The End of Biopolitics:

Giorgio Cesarano and the Biological Revolution

Lorenzo Mizzau

Other languages: Español

The year 1968 was the year of the Great Divide. —The Club of Rome, The First Global Revolution1

The final map of the conquered planet has provided [capital] with the diagram of its imminent end. From the terminals of computers, the sums of its history flow into the system’s brain: the accounts balance, but they are Marx’s accounts. —Giorgio Cesarano and Gianni Collu, Apocalypse and Revolution2

When it rains, when there are clouds of smog over Paris, let us never forget that it is the government's fault. Alienated industrial production makes the rain. Revolution makes the sunshine. —Guy Debord, A Sick Planet3

The birth of biopolitics

It was probably Edgar Morin, in the early 1960s, who first made consistent use of the term biopolitics. However, the entry of biopolitics into the set of fundamental categories of the human sciences should, strictly speaking, be dated to 1968. That year, the Organization for the Contribution to Life (OSV) launched the publication of the Cahiers de la biopolitique under the guidance of civil engineer André Birre.4 In the journal’s first issue, the editorial team paints a rather grim picture of the reasons — or rather, the emergencies — underlying its publication:

[I]f humanity wants to continue evolving and reach a higher plane...it must purposefully restore its respect for the Laws of Life and cooperate with nature, instead of seeking to dominate and exploit it as it does today. [...] This way of thinking, which will enable us to reestablish order in an organic way and allow and techniques to reach their full potential and demonstrate their effectiveness, is biopolitical.5

A relationship of cooperation, the journal’s editors conclude, must therefore take the place of human domination over nature. Redefining the relationship between humanity, life, and nature here appears as the essential condition for the elevation of the human, which must coincide with a restoration of order. To this end, it will be necessary to develop an entire range of knowledge and techniques capable of limiting human praxis, adapting it to the “laws of life.” According to the Cahiers, then, biopolitics is essentially an operational and applied knowledge, capable of setting boundaries and establishing limits with a view to enhancing civilization.

But it is only with the second, more substantial definition formulated by the Cahiers that we catch sight of what might be called the dark side of biopolitics — precisely that aspect concerning the relationship between civilization and the regulation of human intervention in life. "Biopolitics," writes Birre, "has been defined as the science of the conduct of states and human communities in light of natural laws and environments and the ontological givens that govern life and determine men’s actions."6 In this definition, the properly political aspect of biopolitics comes to the forefront. Behind the regulatory aspect of biopolitics — understood as a technique for managing the human-nature relationship — lurks the properly geopolitical ("science of the behavior of states") and security-oriented ("[...] and of human collectivities") nature of its program.

1968: the end of separation

But there is another reason to take 1968 as the emergence moment for the problematization of the life-politics nexus. It was in 1968 that, under the pressure of a force that I will provisionally call "revolutionary," the relationship between life and politics was called into question, reasserted, and radically reconfigured within the sphere of action of the proletarian and student movement. Paraphrasing the Situationists, we could say that the need to put an “end to the separation”7 between life and politics — the immanent political nature of life and, conversely, the vitality that marks true politics — became self-evident, an immediate fact placed before everyone’s eyes, or, to recall Raoul Vaneigem’s evocative expression, a “basic banality.”8

Perhaps the clearest testimony to this, even before the distinctive clusters of signs that make up the period’s pamphlets and books, lies in another class of signs, namely, the subjectless communicative flows discontinuously distributed across urban spaces, and materially embedded in them: graffiti. It is no coincidence that a famous Italian slogan from 1968 reads, “The walls speak.”

Consider this brief list of slogans that appeared on Italian and French streets that year: “Ne travaillez jamais” (“Never work”); “La noia è controrivoluzionaria” (“Boredom is counter-revolutionary”); “Prenez vos désirs pour des réalités” (“Take your desires for reality”); “Vogliamo tutto” (“We want everything”); “Siate realisti, chiedete l’impossibile” (“Be realistic, demand the impossible”); “Contro la depressione, fate la rivoluzione” (“Against depression, make revolution”); “Non rivendicheremo niente, non chiederemo niente. Noi prenderemo, noi occuperemo” (“We demand nothing, we beg for nothing. We take over, we occupy”).9

