The United States and “Fascistic Capitalism”

Maurizio Lazzarato

Continuing the reflections begun in "Why War?," "Political Conditions of a New World Order," and "The Impasses of Western Critical Thought," philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato argues that the shape of the next phase of history will not be determined economically, like an exchange between contractors, but only by forces capable of entering the strategic plane of the friend-enemy relation. To clarify the stakes of this decision, the present article returns to the bloody process through which neoliberalism was “imposed” globally, especially in Latin America, which exceeds any superficial opposition between democracy and fascism.

Other languages: Español, Français, Ελληνικά

Primitive accumulation, capital’s state of nature, is the prototype for capitalist crisis. —Hans Jürgen Krahl

Capitalism isn’t reducible to a cycle of accumulation, for it is always preceded, accompanied, and followed by a strategic cycle defined by conflict, war, civil war, and, when necessary, revolution. This strategic cycle includes the so-called “primitive accumulation” described by Marx, but only as its first phase, followed by the exercise of violence embodied in “production” and the outbreak thereof into war and civil war upon the exhaustion of the economic cycle. For a complete description of the strategic cycle, we had to wait until the 20th century and its transformation into the cycle of Soviet and Chinese revolutions — a transformation that, from different viewpoints, corrects and completes Marx.

The two cycles work together. Their dynamics are intertwined, but can also be separated from one another: since 2008, the cycle of conflict, war, and civil war (and the improbable possibility of revolution) has been gradually separating itself from the cycle of accumulation in its proper sense. The deadlocks and impasses in the accumulation of capital require the intervention of the strategic cycle, which functions on the basis of force relations and the non-economic friend-enemy relation.

Ever since the advent of imperialism, the importance of the strategic cycle has only heightened. Cycles of war, of tremendous violence, and of the arbitrary use of force rapidly succeed one another. The USA has thrice imposed economic and juridical rules on the world market and World Order (1945, 1971, and 1991), and thrice it has erased or modified the norms that it had imposed because those norms were no longer convenient for them and instituted new ones. The Fordism of 1945 was dismantled in the 1970s, while the so-called “neoliberalism” that was chosen to replace it, and which was spread across the entire world in 1991 after the fall of the Soviet Union, collapsed in 2008. Today’s primitive accumulation is once again changing the rules of the game for the sake of a more-than-improbable attempt to “Make America Great Again.”

The analysis of the strategic cycle in contemporary capitalism must bear first and foremost on the United States, for it is there that its apparatuses of power are concentrated — the military, financial, and monetary institutions over which it holds monopolies forbidden to “allied” Europe or East Asia, i.e., countries subjugated either by war (Germany, Japan, Italy) or by economic and financial power (France, the UK) and, most importantly, to the global “South.”

Since the 2008 crisis, the strategic cycle has come to the forefront, to the point even of supplanting the “market,” economic regulations, international law, diplomatic relations between states, etc., all while aiming to stave off the implosion of the cycle of accumulation and revitalize the US economy, which is in serious trouble.

We have the “luck” of being able to watch this primitive accumulation and strategic cycle unfold live. Trump has triggered the “state of exception.” But this state is quite different from the one canonically defined by Carl Schmitt or taken up by Giorgio Agamben. Instead of being concerned with “public law” and the formal constitution of the Nation State, it is first and foremost aimed at the rules of the material constitution of the global market and the international legal norms of the world order. With the global state of exception, the space wherein the nomos of the earth takes shape, with its lines of amity and hostility, is global civil war. Instead of focusing on law, the global state of exception deeply integrates economics, politics, the military, and the juridical system.

Global civil war reverberates back upon domestic civil war by intensifying racism and sexism, the militarization of territory, the deportation of immigrants, attacks on universities, museums, etc. The population of the United States is deeply divided — not between the 99& and the 1%, but between the 20% who ensure the bulk of consumption within the enormous domestic market (3/4 of GDP) and the 80% whose consumption is either stagnating or declining. Fiscal policies are being implemented to guarantee the property and hyper-consumption of the wealthiest part of the population.

