Revolts Without Revolution

Adrian Wohlleben

The following article is based on a public talk delivered on October 3rd, 2025 in Montréal, Quebec. It served as the inaugural event of Octobre, a month-long series of discussions concerning the prospects for revolution in our present.

Other languages: Español, Italiano, Français, Português

I. The era of revolts is unfinished.

Those in search of a revolutionary science of the present should prepare for disappointment. There is no single compass by which to navigate our stormy seas, no skeleton key or magic formula that can right our ship and set us unequivocally on the path to revolution. The darkness of our horizon is deeper than any we have known in our lifetimes.

Still — while those living in North America might be forgiven for thinking so — there is no absence of movement: when we cast our gaze widely, taking in our global situation, we find waves stirring and breaking at such a dizzying pace that it is impossible to keep apace of them all, even for those of us who make a practice of it.

The past six months alone have seen mass unrest and uprisings in Turkey, Argentina, Serbia, Kenya, Indonesia, Nepal, the Philippines, and Peru. Before these: Bangladesh, Georgia, Nigeria, Bolivia…and this list is surely incomplete. In each case, mobilizations drawing tens of thousands or more led to escalating clashes with the forces of order across multiple cities, triggering national security crises. Just this month, the president of Madagascar dissolved the government in response to three days of deadly protests led by "Gen Z" over cuts to water and power and political corruption, sporting the same pirate-themed One Piece flag as those in Indonesia and Nepal.1 As I write this, a new uprising is breaking out in Morocco, as mass demonstrations in eleven cities morph into ferocious riots and clashes. To these must be added earlier sequences that remain ongoing, such as the civil war in Myanmar, where insurgents continue to make advances, seizing entire cities from the Junta.

In sum, although the global COVID-19 pandemic appeared to some theorists as a nefariously-designed plot to quash the concussive wave of revolts that circled the globe between 2018-19, as Americans discovered as early as May 2020, such fears were fortunately misplaced. In spite of a brief slowdown from 2021-23, the past year and a half has confirmed that the new “era of riots”2 (as the Greek communist group Blaumachen described it in 2011) is far from over.

Reflection’s task here is twofold: to situate these revolts within the epochal ruptures to which they attest, and to identify their undeveloped potencies by tracing the rifts between the practices that populate them.

II. The neoliberal world order is coming to an end, yet a new regime has not yet replaced it. All parties have been pushed onto a strategic plane.

While there is great chaos under heaven, it can hardly be said that the situation is excellent.

We are living through an interregnum. For nearly two decades, the global neoliberal order of financial capitalism that installed itself in the 1980s, and later spread across the globe in the 1990s, has been afflicted by persistent and mounting crises of profitability. Political parties unable to secure economic growth through market means alone are confronted with a choice: either be defeated in the next election cycle by opponents who will promise growth, only to likewise fail to deliver it, or secure profits through extra-economic strategies reliant on war, looting, conquest, and dispossession. For this reason, since the financial crisis of 2008, the accumulation cycle can no longer operate solely through its own immanent rules and systems, hierarchies, and values, for its “deadlocks and impasses….require the intervention of [a] strategic cycle, which functions on the basis of force relations and the non-economic friend-enemy relation.”3

For example, what is Trump’s plan for “derisking the US economy” through reindustrialization? Through a combination of economic and military threats (tariffs for some, invasions for others), the aim is to coerce countries allied with the US into investing in stateside factories. As Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent explained in a Fox News interview in August4, in exchange for the “easing of some tariffs for foreign allies,” Japan, South Korea, United Arab Emirates and other European nations “will invest in companies and industries that we direct — largely at the President’s discretion. Other countries, in essence, are providing us with a sovereign wealth fund.” As the Fox News correspondent summed it up, “The President loves new factories [...] And if a couple of these countries have to pay up for the privilege of helping us — fine.” In other words, American growth and stability will be purchased directly through economic intimidation and military blackmail.

III. Contemporary uprisings and neoauthoritarianism are both symptoms of the collapse of neoliberal capitalism.

It is against this backdrop that we must situate not only the wave of global uprisings initiated by the movement of the squares and the Arab Spring in 2010-2012, and which continues to gain steam, but also the neoauthoritarian reaction to it, from Trump and Bolsonaro to Duterte, Orbán, and Salvini.5 While uprisings are driven overwhelmingly by youths and poor workers angered by neoextractivist price gouging and opportunity hoarding by so-called “corrupt” elites, leaving many in Gen Z with no future path but to depart for work abroad, today’s neopopulist strongmen draw support from a downwardly-mobile petty bourgeoisie anxious about contracting economic growth and diminishing returns on long-held social privileges.