These slogans all speak of the need to revoke a separation or dichotomy (work time / free time; reality / possibility; reality / desire; political / personal; social / psychological). This revocation expresses itself, above all, as a refusal of political delegation, of recognition and demands, which in turn would capture and isolate immanent politics within the separate sphere of representation. At its core, this revocation aims to dismantle partitions and antinomies, displacing opposing terms onto the plane of immanence that Deleuze, in his final text, linked to life itself.10

It is in a second group of slogans that the immanence of life and politics — the emergence of this plane — comes fully into view. In tags like “La vita è altrove” (“Life is elsewhere”) and “Lasciateci vivere” (“Let us live”), the term “life” is emptied of its conventional meaning and linked to the revolutionary semantics of immanence. In the inscription, “No agli specialisti della rivolta, sì ai rivoltosi della specie” (“No to specialists of revolt, yes to rebels of the species”), a conception of political revolution led by professionals stands opposed to the diffuse movement of a revolution emanating from humanity as a species. Finally, the famous slogan “Sous les pavés, la plage!” (“Under the cobblestones, the beach!”) reveals the principle of a new political ecology, inseparable from an ecology of desire.

What takes shape in these slogans is something akin to what Walter Benjamin, in his essay on surrealism, called an “imaginal space.”11 Overflowing with meaning to the point of rupture, graffiti explodes onto the surfaces of the metropolis, reconfiguring urban spaces. In doing so, it produces and reproduces an “innervation” of the collective body, which corresponds to the “revolutionary discharge” expressed in the continuous propagation of signs and gestures. This is what Benjamin spoke of as profane illumination: an insurgent continuum produces signs and images of desire that together coincides with the production of an insurrectionary collective body.

In this sense, the profane illumination of 1968 (or, 1968 as profane illumination) was not so much a collective consciousness or a deliberate project of rearticulating the relationship between life and politics, but rather the very emergence of this link, its irruption onto the plane of immanence — a new coordination of lives, bodies, politics, and desires, the rise of what Marx called the “real movement.” This is why Jacques Camatte, reflecting on 1968 during the new wave of upheaval in 1977, could write that “in May-June 1968 […] the impasse in which we find ourselves was clearly revealed.”12 Is it possible that this impasse still names the core of the politics we live in today? With the conclusion of the era of political representation — or of Capital’s “formal domination” — comes the evident collapse of politics onto the terrain of life, in its dual meaning: ecological (“the discovery of the importance of living beings”) and biopolitical in the strict sense (“the pressing problem of overpopulation”).13

However, it was the Situationists who, following in the footsteps of the young Marx, emphasized the third aspect of the life-politics nexus. For Raoul Vaneigem, author of the most famous and comprehensive synthesis of the thought and imagination of 1968, The Revolution of Everyday Life, politics must be displaced so radically into the realm of daily life — of gestures and desires — that “those who talk about revolution and class struggle without referring explicitly to everyday life, without understanding what is subversive about love and what is positive in the refusal of constraints — those people have a corpse in their mouth.”14

In this sense, in the age of cybernetic capitalism and pervasive cultural industry, revolution and politics could be understood only as a poetics of everyday life.

The capture of life-politics

The hypothesis I would like to put forward here is that 1968 constitutes the historical cipher of a life-politics constellation. In other words, 1968 names what Nietzsche called an Entstehung, i.e., the point of emergence, the origin of a phenomenon — an origin that is, in itself, "divided," "cut through," and traversed by struggle. "Emergence," as Foucault writes in his reading of Nietzsche, "always arises in a particular state of forces" and is, in this sense, "a place of confrontation"; it is a site of origin only insofar as it is, at the same time, a "non-place," a pure distance that simply marks "that adversaries do not belong to a common space."15

The life-politics nexus is thus the stake of a battle, one that was fought in the non-place we call 1968, and that generated heterogeneous discourses and incompatible codifications. This battle produced both victors and defeated: a victor who, in Nietzschean terms, gained "the right to impose names,” and a defeated whose knowledge, overwritten by the hegemonic discourse, was relegated to the background of history, buried in the lower layers of the historical palimpsest. A knowledge that was thus buried, "subjugated," yet always available to be dug up — always ready, as Foucault reminds us, to rise up.16

Biopolitics is only one of various names attributed to the emergence of the life-politics nexus. The discourse of biopolitics, in other words, is a codification of the insurgency of life-politics within the real movement. Is it possible that the range of discourses emerging from what has been called the "biopolitical turn" (bioculture, biomedia, biolegitimacy, bioaesthetics, bioeconomics, bioinformatics, etc.) — the proliferation of new fields of knowledge concerning the relationship between life and politics — are all grounded in something like an original repression?17 If the hypothesis I have formulated is correct, then it should be possible to trace the signs of this repression, to uncover the act of overwriting through which biopolitics itself came into being. What, within the life-politics nexus, is excluded by the code we call "biopolitics"?