Trump has the merit of politicizing what so-called neoliberalism was so intent on depoliticizing without being able to. Once all rules are suspended, the use of extra-economic force becomes the precondition for economic production, the establishment of law, and the constitution of any institution whatsoever. It is first necessary to forcefully impose power relations. Then, once the division between those who command and those who obey has been established (and the situation stabilizes because it is accepted by those who have been subjugated), one can reconstruct economic and juridical norms, the automatisms of the economy, national and international institutions, the expression of a new “order.”

The strategic cycle working through the “global state of exception” was ensured by arbitrary and unilateral political decisions made by the American administration, whose aim is to impose a series of “takeovers” (appropriations, expropriations, plunders1) of other people’s wealth — directly extorted, with neither mediation nor industrial exploitation, nor the predation enacted via debt and financialization.

What is the meaning of this long (and here partial) list of political decisions made on the basis of the coercive power of the imperial state? The change in “economic” relations is not immanent to production. Nor is it the result of the “laws” of finance, industry, or trade established by economic theory.

The economic “automatisms” politically imposed across the 1970s and ’80s by the United States can only reproduce the ends for which they had been politically instituted (financialization, the debt economy, industrial delocalization, etc.) and thus reproduce the crisis. These apparatuses do not have the capacity to innovate — either by distributing power differently, or by producing new relations between states and classes, which would then serve as the conditions for a “new” form of production. The configuration of powers we are examining demands a break. It is not deducible from the situation that has led to this crisis. It requires a leap out of the situation. The leap must be thought and organized by a “new” dominant class, one that subjectivizes the break, occupying the state and using it strategically.

The administration assumes the role and function of the strategist, of the warlord who decides, on the basis of the friend-enemy relation, and no longer on the “equality” of exchange between contractors, who should pay and how much should be paid for the crisis of the United States.

In order to understand the “politics” of the United States, which has managed, for a while now, these phases of primitive accumulation, we must neither oppose it to “economics,” nor reduce it to the political class as a whole. It constitutes the coordination of various centers of power (administrative, financial, military, monetary, industrial, media-based) provided with a strategy. The heterogenous interests that characterize them find a certain mediation in the need to fight against a “common enemy” — the rest of the world, but first and foremost BRICS, and Russia and China in particular. The Trump administration assumes the function of collective capitalist, of the leader capable of negotiating a strategy with other financial, military, and monetary powers that would continue to act according to their own interests, albeit interests that must ultimately converge — for what is at stake is not the health of the American economy, but the possibility of the collapse of the economic-political machine of financial capitalism and debt, a machine that is on its last legs.

Economic intimidation and blackmail, the intimidation and blackmail of military intervention, wars, and genocide, are all being mobilized at the same time. The United States is threatening to intervene in “its backyard” (Latin America) under the pretext of narco-trafficking in Colombia, Mexico, Haiti, and El Salvador, whilst directing guns at Venezuela. They have beckoned the region’s ministers of defense to Buenos Aires (19/21 of August) to demand a seamless alignment against China and impose a strengthening of American military presence in the “straits” (Magellan, Panama, etc.) “which could be utilized by the Chinese Communist Party to extend its power, disrupt trade, and defy the sovereignty of our nations and neutrality of Antarctica.”

In contemporary conditions, it is difficult to even speak of capitalism, of a “mode of production,” for we are confronted with the action of a “lord” who is arbitrarily deciding upon the quantity of wealth that he is entitled to extract from the production of his “serfs.” The American Secretary of the Treasury, Scott Bessent, has declared without a shred of embarrassment that the United States would treat the wealth of its “allies” as if it such wealth were its own: Japan, South Korea, the United Arab Emirates, and above all, Europe, have committed themselves to investing “according to the wishes of the President.” This is a matter of “a sovereign wealth fund, managed at the discretion of the President, in order to finance a new industrialization.” The host of Fox News, stupefied, describes it as an “offshore appropriation fund.” Bessent: “Oh, it’s an American sovereign wealth fund, but with other people’s money.”