As the crisis of growth worsens, the strategic cycle of force relations necessary to prop up the market gradually separates itself, resulting in a disappearance of mediations for all parties, above and below: trade deficits are solved by intimidation, war, and plunder from above, while from below, even modest social-economic tensions now pass directly into mass unrest and revolts. These twin dynamics proceed in lockstep with each other. Not a month goes by where the far right doesn’t make electoral gains or proclaim neogenocidal policies out loud in a new country; meanwhile, each week, a new wave of mass unrest breaks out that incinerates police stations and parliament buildings, blocks roads and freeways, occupies plazas, loots palaces and storefronts, chases rulers from their residences, and refuses to disperse until it is either defeated by force or succeeds in deposing a head of state.

IV. The reemergence of the strategic plane is not a rupture with liberal institutions, but is proceeding through its institutions.

Two confusions must be avoided, at this point. First, that the present moment constitutes a total dismissal of the liberal-democratic legal and political orders that preceded it. Many liberals have sought to present the Trump administration’s domestic policies as a subversion of democratic norms and policies, which must therefore be defended. In fact, the reverse is the case. What sets the “new fascisms” apart from those of the past is not their emergence within the framework of liberal democracy, which was already true of their 20th century predecessors. Rather (as comrades in Chile recently argued), the difference lies in how contemporary liberal states “were able to perfect fascist policies and allow them to be deployed even within a democratic framework, to the point that they have been able to build an industry around crime and insecurity as justifications for the establishment of these policies.”6 Any genuine recognition of this fact would require that critiques of the fascistic tendencies of the Trump administration be accompanied by a thoroughgoing critique of democracy; instead, the progressive left persists in its wrongheaded belief in the total opposition between democracy and fascism. At the same time, however, the reliance of latent fascisms upon preexisting democratic legal frameworks must not lead us to believe that a return to liberal democracy is still possible today. Supporters of Zohran Mandami who believe they’ve turned the car around are merely committing to the bit. In fact, fascism’s transitional dependency upon liberal democracy serves merely as the necessary prerequisite for thinking through the requirements of what comes next.

V. The sole certainty shared by all concerns the need for a leap.

That we live in an interregnum between a dying order and another not yet stabilized means that the sole certainty shared by all contending parties is that we are in the midst of a rupture, that the contradictions of our present cannot be solved by means of the instruments and procedures of the institutions that brought us here, even if they persist in some fashion today.

What is needed is a “leap out of the situation.”7 The need for this leap is felt everywhere, sometimes inchoately, at other times consciously. It is this leap that is already being prepared and initiated chaotically all around us, and which accounts for the startling audacity erupting from every corner of society, from the gamer attentats to the brutish cynicism of the Israeli genocide in Gaza, to the Nepalese youths and underclass who, in revenge for the 21 demonstrators slain by their government on September 8, in a single day set ablaze their Supreme Court, parliament, the prime minister’s house, the president’s house, as well as dozens of police stations, supermarkets, and a media headquarters, toppling a government “in less than 35 hours.”8 It is this leap, whose foreshocks can already be felt everywhere, that must be thought through, organized, and strategically carried forward into an irreversible break with the rule of the economy.

VI. Contemporary revolts have, at best, produced a consciousness of capital, but not of its overcoming.

In a condition in which constitutional reforms can only be won through revolt, the problem of their relation to revolution must be rethought.

Revolts are everywhere, yet with the possible exception of the civil war in Myanmar (still undetermined), the vast majority — shocked by the ease of their victories over the forces of order — wind up demanding little more than a negotiated return to the status quo. This pattern was notably present already in the 2022 uprising in Sri Lanka:

Struggles are often defeated not by the state but by the shock of their own victory. Once they have gathered momentum, movements tend to achieve their goals far quicker than anyone would have expected. The fall of the Rajapaksa regime happened so fast that no one seriously considered what would need to follow it. The window it had opened soon closed. The suffocating air of normalcy filled the room.9

A key limitation of contemporary revolts lies in the frame of struggle itself, which tends to interpret shortfalls of subsistence as the symptom of corruption, austerity, and cronyism.10 This framing, which does not challenge capitalism itself but only its current (mis)management, inevitably terminates in a reshuffling of the deck:

[C]ritiques of corruption misrepresent the agency the state actually has within economic and social crises, since it presumes that the state could find a way out of the present crisis, that it could choose to avoid implementing austerity, if it only wanted to. [...] After the fall of the regime, people are confronted with the fact that the structural logic of capitalist society remains in place. Governments ushered in by the revolution often find themselves implementing austerity measures similar to the ones that had initially triggered the protests.11

On the one hand, these failings might themselves be expected to contribute to the emergence of a more systemic critique of capitalism, a development of “class consciousness,” as the “essential unity of interests of the ruling class” become clear to anyone paying attention. However, as Prasad observes,

…it might be [more] accurate to think of this as developing a consciousness of capital. For the uprising to have gone further, it would have had to confront the uncertainty of how the country would eat and live while its relationship to the global market was interrupted. After all, it is only through and within the relations of capitalist society that proletarians are able to reproduce themselves at all.

