estelle Hanania and Gisèle Vienne give us a different story to see. The photographed works are those of Gisèle Vienne, to be sure, and yet the photographs of Estelle Hanania and the montage by the two artists show us, tell us, a new narrative; as if the actors, reprising their roles on glossy paper, were coming to life beyond the original choreography, as if they had stepped out of it and offered us the key to a subtext. A subterranean text returning to the surface, as it were, after having traversed the live creations, and recomposing itself into a new work, in plain view of its two authors. The actors perform a different story — their part in it — and impart it to us. Addressing first the choreographer, who is no longer the sole author — it is with Estelle Hanania that she receives this narrative; they are its keepers here. The construction of this book begins, then, with this radical break: the authors position themselves not from the point of view of a demiurge, but as the custodians of an utterly novel work; they listen to the images, capturing tales of life — on the fly so to speak. What do they tell us? What do the skin, the gestures, the faces of these performers say? Why and by what are their bodies moved, shaken, cast down, or enlivened? What is the meaning of their upheavals? Here, photography is the creative subject, but a creative “eye” interpellated by its own creation, enjoined to clear a space/time for perception, enjoined to look, the better to hear what these works have to tell it.

Photography and montage as chore-o-graphy

One mustn’t expect the photographic series of Estelle Hanania assembled in this book to track or explicate the progression of the original pieces. They don’t attempt to translate them into another medium; they won’t be able to say more about them or say it better. Hanania and Vienne’s photographic reflection becomes choreographic in the sense that it reconstitutes a crucial moment of the continuous process of creation. Their method is not instrumental, it is formative of a different modality of the art of choreographing. Hence it is not just a matter of writing movement, but of grasping the movement itself, of reading it at the instant it begins to recount, when it addresses its universe of meaning in its own grammar. In this way, Estelle Hanania counters the socio-historical function of photography, that of investigation, the pursuit of truth, the capture of the real supposedly without mediation. She processes the still image not in order to arrest the dance, to freeze the action and decrypt it, to purify it or cleanse it of any wayward subjectivity, of any impetus resisting the artistic direction, but to look carefully and listen closely, to alert the senses, slowing down our spectator’s perception. There is a citational relation here with the slow motion that Vienne calls upon in her works, that art of the slow gesture deployed to its critical degree, which doesn’t artificially aestheticise what it exhibits with a voyeuristic intention, but which obliges us to be vulnerable to what is being played out in front of us, facing us with no other choice but to deal with the drawn-out enduring of others’ duration. Photography here is a slow motion pushed to its paroxysm: it doesn’t betray the body, exposed as spectacle, it has no patience with the tranquil place of those who watch without being seen, consuming the performance that is staged for them to see; it challenges us as to the effects of communing with the raw reality of lived experience and movement, of suspended emotion.

In the process of choreographic creation, the tempo and speed of the pulsation cause a rupture. They augment the movement, create something like an extreme shift in the cadence, break it off, slow it down or accelerate it like crazy, bring it back down to its primary elements or take it to its limits — they put it back together. In Vienne’s work, the pulsation is always a political address. It makes it possible not only to suspend for a time the passivity of the senses of those attending the performance, but more radically still, it creates a sensorial experience that is always synesthetic, capable of scrambling the coordinates of perception, the violent frame of intelligibility that disciplines and disfigures it. The pulsation is thus cinematic and carnal, musical and rhythmic, choreographic but also chromatic; and this is what the photographs of Estelle Hanania have captured in vivo.

A work within the work, this book as chore-o-graphy follows a serial form: two–three, two–three, two–three…, which takes us into its storyline from the start. Is it a matter of different points of view on a tale that we realize will henceforth remain untold? Is it the materialization of a revealed, confided narrative — like the archaeological layers of the same past event, danced, narrated, commemorated — which sometimes disappears, then comes back, from one image to another, signifying it differently, plunging more deeply into its signification or projecting it into a present? Is it the structure of the narrated itself, the text and the subtext, the known and the unsaid, as if an imaginary, unconscious chorus (composed of an ensemble of voices, intimated by the placement of the vignettes), illuminated, were chanting the intertwined history of the protagonists, the heroines, or talking to itself in an internal dialogue?