The impersonal relations of the market are becoming personal again by opposing “the master and his slaves,” the colonizer and the colonized. It is not commodity fetishism — it is not the automatism of currency, of the market, of debt, etc. — that rule and decide, but force, the expression of a political will. The United States no longer designates the competitor, but the enemy — an enemy it has now identified as the rest of world, including its allies (in fact, primarily allies insofar as they are part of the same dominant class and are terrified by the idea of the collapse of the center of the system, which would also lead to their own downfall; to save capitalism, they are ready to strip their populations bare, particularly Europe which, like Japan in the 1980s, will be forced to pay for the United States’ crisis, sacrificing its economy and its working classes while exposing itself to the risks of civil war).

The law of value or of marginal utility — i.e., all the categories of classical or neoclassical economics — are completely useless. They explain nothing about what is currently happening. Instead of all too complicated econometric models, all one needs is a mathematical operation learned in primary school to calculate the tariffs being applied to the rest of the world. The so-called complexity of contemporary societies dissolves quite easily in the face of the friend-enemy political duality. “Creative destruction” is not the prerogative of the entrepreneur, but the work of political, economic, and military decision makers.

Not even Karl Marx’s Capital (at least beginning with primitive accumulation instead of the commodity) is very useful when it comes to explaining the situation. Pierre Clastres, whose reading of Nietzsche, focusing on the will to power, is very different from Foucault’s, can give us some food for thought: economic relations are power relations that can never be separated from war. His description of how “power” works when it affirms itself at the expense of very early “societies against the state” is still the most fitting commentary that I have read on the current operation of the state/capital machine that is the United States administration.

The economic order, that is to say, the division of society into rich and poor, exploiters and exploited, is the result of a more fundamental division of society: the division between those who rule and those who obey, between those who maintain power and those who are subjected to it. It is thus essential to understand when and how the relation of power, of rule and obedience, is born in society. In what manner do those who hold power become exploiters, and how do those who are subjected to it or recognize it — the difference matters little — become exploited? The point of departure, quite simply, is tribute. It is fundamental. We must never forget that power only exists in its own exercise: a power that is not exercised is not power. The sign of power, the sign that it really exists, is, for those who recognize it, the obligation to pay a tribute. The essence of a power relation is a relation of debt. When society is divided between those who rule and those who obey, the first act of those who rule is to tell the others: “We rule, and we can prove it to you by demanding you to pay a tribute.”2

We can easily interpret the relation between ruling and obeying as determined by the violence of primitive accumulation that is constantly repeated, and the relation between exploiter and exploited as the exercise of power in “production” once “order” has been established and the situation “normalized”: both relations (ruling/obeying and exploiter/exploited) are complementary actions of the same state-capital machine. Clastres’ critique of “economics,” determining even “politics” in the last instance, seems pertinent to us, so long as we consider the will to power and the will to accumulation as two sides of the same coin.

The tribute to be paid to the United States administration should be the sign of a new redistribution of power — one capable of drawing up a new “nomos of the earth,” that is, a relation of colonial subordination of allies to the US, on the one hand, and the more difficult operation of BRICS to the US, on the other. Internal to each State, tribute should be recognized as the sign of the submission of the dominant classes, who are supposed to be the real payers. Trump’s arrogance hides his weakness: wanting to impose a new world order while overseeing the defeat of NATO in Ukraine, a monstrous economic crisis, and a global south that is not submitting as easily as Europe did.

The new order can only be established by imperialism, characterized since its inception by the complementarity of economics and politics, war and production. The collective imperialism defined by Samir Amin in the 1970s, wherein the central role was reserved for the United States, has been transformed into a real colonial subordination of allies: Europe, South Korea, Japan, Canada, etc. Europe is in the same condition of colonial subordination that England once imposed upon India in the 19th century, for like the latter, it must pay a tribute to the “occupying” country, building and financing European armies, with resources bought from the US in order to wage war against enemies defined by the imperial power (the war in Ukraine is the experiment, a general test for this kind of war).