Even a cursory survey is enough to recognize that the principle excluded from biopolitical discourse is, quite simply, revolution. If, in 1968, revolution and revolutionary practices marked something like the only possible point of convergence between life and politics, then biopolitical discourse, by taking their separation as its starting point, aims precisely to recompose them — to sublate their separation — but on a separate and transcendent plane. In doing so, it would have laid the epistemic foundations for a whole series of geopolitical, eco-political, and techno-political strategies aimed at reconciling human politics with life and its forms — perpetually deferring and reconfiguring what Giorgio Cesarano, fifty years ago, called "capital utopia": the advent of an apocalyptic recomposition of the contradiction between the human and its own life, and between the human and planetary life, under the sign of capital.18

In this regard, it is interesting to note that the most recent critical redefinitions of biopolitical discourse revolve precisely around this issue. On the one hand, Frédéric Neyrat has attempted to move beyond the "ecological repression" at the heart of Foucault’s biopolitical framework, formulating the hypothesis of a "biopolitics of catastrophe."19 According to Neyrat — who rereads key passages from The Will to Knowledge and Foucault’s lectures on The Birth of Biopolitics — Foucault linked the emergence of biopolitical power and its object (populations) to a loosening of death’s grip on life. Only when death no longer haunts life, so to speak, "from the outside" (through famines, epidemics, natural disasters, etc.), can life be taken in charge by politics — can it become the object of a management based on technologies of power. But in the Anthropocene, the daily proliferation of risks and catastrophes configures new ways in which life is exposed to death. As a result, forecasting and preventing catastrophes would now count among the essential techniques of governance.

Foucauldian biopolitical discourse should therefore be reformulated in terms of a decisive "ecological" expansion of the notion of "life" (a move that, as we have seen, would not have been unfamiliar to the Cahiers de la biopolitique) and, at the same time, it should be "temporalized" in a future-oriented, even apocalyptic, sense. With a slight shift in emphasis, one could say that biopolitics’ embrace of the environment inaugurates something like an apocalyptic governmentality, grounded in the administration of catastrophe.

On the other hand, Maurizio Lazzarato has repeatedly emphasized how Foucault’s framework — from the notion of "biopolitics" to that of "governmentality," from the category of "human capital" to the conception of power as diffuse and horizontal — has persistently obscured the resurgence of "processes of capitalist centralization, of transcendent unification and global consolidation," of vertical and monopolistic mechanisms of capitalist valorization, as well as authoritarian and repressive techniques of power.20 That is, biopolitical discourse has cast into its shadow both the fundamental categories of the Marxian critique of political economy and the key categories of the political itself: valorization and class struggle, capital and war, monopoly and revolution.21

Today, in the era of the biopolitics of catastrophe and apocalyptic capital, it is precisely these notions that are returning to the forefront. At a moment when, as Enzo Traverso writes, the idea of revolution has been completely obliterated from political and biopolitical discourse — a moment that has instead become associated with the imaginary of terrorism, social collapse, and, I would add, global catastrophe — a genealogical inquiry into the life-politics nexus could offer a crucial contribution to the recovery project outlined by Lazzarato.22

Life’s exhaustion

1968 is also the year of the founding of the Club of Rome, a think tank composed of heads of state, UN officials, diplomats, scientists, economists, entrepreneurs, futurists, and cyberneticists. Its explicitly "apolitical" program (having “absolutely no political ambition," according to former Club president Díez-Hochleitner) is dedicated to formulating methods to confront what, in a 1991 publication with the telling title The First Global Revolution, it calls "the world problematique": the heterogeneous and tangled set of "political, economic, cultural, psychological, technological, and environmental" issues that threaten humanity.23 At stake, then, is the development of a diversified, global, and long-term strategy aimed at managing the emergencies and crises proliferating in the "global world."