In other words, if a revolt fails to confront the problem of a revolutionary rupture while order is suspended, the lesson internalized risks being that of the iron law of the economy: participants become conscious of capital as a current constraint on life, but unable to imagine its overcoming.12

VII. Revolts have generated alternative forms of self-organization and autonomy through which a revolutionary break could be organized, yet without understanding them as such.

In the 1950s, the German philosopher of technology Günther Anders described what he called a “Promethean gap” emerging in industrial societies, inverting the classical relation between imagination and action. Whereas utopianism was based on the idea that our imagination was larger than what currently existed, projecting itself beyond actuality, Anders argues that the opposite is the case in our day: with the invention of the nuclear bomb, a Promethean gap emerged wherein factual acts now exceed their agents’ own capacity to imagine, think, and feel them. We are no longer able to comprehend, let alone take responsibility, for what we are already doing.13 We have become “inverted utopians,” unable to contemplate the scale or repercussions of our own practices. We are smaller than our own deeds, which now conceal something unfathomable within them. Imagination not only fails to reach beyond the present, but even falls short of actuality.14

An analogous phenomenon can occur in political struggles. Even when pursuing reformist ends, participants sometimes accomplish breakthroughs whose true radicality remains underappreciated at the time, especially when it cannot be integrated into the inherited concepts and categories adopted by the struggle. Insurgents are therefore unable to work out the full implications of what they are already doing; nor will they necessarily notice when future cycles of struggles take up their impulses and push them in a new direction. It is in this gap between practice and reflection, between means and ends, between the impulses of one cycle and those that follow that theory can play an assistive role, by drawing out the excess concealed within the folds of history, its Entwicklungsfähigkeit.15

The Gilets Jaunes movement was exemplary in this respect. Among its many creative features, two advances stand out. Firstly, while its catalyzing factors were eminently familiar social pressures such as the rising cost of living, diminishing social mobility, cuts to public services, etc., the organization of the revolt circumvented traditional categories of political identification and social identity in favor of a simple, replicable gesture of self-inclusion: to join, one need simply put on the vest and go do something. In doing so, the movement leaped right over the Trotskyist problem of a “convergence” between social movements forged in separation (students, workers, migrants, etc.). While every political struggle requires some method of formalization to demarcate belonging, the usage of a quotidian object such as a high-visibility vest or an umbrella to accomplish this effectively ensured that the fighting force would be defined first of all by its contagious initiatives that it circulated, and not by reference to any particular social group authorized to represent it. This allowed the Yellow Vests to successfully sidestep a central mechanism of governance, which leverages our attachment to our own social identities to contain antagonisms within the confines of institutional channels (university policies, workplace disputes, etc.). From Hong Kong’s frontliners to the “youthquakes” of today, gathered under the impersonal sigil of a manga pirate flag16, revolts now erupt as viral contagions or memes-with-force, inviting more open-ended experimentation and reducing their potential for recuperation. However, unable to recognize the force of their own innovation, the Gilets Jaunes fell back upon the imaginary of the French revolution and its floating signifier, “le peuple” [the People], leading many to confuse their innovation with a resurgent right-wing populism. Over the inappropriable immanence of the meme, they reinscribed the symbolic transcendence of myth.17

Secondly, while many revolts find themselves magnetized by the symbols of bourgeois power, concentrating their forces at the feet of ruling class institutions such as courthouses, parliaments, and police stations, the Gilets Jaunes established the bases from which they organized their struggle, strategized, and shared their life in a tight proximity to their everyday lives. As was observed at the time,

This proximity to everyday life is the key to the revolutionary potential of the movement: the closer the blockades are to the home of the participants, the more likely these places can become personal and important in a million other ways. And the fact that it is a roundabout that is occupied rather than a forest or a valley strips the prefigurative or utopian content from these movements. [...] [T]o occupy the roundabout near where one lives ensures that the collective confidence, tactical intelligence, and shared political sensibility the Yellow Vests cultivate from one day to the next traverses and contaminates the networks, ties, friendships and bonds of social life in these same areas.18

Feelings that remain utopian in an occupied downtown plaza or in a space like the ZAD (where most participants don’t themselves live), once shifted to the roundabout, are now able to bleed into everyday life rather than remaining apart from it. And when such bases come under attack by repressive forces, the resources of private life are able to restock and reconstruct it, as we saw in Rouen, where the makeshift cabins built on the roundabout were destroyed and rebuilt half a dozen times.19

The innovation was not merely a function of proximity to everyday life; for in this case, occupying the village centers across the countryside could also have sufficed. By positioning their base of operations at the threshold between the economy and quotidian life — at the precise point where trucks carrying goods along freeways needed to enter the city — the roundabouts also positioned themselves to function as filtration blockades, conferring logistical leverage upon the insurgents. By blocking circulation not at the point of greatest importance to capital but at the point where capital enters the space of everyday life, they politicized the membrane between life and money on terms amenable to them, not at the site dictated by the symbols of bourgeois power, as Occupy Wall Street had done. In reality, “the true strategic horizon of hinterland blockades is not to suspend the flows of the economy completely, but to produce inhabited territorial bases that restore it to the map of everyday life, at a level at which it can be seized upon and decided.”20 This combination of a logistical intelligence positioned at the threshold of everyday life, yet federated nationally through regional and national spokescouncils and assemblies21, offered an original and potent paradigm for insurrectional self-organization.