“Neoliberalism” and the reversibility of fascism and capitalism

The new sequence of the strategic cycle, which began in 2008, leading to open war, bears a tremendous novelty. The state-capital machine no longer delegates tremendous violence to fascists. Instead, it organizes such violence itself — still feeling burned, perhaps, by the autonomy that Nazism took on in the first half of the 20th century. The genocide sheds a disturbing light on the nature of both capitalism and democracy, forcing us to see them as we have perhaps never seen them before.

Capitalism and democracies are both together and in their own right orchestrating a genocide as if it were the most normal and natural thing in the world. Numerous companies (logistics, weapons, communications, control, etc.) economically participated in the occupation of Palestine and are now orchestrating, with absolutely no qualms, the economy of genocide. Like German companies in the 1930s and 40s, they are promising massive profits from the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. The main index of the Tel Aviv stock exchange rose 200% over the course of the genocide, ensuring the continuous flow of capital, mostly Americana and European, to Israel.

With the genocide, liberal democracies have reconnected with their genealogies which, once happily repressed, now return with a vengeance. The United States built its foundations on the genocide of Native Americans and the institutions of racism and slavery, while European democracies did much the same, albeit in far-off colonies. The colonial question, the questions of racism and slavery, lie at the heart of the two liberal revolutions toward the end of the 18th century.

The structural racism that characterizes capitalism and is today concentrated against Muslims was shamelessly unleashed by the Israelis, the entire Western media, and all Western political classes. Here, too, without much of a need for any new fascists, because it is states, particularly European ones, that have fueled it since the 1980s (while in the United States, it is endemic and central to the exercise of power). Racism has been deeply rooted in democracy and capitalism since the conquest of the Americas, for in them, inequality reigns, and one of the central ways of legitimatizing said inequality is through racism.

The debate over contemporary fascisms is occurring all too late, for none of these “new fascisms” is capable of exercising such violence and promoting destruction at this scale. For various reasons, they are not like their ancestors, which were charged with conducting a massive counter-revolution against socialism. The main reason, however, is the following one: there is no real enemy even remotely resembling that of the Bolsheviks. Contemporary political movements constitute no threat whatsoever. They are entirely harmless.

The new fascisms are marginal in relation to historical fascisms, and when they come to power, they place themselves immediately on the side of capital and the state by limiting themselves to intensifying authoritarian/repressive legislation and influencing the symbolic and cultural spheres. This is what Italian fascists are in the process of doing.

Trump (or Milei) is the perfect image of the “fascistic capitalist” because he represents a portion of the capitalist class and acts as such. Trump’s actions have nothing to do with historical fascist folklore, except perhaps marginally, when he acts at the geopolitical level in order to save American capitalism from imploding all while imposing a fascist becoming of every aspect of American society.

Capitalism has no need to delegate power, as it did in the past, to fascisms, for democracy has been emptied out from the inside since the 1970s (see the Trilateral Commission). It produces, from within its very own institutions — like capitalism does from within finance and the state does from within its own administration and military — war, civil war, and genocide. What we call “new fascisms” or “post-fascism” are but actors playing minor roles. They have no choice but to accept the decisions made by financial, military, monetary, and state-based centers of power.

How are we to understand this unprecedented situation? It has deep roots in the previous phase of primitive accumulation that organized the transition from Fordism to so-called “neoliberalism.” The strategic cycle organized by the Nixon administration to make the rest of the world pay, like today, for the accumulated crises of the 1960s was as of yet more violent than Trump’s actions: a unilateral decision to make the US dollar inconvertible into gold3, 10% tariffs, Japanese capital made available to the United States, the Plaza “Accord” that plundered Japan and at the time China, sacrificing the latter’s economy in order to save American capitalism; the reestablishment of political relations with China that would prove decisive for globalization; the political decision to construct a “super-imperialism” around the dollar, and so on.