In 1972, the Club of Rome commissioned MIT to produce the now-famous report, The Limits to Growth. Translated into thirty languages, with 30 million copies sold, the report remained a constant reference point for government policies on ecological transition. Its predictions were grim: the exponential rate of planetary resource consumption, within a few decades, would lead to an irreversible halt in economic, industrial, and demographic growth on a global scale. Hence the need for a decisive reformulation of economic policies, which, by taking responsibility for the risk of both a biopolitical and ecological catastrophe, must devise strategies for transitioning toward "global equilibrium."

The following year, the poet, militant, and radical communist theorist Giorgio Cesarano, together with Gianni Collu, published Apocalisse e rivoluzione [Apocalypse and Revolution], a "situational text" that interpreted the MIT report not as the swan song of humanity, but of capital: a distorted fulfillment of Marx’s prognosis that capital, driven by its tendency toward expansion and the universalization of its self-valorization process, would inevitably collide with the limits of its own development. "Having completed its colonization of the thermodynamic system," capital would find itself with one last means of postponing its demise: reversing the trend, as the MIT report suggested.24

In the report’s conclusions, Cesarano thus foresaw the transition from a society of abundance — exemplified by Italy in the 1950s and 1960s — to a "society of famine,” based on an economy of debt (or, in Cesarano’s term, "fictitious capital"), governed by principles of austerity, and producing guilty subjectivities.25 The completion of capitalist globalization, the depletion of resources, and the exhaustion of material possibilities for value extraction will compel capital to shift the valorization process toward "immateriality," re-centering the value machine on credit capital. If the end of the gold standard, announced by Nixon in 1971, constituted the material basis of Cesarano’s argument, its obvious confirmation arrived shortly after the publication of Apocalypse and Revolution in the form of the 1973 oil crisis.

But the exhaustion of external, colonizable space would also mark the turn of capitalist colonization toward interiority — a shift that, as Lazzarato would later argue, is ultimately inherent in the functioning of the debt economy itself. It was in this way that global capital, as fictitious capital, reconfigured itself as an "infernal machine" capable of extracting value from life, from the psyche and, above all, from bodies. Whereas capital’s "formal domination" stopped at the threshold of political economy, the phase of "real domination" — i.e., the process that Cesarano, following Camatte, calls "the anthropomorphosis of capital" — is marked by the full subsumption of life and society into the process of self-valorization.26

By linking the fictitious production of "forms of life" to the new valorization techniques centered on "human capital," and pairing this with a theory of power exercised over bodies — thereby resolving the political problem into social command, i.e., into the imperative to produce and "defend society” — Cesarano thus anticipated, by a few years, the key points of Foucault’s analytic of biopower.27 With one crucial difference: in Cesarano, if power can take the form of biopower, this is only because capital’s self-valorization, after having produced a world-environment marked by catastrophe, seeks to capitalize on catastrophe itself, preempting its imminent future in the form of the neo-Christian society of induced scarcity. It is capital’s power which, in the 1970s, begins to structure itself as the apocalyptic governance of catastrophe.

Giorgio Cesarano and the biological revolution

Let us now return to the question we set out from: How did 1968 inaugurate an understanding of revolution as the site where life and politics coincide? It is precisely in Cesarano’s writings that the clearest answer to this question can be found. In Apocalypse and Revolution (1973) and, above all, in the unfinished (and posthumous) Critica dell'Utopia-Capitale [Critique of Capital-Utopia] (1993), the analytics of biopower and total capital correspond, on the dialectically positive side, to the radical idea of a "biological revolution."

"Life," writes Cesarano, "was still a ‘useful mystery’ as long as survival was a struggle between the species' body and the surrounding environment.”28 As long as the stakes of the "colonization of existence" were the survival of the species and of bodies against nature, life presented itself as infinite biodiversity, energy, or an inexhaustible resource and, in this sense, as a "mystery." This is the mystery in the face of which, according to Benjamin, the rule of juridical violence must come to a halt, so that "bare life" itself can continue to serve as the mute support of power and its mythical order.29 In the age of real domination, however, it is capital itself that takes charge of unveiling that arcanum imperii, life, by subsuming life as such into the value process.