Yet here again, it is unclear whether the Gilets Jaunes ever fully appreciated their creative act for what it was. Rather than recognizing that they were in the process of reimaging the very forms and practices by which the slogan, “all power to the communes,” could be adapted to our times, a narrow focus on securing the resignation of Macron led many to embrace merely a different form of parliamentary proceduralism, namely the so-called Citizens Referendum Initiative (RIC).22

For Jerôme Baschet, by contrast, the construction of these “liberated spaces” — when carried through to its conclusion — could instead have served as the base premise for a broader assault on the economy, one that not only deepened the “links between existing liberated spaces,” but combined

…the multiplication of liberated spaces with generalizing blockades. To the extent that the liberated spaces are capable of deploying their own material resources and technical capacities, they can serve as decisive nodes on the basis of which it becomes possible to amplify the blockade dynamics at key moments, in various forms. The more liberated space we have, the more we should be able to extend our capacity for blockades. Conversely, the more widespread the blockades become, the more they promote the emergence of new liberated spaces.23

Of course, the danger would be to think that what is needed is simply a repetition of the Gilets Jaunes moment. This mistake, which seemed to permeate the bizarre speculative bubble this summer around the September 10th “Block everything” initiative in France, stems from a tendency to disconnect the problem of tactics and practices from the event-like rupture of their emergence.24 Those who would force history to repeat itself only guarantee farce.

VIII. In its practical impulses, the struggle against ICE points toward an overcoming of the separations that hampered the 2020 George Floyd uprising.

The offensive capacity of the 2020 George Floyd uprising was hampered by a separation between its placemaking impulse and its logistical intelligence. The occupations that frontally besieged the halls of power (“political riot”) were never able to meaningfully combine forces with the looting caravans that swarmed strip malls and shopping districts in attack-and-withdraw maneuvers (“storefront riot”).25 As a result, logistical/infrastructural consciousness tended to remain relatively depoliticized, merely a collection of techniques, while the political consciousness remained glued to evacuated edifices with largely symbolic value.26 With the construction of defense hubs, or “centros,” combined with other practices of autonomous tracking, stalking, and disruption, the current struggle against ICE has initiated a repoliticization of infrastructural intelligence, along with an inversion of its “cynegetic” orientation (from prey to predator). This fact, combined with the notable tendency to resituate the political back in spaces of everyday life, all point toward an overcoming of the limits of 2020 — regardless of whether its agents have thematized it as such.

Following the invasion of US cities like DC, Chicago, and Portland by federal forces, the symbolic magnetism initially held by sites of power such as the ICE Detention Center in Broadview, IL has given way to a diffuse ethos of neighborhood self-organization, even traversing unlikely class and race barriers. The center of gravity has been displaced away from the meat grinder of siege warfare around enemy fortresses and back toward the spaces of everyday life, a fact to be welcomed. Residents flood their blocks upon hearing the mockingbird call of horns and whistles, caravans of private vehicles stalk and disrupt ICE agents up and down local boulevards, while neighbors rally around schools, workplaces, and street vendors. Neighborhood defense councils have mushroomed up across Chicago, as well as elsewhere in the country, with activists setting up defense hubs in Home Depot parking lots and other spaces frequented by day-laborers. According to one recent how-to guide, these hubs serve as spaces of encounter that extend beyond the affinities of political subculture or work life, “offering outraged people place-based relationships that give their anger direction.”27

As the nexus of everyday life and social reproduction becomes increasingly politicized, the logistical intelligence usually reserved for storefront looting and smash and grabs begins to generalize, de-specialize, and become accessible to anyone willing to hop on a local signal thread and begin patrolling. Practices of collective surveillance from below, paired with a concrete set of tasks — prevent arrests, ensure safe passage, harass and evict hostiles — are slowly accomplishing what two decades of social movements have consistently failed to do: to reintroduce collective participation in metropolitan space on a partisan, non-economic basis.