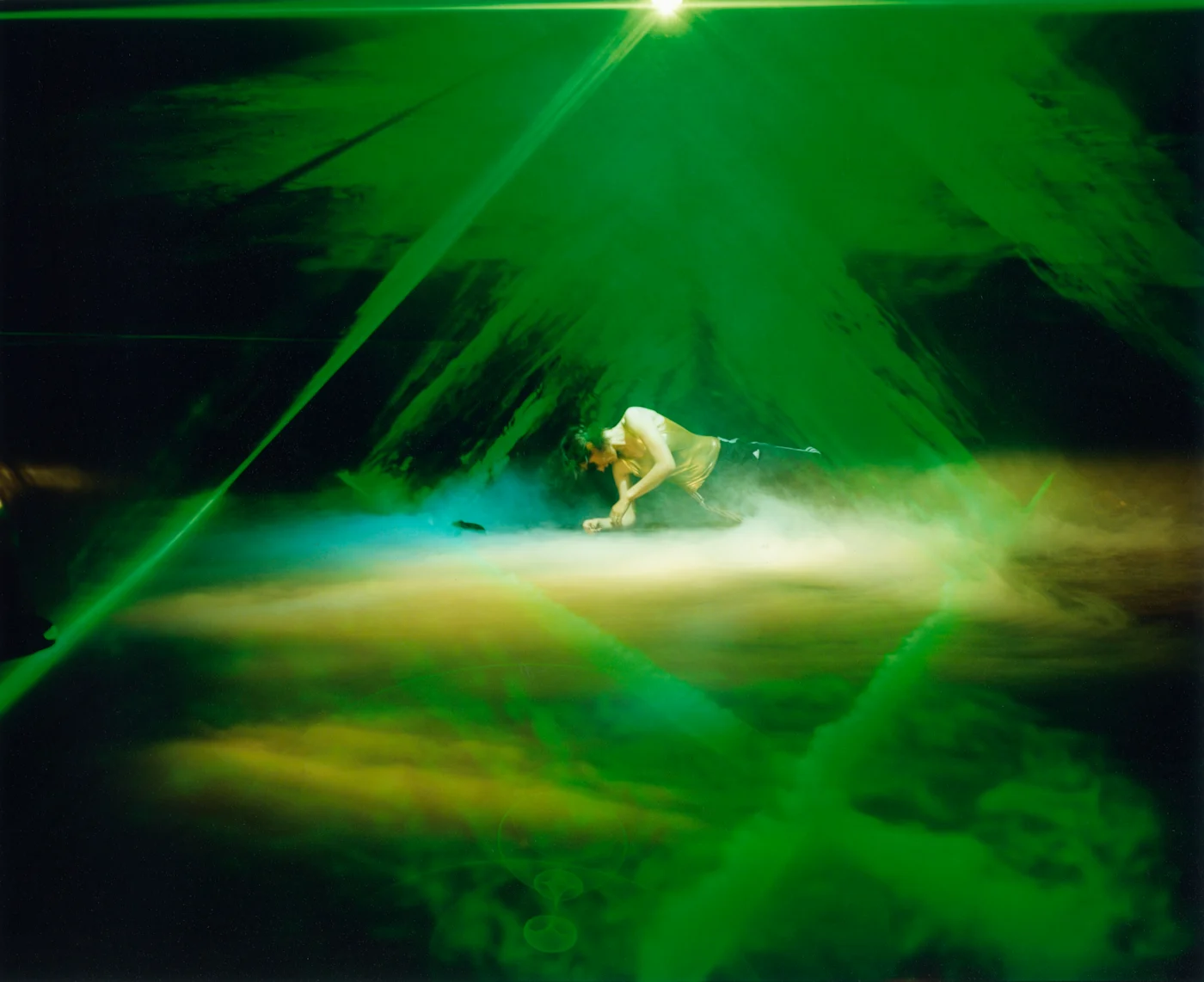

Spontaneously, naively, I recall the classic Sallie Gardner at a Gallop—that sequence of black-and-white photographs representing a horse and its rider, taken by the experimental camera of Eadweard Muybridge on June 15, 1878, in twenty-four snapshots. The purpose was to determine whether a galloping horse is at certain moments suspended off the ground (with no point of contact) — considering that to the naked eye, that information is imperceptible. In that instance, the search for scientific proof was supposed to be provided by the emerging photographic technology. If the Muybridge series appears to resonate with the work of Estelle Hanania, this is by echo and contrast: on one hand, the same question — what is the truth of the photographed subject? On the other hand, a deviation, a gap, a rupture. What is the truth of the subject, indeed, seeing that it eludes the photographer who doesn’t claim, no longer claims to have exposed that secret at the expense of the photographed being and event that inhabits it. In this book, the revisited “gallop” dispositive is closely related to two limit experiences/experiments of Vienne’s thought process. On one hand, the puppets, the marionettes with their arrested movements, are doubly frozen, texturized by Hanania’s photographic lens in a particular emotion (a tilt of the head, the depth of a look, the posture of an arm, a leg, a skin hue, the choice of an accessory worn forever). On the other hand, the experiences/experiments with light literally constitute a work that is shared between Vienne and Hanania, based on the light creations which Vienne has produced in collaboration with Patrick Riou and Yves Godin, for Crowd (2017), L’Étang (2020), and EXTRA LIFE (2023). For example, the use of a laser that one finds again in these pages, of light punctuated by blinding flashes (a use opposite to that employed these days by the police to hamper the freedom of information and the recording of state brutality during demonstrations) has the aim of not intervening directly in the explosive impetus of the movement on stage, of not interfering with it but of jostling our perception-reception; of disrupting, of fracturing the spontaneity of our own movement. Similarly, by flash-lighting the body as if it were the content and the form on and in which it appears, Estelle Hanania and Gisèle Vienne break down the movement into its elements, they illuminate it, make it stand out without ever altering it. The photography here is a mixed medium that is already cinematographic: it freezes a moment, forever; and at the same time, laying hold of lived duration, the pulsation of the lights, colors, and textures—animate or inanimate—brings our senses into proximity with the (precarious, stubborn, and hazardous) vital irruption of the real.