In this way, Cesarano puts a decidedly biopolitical slant on Marx’s theory of value. "The logical key to production," Cesarano and Collu write, "lies entirely in the modification of the labor-survival relationship."30 If the "world of commodities" can function through the mechanism of exchange, it is only because the sale of labor-power has always been, first and foremost, an exchange of life-labor for mere survival.31 The real stake in this exchange is the expropriation of life, which coincides with the perpetual production of conditions for an unceasing intervention into the social body: the injection, into the body itself, of material negation (scarcity, as the impossibility of access to resources), psychosocial negation (lack, as the impossibility of pleasure), and temporal negation (delay, as the perpetual deferral of pleasure). As the management of survival, capital thus presents itself as the democratic "manager of death" for all and each.32 The decisive function of the capital machine is, in other words, something like a "thanatopolitical production": the production of a "society of the free market of survival."33

Yet, in penetrating the social body, capital simultaneously clears the ground of revolutionary theory of the mystifications of value. If, throughout the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, capital was able to overcome its contradictions by integrating the energy of bourgeois and proletarian revolutions as its own driving force, the era of real domination integrally abolishes politics as a separate sphere — the field of the seductions of representation. What is at stake, in short, is what I have characterized already (in reference to the slogans of 1968) as "the end of separation": the refusal of political delegation, the refusal to displace politics into a separate sphere, beyond the plane of immanence of living life.

For this reason, to "capitalist totalization," writes Cesarano,

…the real movement [responds] with the organic totalization of its radical revolt. […] The true content of the alternative at stake is apocalypse or revolution: this is what the body of the species now instinctively knows, ever since it became clear to everyone that it is no longer a matter of anything but finally living or ultimately dying. […] The revolution of life against death is a…biological revolution. [...] The liberation from imminent death coincides with the liberation of the species' body.”34

This entails an essential revision of Marx’s theory of the proletariat. For Cesarano, the identification of the proletariat — the essential instance of communism as the "real movement that abolishes the present state of things"35 — with the working class as an economic category internal to the mode of production, and with its political "vanguards," is nothing more than a phase of the real movement, now superseded. The proletariat was not “defeated,” as Trontian operaismo would claim; nor did it spread out across the entire “social field,” as Negri later argued; rather, it has been both disseminated and concentrated in the discrete punctuality of bodies.36

This is why, in the age of real domination, revolution can no longer take the form of an action dependent on a subject carrying revolutionary force. For the subject, here, is nothing more than a "social person," subjectivized capital and capitalized subject, the subjective organization of the valorization process. For Cesarano, the command of capital now declares: "Concentrate! You are the value."37

Once the subject has exited the field, the biological revolution, perfectly a-subjective, can take place in the simple body of the living: at the point where individual being and generic being, interior and exterior, everyday life and the life of the species, coincide. If biopolitical power can penetrate bodies, for Cesarano, the body itself, as the body of the species, remains essentially foreign to its grasp. Capital’s biopower can, in other words, only colonize bodies — but real dialectics erupts from their very center. In this sense, revolution cannot be understood as an action assignable to an agent, as an isolated moment in (pre-)historical time, or as a strategic program or project. Revolution is not, to put it in Benjaminian terms, the telos of historical dynamis, the intentional object of a revolutionary politics. Rather, it is a "state of the world," a mode of being. Outside the sphere of separate politics, revolution is now the very site of existence: the place where being and politics, finally, coincide. This is the meaning of Cesarano’s exhortation: "We’re down to the last drop — all that’s left is to be.”38

The fact that, under conditions of real subsumption, revolution — bypassing the subject, the project, and every form of political futurism — can appear only in perfectly a-subjective forms of bodily multiplicity, is precisely what the cycle of global uprisings over the past fifteen years has consistently demonstrated. The non-subject of biological revolution is, in fact, anyone whatsoever, quodlibet; and for this reason, revolutionary intensities can pass through any site, breaching the barriers of the social person. Following the killings of Eric Garner and (later) George Floyd, the utterance “I can’t breathe” did not so much become an intersubjective slogan of political composition, the genesis of a distinct political body, as it acted as an agent of intrasubjective contagion. As it passed through each singular ‘I’, “I can’t breathe” shattered the boundaries of the social persona, releasing within each individual the species’ body, the political life smothered by the apparatuses of capital valorization, on the immanent plane of a revolution without subject.