Political strategies are only as coherent as the truths upon which they rest. This recognition led participants in the 2019 Hong Kong uprising to place a premium on information-vetting and fact-checking. These practices have found new expression in today’s anti-ICE struggles, which combine infrastructural knowledge-sharing with a collective ethos of presence to one’s situation. In cities across the US, a new form of political empiricism combs everyday life for signs of the enemy. In order to intervene and prevent kidnappings, rapid response networks depend upon surveillance intel sourced from activists patrolling areas by car or on foot, or else from reports posted on social media. This intel is then filtered through large Signal threads that compare vehicle descriptions and license plates, pull VIN numbers, and swap location details in real time. While usage of the SALUTE protocol28 ensures information is complete and actionable, there is more at stake in these practices than merely a circulation of factual information. Alongside the production of this logistical intelligence a new political sensibility is being forged. The atomized individual experience of the city gives way to a power of collective attention, expressed both through a continuous tracking and profiling of the enemy as well as a sensitivity to the rhythms, flows, and qualitative relations that populate the places we inhabit. As the same how-to guide observes, defense hubs “will succeed or fail based on whether you are attentive to the needs of the surrounding area.”29 Through this apprenticeship to signs, the anti-ICE struggle is assisting in birthing a world in common.

The threat that this logistically-minded politicization of everyday life represents to the legitimacy of governing forces is considerable. It is no doubt for this reason that the Trump administration has attempted to preempt resistance to their own offensive by conferring upon it a pre-digested identity and a narrative. Rather than recognizing the struggle for what it is, namely, a memetic circulation of diffuse practices of subversion accessible to all irrespective of political ideologies or social identities, ruling forces project the myth of a hierarchical organization (“Antifa”) financed by liberal elites and organized militarily into “cells” that take orders from centralized authorities. The aim of this cartoonish and transparently false narrative is not to convince anyone of its literal truth (of which there is none), but to conceal the sensible evidence that grows more forceful every day: the citizen/noncitizen binary is an intolerable tool of violent apartheid.

What other potentialities might this new wave of contestation harbor within it, still unseen by its own participants? What could a diffuse network of neighborhood councils powered by collective logistical intelligence and a highly mobile capacity for disruption and intervention accomplish if it scaled up even three steps further? In order to effectively prevent arrests and protect neighbors, more ambitious forms of logistical blockades could be needed. What would it take to begin staging coordinated actions across entire cities, or establishing filter blockades to secure community-control over zones or neighborhoods? What other ambitions could such techniques of popular power be leveraged to accomplish, if and when ICE pulls out of these cities?

IX. The end of mediation could spell the end of the Left. A new revolutionary underground could take shape in its wake.

As contending forces compete to shape the direction that the leap beyond liberal democracy will take, mediations will continue to dissolve. As a principal vector of “soft power,” the left’s role in containing rebellious energy through the promise of state recognition and reform might cease to function. As the right continues its frontal attack on the bases of leftist culture, firing professors and criminalizing activists and students, while defunding LGBTQ and migrant rights NGOs, an opportunity emerges to reinvent the political underground anew. Here the case of Sudan might be instructive. As Prasad writes,

After an uprising in 2013, a proliferation of resistance committees emerged that set themselves the task of preparing for the next wave of struggles. Specifically, this meant: maintaining neighborhood social centers; building the infrastructure and stockpiling materials that they thought would be necessary; developing city-wide and national networks of comrades and sympathizers; and testing the capacity of these networks through coordinated campaigns. When the revolution did come, in late 2018, these groups were able to act as vectors of intensification. The resistance committees were also able to sustain the revolution into its next phase, after President Al-Bashir was forced to step down.30

The exact tasks that a post-left underground must undertake today remain to be clarified. If public reaction to Luigi Mangione has proven anything, it is that it needn’t draw its political coordinates from the classical left/right culture war. It is possible that a broad, combative, and daring movement capable of mining recent history for its gaps, resurrecting its insights tactfully, and pursuing their conclusions ruthlessly can resonate well beyond the confines of the cultural silos of the ultraleft milieu, enjoying broad resonance in a time of profound uncertainty.

Over a century ago, Kropotkin proposed the following corrective:

“Still,” our friends often warn us, “take care you do not go too far! Humanity cannot be changed in a day, so do not be in too great a hurry with your schemes of expropriation and anarchy, or you will be in danger of achieving no permanent result.” Now, what we fear with regard to expropriation is exactly the contrary. We are afraid of not going far enough, of carrying out expropriation on too small a scale to be lasting. We would not have the revolutionary impulse arrested in mid-career, to exhaust itself in half measures, which would content no one, and while producing a tremendous confusion in society, and stopping its customary activities, would have no vital power — would merely spread general discontent and inevitably prepare the way for the triumph of reaction.31

If and when the tide turns back in their favor, if police stations are once again burning and politicians are hiding in bunkers or fleeing in helicopters, insurgents must not be caught off guard. They must not allow the commune to be replaced by the virtual parliament of Discord servers, but must use the opportunity to advance widespread, in-person experiments in communist sharing that draw in as many participants as possible.

While nothing currently imaginable is adequate, history contains furrows that might still surprise us.