Some of the most dramatic episodes of this strategic cycle were the civil wars all over Latin America which simultaneously declared the end of the global revolution and initiated the first so-called neoliberal experiments. In this regard, it is interesting to revisit Paul Samuelson’s “Nobel Prize” winning economic analysis of nascent neoliberalism, for it is almost never recalled.

We have considered Foucault’s analysis of the “Birth of Biopolitics” to be an impressive anticipation of neoliberalism, even though during the same era Paul Samuelson’s interpretation admirably cut straight through the admiration of the market, freedoms, tolerance of minorities, governmentality, etc., by describing the neoliberal economy as a “fascistic capitalism,” in the sense that, with the neoliberal market, the two terms become reversible. This category, forgotten in the years that followed, will perhaps help us understand the genealogy of democratic-capitalist genocide.

What I am alluding to is of course the fascist solution. If the efficient market is politically unstable, then fascist sympathizers conclude: “Get rid of democracy and impose upon society the market regime. Never mind that trade unions must be emasculated and pesky intellectuals put into jail or exile.”4

The “market” (read: “capital,” which is not the same thing) has since the 1970s gradually destroyed the democracy of the post-war years, the only one that could even somewhat resemble its own concept since it arose from the global civil wars against Nazism. Once this political energy was exhausted, fascistic capitalism began to institute itself. The logic of the market, instead of being an alternative to war and terrific violence, contained them, fueled them, and ultimately practiced them itself — even to the point of genocide. In the era of monopolies, the market — that supposedly automatic form of mediation — constitutes, in reality, the end of all mediation, for it makes force emerge as the decisive actor: the force of monopolies, the force of finance, the force of the state, and so on. Not only must there be civil war to establish it, but it also delegates the functioning of capitalism to force. In this sense, the market is already a fascist economy.

Samuelson turns the most solid of belief systems on its head: the economy of the Chicago Boys — Hayek, Friedman, etc. — is a form of fascism and constitutes a paradigm for the economy in general. The neoliberal experiment is that of an “imposed economy,” which is precisely what the Trump administration is trying to realize: an “imposed capitalism” (another one of Samuelson’s felicitous terms), a capitalism imposed by force.

The 1980 Eleventh Edition of my Economics has a new section devoted to the distasteful subject of capitalist fascism. So to speak, if Chile and the Chicago boys had not existed, we should have had to invent them as a paradigm. It is relevant to quote some of my words — the more so because conservatives who dislike how democracy works out are unwilling to follow their logic to the fascist conclusion these days and use constitutional limits on taxation as their form of imposed capitalism. Here are the words to describe fascistic capitalism...5

We have accepted the liberal narrative, rather than asking ourselves why governance is leading to war, fascism, and genocide just like it did in the first half of the 20th century. We ourselves have not been able to draw the necessary conclusions, and yet we have passed from the so-called freedoms of neoliberalism to democratic-capitalist genocide without a coup d’état, without a “march on Rome,” without a mass counter-revolution, but as if it were a natural evolution. Not a single person from the establishment, least of all the political and pundit classes, have been bothered by this. Quite to the contrary, the latter have aligned themselves with astonishing haste around a narrative that contradicts, from top to bottom, the decades-long professed ideology of human rights, international law, democracy against dictatorship, etc. For all of this to have occurred without the slightest hiccup, the physical and media horrors of the genocide had to have been inscribed into the structures of the system which, once the horrors emerged, considered them not as an aberration, but as a normality. All of this unfolded as if it were a matter of course. “Liberal” capitalism has, quite naturally, fully expressed and realized itself in genocide without fascist mediation, without fascists constituting an “autonomous” political force like they did in the 1920s.