Likewise, during the Egyptian revolution of 2010, in the slogan, “We are all Khaled Said,” “Khaled Said” did not indicate the social person — the citizen oppressed by Mubarak’s authoritarian regime — but rather the disfigured body of Khaled himself, whose images spread across the web, once again unleashing the biological revolution.39 It is no coincidence that in both Paris and Milan, Nahel Merzouk and Ramy Elgaml were attempting to escape profiling operations — the fabrication of the social person — when they were killed by the police. And when the institutional left in Turin tried to mobilize Ramy’s name as a political watchword, organizing a march under the slogan “Ramy is alive and fights alongside us,” a girl’s voice, in tears, broke through the sound of the loudspeakers, crying out: “Ramy is dead! He was killed, and he cannot be here with us!” In the tears of that girl, once again, the corporeal shimmer of biological revolution comes to light. “There is nothing left to understand,” wrote Cesarano, “except that this is how one dies.”40

May 2025

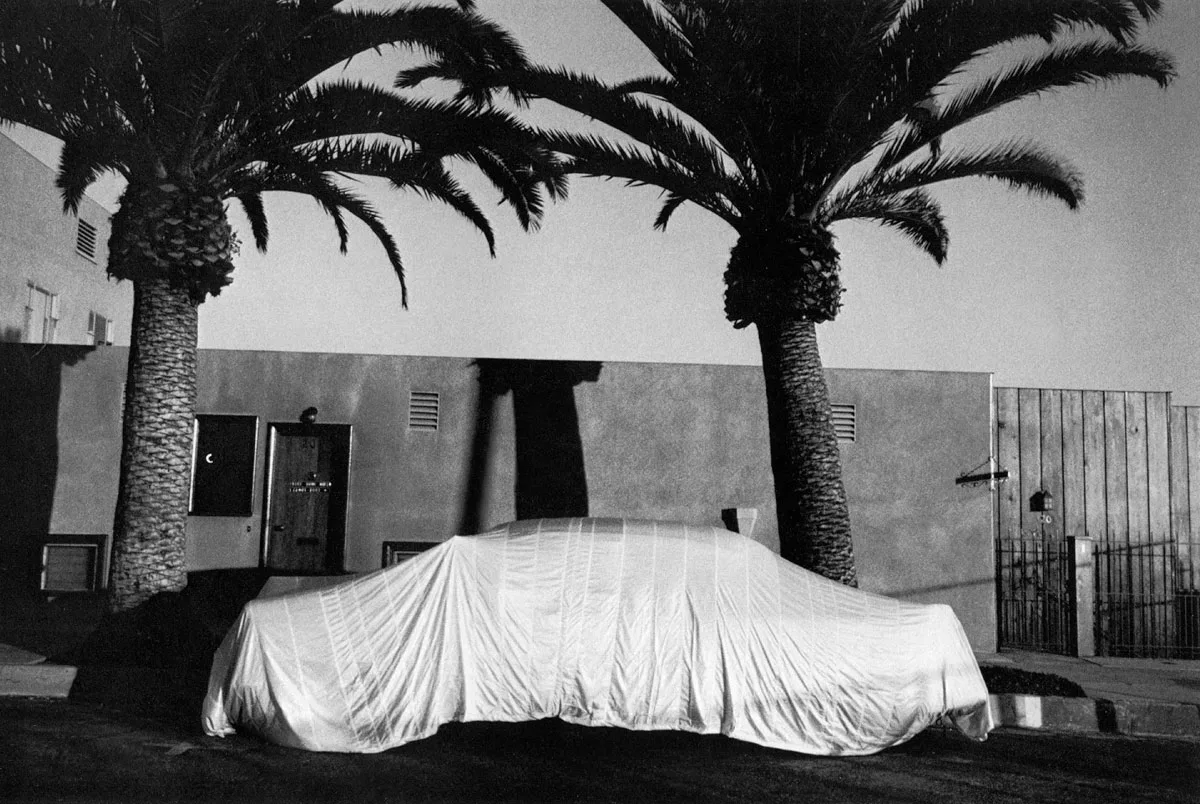

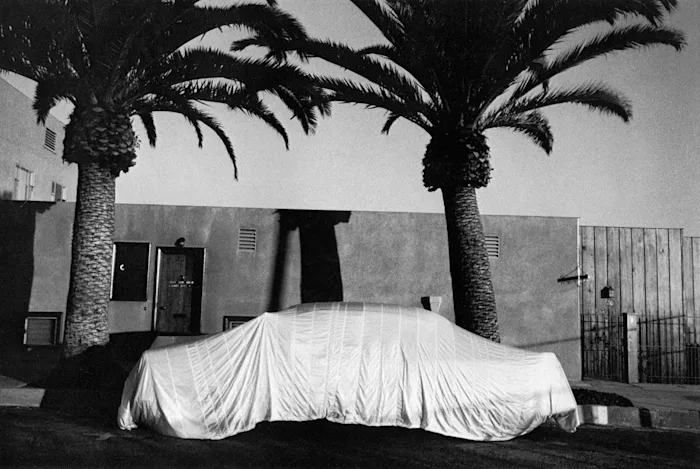

Images: Robert Frank

Notes

1. Alexander King and Bertrand Schneider, The First Global Revolution, a Report from the Council of the Club of Rome, Pantheon Books, 1991, ix. Online here.↰

2. Giorgio Cesarano and Gianni Collu, Apocalisse e rivoluzione [Apocalypse and Revolution], Dedalo, 1973, 67. (All quotations from Cesarano's works have been translated by the author).↰

3. Guy Debord, A Sick Planet, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith, Seagull Books, 93-94.↰

4. As observed in Sandro Chignola, “2000 d.c. Biopotere e biopolitica: sulle tracce della discussione,” Euronomade, June 13, 2016, fn. 1 (online here). On the history of the term “biopolitics,” see Thomas Lemke, Biopolitik. Zur Einführung, Junius Verlag, 2007.↰

5. Organization for the Contribution to Life (OSV), Cahiers de la biopolitique (1968); as cited in Tiqqun, This is Not a Program, trans. Joshua David Jordan, Semiotext(e), 2011, 111.↰