October 2025

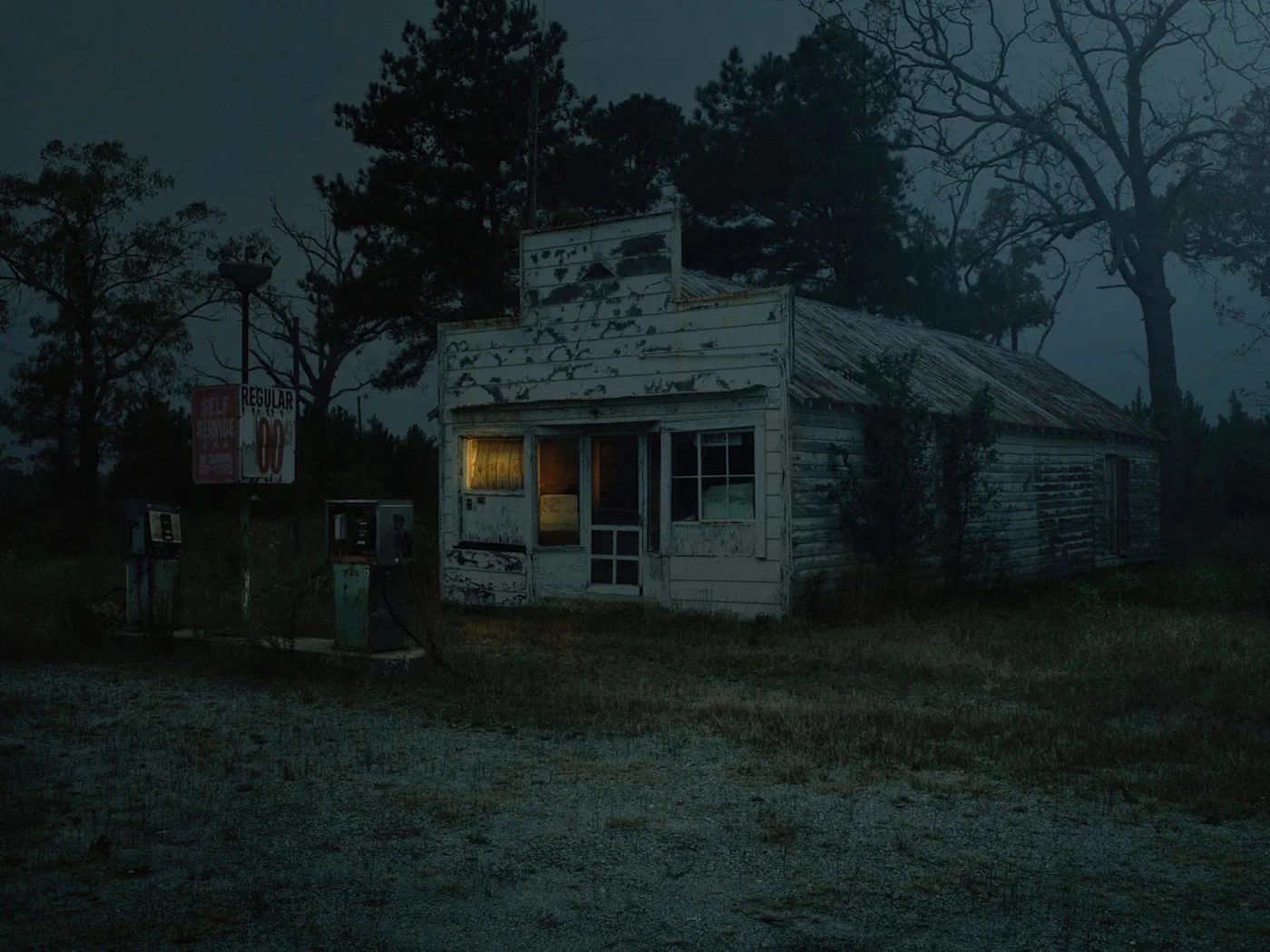

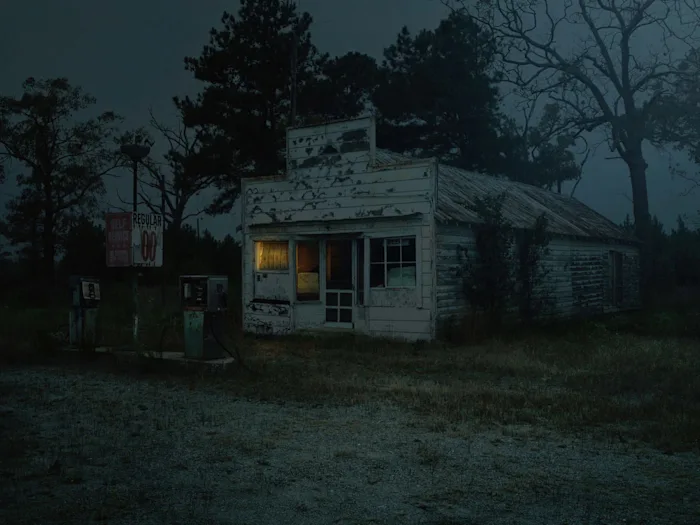

Images: Christopher Thomas

Notes

1. As the meme of the One Piece flag circulates, it takes on local accoutrements. In Madagascar, for example, the straw hat is replaced by the satroka bucket hat traditionally worn by the Betsileo ethnic group. Still, it is significant that the national identity rides like an accessory atop the contagious symbol or sigil, and not the reverse. See Monica Mark, ‘‘Gen Z’ protesters in Madagascar call for general strike,” Financial Times, October 9, 2025 (online).↰