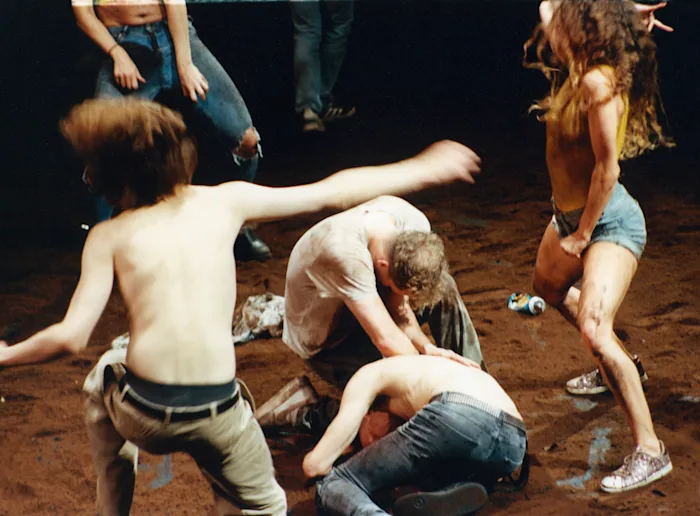

The language of colors — an art of chromatography

The colors of this book leap from the page. To tell the truth, they were the first thing that got me. Imposing, radical, raging. They’re one of the main characters of Estelle Hanania’s photographic renderings, which highlight the work of Gisèle Vienne and her collaborators. This work and this chromatic research appear as a major component of the pulsation, of the extraordinary narration that she re-transcribes while unveiling a life, or lives rather: a protracted adolescence, a party in the night — infernal and carnivalesque, clandestine and mystical, intimate and political — the dawn that breaks to an odour of tears, vaginal discharge, blood, and sweat. In the promise of an early morning, streaked with eye-liner strokes and yellow clusters of car headlights, the eyes fixated or staring into space, the belly heavy with bruises and words, one body speaks, cries out, then two, then three. In step with the narrative, melancholy, suffering, and rage intermix with love, tenderness, and desire, imprinting on our own bodies the erotic power of an embrace, transforming before our eyes these sensual connections into political revolts. This speaks for thousands, millions. They recognize one another, intertwine, fall apart together, console each other, confide in one another, wound each other, and rise up angry together. They resist death; they will go to the limits of themselves. This story is that of crass violence, the violence that leaves us with our lives in smoking ruins. The colors are not there to overexpose a scene so that only the essential is visible. On the contrary, they densify the flesh, amplify the sound and the rhythm so that the cries pierce through — cries of despair and rally. They are not the scenery of the characters, but are right there beside those who are commonly depicted as speechless or condemned to utter confessions, admissions, whisperings.

Finally, enveloping the bodies, the colors offer other coordinates to the visible and especially the audible, other forms to the memorable and the intelligible. They are the world of discarded peoples, of damaged bodies; they are the home, the library where the alert and lively lives, the children in us, the spectres of possible becomings. This chromatic ecosystem contends more or less porously with a traumatic, ghostly, and unreal atmosphere that is ever-present. The color palette of Hanania and Vienne thus constitutes a counter-shock that reveals the infinitesimal, ensilenced, solitary forms of resistance gathered into a repertoire of precarious but incarnate and actual insurrections. Certain critics write that Gisèle Vienne “aims to shock,” without understanding that shocks are precisely the ordinary fare of our lives and they form the order of the world. The “counter-shock” intention contributes therefore to a counter-hegemonic effort, an art of counter-violence that punches holes which allow us to perceive the real that is usually sheathed by the dominant ideological machine of artistic representation, with violence at its core.

Gisèle Vienne’s work favors black and white as backgrounds against which the colors, along with the moved and moving bodies, play the primary role. She writes the intimate and political movement of the body with the colors. There is the diaphanous, morbid white of the living dead, that of the puppets’ skin, of the victims that haunt the set; or the dazzling, electric white of the décor of L’Étang. This, too, is the equally oppressive white of the family and the immaculate draperies of children’s rooms, that of incredible patriarchal cruelty, of incest. And then, there is the sublime black of the Austrian forests, displayed in Vienne’s work, out of which terrifying silhouettes come into view; or the intolerable blackness of Jerk’s soul (2021). Different is that of the nights of Crowd or EXTRA LIFE — a deep and ambiguous black. It is beautiful and impure, luminous and dirty, of a density just as disturbing as it is exciting. It is a scene within the scene, which suggests, in a particular place and for a moment, a universe where everything is possible, all is permitted, where everything shatters and repeats itself, struggles and falls to pieces. This black is also a sensation, a heat that warms us, that welcomes dissociative confession: a black that tricks the temporality, so that “redo sense and redo body”’ expresses all the harshness of that which resisting requires, of that which surviving means.

Hence the content of the works outstrips the purely formal choice — it always makes sense, it cowrites the work itself — here again, it dictates a text, its text. In the photographs of Estelle Hanania, the black and the white make it possible to highlight the bodies that stand forth on stage in order to express themselves; they even become the privileged interlocutors with whom the players and characters engage. And just like these, sharing this same status, there is the yellow and the orange, the red and the pink, the green, the blue, the grey, and finally the brown (earth, skin, and smoke). The work upon the color material is decisive here: the photographs and their serial montage remind us of how much tonalities, but also and especially the chromatic medium, offer an infinite range of meanings. The pure, dazzling light, from one scene to another, one photograph to another, makes way for a dense, murky light, where the use of the overpowering laser is foregrounded, placing us in a novel cerebral state, forcing our ocular movements, and confronting us with buried traumatic memory, as in an unsanctioned therapy. The lights of a smoke machine, with their changing colors, themselves serve the same function of subjective panic — by disrupting the coordinates of space/time, by modifying the depth of field, by condensing the past and the present, by confusing our sense of high and low: a cloudy sky descends to earth with the turning of these pages; a beached sky that covers and uncovers phantoms, prone shapes, that prevents the headlights of a car from piercing a deeply buried truth.