We’ve failed to see what’s been lying right before our eyes because we have put on too many “democratic” filters — a pacified idea of capitalism that prevents us from accurately reading what happened with the construction of neoliberalism in Latin America. Let’s read Samuelson again, keeping in mind all the commentaries of critical thinkers who continue, even after 2008, to speak of neoliberalism:

Generals and admirals take power. They wipe out their leftist predecessors, exile opponents, jail dissident intellectuals, curb the trade-unions, and control the press and all political activity. But, in this variant of market fascism, the military leaders stay out of the economy. They don't plan and don't take bribes. They turn over all economics to religious zealots — zealots whose religion is the laissez faire market, zealots who also take no bribes. (Opponents of the Chilean regime somewhat unfairly called this group “the Chicago Boys,” in recognition that many of them had been trained or influenced by University of Chicago economists who favored free markets.) Then the clock of history is turned back. The market is set free, and the money supply is strictly controlled. Without welfare transfer payments, workers must work or starve. Those unemployed now hold down the growth of the competitive wage rate. Inflation may well be reduced if not wiped out.6

In reality, the function of the “fascist” market was never economic. It was, above all, repressive of the individualization of the proletariat and of any collective or solidaristic action and, secondarily, disciplinary. The market has been an immanent ideological construct under whose cloak predation could calmly proceed, a predation made possible by the monopoly of the “dollar” and “finance” as well as United States military violence, the real economic-political agents of neoliberalism that have never been regulated nor governed by the market.

Where can we confirm the pertinence of Samuelson’s concept that implies the oxymoron, “fascist democracy”? We have trouble grasping reality because the tremendous violence that combines democracy and capitalism conceals, with disconcerting ease, the values of the West, enshrined in its constitutions. The young Marx reminds us that the heart of liberal constitutions is neither freedom nor equality nor fraternity, but bourgeois private property. This is an incontestable truth, all the more so because it is “the most sacred right of man” affirmed by the French revolution — the only real value of the capitalist West.

Property is certainly the most pertinent way to define the situation of the oppressed. The primitive accumulation enacted by Nixon in the 1970s politically imposed an initial appropriation and distribution, establishing a proprietary division unprecedented in Marx’s time: this new division was not primarily between capitalists, owners of the means of production, and workers, deprived of any property, but between the owners of stocks and bonds, that is, between holders of financial securities and those that hold none of them. This “economy” functions like Trump’s tariffs, extracting wealth from the society of “serfs” with the only difference being that predation proceeds by the “automatisms” of finance and debt, automatisms that are continuously and politically maintained.

Society is divided more than ever: at the top are concentrated the owners of equity/securities, below the vast majority of the population who, in reality, is no longer composed of political subjects but of the “excluded.” As was the case for serfs of the ancien régime, economic “function” does not entail political recognition. The integration of the workers’ movement, which was recognized as a political actor for the economy and for democracy in the years following the war, has reverted into the exclusion of the working classes from any instance of political decision-making. Financialization has allowed those at the “top” to practice secession. It organizes its relationship with the lower classes to be one exclusively of exploration and domination. The serfs have not just been expropriated economically, but have also been deprived of any political identity such that they have adopted the culture/identity of the enemy — individualism, consumption, the ethos of television and advertising. Today they are driven to assume a fascist identity and a wartime subjectivity.

The “serfs” are fragmented, dispersed, individualized, divided in a thousand ways (by gender, race, income, wealth) — but all are participating, to varying degrees, in the segregated society established by the state-capital machine, a machine that no longer needs any legitimation, so favorable are the current power relations to it. Decisions are being made about genocide, rearmament, war, and economic policies without anyone having to answer to their subordinates. Consent is no longer necessary because the proletariat is too weak to even claim to count for anything. It is clear that in this situation, democracy is meaningless. The condition of the oppressed more closely resembles the situation of the colonized (a generalized colonization) rather than that of a “citizen.”