6. Organization for the Contribution to Life (OSV), Cahiers de la biopolitique (1968); cited in Tiqqun, This is Not a Program, 111. ↰

7. Critique de la séparation is the title of Guy Debord’s third film, released in 1961. The first chapter of The Society of the Spectacle is titled “Separation Perfected.”↰

8. Raoul Vaneigem, Basic Banalities (1963). Online here.↰

9. Jean-Philippe Legois, Les slogans de 68, First Editions, 2008.↰

10. Gilles Deleuze, “Immanence: A Life,” in Pure Immanence: Essays on a Life, trans. Anne Boyman, Zone Books, 2001. For an illuminating reading of Deleuze's essay, see Giorgio Agamben, "Absolute Immanence," in Potentialities: Collected Essays in Philosophy, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen, Stanford University Press, 1999, 220-239.↰

11. Walter Benjamin, “Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia,” trans. Edmund Jephcott. New Left Review, I/108, 1978, 47–56.↰

12. Jacques Camatte, “Mai-Juin 1968: le dévoillement,” Invariance, Serie III, n. 5-6, 1979, 2-10. Online here.↰

13. Camatte, “Mai-Juin 1968.” ↰

14. Raoul Vaneigem, The Revolution on Everyday Life, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith, Rebel Press, 2001, 26. Online here.↰

15. Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History,” in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, Donald F. Bouchard (eds.), trans. Donald F. Bouchard & Sherry Simon, Cornell University Press, 1977, 150.↰

16. On subjugated knowledge, see Michel Foucault, Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–1976, trans. David Macey, Picador, 2003, 7–10.↰

17. On the biopolitical turn and the discourses it has generated, see Timothy Campbell & Adam Sitze, “Introduction: Biopolitics: An Encounter,” in Biopolitics: A Reader, Duke University Press, 2013, 1–40.↰

18. Giorgio Cesarano, Critica dell'utopia capitale, in Opere complete, Vol. 3, edited by Centro di iniziativa Luca Rossi, Colibrì Edizioni, 2019. For a potent historical, political, and theoretical framing of Cesarano’s thought and of radical communism in Italy, see Francesco "Kukki" Santini, “Apocalypse and Survival” (1994). Online here.↰