Estelle Hanania’s photographic work makes this chromatic reflection more salient than it’s ever been, joined as it is to that deployed in Gisèle Vienne’s creations, where the colors play a role, their own role, strictly speaking. They enact a choreography: they impose their movement and their language. They contest each other, insinuate themselves into the language of the action and the sweat, the costuming and the accessories, the décor and the scenic space. In this book, Crowd is both totally Crowd and no longer quite that, as if the photography, via the colors, inserted in a different, pulsed narrative, the bodies lifted up in a trance, clustered, suspended, in erotic, intimate communion, paired or in threes … or the bodies stranded, stretched out on the ground. This choreographic kaleidoscope is followed by an arrogant gold as a reference point, that of a leotard breaking through the dark night of EXTRA LIFE, reconfiguring EXTRA LIFE in terms of a new temporality, now intimately connected to L’Étang and to Crowd. Beyond their material expressions, the colors reveal another narrative, embodying throughout the book a different phenomenology of duration: they are the incarnate colors of lived life. They stand for the encoding of the phenomenal experiences of the real. And this interplay of colors enables us to grasp the framework in which perceptions and perspectives are established and imposed, are disciplined; and the assemblages by which the perspectives and perceptions can be deconstructed or destroyed, or liberated and reinvented.

In his historical work on colors, Michel Pastoureau has devoted a sequence of works to black, to red, to green, to blue, to yellow, to white.2 A plunge into this history of colors sheds light on the photographic intentions of Estelle Hanania in this book as well as in the works of Gisèle Vienne which replay differently there. Note that this illumination doesn’t involve an analysis of the symbolism of colors, seeing that one of Pastoureau’s first lessons consists precisely in recalling that there is no transhistorical and apolitical symbolic register — or metaphysics — of colors. The history of colors is cultural and global: unstable, impermanent, and contentious. Hence their meanings, like the system of signification in which they have been mobilised, have not been the same from place to place. In Modernity, they have always followed an open, complex, conflictual, and contradictory course, due to the class antagonisms, the marks of gender relations, and Western imperialism imposing its codes, its knowledges, its values, and its sensitivities to subalternised cosmogonies. In the present case, distancing symbolism doesn’t mean totally forgoing it, but placing back at the centre what constitutes an artistic and political position-taking when it allows us to see and feel a flaming yellow, a violent red, a sensual earth-brown, a ghostly grey. As for myself, in writing these lines, with my cultural and social conditioning and the path my thought has taken, I cannot help but interpret this palette with what was already close at hand. Finally, the power of Estelle Hanania and Gisèle Vienne’s work derives from their way of working with, on, and against our cultural and aesthetic complicity, of radically decomposing perception into these elements so as to expose — not to escape — the phenomenal brutality of the current violence, and to posit a phenomenology of counter-violence, an aesthetic, a choreography, of vital self-defense.

Translated by Robert Hurley

Images: Estelle Hanania

Notes

1. Dorlin’s article appeared in a book collaboration with photographer Estelle Hanania and artist Gisèle Vienne, entitled This Causes Consciousness to Fracture (Spector Books and Haus am Waldsee, 2024; edited by Anna Gritz, Estelle Hanania, and Gisèle Vienne; text by Anna Gritz and Elsa Dorlin; design by Natasha Agapova. 180 pages, German/English/French, 152 color images, 31 x 31 cm, hardcover; on site at Haus am Waldsee and Georg Kolbe Museum). All photos are by Estelle Hanania, from performances of Crowd and Extra Life. Performers in the photos: Katia Petrowick, Adèle Haenel, Theo Livesey, Philipp Berlin and Marine Chesnais; dolls by Gisèle Vienne.↰

2. Michel Pastoureau, The History of a Color in six volumes: Black, Green, Red, Blue, Yellow, and White (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009–23). ↰