Walter Benjamin warned us: “The current amazement that the things we are experiencing are ‘still’ possible in the twentieth century is not philosophical. This amazement is not the beginning of knowledge — unless it is the knowledge that the view of history which gives rise to it is untenable.”7

What is additionally untenable is a certain idea of capitalism held even by the economism of Western Marxism. Lenin defined imperialist capitalism as reactionary, unlike competitive capitalism, in which Marx still saw some “progressive” aspects. Financialization and the debt economy have created a monster, fusing capitalism, democracy, and fascism and posing absolutely no problem to the dominant classes. We should be investigating the nature of the enemy’s strategic cycle, declaring for ourselves a single goal — to transform it into a strategic cycle of revolution.

Translated by Eric Aldieri

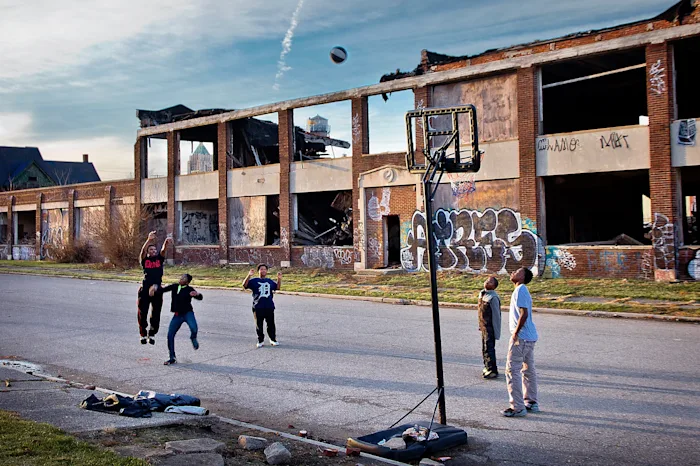

Images: Vincent Peal

Notes

1. Tariffs range between 15% and 50%. A reduction in the tax rate was promised on the conditions of (1) purchasing securities from the American market that are having trouble among buyers on the markets and (2) the free transfer of billions of dollars to the USA. -Tariffs serve a twofold purpose: one economic (the US needs fresh money in order to cover its deficits), the other political (India trades freely with Russia, etc., and Brazil “persecuted” Bolsonaro). -Impositions of US energy purchases four times dearer than market price: Europe has promised to -An obligation to invest billions of dollars in American reindustrialization (Japan, Europe, South Korea, the UAE have promised astronomical sums, with Europe’s $600 billion considered as a “gift” by Trump). Investments that will be at the discretion of the United States, under threat of an increase in tariffs. -The GENIUS Act authorizes banks to hold stablecoins as reserve currency in order to cope with the difficulties involved in placing the enormous public debt securities. The political condition for these stablecoins is that they be indexed to the dollar and used for the purchase of US debt.↰

2. R. Bellour and P. Clastres, “Entretien avec Pierre Clastres,” in R. Bellour, Le livres des autres. Entretiens avec M. Foucault, C. Lévi-Strauss, R. Barthes, P. Francastel, Union générale d’éditions, 1978, 425-442. [We were not able to find a corresponding English translation. —trans.]↰

3. [While the United States first went off the gold standard by executive order in April 1933, it wasn’t until August, 1971 that Nixon ended the ability of foreign governments to exchange dollars for gold. —trans.]↰

4. Paul A Samuelson, “The World Economy at Century’s End,” Human Resources, Employment and Development. Vol 1, the Issues: Proceedings of the Sixth World Congress of the International Economic Association held in Mexico city, 1980, ed. Shigeto Tsuru, Palgrave International Economic Association Series, 1, 1983, 75. ↰

5. Samuelson, “The World Economy,” 75. [In the French from which Lazzarato is quoting, “capitalisme imposé” resonates with the word for taxation, i.e., “l’imposition.” —trans.]↰

6. Samuelson, “The World Economy,” 75. ↰

7. Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” trans. Harry Zohn, Selected Writings Vol. IV, 1938-1940, Harvard, 2006, 392. ↰