19. Frédéric Neyrat, "The Biopolitics of Catastrophe, or How to Avert the Past and Regulate the Future," South Atlantic Quarterly 115:2, 2016, 247–265.↰

20. Maurizio Lazzarato, “The Impasses of Western Critical Thought,” trans. Eric Aldieri, Ill Will, April 22nd, 2025. Online here.↰

21. Lazzarato, Governing by Debt, trans. Joshua David Jordan, Semiotext(e), 2015, 1–10.↰

22. Enzo Traverso, Revolution: An Intellectual History, Verso, 2021.↰

23. Alexander King & Bertrand Schneider, The First Global Revolution, a report from The Club of Rome, Pantheon Books, 1991, x. Online here.↰

24. Giorgio Cesarano & Gianni Collu, Apocalisse e rivoluzione, 67.↰

25. Giorgio Cesarano, Piero Coppo & Joe Fallisi, “Cronache di un ballo mascherato” [“Chronicle of a Masked Ball”], edited by Archivio Anomia. Online here. ↰

26. On the concepts of capital’s anthropomorphosis, real domination, and value-in-process, see Jacques Camatte, Capital and Community: The Results of the Immediate Process of Production and the Economic Work of Marx, trans. David Brown, Unpopular Books, 1988. On the deep political and theoretical bond between Camatte and Cesarano, see the insightful testimony of Camatte, Con Giorgio Cesarano, online here.↰

27. Michel Foucault, Society Must Be Defended, 239–242.↰

28. Giorgio Cesarano & Gianni Collu, Apocalisse e rivoluzione, 64.↰

29. Walter Benjamin, "Critique of Violence," in Selected Writings, Volume 1: 1913–1926, ed. Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings, Harvard University Press, 1996, 250: “For with bare life, the rule of law over the living ceases” (translation modified).↰

30. Giorgio Cesarano & Gianni Collu, Apocalisse e rivoluzione, 58.↰

31. On this point, Cesarano seems to anticipate Paolo Virno's insightful integration of Foucault and Marx, biopolitics and value, in A Grammar of the Multitude: For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life, trans. Isabella Bertoletti, James Cascaito, and Andrea Casson, Semiotext(e), 2004, 81–82.↰

32. Giorgio Cesarano & Gianni Collu, Apocalisse e rivoluzione, 108. ↰

33. Giorgio Cesarano & Gianni Collu, Apocalisse e rivoluzione, 62.↰

34. Giorgio Cesarano & Gianni Collu, Apocalisse e rivoluzione, 87.↰

35. Karl Marx, “Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law. Introduction,” in Karl Marx: Early Writings, trans. Rodney Livingstone & Gregor Benton, Penguin Classics, 1992, 244–245. It is Marx's famous dictum, to which what Bordiga called the "historical party" has referred in each of its manifestations: “Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things.”↰

36. It can indeed be argued that the debate on “affirmative” biopolitics within Italian Theory has developed — quite literally — in the shadow of Cesarano’s discourse; that is to say, as its inverse and opposite. A notable exception to this trend is Giorgio Agamben’s critique of biopolitics. The line of development stemming from operaismo, which Negri would later term “worker self-valorization,” is precisely what leads Bordiga, Camatte, and Cesarano to separate proletarian force from the working class. See, for example, Mario Tronti, “Our Operaismo,” New Left Review, n. 73, January–February 2012, 119–139 (online here); and Michael Hardt & Antonio Negri, Empire, Harvard University Press, 2000, 29-32.↰

37. Giorgio Cesarano & Gianni Collu, Apocalisse e rivoluzione, 101.↰

38. Giorgio Cesarano & Gianni Collu, Apocalisse e rivoluzione, 140.↰

39. Cf. The Invisible Committee, To Our Friends, trans. Robert Hurley, Semiotext(e), 2015, 48, 53, where a declaration issued by several Tahrir Square insurgents is cited: "In Egypt, we didn't make the revolution in the street just for the purpose of having a parliament. Our struggle […] is broader in scope than the acquisition of a well-oiled parliamentary democracy."↰

40. Giorgio Cesarano & Gianni Collu, Apocalisse e rivoluzione, 87.↰