2. Blaumachen, “The Transitional Phase of the Crisis: the Era of Riots,” 2011 (online). ↰

3. Maurizio Lazzarato, “The United States and ‘Fascistic Capitalism,’” translated by Eric Aldieri, Ill Will, October 7, 2025 (online).↰

4. Interview cited in Vasudha Mukherjee, “Trump turns ally investments into $10 trillion US 'sovereign wealth fund,’” Business Standard, Aug 14, 2025 (online).↰

5. That the era of revolts arrived on the scene first, and was only later complemented by a fascizing effort to reimpose a US-centric order domestically and internationally, should not confuse us. The Invisible Committee’s balance sheet of the 2008-2013 cycle concluded with these words: “Nothing guarantees that the fascist option won’t be preferred to revolution.” The Invisible Committee, To Our Friends, translated by Robert Hurley, Semiotexte, 2014 (online here).↰

6. Nueva Icaria, “New Fascisms and the Reconfiguration of the Global Counterrevolution, Ill Will, August 11, 2025 (online).↰

7. Lazzarato, “‘Fascistic Capitalism.’”↰

8. Pranaya Rana, “The Week after Revolution,” Kalam Weekly (Substack), September 19, 2025 (online). ↰

9. S. Prasad, “Paper Planes,” August 31, 2022 (online). ↰

10. Phil Neel distinguishes between struggles over the economic/ecological “terms of subsistence” and those over the authoritarian “imposition of these terms” (“Theory of the Party,” Ill Will, September 6, 2025; online). The global trend of late has been for mass, nonviolent social movements demanding reformed terms of subsistence to be catapulted into militancy when the forces of order overreact and open fire, thereby shifting the frame of the struggle from the first category to the second, from austerity to authority. The United States is an exception to this pattern: while the austerity measures supply backdrop pressures, in recent decades struggles over economic issues almost never escalate into mass combative unrest, which is only ever catalyzed by authoritarian means of enforcement. While revolt is unlikely to ever break out here over food stamp cuts, housing precarity, or denial of healthcare per se, activist networks forged by means of subsistence struggles do, nevertheless, occasionally contribute to deepening anti-authoritarian mass unrest, as occurred when the Los Angeles tenants’ union infrastructure was leveraged to establish anti-ICE defense hubs in the wake of the June 2025 riots. ↰

11. Prasad, “Paper Planes.” ↰

12. In this case, the shortfall of the imagination is a function of practical experiments that were not undertaken when they should have been. Thesis VII explores the inverse scenario, in which experiments were undertaken whose potency went overlooked. ↰

13. Günther Anders, “Theses for the Atomic Age,” The Massachusetts Review, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Spring, 1962), 496.↰

14. For example, to refer to nuclear bombs as “weapons” and debate their tactical usage is to liken them to a tool, a means to some end; yet the usage of such bombs threatens to destroy the very world in which any and all such “ends” could be achieved. Their usage therefore cancels out any means-ends relation, making all tactical considerations impertinent. Yet this instrumental attitude remains the only way in which the imagination is able to think about them, in spite of its being a category error. See Gunther Anders, “Commandments in the Atomic Age,” in Burning Conscience, Monthly Review Press, 1962, 15-17. ↰

15. Gilbert Simondon maintained that the “artificiality” of our relation to technical objects could be corrected only provided that we learn to conceive their evolution genetically, i.e., by decoupling it from the human purposes projected over them and instead grasping the development of their elements, ensembles, and associated milieus on its own terms. In an analogous fashion, when we study the evolution, mutation, and circulation of practical impulses and gestures across diverse sequences of struggle, it can help to methodologically suspend reference to the ends that participants in these struggles set for themselves and try to consider their evolution from one cycle to the next on its own terms. Some have expressed concern that this focus on the circulation and evolution of practices risks succumbing to what Kiersten Solt calls the “nihilism of technique.” In fact, it seems to me that pro-revolutionaries still do not think technically enough. Too many continue to reify an abstract and ahistorical concept of political action in which methods of struggle flowed immediately from the ends pursued or could simply be adopted voluntaristically by pure fiat. In practice, actuality precedes possibility: all struggles base their experience of what is politically possible on a reservoir of impulses previously in circulation, innovating within the limits set therein. It is this extant menu or repertoire — what we could call the tactical phylum — that sets out the boundaries of what is imaginable. And, far from racing ahead of it, our imagination often falls short of it. Consequently, instead of projecting ethical and political values ahead of reality and treating practice as merely a means to realize them, our analysis of practice can be used to push open our imagination, thereby rendering actuality possible again. This requires tracing the evolution of practical impulses across sequences of struggle in search of rifts, breakthroughs, and moments where limits were overcome. ↰

16. By adopting the “Jolly Roger” as its global banner, 2025’s wave of uprisings converted the term “Gen Z” from a banal demographic designation into the symbol of a shared dispossession. Through its viral circulation from Indonesia and Nepal to Madagascar, Morocco, and Peru, the “Gen Z” pirate flag today attests to a familiar tension between the state and capital: with all the good local jobs hoarded by nepo babies, you need to travel abroad to make money; yet as the neoliberal order implodes, states are closing their borders. The result is a contradictory experience: workers are uprooted yet hemmed-in, with their only remaining access to the globe being online. The virtual community of pirate freedom is precisely the negative reflection of this landlocked economic condition. Of course, this condition is by no means limited to young people. The emphasis on “youth” appears to have more to do with a paradoxically negative virtue: to not have dirty hands. To be young means to be not yet in power, not yet running a racket, not yet implicated in networks of local and global power-sharing, not yet corrupt. It is this negativity — and not the positive predicate of one’s age — that has allowed a fighting force to coalesce around the marker “Gen Z.” ↰

17. For an opposed reading that affirms the Yellow Vests’ usage of myth, see “Epistemology of the Heart,” in Liaisons Vol. 2: Horizons, PM Press, 2022 (online). As the authors themselves concede, however: “The problem is that while the fulfillment of myth contributes to the strength of the struggle, the tradition of the defeated must stay defeated in order to remain a tradition” (375). Here as always, the affirmation of myth proves to be inseparable from a cult of exemplary death, a religio mortis. Communism, in my view, must be a wager on earthly life, not eternity. ↰

18. Adrian Wohllbeben and Paul Torino, “Memes with Force. Lessons from the Yellow Vests,” Mute, February 26, 2019 (online).↰

19. Adrian Wohlleben, “The Counterrevolution is Failing,” Commune, Feb 16, 2019 (online). ↰

20. Adrian Wohlleben, “Memes without End,” Ill Will, May 17, 2021 (online). Reprinted in The George Floyd Uprising, ed. Vortex Collective, PM Press, 2023, 224-47. ↰

21. Anonymous, “Learning to Build Together: the Yellow Vests,” Ill Will, May 9, 2019 (online). ↰

22. “Référendum d'initiative Citoyenne” (RIC) refers to a proposed “constitutional amendment in France to permit consultation of the citizenry by referendum concerning the proposition or abrogation of laws, the revocation of politicians' mandates, and constitutional amendment.” Wikipedia (online). ↰

23. Jérôme Baschet and ACTA, “History Is No Longer on Our Side: An Interview with Jérôme Baschet,” Mute, January 23, 2020 (online). ↰

24. Temps Critiques, “On the 10th of September,” Ill Will, September 10, 2025 (online). ↰

25. This argument is explored further in Wohlleben, “Memes without End.” ↰

26. The lesson to be drawn from sequences such as Kazakhstan in 2022, or Nepal this summer, is not that the halls of power should be ignored or left in peace, but that there is nothing to be done with them except to dispassionately raze them to the ground. From this vantage point, even the pool party in Sri Lanka lasted a little too long, and detracted from festivities that ought to have happened in the streets, the neighborhoods, and service stations throughout the country. While Nepalese protesters reduced physical symbols of bourgeois power to ash, they have not yet built bases of independent popular power in proximity to inhabited zones, instead retreating to virtual forums on Discord channels where they plotted to have their chosen politicians given positions of power. Despite the ferocity of their assault, the parliamentarian concept of politics emerged unscathed. ↰

27. Lake Effect Collective, “Defend our Neighbors, Defend Ourselves! Community Self-Defense from Los Angeles to Chicago,” 4 (online). Although the text wavers between a “proactive” posture of autonomous intervention (4) and an ally politics limited to “support and facilitation” of what so-called “locals” do (positioning the authors as extraterrestrials) (5), it offers a strong practical toolkit for individuals and collectives looking to get involved in the present moment. ↰

28. SALUTE is a mnemonic device that stands for: size/strength (S), actions/activity (A), location & direction (L), uniform/clothes (U), time and date of observation (T), equipment/weapons (E). This framework is used to ensure that detailed and complete information is provided when reporting an observation. ↰

29. Lake Effect Collective, “Community Self-Defense,” 9. ↰

30. Prasad, “Paper Planes.” With the difference that, whereas Sudan’s neo-councilist movement was eventually defeated by inability to defend itself, an American uprising will instead need to exert its full inventiveness simply to forestall the shooting war that lingers beneath the surface, in order that experiments in collective autonomy can flourish and fortify themselves in the meantime.↰

31. Peter Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread and Other Writings, Cambridge University Press, 48. ↰